Ethical Considerations for Machine Learning Research Using Free-Text Electronic Medical Records: Challenges, Evidence, and Best Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.5. Results

3. Ethical Dimensions of Machine Learning in Health Research

3.1. How Can Privacy and Confidentiality Be Preserved in Free-Text EMR Data?

- Ethical oversight, requiring institutional review boards to assess text-specific risks and mitigation [24].

3.2. How Should Bias and Fairness Be Managed in Text-Based ML Models?

3.3. What Are the Obligations Around Consent, Autonomy, and Transparency?

3.4. How Can Validity, Interpretability, and Accountability Be Maintained in Text-Based ML Research?

3.5. How Should Governance, Stewardship, and Global Ethical Harmonization Be Structured?

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategy

- Web of Science [1311]

- PubMed [1922]

- IEEE [1395]

- EMBASE [197]

- CINAHL [46]

References

- Wu, G.; Yang, F. Navigating the Transformative Impact of Artificial Intelligence in Health Services Research. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Eastwood, C.; Zeng, Y.; Quan, H.; Long, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Ghali, W.A.; Bakal, J.; Boussat, B.; Flemons, W. Developing EMR-based algorithms to Identify hospital adverse events for health system performance evaluation and improvement: Study protocol. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Soo, A.; Ronksley, P.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Wu, Q.; Quan, H.; Stelfox, H.T. A multicenter cohort study of falls among patients admitted to the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 50, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, E.; Rana, R.; Higgins, N.; Soar, J.; Barua, P.D.; Pisani, A.R.; Turner, K. Natural language processing in electronic health records in relation to healthcare decision-making: A systematic review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 155, 106649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosowan, L.; Singer, A.; Zulkernine, F.; Zafari, H.; Nesca, M.; Muthumuni, D. Pan-Canadian Electronic Medical Record Diagnostic and Unstructured Text Data for Capturing PTSD: Retrospective Observational Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e41312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Cheligeer, C.; Southern, D.A.; Martin, E.A.; Xu, Y.; Leal, J.; Ellison, J.; Bush, K.; Williamson, T.; Quan, H. Development of machine learning models for the detection of surgical site infections following total hip and knee arthroplasty: A multicenter cohort study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2023, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Khair, S.; Yang, F.; Cheligeer, C.; Southern, D.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Quan, H.; Williamson, T. Performance of machine learning algorithms for surgical site infection case detection and prediction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 84, 104956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheligeer, K.; Wu, G.; Laws, A.; Quan, M.L.; Li, A.; Brisson, A.-M.; Xie, J.; Xu, Y. Validation of large language models for detecting pathologic complete response in breast cancer using population-based pathology reports. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Cheligeer, C.; Brisson, A.-M.; Quan, M.L.; Cheung, W.Y.; Brenner, D.; Lupichuk, S.; Teman, C.; Basmadjian, R.B.; Popwich, B. A new method of identifying pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer patients using a population-based electronic medical record system. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 2095–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, K.; Klein-Geltink, J.; Mitiku, T.F.; Mihai, C.; Martin, J. De-identification of primary care electronic medical records free-text data in Ontario, Canada. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2010, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.H.; Ford, E.M.; Lea, N.; Griffiths, L.J.; Hassan, L.; Heys, S.; Squires, E.; Nenadic, G. Toward the development of data governance standards for using clinical free-text data in health research: Position paper. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e16760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecki, J.; Walkiewicz-Żarek, E.; Figas-Skrzypulec, J.; Kordecka, A.; Dranseika, V. Ethical issues in biomedical research using electronic health records: A systematic review. Med. Health Care Philos. 2021, 24, 633–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Eastwood, C.; Sapiro, N.; Cheligeer, C.; Southern, D.A.; Quan, H.; Xu, Y. Achieving high inter-rater reliability in establishing data labels: A retrospective chart review study. BMJ Open Qual. 2024, 13, e002722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, T.A.; Lamé, G.; Zehou, O.; Skayem, C.; Monnet, P.; El Khemiri, M.; Boudjemil, S.; Hirsch, G.; Wolkenstein, P.; Jankovic, M. A process modelling approach to assess the impact of teledermatology deployment onto the skin tumor care pathway. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 146, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Medical Informatics Association. IMIA code of ethics for health information professionals. Retrieved April. 2002, 14, 2004. Available online: https://imia-medinfo.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/IMIA-Code-of-Ethics-2016.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Neamatullah, I.; Douglass, M.M.; Lehman, L.-W.H.; Reisner, A.; Villarroel, M.; Long, W.J.; Szolovits, P.; Moody, G.B.; Mark, R.G.; Clifford, G.D. Automated de-identification of free-text medical records. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2008, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meystre, S.M.; Savova, G.K.; Kipper-Schuler, K.C.; Hurdle, J.F. Extracting information from textual documents in the electronic health record: A review of recent research. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2008, 17, 128–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y. Digital pathways connecting social and biological factors to health outcomes and equity. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, P.-H.C.; Krause, J.; Peng, L. How to read articles that use machine learning: Users’ guides to the medical literature. JAMA 2019, 322, 1806–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abadi, M.; Chu, A.; Goodfellow, I.; McMahan, H.B.; Mironov, I.; Talwar, K.; Zhang, L. Deep learning with differential privacy. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016; pp. 308–318. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Su, C.; Walker, P.; Bian, J.; Wang, F. Federated learning for healthcare informatics. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2021, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, Z.; Han, S. Deep leakage from gradients. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32, Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, E.; Carroll, J.A.; Smith, H.E.; Scott, D.; Cassell, J.A. Extracting information from the text of electronic medical records to improve case detection: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panch, T.; Szolovits, P.; Atun, R. Artificial intelligence, machine learning and health systems. J. Glob. Health 2018, 8, 020303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, A.; Keniston, A.; Madhuripan, N. Synthetic data trained open-source language models are feasible alternatives to proprietary models for radiology reporting. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Powers, B.; Vogeli, C.; Mullainathan, S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 2019, 366, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, A.; Hardt, M.; Howell, M.D.; Corrado, G.; Chin, M.H. Ensuring fairness in machine learning to advance health equity. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Recommendation of the Council on Health Data Governance; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Cai, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Fang, S.; Wang, G. Data processing and text mining technologies on electronic medical records: A review. J. Healthc. Eng. 2018, 2018, 4302425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzuner, Ö.; South, B.R.; Shen, S.; DuVall, S.L. 2010 i2b2/VA challenge on concepts, assertions, and relations in clinical text. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2011, 18, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dernoncourt, F.; Lee, J.Y.; Uzuner, O.; Szolovits, P. De-identification of patient notes with recurrent neural networks. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2017, 24, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TCPS 2: CORE-2022 (Course on Research Ethics). 2022. Available online: https://tcps2core.ca/welcome (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence for Health; WHO Guidance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Rivera, S.C.; Moher, D.; Calvert, M.J.; Denniston, A.K.; Chan, A.; Darzi, A.; Holmes, C.; Yau, C.; Ashrafian, H. Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: The CONSORT-AI extension. Sci. J. Newsl./Rev. Científicas Y Boletines 2024, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, E.A.; Campion, T.R. Design and implementation of an integrated data model to support clinical and translational research administration. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2022, 29, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelona, V.; Scharp, D.; Idnay, B.R.; Moen, H.; Cato, K.; Topaz, M. Identifying stigmatizing language in clinical documentation: A scoping review of emerging literature. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, T.; Yatskar, M.; Ordonez, V.; Chang, K.-W. Gender bias in coreference resolution: Evaluation and debiasing methods. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.06876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veinot, T.C.; Mitchell, H.; Ancker, J.S. Good intentions are not enough: How informatics interventions can worsen inequality. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Faes, L.; Kale, A.U.; Wagner, S.K.; Fu, D.J.; Bruynseels, A.; Mahendiran, T.; Moraes, G.; Shamdas, M.; Kern, C. A comparison of deep learning performance against health-care professionals in detecting diseases from medical imaging: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digit. Health 2019, 1, e271–e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Wu, S.; Zaldivar, A.; Barnes, P.; Vasserman, L.; Hutchinson, B.; Spitzer, E.; Raji, I.D.; Gebru, T. Model cards for model reporting. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Atlanta, GA, USA, 29–31 January 2019; pp. 220–229. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, R.-M.A.; Stettner, J.L.; York, L. Healthy spaces: Legal tools, innovations, and partnerships. J. Law Med. Ethics 2019, 47, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumyn, A.; Barton, A.; Dault, R.; Safa, N.; Cloutier, A.-M.; Ethier, J.-F. Meta-consent for the secondary use of health data within a learning health system: A qualitative study of the public’s perspective. BMC Med. Ethics 2021, 22, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, J.; Whitley, E.A.; Lund, D.; Morrison, M.; Teare, H.; Melham, K. Dynamic consent: A patient interface for twenty-first century research networks. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 23, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumyn, A.; Ménard, J.-F.; Barton, A.; Dault, R.; Lévesque, F.; Ethier, J.-F. Patients’ and members of the public’s wishes regarding transparency in the context of secondary use of health data: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e45002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayena, E.; Blasimme, A.; Cohen, I.G. Machine learning in medicine: Addressing ethical challenges. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrieri, D.; Howard, H.C.; Benjamin, C.; Clarke, A.J.; Dheensa, S.; Doheny, S.; Hawkins, N.; Halbersma-Konings, T.F.; Jackson, L.; Kayserili, H. Recontacting patients in clinical genetics services: Recommendations of the European Society of Human Genetics. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 27, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilala, M.H.; Chenchala, P.K.; Choppadandi, A.; Kaur, J.; Naguri, S.; Saoji, R.; Devaguptapu, B.; Tilala, M. Ethical considerations in the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning in health care: A comprehensive review. Cureus 2024, 16, e62443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hay, T.; Reps, J.M.; Yanover, C. Extensive benchmarking of a method that estimates external model performance from limited statistical characteristics. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerella, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Zhang, J.; Contreras, M.; Siegel, S.; Bumin, A.; Silva, B.; Sena, J.; Shickel, B.; Bihorac, A. Transformers and large language models in healthcare: A review. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 154, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI HLEG. High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence: Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce-Bobadilla, A.V.; Schmitt, V.; Maier, C.S.; Mensing, S.; Stodtmann, S. Practical guide to SHAP analysis: Explaining supervised machine learning model predictions in drug development. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, S.; Ploug, T. Co-reasoning and epistemic inequality in AI supported medical decision-making. Am. J. Bioeth. 2024, 24, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.; Dhiman, P.; Riley, R.D.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; Reitsma, J.B.; Van Smeden, M. TRIPOD+ AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 2024, 385, e078378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habli, I.; Lawton, T.; Porter, Z. Artificial intelligence in health care: Accountability and safety. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.Y.; Pierson, E.; Rose, S.; Joshi, S.; Ferryman, K.; Ghassemi, M. Ethical machine learning in healthcare. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2021, 4, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otles, E.; Oh, J.; Li, B.; Bochinski, M.; Joo, H.; Ortwine, J.; Shenoy, E.; Washer, L.; Young, V.B.; Rao, K. Mind the performance gap: Examining dataset shift during prospective validation. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference, Virtual, 6–7 August 2021; PMLR; pp. 506–534. [Google Scholar]

- Cabitza, F.; Campagner, A.; Soares, F.; de Guadiana-Romualdo, L.G.; Challa, F.; Sulejmani, A.; Seghezzi, M.; Carobene, A. The importance of being external. methodological insights for the external validation of machine learning models in medicine. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 208, 106288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, A.; Dunbar, S.; Gruber, F.; McInerney, S.; Falis, M.; Linksted, P.; Wilde, K.; Harrison, K.; Hamilton, A.; Cole, C. Privacy-Aware, Public-Aligned: Embedding Risk Detection and Public Values into Scalable Clinical Text De-Identification for Trusted Research Environments. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.02063. [Google Scholar]

- Panigutti, C.; Hamon, R.; Hupont, I.; Fernandez Llorca, D.; Fano Yela, D.; Junklewitz, H.; Scalzo, S.; Mazzini, G.; Sanchez, I.; Soler Garrido, J. The role of explainable AI in the context of the AI Act. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Chicago, IL, USA, 12–15 June 2023; pp. 1139–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Sokol, K.; Fackler, J.; Vogt, J.E. Artificial intelligence should genuinely support clinical reasoning and decision making to bridge the translational gap. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, R.; Dave, D.; Naik, H.; Singhal, S.; Omer, R.; Patel, P.; Qian, B.; Wen, Z.; Shah, T.; Morgan, G. Explainable AI (XAI): Core ideas, techniques, and solutions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosheh, G.O.; Thwaites, C.L.; Zhu, T. Synthesizing electronic health records for predictive models in low-middle-income countries (LMICs). Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J. Introducing the ethical-epistemic matrix: A principle-based tool for evaluating artificial intelligence in medicine. AI Ethics 2025, 5, 2829–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankwa-Mullan, I. Health equity and ethical considerations in using artificial intelligence in public health and medicine. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2024, 21, E64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radanliev, P. Privacy, ethics, transparency, and accountability in AI systems for wearable devices. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1431246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannidis, E.; Mikalef, P.; Conboy, K. Responsible artificial intelligence governance: A review and research framework. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2025, 34, 101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeschoten, L.; Voorvaart, R.; Van Den Goorbergh, R.; Kaandorp, C.; De Vos, M. Automatic de-identification of data download packages. Data Sci. 2021, 4, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.X.; Campion, T.R.; Nutheti, S.L.; Peng, Y.; Raj, A.; Zabih, R.; Cole, C.L. Diri: Adversarial patient reidentification with large language models for evaluating clinical text anonymization. AMIA Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2025, 2025, 355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Norgeot, B.; Muenzen, K.; Peterson, T.A.; Fan, X.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Schenk, G.; Rutenberg, E.; Oskotsky, B.; Sirota, M.; Yazdany, J. Protected Health Information filter (Philter): Accurately and securely de-identifying free-text clinical notes. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallifant, J.; Afshar, M.; Ameen, S.; Aphinyanaphongs, Y.; Chen, S.; Cacciamani, G.; Demner-Fushman, D.; Dligach, D.; Daneshjou, R.; Fernandes, C. The TRIPOD-LLM reporting guideline for studies using large language models. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, R.J.; Kearney, J.; Cortes, Y.; Arcia, A.; Appelbaum, P.; Fernández, R.L.; Luchsinger, J. Benefits and risks in secondary use of digitized clinical data: Views of community members living in a predominantly ethnic minority urban neighborhood. AJOB Empir. Bioeth. 2015, 6, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safran, C.; Bloomrosen, M.; Hammond, W.E.; Labkoff, S.; Markel-Fox, S.; Tang, P.C.; Detmer, D.E. Toward a national framework for the secondary use of health data: An American Medical Informatics Association White Paper. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2007, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacherjee, S.; Chavan, A.; Huang, S.; Deshpande, A.; Parameswaran, A. Principles of dataset versioning: Exploring the recreation/storage tradeoff. Proc. VLDB Endowment. 2015, 8, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foalem, P.L.; Silva, L.D.; Khomh, F.; Li, H.; Merlo, E. Logging requirement for continuous auditing of responsible machine learning-based applications. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2025, 30, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, B.; Hu, Y.; Sotudian, S.; Zad, Z.; Adams, W.G.; Assoumou, S.A.; Hsu, H.; Mishuris, R.G.; Paschalidis, I.C. Development and validation of predictive models for COVID-19 outcomes in a safety-net hospital population. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2022, 29, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt, B.D.; Floridi, L. The ethics of big data: Current and foreseeable issues in biomedical contexts. In The Ethics of Biomedical Big Data; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 445–480. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, D.; Mazumder, A.; Peppin, A.; Wolters, M.K.; Hagerty, A. Does “AI” stand for augmenting inequality in the era of COVID-19 healthcare? BMJ 2021, 372, n304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Hasan, A.; Kueper, J.; Tang, T.; Hayes, C.; Fine, B.; Balu, S.; Sendak, M. Establishing organizational AI governance in healthcare: A case study in Canada. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavianpour, S.; Sutherland, J.; Mansouri-Benssassi, E.; Coull, N.; Jefferson, E. Next-generation capabilities in trusted research environments: Interview study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e33720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maamari, A. Between Innovation and Oversight: A Cross-Regional Study of AI Risk Management Frameworks in the EU, US, UK, and China. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.05773. [Google Scholar]

- EU Artificial Intelligence Act. The Eu Artificial Intelligence Act. European Union. 2024. Available online: https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

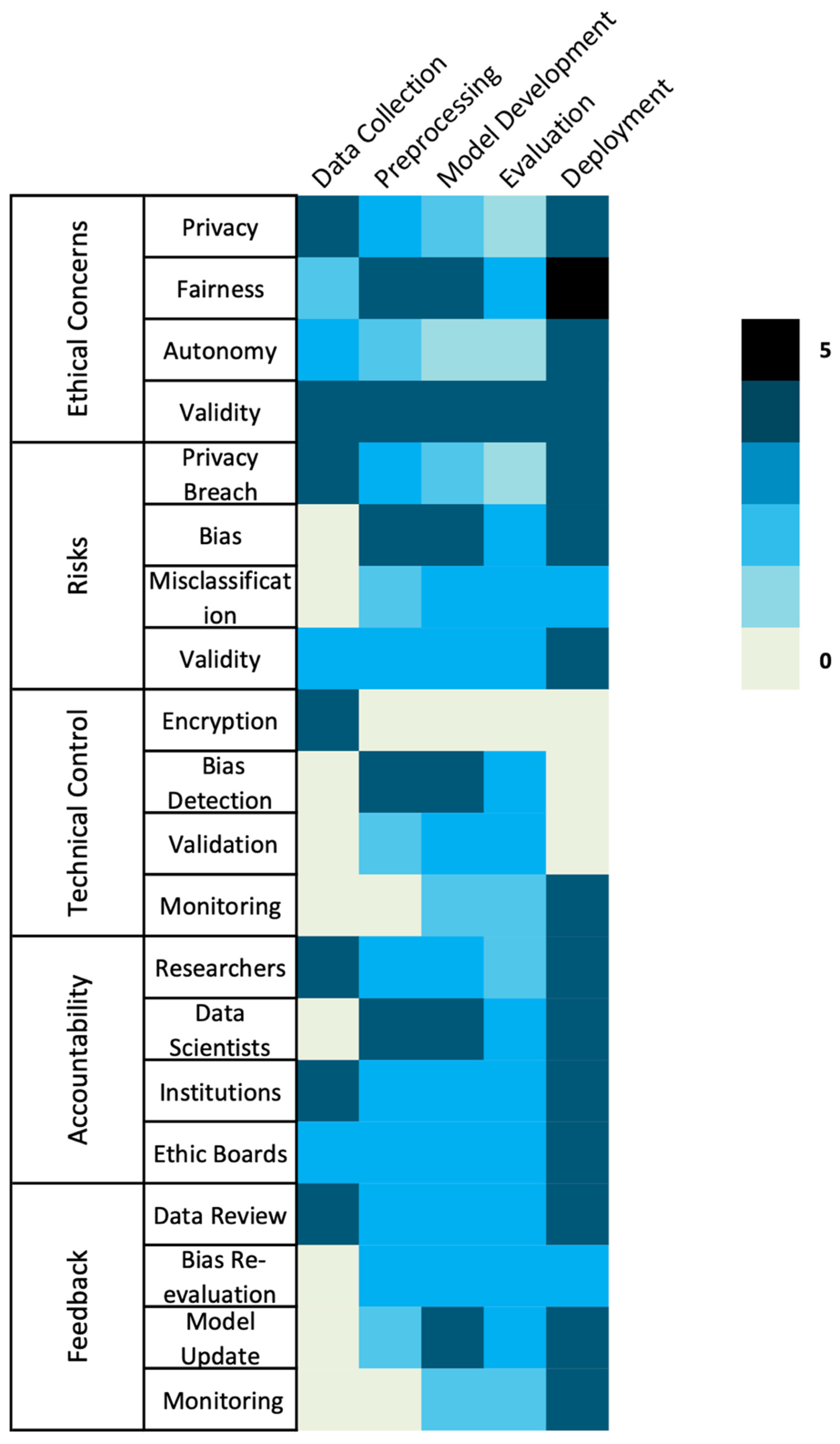

- Khan, U.S.; Khan, S.U.R. Ethics by Design: A Lifecycle Framework for Trustworthy AI in Medical Imaging From Transparent Data Governance to Clinically Validated Deployment. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.04249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brey, P.; Dainow, B. Ethics by design for artificial intelligence. AI Ethics 2024, 4, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ethical Domain | Key Risk | ML Lifecycle Stage | Technical Controls | Procedural/Governance Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy & Confidentiality [4,5,10,11,12,14,16,17,18] | Re-identification via narrative clues; incomplete de-identification | Data Collection, Deployment | Hybrid rule + ML de-identification; differential privacy; federated learning; synthetic data | Trusted Research Environments; continuous risk audits; access logging; ethics review |

| Bias & Fairness [19,20,21,22,23,24,25] | Stigmatizing or unequal documentation; under-representation of subgroups | Preprocessing, Model Development, Deployment | Fairness-aware learning; subgroup performance evaluation | Participatory design with clinicians/patients; bias audits; transparent model cards |

| Consent & Autonomy [26,27] | Lack of patient awareness or control over text use | Data Collection | – | Dynamic/meta-consent models; public registries; lay communication of data use; consent-to-contact mechanisms |

| Validity & Accountability [21,25] | Model opacity; poor generalizability; missing documentation | Model Development, Validation, Deployment | Explainable AI methods (SHAP, counterfactuals) | TRIPOD-AI/CONSORT-AI reporting; audit trails; external validation; algorithmic impact assessments |

| Governance & Stewardship [28,29] | Fragmented regulation; inequitable benefit distribution | All stages | – | Multi-stakeholder oversight; harmonized global standards (OECD, GDPR, HIPAA, TCPS2); ethics-by-design; capacity-building for LMICs |

| Framework/Guideline | Jurisdiction/Organization | Key Ethical Principles | Applicability to EMR Text | Relevant ML Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMIA Code of Ethics for Health Information Professionals (2021) [15] | International | Integrity, confidentiality, social responsibility | Stresses ethical literacy among informaticians | Guides training, ethical decision-making, and responsible reporting of ML outputs |

| WHO Guidance on Ethics and Governance of AI in Health (2023) [33] | World Health Organization | Accountability, inclusiveness, human oversight, sustainability | Global reference for AI/ML ethics; applicable to text analytics | Emphasizes ethics-by-design, participatory governance, human-in-the-loop oversight |

| OECD Recommendation on Health Data Governance (2017) [28] | OECD Members | Privacy, transparency, stewardship, interoperability | Promotes cross-national data-sharing ethics | Supports federated learning, standardized de-identification, multi-site validation |

| GDPR (2018) [46] | European Union | Lawfulness, fairness, transparency, purpose limitation, data minimization | Defines identifiable data broadly—applies to pseudonymized text | Requires careful de-identification, transparency, and lawful basis for ML training |

| TCPS 2 (2022) [32] | Canada | Respect for persons, concern for welfare, justice | Requires proportionate safeguards for re-identifiable EMR text | Dynamic/meta-consent models; ethics board oversight; risk-based de-identification |

| HIPAA Privacy Rule (1996) [48] | United States | Safe-harbor de-identification, expert determination, accountability | Limited guidance for narrative text—expert review required | Expert determination for free-text EMR; secure TREs; audit trails |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, G.; Yang, F. Ethical Considerations for Machine Learning Research Using Free-Text Electronic Medical Records: Challenges, Evidence, and Best Practices. Hospitals 2025, 2, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals2040029

Wu G, Yang F. Ethical Considerations for Machine Learning Research Using Free-Text Electronic Medical Records: Challenges, Evidence, and Best Practices. Hospitals. 2025; 2(4):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals2040029

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Guosong, and Fengjuan Yang. 2025. "Ethical Considerations for Machine Learning Research Using Free-Text Electronic Medical Records: Challenges, Evidence, and Best Practices" Hospitals 2, no. 4: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals2040029

APA StyleWu, G., & Yang, F. (2025). Ethical Considerations for Machine Learning Research Using Free-Text Electronic Medical Records: Challenges, Evidence, and Best Practices. Hospitals, 2(4), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals2040029