Effectiveness of Multidisciplinary Pre-Discharge Conferences on Concordance Rate in Place of End-of-Life Care and Death: A Single-Center Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

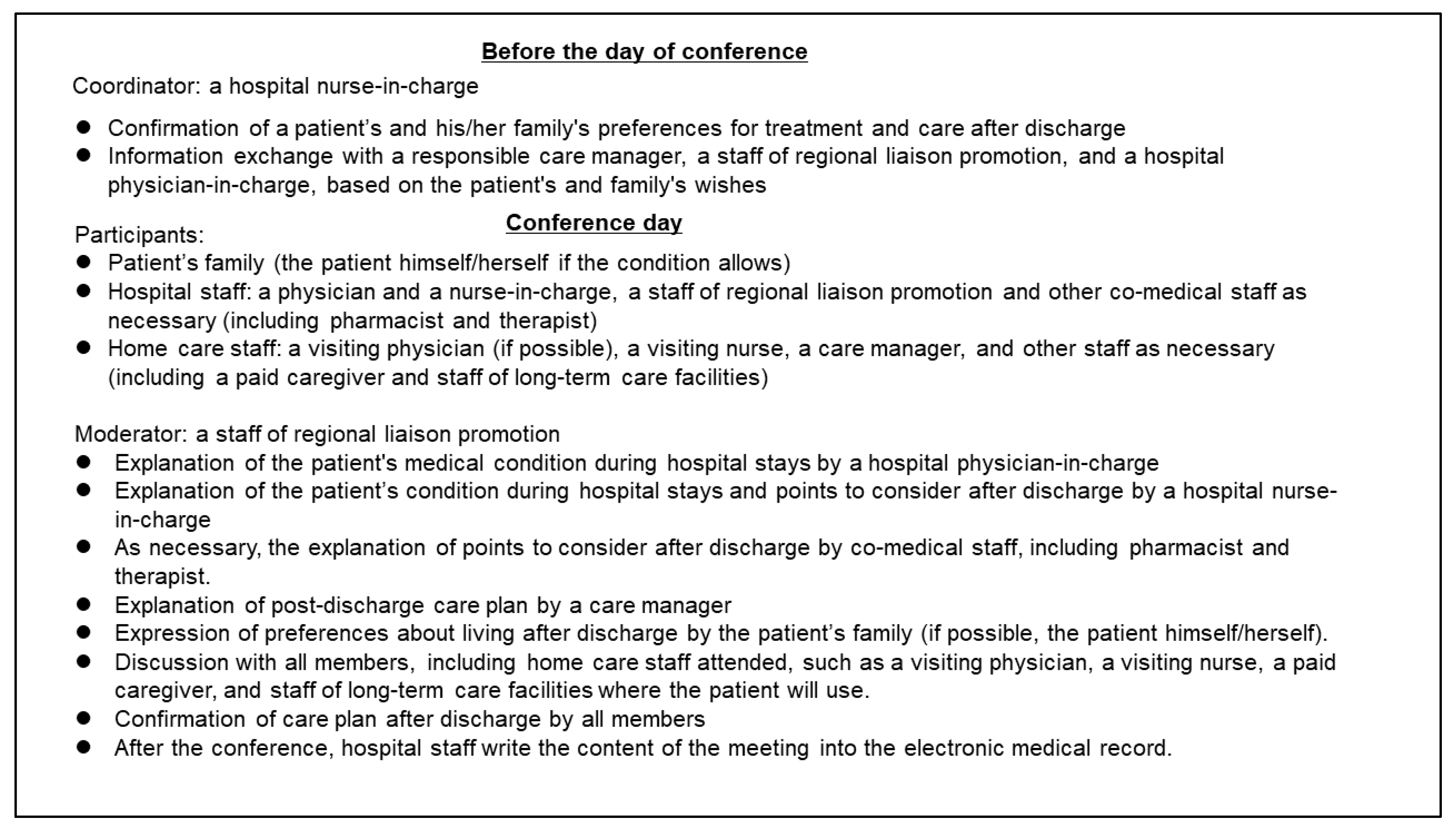

2.3. Routine Multidisciplinary Pre-Discharge Conference

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Follow-Up

2.6. Statistical Analyses

2.7. Research Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Baseline Patients’ Attributes between the Conference and Non-Conference Groups

3.2. Expression Rate of Preferred Place of End-of-Life Care

3.3. Patient and Family Concordance Rate of Preferred Place of End-of-Life Care and Place of Death

3.4. Factors Related to Death at Home (Table 4)

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age | 1.018 (0.992–1.045) | 0.184 | 1.019 (0.982–1.058) | 0.312 |

| Female | 0.943 (0.610–1.456) | 0.790 | 1.058 (0.591–1.894) | 0.848 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.934 (0.815–1.069) | 0.321 | ||

| BI | 0.995(0.985–1.004) | 0.245 | ||

| CFS | 1.031 (0.838–1.270) | 0.771 | ||

| Underlying diseases | ||||

| Malignant disease | 1.273 (0.811–1.998) | 0.294 | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.537 (0.289–0.997) * | 0.049 | 1.223 (0.558–2.678) | 0.615 |

| Dementia | 0.564 (0.302–1.053) | 0.072 | ||

| Neurologic disease | 1.370 (0.620–3.024) | 0.437 | ||

| Respiratory disease | 1.680 (0.776–3.636) | 0.188 | ||

| Heart disease | 1.463 (0.580–3.687) | 0.420 | ||

| Bone and joint disease | 2.771 (0.767–10.009) | 0.120 | ||

| Others † | 0.448 (0.166–1.207) | 0.112 | ||

| Cognitive Impairment | ||||

| Impaired | 0.464 (0.283–0.761) * | 0.002 | 0.610 (0.326–1.139) | 0.121 |

| Household structure | ||||

| Living alone | 0.626 (0.288–1.361) | 0.237 | ||

| Living with 1 person | 0.955 (0.585–1.558) | 0.852 | ||

| Living with more than 2 persons | 1.233 (0.783–1.941) | 0.367 | ||

| BMI | 0.922 (0.885–0.983) * | 0.013 | 0.904 (0.835–0.980) * | 0.014 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| Hgb | 1.070 (0.970–1.181) | 0.176 | ||

| TP | 0.806 (0.616–1.053) | 0.114 | ||

| Albumin | 0.804 (0.570–1.135) | 0.215 | ||

| sCr | 0.831 (0.634–1.089) | 0.179 | ||

| BUN | 0.998 (0.977–0.999) * | 0.028 | 0.994 (0.981–1.008) | 0.419 |

| C-reactive protein | 0.962 (0.927–0.999) * | 0.042 | 0.987 (0.943–1.032) | 0.561 |

| The number of admissions | 0.905 (0.799–1.025) | 0.115 | ||

| Patient preferences | 0.849 (0.588–1.228) | 0.385 | 0.993 (0.595–1.657) | 0.979 |

| Family preferences | 1.358 (1.029–1.790) * | 0.030 | 1.678 (1.155–2.438) * | 0.007 |

| Holding pre-discharge conference | 3.700 (2.343–5.842) * | <0.001 | 2.969 (1.682–5.239) * | <0.001 |

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. Statistical Handbook of Japan 2023. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/pdf/2023all.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Miura, H. Historical changes in home care service and its future challenges. Jpn. Med. Assoc. J. 2015, 58, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Umegaki, H.; Asai, A.; Kanda, S.; Maeda, K.; Shimojima, T.; Nomura, H.; Kuzuya, M. Factors associated with unexpected admissions and mortality among low-functioning older patients receiving home medical care. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roughead, E.E.; Kalisch, L.M.; Ramsay, E.N.; Ryan, P.; Gilbert, A.L. Continuity of care: When do patients visit community healthcare providers after leaving hospital? Intern. Med. J. 2011, 41, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurlo, A.; Zuliani, G. Management of care transition and hospital discharge. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.; Lannin, N.A.; Clemson, L.M.; Cameron, I.D.; Shepperd, S. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD000313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodakowski, J.; Rocco, P.B.; Ortiz, M.; Folb, B.; Schulz, R.; Morton, S.C.; Leathers, S.C.; Hu, L.; James, A.E., 3rd. Caregiver integration during discharge planning for older adults to reduce resource use: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bångsbo, A.; Dunér, A.; Lidén, E. Patient participation in discharge planning conference. Int. J. Integr. Care 2014, 14, e030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimla, B.; Parkinson, L.; Wood, D.; Powell, Z. Hospital discharge planning: A systematic literature review on the support measures that social workers undertake to facilitate older patients’ transition from hospital admission back to the community. Australas. J. Ageing 2023, 42, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmark, S.; Söderberg, S.; Skär, L. Information exchange between registered nurses and district nurses during the discharge planning process: Cross-sectional analysis of survey data. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2015, 40, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Harhara, T.; Athar, S.; Nair, S.C.; Kamour, A.M. Multi-Disciplinary Discharge Coordination Team to Overcome Discharge Barriers and Address the Risk of Delayed Discharges. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2022, 15, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altfeld, S.J.; Shier, G.E.; Rooney, M.; Johnson, T.J.; Golden, R.L.; Karavolos, K.; Avery, E.; Nandi, V.; Perry, A.J. Effects of an enhanced discharge planning intervention for hospitalized older adults: A randomized trial. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of the 2006 Medical Fee Revision. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2006/02/dl/s0215-3u.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Yokochi, K.; Wada, H.; Yamada, A.; Shigeta, T.; Aoki, M.; Suzuki, K. Discharge support practicies that strengthened the regional alliances-analysis of two cases effectively used of the discharge conference prior to a hospital discharge. Jpn. J. Cancer Chemother. 2009, 36, 153–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka, K.; Yoshizawa, A.; Yoshizawa, T.; Ikeda, H.; Moraita, S. Considering the Role of home Care Support Clinics at a Pre-Discharge Conference. Jpn. J. Cancer Chemother. 2019, 46 (Suppl. 1), 121–123. [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima, N.; Nagaoka, M. Evaluation of the pre-discharge conference before leaving in the acute hospital from a view point of a care manager. Bull. Grad. Sch. Health Sci. Akita Univ. 2019, 27, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, H.; Goto, Y. Impact of the Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score as a prognostic factor for all-cause mortality in older patients without cancer receiving home medical care: Hospital ward-based observational cohort study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e066121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinlich Heine Universität Düsseldorf. *Power: Statistical Power Analyses for Windows and Mac. Available online: https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower.html (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Nagae, H.; Tanigaki, S.; Okada, M.; Katayama, Y.; Norikoshi, C.; Nishina, Y.; Sakai, M. Identifying structure and aspects that c‘ontinuing nursing care’ used in discharge support from hospital to home care in Japan. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2013, 19 (Suppl. 2), 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulin, K.; Olsson, L.E.; Wolf, A.; Ekman, I. Person-centred care—An approach that improves the discharge process. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 15, e19–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masumoto, S.; Sato, M.; Ichinohe, Y.; Maeno, T. Factors facilitating home death in non-cancer older patients receiving home medical care. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 1231–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goossens, B.; Sevenants, A.; Declercq, A.; Van Audenhove, C. Shared decision-making in advance care planning for persons with dementia in nursing homes: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, B.; Sevenants, A.; Declercq, A.; Van Audenhove, C. Improving shared decision-making in advance care planning: Implementation of a cluster randomized staff intervention in dementia care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.S.; Meier, D.E.; Arnold, R.M. What’s wrong with advance care planning? JAMA 2021, 326, 1575–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, R.S. Advance Directives/Care Planning: Clear, Simple, and Wrong. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 878–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, R.; Guo, Z.; Wong, M. Confucian perspectives on psychiatric ethics. In The Oxford Handbook of Psychiatric Ethics; Sadler, J.Z., Fulford, K., van Staden, C.W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 603–615. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Qu, T.; Yang, J.; Ma, B.; Leng, A. Confucian Familism and Shared Decision Making in End-of-Life Care for Patients with Advanced Cancers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efraimsson, E.; Sandman, P.O.; Hydén, L.C.; Rasmussen, B.H. Discharge planning: F‘ooling ourselves’? -patient participation in conferences. J. Clin. Nurs. 2004, 13, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Article 12: Equal Recognition before the Law Paragraph 27. Available online: https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRPD/C/GC/1/Corr.1&Lang=en (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Goto, Y.; Miura, H.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Onishi, J. Evaluation of an advance care planning training program for practice professionals in Japan incorporating shared decision making skills training: A prospective study of a curricular intervention. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Valuables | Total | Holding Pre-Discharge Conference | No Pre-Discharge Conference | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 551) | (n = 244) | (n = 307) | ||

| Age y, median (IQR) | 83.0 (13) | 82.0 (13) * | 84.0 (12) | 0.027 |

| Female, n, (%) | 272(49.4) | 116 (48.5) | 156 (50.0) | 0.733 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 2.0 (2) | 2.00 (2) | 2.00 (2) | 0.467 |

| BI, median (IQR) (missing data = 88) | 5.0 (30) | 5.0 (26) | 5.0 (35) | 0.245 |

| CFS, median (IQR) (missing data = 60) | 8.0 (1) | 8.00 (1) | 8.00 (1) | 0.829 |

| Underlying diseases | ||||

| Malignant disease, n (%) | 155 (28.3) | 59 (24.2) | 96 (31.3) | 0.066 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 89 (16.2) | 42 (17.2) | 47 (15.3) | 0.546 |

| Dementia, n (%) | 78 (14.2) | 37 (15.2) | 41 (13.4) | 0.545 |

| Neurologic disease, n (%) | 71 (12.9) | 44 (18.0) * | 27 (8.8) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory disease, n (%) | 53 (9.4) | 25 (10.2) | 28 (9.1) | 0.656 |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 39 (7.1) | 11 (4.5) * | 28 (9.1) | 0.036 |

| Bone and joint disease, n (%) | 25 (4.5) | 7 (2.9) | 18 (5.9) | 0.093 |

| Others †, n (%) | 41 (7.4) | 19 (7.8) | 22 (7.2) | 0.783 |

| Cognitive Impairment (missing data = 104) | ||||

| Impaired, n (%) | 172 (38.3) | 81 (33.2) | 91 (29.6) | 0.669 |

| Household structure (missing data = 2) | ||||

| Living alone, n (%) | 61 (11.1) | 24(9.9) | 37(12.1) | 0.412 |

| Living with 1 person, n (%) | 151 (27.5) | 61 (25.1) | 90 (29.4) | 0.261 |

| Living with more than 2 persons (%) | 337 (61.4) | 158 (65.0) | 179 (58.5) | 0.119 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) (missing data = 73) | 18.3 (4.9) | 17.6 (4.5) * | 18.9 (5.3) | 0.012 |

| Laboratory findings, median (IQR) | ||||

| Hgb, g/dL (missing data = 11) | 11.4 (2.9) | 11.6 (2.7) * | 11.1(3.2) | 0.004 |

| TP, g/dL (missing data = 23) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.5 (1.1) | 0.718 |

| Albumin, g/dL (missing data = 20) | 3.2 (0.8) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.8) | 0.366 |

| sCr, mg/dL (missing data = 10) | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.4) * | 0.8(0.5) | <0.001 |

| BUN, mg/dL (missing data = 9) | 20.0 (16) | 18.00 (15) * | 21.0 (18) | <0.001 |

| CRP, mg/dL (missing data = 9) | 2.3 (7.3) | 2.3 (7.0) | 2.4 (7.6) | 0.818 |

| The number of admissions, median (IQR) | 1.0 (1) | 2.0 (2) * | 1.0 (1) | <0.001 |

| The number of deaths during study period, n (%) | 340 (61.7) | 150 (61.5) | 190(61.9) | 0.921 |

| Home death number in the deceased patients and rate (%) in total death | 136 (40.0) | 87 (58.0) * | 49 (25.8) | <0.001 |

| Patient (Total = 551) | Family (Total = 551) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conference (+), n = 244 | Conference (−), n = 307 | p Value | Conference (+), n = 244 | Conference (−), n = 307 | p Value | |

| PPEoLC | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Home | 119 (48.8) | 91 (29.6) | <0.001 | 136 (55.7) | 87 (28.3) | <0.001 |

| Outside Home | 12 (4.9) | 18 (5.9) | 44 (18.0) | 105 (34.2) | ||

| No expression or ambiguous | 113 (46.3) | 198 (64.5) | 64 (26.2) | 115 (37.5) | ||

| Expression rate (%) | 53.7 * | 35.5 | <0.001 | 73.8 * | 62.5 | 0.005 |

| Deceased Patient with Expressed PPEoLC (Total = 145) | ||||||

| Death Place of Conference (+), n = 81 | Death Place of Conference (−), n = 64 | |||||

| PPEoLC | Home | Outside Home | Concordance Rate | Home | Outside Home | Concordance Rate |

| Home, n (%) | 47 (100) | 27 (79.4) | 0.67 * | 20 (95.2) | 35 (81.4) | 0.42 |

| Outside Home, n (%) | 0 (0) | 7 (20.6) | 1 (4.8) | 8 (18.6) | ||

| Deceased Patients’ Family with Expressed PPEoLC (Total = 227) | ||||||

| Death Place of Conference (+), n = 113 | Death Place of Conference (−), n = 114 | |||||

| PPEoLC | Home | Outside Home | Concordance Rate | Home | Outside Home | Concordance Rate |

| Home, n (%) | 64 (91.4) | 18 (41.9) | 0.79 | 28 (82.4) | 15 (18.8) | 0.82 |

| Outside Home, n (%) | 6 (8.6) | 25 (58.1) | 6 (17.6) | 65 (81.3) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miura, H.; Goto, Y. Effectiveness of Multidisciplinary Pre-Discharge Conferences on Concordance Rate in Place of End-of-Life Care and Death: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Hospitals 2024, 1, 104-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals1010009

Miura H, Goto Y. Effectiveness of Multidisciplinary Pre-Discharge Conferences on Concordance Rate in Place of End-of-Life Care and Death: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Hospitals. 2024; 1(1):104-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals1010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiura, Hisayuki, and Yuko Goto. 2024. "Effectiveness of Multidisciplinary Pre-Discharge Conferences on Concordance Rate in Place of End-of-Life Care and Death: A Single-Center Retrospective Study" Hospitals 1, no. 1: 104-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals1010009

APA StyleMiura, H., & Goto, Y. (2024). Effectiveness of Multidisciplinary Pre-Discharge Conferences on Concordance Rate in Place of End-of-Life Care and Death: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Hospitals, 1(1), 104-113. https://doi.org/10.3390/hospitals1010009