Behind University Students’ Academic Success: Exploring the Role of Emotional Intelligence and Cognitive Test Anxiety

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Emotional Intelligence

1.2. Cognitive Test Anxiety

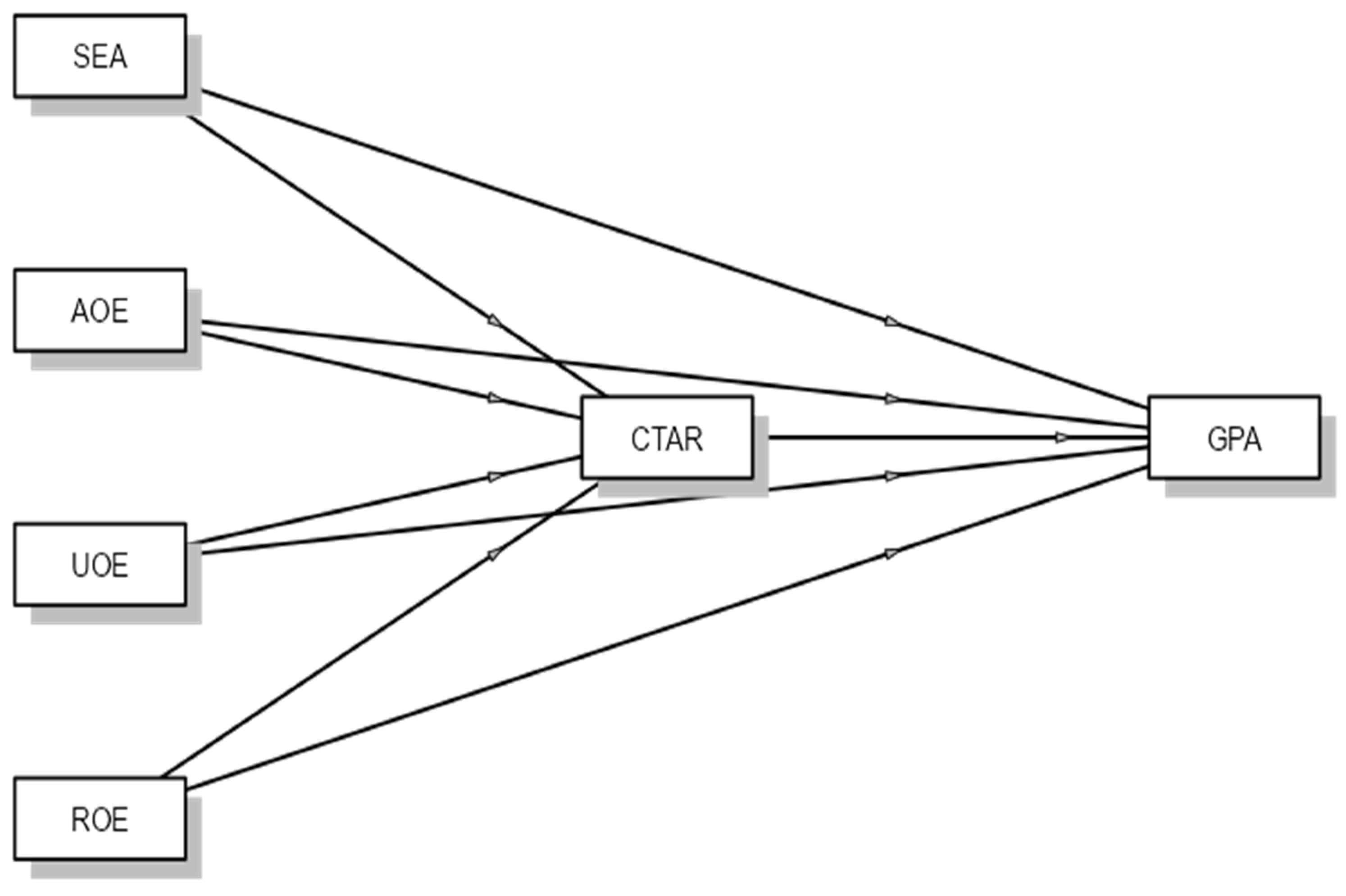

1.3. Current Study and Research Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Instruments and Measures

2.2.1. Emotional Intelligence

2.2.2. Cognitive Test Anxiety

2.2.3. Grade Point Average

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kyriakidis, A.; Zervoudakis, K.; Krassadaki, E.; Tsafarakis, S. Exploring the Impact of ICT on Higher Education Teaching During COVID-19: Identifying Barriers and Opportunities Through Advanced Text Analysis on Instructors’ Experiences. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 16, 11896–11926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiou, A.; Vasilaki, E.; Mastrothanasis, K.; Galanaki, E. Emotional Intelligence and University Students’ Happiness: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs’ Satisfaction. Psychol. Int. 2024, 6, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D. Models of Emotional Intelligence. In Handbook of Intelligence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 396–420. [Google Scholar]

- MacCann, C.; Jiang, Y.; Brown, L.E.R.; Double, K.S.; Bucich, M.; Minbashian, A. Emotional Intelligence Predicts Academic Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 150–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional Intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K.V.; Pita, R.; Kokkinaki, F. The Location of Trait Emotional Intelligence in Personality Factor Space. Br. J. Psychol. 2007, 98, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R. Emotional Intelligence: An Integral Part of Positive Psychology. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2010, 40, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, I.; Matheson, K.; Mantler, J. The Assessment of Emotional Intelligence: A Comparison of Performance-Based and Self-Report Methodologies. J. Personal. Assess. 2006, 86, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, C.; Stan, M.M.; Dumitru, G. Academic Support through Tutoring, Guided Learning, and Learning Diaries in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Experimental Model for Master’s Students. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1256960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, R. Emotional Intelligence: A Study on University Students. J. Educ. Learn. 2019, 13, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinauskas, R.; Malinauskiene, V. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Psychological Well-Being among Male University Students: The Mediating Role of Perceived Social Support and Perceived Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.D.A.; Summerfeldt, L.J.; Hogan, M.J.; Majeski, S.A. Emotional Intelligence and Academic Success: Examining the Transition from High School to University. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreopoulou, A.; Vasiou, A.; Mastrothanasis, K. The Role of Contact and Emotional Intelligence in the Attitudes of General Population Towards Individuals Living With Mental Illness. J. Community Psychol. 2025, 53, e23162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J. Emotions and Leadership: The Role of Emotional Intelligence. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albesher, S.A.; Alsaeed, M.H. Emotional Intelligence and Its Relation to Coping Strategies of Stressful Life Events among a Sample of Students from the College of Basic Education in the State of Kuwait. J. Educ. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 16, 273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fteiha, M.; Awwad, N. Emotional Intelligence and Its Relationship with Stress Coping Style. Health Psychol. Open 2020, 7, 2055102920970416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Thingujam, N.S. Emotional Intelligence: Theoretical Frameworks and Applied Implications. Indian J. Psychol. 2008, 23, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Marinaki, M.; Antoniou, A.-S.; Drosos, N. Coping Strategies and Trait Emotional Intelligence of Academic Staff. Psychology 2017, 8, 1455–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, M.; Matthews, G. Evaluation Anxiety: Current Theory and Research. In Handbook of Competence and Motivation; Elliot, A.J., Dweck, C.S., Eds.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.L.; Cassady, J.C.; Heller, M.L. The Influence of Emotional Intelligence, Cognitive Test Anxiety, and Coping Strategies on Undergraduate Academic Performance. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2017, 55, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Peterson, C.; Matthews, M.D.; Kelly, D.R. Grit: Perseverance and Passion for Long-Term Goals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H.; Zimmerman, B.J. Self-Regulation and Learning. In Handbook of Psychology; Reynolds, W.M., Weiner, I.B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cassady, J.C. Anxiety in the Schools: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions for Academic Anxieties. In Handbook of Stress and Academic Anxiety; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrothanasis, K.; Zervoudakis, K.; Kladaki, M.; Tsafarakis, S. A Bio-Inspired Computational Classifier System for the Evaluation of Children’s Theatrical Anxiety at School. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 11027–11050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surbakti, R.; Umboh, S.E.; Pong, M.; Dara, S. Cognitive Load Theory: Implications for Instructional Design in Digital Classrooms. Int. J. Educ. Narrat. 2024, 2, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassady, J.C.; Finch, W.H. Using Factor Mixture Modeling to Identify Dimensions of Cognitive Test Anxiety. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2015, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beilock, S. Choke: What the Secrets of the Brain Reveal about Getting It Right When You Have to; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Putwain, D.W.; Gallard, D.; Beaumont, J. A Multi-Component Wellbeing Programme for Upper Secondary Students: Effects on Wellbeing, Buoyancy, and Adaptability. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2019, 40, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogianni, A.; Vasilaki, E.; Linardakis, M.; Vasiou, A.; Mastrothanasis, K. Interactive Multimedia Environment Intervention with Learning Anxiety and Metacognition as Achievement Predictors. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M.W.; Derakshan, N.; Santos, R.; Calvo, M.G. Anxiety and Cognitive Performance: Attentional Control Theory. Emotion 2007, 7, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 43–71. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano Pintado, I.; Escolar Llamazares, M.d.C. Description of the General Procedure of a Stress Inoculation Program to Cope with the Test Anxiety. Psychology 2014, 5, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassady, J.C.; Finch, W.H. Revealing Nuanced Relationships Among Cognitive Test Anxiety, Motivation, and Self-Regulation Through Curvilinear Analyses. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S.T.; Hard, B.M.; Gross, J.J. Reappraising Test Anxiety Increases Academic Performance of First-Year College Students. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 110, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, N.; Freche, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zeller, G.; Carroll, I. Test Anxiety and Poor Sleep: A Vicious Cycle. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 28, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, J.; Peralta-Sánchez, F.J.; Martínez-Vicente, J.M.; Sander, P.; Garzón-Umerenkova, A.; Zapata, L. Effects of Self-Regulation vs. External Regulation on the Factors and Symptoms of Academic Stress in Undergraduate Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albulescu, I.; Labar, A.-V.; Manea, A.-D.; Stan, C. The Mediating Role of Cognitive Test Anxiety on the Relationship between Academic Procrastination and Subjective Wellbeing and Academic Performance. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1336002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadpanah, M.; Akbari, T.; Akhondi, A.; Haghighi, M.; Jahangard, L.; Sadeghi Bahmani, D.; Bajoghli, H.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Brand, S. Detached Mindfulness Reduced Both Depression and Anxiety in Elderly Women with Major Depressive Disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 257, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, R.; Padilla, A.M.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Rocamora, P.; Morales-Gázquez, M.J.; López-Liria, R. The Influence of Emotional Intelligence on Resilience, Test Anxiety, Academic Stress and the Mediterranean Diet. A Study with University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. What Is Emotional Intelligence? In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Educators; Salovey, P., Sluyter, D.J., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kafetsios, K.; Nezek, J.B.; Vasiou, A. A Multilevel Analysis of Relationships Between Leaders’ and Subordinates’ Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Outcomes. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 1121–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiou, A.; Mouratidis, A.; Michou, A.; Touloupis, T.; Psychountaki, M. Teachers’ Emotion Regulation and Anger Profiles as Predictors of Classroom Management Practices. Eur. J. Educ. 2025, 60, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeps, K.; Mónaco, E.; Cotolí, A.; Montoya-Castilla, I. The Impact of Peer Attachment on Prosocial Behavior, Emotional Difficulties and Conduct Problems in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Empathy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermitzaki, I.; Bonoti, F.; Kriekouki, M. Examining Test Emotions in University Students: Adaptation of the Test Emotions Questionnaire in the Greek Language. Hell. J. Psychol. 2016, 13, 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Sakka, S.; Nikopoulou, V.; Bonti, E.; Tatsiopoulou, P.; Karamouzi, P.; Giazkoulidou, A.; Tsipropoulou, V.; Parlapani, E.; Holeva, V.; Diakogiannis, I. Assessing Test Anxiety and Resilience among Greek Adolescents during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2020, 7, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trikoilis, D. Investigating the Factors Affecting Adolescents’ Test Anxiety in Greece during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pastor. Care Educ. 2024, 42, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.; Aybek, E. Jamovi: An Easy to Use Statistical Software for the Social Scientists. Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ. 2020, 6, 670–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-S.; Law, K.S. The Effects of Leader and Follower Emotional Intelligence on Performance and Attitude. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafetsios, K.; Zampetakis, L.A. Emotional Intelligence and Job Satisfaction: Testing the Mediatory Role of Positive and Negative Affect at Work. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008, 44, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassady, J.C.; Johnson, R.E. Cognitive Test Anxiety and Academic Performance. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 27, 270–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, I.G. Stress, Anxiety, and Cognitive Interference: Reactions to Tests. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putwain, D.W.; von der Embse, N.P. Teachers Use of Fear Appeals and Timing Reminders Prior to High-Stakes Examinations: Pressure from above, below, and Within. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 21, 1001–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Embse, N.P.; Kilgus, S.P.; Segool, N.; Putwain, D. Identification and Validation of a Brief Test Anxiety Screening Tool. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 1, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.K.; Al Sabbah, S.; Al-Jarrah, M.; Senior, J.; Almomani, J.A.; Darwish, A.; Albannay, F.; Al Naimat, A. The Mediating Effect of Digital Literacy and Self-Regulation on the Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Academic Stress among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gómez, A.; Luna, P.; García-Diego, C.; Rodríguez-Donaire, A.; Cejudo, J. Exploring the Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention in University Students: MindKinder Adult Version Program (MK-A). Eval. Program Plan. 2023, 97, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmi, C. Integrating Social Emotional Learning Strategies in Higher Education. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, P.A.; Morina, N. Exploring the Association of Social Comparison with Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2020, 27, 640–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, P.; Isham, A.E.; Zachariae, R. The Association between Empathy and Burnout in Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Zolkoski, S. Preventing Stress Among Undergraduate Learners: The Importance of Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, and Emotion Regulation. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, T.; Palmer, E.; Palmer, D. Flexible Assessment and Student Empowerment: Advantages and Disadvantages—Research from an Australian University. Teach. High. Educ. 2024, 29, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustis, E.H.; Williston, S.K.; Morgan, L.P.; Graham, J.R.; Hayes-Skelton, S.A.; Roemer, L. Development, Acceptability, and Effectiveness of an Acceptance-Based Behavioral Stress/Anxiety Management Workshop for University Students. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2017, 24, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, E. Effects of Cognitive Behavioral Group Program for Mental Health Promotion of University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. Impact of Arts Activities on Psychological Well-Being: Emotional Intelligence as Mediator and Perceived Stress as Moderator. Acta Psychol. 2025, 254, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, A.; Goetz, T.; Krannich, M.; Donker, M.; Bieleke, M.; Caltabiano, A.; Mainhard, T. Control, Anxiety and Test Performance: Self-reported and Physiological Indicators of Anxiety as Mediators. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 93, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiou, A.; Vasilaki, E. Cracking the Code of Test Anxiety: Insight, Impacts, and Implications. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honicke, T.; Broadbent, J. The Influence of Academic Self-Efficacy on Academic Performance: A Systematic Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 17, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Duan, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zhu, L. The Interplay of Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Emotion Regulation Strategies in College Students. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2025, 49, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiou, A.; Andriopoulou, P. University Students’ Mental Health and Affect during COVID-19 Lockdown in Greece: The Role of Social Support and Inclusion of Others in the Self. Psychol. J. Hell. Psychol. Soc. 2023, 28, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WLEIS | SEA | AOE | UOE | ROE | CTAR | GPA | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WLEIS | — | |||||||

| SEA | 0.82 * | — | ||||||

| AOE | 0.62 * | 0.42 * | — | |||||

| UOE | 0.77 * | 0.49 * | 0.31 * | — | ||||

| ROE | 0.77 * | 0.55 * | 0.23 * | 0.47 * | — | |||

| CTAR | −0.35 * | −0.34 * | −0.04 | −0.34 * | −0.30 * | — | ||

| GPA | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.12 | −0.02 | −0.20 ** | — | |

| Age | 0.17 *** | 0.20 ** | 0.06 | 0.17 *** | 0.06 | −0.16 *** | 0.03 | — |

| Mean | 5.13 | 5.26 | 5.55 | 5.11 | 4.60 | 2.27 | 8.00 | 23.35 |

| SD | 0.71 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 0.69 | 0.74 | 6.73 |

| 95% C.I. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

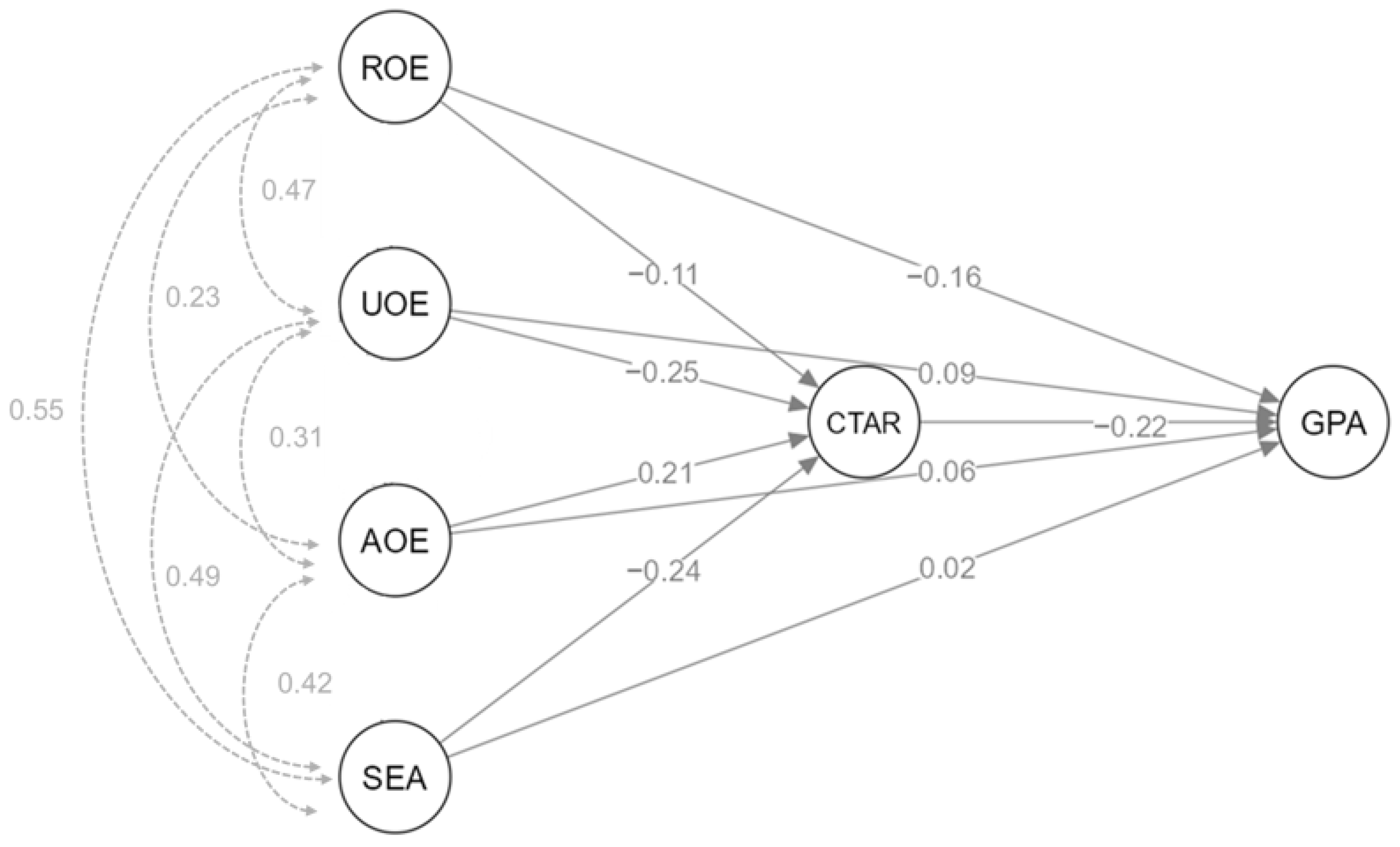

| Type | Effect | Estimate | SE | LL | UL | β | z | p |

| Indirect | SEA ⇒ CTAR ⇒ GPA | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.94 | 0.052 |

| AOE ⇒ CTAR ⇒ GPA | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0 | −0.05 | −2.02 | 0.043 | |

| UOE ⇒ CTAR ⇒ GPA | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 2.10 | 0.036 | |

| ROE ⇒ CTAR ⇒ GPA | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.21 | 0.228 | |

| Component | SEA ⇒ CTAR | −0.17 | 0.06 | −0.30 | −0.05 | −0.24 | −2.72 | 0.007 |

| CTAR ⇒ GPA | −0.24 | 0.09 | −0.41 | −0.07 | −0.22 | −2.78 | 0.005 | |

| AOE ⇒ CTAR | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 2.95 | 0.003 | |

| UOE ⇒ CTAR | −0.17 | 0.05 | −0.27 | −0.07 | −0.25 | −3.21 | 0.001 | |

| ROE ⇒ CTAR | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.18 | 0.03 | −0.11 | −1.34 | 0.181 | |

| Direct | SEA ⇒ GPA | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.14 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.856 |

| AOE ⇒ GPA | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.09 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.72 | 0.473 | |

| UOE ⇒ GPA | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 1.05 | 0.295 | |

| ROE ⇒ GPA | −0.11 | 0.06 | −0.24 | 0.01 | −0.16 | −1.78 | 0.075 | |

| Total | SEA ⇒ GPA | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.71 | 0.476 |

| AOE ⇒ GPA | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.13 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.889 | |

| UOE ⇒ GPA | 0.11 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 1.68 | 0.093 | |

| ROE ⇒ GPA | −0.10 | 0.06 | −0.22 | 0.03 | −0.14 | −1.49 | 0.137 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vasiou, A.; Vasilaki, E.; Mastrothanasis, K.; Gkontelos, A. Behind University Students’ Academic Success: Exploring the Role of Emotional Intelligence and Cognitive Test Anxiety. Trends High. Educ. 2025, 4, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4030056

Vasiou A, Vasilaki E, Mastrothanasis K, Gkontelos A. Behind University Students’ Academic Success: Exploring the Role of Emotional Intelligence and Cognitive Test Anxiety. Trends in Higher Education. 2025; 4(3):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4030056

Chicago/Turabian StyleVasiou, Aikaterini, Eleni Vasilaki, Konstantinos Mastrothanasis, and Angelos Gkontelos. 2025. "Behind University Students’ Academic Success: Exploring the Role of Emotional Intelligence and Cognitive Test Anxiety" Trends in Higher Education 4, no. 3: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4030056

APA StyleVasiou, A., Vasilaki, E., Mastrothanasis, K., & Gkontelos, A. (2025). Behind University Students’ Academic Success: Exploring the Role of Emotional Intelligence and Cognitive Test Anxiety. Trends in Higher Education, 4(3), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4030056