1. Introduction

The point of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives is to create fairer and more inclusive workplaces and communities by actively addressing historical and systemic disadvantages faced by marginalized groups. Diversity refers to the representation of people from many communities, identities, races, ethnicities, backgrounds, abilities, cultures, lifestyles, and beliefs, including those who may be historically excluded or underrepresented [

1]. Equity refers to fairness in treatment and the availability of, and access to, supports and opportunities [

2], and for clarity, equity is not the same as equality. Whereas equality provides all people with the same treatment, equity recognizes that people face different barriers, thus requiring different supports and opportunities to reach the same goal. Finally, inclusion refers to the degree to which all members of a community are recognized and able to use their talents [

3].

DEI is currently the subject of heated debate and tremendous vitriol in the United States, which has created unprecedented stress across higher education. Subsequently, a number of campus DEI offices have been shuttered and programs canceled, resulting in employees leading DEI efforts and providing resources to students experiencing layoffs or job reassignments. In January 2025, an executive order signed by U.S. President Trump declared that DEI policies and programs adopted by colleges, universities, and others can violate federal civil rights laws [

4]. To date, over 50 U.S. universities are under investigation as part of the anti-DEI crackdown, with several seeing cuts in funding, with McGowan et al. [

5] explaining that the current challenge lies not only in defending DEI efforts but also in reimagining them so as to maintain efficacy and resilience during these politically volatile times.

Despite the current controversy, DEI scholars advocate that institutions with a commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion should evaluate their praxes recognizing that campuses should strive to be inclusive communities that celebrate diversity, and which provide fair and equitable access to opportunities to all community members [

6]. Further, campuses should explore whether their teaching and learning experiences provide mirrors, windows, and doors, have cultural validity, afford multiple mechanisms for student success, are centered around the assets of students, build knowledge, extend perspectives, and foster empathy [

7].

This paper discusses research conducted at a Mid-Atlantic minority-serving university with a commitment to DEI envisioned as one of the institutional goals. The institution is a Historically Black College or University (HBCU) located in a state system that also has a strategic plan that prioritizes diversity, equity, and inclusion with goals that include the conduct of research on DEI, promoting best practices to enhance inclusion and endorse equity, and nurturing culturally responsive teaching and DEI education that encourages students to be informed and engaged citizens [

6]. More specifically, the study presented here explored whether all community members consider the campus inclusive, whether all community members experience a culture of belonging, whether adequate resources and supports exist for all campus members to succeed, whether faculty exhibit culturally responsive teaching practices, and whether the perceptions of faculty and staff differ from those of students.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: a Literature Review, Materials and Methods, Results, Discussion, Limitations, and Conclusions. The literature review discusses DEI in higher education, culturally responsive teaching, HBCUs and DEI, and influential theories. The goal of the authors is for this paper to contribute to the literature on DEI, especially on the role that minority-serving institutions can play, while also encouraging other institutions to engage in similar DEI climate studies.

3. Materials and Methods

A state university system, located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, has a strategic plan that prioritizes diversity, equity, and inclusion with goals that include the conduct of research on DEI, promoting best practices to enhance inclusion and endorse equity, and nurturing DEI education that encourages students to be informed and engaged citizens. Among these system institutions is a minority-serving HBCU that has also committed to justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI) with activities that include evaluating and assessing current programming and services; introducing a JEDI institutional learning goal and supporting general education requirement; using surveys to measure faculty, student, and staff perceptions; and exploring culturally responsive practices throughout teaching and learning. Accordingly, in 2024, a quality improvement project was proposed that involves the development, delivery, and reporting of a comprehensive JEDI needs assessment of the community using a mixed-methods approach.

A paper has been published [

6] that discusses in detail the instrument design and validation process. In sum, a thirteen-step process was identified.

Identification of goals

Establishment of research questions

Review of literature and existing tools

Consultation with experts

Identification of Methodology

Preparation of draft instruments

Check of readability and face validity

Expert panel review

Institutional Review Board review and approval

Pilot study

Distribution and data collection

Analysis and reporting of findings

Internal validity testing and use of results

A series of research questions were established around which the study was designed

Do all community members consider the campus inclusive?

Do all community members experience a culture of belonging?

Are there adequate resources and supports for all campus members to succeed?

Do faculty exhibit culturally responsive teaching practices?

Do faculty and staff differ in their perceptions?

Two surveys were created in the Survey Monkey system, one for faculty and staff and the other for students. The faculty and staff surveys were purposed to explore the campus climate with respect to JEDI; participant demographics; engagement in JEDI activities; infusion of culturally responsive teaching strategies for teaching faculty; and recommendations and needs. The student survey was designed to explore the campus climate; participant demographics; engagement in campus JEDI activities, resources, and services; reflections on their courses; perspectives and experiences related to their work, study, and participation in the campus community; the identification of obstacles and barriers to inclusion; and recommendations and needs.

The surveys included a combination of dichotomous, Likert-scaled, multiple-response, ratio, short-answer, and contingency questions. A number of experts were consulted during the instrument design process and the draft instrument was reviewed by two separate carefully curated expert panels prior to IRB approval and conduction of the pilot. Question design was influenced by the literature and similar studies, the consideration of available instruments, recommendations by the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education, and consultation with experts. The culturally responsive teaching questions were informed by the literature including the checklist published by Buzzetto-Hollywood [

7].

Expert panelists were required to agree to an informed consent statement and were provided with instructions. They were asked to review questions grouped topically and were provided with prompts following each question group where they could provide feedback as they analyzed and assessed the quality of the questions and survey design, response options, structure, and overall methodology to ensure the instrument effectively captured the intended data and avoided biases. Expert panelists were also prompted to provide additional feedback and identify improvements needed.

The pilot was conducted in September 2024 with 24 individuals who completed the survey and then participated in focus groups where they reflected upon and provided feedback on the instruments. More specifically, participants were asked to analyze the questions and question flow, assess how well the survey will meet expectations, reflect upon the length of the questionnaire, consider instances where there may be confusion, etc. Response time was also examined and compared to what had been previously estimated by the Survey Monkey system. As a result of the pilot, some clarifying information was provided in the surveys, the estimated time for completion was adjusted, and the wording of a question was altered.

Prior to distribution, a sample size calculator was utilized with the confidence interval set to 95% and the margin of error set to 5%. Based on the calculation, the desired sample size for students was 342 and the recommended sample size for faculty and staff was 227.

The student survey was launched first and occurred over three weeks in late October and early November 2024. A one-time mass email was sent to all students at the university; however, the email only resulted in about 50 responses. As planned, flyers were placed across campus to increase awareness of the project and the researchers who had acquired hundreds of free promotional t-shirts strategically visited courses selected to ensure that the population would be representative of the student body. In total, 455 students completed the survey, representing a response rate of 15% and exceeding the 342-participant sample size recommended.

For the faculty and staff survey, human resources provided a list of all faculty and staff emails which were loaded into the Survey Monkey system, and the Email Invitation Collector was utilized. The list included approximately 700 emails; however, a significant number of those emails were duplicates, several were linked to deceased individuals or people who had departed from the university, and a number resulted in bounce backs. In total, 104 individuals responded to the email invitation, representing a response rate of 14% out of the 700, although in actuality the response rate was much larger (adjusted to 19%) as approximately 150 of the emails were either duplicates, individuals no longer affiliated with the institution, or unreachable email addresses. Nevertheless, the recommended participant sample of 227 was not reached.

After data collection was concluded, the data was imported to SPSS, version 30 where descriptive statistical analyses including the mean, standard deviation, frequency distribution, and confidence interval were calculated. Reliability testing was conducted using Cronbach’s alpha application. Chi-square tests, which are a common inferential statistical test used to examine the differences between categorical variables, were conducted. Chi-square tests aim to determine if a difference between observed data and expected data is due to chance or if it is due to a relationship between the variables. Finally, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were prepared to determine whether there is a monotonic component of association between continuous or ordinal variables. Monotonic relationships occur when one thing goes up or down with the other.

4. Results

Established in 1886, the University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES) is a Historically Black, 1890 land grant institution. It is a member of the University System of Maryland and primarily serves first-generation, low-income, and minority learners. The student population is approximately 3200 as of the fall of 2024, with an 88% minority student enrollment. The acceptance rate for applying students is approximately 61%, with the majority of students coming from the Mid-Atlantic region, more specifically, the Baltimore and Washington D.C. urban centers. UMES has a long history of providing academic programs and services for ethnically and culturally diverse students and, towards that end, offers programs and assistance that attract, serve, retain, and graduate many first-generation college students [

6].

In total, 455 students completed the survey as well as 104 faculty and staff. The demographics are represented in

Appendix A in

Table A1 and

Table A2. According to the analysis of the demographic responses, 88% of the student respondents were between the ages of 18–24, about 89% were non-white, 83% were born in the United States, 74% identified as straight or heterosexual, 92% identified as cisgender, 51.9% were female, and 41% were male, with the rest either preferring not to say or identifying as nonbinary or gender fluid. About 43.5% of respondents identified as a first-generation college student, which is a student whose parent(s) or guardian(s) did not complete a four-year bachelor’s degree. Approximately 54.7% identified as Christian, and another 10.2% as Catholic. A total of 12.6% preferred not to say, 12% responded “other,” 9% were atheist or agnostic, and the remaining 10.5% of respondents were split among the World’s remaining major religions. Seventy-nine percent of student respondents were first-time undergraduates, around 5% were graduate students, and approximately 15% were undergraduate adult learners. The student demographics were accurately reflective of the student body of the institution, although the percentage of graduate students was disproportionately low.

With respect to the faculty and staff demographics, 32% of respondents reported that they were white, 77% were United States citizens, 76% reported being straight or heterosexual, 99% identified as cisgender, 61.5% were female, and 32.7% were male, with the rest either preferring not to say or identifying as nonbinary or gender fluid. Approximately 16.3% were tenured faculty, 20.2% were non-tenured faculty, 5.8% were adjuncts, 43.3% were staff, and 13.5% were administrators. When it came to religion, 39.5% identified as Christian or Protestant, 12.5% as agnostic or atheist, 11.5% as Catholic, 11.5% as spiritual but not religious, 10.6% preferred not to say, 5.8% as Islamic, and the remaining 8.6% were split among the World’s remaining major religions.

Cronbach’s alpha, also known as tau-equivalent reliability or coefficient alpha, is a reliability coefficient and a measure of the internal consistency of tests and measures. Cronbach’s alpha is the correlation between the answers in a questionnaire and can take values between 0 and 1. The higher the average correlation between items, the greater the internal consistency of a test, as follows:

Excellent: A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.9 or higher.

Good: A Cronbach’s alpha between 0.8 and 0.9.

Acceptable: A Cronbach’s alpha between 0.7 and 0.8.

Questionable: A Cronbach’s alpha between 0.6 and 0.7.

Poor: A Cronbach’s alpha between 0.5 and 0.6.

Unacceptable: A Cronbach’s alpha below 0.5.

The standard Cronbach’s alpha, which calculates reliability based on the average shared variance between items, and the Cronbach’s alpha based on standardized items, which calculates reliability based on the average inter-item correlation, were conducted. The analyses found all question sets to be in either the acceptable, good, or excellent range, These results are depicted in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

A series of Likert scaled agreement questions looked at student satisfaction with the campus experience via a series of statements where 1 equaled strongly disagree and 5 equaled strongly disagree. The overall mean for the student group was 3.72 with an SD= 1.01 and CI = 0.091. The overall mean for the faculty and staff group was 4.04 with an SD = 1.098 and CI = 0.196. Reflections on the campus experience are represented in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Students were asked about the campus climate with respect to their overall satisfaction via a series of questions utilizing a scale of 1 to 5 where 1 equaled extremely dissatisfied and five equaled extremely satisfied, μ = 3.53, SD = 1.01, and CI = 0.09; and whether the campus is free from strain related to individual or group differences, μ= 3.59, SD = 0.875, and CI = 0.08. Faculty and staff were also asked about their overall satisfaction with the campus climate with the same scale, where μ = 3.75, SD = 1.09, and CI = 0.209; and whether the campus is free from strain related to individual or group differences where μ = 3.60, SD = 0.88, and CI = 0.209. Results are shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6.

Respondents were asked their perceptions of the representation of different cultural groups. Students responded that there was adequate representation of different cultures on campus, μ = 3.73, SD = 0.908, and CI = 0.083, including the Indigenous people that once lived on the land that is now the campus, μ = 3.28, SD = 0.960, and CI = 0.088. Faculty and staff reported similar perceptions of the representation of different cultural groups, μ = 3.53, SD = 1.08, and CI = 0.208, but were more negative when it came to the representation of the Indigenous people that once lived on the land that is now the campus, μ = 2.76, SD = 1.12, and CI = 0.216. Results are presented in

Table 7 and

Table 8.

With the results represented in

Table 9, students were asked to reflect on their experiences at UMES: whereas 11.5% have personally experienced discrimination at UMES, 21.4% have witnessed discrimination against someone else at UMES, 17.5% have personally experienced harassment at UMES, and 25% have witnessed harassment against someone else. When asked “If you have witnessed or heard someone, make an insensitive or disparaging remark about a person or people based on their age, race, ethnicity, gender identify, or disability status from where did it come?” the responses were faculty (15%), students (43.8%), staff (15.5%), administrator (8.3%), and local community member (11.5%). When it comes to the targets of bias, the most commonly cited were people based on LGBTQIA+ status (23.8%), gender identity or expression (15%), race (12%), gender (10.2%), foreign-born people (7.6%), ethnicity (7.2%), not being religious (7%), and religious affiliation (6.3%).

Faculty and staff participants were also asked to reflect on their experiences at UMES with the results presented in

Table 10: whereas 29% have personally experienced discrimination at UMES, 41% have witnessed discrimination against someone else at UMES, 24% have personally experienced harassment at UMES, and 30% have witnessed harassment against someone else. When asked “If you have witnessed or heard someone, make an insensitive or disparaging remark about a person or people based on their age, race, ethnicity, gender identify, or disability status from where did it come?” the responses were faculty (29.8%), students (36.2%), staff (23.1%), administrator (12.5%), and local community member (13%). When it comes to the targets of bias, the most commonly cited were people based on race (25%), gender (21.2%), LGBTQIA+ status (17.3%), being foreign-born (17.3%), not being religious (14.4%), ethnicity (12.5%), and gender identity or expression (11.5%).

- R1

Do all community members consider the campus inclusive?

Student participants were asked to rank the UMES campus community for inclusivity on a sliding scale where 0 equaled extremely hostile and not inclusive and 100 equaled extremely inclusive. According to the analyses and with the results represented in

Table 11, a mean of 65.1 was achieved with an SD of 21.74 and a CI of 1.97. Faculty and staff respondents were also asked to rank the UMES campus community for inclusivity on the same sliding scale. According to the analyses, and with 102 people responding, a mean of 71.85 was achieved with an SD of 21.51 and a CI of 4.05.

- R2

Do all community members experience a culture of belonging?

Presented in

Table 12 and

Table 13, perceptions of belonging were measured. Student perceptions of belonging were explored through three agreement questions where 1 equaled strongly disagree and 5 equaled strongly disagree, μ = 3.51, SD = 0.969, and CI = 0.088. Meanwhile, faculty and staff perceptions of belonging were explored through two agreement questions where people were asked if all members of the UMES community experience a sense of belonging (μ = 3.11, SD = 1.13, and CI = 0.217) and if the campus frequently has events designed to promote belonging (μ = 3.29, SD = 1.15, and CI = 0.221).

- R3

Are there adequate resources and supports for all members of the campus to succeed?

Student perceptions of supports are presented in

Table 14 and were explored through a nine agreement question series where μ = 3.49, SD = 0.954, and CI = 0.087. Faculty and staff perceptions of supports are presented in

Table 15 and were explored through an eight agreement question series where μ = 3.13, SD = 1.12, and CI = 0.212.

Students reflected upon the adequacy of a number of resources for supporting minoritized populations where μ = 3.51, SD = 0.868, and CI = 0.0794. These results are presented in

Table 16.

- R4

Do faculty exhibit culturally responsive teaching practices?

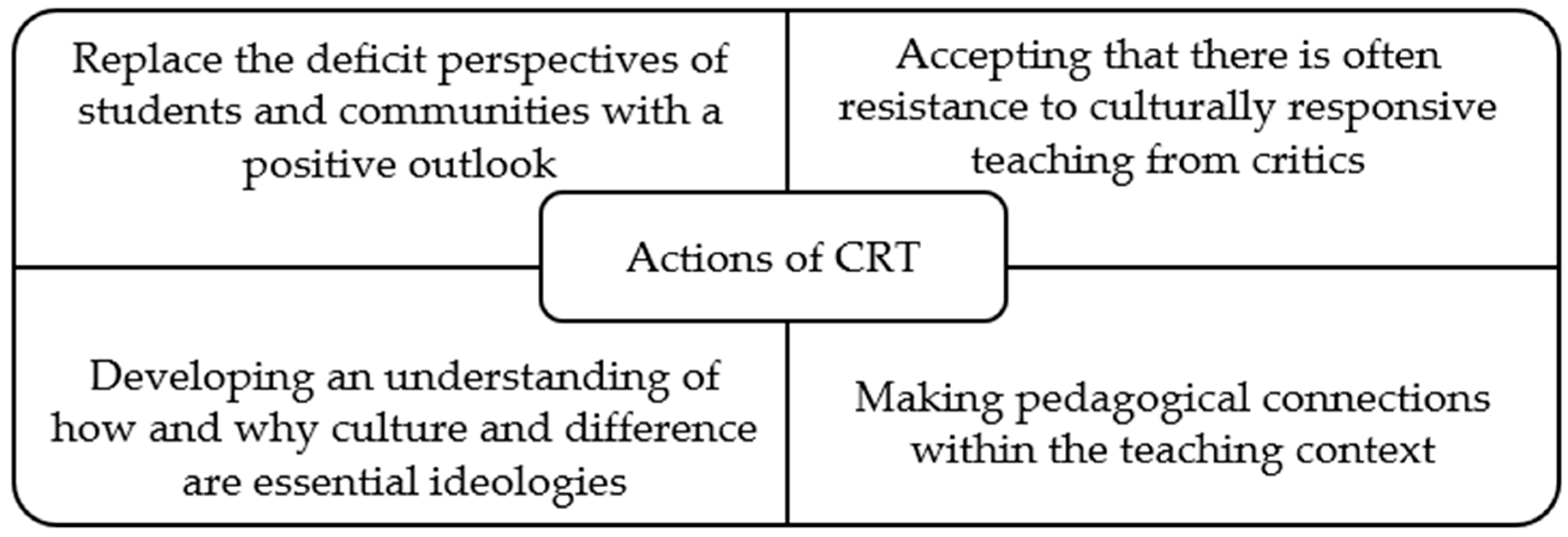

Culturally responsive teaching practices are strategies in which the students’ unique cultural strengths are identified and nurtured to promote student achievement and a sense of well-being [

7]. Eight Likert-scale agreement questions were used to measure the culturally responsive teaching experiences of students where μ = 4.00, SD = 1.08, and CI = 0.206. Results are presented in

Table 17.

Culturally responsive teaching is also known as culturally compatible, culturally appropriate, culturally congruent, and/or culturally relevant teaching [

7]. Fifteen Likert-scale agreement questions were used to measure culturally responsive teaching of faculty respondents where μ = 4.00, SD = 1.08, and CI = 0.206. Only faculty were given these questions with the responses displayed in

Table 18.

- R5

Do faculty and staff differ in their perceptions?

Analyses were run to consider differences among faculty and staff and student responses with respect to respondent perceptions of inclusiveness and campus climate satisfaction. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients also known as Spearman’s Rho were prepared to determine whether there is a monotonic component of association. Monotonic relationships occur when one thing goes up or down with the other. Chi-squares were also conducted. A chi-square is a common inferential statistical test used to examine the differences between categorical variables. This test aims to determine if a difference between observed data and expected data is due to chance or if it is due to a relationship between the variables. The Spearman’s rank-order correlations did not find a strong, positive correlation, rs = 0.128 and

p = 0.003, and rs = 0.107 and

p = 0.012. With respect to the chi-square, significance was also not found when it came to perceived inclusivity,

p = 0.106, but significance was found when satisfaction with the campus climate was considered,

p = 0.002. These findings are presented in

Table 19.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore DEI and culturally responsive teaching on the campus of a Historically Black College or University (HBCU) located in the Mid-Atlantic United States, via a comprehensive DEI climate study. The goal of the study was to help address the gap in the DEI literature with respect to the practices of minority-serving institutions. Two surveys were created, one for students and another for faculty and staff. Survey creation involved a comprehensive review of the literature and existing studies and instrumentation, and consultation with experts. Survey drafts went through two separate carefully curated expert panels prior to IRB approval and the conduction of pilot testing.

Prior to distribution, a sample size calculator was utilized with the confidence interval set to 95% and the margin of error set to 5%. Based on the calculation, the desired sample size for students was 342 and the recommended sample size for faculty and staff was 227. In total, 455 students completed the survey along with 104 faculty and staff. After data collection was concluded, descriptive statistical analyses including the mean, standard deviation, frequency distribution, and confidence interval were conducted. Reliability testing was also conducted using Cronbach’s alpha application, and chi-square tests and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were prepared.

Based on consideration of the means, standard deviations, and confidence intervals, student participants indicated that the University is inclusive with most students expressing that all community members experience a sense of belonging. Faculty and staff respondents were more strongly positive in their opinion that the university is inclusive and were also in agreement that all members of the community experience a sense of belonging. These findings are in agreement with what has been reported in the literature: that HBCUs are unparalleled as exemplars of DEI [

7,

54,

55] that should serve as a model for institutions across the globe with a commitment to inclusivity [

47]. These results are also explained with social cognitive theory and psychological safety theory where learning involves an interplay between our beliefs, expectations, environmental influences, self-efficacy, and relationships; and individuals thrive in environments where they feel safe to express themselves without fear [

6,

48,

51].

Most students expressed that they have experienced adequate support and resources; however, faculty and staff were more tempered regarding the adequacy of supports and resources. More specifically, a negative perception was indicated when it came to support for disabled and transgender members of the campus community. Faculty also expressed dissatisfaction regarding the representation of Indigenous people on the UMES campus. These finds are consistent with what has been reported by Herr-Perrin [

47] who points out that despite being designed as “sanctuaries of inclusivity in the midst of an otherwise hostile society, HBCUs are not flawless DEI models and are also impacted by such issues as discrimination towards LGBTQIA+ students and other threats to inclusion and belonging.” From a theoretical perspective, the negative perceptions expressed can be related to multiple minority stress and, more specifically, intersectional theory, which explains that people belonging to multiple minority groups often face compounding and intersecting stressors [

50].

When culturally responsive teaching practices were explored, both students and faculty responded in strong agreement. In terms of culturally responsive teaching practices, these findings provide valuable confirmation of what is already expressed in the literature, which has reported that HBCUs have an unparalleled longstanding history of culturally responsive teaching practices that were in place decades before the term was formally introduced [

6,

7,

47]. As Brock and Slater [

46] explained, this is because HBCUs have cultivated “humanistic” environments for student learning where students recognize that they are valued, resulting in a strong sense of belonging being felt by students, meaningful relationships between faculty and students, and an overall commitment to equity. Further, these findings support the theory of critical pedagogy which posits that issues of social justice are not distinct from teaching and learning and that education can influence social transformation by encouraging learners to challenge oppressive structures and become agents of change [

53].

When an effort was made to explore whether perceptions of faculty and staff differ significantly from those of students, Spearman’s rank-order correlations and chi-square significance tests were performed. The Spearman’s rank was not significant, and chi-square did not find significance when it comes to perceived inclusivity, but significance was found when satisfaction with the campus climate was considered. Overall, and due to the self-selection bias and the non-statistically significant population size of the faculty and staff respondents, this line of exploration is considered both inconclusive and unreliable.

To inform the institution and elicit recommendations, a short-answer qualitative question was added to each survey asking how the institution could better support DEI and cultivate a culture of belonging and inclusion. Semantic analysis was conducted using two methods. First, the semantic analysis AI tools in Survey Monkey were utilized, which include a thematic analysis tool that uses machine learning to automatically categorize text responses and generate themes. Second, the researchers engaged in a human controlled manual semantic recoding and categorization process. The results of both methods were compared for similarity and to finalize themes. When thematic analysis and semantic recoding were performed on students’ responses, the most common themes included hosting more community events or activities, more LGBTQIA+ supports, more awareness and commitment, conducting listening sessions or town halls, and offering more training or workshops. The themes generated from the student short-answer responses are represented in

Table 20.

When thematic analysis and semantic recoding were performed on faculty and staff responses, the most common themes included more celebrations of diversity, workshops or professional development, more commitment to DEI, greater support for culturally responsive teaching and JEDI course content, less religion or emphasis on Christian values, and incentives for faculty. The themes generated from the faculty and staff short-answer responses are represented in

Table 21.

7. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to help address the gap in the DEI literature exploring the practices of HBCUs and other types of minority-serving institutions. According to the results, participants found the University to be an inclusive place, expressing strong satisfaction with the campus climate and experience. Further, when the presence of culturally responsive teaching practices was explored, strong evidence was indicated. Possible areas for improvement include greater supports and resources for LGBTQIA+, Indigenous, and disabled community members.

Thyden et al. [

56] postulate that while Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were founded on antiracism, many predominantly White institutions (PWIs) were founded on exclusionary tactics that uphold white supremacy. They explain that, as a result, Black students at HBCUs experience less structural racism than Black students at PWIs with increased social supports [

56,

57] and more positive student mental health outcomes [

58]. At the same time, some scholars point out that HBCUs may exist within a larger “white supremacist society” [

56] as indicated by underfunding when it comes to state, federal, and private money, which impacts all aspects of the teaching, learning, and overall student experience [

59,

60]. Additionally, the success of HBCUs occurs despite Black students at HBCUs arriving on these venerated campuses with lower high-school grades, lower standardized test scores, and parents with less education and lower incomes compared with Black students at majority-serving institutions [

61].

In order to dive deeper into a number of important topics and themes that emerged from this investigation, a series of focus groups and a town hall are currently being planned on the UMES campus. It is hoped that these listening and investigative sessions will engender meaningful critical discourse that results in tangible action items that can be implemented by the institution.

It is the goal of the authors for this paper to contribute to the body of literature on DEI in higher education. It is also hoped that this paper will inspire more institutions to engage in similar DEI climate studies. Instruments that have performed well when reliability testing was conducted have been introduced and are being made available by the authors for free usage provided proper attribution is given. More campuses need to engage in comprehensive climate studies in order to evaluate whether their campuses are inclusive communities where all members experience a sense of belonging, supports and resources promote equity, diversity is celebrated, and culturally responsive teaching is embraced.