Abstract

School development is important in society. This study investigates how questions work as an information carrier between different levels in a school organization. The questions are organized in a hierarchy, with the regional steering committee’s overarching question at the top and then distributed further on to the municipalities to interpret the questions that engage with their practice management. At the bottom of the hierarchy are the schools, and they create the final professional research questions that engage with day-to-day practice. Previous studies show that supporting and challenging each other can lead to the development of new knowledge in the organization. This is an empirical study based on documents with questions from the three levels (regional, municipal, and school). The questions were collected and the content in the questions was analyzed. The results show that it is possible to develop an organization by asking development-related questions, from top to bottom, in a hierarchical organization. However, problems arise when the developing questions require interpretation, and the interpretation leads to the shifting of the original goal. In this study, the aim at regional-level students and knowledge/learning was shifted to a focus on teachers and teaching especially at school level.

1. Introduction

In Sweden, as in many other countries, the goal of improving student performance in schools is an ongoing and frequently discussed issue. Students’ achievements are rarely as comprehensive and successful as society expects. This is particularly evident in public discussions when international assessments such as the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) and TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) reveal declining results compared to other countries, and in various studies, e.g., Ref. [1] point to different factors contributing to the declining test results across several subjects in Sweden. However, in the early 2010s, such discussions were often referred to as the so-called “PISA crisis” [2], which arose due to worsened results. Consequently, numerous development projects were initiated. In the subsequent PISA assessment of 2018, there was a slight improvement in Sweden’s results; however, by 2022, the results declined once again (though still above the OECD average). The primary issue is that an increasing number of students are performing worse in the percentiles that had already previously shown the weakest results in earlier PISA assessments [3].

Considering these international survey results, five municipalities in southern Sweden initiated a joint project to explore whether their schools could achieve better results through collaboration. The project aimed to formulate development questions with the goal of enhancing students’ knowledge. This article focuses on this regional development project, which lasted for three years and involved teachers, principals, school developers, and operations managers from the four municipalities in southern Sweden that ultimately participated in the project. One of the key aspects of the project and its organization was that the questions raised by the highest leadership within the organization were intended to drive development at the school level. The article primarily focuses on how participants at different organizational levels interpreted these questions and the consequences this had for potential school development.

2. Background

A project involving collaboration between multiple groups necessitates a structured organization, and the structure of the organization influences the participants. However, the extent to which participants are affected depends partly on how the project’s purpose is interpreted.

2.1. Governance of an Organization

Schools in Sweden, as in many other countries, are expected to function as evolving organizations, e.g., [3]. This expectation includes, among other aspects, the ambition to develop the organizational structure to establish new ways of collaborating. However, such collaborations and the anticipated development do not occur automatically; in most cases, specific goals must be formulated either within certain parts of the organization or across the entire organization. In order for this development to be realized, leadership is required.

Organizational governance can be implemented in various ways. For example, Audet and Roy [4] employed the strategic community (SC) approach, where different professional groups communicate through a bottom-up perspective based on feedback from participants to the organization’s leadership. However, Tsai and Beverton [5] advocate for a top-down organizational model, particularly within higher education, arguing that an organization driven by individual actors risks becoming chaotic, making a top-down approach more efficient. Sales et al. [6] further emphasize that capacity building within hierarchical organizations presents an even greater challenge due to tensions between theory and practice. Another method of governance involves the use of policy documents, such as national curricula mandated by the government [7] or more universally goal-oriented documents developed from a grassroots level [8].

Regardless of the governance model, information must be effectively communicated between different decision-making levels and among the individuals involved. In all organizations, the flow of information between participants is essential but also presents challenges, e.g., [4,9]. The effectiveness of information exchange across organizational levels is therefore crucial when working on a shared development project. If information is vaguely formulated, there is a risk of misinterpretation, e.g., [10,11], potentially leading to misunderstandings among participants. However, a well-functioning organizational structure alone is not sufficient to drive a project forward—leadership is also required.

2.2. Organizational Change and Leadership

Modifying an organization’s operations and objectives requires not only an organizational plan but also leadership, as change is an ever-present element affecting all organizations [12]. This assertion implies that change is inevitable; it will occur regardless of whether it is desired or not. Change is an inherent part of organizational life, both at operational and strategic levels [13], and is often driven by structural factors influenced by external forces. However, in some cases, changes are initiated internally by the organization’s own actors. Research suggests that individuals within an organization must be open to change [14], particularly in educational institutions [15,16].

During a change process, it is crucial for individuals to feel included and to have opportunities to influence the course of events. This is closely linked to empowerment and the recognition by the organizational leadership of what is essential can be framed as. Empowering people means partly removing obstacles to change and eliminating or modifying systems or structures that undermine the vision, as well as encouraging risk-taking, new ideas, and innovative activities [17]. Therefore, leadership is a decisive factor in organizational change [14].

2.3. The Importance of Communication in Leadership

For leadership to effectively influence an organization, efficient communication is essential. When an organization is undergoing change, it is therefore critical that the leadership’s intentions are clear in order to achieve the desired outcome, e.g., [16]. A well-defined communication structure is thus vital in ensuring a clear focus. Without it, intentions may be lost in ambiguous formulations, leading to vague interpretations.

There are numerous examples where leadership within schools, as well as in other organizations, has served as a positive force for development initiatives, e.g., [15,18,19,20]. Communication is, therefore, a key determinant of successful development-oriented change [21]. Marsh et al. [22] argue that if communication is viewed as an investment requiring time, it is possible to establish a shared understanding through dialogue. These substantive conversations enable organizations to continue working toward meaningful goals and improvements. However, the opposite is often more common—where leadership fails to communicate its objectives effectively, particularly because communication has not been anchored through discussions with those responsible for implementing the changes.

2.4. Purpose and Research Question

The purpose of this study is to examine how questions originating from management levels are interpreted, understood, and developed within a regional school development project. The research question supporting this objective is the following: How are guiding questions developed within a top-down organization in a regional cooperation project involving several actors?

3. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework is divided into three key areas:

- How is learning situated? (Section 3.1);

- How can collaboration lead to development? (Section 3.2);

- Can questions contribute to learning, or do they merely indicate progress? (Section 3.3).

3.1. Learning

The theoretical foundation of this study is partly situated within the sociocultural field, e.g., [23], as it encompasses both oral and written communication—written in the form of questions used in organizational communication and oral within the various collaborative groups discussing these questions. These discussions serve as an arena for knowledge development itself. Supporting and challenging one another can lead to new ideas, which are essential for constructing new knowledge, e.g., [24,25].

Additionally, this study draws on a social constructivist perspective, as individuals develop their understanding through interaction with the world around them [26]. When faced with a new situation, people rely on their prior experiences and conceptions (assimilation) before constructing new ideas (accommodation) [27,28]. However, in order to stimulate new thoughts, it is crucial to have a language capable of conveying knowledge. Language is a performative act—it becomes real and functional when expressed in spoken or written form [29]. Through language, social relationships, structures, and norms are established and maintained [30]. This construction of ideas within relationships is typically built upon spoken or written language, yet verbal and written interaction has dimensions beyond mere words [31].

Kozulin [32] summarizes the sociocultural context of cognitive theory using three metaphors: the worker, the poet, and the scientist. Similar to a worker, Dewey’s student acquires practical habits and skills that contribute to individual development, with experience—gained through direct engagement in educational projects—serving as the key to this learning process. Such extensive experience prepares students for the future. Vygotsky, like a poet, framed the mastery and internalization of language (symbolic psychological tools in society) while creating texts. These texts both preserve and transcend existing language by introducing new cultural expressions. Piaget, akin to a scientist, describes how students explore the physical and social universe through independent experimentation, resulting in logical systems applicable to empirical material.

3.2. Collaboration

Communication is a fundamental starting point for achieving organizational goals. However, in order to realize these goals, collaboration is often required among participants both within and outside the organization. A significant portion of public administration consists of municipalities, within which schools represent a substantial sector. Lu and Hallinger [33] examined how collaboration and constructive controversy among leadership teams can facilitate operational-level cooperation. Conducting survey research among staff in Hong Kong primary schools, they found that collaboration among leadership team members was positively associated with teacher collaboration.

However, leadership is not the only challenge when initiating a collaborative project—members must also be actively involved in the development process, prioritize agreed-upon commitments, and be willing to network with each other to achieve sustainable collaboration. Additionally, participants must remain engaged in the collaboration to ensure successful outcomes, e.g., [25,34].

Collaboration can be both beneficial and challenging, depending on the established habits and loyalties within an organization. One issue within the Swedish school context is managing the balance between municipal ambitions and their quality assurance systems in relation to schools’ relatively autonomous role as knowledge providers. These demands may sometimes lead to conflicts of loyalty, particularly in organizations such as preschools and schools, where leadership is often more non-hierarchical [35].

3.3. Questions as a Form of Communication

The use of questions is common in everyday educational settings, e.g., [36]. However, employing questions as a governance tool in an organization is less conventional, and relatively few studies have explored this approach. Thus, this study critically examines the use of questions as an instrument of governance from an educational perspective.

In classroom settings, questions are often used to confirm students’ understanding of complex subject matter, e.g., [37], but they also serve to generate interest [38]. There is also a strong connection between questioning, thinking, and learning when questions are posed to a class or other audiences, e.g., [39].

One of the most common questioning structures is the Initiation–Response–Evaluation (IRE) model, e.g., [40,41,42], in which an individual (leader, teacher, or other) initiates a question, another person responds, and the answer is subsequently evaluated—typically by the questioner. An alternative approach involves using open-ended questions that require students to formulate longer responses than the initial question itself. Open-ended questions facilitate deeper interaction between students and teachers, enhancing learning outcomes [43]. However, the use of questions to promote interaction between teachers and students is less common in university classrooms [44].

Furthermore, there are differences in how questions are handled depending on whether they are self-generated (i.e., internally motivated within a personal context) or imposed (i.e., formulated by one person and assigned to another for resolution). Imposed questions are the most prevalent, particularly in structured settings such as libraries, where they are frequently used among adults [45].

Another dimension of questioning in educational environments involves their use as a governance tool in workplace organizations. This study focuses on imposed (or assigned) questions and how they are interpreted in light of the broader understanding of schools and their students.

4. Methods

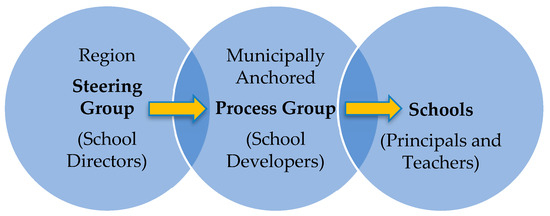

This study is based on collected texts from various groups, specifically the development questions formulated as different groups processed inquiries originating from the management level of the organization (Figure 1). These questions have been analyzed qualitatively through content analysis. In total, approximately 150 individuals participated in the formulation of these questions.

Figure 1.

Overview of the flow of questions through the organization.

4.1. Study Context

At the highest level of the organization is the regional steering group, where the executive management formulated the overarching question for the project:

“How can we enable and support our students to reach their optimal capacity in school—and thereby increase their goal attainment?”

This question was forwarded to the process group, which consisted of school development professionals from different municipalities. The process group refined, interpreted, and adapted the regional steering group’s question to align with more local challenges. This process resulted in new questions, which were then distributed to schools, where the groups primarily consisted of principals and teachers.

At the school level, the questions were further interpreted and subsequently examined within schools and preschools (referred to as the school level). The questions formulated at the school level are thus linked to those developed at both the regional and municipal levels (Figure 1).

To support school staff in this analytical process, a course on analytical competence was provided by university researchers. This initiative aimed to bridge the gap between theory and practice, a challenge highlighted by scholars such as Sales et al. [6].

This article primarily focuses on the development questions designed to strengthen and support students’ capacity building and how these questions manifest within a collaborative project in a top-down organizational structure.

4.2. Data Collection

The regional steering group clarified the project’s purpose by formulating a research question. The following question was documented in meeting minutes and published on the project’s official website:

“How can we enable and support our students to reach their optimal capacity in school—and thereby increase their goal attainment?”with the following clarification:“Reducing the gap between children’s/students’ capacity and what we manage to get them to achieve.”

The school developers in the process group interpreted the steering group’s question based on their respective municipality’s practices and policies. Each municipality developed questions for the three educational levels: preschool (ages 1–6), compulsory school (grades 1–9, ages 7–16), and upper secondary/adult education (from ages 16 with no limit). These questions were collected by the school developers in the process group and documented in written records. During the first year, the process group compiled the questions from the municipalities. In the second and third years, some municipalities modified their questions; however, in general, only minor clarifications of the original research question were made. These changes were also documented in the process group’s meeting records.

Finally, the questions were interpreted at the school level. The school-level groups consisted of at least one host from the school or preschool that formulated the problem and three individuals from other municipalities, referred to as critical friends. All participants at the school level were active within preschool, compulsory school, or upper secondary/adult education, and the majority were principals or teachers. However, in some groups, members from the health team (such as school nurses) also participated. The questions provided by the steering group and the school developers in the process group were now to be refined into a researchable question. The formulation of the final research question—and, in some cases, its subsequent investigation—was conducted as a collaborative project between the host and the critical friends.

The group work took place both during the course on analytical competence and in at least one additional session outside the course framework. One of these sessions was recorded. Each group then wrote a report at the end of the project, summarizing the insights gained from the course. Additionally, each group created a poster summarizing their investigation. The analytical competence course—and thus the yearly project cycle—concluded with a conference where the participating groups presented their findings to other course participants, the steering group, and policymakers from the school administrations. During this final conference, the posters were presented by the participants.

Over the three years, a total of 34 groups participated (Table 1). The university researchers collected the schools’ research questions from each school collaboration group, along with project reports and conference posters.

Table 1.

Number of schools participating over the three years of the project.

4.3. Analysis

The empirical material was analyzed using content analysis [46]. Content analysis has been widely used in various studies; for example, Arsenijević et al. [47] employed a similar approach to examine different aspects of knowledge management in organizations. In this study, the content analysis was based on the participants’ documented written questions. Zhang and Wildemuth [48] describe content analysis in several stages, and here we outline how we applied six of these steps.

- Step 1: All questions at all organizational levels were read.

- Step 2: Verification that all questions were relevant to the research.

- Step 3: Categorization of the questions. Two key content areas emerged from the “Research Object” and “Impact on”. The “Object of Investigation” category was further divided into three subcategories: work organization, and well-being.

- Step 4: The questions from the municipalities’ steering groups were tested.

- Step 5: The schools’ questions were categorized. The three researchers independently tested the categories.

- Step 6: Coding assessments were conducted, and conclusions were drawn.

In this study, we analyzed how the questions were formulated without considering whether the meaning was accurately reflected in relation to what was actually investigated. Furthermore, we did not interpret implicit or unspoken meanings in the groups’ questions; instead, we analyzed only the exact wording of the formulated questions.

5. Results

5.1. Steering Group Question

The question formulated by the regional steering group was as follows:

“How can we enable and support our students to reach their optimal capacity in school—and thereby increase their goal attainment?”with an additional clarification as follows:“Reducing the gap between children’s/students’ capacity and what we manage to get them to achieve.”

This question frames students as the object of investigation and emphasizes the goal of enhancing their ability to acquire more knowledge and learning. However, the question is challenging to answer and investigate, as it is difficult to determine a student’s actual capacity. The regional steering group’s question is therefore more relevant as an ambition rather than as an empirically investigable question. Another key issue is whether the definition of capacity pertains solely to students or also includes teachers and their teaching; how should the term “support” be interpreted?

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the project results, their interpretation, as well as the project conclusions that can be drawn.

5.2. Process Group’s Research Questions

The regional steering group’s question was then interpreted by the members of the process group. The process group, consisting of school developers from various municipalities, adapted the questions to fit their respective municipalities. The categorization of these research questions and the results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the research questions formulated by school developers in the process group, with some examples of the questions.

The analysis of the process group’s compilation of the municipality-adapted research questions revealed a concretization of the regional steering group’s question. However, it also showed that several questions were formulated to convey information about the school situation in different municipalities—meaning that they were framed more as an inventory of the schools’ starting points rather than forward-looking inquiries. The focus on students was rarely prioritized in the questions. While students might have been implicitly included in the questions, they were not explicitly stated, and in this analysis, only explicit formulations were considered.

Some questions explicitly mentioned children and students, such as “How do we succeed in creating a flexible learning environment based on children’s needs?” In this case, the students (children) were clearly stated, with the intended outcome being a change in the school organization.

Two questions were difficult to categorize under either “Research Object” or “Impact on,” as one did not investigate anything nor provide any information about what was intended to be examined. The other question had the formulation “How do we succeed...?” but did not specify according to whom or what.

Minor adjustments to the question formulations were made over the three years of the project, but these did not affect the categorization in Table 2.

5.3. Schools’ Researchable Questions

The research questions formulated at the school level had to consider not only the questions established by the process group and the steering group but also the requirement that they be investigable (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of the research questions from schools, Year 1, with some examples of the questions.

During the first year, schools chose to focus more on the research objects of teachers and school organization rather than directly on students. The areas of impact were evenly distributed across the three categories: knowledge and/or learning, teaching, and other factors.

At the school level, a clear issue emerged regarding how participants interpreted the questions from the steering and process groups. The formulated questions primarily focused on teaching and teachers rather than on students in schools or children in preschools. An example of this is the following: “How can we (teacher) see that the school adopts an investigative approach?” with the addition “How is this visible in teaching practices?” Similar to the school developers’ questions in the steering group, it is implied that quality learning will take place for students, but this is not explicitly stated in the research questions. A key challenge at this level is that the questions must not only address the operations but also be investigable within the school setting. Additionally, they must align with the questions posed by the steering group and the process group. One issue highlighted in one of the recorded discussions was the definition of various concepts in the questions originating from the steering group and the process group. For instance, there was debate over the definition of optimal capacity from the steering group and investigative development culture from one of the school developers in the process group. The problem was that no precise definitions were provided for participants to refer to, making the project’s direction difficult to interpret based on the given research questions.

During the second and third years of the project, empirical data continued to be collected from school reports and posters. To ensure a clearer focus on students and children in schools and preschools, it was emphasized during the analysis competence course that the questions needed to be more centered on children, students, and their learning and knowledge development. Despite this, schools’ interpretations of the questions from the steering and process groups continued to focus more on teachers and teaching. However, there was a shift in content regarding the category of other factors. Some groups began addressing issues such as well-being and discipline problems. The ambition in all groups remained that the questions and corresponding research should ultimately benefit students’ learning. However, the extent to which the questions explicitly addressed students, their learning, and their knowledge remained relatively limited (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4.

Summary of schools’ research questions, Year 2.

Table 5.

Summary of schools’ research questions, Year 3.

6. Discussion

The overall ambition of the project was to develop an organizational structure that provides schools with the necessary conditions to enhance students’ knowledge levels. To achieve this, and thus guide the organization, questions were formulated and passed from one level to another within the hierarchy. The ultimate goal was for schools to independently formulate researchable questions and subsequently investigate them using research-based methods to improve school development processes. All groups involved in the work actively collaborated with the intention of improving school practices. In this regard, the project successfully engaged the entire organization in a structured questioning process, as well as in investigating these questions [49].

However, as the questions were transferred from one level to another within the hierarchical organization, the project’s objectives became increasingly ambiguous. It is crucial to communicate leadership decisions, particularly in hierarchical structures, so that participants are aware of what is expected of them, as reported by Harris & Jones [16]. The findings of this study highlight the difficulties that arise when one hierarchical level attempts to direct the next without clearly defining the objectives. The regional steering group formulated the following question: “How can we strengthen and support our students so that they reach their optimal capacity in school—and thereby improve their performance?” along with the following clarification: “Reducing the gap between students’ capacity and what we manage to get them to achieve.”

This question, however, lacks a definition of what is meant by “the gap.” The question framers had the opportunity to refer to the description provided in the PISA report [2] but did not do so. Additional clarifying questions that could have been beneficial for schools to consider include the following: How do we determine that students are underperforming? Are all students underperforming? When does an individual perform at their optimal capacity? A different type of communication—one that is more knowledge-driven—could potentially have provided a solution. Supermane and Mohd Tahir [50] argue that communication is rarely discussed in relation to knowledge dissemination. It might have been more beneficial if the main question had focused explicitly on the specific knowledge that was expected to improve.

6.1. Hierarchical Challenges and Conflicting Agendas

School developers in the process group had to navigate at least two agendas: the regional steering group’s objectives and the policies set by their respective municipalities. These dual loyalties created a complex situation for school developers. However, such tensions are an inherent part of municipal governance. A key finding in this study, as well as in previous research, is that a conflict exists between making decisions based on knowledge derived from school practices and following directives from various actors within the professional education sector—a conflict previously highlighted by Håkansson [35].

This tension becomes even more pronounced as schools must align their work with the predetermined objectives and research questions formulated by the steering and process groups. Marsh et al. [22] argue that effective leadership invests in communication and strives to facilitate rich discussions to foster shared understanding. Had communication played a greater role within a flatter organizational structure, schools would likely have had better conditions for achieving meaningful goals and implementing measures to improve education. It would therefore have been more productive to invest further in communication within the project. The questions raised by the schools’ collaborative groups indicate that schools are highly engaged in examining how they can advance their professional practices.

6.2. Questions as Steering Mechanisms and Performative Acts

The different hierarchical levels had good intentions in formulating research questions. However, the fundamental purpose of a question (or multiple questions) is to direct subsequent levels. This means that each level must interpret the question based on its own contextual reality. The struggle to interpret these questions can be frustrating for participants, particularly when the questions are vague or difficult to operationalize. One of these issues appears in the shift from students/children to teachers in the questions. It is easier to investigate teachers and change teaching than evaluate the effects on the students in a project that is limited in time.

Another challenge is that questions function in a performative manner [29]. Formulating a question does not merely aim to investigate a specific issue but can also create new ways of thinking about a problem—or even introduce a problem that had not previously been considered. This dynamic is especially relevant when dealing with questions posed from a higher level in the hierarchy.

The questions distributed across different levels were open-ended. Bernard et al. [43] explain that open-ended questions provide more opportunities for interaction among those collaborating on them. The collaborative nature of these discussions enabled group members to engage with questions that reflected their respective realities. Ideally, the shift in the formulation of the research questions across hierarchical levels is a result of collaboration groups expanding their knowledge and, consequently, incorporating new terminology—expressions that reflect the conditions of the surrounding society and produce empirical material, akin to Kozolin’s [32] metaphor of “the worker, the poet, and the scientist.”

6.3. Methodology Discussion

The study is limited in that it includes a small number of groups and a restricted set of questions that were analyzed. Nevertheless, it reveals a trend indicating how the meaning of questions shifts as participants attempt to interpret those that are positioned higher in the hierarchy. Content analysis inherently involves interpretation of what people write. In this study, however, we chose not to interpret the participants’ intended meanings, but instead focused solely on the written responses. This approach can be seen as both a strength and a limitation. The categorization was based on an initial coding conducted by the three researchers involved in the project, meaning that the analysis reflects the interpretations of three different individuals.

7. Conclusions and Implications for Future Development

One of the most valuable outcomes of this project is its demonstration of the importance of regional collaboration in school development. The study suggests that fostering a regional approach to educational development in general might be more beneficial than focusing solely on improving students’ knowledge and learning, as originally framed by the regional steering group. A more inclusive and communication-driven strategy between the three levels could provide schools with better opportunities to refine their pedagogical practices, ultimately benefiting students’ learning experiences in a more practical and meaningful way. However, if a more extensive communication occurred between the different hierarchical levels, the shift in focus—from, for example, the students/children to the teachers—would not have taken place.

Author Contributions

P.G.E. have processed the empirical data and been primarily responsible for writing the article. J.S. has processed the theory section. Both authors have reviewed the final text and participated in evaluating the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The municipalities of Halmstad, Kungsbacka, Laholm, Varberg and Region of Halland—funded 30% of the research time.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study. This research project follows the ethical guidelines set by the Swedish Research Council [51]. All participants were informed about the project and provided their consent to participate. The Swedish Research Council [51] explicitly states that all participants must have the opportunity to approve or decline participation in research at any time during the data collection process and that all personal data must be anonymized. All participants were over 18 years old, no personal data was collected in this study, and participants were given the option to withdraw from participation at any time.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data contained in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Annette Johnsson who was a research colleague in this project but sadly passed away in January 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fredriksson, U.; Karlsson, K.-G.; Pettersson, A. PISA Under 15 år: Resultat och Trender. [PISA for 15 Years: Results and Trends]; Natur och Kultur: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2012 Results: What Makes Schools Successful? Resources, Policies and Practices (Volume IV); PISA; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2022 Results: Factsheets Sweden. 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/publication/pisa-2022-results/country-notes/sweden-de351d24#chapter-d1e11 (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Audet, M.; Roy, M. Using strategic communities to foster inter-organizational collaboration. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2016, 29, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.; Beverton, S. Top-down management: An effective tool in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2007, 21, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, A.; Moliner, L.; Amat, A.F. Collaborative professional development for distributed teacher leadership towards school change. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. Former. Sch. Organ. 2017, 37, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, N. When transnational curriculum policy reaches classrooms—Teaching as directed exploration. J. Curric. Stud. 2018, 50, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennehy, D.; Fitzgibbon, M.; Carton, F. International Development: Exploring the Gap Between Organisations’ Development Policy and Practice—A Southern Perspective. AI Soc. 2013, 29, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, J. Modelling the impact of knowledge management using technology. OR Insight 2010, 23, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkheimer, J.; Heide, M.; Nothhaft, H.; von Platen, S.; Simonsson, C.; Andersson, R. Is Strategic Communication too important to be left to Communication Professionals? Managers’ and coworkers’ attitudes towards strategic communication and communication professionals. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguley, M.; Kerby, M.; MacDonald, A.; Cruickshank, V. Strangers on a train: The politics of collaboration. Aust. Educ. Res. 2021, 48, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todnem By, R. Organisational change management: A critical review. J. Change Manag. 2005, 5, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnes, B. Managing Change: A Strategic Approach to Organisational Dynamics, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, R. Change management—Or change leadership? J. Change Manag. 2002, 3, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M. (Eds.) Leading Futures: Global Perspectives on Educational Leadership; SAGE Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M. Leading schools as learning organizations. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2018, 38, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. The New Rules: How to Succeed in Today’s Post-Corporate World; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven Strong Claims About Successful School Leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2008, 28, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Seashore, K.; Anderson, S.; Wahlstrom, K. Review of Research: How Leadership Influences Student Learning; Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, V.M.J.; Lloyd, C.A.; Rowe, K.J. The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaffield, S. Critical friendship, dialogue and learning, in the context of Leadership for Learning. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2008, 28, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, S.; Waniganayake, M.; De Nobile, J.J. Leading with intent: Cultivating community conversation to create shared understanding. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2016, 27, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozulin, A. (Ed.) Vygotsky’s Educational Theory in Cultural Context; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Cole, M., Ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Rocconi, L. The Impact of Learning Communities on First Year Students’ Growth and Development in College. Res. High. Educ. 2011, 52, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. Cognitive Development in Children: Piaget Development and Learning. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1964, 2, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausubel, D. Educational Psychology—A Cognitive View; Holt, Reinhart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, J.; Scott, P. Individual and sociocultural views of learning in science education. Sci. Educ. 2003, 12, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.L. How to Do Things with Words: The William James Lectures Delivered at Harward University in 1955, 2nd ed.; Harward University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hornscheidt, L.; Landqvist, M. Språk och Diskriminering [Language and Discrimination]; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini, D. Practice Theory, Work, and Organization—An Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kozulin, A. Sociocultural Contexts of Cognitive Theory. Hum. Dev. 1999, 42, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Hallinger, P. A Mirroring Process: From School Management Team Cooperation to Teacher Collaboration. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2018, 17, 238–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geijsel, F.P.; Krüger, M.L.; Sleegers, P.J.C. Data feedback for school improvement: The role of researchers and school leaders. Aust. Educ. Res. 2010, 37, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, J. Leadership for learning in the preschool: Preschool managers’ perspectives on strategies and actions in the systematic quality work. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2019, 47, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J.; Lauren Whitty, L. The role of tag questions in classroom discourse in promoting student engagement. Classr. Discourse 2022, 13, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalovich, A.; Netz, H. Tag-naxon? (Tag-right?) in Instructional Talk: Opening or Blocking Learning Opportunities. J. Pragmat. 2018, 137, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram-Tsabari, A.; Sethi, R.J.; Bry, L.; Yarden, A. Using questions sent to an Ask-A-Scientist site to identify children’s interests in science. Sci. Educ. 2006, 90, 1050–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.; Osborne, J. Students’ questions: A potential resource for teaching and learning science. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2008, 44, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, H. Learner Initiatives and Learning Opportunities in the Language Classroom. Classr. Discourse 2011, 2, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margutti, P.; Drew, P. Positive Evaluation of Student Answers in Classroom Instruction. Lang. Educ. 2014, 28, 436–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R. Summons Turns: The Business of Securing a Turn in Busy Classrooms. In International Perspectives on ELT Classroom Interaction; Seedhouse, P., Jenks, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 28–48. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, C.J.; Gilbert, F.S.; McGregor, P.K. Asking Questions in Biology: Design, Analysis and Presentation in Practical Work, 1st ed.; Longman: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lasagabaster, D.; Doiz, A. Classroom interaction in English-medium instruction: Are there differences between disciplines? Lang. Cult. Curric. 2023, 36, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Latham, D. Social Work in Public Libraries: A Survey of Heads of Public Library Administrative Units. J. Libr. Adm. 2021, 61, 758–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenijević, O.; Trivan, D.; Podbregar, I.; Šprajc, P. Strategic aspect of knowledge management. Organizacija 2017, 50, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wildemuth, B.M. Qualitative analysis of content. In Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science; Wildemuth, B.M., Ed.; Libraries Unlimited: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 318–329. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg, J.; Johnsson, A.; Granklint Enochson, P. Coming to Terms with Feedback from Critical Friends: Reflections of Risks in a Swedish Regional Collaboration Project. In Partnerships in Education: Risks in Transdisciplinary Educational Research; Otrel-Cass, K., Laing, K.J.C., Wolf, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Chapter 14; pp. 293–314. ISBN 978-3-030-98452-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supermane, S.; Mohd Tahir, L. An overview of knowledge management practice among teachers. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2018, 67, 616–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Research Council. Good Research Practice. 2017. Available online: https://www.vr.se/english/analysis/reports/our-reports/2017-08-31-good-research-practice.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).