Higher Education Fields of Study and the Use of Transferable Skills at Work: An Analysis Using Data from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) in Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source Data

2.2. Dependent Variable

2.3. Independent Variables

2.4. Method of Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

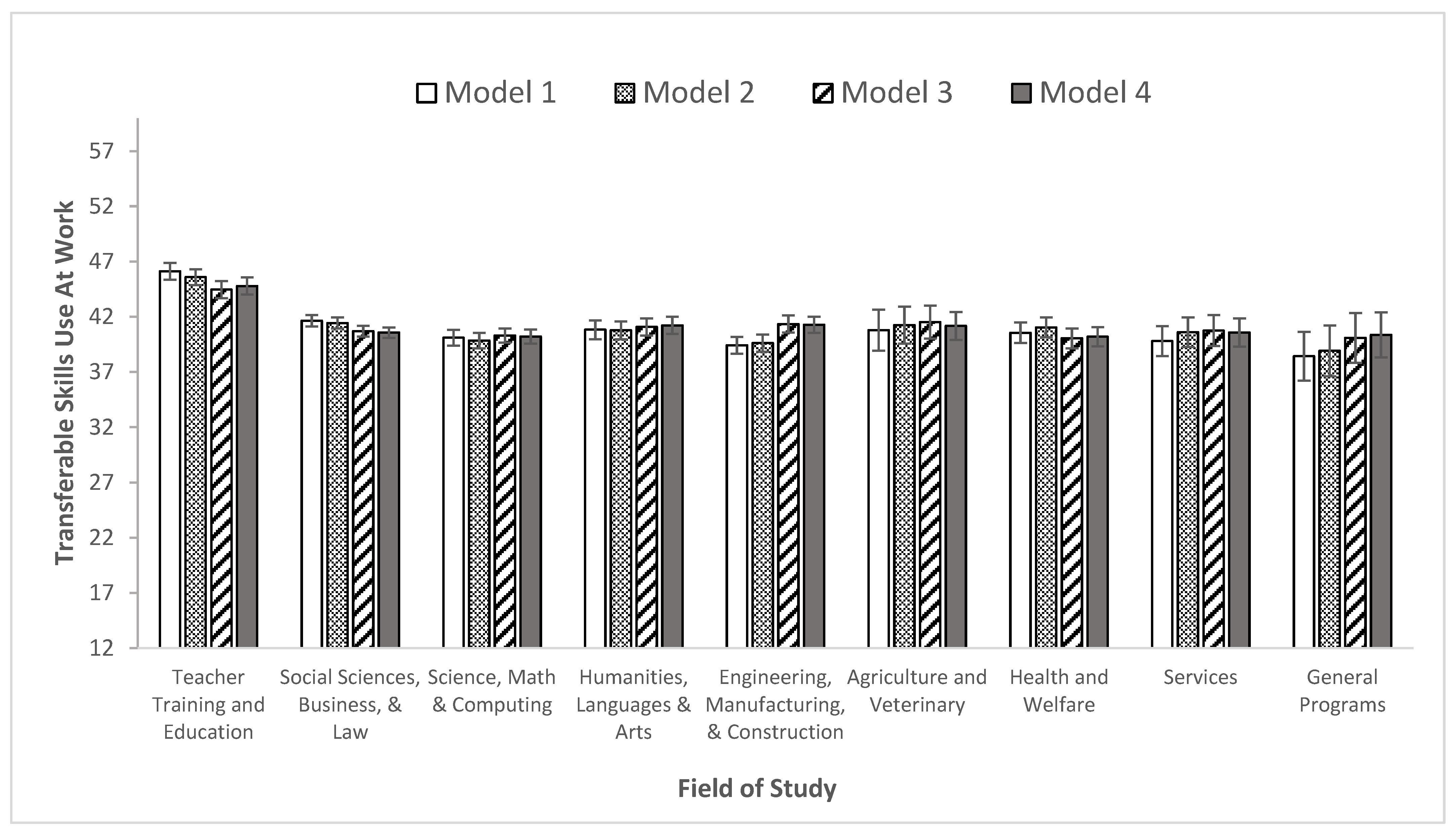

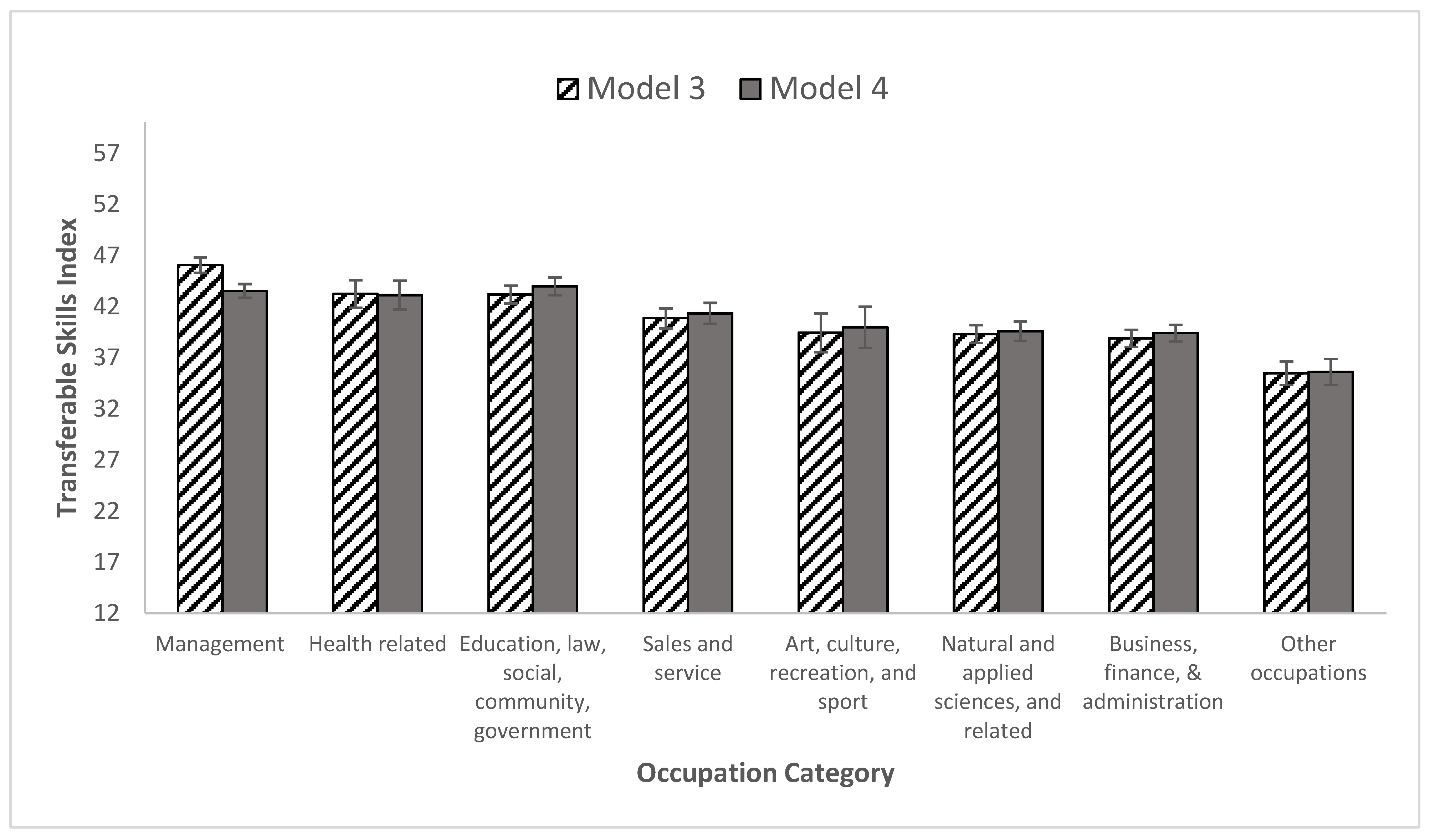

3.2. Regression Models

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, W.; Joseph, E. Aoun: Robot-Proof: Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. High Educ. 2019, 78, 1143–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, I.; Vamosi Zarandne, K. Digital Marketing Employability Skills in Job Advertisements—Must-Have Soft Skills for Entry Level Workers: A Content Analysis. Econ. Sociol. 2022, 15, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs: Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution; Global Challenge Insight Report; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kreber, C. The University and Its Disciplines: Teaching and Learning Within and beyond Disciplinary Boundaries; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-203-89259-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, J.; Hilton, M. (Eds.) Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-309-25649-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M.A.; Overton, T.; Kitson, R.R.; Thompson, C.D.; Brookes, R.H.; Coppo, P.; Bayley, L. ‘They Help Us Realise What We’re Actually Gaining’: The Impact on Undergraduates and Teaching Staff of Displaying Transferable Skills Badges. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2020, 23, 8023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R. Employers’ Demands for Personal Transferable Skills in Graduates: A Content Analysis of 1000 Job Advertisements and an Associated Empirical Study. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2002, 54, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarten, H.P. What Should Students Learn at University, and Are They Learning It? In Nothing Less than Great: Reforming Canada’s Universities; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021; ISBN 978-1-4875-0945-3. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Skills Outlook 2019: Thriving in a Digital World; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prinsley, R.; Baranyai, K. STEM Skills in the Workforce: What Do Employers Want? Occasional Paper Series; Australian Government, Office of the Chief Scientist: Canberra, Australia, 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Humans Wanted. How Canadian Youth Can Thrive in the Age of Disruption; Royal Bank of Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten, H.P.; Brumwell, S.; Chatoor, K.; Hudak, L. Measuring Essential Skills of Postsecondary Students: Final Report of the Essential Adult Skills Initiative; Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian University Survey Consortium. 2019 First Year Student Survey: Master Report; Canadian University Survey Consortium: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fenesi, B.; Sana, F. What is Your Degree Worth? The Relationship Between Post-Secondary Programs and Employment Outcomes. Can. J. High. Educ. 2015, 45, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business + Higher Education Roundtable. Empowering People for Recovery and Growth: 2022 Skills; Survey Report; Business Council of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.A. A Brief Introduction to Higher Education in Canada. In Higher Education in Canada; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-203-35771-2. [Google Scholar]

- Usher, A.; Balfour, J. The State of Postsecondary Education in Canada 2024; Higher Education Strategy Associates: Toronto, ON, USA, 2024; pp. 1–131. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Education. A Test of Leadership: Charting the Future of US Higher Education; US Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 1–62.

- National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education (Dearing Committee). Education in the Learning Society; Her Majesty’s Stationery Office: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Higher Education Council (Australia). Achieving Quality; Australian Government Public Service: Canberra, Australia, 1992; ISBN 0-644-25195-6. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Teaching and Learning: Towards a Learning Society; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1995; pp. 1–70.

- Advance HE. Framework for Embedding Employability in Higher Education. Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/framework-embedding-employability-higher-education-0 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- CivicAction. Now Hiring: The Skills That Companies Want That Young Canadians Need; CivicAction: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Express Employment Professionals. A Canadian Education Revolution, Aligning Classrooms and Careers: How the System Fails to Prepare Workers—And What Needs to Change; Express Services Inc.: Oklahoma City, OK, USA, 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ontario Promoting. Excellence: Ontario Implements Performance Based Funding for Postsecondary Institutions. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/59368/promoting-excellence-ontario-implements-performance-based-funding-for-postsecondary-institutions (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Peters, D. Performance-Based Funding Comes to the Canadian Postsecondary Sector. Univ. Aff. 2021, 22, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster University Development of the Experiential Learning Strategic Framework. Available online: https://provost.mcmaster.ca/teaching-learning/strategy/experiential-learning/strategic-framework/development/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Gregory, E.; Kanuka, H. Employability Skill Development: Faculty Members’ Perspectives in Non-Professional Programs. Can. J. Career Dev. 2022, 21, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Guppy, N. Fields of Study, College Selectivity, and Student Inequalities in Higher Education. Soc. Forces 1997, 75, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenette, M.; Frank, K. Earnings of Postsecondary Graduates by Detailed Field of Study; Economic Insights; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, R. Disciplinary Differences and University Teaching. Stud. High. Educ. 2001, 26, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylonen, A.; Gillespie, H.; Green, A. Disciplinary Differences and Other Variations in Assessment Cultures in Higher Education: Exploring Variability and Inconsistencies in One University in England. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, A.; Walters, D.; Howells, S. Employment and Wage Gaps Among Recent Canadian Male and Female Postsecondary Graduates. High Educ. Policy 2021, 34, 724–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenette, M. High School Academic Performance and Earnings by Postsecondary Field of Study; Economic and Social Reports; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Ye, X. Heterogeneous Major Preferences for Extrinsic Incentives: The Effects of Wage Information on the Gender Gap in STEM Major Choice. Res. High. Educ. 2021, 62, 1113–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, R.J. Arts Majors and the Great Recession: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Educational Choices and Employment Outcomes. J. Cult. Econ. 2021, 46, 635–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, D. The Relationship Between Postsecondary Education and Skill: Comparing Credentialism with Human Capital Theory. Can. J. High. Educ. 2004, 34, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Is Field of Study a Factor in the Earnings of Young Bachelor’s Degree Holders? Census in Brief; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016; p. 10.

- Li, G.; Long, S.; Simpson, M.E. Self-Perceived Gains in Critical Thinking and Communication Skills: Are There Disciplinary Differences? Res. High. Educ. 1999, 40, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, R. Postsecondary Education and Skills in Canada; Council of Ministers of Education, Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; ISBN 978-0-88987-237-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sinche, M.; Layton, R.L.; Brandt, P.D.; O’Connell, A.B.; Hall, J.D.; Freeman, A.M.; Harrell, J.R.; Cook, J.G.; Brennwald, P.J. An Evidence-Based Evaluation of Transferrable Skills and Job Satisfaction for Science PhDs. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambhir, M.; Broad, K.; Evans, M.; Gaskell, J. Characterizing Initial Teacher Education in Canada: Themes and Issues; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; Greenhill, J. Factors Shaping How Clinical Educators Use Their Educational Knowledge and Skills in the Clinical Workplace: A Qualitative Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law Society of Ontario Lawyer Licensing Process. Available online: https://lso.ca/becoming-licensed/lawyer-licensing-process#graduates-of-accredited-common-law-schools-who-will-acquire-an-nbsp-l-b-j-d-in-canada-4 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Billing, D. Teaching for Transfer of Core/Key Skills in Higher Education: Cognitive Skills. High Educ. 2007, 53, 483–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, I.; Nixon, I.; Wiltshire, J. Personal Transferable Skills in Higher Education: The Problems of Implementing Good Practice. Qual. Assur. Educ. 1998, 6, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMEC Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: http://www.piaac.ca/590/FAQ.html (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Statistics Canada. PIAAC 2012—Data Dictionary, Public Use Microdata File (PUMF); Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012; p. 222.

- Statistics Canada. The Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, 2012—User Guide, Public Use Microdata File (PUMF); Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013; pp. 1–127.

- Torres-Reyna, O. Getting Started in Factor Analysis (Using Stata 10); Princeton University: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, A.G.; Pearce, S. A Beginner’s Guide to Factor Analysis: Focusing on Exploratory Factor Analysis. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2013, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vaus, D.A. Surveys in Social Research, 6th ed.; Social Research Today; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-415-53015-6. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Manchini, N.; Jiménez, Ó.; Díaz, N.R. Teachers’ Soft Skills: A Scoping Review. PsyArXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağçam, R.; Doğan, A. A Study on The Soft Skills of Pre-Service Teachers. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2021, 17, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.A. A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning; Routledge Falmer: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-1-134-31091-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, D. Transferable Skills: A Philosophical Perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 1993, 18, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, I.; Haj Youssef, M.; Reinhardt, R. Higher Education Student Intentions behind Becoming an Entrepreneur. High. Educ. Ski. Work Based Learn. 2023, 14, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, P.; Simó, P.; Marco, J. Understanding STEM Career Choices: A Systematic Mapping. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Houston, M. Teaching as a Career Choice: The Motivations and Expectations of Students at One Scottish University. Educ. Stud. 2023, 49, 937–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, B.H.; Munthe, E.; Ross, S.A.; Hitt, L.; El Soufi, N. Who Becomes a Teacher and Why? Rev. Educ. 2022, 10, e3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wranik, W.D.; McPherson, M.; Caron, I.; Liu, H. Frontiers of Public Service Motivation Research in Canada: A Scoping Review. Can. Public Adm. 2024, 67, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. Learning a Role: Becoming a Nurse. In The Routledge International Handbook of Learning; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-429-23053-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen, L.; Turcotte, M. Persistent Overqualification Among Immigrants and Non-Immigrants; Insights on Canadian Society; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, D. Career Decision-Making of Immigrant Young People Who Are Doing Well: Helping and Hindering Factors; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N. A Literature Review on Career Chance Experiences: Conceptualization and Sociocultural Influences on Research. J. Employ. Couns. 2022, 59, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgen, W.; Buchanan, M.; Mathew, D.; Nishikawara, R. Career Transition of Immigrant Young People: Narratives of Success. Can. J. Couns. Psychother. 2021, 55, 158–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Krahn, H. Living through Our Children: Exploring the Education and Career ‘Choices’ of Racialized Immigrant Youth in Canada. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 16, 1000–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.A.; Lundberg, A.; Geerlings, L.R.C.; Bhati, A. Shifting Landscapes in Higher Education: A Case Study of Transferable Skills and a Networked Classroom in South-East Asia. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2019, 39, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.A.; Tamtik, M.; Trilokekar, R.D. Research on Higher Education in Canada: History, Emerging Themes and Future Directions. Peking Univ. Educ. Rev. 2020, 2, 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, R.C.; Shipper, F.M. The Impact of Managerial Skills on Employee Outcomes: A Cross Cultural Study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1414–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis and Inuit; National Houshold Survey; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011.

- Melvin, A. Postsecondary Educational Attainment and Labour Market Outcomes Among Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Findings from the 2021 Census; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, P.M. A Comparison of Cooperative Education Graduates with Two Cohorts of Regular Graduates: Fellow Entrants and Fellow Graduates. J. Coop. Educ. 1992, 27, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, D. “Recycling”: The Economic Implications of Obtaining Additional Post-Secondary Credentials at Lower or Equivalent Levels*. Can. Rev. Sociol. Rev. Can. De Sociol. 2008, 40, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.; Mishra, C.E.B.; Doherty, E.; Nelson, J.; Duncan, E.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Hodgins, K.; Mactaggart, W.; Gillis, D. Transdisciplinary, Community-Engaged Pedagogy for Undergraduate and Graduate Student Engagement in Challenging Times. Int. J. High. Educ. 2021, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categorical Independent Variables | Percentages | |

|---|---|---|

| Field of Study—Highest Level Education | ||

| Teacher Training and Education | 11.28 | |

| Social Sciences, Business, & Law | 26.18 | |

| Science, Math and Computing | 14.32 | |

| Humanities, Languages and Arts | 9.47 | |

| Engineering, Manufacturing, and Construction | 17.02 | |

| Agriculture and Veterinary | 1.55 | |

| Health and Welfare | 12.02 | |

| Services | 4.81 | |

| General Programs | 3.34 | |

| Occupation Category (NOC System) | ||

| Management | 14.27 | |

| Health related | 9.24 | |

| Education, law, social, community, government | 20.64 | |

| Sales and service | 12.07 | |

| Art, culture, recreation, and sport | 2.87 | |

| Natural and applied sciences, and related | 13.08 | |

| Business, finance, and administration | 16.82 | |

| Other Occupations | 11.02 | |

| Manage Other Employees | ||

| Yes | 35.32 | |

| No | 64.68 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 49.34 | |

| Female | 50.66 | |

| Country of Birth | ||

| Born in Canada | 69.46 | |

| Not Born in Canada | 30.54 | |

| Location of Higher Education Program | ||

| Canada | 80.13 | |

| North America & Western Europe | 5.39 | |

| All Other Regions | 14.48 | |

| Indigenous | ||

| Yes | 1.88 | |

| No | 98.12 | |

| Disability/Long-term Illness | ||

| Yes | 26.32 | |

| No | 73.68 | |

| Language of the Survey | ||

| English | 79.69 | |

| French | 20.31 | |

| Quantitative & Continuous Variables | Mean | Median | Mode | Std Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |||||||

| Transferable Skills Index | 41.14 | 42 | 45 | 9.77 | 12 | 45 | |

| Independent Variables | |||||||

| Years of Fulltime Work in Lifetime | 17.73 | 16 | 10 | 10.68 | 0 | 40 | |

| Years of Formal Education | 15.48 | 16 | 14 | 1.63 | 14 | 22 | |

| Age | 40–44 | 30–34 | 25 | 65 | |||

| Transferable Skill Use at Work | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | Std. Err. | Sig | b | Std. Err. | Sig | b | Std. Err. | Sig | b | Std. Err. | Sig | ||

| Field of Study—Highest Level Education | |||||||||||||

| Teacher Training and Education | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Social Sciences, Business, & Law | −4.480 | 0.555 | *** | −4.151 | 0.522 | *** | −3.755 | 0.559 | *** | −4.216 | 0.549 | *** | |

| Science, Math, and Computing | −6.014 | 0.626 | *** | −5.735 | 0.615 | *** | −4.157 | 0.660 | *** | −4.575 | 0.647 | *** | |

| Humanities, Languages and Arts | −5.289 | 0.665 | *** | −4.808 | 0.629 | *** | −3.384 | 0.656 | *** | −3.564 | 0.661 | *** | |

| Engineering, Manufacturing, and Construction | −6.701 | 0.655 | *** | −5.967 | 0.684 | *** | −3.115 | 0.741 | *** | −3.515 | 0.707 | *** | |

| Agriculture and Veterinary | −5.329 | 1.308 | *** | −4.336 | 1.274 | ** | −2.938 | 1.031 | ** | −3.608 | 0.916 | *** | |

| Health and Welfare | −5.568 | 0.726 | *** | −4.545 | 0.687 | *** | −4.409 | 0.825 | *** | −4.596 | 0.817 | *** | |

| Services | −6.324 | 1.009 | *** | −4.981 | 0.991 | *** | −3.710 | 1.046 | *** | −4.214 | 0.990 | *** | |

| General Programs | −7.692 | 1.336 | *** | −6.666 | 1.364 | *** | −4.375 | 1.333 | ** | −4.426 | 1.213 | *** | |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Male | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Female | −1.463 | 0.379 | *** | −1.283 | 0.375 | ** | −1.124 | 0.361 | ** | ||||

| Country of Birth | |||||||||||||

| Born in Canada | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Not Born in Canada | −1.355 | 0.557 | * | −0.300 | 0.539 | n.s. | −0.330 | 0.509 | n.s. | ||||

| Location of Higher Education | |||||||||||||

| Canada | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| N. America & Western Europe | −0.167 | 0.826 | n.s. | −0.363 | 0.765 | n.s. | −0.222 | 0.749 | n.s. | ||||

| All Other Regions | −4.778 | 0.682 | *** | −4.207 | 0.655 | *** | −3.741 | 0.623 | *** | ||||

| Indigenous | |||||||||||||

| Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| No | 0.618 | 0.704 | n.s. | 0.149 | 0.735 | n.s. | 0.207 | 0.699 | n.s. | ||||

| Disability or Long-term Illness | |||||||||||||

| Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| No | −0.167 | 0.406 | n.s. | −0.279 | 0.382 | n.s. | −0.325 | 0.368 | n.s. | ||||

| Language of Survey | |||||||||||||

| English | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| French | −1.883 | 0.345 | *** | −1.567 | 0.327 | *** | −1.433 | 0.321 | *** | ||||

| Years of Higher Education | |||||||||||||

| 0.957 | 0.103 | *** | 0.699 | 0.105 | *** | 0.533 | 0.104 | *** | |||||

| Age | |||||||||||||

| 0.131 | 0.087 | n.s. | −0.848 | 0.155 | *** | −0.837 | 0.148 | *** | |||||

| Years of Fulltime Work in Lifetime | |||||||||||||

| 0.211 | 0.031 | *** | 0.191 | 0.030 | *** | ||||||||

| Occupation Category (NOC System) | |||||||||||||

| Management | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||||

| Health related | −2.828 | 0.834 | ** | −0.406 | 0.813 | n.s. | |||||||

| Education, law, social, community, government | −2.888 | 0.552 | *** | 0.459 | 0.579 | n.s. | |||||||

| Sales and service | −5.210 | 0.631 | *** | −2.181 | 0.639 | ** | |||||||

| Art, culture, recreation, and sport | −6.637 | 1.078 | *** | −3.557 | 1.035 | ** | |||||||

| Natural and applied sciences, and related | −6.762 | 0.589 | *** | −3.924 | 0.591 | *** | |||||||

| Business, finance, & administration | −7.172 | 0.536 | *** | −4.115 | 0.564 | *** | |||||||

| Other occupations | −10.585 | 0.737 | *** | −7.919 | 0.700 | *** | |||||||

| Manage Other Employees | |||||||||||||

| Yes | - | - | - | ||||||||||

| No | −5.892 | 0.354 | *** | ||||||||||

| * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 | R2 = 0.041 | R2 = 0.111 | R2 = 0.206 | R2 = 0.273 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mishra, C.E.B.; Walters, D.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Gillis, D.; Jacobs, S. Higher Education Fields of Study and the Use of Transferable Skills at Work: An Analysis Using Data from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) in Canada. Trends High. Educ. 2025, 4, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4020019

Mishra CEB, Walters D, Fraser EDG, Gillis D, Jacobs S. Higher Education Fields of Study and the Use of Transferable Skills at Work: An Analysis Using Data from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) in Canada. Trends in Higher Education. 2025; 4(2):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4020019

Chicago/Turabian StyleMishra, Christine E. B., David Walters, Evan D. G. Fraser, Daniel Gillis, and Shoshanah Jacobs. 2025. "Higher Education Fields of Study and the Use of Transferable Skills at Work: An Analysis Using Data from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) in Canada" Trends in Higher Education 4, no. 2: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4020019

APA StyleMishra, C. E. B., Walters, D., Fraser, E. D. G., Gillis, D., & Jacobs, S. (2025). Higher Education Fields of Study and the Use of Transferable Skills at Work: An Analysis Using Data from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) in Canada. Trends in Higher Education, 4(2), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu4020019