Abstract

This paper contributes to international debates about ‘authenticity’ in higher education, especially where this is embroiled in technology-oriented aspects of educational policy and practice. It describes activity theoretical research in a setting of engineering higher education, in industrial attachments taking place at distance, during which students and lecturers experience problems with technology-mediated interactions. Prior to the research-intervention that we describe in the paper, these interactions had been implemented through top-down policy, with work-related practices being conducted in the name of authenticity—a notion used in framing education as preparing students for economic work, in which digital technologies are increasingly embroiled. We describe an activity theoretical approach, and an online Change Laboratory methodology, through which students and lecturers envision and enact change to these practices. Their activity is thus reconfigured through their confrontation and renegotiation of authenticity. Our core contribution is to illustrate, through exposing and aggravating contradictions in technology-mediated activity, how practice in higher education can be considered authentic in and of itself, as distinct from solely having authenticity in preparing students for economic work.

1. Introduction

As researchers and scholars of technology-enhanced learning (TEL) practice and of higher education (HE), we recognise the notion of authenticity being increasingly deployed as an educational ideal, with authenticity increasingly providing a focus for research and scholarship on technological mediation in HE. We seek to make a contribution to current international debates, specifically regarding how authenticity is embroiled in technology-oriented aspects of educational policy and practice. Authenticity has been repositioned in recent years, from its early denoting of critical, intellectual, and social engagement with the world [1], to increasingly signifying the extent to which learning environments and practices prepare students for economic work [2,3,4]. Educational technologies—particularly digital technologies—have long been implicated in the pursuit of authenticity, with commentators too often referring to authentic TEL in oversimplistic ways: “Technology based education has long been felt … to chime with Vygotskian notions of ‘authentic’ learning where knowledge is constructed actively by learners …” [5] (p. 14).

Authenticity has a paradoxical status in social life and in HE. Some philosophical schools regard the notion of authenticity as undeserving of the attention of educational researchers, since social beings are always themselves, while others place importance on the authentication of those around us, through the “alignment of inner state and outer conduct” [2] (p. 32). In our current paper we examine material environments of work and learning, where normative technologies, policies, and power structures inevitably influence authenticity in learning, and where authenticity relies on the accounts of others. Authentic HE is notably dilemmatic in educational policy and practice for particular professions, such as engineering, whose raison d’être is often understood as preparing students for distinct career paths [2]. Students and lecturers face tensions of normativity in their attempts to provide technology-mediated, authentic, educational experiences for the so-called professions: on the one hand, authentic TEL interactions are expected to encourage and develop HE students’ reflexivity, legitimising their critique of educational and professional practice; on the other, there is an interminably closer alignment of education with industry, enjoying “near-universal endorsement” [6] (p. 108), which generates work-related expectations and has concomitant influences on the selection and use of technologies in educational practice. Claimed benefits of authentic HE include:

- Furthering integration of work and learning for prospective graduates, dismantling “barriers between the two bodies marked by the hand-off which occurs after graduation” [7] (p. 61);

- Offering vocationally oriented learning with “real-world relevance”, contrasting with “enculturation into the practices of universities and classrooms” [3] (p. 5);

- Economic furtherance of education, “crucial to business competitiveness, prosperity and fairness” [8] (p. 592).

To examine these issues, in our current paper we introduce and analyse an expansive research-intervention, conducted in the setting of a vocationally oriented, part-time, small and specialist, higher education (HE) programme in engineering, at a public university in the United Kingdom (UK) which is overtly seeking to deepen its established strategic relationships with industry. We describe a practice setting, where industrial attachments in professional HE—often termed the capstone projects of degrees—are conducted at distance, toward the concluding period of engineering HE programmes. During these attachments, work-related digital technologies and related teaching–learning interactions have previously been implemented, through managerial top-down endeavours, in the name of authenticity. A group of six learners and two lecturers found these technologies and practices to be sub-optimal, provoking the research-intervention that we describe. We examine the experiences of lecturers and students, tracing their dissatisfaction, renegotiation, and redesign of authentic technology-mediated interactions. Doing so provides useful insights into how these lecturers and students confronted issues of authenticity themselves.

An original intent of our research-intervention was to assist participants to reconfigure educational technologies: laptops, smartphones, and virtual learning environments. These serve to mediate their interactions with each other and with managers during industrial attachments. Yet participants did not restrict their work to this focus. We describe how, stimulated by their perceived need to redesign mediating technologies, they instead called upon expansive acts, turning as the intervention unfolded to alternatively direct their attention and social negotiation toward authenticity itself, critiquing its implications for their envisioning and enactment of change to technology-mediated interactions. Our current paper’s core argument is that our analyses of the research-intervention’s unfolding shows that HE is authentic—in and of itself—as distinct from only being speculatively authentic, in its state as a precursor to, and preparation for, economic work.

We describe in subsequent sections how an activity theoretical approach, and an online version of the Change Laboratory methodology [9], empowered these participants to question and renegotiate the qualitative meaning of authenticity in their activity, informing their redesign of technology-mediated interactions. In the social circumstances we describe, managerialist forms of authenticity—as essentialist workplace readiness—had resulted in repressive, workplace-oriented, technology-mediated interactions, which students and their lecturers felt the need to confront and reject. Our paper’s findings illustrate how students and lecturers were fortified by their socially renegotiated conceptions of authenticity—they found a shared sense of legitimacy as learners, rather than as workers-in-waiting—which they collaboratively developed through expansive change.

Our deeply contextualised analyses describe how participants identified, exposed, and aggravated their activity’s primary contradictions—capitalist tensions between societal benefit, and exchange in a transaction for a commodity (cf. Foot [10]). We describe in this paper how we engendered and analysed expansive processes [11], coupling our analyses of the activity’s contradictions with Rabardel’s [12] theory of instrumental genesis, whereby problematic circumstances can be met by people appropriating and adapting their available technologies (known as instrumentalisation), and by developing their own abilities at using those technologies (known as instrumentation). Our paper’s analyses and findings illustrate an interplay of design-for-use and design-in-use [13], as these students and lecturers redesigned technology-mediated interactions to suit their own contested notions of authenticity. In this current paper we ask the research question:

How does our understanding of ‘authenticity’ in HE’s technology-mediated interactions benefit from the analysis of primary contradictions, and instrumental genesis, undertaken during a Change Laboratory research-intervention in engineering education?

We aspire to contribute to a burgeoning body of critical scholarship, which rejects the notion of authenticity flourishing, unchallenged, in its influence on education. We will not claim to present an exemplar of redesigned technology-mediated interactions, nor will we claim widespread generalisability for a plethora of educational settings and practices. Rather, we analyse expansive acts from one research-intervention, examining change processes through which the redesign of ‘authentic’ TEL practice was envisioned and enacted by participants. We show how we learned, through our Change Laboratory methodology’s techniques and our analyses of the interplay of contradictions and instrumental genesis in technology-mediated interactions, that authenticity ought not to be considered as solely an attribute for preparing economic workers. Instead, authenticity ought to be examined and developed, by students and lecturers, as a qualitatively meaningful feature of education itself, nurtured in their learning processes.

We firstly summarise particular sections of the literature to position our contribution against the backdrop of scholarship. We then set out our paper’s activity theoretical framework [11], including a focus on instrumental genesis [12] and our instantiation of expansive learning using the Change Laboratory methodology [9], whereby we analyse how participants identified the potential of their activity, together exploring its zone of proximal development. In the findings, we set out how participants exposed and aggravated primary contradictions in our online workshops, alongside examples of enacted instrumental genesis. To close our paper, we speculate on implications for colleagues researching authenticity in TEL practice, and for educational policymakers who make decisions in the name of authenticity.

2. Literature Review

The literature review positions our current paper amongst a backdrop of scholarship in HE, where authenticity is a prevalent and contested notion, often invoked in the study of the relevance, legitimacy, and value of educational practice. We structure our review around three conceptual distinctions of authenticity in HE that are common in this literature, which we believe to have particular implications for the practice setting and problems.

One strand is centred around authenticity as a euphemism for workplace acculturation, accustoming students to managerialist interactions of work, in ways “loaded with almost oppressive normative implications” [2] (p. 31). A second body of related work juxtaposes workplace practice with HE policy, where work is presented as real-worldly, and policy reforms are a necessary part of environmental control, to persuade students “to perceive learning environments as both authentic and pedagogically appropriate … or at least to suspend disbelief” [14] (p. 68). A third strand has its focus on commodification, where authenticity is positioned as a means of marketising HE—perversely eroding less profitable programmes—jeopardising authenticity’s “potential to promote educationally meaningful learning experiences for all involved” [15] (p. 1137). We position our paper’s contribution at a juncture of these three thematic strands, each discussed in turn below using a consistent structure in which we address common perspectives and drivers, notable counter-perspectives, and the implications for our current paper.

2.1. Authenticity as Preparing HE Students for Future Employment

In one body of scholarship, authenticity is presented as a driver for closer economic alignment between HE and work, a perspective long-established and prevalent in fields such as hard sciences, law, engineering, and medicine [2]. This view positions authentic education as delivering workers ready for a neoliberal economy: “tasks students do, reflect tasks seen in real professions and workplaces” [3] (p. 2). In confronting ambiguity and inconsistencies of authentic education, Sarid’s [4] work—which otherwise promotes the idea of autonomy and social identity—describes authentic education as “connecting learning to real problems … to life beyond the classroom” (p. 475, our emphases). In this way, ‘real life’—a euphemism for the world of work—serves HE’s business model: people study for work in the economy; their return on investment is reported through post-study earnings; and the earnings ratio is re-presented as evidence of authentic education, with institutions “competing for students as customers” [16] (p. 66).

For us, this is a worrying trend which is often left unquestioned. We find a burgeoning body of researchers who directly confront economic advantage as a measure of authenticity, and who challenge students to do so. Stromholt and Bell [17] promote science students to critique authenticity, to see themselves as producers of emancipatory knowledge, and to critique authentic endeavours “… as a productive way to address and dismantle dominant discourses and power structures associated with neoliberalism” (p. 3). With student clinicians, Morris et al. [18] challenge participants “to reflect critically on historic practices and the ways things are done around here” (p. 40) as they undertake changes to authentic setting for learning clinical practice. Authentic assessment is confronted by McArthur [19], who holds concerns for authenticity becoming an educational buzzword, describing a conflation of “authentic assessment … as assessment linked to real-world tasks, the world of work” (p. 86) noting that shallow conceptions of authenticity result in missed opportunities to challenge institutional norms. Critical studies in this body of literature thus reject authenticity as the furtherance of economic alignment with work, as does our own research.

In our current paper we counter the conflation of authenticity in HE with work-readiness, and we examine data generated by empowering participants to confront such notions expansively, collaboratively, and antagonistically. Our paper’s intentions concur with Flavin’s [20] description of expansive learning, commencing with “dissent, the critical interrogation of established and accepted practice” (p. 72).

2.2. Authenticity in HE as an Impetus for Policy Reform

In a second strand of literature, increasing demand for authenticity in HE is invoked when stressing shortfalls of policy: unreformed educational policy, particularly at a meso-level, is framed as a barrier to innovation, and thus obstructive to authentic practice. Bozalek et al. [21] discuss how policy shortfalls contribute to the stultification of innovative technologies, the authors seeking “a way to bring the necessary complexity into learning to deal with challenges in professional practice after graduation” (p. 629). They describe frustrations with a policy disjuncture, between de-contextualised curricula and professional work: “while some elements of authentic learning can readily be instantiated … it could take a change in institutional culture and policy to facilitate other elements” (p. 637). In a similar call for educational reforms to bridge school policy with authentic practice, Rozario and Ortlieb [22] present tensions for teacher educators, seeking to introduce digital video technologies. The authors’ findings assist educational strategists “to understand and resolve the greater needs of education … provide connections to the many wider issues of the outside world.” (p. 303).

In a more critical flank of this strand of literature, scholars challenge claims that policy reforms per se lead to authentic practice. Forkosh-Baruch et al. [23] reverse the often-trite conception of a lead–lag relationship between strategic policy and operational practice, recognising complexities of accessing evidence in the daily reality of education, with teachers’ authentic practice being key to their confidence and influence of “evidence-based decisions regarding policy and practice” (p. 2220). Similarly, Clifford’s [24] work confronts “unilateral canonical policies” empowering people to “produce relational, democratic, practical, and meaningful institutional educational technology policies reflective of authentic realities” (p. 24). Cautioning of the extrapolation of policy devoid of context, Fürstenau et al. [25] warn against “policy-borrowing” (p. 453), noting that authentic practice observed in one context—in their study, Germany’s dual education system—cannot be replicated elsewhere merely by emulating policy.

These latter studies depict a body of researchers rejecting the unhelpful assumption that detached educational policy—merely in need of some reform by strategists—is a recipe to provoking authentic practice. We aspire to position our paper among these critical works: recognising policy as problematic, we nonetheless reject a dualism of inauthentic policy and authentic practice. We document the facilitation of social circumstances, in which participants—as the collaborative subject of the activity—come together to develop their own authentic education, influencing bottom-up policy themselves, engaging in ways which are “historical reality rather than an outcome of designed policy” (cf. Engeström and Sannino [26]).

2.3. Authenticity in HE as Exposing Students to Complex Problem Scenarios

In a third grouping of related literature, authenticity is used to explain social presence and engagement within HE, encouraging students’ intersubjectivity and their navigation of complexity. Authentic learning thus describes relational engagement, through complex problem scenarios and intersubjective tasks, which are “more than superficial experiments in co-creation” [16] (p. 18). There is a concomitant focus on negotiating participation, developing students’ abilities to make and honour commitments, without which “the character-self cannot be accepted as an authentic social being” [27] (p. 113).

The inference from much of this body of work is that complex learning scenarios are authentic if they necessitate diverse vocational collaborations, abstruse problem identification, and partiality of solutions. We find this somewhat problematic—yet only in the presumed inevitability of social complexity being related to economic work. Our pragmatic concern is that education becomes suited to ‘extant’ workplace scenarios, at the expense of critical engagement in ‘future’ complex challenges for humanity: this presents a dialectic of workplace readiness for authentic education, where “transferable skills are more valued than specific skills by prospective employers” [28] (p. 84), yet academics are valued for “degrees of authenticity and relevance … students’ perceptions of the teacher’s ‘professional’ currency and familiarity …” (p. 87).

In a critical turn, we find scholars who share the importance of authentic social complexity, yet who are not confined to vocational relevance, those who recognise that educational sites and settings are rich sources of their own complexities, which provide lucrative loci for authenticity and dilemmatic social conditions: Hagvall Svensson et al. [14], for example, discover that their authentic scenarios are a “double edged sword … increasing the legitimacy of the learning environment while simultaneously closing down opportunities for critical thinking” (p. 73). The growing embodiment of technology is implicated in these complex and authentic educational scenarios, “challenging HE programmes to decide how to prepare students for both working life and a social presence with ethical dilemmas that arise” [29] (p. 13).

We position our paper among these latter contributions, where merely ‘mimicking’ complexities of work, devoid of social context, with oversimplistic scenarios, will be unlikely to result in authentic learning. Commenting on the allure of simplicity, Kezar [30] notes that genuine epistemic development is more likely to be sustained by “change agents who use more complex approaches” (p. xv). We show in our paper how educational practice, and concomitant social interactions, are genuinely complex and authentic on their own terms, rather than emulating the complexities of waged labour.

2.4. Positioning This Paper Against the Backdrop of Scholarship in HE

Our literature review has positioned our paper at a nexus of scholarship that confronts and rejects authenticity as vocational readiness, in need of further top-down policy, deserving closer alignment with the social complexities of work. We find scholars who, like us, confront such notions of authenticity, navigating “various and at times opposing understandings of the very aims of authentic education” [4] (p. 474). We share their interests in pursuing genuine epistemic approaches to authenticity, recognising its complexity and need for social commitment, beyond a dualism with top-down policy, distanced from the transaction of waged labour. We do not see our contribution as readily generalisable: rather we seek to offer an unfolding account of people redesigning their own authentic TEL activity. We examine the instrumental role played by contested notions of authenticity in TEL, generating endeavours to design and redesign technology-mediated interactions, in contrast with authenticity as “a vague and superficial attribute that can hardly be useful in building a theoretical foundation for computer-supported collaborative learning” [31] (p. 105).

3. Theoretical Framework

To examine how and why people relate authenticity to technology-mediated interactions, we designed theoretical arrangements to examine technology mediation, social negotiation, antagonism, and collective socio-material change. We describe below our use of a theoretical framework, used across the remainder of our paper, which draws upon post-Vygotskyan activity theoretical principles. In examining disputed conceptions of authenticity, we provoked and analysed how people collectively envisioned and enacted change to their technology-mediated social activity, following the unfolding of a research-intervention using principles of Engeström’s [11] cultural and historical activity theory (CHAT). In our current paper we examine how learners and their lecturers changed their authentic technology-mediated interactions. We review their collaborative examination of their activity’s primary contradictions: tensions between use value (for application in direct social benefit) and exchange value (worth if exchanged for something else, usually monetary) as sources of change and development [10]. We use Rabardel’s [12] theory of instrumental genesis to investigate the interplay of instrumentalisation (appropriation and adaptation of technological instruments) and instrumentation (the development of skills and abilities). To structure and theorise change and development, we use expansive learning [11].

3.1. Cultural and Historical Activity Theory (CHAT)

Engeström’s [11] version of CHAT represents activity as a cultural, historical activity system where a collective subject (the group of people directly involved in activity) is oriented to an object (the material purpose and social motive of activity). This subject–object relationship is mediated by artefacts (tools acting on the world, and signs acting on the mind) which become instruments in use. The notion of artefact-mediated production makes CHAT particularly useful in change and innovation in TEL practice [20,32].

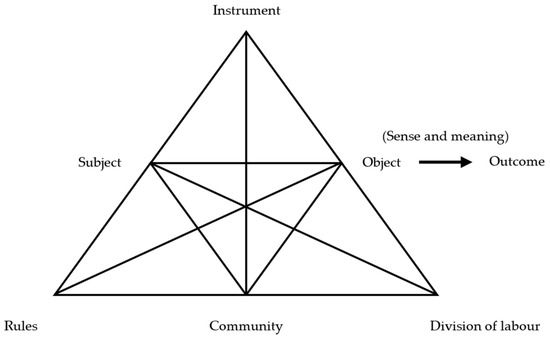

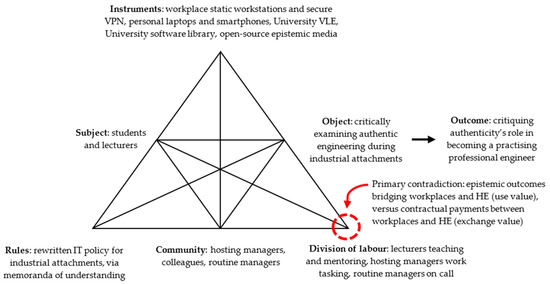

A graphical activity system illustrates elements and their interactions, with activity’s important yet less visible social mediators: rules, which regulate activity, formally and informally; community, the people beyond the subject, who have interest and influence in activity; and division of labour, describing how activity’s roles and rewards are distributed amongst the social group. The triangular representation of activity is shown in Figure 1, adapted from Engeström [11] (p. 78). Far from displaying a passive graphical model of a social system, an activity system is useful in interventionist research—such as that we draw on in our paper—to envision, enact, and consolidate purposeful change in work and learning activity. In the research-intervention which we examine in this paper, the model of activity and its contradictions was used actively and antagonistically, to attribute blame, and to expose and examine failure, informing change to “integrated, multilevel accounts of purposeful human activities” [33] (p. 85).

Figure 1.

Adaptation of Engeström’s [11] triangular activity system.

3.2. Contradictions in Activity

The identification, exposure, and aggravation of activity’s contradictions is a critical endeavour for sustained development; these contradictions are systemic tensions between or within elements of activity, indicating the potential for change [10]. Contradictions are important drivers of development and change, yet they are seldom exhibited directly, necessitating theoretical arrangements for their exposure and aggravation [34]. When participants expose and aggravate contradictions, they engage directly with the “mechanisms to help activity systems expand and transform … signalling the need for adaptation in the system” [35] (p. 97). Our paper focuses on one particular form—primary contradictions—as a continual tension of capitalist economics, with implications for change and development of social activity. Change to activity can be sustained when “the integrative concept of activity resolves, in one way or other, the contradictory demands of exchangeable commodities (exchange value), on one hand, and as functional elements in a system (use value), on the other hand” [36] (p. 277).

3.3. Instrumental Genesis

Instrumental genesis [12] can be described as a hybrid theory, with roots in activity theoretical approaches and also in French ergonomics. Two interrelated processes are involved in a fundamental dual movement of instrumental genesis: from subject-to-artefact, and from artefact-to-subject. The first is instrumentalisation, in which people modify a mediating technological artefact to better suit the object of their activity. The second is instrumentation, in which people develop their own skills and abilities to use their mediating technological artefact more effectively in their activity.

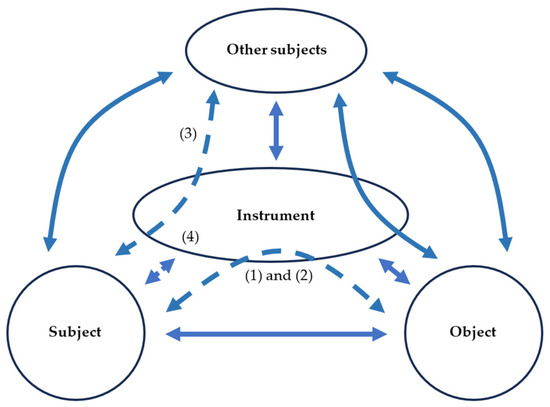

Artefacts become instruments through their use, in ways which can be more-or-less foreseen before being put to such use: “The artefact may be perceived as a hammer given its physical properties, but only when used for hammering does the artefact become a ‘hammer’ instrument. In other situations, the artefact may be a ‘weapon’ or a ‘bottle opener’ instrument” [37] (p. 321). These situational implications of mediation differentiate an artefact’s design-for-use (usually by its designers), and as artefact’s design-in-use (usually by its users) [13]. Four types of instrument mediation, shown by the dashed lines in Figure 2, are proposed in a typology by Lonchamp [38] and are of particular relevance to our current paper:

- Epistemic subject-object mediation (labelled (1) in Figure 2): directed towards epistemic understanding of the object and its evolution;

- Pragmatic subject-object mediation (2): directed toward transforming the object of activity and attaining results, noting that there is also a collaborative dimension to the mediation between other subjects and the object;

- Interpersonal mediation (3): directed from a subject toward other subjects, to know them or to act upon them;

- Reflexive mediation (4): directed back toward the originating subject.

Figure 2.

Adaptation of Lonchamp’s [38] typology of mediation in instrumented activity.

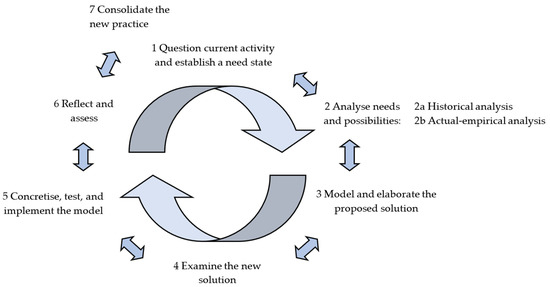

3.4. Expansivity

Expansive learning contrasts with predetermined “ready-made formats” of learning [31] (p. 96). The theory of expansivity acknowledges ambiguity and partiality of social practice, embracing contextual and epistemic diversity, and rejecting the pretence of consensus in change to work and learning. A simplified cycle of expansive learning is shown in Figure 3, adapted from Engeström [11] (p. 321). Such cycles typically have recursive and iterative sub-cycles, which are not shown in the image. Seven ideal-typical acts have been recognised by Engeström and a succession of activity theorists:

- Questioning, involving criticism or rejection of accepted practice, managerial plans, and established wisdom;

- Historical and empirical analysis, two related analytical actions, investigating the historical reasons and causes for the present situation, then identifying explanations of the existing order through the inner systemic relationships of activity;

- Modelling, whereby participants construct simplified, explicit, and observable media to explain the current situation and offer potential solutions;

- Examining, by applying the model in practice, to understand its dynamics, potential, and limitations;

- Implementing, where the model is enriched by being applied and conceptually extended;

- Reflecting, to evaluate the process of expansive learning, generating critique and further requirements;

- Consolidating, whereby participants embed outcomes into a new stable practice.

Success is accompanied by participants’ conscious reimagination of activity, with evidence that their object has been expanded, rather than merely reflected upon or passively discussed (examples from HE are examined by Bligh and Flood [39]).

Figure 3.

Expansive learning acts, from Engeström’s expansive cycle [11] (p. 321).

4. Research Design

In the research-intervention we analyse, our methodological arrangements sought to facilitate an expansive cycle. In the current paper we focus relatively narrowly on particular expansive turning points, while examining instrumental genesis, primary contradictions, and the participants’ redesign of their activity. In the research-intervention, we used a Change Laboratory methodology [9]. Change Laboratorians directly attempt to foster expansive learning, empowering participants in the design, conduct and analysis of a locally meaningful and expansive research-intervention in ways which are established and suited to HE [39]. The methodology aligned with our participants’ problematic social circumstances, assisting with the design, conduct, and analysis of activity theoretical tasks which prioritise technology mediation, historicity, and multi-voiced social interactions.

We provided participants with relatively structured—yet agile and variable—tasks and stimuli, which were designed to align expansive acts with the problematic circumstances described in the opening to our paper. We designed, conducted, and analysed nine online workshops, approximately weekly, to collaboratively and expansively identify and confront failure, facilitating participants in their exposure and aggravation of contradictions (see e.g., Engeström’s [31] background to the methodology). In these workshops, we presented ethnographic data, double stimulation tasks, and opportunities for problematisation and change. Participants collectively and expansively explored their activity’s zone of proximal development, promoting “learning that penetrates and grasps the pressing issues that humankind is facing today and tomorrow” [26] (p. 21). In practical terms, participants came together to propose, enact, and reflect on changes to their authentic activity, to recognise “past and currently conceived problems, arriving at a new vision of those problems and their solution, modelling and planning for future action” [40] (p. 494).

Our use of the Change Laboratory methodology provided us with means to engender and study these interactions, through a research-intervention enabling “participants to have an expanded awareness not only of themselves but also of their social milieu as a consequence of taking part in the research.” [41] (p. 44).

4.1. Research Site

Our research-intervention was conducted online, as was our own collaboration in its design and analysis. Lecturers were sited at the University during our workshops, although they physically travelled to the sites of the industrial attachments, approximately fortnightly, for scheduled visits. During the research, students themselves were physically located at hosting organisations of their industrial attachments: they chose to schedule our workshops during their time with hosts, which they deemed representative of typical future working arrangements.

While our research-intervention was conducted online, students were located at their sites of industrial attachments, allowing them to access evidence of experiences and observations. The sites were originally selected by course leaders at the institution, with the intention of consolidating advanced theory, while relating learning to professional practice: developing self-direction and confidence through reflexive, authentic tasks; collaborating with diverse groups and individuals in progressively challenging conditions; critically reflecting on knowledge, and negotiating its meaning for contemporary problems facing engineers and society; and developing students’ own work and learning support networks.

Site hosts were senior engineering managers; alumni of the school delivering the programme; established and experienced in large-scale public, private, or third sector engineering; conducting live tasks in project management, asset management, or infrastructure delivery; and located within commuting distance of the University and students’ homes. They provided students with IT accounts, laptops, smartphones, and virtual private network (VPN) access, for the duration of attachments, with which to securely access organisational information, information technology (IT) exchange servers, software, and emails. The University’s virtual learning environment (VLE) was of interest to us as researchers, since it provided for the production and submission of site attachment tasks, and forum discussions with peers and with lecturers.

4.2. Participants

Our study’s participants comprised a collaborative group of six students and two lecturers. Students were practising engineers and technicians, studying part time, sponsored by their routine workplace managers to attend HE programmes (while attachment hosting managers were consulted during our research, routine workplace managers were not). Students were mature learners, balancing part-time study with work, family, and other commitments. Their lecturers were second-career academics in engineering (cf. [42]), specialising in education for engineering in the built environment.

These participants of the research-intervention were its initiators, as is common with research following a Change Laboratory methodology. A spokesperson for the group had originally approached us to request a research-intervention, having heard of our previous work with groups in similar circumstances (e.g., [43]). The group’s primary concern was that—while they agreed that vocational readiness was beneficial to their education—the notion of authenticity was being routinely deployed by managers to promote or prohibit certain technologies, thereby normalising workplace acculturation, managerialism, and surveillance. They felt that these technology-mediated interactions constrained genuine epistemic engagement and instead encouraged performativity: industrial attachments were becoming a form of technology-mediated free labour, with their presence perceived to be interns or junior employees, as discrete from critically engaged students on industrial attachment. We agreed to meet with the group’s spokesperson, subsequently arranging an online follow-up meeting with the whole group.

Prior to conducting the research-intervention, we applied a relational and reflexive approach to ethics, alongside gaining approval from participating institutions. Participants were informed of our backgrounds and intentions, in addition to methodological arrangements, data processes, and their rights to withdraw. None withdrew, and all members of the group who had approached us took part. Participants’ pseudonyms, relevant characteristics, and their industrial attachment hosts are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ pseudonyms, characteristics, and attachment hosts.

4.3. Organisation of Workshops

In organising the workshops for our Change Laboratory research-intervention, we sought to plan progressive means to involve participants in successively and collectively undertaking an expansive learning cycle, as described above, through which the people involved are empowered to propose and enact change for themselves. Expansive learning necessitates a process which is structured yet agile, planned yet flexible, stimulating top-down and bottom-up impetus for development. We structured workshops to involve participants meeting weekly, online, where they undertook double stimulation tasks, examined ethnographic data of their failing activity (referred to in the Change Laboratory methodology as mirror data), modified partially completed models of their activity systems, and negotiated problems and potential for expansive change to authentic practice in HE. We were informed by established guidance for designing and conducting an online Change Laboratory research-intervention [44,45].

4.4. Conduct of Workshops

All interactions, discussions, and progress through tasks were digitally recorded, with participants themselves playing important and active roles to shape and direct the unfolding intervention [46].

An example from one of our workshops is shown in Figure 4. Discursive interactions took place on a cloud conferencing platform, Zoom Version 5.16. Graphical collaborative work was facilitated using web-based interactive surfaces accessed in real-time, through Microsoft Whiteboard Version 23, the shared whiteboard to the left of the figure. Mirror data were introduced by sharing screens from the particular initiator’s or respondent’s desktop, as shown at the bottom right of the figure, with still images using Microsoft Photos 2023 (continuous release) and digital video resources using Microsoft Media Player Version 11. Documentary resources were shared using Adobe Acrobat Reader (continuous release) or the Microsoft 365 suite of office applications.

Figure 4.

Arrangements for online Change Laboratory workshops.

Outside workshops, participants annotated personal disturbance diaries and tasks, in the form of interactive portable document format files. These private text entries and task stimuli were subsequently referred to in workshops, either conversationally, as images pasted onto the shared whiteboard, or as Uniform Resource Locators shared using the chat function of our cloud conferencing platform.

4.5. Data Analysis

As is typical for the Change Laboratory methodology [44,45,46], data were initially captured and analysed during and between online workshops, to allow us to re-present particular work on models, notable turns of speech, and expansive acts. These initial analyses, conducted concurrently with our facilitation of further tasks and expansive interactions, involved searching for overt evidence of problematic interactions and nascent contradictions, reacting to participants’ requests to re-present data. We also undertook examination of our amassed stock of these data on cessation of the series. We first transcribed the entire research-intervention’s interactions, beginning by checking and editing the text from the captioning service of our web hosting software, Zoom Version 5.16. We subsequently analysed the cumulative transcript, ethnographic data, and graphical work on conceptual models, using computer aided qualitative data analysis software, namely ATLAS.ti Version 22, to deductively code and categorise data using principles and themes of expansive learning, instrumental genesis, elements of activity, and contradictions.

Our online workshops yielded around 9.2 Gigabytes of multiple forms of digital data, which was encrypted and stored on secure institutional servers, including: 6.4 Gigabytes of digital recordings of the workshops themselves; 1.3 Gigabytes of ethnographic digital video recordings of failing practice; 450 Megabytes of imagery of conceptual models of the activity generated and modified by participants; and 300 Megabytes comprising electronic copies of documentary files, policy, and organisational communiqués.

In total, there were just over nine hours of interactions, which had taken place on the conferencing platform and shared online surfaces, comprising around 270 documentary and graphical exhibits, 51,000 words, and 1600 turns of speech. The data from the series of workshops are summarised in Table 2. We do not account for overlap in tasks and interactions; for example, when a participant was both speaking and engaging with mirror data, we have noted the time spent on the most discernible.

Table 2.

Summary of raw data from the series of workshops.

5. Findings

Our findings are structured firstly as an overview of the research-intervention, followed by our exemplification of turning points in addressing authenticity more directly. The former provides a relatively coarse description of how our series of workshops unfolded, and how expansive learning was engendered across the project; it also provides our rationale for focusing on specific moments in our subsequent analysis. The latter details specifically the unfolding of three workshops, exemplifying a series of notable interactions and implications for authentic technology-mediated interactions, in which participants’ attention turned from their technological devices, media, and platforms toward the qualitative meaning of the object of their authentic activity: its material purpose, meaning, and societal motive.

Table 3 summarises the data across the series of workshops, having identified all expansive acts, those which were directed at primary contradictions, and how expansive acts emerged in collective transformation through instrumental genesis. We have applied Lonchamp’s [38] typology of mediation (see Section 3.3): epistemic subject-object mediation, to understand the object and its evolution; pragmatic subject-object mediation, to transform the object of activity; interpersonal mediation, to know or act upon other subjects; and reflexive mediation, directed back toward the originating subject.

Table 3.

Types of mediation emerging during expansive acts.

The qualitatively meaningful change arising from these central workshops encapsulates our decision to make the core argument: that through exposing and aggravating contradictions for technology-mediated interactions, educational practice in HE is shown to be intrinsically authentic as a social activity. Learning thus has authenticity in and of itself, rather than solely having some sort of speculative authenticity, in its preparation of students for subsequent economic work.

5.1. Primary Contradictions

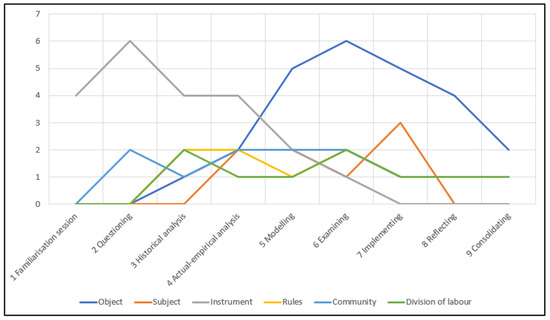

Figure 5 illustrates how primary contradictions were exposed and aggravated, along with the element of the activity that these acts were directed toward. In identifying and examining these acts, we located data which exhibited three traceable characteristics:

- Increasing the group’s understanding of something notable and discernibly contradictory about authentic technology-mediated interactions in HE;

- Moving the group beyond merely acknowledging a problem of authenticity in HE, to collective transformation through instrumentalisation and/or instrumentality;

- Leading to their identification and aggravation of a primary contradiction in authentic technology-mediated interactions in HE, recognising an irresolvable tension between use value and exchange value.

Figure 5.

Expansive acts directed at primary contradictions in elements of the activity.

The labelling of the nine unfolding online workshops (on the x-axis) is annotated with the expansive act that was predominantly—though not exclusively—designed for engendering during that workshop. The frequency (numbered on the y-axis) shows the interactions related to primary contradictions. The colour coding, explained in the legend, shows the element of the activity that was being acted upon. There are three salient observations: in the first third of our research-intervention, the primary contradictions of the activity’s mediating instruments were the most frequent to be examined; in the remainder of our research-intervention, the primary contradictions of the activity’s object were the most frequent to be examined; and throughout the series of workshops, other elements of the activity were more modestly acted upon.

Given that the drivers for this research were related to problems of authentic technology-mediated interactions, it is likely to be unsurprising that primary contradictions in the activity’s instruments were the most common to be expansively confronted across the first third of workshops. In contrast, it might seem surprising that these primary contradictions in instruments—for what is essentially a technology-mediated practice—depleted to becoming negligible in the closing workshops. As negotiations became progressively more antagonistic and troublesome, participants turned to expose and aggravate primary contradictions in the social and cultural mediators of their activity, and then in the object of their activity.

For us, this marked a deepening qualitative understanding of authentic practices in HE: participants collaboratively and expansively apprehended how their authentic learning was mediated not solely by technologies to mimic those used in economic work, but by the activity’s rules, community, and division of labour, which influence their practice in HE. The primary contradictions in rules, community, and division of labour remained at a modest and relatively constant level, yet they acted as important loci, with their exposure leading to substantive discussions of problems with the object.

Starkly, during actual-empirical analysis and modelling, expansive acts were increasingly directed at the primary contradictions of the object of the activity—its material purpose, its driver, and that which provides the activity with societal motive. The object’s primary contradictions received significant focus from the midpoint onwards, retaining dominance for the remainder of the research-intervention. The focus on the object rises rapidly in this central turning point and is sustained as the most commonly discussed element for the remainder of the workshops.

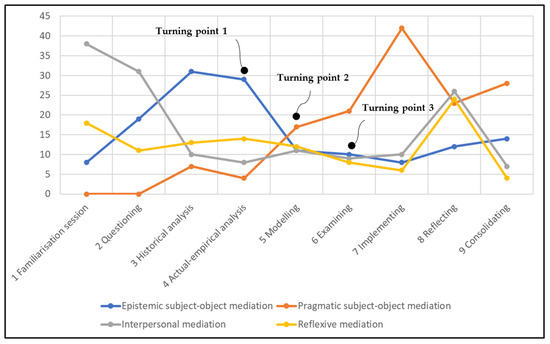

5.2. Instrumental Genesis and Types of Mediation

Figure 6 summarises our further analyses of the unfolding expansive acts, here illustrating their co-occurrence with different types of mediation of authentic technology-mediated activity, throughout the research-intervention. The labelling of the nine unfolding online workshops (on the x-axis) is annotated with the expansive act that was predominantly (though not exclusively) designed for that workshop. The frequency (numbered on the y-axis) shows the expansive acts that were exhibited in each online workshop. The colour coding, explained in the legend, shows the particular type of instrumental mediation that each line refers to in Lonchamp’s [38] typology. For us, these unfolding acts illustrate how participants increasingly recognised authentic practice in HE as something to be questioned, and socially negotiated, as distinct from being bestowed upon students through HE’s work-related technologies, policies, stakeholder interactions, and normative approaches to allocating tasks.

Figure 6.

Expansive acts co-occurring with types of instrumental mediation.

There are three overall observations to be inferred: in the first third of our research-intervention, the most frequent mediational interactions were of an epistemic subject-object nature, seeking to better understand the material purpose and societal motive for the activity; in the remainder, the most frequent mediational interactions were of a pragmatic subject-object nature, seeking to transform the material purpose and societal motive for the activity; and lastly, interpersonal and reflexive mediational interactions are more modest in frequency, yet they were represented throughout all of our workshops.

Our research-intervention was initiated with a peak of interpersonal mediation: the first workshop, which we had originally intended for familiarisation with administrative and technical arrangements, was repurposed by participants to better understand each other’s background and motives (indicative of participants taking control, which is promoted in expansive learning). This peak quickly gave way to epistemic subject-object mediation, dominant for the first third of the research-intervention, concurrent with growing interest in mirror data as participants sought to understand their activity’s purpose and motive.

In the central third of our research-intervention, during expansive acts for analysis, modelling, and examining, there was a discernible decline in epistemic subject-object mediation. The call for evidence of irrefutable failure abated somewhat, and interactions were directed toward future-oriented change and development, as participants engaged with conceptual models of proposed changes to the activity—not in a passive way, but imbued with meaning, often through socially antagonistic interactions, co-occurring with the exposure and aggravation of primary contradictions. As change and development became dominant, shown as the turning point during the central third, the object became the prevalent element for discussion at the mid-point (shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, as the crossovers during the fourth and fifth workshops, respectively).

In the latter third of our research-intervention, pragmatic subject-object mediation rose in dominance, although reflexive mediation and interpersonal mediation saw an isolated resurgence—perhaps self-evidently—during the workshop for reflecting. At this point, participants imported and shared their expansive reflections on change, negotiating implications for their educational practice more broadly, and making proposals for their further sustenance and subsequent iterations of development.

5.3. Turning Points in Addressing Authenticity

In this section we detail specifically the unfolding of three specific workshops which mark turning points, as labelled in Figure 6. We provide examples of notable data from the central third of our research-intervention, where we found that participants’ interests began to shift from their technological devices, media, and platforms toward the notion of authenticity itself, alongside the purpose and societal motive of the activity. In our extracts we show representations of the progressively concretised activity system, accompanying examples of coded transcripts, to illustrate the interplay of expansive acts, mediational types, and primary contradictions in participants’ endeavours at changing and developing authentic technology-mediated interactions. Our examples begin with the unfolding shift in attention from the activity’s instruments to its object, during the fourth session for actual-empirical analysis, followed by the fifth workshop on modelling proposed change, and the sixth on examining the changed activity’s dynamics, potential and limitations. We find these three central workshops—actual-empirical analysis, modelling, and examination—to be turning points, with salient instances of renegotiation and change in action. Each sub-section opens with a graphical representation of the evolving activity system, which we adapted from the shared stimuli used in online tasks, as illustrated in Figure 4. We then present coded transcripts, with interactions to compare with Figure 5 and Figure 6.

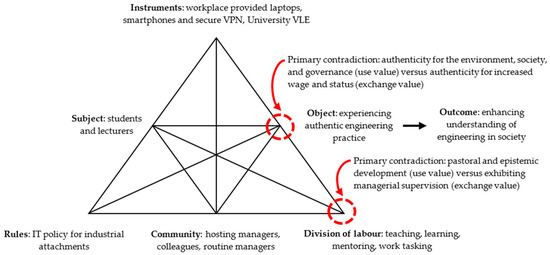

5.3.1. Turning Point 1. From Tool Mediation to the Object of Activity

The extract below is taken from the fourth workshop, in which participants undertook actual-empirical analysis to explain the existing systemic relationships of their activity. We find this interesting because it marks the point where participants began turning from claims that technological media and platforms were liable for the majority of historical failures and dilemmatic conditions, to instead problematise their activity’s object.

In the extract, OS (a lecturer) and HK (a student) turned the group from impugning technologies solely, toward examining other elements of their activity system, calling upon mirror data of failure as they did so—this is concurrently an example of epistemic subject-object mediation.

“I don’t know why they can’t just let us [subject] use ‘normal’ [air quotes] tech [instruments] with you [students] [subject], I agree this stuff’s [IT hardware] [expletive] [circling instruments], it’s locked down this [IT workstation used during industrial attachment] {instrumentalization} you can’t stream video on that, you can’t share software … I do get their [managers’] need for security [rules] but not on this bit [industrial attachment] where the intent isn’t the same [object] … Maybe there’s some work-around, something we’re just not seeing, some way of splitting apart the discussion forums into channels or something, different access levels for us and them, some forums where we care about work and security and some forums where we care about learning {instrumentalization}, but I’ve got a feeling that those access levels are set in the contract … we’ll have a look and see if we can work out a way to change them ourselves {instrumentation}.” [OS].

“I don’t think it’s all about security, … let’s just start work earlier and leave the programme [apparent sarcasm] … it’s because they [managers] need to show their own managers [community] that they’re actually actively managing us [students] and you lot as well [lecturers] [subject] … they’re still paying us don’t forget, as well as paying for us to go and work for someone else for eight weeks, so they’re understandably keeping an eye on us while we’re on remote work, that’s to get their money’s worth, not to let us learn something that threatens them [primary contradiction in division of labour] … maybe we can just suck it up … find out what’s worked in the past and just find out how to do that for an attachment submission, accepting that the real learning bit is separate from the submission [instrument] {instrumentation} … as well as setting up different forums [instrument] {instrumentalization} … they get confused about what this is for [object] … it’s the worst kept secret in the world, they pretend that they’re in it for the world’s ESG [Environmental, Social and Governance] … it’s really not, it’s all for their own gain … it’s to get their own parking spot and corner office, there’s no way that’ll ever change, the whole house of cards would fall [primary contradiction in object] …” [HK].

The extract highlights how instrumental genesis related to participants aggravating a primary contradiction, directed at line managers, as an irresolvable tension between their pastoral and epistemic development of students (as use value), versus exhibiting successful managerial supervision to their own line managers, to secure a wage and promotion advantage for themselves (as exchange value). This, in turn, provided a locus for the exposure of a primary contradiction in the object of the activity, between authentic focus on the environment, society, and corporate governance (as use value) and authenticity as a means for a wage and status advantage above one’s peers (as exchange value).

Figure 7 shows the activity system at this point (it presents a refined version of participants’ collaborative progress with actual-empirical analysis on their shared whiteboard), when participants were adapting their modelled activity system to identify internal contradictions, before using the model to negotiate their activity’s division of labour and its object.

Figure 7.

The activity system during actual-empirical analysis and turning point 1.

In working toward identifying, exposing, and aggravating these primary contradictions in the division of labour and the object, through instrumental genesis, participants vacillated between instrumentalisation (identifying and modifying mediating technologies) and instrumentation (proposing acts to develop themselves).

In the example, their joint examination of ethnographic mirror data—notably the imagery of a typical workstation which they used during their industrial attachments—provided impetus for these vacillations. These images were used in socially negotiated instrumentation (their recognition of a need to reject continued acceptance and take action for developing themselves) and in socially negotiated instrumentalisation (drawing attention to problems with media and platforms, with a need to adapt and modify technologies). Exchanges were sporadic, difficult to detangle between instrumentalisation and instrumentation, with abrupt and staccato oscillation from subject-to-instrument and from instrument-to-subject, as shown in the extracts of data.

While all types of instrumental mediation can be identified, to greater or lesser extent, these interactions most strongly exemplify epistemic subject-object mediation, the group’s collective pursuit of understanding the purpose of their authentic, technology-mediated interactions.

5.3.2. Turning Point 2. Relating the Social Structures of the Activity to the Object

In the example extract below, taken from during actions of modelling in the fifth workshop, participants proposed change as they constructed and modified their conceptual activity system on their shared online whiteboard. They moved to modelling problems and negotiating potential resolutions, socially negotiating their related implications—an example of pragmatic subject-object mediation, although we note that all of Lonchamp’s [38] types of interactions took place.

We feel this extract to be of interest in that participants vacillated between the rules of their activity and the object of their activity, collaboratively recognising the implications of policy and accepted ways of working and learning.

“If we change this [circles object] [object] but don’t change this [circles rules] [rules] we’ve got the same old [expletive] IT directives that will take centuries to change {instrumentalization}, trying to make them [rules] work with these laptops and the IT [information technology] on the desks and work mobiles [circles instruments] [instruments] … they [rules] were crap … when they were written, so they won’t be much use when we change this to something about learning at another site [circles object] [object] {instrumentalization} … but we need the reigns off to build up our own credible networks {instrumentation} and I wouldn’t speak freely, no way, not if we’re constantly having our pulse checked by the bloke who’ll be our boss again in a couple of months [division of labour] so we’ve got to do something … split the functions of the tech out somehow {instrumentalization}, it’s not as bad as a drinking-from-a-fire-hose sort of problem, but it will be soon, we need to do something about it and get better at this stuff before it gets insurmountable for us {instrumentation} …” [HK].

“We do recognise that frustration … I just want to make sure I can be there if you [students] need anything, that’s what the idea for changing this was all about [circles object] [object] {instrumentalization}, rather than you getting hold of me, say at a weekend or evening, just for me to then say ‘I can’t help you because of the IT being timed out for security [instruments], sorry but you’re on your own’ … I think it’s about me finding a sneaky work-around {instrumentation}. It’s [expletive], it’s not the tech itself though, it’s that these ITSO [information technology security officer] policies [rules] they’re good for making the auditors go away [community], they’re good for compliance … a shiny plaque at the entrance … [but] when they’re unilaterally applied to keep an eye on you it’s not right, not while you’re on this [industrial attachment], but those policies do attract a lot of business … it’s probably why we get the contracts for these [industrial HE programmes] … that’s the thing we need to dissect [circles rules] [primary contradiction in rules] … key to understanding what we can really do to change this [object].” [BM].

In the extract, HK (a student) and BM (a lecturer) relate the regulation of their activity (modelled as rules) to their deepening understanding of its object. This in turn allowed them to expose and aggravate a primary contradiction within their activity’s rules, traced to their sharing of a local disturbance during modelling of proposals for change: their annoyance with over-simplified IT policy directives for industrial attachments. These policy directives were deemed attractive to managers, for regulating workplace compliance and assurance, in contrast with what participants considered appropriate for regulating epistemic processes during industrial attachments —their critical reflection and independent thought. A primary contradiction is exposed between optimising resource allocation and social organisation of IT (use value), and exhibiting competence and compliance, attracting further business across a competitive economic value chain (exchange value).

Figure 8 shows the activity system (which we again refined from the shared whiteboard at this point), illustrating participants’ negotiated proposals for change, and the relationships between the rules of the activity and its object, which have changed from the previous iteration of their shared activity system.

Figure 8.

The activity system during modelling and turning point 2.

In this example, the conceptual model of the activity was instrumentalised as a representation of change to technology-mediated interactions: participants adapted, modified, and imbued their conceptual model of the activity with meaning to make future-oriented proposals. They used the conceptual model to represent change to their TEL activity, annotating and debating its primary contradictions (instrumentalisation), while developing their own agentic ability to make such proposals, identifying personal growth and development concomitant with meaningful change (instrumentation). Through instrumental genesis, participants came together to modify this conceptual model of the activity, to represent the potential implications of change, to simulate wanted and unwanted effects of their own proposals.

This example of the exposure and aggravation of the primary contradiction, in the activity’s rules, provided the participants with means by which they confidently sought further understanding of the object to then change it, to reflect their recognition of the need for social negotiation of authenticity’s role in engineering practice. Expansive work and learning helped them to problematise the interconnected role of institutional policy, and then to influence it in informed ways, assisting each other to understand implications for their authentic practice.

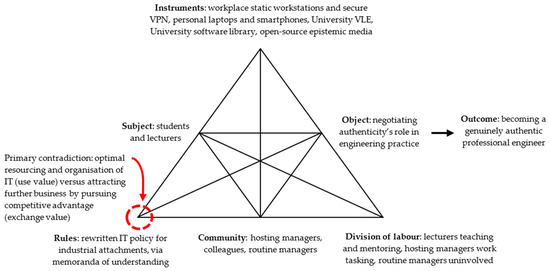

5.3.3. Turning Point 3. Grasping the Contradictions of the Activity

In the sixth workshop, which was designed to provoke the examining of proposed change, participants applied their newly modelled activity in practice to understand its dynamics, potential and limitations.

In the extract below, GC and CS (both students) identified and negotiated limitations related to the obfuscation of various roles, which necessitated the redesign of their activity’s division of labour.

“It’s hard to keep [people] away from blaming the tech for everything [instruments] … it’s [people] who are making decisions, pressing print on directives [rules] that were meant for different ways of working … we need to be learning new stuff on a different site in a different way with different people {instrumentation} … on the [policy] there’s nothing about being critical is there, so we’ll need to change that {instrumentalization} …” [GC].

“They’re [managers] paying us, and they’re paying for this entire degree to run, so they’ve got a right to tell us what to do … they’ve got the right to ask what we’re up to [community]. I’m down with that if I’m honest, we need to work out who’s doing what to make it work {instrumentation}, it’s better than finding the money myself, or being out of a job. But you can’t call this authentic, you can just call it starting work early … there’s nothing more authentic than that. Let’s just start work earlier [object]. Then we’ll know exactly what tech we need {instrumentalization}. You [GC] seem to want us [students] to be able to ask them [lecturers] clever questions, about technical stuff, but not to be able to ask our own [managers] things [community], about career stuff [circles object] [object] … I reckon that’s what authenticity’s about …” [CS].

“It’s not about ego or anything, I just reckon we’ve got to keep an eye on this [object] … what you’re [CS] saying is authentic, the need to get supervised, or line managed … it’s like other folk [community] saying ‘well now look at you, don’t you realise you’ve got to dress like us, talk like us, act like us [rules] … we’re paying for you to do it so don’t make us look like [expletive]’. That might be authentic, mightn’t it, but it isn’t what this is though [circles object] [object] … we won’t know what the difference is between learning and being a good worker, because this lot [lecturers] ask us to think critically, whatever, and that lot [managers] tell us to remember where we work [primary contradiction in division of labour], we’ve got to get them to back off at times, but we need to work out how and why {instrumentation} maybe an MOU [memorandum of understanding] would do it, and show it’s serious?” [GC].

We find this example interesting because it involves negotiating a mutual understanding of roles in sustaining proposed change—at face value an example of interpersonal mediation. Interactions concurrently referred to their own workbooks, to introduce and compare their own reflections—an example of reflexive mediation. Ensuing discussions of authenticity and its problems led to confusion of how roles and responsibilities relate to what authentic interactions—and authenticity itself—were conceived to be. A primary contradiction was then exposed in the activity’s division of labour, between the use value of allocating tasks according to epistemic outcomes, bridging workplaces with HE, versus the exchange value of allocating tasks according to contractual payments between workplaces and HE.

Figure 9 shows the status of the activity system (based on their shared whiteboard at this point), illustrating their negotiated proposals for the change to the activity’s object—the final version of the object which the group agreed upon in this research-intervention—driven by the group’s developing understanding of social and cultural mediation, not least the division of labour’s historical embeddedness and primary contradiction.

Figure 9.

The activity system during examining and turning point 3.

The exposure and aggravation of this primary contradiction in their activity’s division of labour enabled participants to enact concrete redesigns to roles and responsibilities, taking stock of epistemic potential and expertise, as discrete from solely seniority and hierarchy. There was recognition that hierarchical and vertical divisions of labour lent some pragmatic influence to those who funded HE programmes, yet funders were people whose focus was unlikely to be epistemic in nature—those who were instead concerned with business-focused drivers of monetising their workers’ attainments in HE.

In the concomitant redesign of processes and tasks, in authentic interactions, routine workplace managers were re-roled, becoming largely uninvolved other than an on-call service for involvement by exception. In draft memoranda of understanding, they agreed to formally distance themselves during industrial attachments, affording greater freedom to students and lecturers to design and sustain their own interactions, and allowing students and lecturers more autonomous critical engagements with their attachment hosts.

6. Discussion

Our paper’s findings demonstrate a lucrative role for analysing the co-occurrence of contradictions in the activity alongside instrumental genesis. Doing so allows us to show how stakeholders themselves, in collaboratively exposing and aggravating activity’s contradictions for technology-mediated interactions, can come to socially negotiate a deepened understanding of educational practice. They learn how their practice in HE has authenticity in and of itself, rather than being solely considered as preparation for authentic economic work.

Engeström’s [11] CHAT assisted us with identifying, exposing, and aggravating persistent primary contradictions—the most lucrative contradictions for sustaining change. Movements between moments of Rabardel’s [12,13] instrumentalisation and instrumentation were more difficult to detangle and separate, with participants oscillating, their pace and cadence making both instrumentalisation and instrumentation challenging to deconstruct: this issue was heightened in later stages, when researchers and participants recognised opportunities for object-oriented development, rather than making deliberate and informed judgements on the relative merits of subject-related and object-related proposals.

Of more direct benefit to sustaining and analysing the qualitative outcomes of workshops, Lonchamp’s [38] typology assisted us with differentiating forms of mediation, contributing to task design, increasing our understanding of a growing body of mediating technologies as tools (which act on the world) and signs (which act on the mind). We stated in the opening that we would not be claiming generalisability or presenting a formulaic design for authentic technology-mediated interactions: rather, we hope to have offered a deeply contextualised example of how these principles inform expansive redesign of socio-material arrangements, involving participants themselves. Our contribution is positioned at the juncture of three themes, which we problematised in our review of the literature, to which we return.

6.1. Authenticity as Preparing Students for Future Employment

Much current scholarship positions authentic learning as delivering workers ready for a neoliberal economy: generating a false dichotomy between learning and real life, then exhibiting closer alignment of the two as evidence of authenticity. We seek to contribute to a burgeoning body of scholarship which rejects such a dichotomy [17,18,19], with our paper speaking to the need for opening up expansive possibilities for authenticity in educational practice and in TEL more specifically.

We claim a point of originality in highlighting an approach which empowers participants to challenge repressive alignment with the world of work, to see such problems as loci for social action in challenging neoliberal influences on HE, exemplified in the role of mirror data inciting expansivity. Our analysis exposes how problems with vocational alignment are a source of tension for authenticity yet are concurrently a nidus for people to reject sub-optimal authentic practice.

The first turning point we analysed—from tool mediation to the object of activity—illustrates how participants were stirred to social action through epistemic subject-object mediation, from speculating about problems with technologies, to the more problematic and socially antagonistic examination of their activity’s object. There was a socially negotiated divergence, from conceptions of authenticity as solely workplace readiness: in line with Engeström [11], therefore, we suggest that authentic learning does not convey facts, but exposes opportunities for new forms of the activity; it is driven by developmental needs, manifest in daily reality and failure; and it proceeds through socially negotiated cycles.

Our contribution challenges assumptions that authentic TEL practice ought to emulate work, instead evincing—with participants themselves—material, irrefutable, relatable accounts of dissatisfaction, rooted in repressive levels of workplace alignment. On this basis, we propose that HE practice can be conceived as an authentic human endeavour in and of itself, not valued solely in terms of leading to economic work.

6.2. Authenticity as an Impetus for Policy Reform

In our paper’s earlier literature review we describe studies of meso-level policy-practice tensions, where authors invoke authenticity in stressing the perceived shortfalls of policy and its divergence from practice: with policy being represented as outmoded, immutable, and detached from daily reality, and therefore inauthentic. A burgeoning flank of studies upend this dualism [23,24], challenging people to influence policy for themselves, calling upon their own authentic practice as they do so. Our paper supplements these studies, our own point of divergence being how participants vacillate between critiquing authentic practice and influencing policy to develop their activity’s societal motive, not merely adapting practice to represent extant policy or vice-versa.

Our findings recognise how problems of authenticity are not simply redressed by compliantly aligning policy with practice: changes to policy must be sensitive to purpose and to motive, not solely an end-state. In this matter, our second turning point—relating the social structures of the activity to the object—exemplifies the qualitative implications of policy for authentic practices in HE. Analysing these acts through the lens of pragmatic subject-object mediation, we note that our participants persistently revisited stubborn contradictions, moving between the object of their activity, policy directives, and cultural norms. Bonded by a need for change, yet with a shared awareness of irresolvable tensions, our study’s participants came together to change policy, collaboratively exposing problematic social circumstances. They recognised their own original misdiagnosis, of problems with authenticity thought to be originating in mediating technologies—actually originating in the activity’s social and cultural mediators—led by their identification of problems with the purpose of authenticity (their activity’s object) and with IT policy directives and cultural norms (their activity’s rules). They co-configured revisions to policy to reflect the object of their activity, not merely to reflect their own extant practice.

We call for scholars and researchers to devote more attention to exposing and aggravating policy-practice contradictions, understanding them as loci for development and change in authentic practices in HE.

6.3. Authenticity as Exposing Students to Complex Problem Scenarios

A body of scholarship that we examine in opening this paper exposes students to problems, tensions, and complexities purported to be indicative of authentic vocational scenarios. Other scholars seek to help students in developing relational work and learning, engaging more critically with the world of work while navigating dilemmas and commitments as authentic social beings [14,29,30]. While we seek to contribute to this literature, our own point of departure is at the point where, for us, complexity does not necessitate vocational alignment, since settings of learning have ample social complexities of their own to draw upon.

Our findings have exemplified the potential of epistemic challenge for complex societal problems, and authentic practice: the reflexivity of becoming a professional engineer is sufficient for the expansive examination and development of authenticity. Our third turning point—grasping the contradictions of the activity—leads, in our analysis, to participants’ redesign of the allocation of roles and tasks in their activity, through which technology-mediated practice in HE is conceived as authentic. Change has been proposed, enacted, and reflected upon by our participants, who recognised their opportunities to adapt and enhance technologies, enmeshed with developing their own individual and collaborative capabilities in TEL practice. Our findings show a multi-voiced group, negotiating and navigating mutual understanding of enacting, sustaining, and concretising their proposed change as learners, not as aspirational workers. These intersubjective and reflective interactions exposed diverse and conflicting conceptions of authenticity, leading to their renegotiation and redesign of complex roles and responsibilities (their activity’s division of labour), in addition to proposals directed at their mediating technologies. Our findings demonstrate that the research-intervention normalised and legitimised participants’ critical engagement with complex and problematic scenarios: their examination of perspectives of diverse others. Participants recognised the social complexity of technology-mediated interactions in HE. In contrast with roles and tasks imitating the world of work, this redesign of the division of labour necessitates the reframing of HE practice as being authentic in and of itself, renouncing these experiences as being solely a segue to the world of authentic work, a conception which we commend to other scholars in researching authentic practices of HE.