A Futures Perspective on Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: An Essay on Best and Next Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Greater importance placed on the scholarship of teaching and learning.

- New power values that mean we will need university ‘leadership that could become ‘more fluid, more collaborative, able to reconfigure as needed’ (p. 220).

- ‘…challenges and opportunities of reconceptualising assessment’ that could ‘place students as co-constructors and co-designers of an educational experience that meets their diverse needs’ (p. 220). As the ‘teaching profession changes…the relationships between students and lectures needs fundamental change’ (p. 220).

- Need to change ‘that reconciles and embeds Indigenous ways of knowing alongside a shift in power relationships between ancient and newer cultures’ (p. 221).

- ‘…technological and societal changes that ripple through higher education’ and which ‘will refocus on accessibility for local and remote students globally’ (p. 221).

- ‘…government responses and funding change’ that may mean ‘more limited choices available to… [and] limits on the richness of the socio-cultural experience of students’ in universities’ (p. 221).

2. Future Universities

3. Best Practices in Learning and Teaching

- Encourages contacts between students and faculty.

- Develops reciprocity and cooperation among students.

- Uses active learning techniques.

- Gives prompt feedback

- Emphasizes time on task

- Communicates high expectations.

- Respects diverse talents and ways of learning.

- Focus on teaching and learning practice and appraisal/evaluation of the practice.

- Impact on either student learning or student experience.

- Generation of an effect size (through comparison, estimation, or correlation of impact)

- Provision well-structured representations of disciplinary knowledge/concepts in well-structured and clearly planned subject/program contexts;

- Are intellectually challenging;

- Take into account students’ goals and make clear the relevance of what they are learning;

- Deploy expert teachers who build rapport with students;

- Facilitate application/practice opportunities in authentic or simulated practice situations and give students opportunities to engage in inductive/exploratory/dialogic learning;

- Give students opportunities to interact and work with peers;

- Take into account students’ own role and agency in their learning, encouraging them to engage the meta-cognitive processes that ensure long-term encoding and retrieval, and which develop meta-cognition skills that underpin self-assessment, self-monitoring and management of their own learning.

- Interest and explanation;

- Concern and respect for students and student learning;

- Appropriate assessment and feedback;

- Clear goals and intellectual challenge;

- Independence, control, and engagement;

- Learning from students.

- Focus on learning goals.

- Create an engaging learning environment.

- Understand the importance of prior knowledge and perspective.

- Empathise and build relationships.

- Challenge and support students.

- Promote autonomy and critical thinking.

- Provide timely feedback and assessment for learning.

- Demonstrate a passion for teaching and subject matter.

- Challenge: orange

- Clarity: red

- Activating Learning/Active Learning: green

- Learning Interactions/Learning Relationships: blue

- Self-Regulation: purple

- Feedback: brown

3.1. Challenge

3.2. Clarity

3.3. Activating Learning (Active Learning)

3.4. Learning Relationships

3.5. Self-Regulation

3.6. Feedback

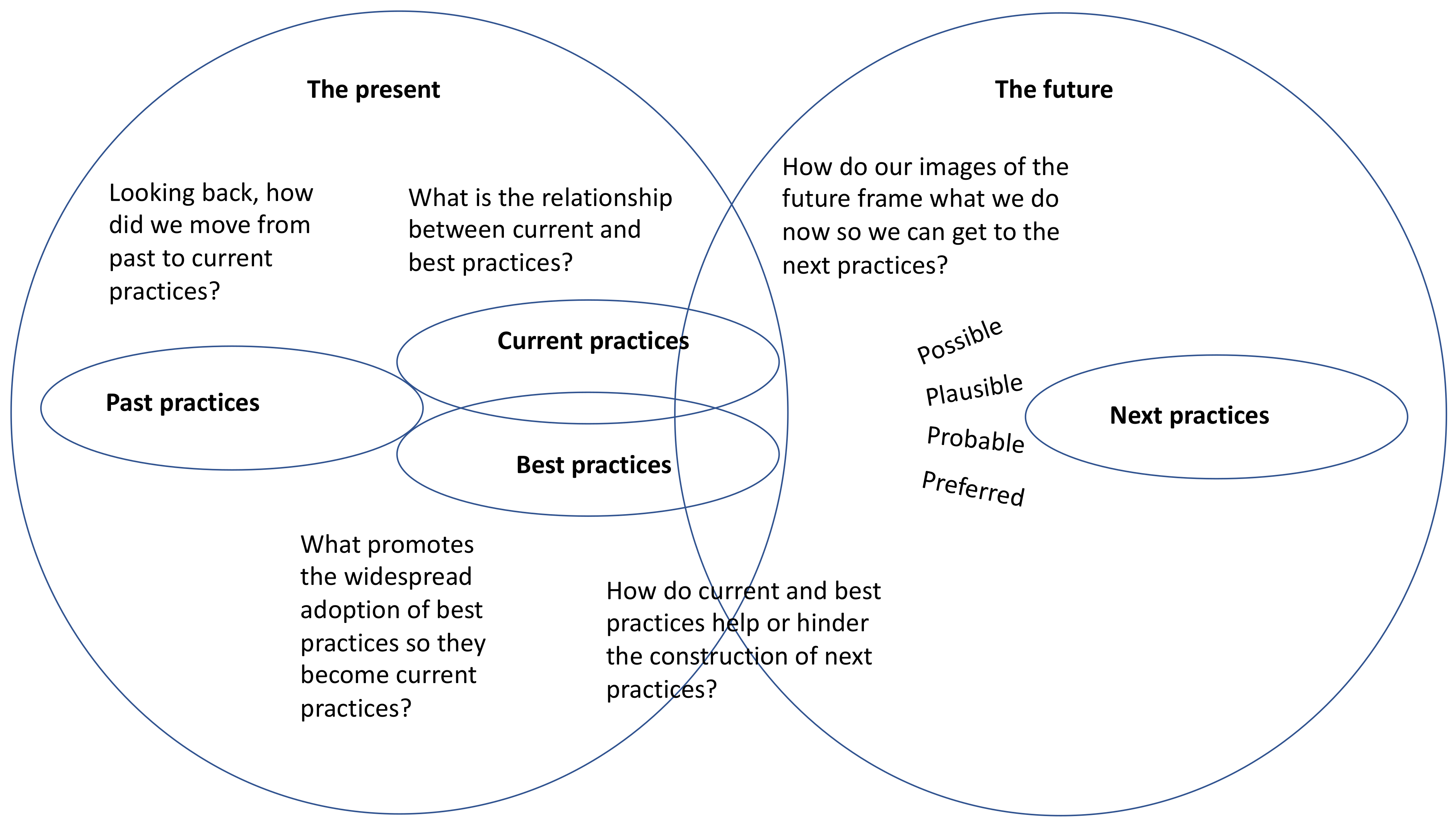

4. Next Practices in Student Learning

4.1. Next Practice in the Six Evidence-Informed Teaching Practices

4.1.1. Challenge Next Practice: An Increasing Emphasis on Ethical ‘Wicked’ World Problems

4.1.2. Clarity Next Practice: Strengthening a Focus on Macro-Level Learning Pathways

4.1.3. Activating Learning Next Practice: Ensuring the Focus Remains on Deep Learning

4.1.4. Learning Relationships Next Practice: Amplifying Social Emotional Dimensions of Learning

4.1.5. Self-Regulation Next Practice: Amplifying Self-Directed Learning Capabilities

4.1.6. Feedback: Next Practice: Provision of Feedback in Multi-Modal Forms

4.2. Possible, Plausible, Probable, and Preferred Teaching Scenarios

- Possible futures are those things which operate outside the bounds of certainty.

- Plausible futures are those things that can eventuate within our existing knowledge bases.

- Probabilities futures are eventualities that are supported by strong evidence.

- Preferred futures are about the creation a futures focussed education that is aspirational.

4.2.1. Possible Scenario—Substitution

‘What if… there is no teacher, no pupil; there is no leader; there is no guru; there is no Master, no Saviour. You, yourself, are the teacher and the pupil; you are the Maser; you are the guru; you are the leader; you are everything.’

4.2.2. Plausible Scenario—Extension of Existing Realities

4.2.3. Probable Scenario—Complementarity

‘… human and artificial intelligence can complement each other and, as a consequence, what (that) new knowledge and skills must be acquired and cultivated. By creating AI systems that are able to learn in increasingly sophisticated ways, human intelligence also becomes more sophisticated.’

4.2.4. Preferred Scenario—Transformation

‘build a new social contract for education, grounded on principles of human rights, social justice, human dignity and cultural diversity. It unequivocally affirms education as a public endeavour and a common good.’ [93] (np)

5. Conclusions

- Challenge;

- Clarity;

- Activating Learning/Active Learning;

- Learning Interactions/Learning Relationships;

- Self-Regulation;

- Feedback.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CB Insights. Education In The Post-Covid World: 6 Ways Tech Could Transform How We Teach And Learn. 2 September 2020. Available online: https://www.cbinsights.com/research/back-to-school-tech-transforming-education-learning-post-covid-19/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Senge, P.; Cambron-McCabe, N.; Lucas, T.; Smith, B.; Dutton, J.; Kleiner, A. Schools That Learn: A Fifth Discipline Resource; Nichlas Brealey Publishing: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Speak a Different Language: Reimagine the Grammar of Schooling. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2020, 48, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Scenarios for the Future of Schooling. What Schools for the Future. Schooling for Tomorrow. Center for Educational Research and Innovation, Schooling for Tomorrow Knowledge Bank. 2001. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/what-schools-for-the-future_9789264195004-en (accessed on 8 March 2002).

- Marginson, S. Higher Education in the Global Knowledge Economy. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 6962–6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Global HE as We Know It Has Forever Changed. Times Higher Education. 26 March 2020. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/global-he-we-know-it-has-forever-changed (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Marshall, J.; Roache, D.; Moody-Marshall, R. Crisis Leadership: A Critical Examination of Educational Leadership in Higher Education in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2020, 48, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, V.J.; Gabbidon, S.J. Managing Dental Education at the University of Technology, Jamaica in the Disruption of COVID-1. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2021, 49, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nyame, F.; Abedi-Boafo, E. Can Ghanaian Universities Still Attract International Students in Spite of COVID-19? Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2020, 48, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Roache, D.; Rowe-Holder, D.; Muschette, R. Transitioning to Online Distance Learning in the COVID-19 Era: A Call for Skilled Leadership in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2020, 48, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, W.; Austin, G.; Barton, K.; Nugent, N.; Kerr, D.S.; Neil, R.; Lee-Lawrence, T. A ‘Quality’ Response to COVID-19: The Team Experience of the Office of Quality Assurance, University of Technology, Jamaica. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2021, 49, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Watterston, J.; Zhao, Y. Global Distribution of Students in Higher Education. In The Educational Turn. Rethinking the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education; Coleman, K., Uzhegova, D., Blaher, B., Arkoudis, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, S.; Belton, A.; Cochrane, T.; Healy, S.; Gurr, D. Speculating on higher education in 2041—Earthworms and liminalities. In The Educational Turn: Rethinking the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education; Coleman, K., Uzhegova, D., Blaher, B., Arkoudis, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 207–224. [Google Scholar]

- Croucher, G.; Proctor, R. Australian Universities: A History of Common Cause; UNSW Press: Randwick, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, M.; Zhang, L.C.; Edwards, D.; Withers, G.; McMillan, J.; Vernon, L.; Trinidad, S. The Costs of and Economies of Scale in Supporting Students from Low Socioeconomic Status Backgrounds in Australian Higher Education; Victoria University: Melbourne, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson, S. Higher Education and the Common Good; Melbourne University Publishing: Parkville, VIC, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson, S.; Cantwell, B.; Platonova, D.; Smolentseva, A. (Eds.) Assessing the Contributions of Higher Education; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. A systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: Trends and gaps. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2023, 26, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Bai, J.Y.H.; Lee, K.; Slagter van Tryon, P.J.; Prinsloo, P. New advances in AI applications in higher education: A literature review. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2023, 26, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bacalja, A.; Beavis, C.; O’Brien, A. Changing digital literacy practices: Pedagogic frameworks for supporting digital literacy education. J. Lit. Technol. 2021, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambra, J.; Akter, S.; Mariani, M. Digital transformation in higher education: Engagement and use of e-textbooks. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2020, 23, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D. Leadership of Schools in the Future. In School Leadership in the 21st Century: Challenges and Strategies; Nir, A., Ed.; Nova Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 227–309. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; McKay, C.; Reed, C. Leadership and technology supporting quality and equitable schools through the pandemic crisis. In The Power of Technology in School Leadership during COVID-19—Insights from the Field; Kafa, A., Eteokleous, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. Should educational leadership focus on best practices or next practices? J. Educ. Chang. 2008, 9, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, V. ‘Next Practice’ in Education: A Disciplined Approach to Innovation; Innovation Unit: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hannon, V. Should educational leadership focus on ‘best practice’ or ‘next practice’? J. Educ. Chang. 2008, 9, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, V.; Mackay, A. The Future of Educational Leadership. In Five Signposts; CSE Leading Education Series; CSE: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hannon, V. Future School. How Schools Around the World Are Applying Learning Design Principles for a New Era; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Education and Work, Australia. May 2023. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/education-and-work-australia/latest-release (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Education at a Glance 2020: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, French, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, M. Introduction: Graduate Employability in Context: Charting a Complex Contested and Multifaceted Policy and Research Field. In Graduate Employability in Context; Tomlinson, M., Holmes, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gyurko, J.; MacCormack, P.; Bless, M.M.; Jodl, J. Why Colleges and Universities Need to Invest in Quality Teaching. Faculty Development, Evidence-Based Teaching Practices, and Student Success; Association of College and University Educators and American Council for Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, F.P. Conceptions of Good Teaching by Good Teachers: Case Studies from an Australian University. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2013, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrokoukou, S.; Kaliris, A.; Doncher, V.; Chaulic, M.; Karagiannopoulou, E.; Christodoulides, P.; Longobardi, C. Rediscovering Teaching in University: A Scoping Review of Teacher Effectiveness in Higher Education. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers Media: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L.S. Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus 2005, 134, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Preckel, F. Variables associated with achievement in higher education: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 565–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgo, C.A.; Ezell Sheets, J.K.; Pascarella, E.T. The Link between High-Impact Practices and Student Learning: Some Longitudinal Evidence; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh, D.D. High-Impact Educational Practices: What Are They, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter; Association of American Colleges and Universities: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.D.; Baik, C. High-impact teaching practices in higher education: A best evidence review. Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 1696–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, K. What the Best College Teachers Do; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, W. Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Development in the College Years: A Scheme; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, S. Pedagogy and Course Design Need to Change. Here’s How. Inside Higher Education. 2 September 2020. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/higher-ed-gamma/pedagogy-and-course-design-need-change-here’s-how (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Kukulska-Hulme, A.; Bossu, C.; Charitonos, K. Innovating Pedagogy 2023: Exploring New Forms of Teaching, Learning and Assessment to Guide Educators and Policymakers; Open University Innovation Report; The Open University: University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwin, P.; Boud, D.; Coate, K.; Hallet, F.; Light, G.; Luckett, K.; MacLaren, I.; Martensson, K.; McArthur, J.; McLune, V.; et al. Reflective Teaching in Higher Education, 2nd ed.; Reflective Teaching; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D. Teaching for Learning Gain in Higher Education: Developing Self-Regulated Learners; Taylor and Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, W.J. “Then you get a teacher”—Guidelines for excellence in teaching. Med. Teach. 2007, 29, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chickering, A.; Gamson, Z. Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education; AAHE Bulletin: Grandview, MO, USA, 1987. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED282491 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Ramsden, P. Learning to Teach in Higher Education; Routledge/Falmer: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden, P. Learning to Teach in Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, S.A.; Bridges, M.W.; DiPietro, M.; Lovett, M.C.; Norma, M.K. How Learning Works: Severn Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J. Visible Learning: The Sequel: A Synthesis of over 2,100 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Roska, J.; Trolian, T.L.; Blaich, C.; Wise, K. Facilitating academic performance in college: Understanding the role of clear and organised instruction. High. Educ. 2017, 74, 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory. In The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Cognition in Education; Mestre, J.P., Ross, B.H., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C. Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Maidenhead, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus, H.L.; Dreyfus, S.E. A Five-Stage Model of the Mental Activities Involved in Directed Skill Acquisition; Operations Research Center, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Astin, A.W. Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. J. Coll. Stud. Pers. 1984, 25, 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, D.; Shipley, T.F. The Curious Construct of Active Learning. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2021, 22, 8–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, T.; El Hakim, Y. (Eds.) An introduction to student engagement in higher education. In A Handbook for Student Engagement in Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, J.M. Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning, 2nd ed.; Jossey Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bransford, J.D.; Brown, A.L.; Cocking, R.R. (Eds.) How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Light, G.; Cox, R.; Calkins, S. Learning & Teaching in Higher Education: The Reflective Professional; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Race, P. Making Learning Happen: A Guide for Post-Compulsory Education; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arons, A. Critical Thinking and the Baccalaureate Curriculum. Lib. Educ. 1985, 71, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, M.; Ajjawi, R.; Boud, D.; Molloy, E. Identifying Feedback That Has Impact. In The Impact of Feedback in Higher Education: Improving Assessment Outcomes for Learners; Henderson, M., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., Molloy, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie JCrivelli, J.; Van Gompel, K.; West-Smith, P.; Wike, K. Feedback that leads to improvement in student essays: Testing the hypothesis that “where to next” feedback is most powerful. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers Media: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2021; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wimshurst, K.; Manning, M. Feed-forward assessment, exemplars and peer marking: Evidence of efficacy. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackel BPearce, J.; Radloff, A.; Edwards, D. Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education; Higher Education Academy: Heslington, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, T. Effective Feedback in Digital Environments, Melbourne CSHE Discussion Paper, Melbourne, Australia. June 2020. Available online: https://melbourne-cshe.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/3417079/effective-feedback-in-digital-learning-environments_final.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Nicol, D. From monologue to dialogue: Improving written feedback processes in mass higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D.; Boud, D. The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, J.; Ajjawi, R.; Boud, D.; Dawson, P.; Panadero, E. Developing evaluative judgement: Enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. High. Educ. 2017, 76, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scot, C.L. The Futures of Learning 1: Education, Research and Foresight Working Papers: Why Must Learning Content and Methods Change in the 21st Century; UNESCO: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). The Universal Learning Programme: Educating Future-Ready Citizens (UNESCO); Technical Report: Curriculum Analysis of the OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030; UNESCO: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Herodotou, C.; Sharples, M.; Kukulska-Hulme, A.; Rienties, B.; Scanlon, E.; Whitelock, D. Innovative Pedagogies for the Future: An Evidence-Based Selection. Front. Educ. 2019, 4, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030: Conceptual Learning Framework (OECD); OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kahu, E.R.; Ashley, N.; Picton, C. Exploring the Complexity of First-Year Student Belonging in Higher Education: Familiarity, Interpersonal, and Academic Belonging. Stud. Success 2022, 13, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, L.A.; Thomas, C.L. High-impact teaching practices foster a greater sense of belonging in the college classroom. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2022, 46, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahsood, S.; Kift, S.; Thomas, L. (Eds.) Student Retention and Success in Higher Education Institutional Change for the 21st Century; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition, Rev. and expanded 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012; Volume 37929. [Google Scholar]

- EDUCAUSE. EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: Teaching and Learning Edition. 2023. Available online: https://library.educause.edu/resources/2023/5/2023-educause-horizon-report-teaching-and-learning-edition (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Birdwell, T. Learning spaces. In 2023 Educause Horizon Report; Teaching and Learning Edition; EDUCAUSE: Denver, CO, USA, 2023; pp. 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Toffler, A. Powership: Knowledge, Wealth, and Power at the Edge of the 21st Century; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mandernach, J. Innovation in research and teaching. In 2023 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report; Teaching and Learning Edition; EDUCAUSE: Denver, CO, USA, 2023; pp. 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, R.; Henriques, R. Decoding student success in higher education: A comparative study on learning strategies of undergraduate and graduate students. Stud. Paedagog. 2023, 28, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Handley, K.; Millar, J. Feedback: Focussing attention on engagement. Stud. High. Educ. 2011, 36, 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minocha, S. Towards Imaginative Universities of the Future. University World News. 15 August 2021. Available online: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20210811141039355 (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Knowles, M. Self-Directed Learning; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson, A.; Pool, R. Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research; UNESCO: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sharples, M.; Pérez y Pérez, R. Story Machines: How Computers Have Become Creative Writers; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Avvisati, F.; Jacotin, G.; Vincent-Lancrin, S. Educating Higher Education Students for Innovative Economies: What International Data Tell Us. Tuning J. High. Educ. 2013, 1, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). Reimagining Our Futures Together, A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379764_eng (accessed on 12 February 2022).

| Chickering and Gamson 1987 [47] 7 Principles of Good Teaching | Ramsden 2003 [48] Key Principles of Effective Teaching | Bain 2004 [40] “What the Best College Teachers Do” | Smith and Baik 2021 [39] High Impact Practices |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jarni, N.; Gurr, D. A Futures Perspective on Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: An Essay on Best and Next Practices. Trends High. Educ. 2024, 3, 793-811. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu3030045

Jarni N, Gurr D. A Futures Perspective on Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: An Essay on Best and Next Practices. Trends in Higher Education. 2024; 3(3):793-811. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu3030045

Chicago/Turabian StyleJarni, Nada, and David Gurr. 2024. "A Futures Perspective on Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: An Essay on Best and Next Practices" Trends in Higher Education 3, no. 3: 793-811. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu3030045

APA StyleJarni, N., & Gurr, D. (2024). A Futures Perspective on Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: An Essay on Best and Next Practices. Trends in Higher Education, 3(3), 793-811. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu3030045