Abstract

The aim of this paper is to cultivate the future in Higher Education (HE), firstly by looking backward and learning from the past, then by looking around and questioning the present, and finally, by looking forward and imagining the future of HE. This paper seeks to answer the question of how HE can foster students’ life-world becoming, their emancipatory competence with wisdom pedagogy. The research method is based on selected literature from German educational philosophy (Herder, Humboldt, Hegel, Heidegger, and Gadamer) and on recent international publications discussing Bildung, self-cultivation, and life-world becoming in relation to HE. The findings show the need for moral education to enhance students’ flourishing in life with wisdom pedagogy. In the future, HE needs to focus more on cultivating character, emancipatory competence, life-world becoming, values, justice, trust, truth, and intellectual virtues such as intellectual humility, curiosity, open-mindedness, and courage. This paper offers a framework for synthesizing the epistemological and ontological goals of HE, and a framework that presents the place and role of wisdom pedagogy in developing emancipatory competences. This paper argues for applying wisdom pedagogy and its methods by teachers in HE to foster students’ capacity to flourish in life. The paper calls for more debates and research in understanding wisdom pedagogy in HE.

1. Introduction

| Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow. |

| The important thing is not to stop questioning. |

| -Albert Einstein- |

Higher educational institutions face unprecedented challenges such as high interconnectedness and high complexity in their social and natural world. There is a dilemma about future trends, the main goal and tasks of Higher Education (HE) in the 21st century, and about the future of universities and university pedagogy. In annual meetings in Davos, global business leaders express their views, visions, and predictions about the future state of the world [1]. Based on Global Risks Perception Surveys (GRPS), the World Economic Forum [2] (p. 12), [3] (p. 14) annually predicts global economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal, and technological challenges and risks that might impact our lives. The global challenges are climate action failure, extreme weather, biodiversity loss, social cohesion erosion, livelihood crises, infectious diseases, human environmental damage, natural resource crises, debt crises, and geoeconomics confrontation [3] (p. 14).

The research problem is: How can university education enable learners to act in this environment, solve wicked problems [4,5,6,7,8], and prevent future global crises? Therefore, the following fundamental questions arise: What is the purpose of education? What role does education play in the life of a person? Education is about people; it is about the future. Primary education and parents nurture young children, teach them what is good, what is bad, what is right, what is wrong, and what behavior and attitude adults expect from them. Based on their values, knowledge and accumulated experience, adults teach children how to be in the world. Secondary education, the broader community and friends of adolescents broaden their views, teach them what to know, to develop their skills and knowledge, help them to see things differently, foster them to question what has been taught to them earlier, encourage them to make their own decisions, to learn from their failures, experience a broader world around them, and help them to experience the challenges of being in the world. This paper seeks to answer the question how HE can foster students’ emancipatory competences, that is, their life-world becoming with wisdom pedagogy.

The author of this paper believes that the main dilemma about the core goal of HE is if it should focus on vocational goals and enhance knowledge, skills, competences for the employability of students, and/or whether it should focus on non-vocational goals such as cultivating moral virtues, wisdom, and the formation of good, democratic citizens for a better world. Adults enter HE with the aim of deepening their knowledge in specific fields (such as engineering, management, social sciences, education, art, and so on); their basic knowledge, skills, competences, personalities, values, and attitudes are already mostly formed. What and how could HE teach to adult students? This paper argues that in HE, students cannot only enhance their knowledge, skills, and competences, and learn to combine their factual and theoretical knowledge with their practices in the world, but students can learn their lifelong becoming in the world. It might be a simplification; however, the author believes that the role of education in peoples’ lives is to be, being, and becoming in the world. To put it simply, education is about cultivating future generations.

The research method of this paper is based on selected literature from German educational philosophy (Herder, Humboldt, Hegel, Heidegger, and Gadamer) and on recent international publications [9,10,11,12,13,14] discussing the theory and concept of Bildung, self-cultivation and human existence in the world. Bildung is a controversial, ambiguous, and highly debated concept that focuses on individual growth (i.e., self-development, -perfection, -formation, -cultivation, and -growth). Some authors argue that it cannot even be translated. It is difficult to apply it today in HE. The findings demonstrate that there is a need for rethinking the goals and tasks of HE when the world is highly interconnected and full of wicked problems that need solutions. Furthermore, there is a need in HE to enhance altruistic thinking and to cultivate adult learners’ becoming in the world. It is not enough to provide them with the knowledge, skills, and competences demanded by working life but, more importantly, HE should shift its focus to enabling learners with ethical and moral values that support their becoming good citizens and successful actors in the 21st century.

This paper is organized into five sections. The first section introduces the extraordinary challenges of higher educational institutions, the need for rethinking the tasks of HE, and presents the main research question. Section two explores the concept of Bildung in German educational philosophy and in current literature, and presents the findings. Section three outlines the current macro environmental forces of HE and the eight ecosystems of the university. Section four is a discussion about the future trends in HE, which calls for more wisdom education. It presents two frameworks: the first framework illustrates the synthesis of epistemological and ontological goals of HE, and the second one presents the place and role of wisdom pedagogy. In the Conclusion section, the paper outlines further educational research directions and calls for more research in wisdom pedagogy.

2. Looking Backward—Exploring the Concept of Bildung

2.1. Ambiguity of the Concept

The aim of this paper is to redefine the tasks of HE in the 21st century. For this purpose, the origin and characteristics of the concept of Bildung is explored, as it is highly relevant to cultivating students’ lifelong becoming in the world. The term Bildung is derived from Bild (image), which corresponds to the Latin Formatio (form) being the equivalent to Bild. Bildung means self-formation, -cultivation, -perfection, and -improvement, character formation, personal growth and perfection, acting in the world, and continuing formation of the whole person. Therefore, Bildung is more than just developing learners’ knowledge, skills, and competences. It focuses also on moral virtues and wisdom, on connecting the self with the world, on attitudes and values, on integral human formation, and on cultivating the person as a whole.

However, Bildung is a very ambiguous and highly debated concept in HE today. Bildung cannot be translated into other languages, and it is difficult to define what Bildung is. Lindskog [11] identifies:

twelve main meanings of the concept as used in contemporary Swedish educational debate: general or non-specialized knowledge, cultural activity (going to the theatre, etc.), democratic education, moral responsibility and reflectiveness, ability to understand things by placing them in wider contexts, knowledge in certain essential parts of the humanities and social sciences (such as history), ability to transform information into knowledge, personal development, learning skills, critical thinking and a critical attitude, multidisciplinary knowledge, and ability to see things from more than one perspective.[10] (p. 2)

Similarly, Alves [9] argues that:

Bildung is one of the fundamental concepts of modernity and the most ambiguous concept of German pedagogy. … Bildung is not equivalent to teaching or education but evokes a series of ideas … interiority, totality, development, vocation, promise, the action of shaping, modelling, deepening and perfecting one’s own personality, the construction of a personal culture, etc.[9] (pp. 2–3, emphasis original)

Regardless of the ambiguity and diverse contemporary interpretations of the concept, it is important to look back in history and to explore its origins in the works of the German philosophers Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835), Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), and Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002), who are the key developers of the theory and concept of Bildung and human existence.

2.2. Originating the Concept

In the second half of the 18th century, Herder developed the concept of Bildung. Alves [9] explores the semantic history of Bildung over time in Germany: “from the beginnings in the late Middle Ages to its institutionalization in the German school system in the nineteenth century” [9] (p. 1). Alves argues that “influenced by Leibniz, Herder opposed the mechanistic view spread by the Newtonian model of the world and instead, proposed an organistic view of life and history interpreted as dynamic phenomena in perpetual becoming” [9] (p. 5). Herder [15] viewed a society as an organic whole, and history as a process of education of the human species; “Herder had a blind faith in nature, in man and in the ultimate development of reason and justice” [16] (p. 125). Concurring with Herder’s organistic view of life and with the continued becoming of a person [15], the author of this paper argues that what it means to be human is a contemporary question even today, in the age of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR).

2.3. Applying the Concept to University Education

In the second half of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, Humboldt (1767–1835) developed his theory. He argued that every citizen should seek by all means to educate and to cultivate herself or himself. For him, the development of individuality is a natural process:

Humboldt thought of the ideal of Bildung according to the model of free moral action in Kant. To cultivate oneself, to strive for the continuous self-improvement of one’s personality, is seen as an end in itself, independent of any utilitarian or pragmatic reason, a true categorical imperative.[9] (p. 6)

Humboldt’s conception of university education was that it should enable everyone to receive an integral human formation. According to him:

The task of education was not to adapt the individual to the world, to train him with useful knowledge and skills, but to awaken the inner forces, creativity, and critical judgment to transform the world and to realize within itself the ideal of humanity.[9] (p. 10)

This clearly demonstrates that, for Humboldt, university education should go beyond its vocational goals (i.e., answering the markets and governments’ demand for knowledge, skills, and competences). University education should empower persons’ continuous becoming in the world.

2.4. Philosophical Roots of the Concept

Currently, Lumsden [12] discusses Bildung in Hegel’s (1770–1831) philosophy of history. Hegel developed his theory in the second half of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. Kant argued that civilization “leads to the development and establishment of structures and standards external to an agent by which their worth is judged and that guide ‘good conduct’. Bildung by contrast is the internal domain in which our moral development is cultivated” [12] (p. 446, emphasis original). This division of external and internal domains is not supported by Hegel. He does not agree with “the divisions between culture, civilization and Bildung in any general or systematic manner in his objective spirit” [12] (p. 446). Bildung is the primary focus of Hegel’s discussion of the role and influence of culture on the spirit’s development. According to Lumsden [12] (pp. 447–448), there are four elements in the role of Bildung in the philosophy of history of Hegel: (1) it allows individuals to adopt the perspective of the universal, (2) it is involved in and captures the embodiment of norms, (3) it is critical to overcoming the subjectivism of Kantian morality and autonomy, and (4) it has a central role in the development of world history.

Hegel emphasized the role and importance of the cultivation of reflection. For him, “the appreciation, examination and adoption of external influences and different points of view are essential to the development of spirit, to the idea of Bildung” [12] (p. 448). For Hegel, Bildung “is both the process by which norms and values are formed as well as the outcome that captures the way in which norms are collectively produced” [12] (p. 455); “Bildung is Hegel’s term for understanding how we can be formed such that we think and act ethically, mediated through our sociality. The objective aspect of Bildung describes an ongoing form of social relation that we cannot transcend” [12] (p. 457). Lumsden argues that:

The original sense of Bildung primarily conceives it as a process of self-formation. Hegel preserves this original subjective sense of the term, but he gives it a much more expansive role, placing it at the very centre of cultural and historical change.[12] (p. 459)

Hegel’s idea of Bildung sends a message to HE today, too, as it emphasizes the importance of the context (culture, natural and social environment, and time) in the perpetual formation of the self. Furthermore, Hegel underlined not only the role of reflection in self-development, but the understanding of the diversity of thinking of others (thesis, antithesis), the dialectic process (thesis-antithesis-synthesis) of how thinking develops, and the reconciling unity (synthesis) of thoughts and the context: “the movement of thought, … is the same as the movement of things; in each there is a dialectical progression from unity through diversity to university-in-unity. Thoughts and being follow the same law; and logic and metaphysics are one” [17] (p. 296). Hegel considered struggle as the law of growth, “character is built in the storm and stress of the world; and a man (sic) reaches his (sic) full height only through compulsions, responsibilities, and suffering” [17] (p. 297). Hegel’s views of formation of self and thoughts are relevant to the challenging tasks of HE today.

In the 20th century, Heidegger (1889–1976) “aimed at a phenomenological analysis of human existence in respect to its temporal and historical character” [16] (p. 124); “under Kirkegaard’s influence, he pursues an ‘existential’ analysis of human experience in order to discuss the original philosophical question of being in a new way” (Ibid.). Heidegger focused on the fundamental problem of being and time. Therefore, his new approach to the problem of being could have a message for the recent rethinking of the tasks of the HE and university. Gadamer (1900–2002) lived in the 20th century. Bohlin [10] argues that:

Gadamer develops a ― negative theoretical analysis of self-cultivation as a process of wrestling with problems without predefined answers, even without predefined formulations of the problems themselves. Transformative learning theory … explains how teachers can work didactically to promote such processes of self-cultivation.[10] (p. 5)

With Gadamer’s negative didactic method of not providing solutions to the problems to be solved, the teacher motivates the students to actively search for solutions themselves. This means that:

The student or participant in the process is (i) made to reflect on a certain problem, (ii) presented with more than one possible solution without being told that this solution or the other is the right one, and thereby (iii) provoked or stimulated to think independently on the problem.[10] (p. 6)

Therefore, in Gadamer’s Bildung method, the teacher does not impose certain values on the students but rather activates others to think critically, reflect in practice, learn, and develop their own values and character. Gadamer’s hermeneutic rethinking of the Bildung concept is relevant to this paper as it illustrates how the teacher can cultivate others’ becoming in the world.

2.5. Transforming University Education and Pedagogy

In a recent paper, Miyamoto [13] presents Humboldt’s educational reform, Bildung theory, didactic principle to curriculum studies. The goal of education by Humboldt is to encourage students to deepen their view of the world through academic disciplines such as language, history, mathematics, gymnastics, and aesthetics [13] (p. 9). However, it requires a reconstruction of the traditional didactic triangle of teacher-student-content into a two-dimensional model, where a vertical educative process by the teacher enables a horizontal process of Bildung through which the student connects him or herself with the world [13] (pp. 10–11). It is important to note that in the reconstructed didactic model the teacher is not connected with the student and the material but with the method (i.e., with the Bildung process between the student and the world). The challenge for HE today is to find the appropriate educational processes, methods, and pedagogy by which the teacher evokes intrinsic motivation and aspiration in the learners.

In their contemporary publication, Sjöström and Eilks argue that “Bildung is a theory of defining the aims and objectives of any education” [14] (p. 55). According to them:

Bildung was never understood as something one can be taught, but Bildung-oriented education is suggested as a way for everyone to support developing Bildung on their own. Bildung in a theoretical view is more of a concept of achieving capacity and skills than a set of facts and theories to be learned. Bildung is viewed more as a process of activating potential than a process of learning.[14] (p. 56)

The meaning of Bildung is highly debated in Germany and in Scandinavia. Sjöström and Eilks recently identified five educational traditions directly related to the Bildung theory: (1) classical Bildung, (2) liberal education, (3) Scandinavian folk-Bildung, (4) democratic education, and (5) critical-hermeneutic Bildung [14] (p. 57). However, they also agree that Bildung is a rich but complex concept that has had upheavals in popularity through time. According to them, since the 1980s, the concept has enjoyed a renaissance.

2.6. Findings

This paper focuses on rethinking the tasks of HE and on finding out what role HE could play in adults’ lives. For this purpose, the Bildung concept and method was explored in German educational philosophy and contemporary international literature. The findings are threefold: (1) multiple contemporary understanding and interpretations of the concept, (2) philosophical roots of the concept, and (3) applications of Bildung to university education and pedagogy.

Firstly, the multiple understanding and interpretations of Bildung show that it is more than just developing learners’ knowledge, skills, and competences, it has a moral and ethical purpose not only vocational goals [10]. It focuses on moral virtues and wisdom, on connecting the self with the world, on their attitudes and values, on integral human formation, on cultivating the holistic person, and on life-world becoming of students. Bildung has several meanings, interpretations, and forms [10,11,14]. The concept is highly ambiguous and it cannot be translated into foreign languages due to its multiple meanings and diverse ideas [9].

Secondly, the concept of Bildung is a rich idea that has its roots in philosophy. It was originally developed in the second half of the 18th century and has been rethought since then (Herder, Humboldt, Hegel, Heidegger, and Gadamer). The original concept is individualistic, focuses on self-development, -perfection, -formation, -cultivation, and -growth, and less on others. Later, Hegel and Heidegger emphasized the importance of the context, the unity of culture, natural and social environment, and time [12,16] as well as understanding different and diverse views [17]. Today, the concept of Bildung is highly debated [14] and considered to be problematic and ambiguous [9].

Thirdly, the findings demonstrate that applying the original Bildung concept and method in today’s educational practices and contexts is difficult [10,13,18,19]. Consequently, it is understandable that the concept has numerous implementations (German-Bildung, Nordic-Bildung, Scandinavian-Bildung, Swedish-Bildung, Brazilian-Bildung, and others). However, the study of the literature revealed that, since the 1980s, Bildung has realized a revival [14]. The next section of this paper focuses on contemporary trends in HE and on finding out how learning from Bildung could be applied in cultivating the emancipatory competences and life-world becoming of students.

3. Looking Around—Current Trends in Higher Education

Higher Education or third-level education is a broader category than university. University is a social institution and it is part of HE. Higher educational institutions also include polytechnics, universities of applied sciences, colleges, and other institutions that provide academic degrees for students. This section does not discuss trends in HE in specific countries or regions, but rather it focuses on the current general trends in HE and in university education.

General factors influencing HE are demographic, geographic, socio-cultural, political, economic, technological, ecological, and legal environments. The trend in the aging population is increasing the demand for adult education, continuing education, and lifelong learning. Millennials and generation Z [20] have different values, needs, and attitudes that need to be considered by HE. Demographics also impact teacher education owing to less availability of qualified young teachers. Geographic factors and physical difficulties to access HE force higher educational institutions to increase their online courses and distance learning opportunities. Socio-cultural trends, religious groups, minorities, and immigrants impact HE because it needs to adapt and be sensitive to the diverse cultural backgrounds of students by offering specific language courses, access to free education, and open university courses. Political factors like democracy [21,22], freedom of academic exchange and dissemination, freedom of academic and cultural expression, freedom to research and teach, freedom of discussion of women and gender issues, the institutional autonomy of universities, campus integrity, freedom of speech, the government censorship effort of media, and the harassment of journalists all influence HE.

The Impacts of economic factors on HE cannot be ignored either. Economic growth, the disposable income of citizens, the distribution of wealth, unemployment, demands of the labor market, inflation, banking infrastructure, exchange rates, and the availability of credit all have an impact on HE. For example, HE reacts by determining and rethinking the fees of education, providing free courses, increasing offers for the unemployed, by organizing special skills and developing opportunities for employees. Technological factors such as innovation, access to technology, technological infrastructure, and students’ access to digital tools force HE to move to distance education and to provide online learning possibilities. Environmental factors [1,2,3] like recycling policies, waste disposal, energy consumption, and environmental protection create new opportunities for HE to do research, to integrate the global environmental challenges into education, and to develop their students’ attitudes towards the environment. Labor, safety, labor market, employment, health and safety, product, and research regulations, as well as patent, copyright, and environmental protection laws are the main legal factors HE should consider.

Higher education and the university are closely interwoven with their external environment, which is impacted by all the factors previously mentioned. However, HE is not a passive actor in society that only reacts to its forces, but it plays an active role in forming society. The interrelatedness and interactions between society’s forces and the university are expressed with the ecological approach to study the university as an ecosystem. The living space of universities is their ecosystem and this “space is the expression of society. … space is not a reflection of society; it is its expression” [23] (p. 410). Castells argues that “our society is constructed around flows: flows of capital, flows of information, flows of technology, flows of organizational interaction, flows of images, sounds, and symbols” [23] (pp. 411–412). The building elements of society are connected with each other by nodes and hubs during their constant exchanges and interactions. An ecosystem is a dynamic, open system of interconnected elements, which are constantly interacting and influencing each other. In society, there is an infinite number of ecosystems. Universities are ecosystems too. Therefore, HE and universities, at the same time, are formed by their connections to other ecosystems and they are forming and impacting the ecosystems connected with them.

Taking the ecological perspective helps to understand the role of universities [24,25,26]. Barnett writes “the university is an institution that is interconnected with several zones of the world … knowledge, learning, culture, persons, and society itself, as well as the natural world … The ecological perspective, therefore, opens horizons for the university” [24] (p. 8). Further, he explains the seven most important ecosystems of the university [25] (pp. 55–68):

- The knowledge ecosystem—university as one source of knowledge production and circulation; knowledge and knowing have different types (scientific knowledge; practical, instrumental knowledge; emancipatory knowledge). University, however, is not the only producer of knowledge. Knowledge can be created by practitioners, professionals, individual persons, communities, and organizations, and it could be local, international, and global knowledge too. Therefore, concurring with Barnett, it would be better to talk about knowledge ecologies and knowledges (i.e., tacit, explicit, scientific (episteme), practical (techne), critical, reflective (phronesis) knowledge, and so on) in plural, not only about knowledge as such.

- The ecosystem of social institutions—Universities are one type of social institution. Social institutions are public, private, local, international, global, professional organizations, government, regulator bodies, ministries, policymakers, healthcare, NGOs, and so on. These social institutions, together with universities, form the ecological system of social institutions in society.

- The ecosystem of persons—human subjectivity, identity, and actors (agents) in society form their ecosystem too. Universities are responsible for forming the identity of their students, enhancing their critical thinking, helping them to address global challenges of the world, and shaping their values and attitudes with pedagogy. This paper argues that universities’ connections with the ecology of persons are the most important way for universities to form society.

- The economy as an ecosystem—Universities are contributors to the economy by conducting research, solving business problems in a collaboration with their partners, and by educating students. Organizations invest in universities’ research and expect returns on their investments. Universities create economic value and contribute to economic growth and the well-being of the whole of society, and, during this process, they safeguard moral values and ethical principles (social responsibility, health and environmental consciousness, sustainability, research ethics, and scientific responsibility).

- Learning ecosystem—Universities are responsible not only for the learning of individuals but also for the learning of the whole of society through media connections with the public, and by collaborating with the ecosystems of social institutions, the economy, and persons.

- Culture ecosystem—Barnett feels that the idea of culture is a challenge for universities and it needs to be considered with caution. He writes: “A first step is to acknowledge that the university might pretend to be above and beyond culture, but that it is inherently a culture-laden zone. … The ecological university, then, cannot be culture free, but, to the contrary, possesses a culture that turns on dispositions of care, openness and generosity” [25] (p. 65, emphasis original).

- The natural environment ecosystem—This ecosystem cannot be ignored by the university. The university mission, vision, values, curriculum, and pedagogy should raise the students’ awareness of the challenges and global problems not only of society but the natural world too [1,2,3].

In his recent book [26], Barnett extends his earlier model of seven university ecosystems by adding polity as an additional ecosystem. Indeed, politics plays an important role in the life of the universities. It poses restrictions, and opportunities for the university. According to Barnett, when studying university and HE as ecosystems, “there are no less than eight ecosystems that should especially come into view here, those of knowledge, persons, social institutions, the economy, the polity, culture, learning and the natural environment” [26] (p. 240, emphases original). He strongly claims that “in the twenty-first century, the university cannot be understood independently of those eight” ecosystems [26] (p. 241). Concurring with his argument, this paper argues that the roles and trends in HE, the tasks of universities, their reason for existence, and their missions, goals, and values should be viewed in close interrelatedness with their ecosystems.

In brief, higher educational trends are interwoven, determined, and influenced by the macroenvironmental forces, by the ecosystems of HE. Nowadays, universities experience the strong influences of labor market forces, managerialism, corporatization, a pragmatic approach to pedagogy, de-professionalization of academic work, the rise of consumerism, and the commoditization of knowledge [27] (pp. 104–105). Morley argues that “the University of Today is diversified, expanded, globalised, borderless/edgeless, marketised, technologised, neo-liberalised and potentially privatised. Dominant discourses and imagined policy futures focus on excellence, innovation, digitalisation, globalisation, teaching and learning, employability and economic impact” [28] (p. 27).

4. Looking Forward—Discussing Future Trends in Higher Education

4.1. Future Goals of Higher Education

The roles of knowledge and knowing, as the main production factors of the knowledge economy, have increased. Higher education applies existing knowledge, and it produces new knowledge that is useful for individuals and for society as a whole. Barnett, however, worries about this trend in HE, and he has concerns about HE being in the ‘knowledge business’ because, in his view, “terms such as insight, understanding, reflection, wisdom and critique are neglected in favour of skill, competence, outcome, information, technique and flexibility” [29] (pp. 15–16).

Knowledge produced by universities, however, has not been for everyone in society. Universities have gone through different evolutionary phases. Taking a historical perspective, Matthews [30] presents the genealogy (i.e., development over time) of the form of universities. He describes three modes of the universities, namely: mode 1—the elite ivory tower being a typical form in enlightenment, mode 2—the mass factory as the dominating form during the industrial revolution and knowledge economy, and mode 3—the universal network as a present form of the universities in the 4th industrial age and network society. However, he admits that these modes of universities could co-exist and be found in different societies. Based on Matthews’ [30] genealogical approach, the present mode of universities is the universal network university. It focuses on economic contributions, the efficiency of education, costs, the personalization of education, and on advancing individual goals, employability, careers, and salary maximization. In the universal network form of the university, technology will play an important role, as we have already experienced the boom of virtual courses, virtual universities, and distance learning opportunities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Is there a threat to the core mission and to the identity of the university in the universal network mode? The universal network mode of the university is characterized by unbundling the functions of the university, demolishing its borders, changing its identity, and threatening its role in society [31,32], and it leads to multiple roles and forms of universities in society. Several educational experts [27,28,33] worry about the future of the university trying to be and to do too many things. In the age of multiversity there is a danger of losing the identity of the university. The postmodern university is “virtual, reflexive, fragmented, ambiguous, de-centred, contradictory, devoid of fundamentals, inconsistent, and multi-faceted” [27] (p. 106), and:

The university has ceased to be a place for public debate—agora or forum. … the place of critique and wisdom has been converted into a market place, subordinated to being a business scene of knowledge, ready to offer to its clients the services and certificates which they require for the labor market.[33] (p. 62, emphasis original)

Villa worries about the identity of the university and writes that:

The twenty-first-century university has an abstract identity … It represents different things. … the university in the twenty-first-century has become itself a site of dissolution of unity and the end of a singularity of discourses, identity and knowledge. It is the means and end of the blurring of boundaries.[33] (p. 61)

Also:

The University of Today could be constructing students using the reference points and values of the University of the Past. The University of the Future needs to strike a delicate balance by speaking to diverse generational and geographical power geometrics while simultaneously safeguarding academic values and standards.[28] (p. 32)

Indeed, the strong influence of market forces [1,2,3] on universities drives them toward trying to be and to do too many things, and this could be a danger for HE. Therefore, it is important to find the main roles of universities and HE in society.

4.2. Focusing on Emancipatory Competence

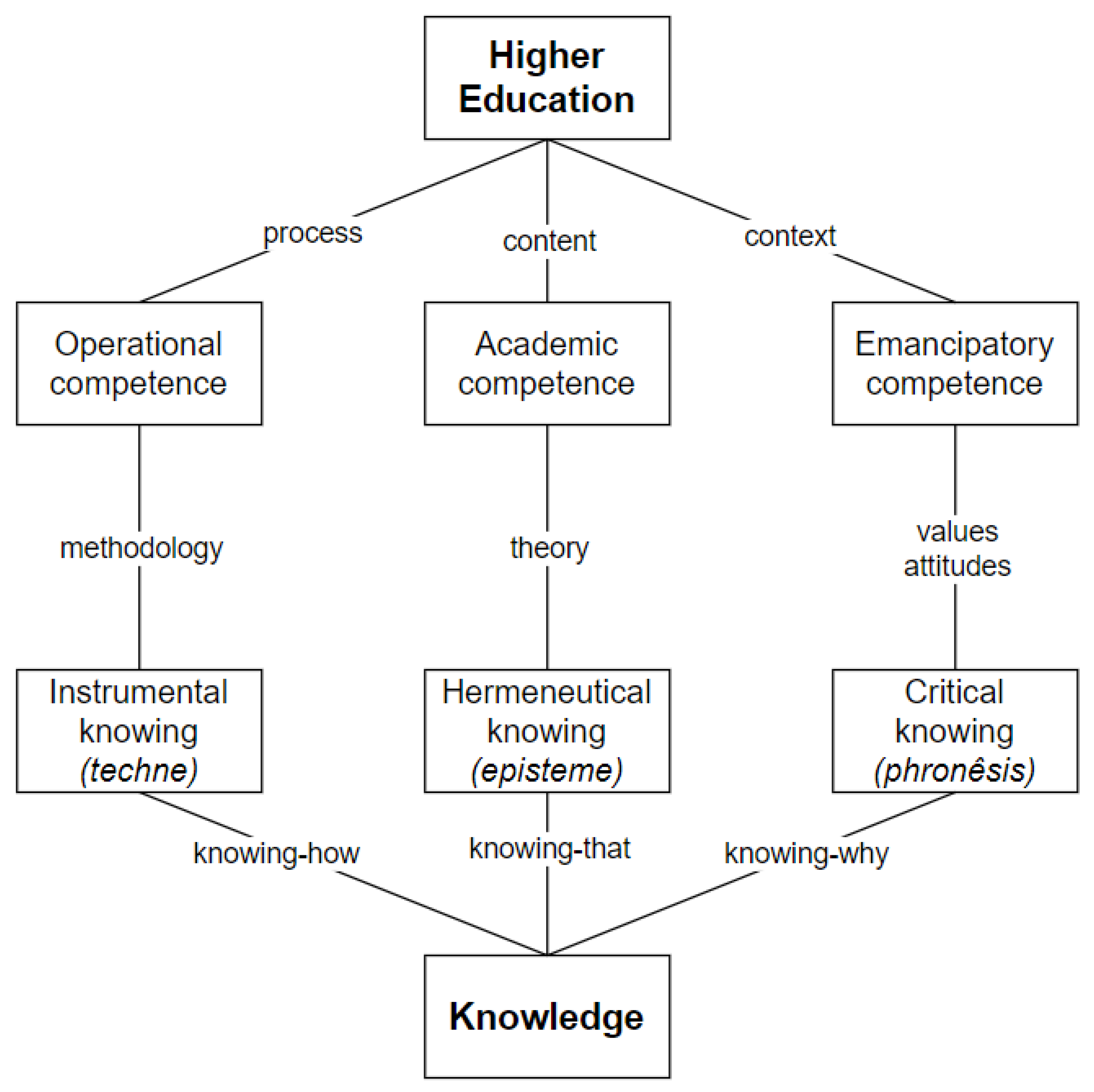

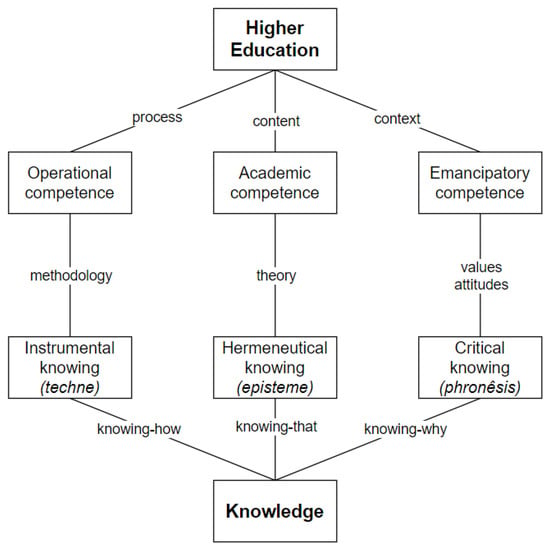

This paper argues that universities and HE should have dual roles, namely, producing useful knowledge (i.e., an epistemological goal), and educating students to be good citizens and to flourish in life (i.e., the life-world becoming of students as an ontological goal). However, these two goals (to know and to be) need to be in synthesis in HE. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship of the epistemological and ontological goals of HE. Figure 1 does not present a hierarchical relationship between these two main goals of HE because they complement each other. These two main goals are connected through three different types of knowledge (techne, episteme, and phronesis) and knowing (instrumental, hermeneutical, and critical knowing) and the three types of competences (operational, academic, and emancipatory competence) developed in HE. Instrumental knowing, that is ‘knowing how’, focuses on tacit, practical knowledge, skills, and operational competences developed by efficiently acting in the world of work. Hermeneutical or interpretative knowledge and knowing, that is ‘knowing that’, focuses on explicit knowledge, scientific, theoretical, propositional, disciplinary knowledge, and academic competences developed by being in HE. Critical, reflective knowledge and knowing, that is ‘knowing why’, focuses on values, attitude, emancipatory knowing, life-world becoming, and on applying knowledge wisely (i.e., on practical wisdom developed by a personal journey of becoming in the world of life). Habermas points out that in the process of life-world becoming “the subjects must be able to understand both themselves and their world” [34] (p. 264). He writes that:

Figure 1.

Synthesis of epistemological and ontological goals of HE (source: author).

The Interests constitutive of knowledge are linked to the functions of an ego that adapts itself to its external conditions through learning processes, is initiated into the communication system of a social life-world by means of self-formative processes, and constructs an identity.[34] (p. 315)

This paper argues that while both epistemological and ontological goals are important, in the future HE needs more focus on developing students’ emancipatory competences. Higher education needs to focus on the life-world becoming of students through cultivating their character, identity, by enhancing their capabilities to make wise judgments, to act wisely, to become good citizens, and to flourish in life. It can be achieved through the learning process, through pedagogy, and through a personalized relationship between teachers and students. Therefore, the traditional didactic triangle of content-student-teacher needs to be transformed [13]. There should be less content-oriented teaching as knowledge becomes available everywhere. In the future, HE should focus more on facilitating the students’ personal becoming, their life-world becoming process.

In brief, the followings are the main arguments for fostering students’ emancipatory competences in HE:

- We live in a world of knowledge abundancy, knowledge is widely and freely available [23,30,31].

- The world has become highly interconnected and super-complex, with wicked problems [4,5,6,7,8].

- It is hard to make judgment on what knowledge is valid and is true and what is fake and fabricated [35].

- There is a need for wisdom education, for enhancing students’ capacity to realize what is of value in life, making them capable to act with moral values and ethics [7,36].

4.3. Need for Wisdom Pedagogy in Higher Education

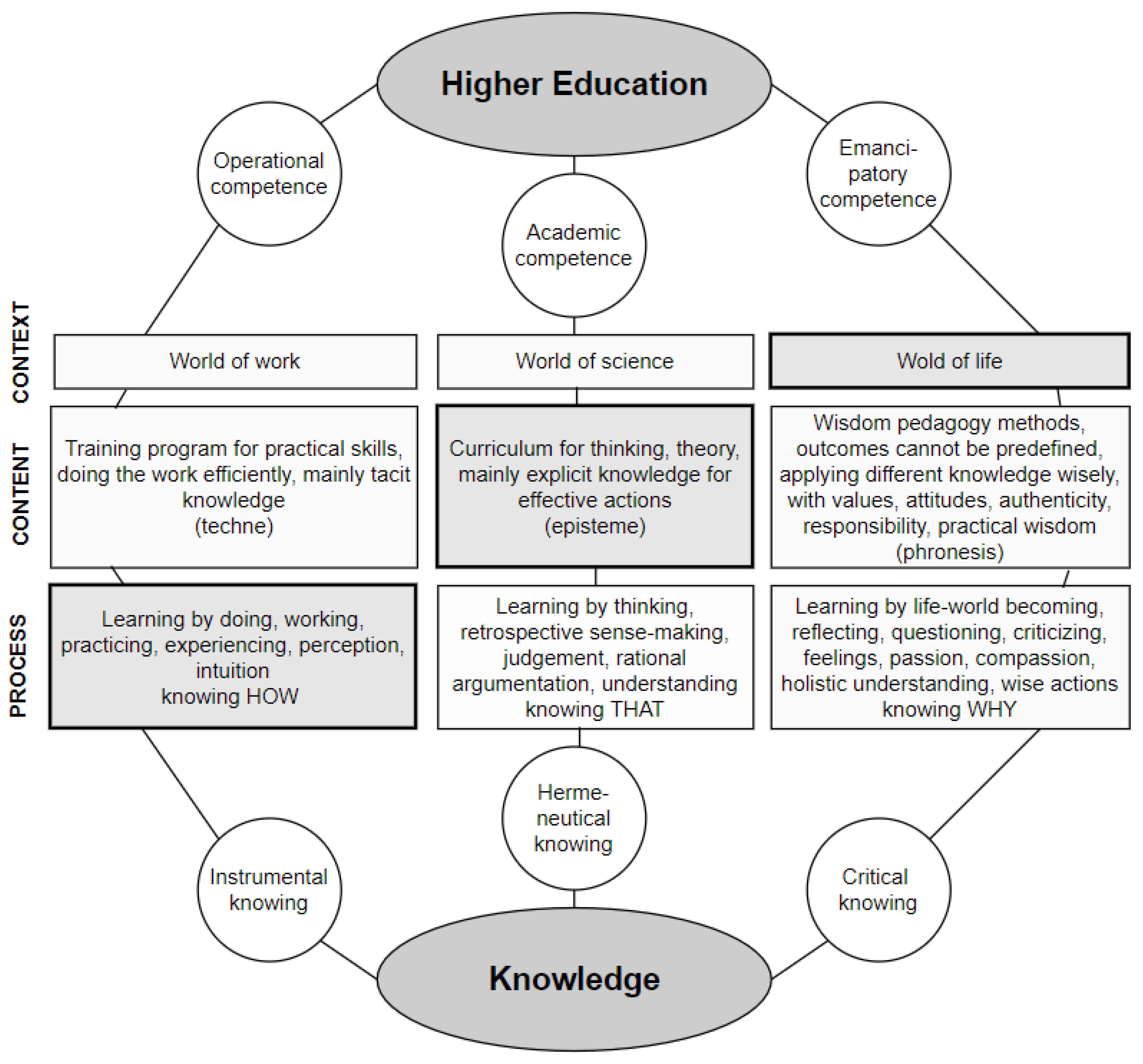

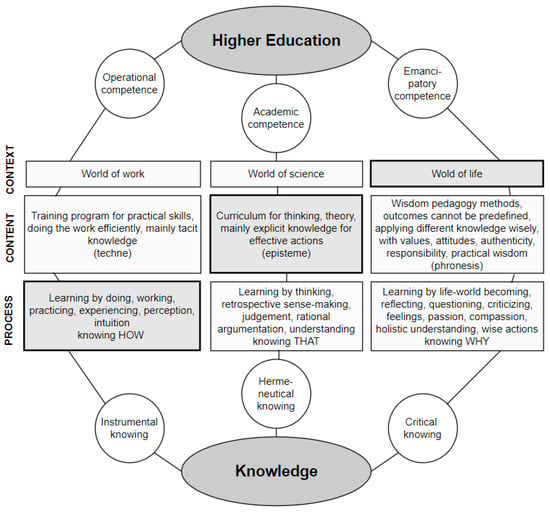

The main goal of HE is human development. The university is a place and space for networking, learning, acquiring knowledge, creating new knowledge, doing research, and developing skills and competences. Teachers and students are the main practitioners (actors) at the university. It is essential what theories, pedagogy, and approaches to learning teachers select and apply for developing the knowledge, cognitive capacities, skills, and competences of students. It is even more important how teachers shape students’ curiosity, criticality, understanding, values, attitudes, and behavior that make them successful actors in society; that is, their emancipatory competences (Figure 2). Emancipation is the core of wisdom. University pedagogy plays a direct and central role in human development, and accordingly it plays an indirect role in creating the future of the natural and social environment. Figure 2 presents the three dimensions (context, content, and process) of knowing and competences and the place of wisdom pedagogy. The focus of enhancing knowing and competences is emphasized: instrumental knowing and operational competence focus on the process; hermeneutical knowing and academic competence focus on the content, and critical knowing and emancipatory competence focus on the context.

Figure 2.

Three dimensions of knowing and competences and the place of wisdom pedagogy (source: author).

Pedagogy has different approaches regarding the age and state (physical, mental, and emotional) of learners. There is pedagogy applied for children, adults, physically challenged, and learners with different disabilities (hearing, seeing, speaking, reading, and writing difficulties; neurodevelopmental disorders; autism). Pedagogy differs also in learning different subjects (natural sciences, physics, mathematics, chemistry, management, social sciences, research, biology, etc.). Pedagogy is influenced by global challenges, culture, trends, developments, and innovations in the social and natural environment. Technological development, artificial intelligence, and robotization influence pedagogy as well. Approaches to learning could be constructivist (reversed classroom, distance assignment, and problem-based learning); collaborative (work-based learning, project-based learning, teamwork, and guest lecturers); integrative (tutorials, debates, and applying concepts and theories in practice); inquiry-based (research problems, scenarios, case studies, and role play), and reflective (discussion, feedback seminars, sharing learning experiences, and giving constructive feedback).

Can wisdom be taught? Educational scholars [5,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] argue that teaching wisdom is not easy but it is possible. Jakubik [5] presents a model of cultivating practical wisdom in education and argues that there is a new educational paradigm evolving [37]. Arlin [38] presents her developmental model of teaching. She argues that the six characteristics of a wise person (identified by Sternberg) could be applied to wise teachers: an understanding of the meaning and the limits to what is known, the search for the understanding of others’ thinking, judiciousness, understanding of ambiguity, interest in understanding what is known and what meaning to attach to it, and an appreciation of context. Bassett [39] (pp. 4–5) argues that transformative learning pedagogy could help in teaching wisdom, and she presents her emergent wisdom model and its characteristics. In this model, the cognitive, affective, active, and reflective dimensions of wisdom form a holistic system. For cultivating emancipatory competences, the active and reflective dimensions of wisdom are the most relevant ones because in teaching situations the learners need to reflect and ask questions like:

What guides my actions? To what ends are my actions directed? What means do I use? What are my values? How do I live them? Who or what is the “I” that I think I am? What am I part of?[39] (5)

Allan proposes that the educators’ primary task “should be to nurture neither learned scientists nor talented artists and artisans, but good citizens” [40] (p. 119). Others [41,42,43] discuss teaching wisdom, wisdom curriculum, and the theory of wisdom in educational settings.

What is wisdom pedagogy? Wisdom pedagogy belongs to evolutionary pedagogies. According to Gidley, we need “a more holistic, creative, multifaceted, embodied and participatory approach” [44] (p. 50) in education. Gidley, as a psychologist and educator, writes that since the year 2000, several postformal, postmodern, evolutionary pedagogies have emerged due to the ‘megatrends of the mind’. She claims that new thinking patterns, ways of knowing, and educational paradigms and approaches are having significant impacts on education. She supports “the need for the transition from formal, factory-model schooling and university education to a plurality of postformal—or evolutionary —pedagogies” because “it does not make any sense to educate in the 21st century for 19th century mindsets” [44] (p. 48). Gidley presents the 21st century evolutionary pedagogies such as: creative, social, spirituality, holistic, and integral educations, critical and postcolonial pedagogies, postmodern and poststructuralist pedagogies, aesthetic and artistic education, ecology and sustainability, imaginative education, futures and foresight, complexity education, and wisdom education [44] (p. 51). While all these evolutionary pedagogies, or a certain mix of them, could shape learners’ attitudes and values, probably the ecology, sustainability, and wisdom pedagogies are the most relevant to this paper because they call for collaboration in solving the global crises of the world [1,2,3].

Wisdom pedagogy for young children of grades 7 to 10 is discussed broadly in Malaysia [45,46]. The researchers find that the pedagogy and the methods applied had a positive influence “on students’ abilities to think and reason better … the participants demonstrated a considerable improvement in their cognitive and social-communicative skills” [45] (p. 119). In another application of the wisdom pedagogy in Malaysia, researchers find:

That when students were given an opportunity to ask questions based on the given stimulus materials and to voice out their opinions in the dialogic approach of HP (i.e., Hikmah Pedagogy, added by the author of this paper) they demonstrated the ability to reason well, think about their own thinking, and to think caringly and collaboratively. Students showed improvement in their communication skills in both languages, which was indicated by the increase in their examination results, particularly in writing and oral skills.[46] (p. 100)

While acknowledging the research results in wisdom pedagogy for children, the author of this paper calls for developing a more concise theory and a better understanding and pedagogical methods of wisdom pedagogy for adults in HE.

Teaching wisdom has been quantitatively researched for undergraduate college students by Bruya and Ardelt [47,48,49]. According to them, wisdom pedagogy is about “fostering wisdom in a formal education setting” [47] (p. 106). While this paper focuses on fostering emancipatory competence as the core of wisdom, they focus on quantifying the cognitive, reflective, and pro-social (i.e., compassion) elements of wisdom. According to them [47] (pp. 111–113) and [48] (pp. 247–248), the seven methods applied in wisdom education are:

- Challenge beliefs. Challenge students to question their own beliefs through dialogue.

- Articulate values. Prompt students to articulate their own values, weigh them against each other, and weigh them against the values of others in the community, including the common good.

- Self-development. Self-development in terms of wisdom means improving a variety of abilities, including comfort with ambiguity, perspective-taking, virtues, and moral emotions.

- Self-reflection. This involves thinking about how the values and beliefs presented in the subject matter of the class may be applicable to the student’s own past, present, and future life experience.

- Groom the emotional aspect of moral values. Consider the perspectives of others through scenarios that arouse empathy and through reflective or meditative exercises on moral emotions, such as gratitude and compassion.

- Read texts. Use textual aids to supply perspectives, principles, frameworks, and vocabulary (narratives to engage the moral imagination), to cultivate moral emotional sensitivity, and to prompt perspective taking; didactic and speculative philosophical texts to provide examples of principles to live by and frameworks for the exploration of interconnected beliefs about the world; guidance from the instructor: supply the vocabulary (hence, concepts) that students need to make sophisticated, nuanced distinctions about their values and beliefs.

- Foster a community of inquiry in which all participants (students and teacher) are mutually supportive and committed to the pursuit of understanding and self-improvement.

These seven educational methods for teaching wisdom correspond with the theory of Bildung [10,12,13,14,18,19] discussed in Section 2 of this paper. Therefore, learning from the past becomes important for the future. Furthermore, methods of wisdom education are in line with Habermas’ [34] and Barnett’s [50] (pp. 172–186) concepts of life-world becoming (i.e., emancipatory competence) (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Barnett summarizes the implications of life-world becoming for HE. He underlines the importance of encouraging reflections and reinterpretations, conducting open dialogue and discourse, being sensitive to the claims of others, questioning the rules, being skeptical, developing arguments, advocating continuous learning, testing the validity of arguments, including ethical evaluations of arguments, and taking a broader view and exploring broader implications of arguments and actions on others, society, and on nature [50] (p. 185).

In brief, this section of the paper discussed the possible future trends and the need for wisdom pedagogy in HE by looking forward. Both the epistemological and ontological goals of HE in human development were presented in synthesis (Figure 1). Beside operational and academic competences, the need for wisdom and developing emancipatory competences in HE was emphasized (Figure 2). Concurring with Bruya and Ardelt, “as society becomes increasingly complex, the need to foster wisdom in our future citizens and leaders becomes increasingly urgent” [48] (p. 249). Although wisdom research has flourished since the 1980s in philosophy, psychology, and management sciences, it would need more understanding of how emancipatory competences and wisdom could be fostered in HE with wisdom pedagogy.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to cultivate the future in HE, first, by looking backward and learning from the past, then, looking around by questioning the present trends, and finally, looking forward by imagining the future of HE. This paper sought to answer the question how HE can foster students’ life-world becoming and emancipatory competences with wisdom pedagogy.

This paper has several limitations because it builds on a limited number of literature sources, a few authors’ ideas have received more attention and others were ignored, and the paper lacks empirical justifications. These limitations, however, open several opportunities for further research. Educational researchers could explore the literature further. For example, studying the views of the French philosophers like Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida would enrich the findings and improve the understanding of wisdom pedagogy and the role of universities. Derrida put it clearly why universities exist and what roles they play in society. He argued that universities exist:

to tell the truth, judge, to criticize in the most rigorous sense of the term, namely to discern and decide between the true and the false; and it is also entitled to decide between the just and the unjust, the moral and the immoral, this is so insofar as reason and freedom of judgment are implicated in it as well.[51] (p. 97, emphasis original)

Further research could compare the educational implementations of the Bildung concept in different countries and regions. Exploring and developing teachers’ educational practices in teaching wisdom are exciting research areas as well. Developing new pedagogical methods to teach wisdom, and creating new models of wisdom pedagogy together with practitioners and then testing them offer plenty of opportunities for research. Exploring a more altruistic way of developing moral and ethical values in others, and cultivating the future in HE in a way that would lead to good citizens and to a better world in the future need more attention in educational research. Furthermore, the author of this conceptual paper calls for more discussions, critical views, debates, comments, and suggestions about wisdom pedagogy, the tasks of HE, and about the roles and place of the university in society.

To conclude, learning from the past, exploring the concept of Bildung of the 18th century, is useful when thinking and rethinking the future tasks of HE in our super complex environment full of global challenges and wicked problems to be solved [1,2,3]. The findings demonstrate the need for enhancing altruistic thinking in HE and for cultivating students’ life-world becoming. Russell [52] (pp. 175–176) asked if wisdom can be taught and if teaching wisdom should be one of the aims of education, and he answered both of these questions positively. Concurring with him, this paper argued that “the world needs wisdom as it has never needed it before, and if knowledge continues to increase, the world will need wisdom in the future even more than it does now” [52] (p. 177).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks participants for their supporting and valuable comments on her presentation of some of the ideas included in this paper at the Philosophy and Theory of Higher Education Conference (PHEC), ‘University under Siege?’ at Uppsala University, Sweden, 7–9 June 2022. The author appreciates the insightful comments of Professor Hans Georg Schaathun, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Department of ICT and Natural Sciences. In addition, special thanks go to anonymous reviewers who, with their thoughtful and helpful comments, improved the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- World Economic Forum (WEF). The Davos Agenda 17–21 January 2022. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/01/the-davos-agenda-2022-addressing-the-state-of-the-world/ (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- World Economic Forum (WEF). The Global Risks Report 2021. 16th Edition. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2021.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- World Economic Forum (WEF). The Global Risks Report 2022. 17th Edition. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2022.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Australian Public Service Commission (APSC). Tackling Wicked Problems. A Public Policy Perspective. 2007. Available online: https://legacy.apsc.gov.au/tackling-wicked-problems-public-policy-perspective (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Jakubik, M. Educating for the Future–Cultivating Practical Wisdom in Education. JSCI 2020, 18, 50–54. Available online: https://www.iiisci.org/journal/sci/FullText.asp?var=&id=SA422DQ20 (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Lehtonen, A.; Salonen, A.; Cantell, H.; Riuttanen, L. A pedagogy of interconnectedness for encountering climate change as a wicked sustainability problem. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, N. The World Crisis–and What to Do about it: A Revolution for thought and Action, 1st ed.; World Scientific Publishing Company: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Willamo, R.; Helenius, L.; Holmström, C.; Haapanen, L.; Sandström, V.; Huotari, E.; Kaarre, K.; Värre, U.; Nuotiomäki, A.; Happonen, J.; et al. Learning how to understand complexity and deal with sustainability challenges–A framework for a comprehensive approach and its application in university education. Ecol. Model. 2018, 370, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A. The German Tradition of Self-Cultivation (Bildung) and Its Historical Meaning. Porto Alegre. Educ. Real. 2019, 44, 1–18. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/edreal/a/HLLcPFh84zpNNdDrrvnBWvb/?format=pdf&lang=en (accessed on 22 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bohlin, H. Bildung and Moral Self-Cultivation in Higher Education: What Does It Mean and How Can It be Achieved? In Forum on Public Policy; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 57–61. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1099530 (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Lindskog, M. —Bildning, vetenskaplighet och högskolemässig utbildning: En textanalys‖ (―Bildung, scientific thinking and university-level education. A textual analysis). Candidate Thesis, Stockholm Institute of Education/Department of Didactic Science and Early Childhood Education, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 2007. Available online: https://www.uppsatser.se/uppsats/35f5683d63/ (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Lumsden, S. The Role of Bildung in Hegel’s Philosophy of History. Intellect. Hist. Rev. 2021, 31, 445–462. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354018128_The_role_of_Bildung_in_Hegel’s_philosophy_of_history (accessed on 12 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y. Wilhelm von Humboldt’s Bildung theory and educational reform: Reconstructing Bildung as a pedagogical concept. J. Curric. Stud. 2021, 54, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, J.; Eilks, I. The Bildung Theory—From von Humboldt to Klafki and Beyond. In Science Education in Theory and Practice; Akpan, B., Kennedy, T.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herder, J.G. Philosophical Writings; Forster, M.N., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Port Chester, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Runes, D.D. (Ed.) Dictionary of Philosophy; Littlefield, Adams & Co.: Totowa, NJ, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Durant, W. The Story of Philosophy. The Lives and Opinions of the Greater Philosophers; The Pocket Library: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, H.-G. Truth and Method, 2nd ed.; Sheed & Ward: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Humboldt, W. Theory of Bildung (Theorie der Bildung des Menschens). In Teaching as a Reflective Practice: The German Didaktik Tradition; Westbury, I., Hopmann, S., Riquarts, K., Eds.; Studies in Curriculum Theory Series; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- A Call for Accountability and Action. The Deloitte Global 2021 Millennial and Gen Z Survey. 2021. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/millennialsurvey.html (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Democracy Report 2022. Autocratization Changing Nature? V-Dem Institute at the University of Gothenburg, March 2022. Available online: https://v-dem.net/media/publications/dr_2022.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Kinzelbach, K.; Pelke, L. Academic Freedom Index. March 2022. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lars-Pelke/publication/358978180_Academic_Freedom_Index_Update_2022/links/62208d7ae474e407ea1eb567/Academic-Freedom-Index-Update-2022.pdf?origin=publication_detail (accessed on 22 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. The Space of Flows. In The Rise of the Network Society. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture; Castells, M., Ed.; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 376–428. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, R. The Idea of Ecology. In The Ecological University. A Feasible Utopia; Barnett, R., Ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2018; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, R. Seven Ecosystems. In The Ecological University. A Feasible Utopia; Barnett, R., Ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2018; pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, R. The Philosophy of Higher Education. A Critical Introduction; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, D. The University as Fool. In The Future University. Ideas and Possibilities; Barnett, R., Ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, L. Imagining the University of the Future. In The Future University. Ideas and Possibilities; Barnett, R., Ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, R. The Learning Society? In The Limits of Competence. Knowledge, Higher Education and Society; The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1994; pp. 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, A. Researching the Future University. HE Education Research Census, 15 June 2022. Available online: https://edu-research.uk/2022/06/15/researching-the-future-university/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Matthews, A.; Kotzee, B. Bundled or unbundled? A multi-text corpus-assisted discourse analysis of the relationship between teaching and research in UK universities. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 48, 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCowan, T. Higher education, unbundling, and the end of the university as we know it. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2017, 43, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.D. The Idea of the University in Latin America in the Twenty-First Century. In The Future University. Ideas and Possibilities; Barnett, R., Ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Knowledge and Human Interests; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, S. What should remain once the great academic reset comes? In Proceedings of the Keynote speech at the 4th Annual Philosophy and Theory of Higher Education Conference (PHEC) “Universities under Siege?”, 7–9 June 2022, Uppsala Sweden.

- Maxwell, N. Creating a Better World. Toward the University of Wisdom. In The Future University. Ideas and Possibilities; Barnett, R., Ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubik, M. Quo Vadis Educatio? Emergence of a New Educational Paradigm. J. Syst. Cybern. Inform. 2020, 18, 7–15. Available online: http://www.iiisci.org/journal/sci/FullText.asp?var=&id=CK208UT20 (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Arlin, P.K. The wise teacher: A developmental model of teaching. Theory Pract. 1999, 38, 12–17. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1477202 (accessed on 4 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bassett, C. Wisdom in three acts: Using transformative learning to teach for wisdom. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Transformative Learning Conference, East Lansing, MI, USA, 6–9 October 2005; Available online: https://www.wisdominst.org/WisdomInThreeActs.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Allan, G. The Conversation of a University. In Contemporary Philosophical Proposals for the University: Toward a Philosophy of Higher Education; Stoller, A., Kramer, E., Eds.; Palgrave, MacMillan, Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, T. Teaching for wisdom encounter. Educ. Mean. Soc. Justice 2001, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.G.; Kesson, K.R. Curriculum Wisdom: Educational Decisions in Democratic Societies; Pearson Education Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J. Why schools should teach for wisdom: The balance theory of wisdom in educational settings. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 36, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidley, J.M. Evolution of education: From weak signals to rich imaginaries of educational futures. Futures 2012, 44, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, R.; Hussien, S.; Imran, A.M. Ḥikmah (Wisdom) Pedagogy and Students’ Thinking and Reasoning Abilities. Intellectual Discourse. 2014, Volume 22. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289106151_Hikmah_wisdom_pedagogy_and_students’_thinking_and_reasoning_abilities (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Yusoffi, W.M.W.; Hashim, R.; Khalid, M.; Hussien, S.; Kamalludeen, R. The Impact of Hikmah (Wisdom) Pedagogy on 21st Century Skills of Selected Primary and Secondary School Students in Gombak District Selangor Malaysia. J. Educ. Learn. 2018, 7, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruya, B.; Ardelt, M. Wisdom can be taught. A proof-of-concept study for fostering wisdom in the classroom. Learn. Instr. 2018, 58, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruya, B.; Ardelt, M. Fostering Wisdom in the Classroom. A General Theory of Wisdom Pedagogy. Teach. Philos. 2018, 41, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelt, M.; Bruya, B. Three-Dimensional Wisdom and Perceived Stress among College Students. J. Adult Dev. 2020, 28, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R. The Limits of Competence. Knowledge, Higher Education and Society; The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, J. Eye of the University: Right to Philosophy 2; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, B. Knowledge and Wisdom. In Portraits from Memory and Other Essays; Russell, B., Ed.; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1956; pp. 173–177. Available online: https://archive.org/details/portraitsfrommem005918mbp/page/n177/mode/2up?view=theater&q=wisdom (accessed on 29 August 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).