Abstract

Video-sharing platforms have significantly influenced social justice movements by creating unprecedented opportunities for mobilization and support. However, YouTube’s unique role and platform culture in facilitating social justice movements remain relatively understudied. This research addresses this gap by analyzing video content related to two prominent online social justice movements: #BLM and #StopAAPIHate. We conducted a comprehensive thematic analysis of a dataset comprising 489 videos obtained using the YouTube Data API. Thematic categories were developed to explore the identities of video creators, the type of information conveyed, storytelling techniques, and promotional features utilized. Our findings indicate that public figures, vloggers, and news reporters are the most frequent creators of videos supporting these movements. The primary purpose of these videos is to share movement-related knowledge and personal stories of discrimination. Most creators primarily promote their social media accounts and do not extensively utilize platform features such as live streaming, merchandise sales, donation requests, or sponsorships to actively support these social justice initiatives.

1. Introduction

Online platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter have evolved into essential tools for social justice movements, providing opportunities for mobilization and support. While involvement in social movements has historically centered on protests, riots, financial contributions, and other direct actions, social media is increasingly recognized as a crucial medium for scaling social movements [1,2,3]. Various forms of social media now allow movements to rally public support across major platforms like Twitter and Facebook [4]. YouTube, a video-sharing platform, has particularly amplified the potential for social justice movements to reach huge audiences [5]. Moreover, the video medium has generally shown to be highly persuasive [6]. YouTube, in particular, provides multiple ways to cultivate connections to the public. For example, creators often use charismatic speech [7] or a talking-to-camera setup to create a feeling of direct communication with the audience [8]. Furthermore, the platform facilitates greater interactivity between creators and their viewers through features like likes, comments, and subscriptions. Such interactivity can be crucial in fostering a sense of shared identity and solidarity, which can, in turn, encourage movement participation [9]. In this work, we are motivated by a desire to understand YouTube’s distinct role in advancing social justice movements. Despite the recent rise and prominence of online activism movements on YouTube, there remains limited understanding of who the key stakeholders leveraging this emerging medium are, how racial discourse is presented and framed, and how YouTube’s platform features facilitate audience engagement. Prior studies have largely concentrated on YouTube’s role in spreading activist messages [2,3,10], yet there is insufficient insight into how the content creation and utilization of platform-specific features can be effectively supported for social movements and communities.

This study addresses this gap by analyzing video content related to two prominent online social justice movements: Black Lives Matter (BLM) and Stop Asian American and Pacific Islander Hate (StopAAPIHate). Started in 2013, the BLM movement advocates for the eradication of systemic racism and violence against Black individuals, aiming to combat white supremacy, empower Black communities, and promote Black creativity and joy. The StopAAPIHate movement, founded in 2020, addresses the surge in racism, xenophobia, and violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs), focusing on raising awareness, policy advocacy, and solidarity among marginalized groups.

To understand these two movements on YouTube, we adopt Kitts’ theory [9], which emphasizes studying the microstructures that frame social movements, including identity, information, and exchange methods. We analyzed a dataset comprising 489 videos featuring the hashtags #BLM or #StopAAPIHate, developing thematic categories through thematic analysis. These categories encompassed elements such as the identities of video creators, the nature of information conveyed, storytelling techniques employed, and types of audience interaction encouraged. This research addresses three primary questions:

- RQ1

- Who are the speakers or presenters featured in YouTube #BLM and #StopAAPIHate videos?

- RQ2

- What information is conveyed in YouTube #BLM and #StopAAPIHate videos, and what storytelling techniques are employed?

- RQ3

- Which video-sharing features do content creators commonly utilize to engage and interact with viewers?

The analysis revealed diverse identities among video creators, including artists, religious leaders, public figures, news reporters, ordinary individuals, and vloggers. Public figures and vloggers emerged as the two most prominent categories among these creators. The content of these videos covered topics such as educating viewers about social movements, discrimination against minorities, criticism of movements, coverage of protests, and artistic showcases, with discrimination being the most common topic. Storytelling styles varied from informational and artistic to conversational and promotional, with conversational videos being the most common. Audience engagement methods included interacting on the platform, donating, joining live streams, sponsorships, buying merchandise, and participating on social media. However, nearly half of the videos did not explicitly encourage viewers to interact in any specific way.

Our research provides an intricate typology of social movements on YouTube, encapsulating crucial communication functions pivotal to movements like #BLM and #StopAAPIHate. This typology is shaped by YouTube’s unique affordances and cultural context. Content creators and activists leverage the platform to engage audiences in social discourses through talk-to-camera conversations that convey information in a parasocial manner. Despite a focus on discrimination, creators often shy away from fully utilizing YouTube’s interactive features, such as live streaming, donations, and merchandise sales. This suggests a need for additional mechanisms to boost audience engagement in social movements.

2. Related Work

2.1. Social Movements and Social Media

While social media has long been a tool for social movements, its significance grew during the pandemic as a virtual means of disseminating information and rallying support. Movements like Black Lives Matter (BLM) and Stop AAPI Hate relied heavily on these platforms to amplify their voices. Both anti-racist movements arose in response to specific incidents of racism and violence. The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was first used in 2013 following the acquittal of a police officer involved in the fatal shooting of a Black teenager [11]. Similarly, #StopAAPIHate gained prominence in 2021 following a mass shooting in Atlanta, where the majority of victims were of Asian descent. Notably, this event took place during the pandemic, a period marked by a sharp increase in anti-Asian hate crimes. Although the two movements emerged at different times and addressed the needs of distinct communities, both shared a common purpose: raising awareness about systemic racism and oppression.

Consequently, numerous studies have focused on these two movements to understand social media’s role. Most research has centered on Facebook and Twitter, where researchers performed text-based analyses to explore social movement-related content (e.g., [12,13,14,15]). These studies uncovered common themes, such as raising awareness, spreading information, denouncing racism, recounting discriminatory experiences, and calling for action [13,14].

However, critical differences emerged in the discussions specific to each movement. For instance, users were more inclined to share stories of racial discrimination for StopAAPIHate than for BLM [16]. Unique topics also arose: pandemic-related stigma for StopAAPIHate and police brutality for BLM [17]. These variations reflect the different objectives and timelines of the movements, with BLM being more established compared to the relatively new StopAAPIHate. Research following a hate incident on Twitter highlighted how focus shifted over a week from awareness to calls for action and, finally, solidarity with the AAPI community [13]. Thus, topics evolve based on each movement’s maturity and duration.

Most studies emphasize post content over user identity, often categorizing posters simply as Twitter or Facebook users. Some studies identify political leanings [12], while others distinguish between supporters and non-supporters. Limited studies have explored how influencers approach social movements, often finding that influencers primarily share resources and raise awareness through infographics to maintain credibility among followers [18]. Their influence is notable; a study on BTS fans showed how their commitment to BLM was tied to the band’s own dedication to the cause [19]. This indicates that influencers have strong community ties, making it essential to understand their role and strategies in social justice movements. Moreover, little research has examined whether disclosing user identity affects mobilization and movement propagation.

Audience interaction features are another key aspect in social justice movement research [20]. These include likes, shares, comments, and platform-specific features. They amplify posts and initiate discussions crucial for a social movement’s growth [20]. Interviews with BLM members highlighted the importance of such features in establishing a strong online presence, which aids resource mobilization and narrative control [1]. Thus, understanding how these features can enhance social movements is vital. The literature on social movements and social media has primarily focused on text-based platforms, overlooking the value of video-sharing platforms like YouTube and TikTok. Future research must recognize the contributions of these visual platforms in advancing social justice movements.

2.2. YouTube Culture and Social Movements

YouTube is a video-sharing platform that emerged in 2005 and has grown tremendously since then [21]. The platform hosts a wide range of videos and creators, enabling both professionals, such as news reporters, and “amateurs” to upload content on the same platform [22]. The availability of user-generated content has been particularly valuable for activism and social movements, fostering “citizen journalism” as an alternative to traditional news reporting [21]. For example, a content analysis of YouTube videos about the Occupy Wall Street movement—a social movement against socio-economic inequality—found that the vast majority of videos were original, using little to no content from other sources. Additionally, almost 30% of the videos included protest footage [10]. In contrast to traditional movements, YouTube empowers grassroots activists to produce and disseminate their narratives directly to the public, independent of mainstream media channels [2,3].

YouTube houses several “micro-celebrities” or influencers on its platform, more commonly known as YouTubers [23,24]. Although entertainment is one of YouTube’s most popular video categories [21], video creators have found ways to blend entertainment with activism. For instance, Knupfer et al. found that when participants engaged with influencers, on Instagram and/or YouTube, who discussed environmental activism, the participants were more likely to participate in low- and high-effort environmental activism [25]. Another study exploring political parody videos found that when participants perceived that a video had a greater influence on others, the participants themselves were more likely to engage in social media activism [26]. The impact of such videos could be due to several factors—one being the general persuasive nature of video media [6]. However, factors specific to YouTube also play a significant role. Studies suggest that YouTube creators might employ strategies such as using charismatic speech [7] or a talk-to-camera setup to create the feeling of speaking to the viewer [8]. Personability is also a crucial element in videos where creators share their personal experiences with the crises [27]. This element of personability could be a facet of a larger phenomenon known as parasocial interactions. YouTube features such as liking, commenting, subscribing, etc., enable interaction between influencers and their audience members [28]. Therefore, unlike traditional movements, these online features allow influencers from different geographic locations to participate in social movements virtually and join the same movements at the same time [2].

Video creators’ interactions with viewers are one-sided from the audience’s perspective. This type of interaction may feel similar to a social experience in real life. The feeling of “mutual awareness” between the audience and creators is termed parasocial interaction (PSI). Despite their illusory nature, studies have found that PSIs can have significant psychological impacts on individuals in various ways [29]. Moyer-Gusé postulates that PSIs can alter perceived norms because the media figure can set an example for their audience to break away from societal norms [30]. Research supports this proposition by showing that PSIs can influence attitudes. For instance, a study examining purchase intentions found that PSIs had a positive relationship with influencers’ perceived credibility and informational influence, i.e., audience adoption of information suggested by influencers [31]. Similarly, a meta-analysis found a significant correlation between PSIs and persuasive outcomes [32]. However, despite preliminary research suggesting the relevance of these factors in movement propagation, little is known about who uses social media videos to inspire action in social movements and how these videos engage viewers.

2.3. Understanding Social Movements on YouTube

One way social movements have traditionally been conceptualized is through resource mobilization theory. Resource mobilization is the process of securing resources needed for collective action [33]. Although participation in social movements has traditionally been associated with actions like protests, riots, financial support, or other calls to action, social media is increasingly seen as a crucial venue for scaling social movements [1]. Social movements can now use various forms of social media to mobilize the public on major platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube [4]. For example, during the Egyptian revolution, activists used Twitter and Facebook to gain international attention and increase available resources [34]. In the U.S., social media supports collective public actions like electing officials, funding campaigns, attending political events, and volunteering for campaigns [35]. However, the social movement resources provided by video-sharing platforms like YouTube remain underexplored. How activists encourage movement participation through YouTube can be analyzed using a framework identified by Kitts [9], which includes three main perspectives: identity, information, and exchange.

The expression of identity encourages movement participation by fostering solidarity among activists [9]. Creating a shared identity helps unite people within a collective toward a common goal, and social media facilitates this by providing a “cyberplace” where individuals with shared identities can connect [2]. Social media users can then recruit others by sharing, liking, or interacting with posts about social movements [36]. This approach revolutionizes the traditional concept of participation in social movements [2]. While platforms like Twitter and Facebook excel in information sharing, they often struggle to build a strong, shared identity. In contrast, YouTube uniquely fosters user interaction through video content [37]. Video creators can use talk-to-camera communication to become more relatable, revealing their identities while disseminating information and mobilizing support.

The information approach involves sharing and disseminating movement-related information, facilitating participants’ ability to mobilize resources and take collective action. While this approach is common across social media, YouTube provides a unique video-based platform where both professional and amateur creators can produce news content accompanied by personal commentary [22]. By enabling professional and amateur content to coexist and recommending videos through its “related videos” feature, YouTube decentralizes news dissemination [38]. However, prior research has predominantly focused on examining YouTube’s emerging role as a technological platform supporting social movements [2,3,39], or analyzing social networks formed around these movements on the platform [40]. Little attention has been given to understanding content creators’ perspectives, specifically regarding the type of information they aim to convey and the storytelling techniques they employ to deliver their messages.

The exchange approach is crucial in encouraging movement members to act through social incentives, such as social approval. Social exchange can also manifest itself as punishments for non-participation. This phenomenon of encouraging or discouraging participation through rewards or punishments has been studied on YouTube. Multiple studies indicate that viewers are easily influenced to participate in movements by YouTube activists [25,26]. Additionally, features like YouTube live streaming, donation boxes, and merchandise are valuable tools for social exchange and securing financial support for movements. A study analyzing reactions to YouTube videos of the police shooting of Oscar Grant found that comments were largely negative, criticizing the video quality or bystanders’ inaction, or positive, expressing gratitude for recording the incident and calling for action. This range of comments discourages bystander behavior while encouraging videographers to document hate incidents [41]. Therefore, it is crucial to explore whether and how video creators use the YouTube platform to support movements.

Viewing YouTube through the lens of resource mobilization reveals its vast potential for mobilization and movement propagation. Increasingly, diverse and participatory media are powerful agents of social change, challenging the dominance of once exclusive mainstream news media [42]. Despite this potential, YouTube remains understudied in the literature, leaving a gap in understanding how social movements disseminate information and gain traction on the platform. To address this gap, this study conducts a content analysis of YouTube videos related to two prominent online social justice movements: #BlackLivesMatter and #StopAAPIHate.

3. Data Collection and Analysis Method

Videos were collected using the YouTube Data API with the keywords #BLM and #StopAAPIHate. The initial data collection yielded 1548 videos, consisting of 1250 videos related to #BLM and 298 videos related to #StopAAPIHate. The hashtags had to appear either in the video title, description, or video tags. The video data were collected in June 2022 and included videos published between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2021. We observed an unequal representation of the two movements on the YouTube platform. To address this imbalance and reduce potential biases toward any specific movement, we randomly selected 298 videos from the #BLM sample to match the number of #StopAAPIHate videos, resulting in a balanced dataset of 596 videos. This approach also reduced the video number in the manual verification process. We used a computer program to identify and remove duplicate videos, after which two researchers manually verified and excluded videos containing unrelated content. Following these steps, the final dataset comprised 489 unique videos.

To gain an initial understanding of how the videos reflect the identity, information, and exchange frames described in [9], we annotated 150 randomly selected videos by examining aspects such as the information conveyed, presentation style, and viewer interaction. This sample facilitated the development and validation of a codebook through thematic analysis [43]. Of these videos, 60 were used for codebook development, and the remaining 90 were utilized for validation.

The thematic analysis process consisted of several phases: data familiarization, generating initial codes, subtheme searching, theme reviewing, and finalizing themes. During the data familiarization and initial code generation phases, the two authors examined 60 videos (30 each) to identify video topics and develop initial annotations related to the creators’ identity, information and storytelling techniques, and audience interaction. In the theme searching phase, the authors used affinity diagramming to group emerging subthemes and generate an initial coding framework. During subtheme reviewing and finalization, the initial code was applied to three rounds of 30 videos each (90 videos total). After each round, the authors discussed potential adjustments to refine and update the code definitions. The finalized subthemes are presented in Table 1. By the final round, the authors achieved substantial inter-rater reliability across all categories, measured using Krippendorf’s alpha: information (), storytelling (), informational subthemes (), artistic subthemes (), conversational subthemes (), identity (), interaction (), addressing (), self-disclosure (), PSI level (), and number of people (). Using the finalized coding framework, the authors annotated the remaining videos. After excluding unrelated content, the final analytic sample included 489 videos, comprising 266 #BLM videos, 210 #StopAAPIHate videos, and 13 videos addressing both movements.

Table 1.

The codebook identified through thematic analysis according to [9] includes themes related to identity, information, storytelling, and interaction.

4. Results

4.1. RQ1: Video Figure Types

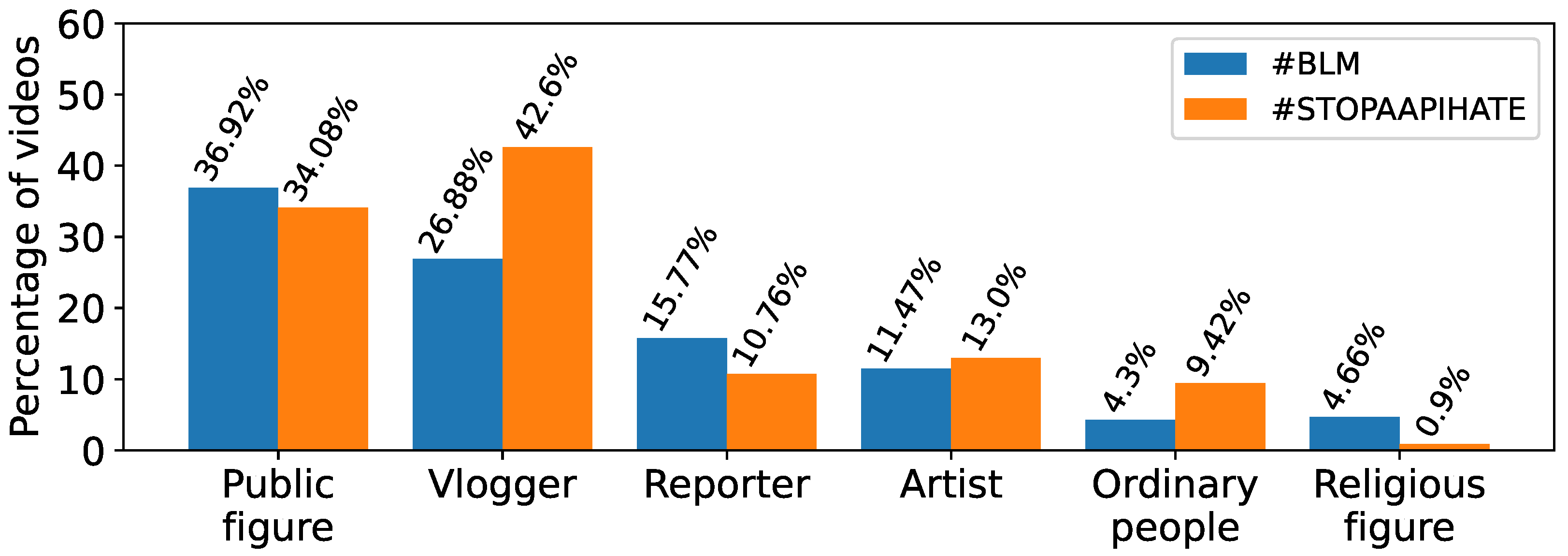

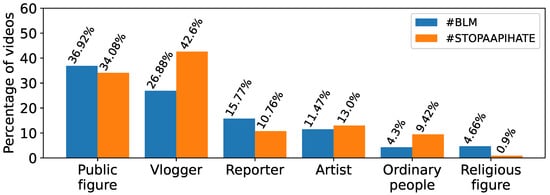

The identities in the sampled videos included public and professional personalities, vloggers, news reporters, artists, ordinary individuals, and religious figures, listed in descending order based on their prevalence in the videos (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Identity subtheme distribution, ordered by descending percentage of videos.

Public figures emerged as the most common identity, comprising 36.20% ( ) of all sampled videos. The distribution of these videos was similar across both movements, with 36.92% of #BLM videos and 34.08% of #StopAAPIHate videos featuring public figures. These identities included creators who identified themselves as having public or professional roles, such as activists and professors. For example, the video “At the Black Lives Matter Protests in New York | 2020” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LLDXJahtgBA (accessed on 31 December 2024)) shows clips from various #BLM protests in New York, featuring activists speaking publicly at these events. Another video titled “The Internment of Japanese Americans with Dr. Karen Korematsu, Series on the US & China (Week 2/9)” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9bv9OtQi5sc (accessed on 31 December 2024)) depicts an activist delivering a Zoom presentation on Japanese internment in America.

Vloggers were the second most prevalent identity across both movements, accounting for 33.54% () of all videos. Creators with this identity typically produce commentary videos or casually share aspects of their everyday lives with viewers. In particular, 42.60% of #StopAAPIHate videos and 26.88% of #BLM videos featured vloggers. These individuals, often influencers or content creators such as vloggers or podcasters, typically lead solo or group discussions to express their views on social movements. For example, in the video “S01E21-Racism in Sports-BLACK LIVES MATTER | SAY NO TO RACISM | Everybody is Equal | KICK IT OUT” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zdsyl0pNf0o (accessed on 31 December 2024)), vloggers discuss racism in sports. In another video, “Love All | #StopAsianHate” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mbr91ERhcPk (accessed on 31 December 2024)), a creator is showcased promoting love and raising awareness for #StopAAPIHate.

The least frequent identities in the video sample were artists, ordinary people, and religious figures. Artists are creators whose channels primarily focus on sharing various forms of art. This identity accounts for 11.66% () of the sample and includes videos such as “Students unveil Black Lives Matter mural on campus” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tnduDAl_Qsw (accessed on 31 December 2024)) and “Heavy Lag-‘Stop AAPI Hate’ Benefit Livestream Set (5/1/21)” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W9zLc2u7PMU (accessed on 31 December 2024)). The former presents a campus mural supporting #BLM, while the latter features a band’s musical performance aimed at fundraising for #StopAAPIHate. Ordinary people are individuals featured in videos who do not appear to hold professional roles or maintain active YouTube channels. Constituting 6.55% () of the sample, they appeared in videos such as “Black Lives Matter 13 Guiding Principles” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t5COVzi1q64 (accessed on 31 December 2024)), in which deaf students use sign language to discuss the principles of #BLM, and “‘Hero, Highlight, Hardship’ | LOHS Asian American Student Union Talks with Coach Cho” ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oCZifT-9Un0 (accessed on 31 December 2024)), where a coach engages Asian American students in conversations about their personal experiences. Religious figures are creators whose videos take place within religious settings, such as worship services or sermons. This identity was the least represented, accounting for 3.07% () of the sample. Examples include “Black Lives Matter & Other Race Issues (10AM)” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-E1o0N-zecU (accessed on 31 December 2024)) and “A Catholic Response to Anti-AAPI Hate” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ymKmnxe6f8 (accessed on 31 December 2024)), where religious leaders discuss social justice issues from the perspective of their faith.

4.2. RQ2: Video Information

4.2.1. Information

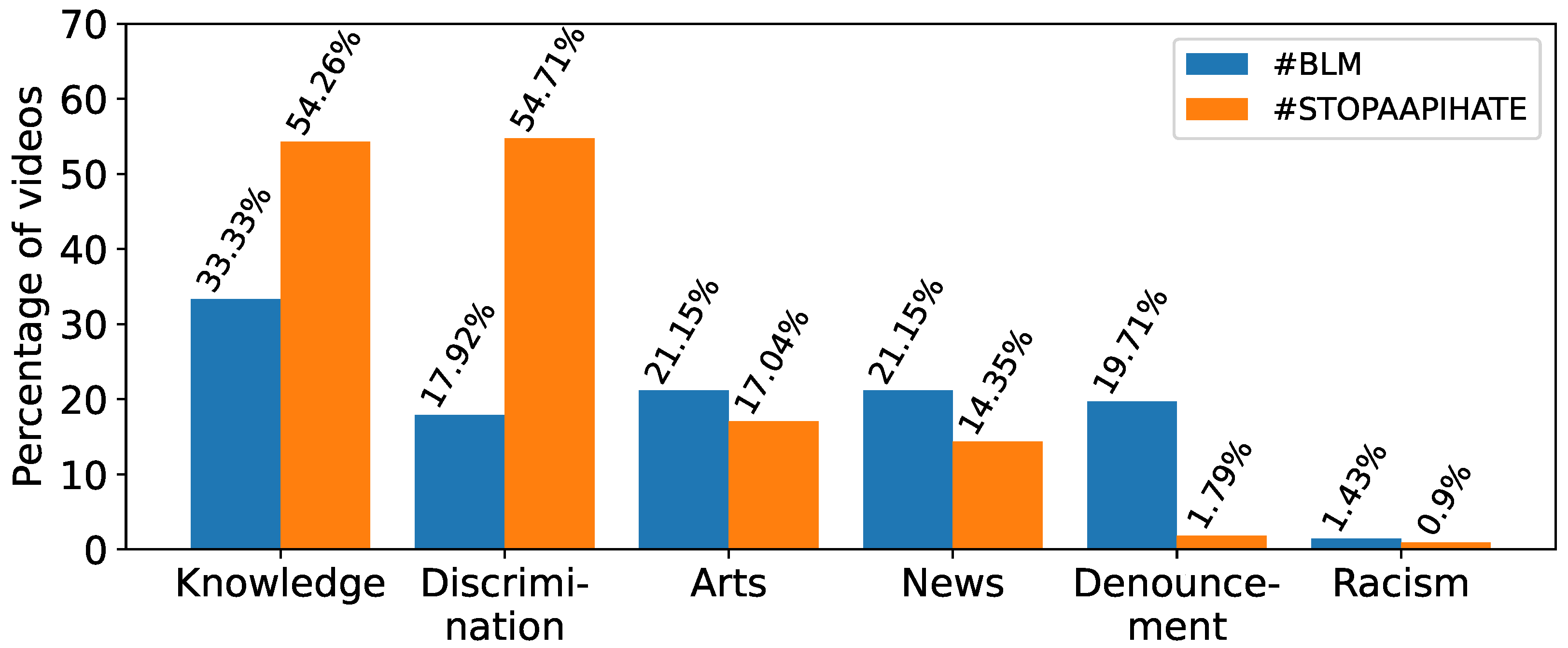

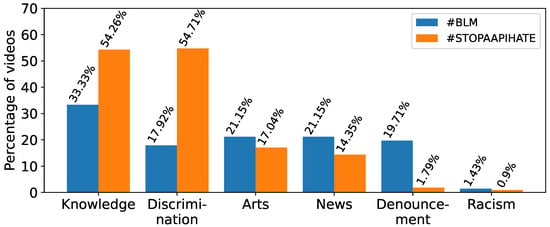

The information subthemes that arose through the thematic analysis were movement education and knowledge, discrimination and racism faced by the minority group, videos showcasing art, news, and recordings of protests/rallies, denouncing and criticizing the movement, and discriminating against a minority group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Information subtheme distribution, ordered by descending percentage of videos.

In our data, the predominant subtheme was knowledge and information about the movements, which was discussed in 42.74% () of all videos. Specifically, 54.26% of the videos related to #StopAAPIHate and 33.33% of those related to #BLM addressed this subtheme. Videos in this category notably provided knowledge and information on a variety of topics, including background, facts, motivations, and other relevant content associated with both movements. For example, “Pseudo-Religion or Social Poetry: Black Lives Matter and the Catholic Church” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bBWdqCHzyXg (accessed on 31 December 2024)) illustrates a Zoom presentation delving into the history of the Black Lives Matter movement and its connection to the Catholic Church. Similarly, “Stop the Hate-Episode 1” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlF552GNKAI&t=2s (accessed on 31 December 2024)) features a sociologist discussing the factors contributing to the rise in anti-Asian sentiment during the pandemic.

Discussing discrimination emerged as the second most prevalent subtheme, representing 33.95% () of the sample. These videos highlighted stories and personal experiences of racial issues—including oppression, discrimination, unfairness, police brutality, and hate crimes—faced by Black and Asian individuals. For example, the video entitled “The state of racial equality following Black Lives Matter protests” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7goLaudnTs8 (accessed on 31 December 2024)) features an activist discussing racial equality and the unfair treatment of Black people in America. Similarly, the video titled “Stop AAPI Hate” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BT-Ftz7UVm0&t=1s (accessed on 31 December 2024)) includes clips of Asian Americans reading a letter about the surge in hate crimes against Asians.

Videos featuring art as an informational subtheme constituted 19.22% () of the sample. These videos displayed various artistic expressions connected to either movement, including paintings, graffiti, music, films, and skits. For example, “Photo Essay: Miami Art Exhibition Inspired By Black Lives Matter Movement” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yL_NfCknqSs (accessed on 31 December 2024)) highlights an artist explaining how his exhibit draws inspiration from the #BLM movement. Similarly, “The Dividing Line || Spoken Word || Stop Asian Hate” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GT-FsUaNpqk (accessed on 31 December 2024)) showcases a creator performing a poetry piece addressing the surge in anti-Asian sentiment.

Following art, the most prevalent subtheme was news and protest footage, accounting for 18.20% () of the videos analyzed. This category encompassed content from reputable news outlets as well as unofficial or informal recordings of protests and rallies tied to the movements. For example, the video “How Would Police Respond If Black Lives Matter Stormed The Capitol? | The 11th Hour | MSNBC” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=urZb52tn0jo(accessed on 31 December 2024)) features a news interview discussing the disparities in police reactions to the Black Lives Matter protests compared to the Capitol storming. “US hate crimes: ‘Asian women are not weak, timid or quiet’-BBC News” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NTTbo1OdTcY (accessed on 31 December 2024)) presents a BBC segment on Asian women sharing their experiences.

Videos denouncing either movement had a lower frequency in the sample, with only 11.66% () of the videos categorized under this subtheme. Denouncing the movement was specifically defined as videos that criticized the organizers or organizations associated with the movements. These videos could criticize riots related to the movements, as well as alleged bribes or scandals involving movement leaders. For example, “Black Lives Matter in a Nutshell” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w8xuoiBJPKU (accessed on 31 December 2024)) features a creator criticizing the riots and use of violence in #BLM protests through a parody. “Dr. Eugene Gu’s Tweet About Black On Asian Issues Is Ignorant” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nm1oChdJeG8 (accessed on 31 December 2024)) shows a creator justifying anti-Asian comedy.

Thus, most videos about #BLM and #StopAAPIHate raised awareness about experiences of discrimination and educated their viewers. In addition to sharing knowledge, #BLM videos also spread movement information through art and news. One could hypothesize that, as a relatively nascent movement, #StopAAPIHate is still working to mobilize resources by raising awareness and providing education. On the other hand, #BLM, as a more established movement, has a foundation of resources and focuses on more tangible actions such as protests, news appearances, and creating art pieces. Another interesting finding is that, specifically regarding #BLM, videos criticizing the Black Lives Matter organization are prevalent. These videos often support the ideology or principles behind the movement but not the actual organization.

4.2.2. Storytelling

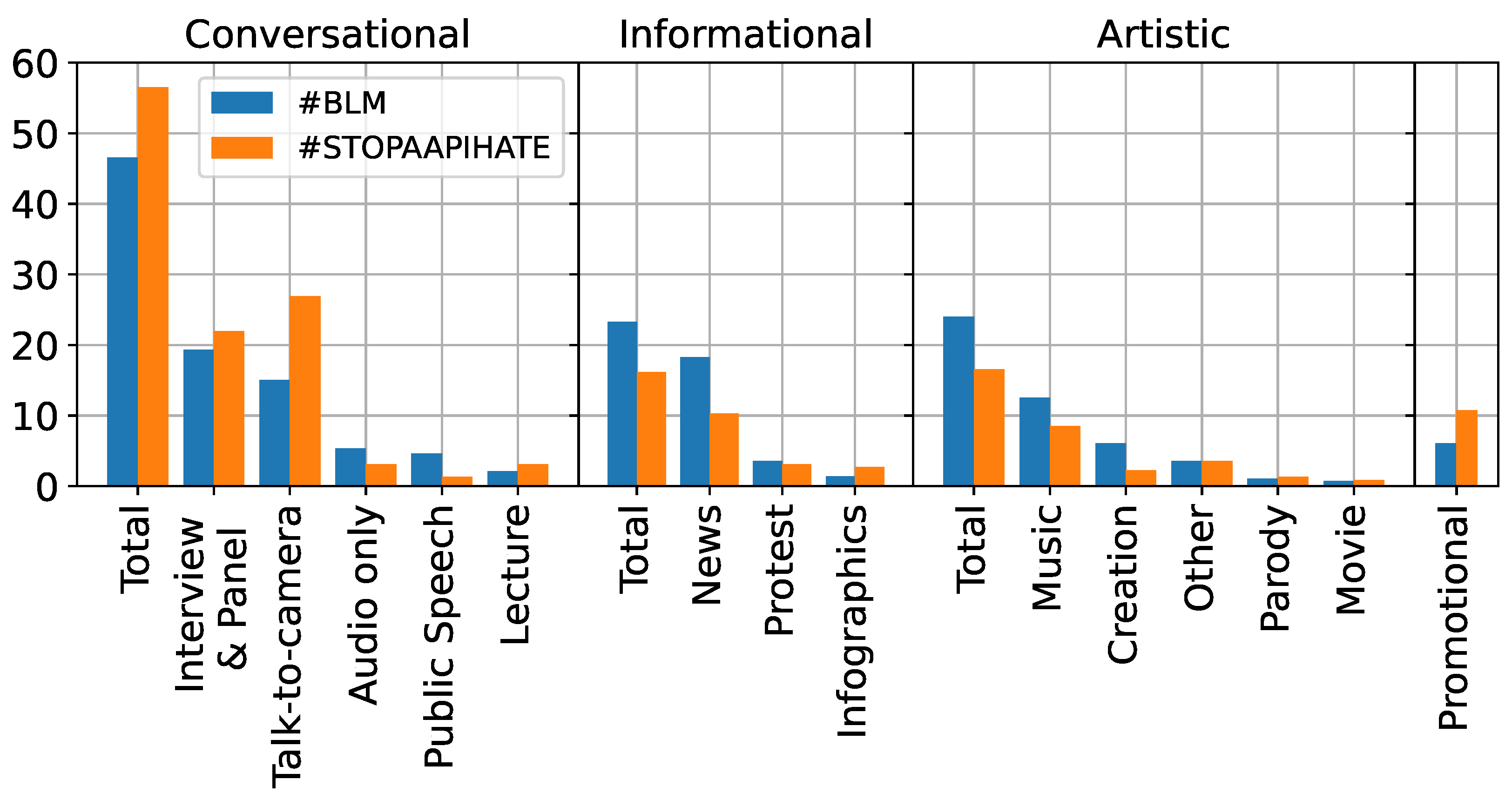

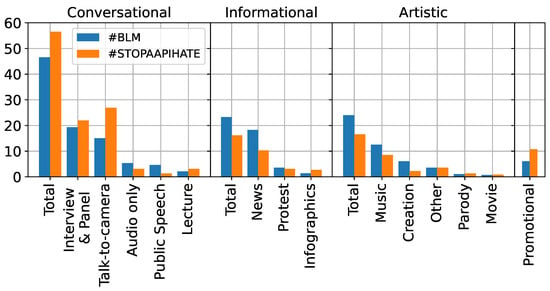

Conversational videos comprised a substantial portion of the sample, with 50.72% () of videos representing this category (Figure 3). The most common subthemes were talk-to-camera and interviews/panels, each making up 20.04% () of the total sample. “Asian books to fight racism (book recommendations)” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZXVMGmsBbGI (accessed on 31 December 2024)) shows an example of a talk-to-camera video where the creator talks to the camera and suggests Asian books to combat racism. “Black Lives Matter says Twerk on Washington for MLK day” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TfWkshrzL4 (accessed on 31 December 2024)) showcases a video with the interviews and panels subtheme, where five people discuss and criticize the Black Lives Matter organization.

Figure 3.

Storytelling subtheme distribution, ordered by descending percentage of videos.

Audio-only/voiceover videos were the next most common subtheme within the conversational subtheme, comprising 4.50% () of the sample. These videos are audio/voiceovers of the speaker. For example, “the problem with Black Lives Matter” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cv9ANuTgiXE (accessed on 31 December 2024)) is a voiceover video showing moving pictures while discussing problems with the Black Lives Matter movement.

The subtheme of public speeches and sermons made up 3.27% () of the entire sample. This included videos of public speeches to a live audience, as well as religious sermons. For example, in “The Hypocrisy Of Black Lives Matter #ISUPK #SOUTHCAROLINA” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lu07B-vY7rU (accessed on 31 December 2024)), several people make a public speech commenting on the hypocrisy of Black Lives Matter. In “Moving Mountains: #StopAsianHate | A Vigil Honoring Victims of Anti-Asian Violence” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fso-_EvWowA (accessed on 31 December 2024)), a person delivers a public speech at a vigil for victims of anti-Asian violence.

The least frequent conversational subtheme was lectures and presentations, accounting for only 2.66% () of the sample. These videos were either live or Zoom recordings of presentations, lectures, and slide shows. “Black Lives Matter Pt 1” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a8FfFTOu9_8 (accessed on 31 December 2024)) illustrates this subtheme with a Zoom recording of a presentation about the importance of BLM.

Videos involving informational presentations were the next most common main storytelling subtheme, accounting for 21.06% () of the sample. These videos focused on conveying information and facts and included the following subthemes: protest videos, news, and infographics. The most common subtheme within informational storytelling was news, with 15.13% () of the total video sample classified under this subtheme. These videos featured news reports from established organizations, as seen in “New book on talking to kids about Black Lives Matter” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M3-PL3nQwz4 (accessed on 31 December 2024)), where reporters interview the author of a children’s book about the BLM movement.

The second most common subtheme was protest videos, comprising 3.50% () of the sample. These included recordings of protests or rallies related to either movement, as shown in the video “Activist gets arrested after a Black Lives Matter-crowd forced their way into the Iowa State Capitol” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQAu7zc0hSU (accessed on 31 December 2024)), which depicts a protester being arrested at a Black Lives Matter protest. Similarly, “(OFFICIAL AFTERMOVIE) #StopAsianHate Community Rally-San Jose, CA, USA-21 March 2021” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxVnYCTLSBY (accessed on 31 December 2024)) shows several people speaking at a #StopAAPIHate rally.

The least common subtheme was infographics, representing only 2.05% () of the sample. These videos featured infographics or other static elements or images used to present facts about either movement. “Stop AAPI Hate | Lifetime” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMRGXppznXI (accessed on 31 December 2024)) shows a video with infographics about the rise in anti-Asian hate incidents following the pandemic.

Artistic videos made up 18.61% () of the sample and included videos where storytelling occurred through the depiction of movement-related art creation. These videos comprised the following subthemes: music, paintings/other creations, parodies/skits, and movies. The most common subtheme within artistic videos was music, constituting 10.63% () of the sample. This category included music or lyric videos, often featuring original music created in reference to either movement.

Videos featuring paintings or other creations (such as graffiti or t-shirts) related to either movement accounted for 4.29% () of the sample. For example, “Black Lives Matter Quilt for the Clothesline” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lvRFCIv3-3Y (accessed on 31 December 2024)) shows a creator making a quilt with the words “Black Lives Matter”, while “PLAN WITH ME March 2021 Bullet Journal Setup Juice Box Theme!” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-tOT6QgircU (accessed on 31 December 2024)) depicts a creator making art to raise funds for #StopAAPIHate charities.

Videos that included parodies or skits about either movement made up 1.23% () of the sample. For instance, “Do you say Black Lives Matter? TikTok” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WuFm6RhJ0QQ (accessed on 31 December 2024)) shows a creator lip-syncing “Do you say Black Lives Matter?” while the on-screen text reads, “Me to my white teachers that give me Fs”. Finally, movies were the least common subtheme, comprising only 0.61% () of the sample. These films were inspired by issues related to both movements. “Otherness - A Film By Chris Bergt” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1yfZ7AIwUYA (accessed on 31 December 2024)) depicts a movie about a person facing anti-Asian racism and his response to it.

Lastly, promotional videos were the least common, comprising only 8.38% () of the sample. These videos featured short promotions of the movement, such as holding up signs or slogans in support of the movement, as shown in “Black Lives Matter Flag Raising” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y0Lk6IkPtHs (accessed on 31 December 2024)), or promoting a Facebook group, like in “Empowered Asians-FB Group-Safe space to share ideas and take action to #StopAsianHate” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xGLhZO-Kpw8 (accessed on 31 December 2024)).

Within the subtheme of storytelling techniques, conversational-style videos comprised half of the sample. This is notable, as it demonstrates a more personable form of storytelling, likely to build connections with the audience. This is further supported by the fact that the most common storytelling subthemes were talk-to-camera videos and interviews/panels. Thus, videos that engage viewers in conversation or showcase speakers interacting in dialogue, likely making the viewers feel indirectly involved, are strategies used by video creators to engage their audience in conversations about racism.

4.3. RQ3: Audience Interaction

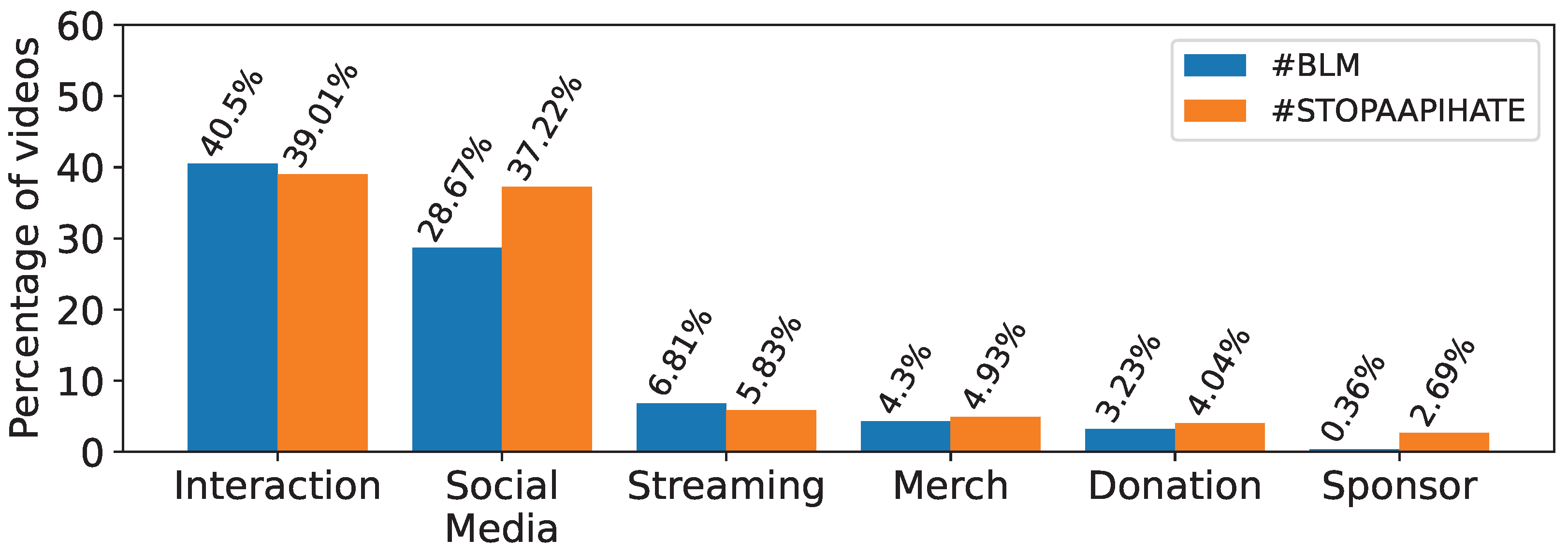

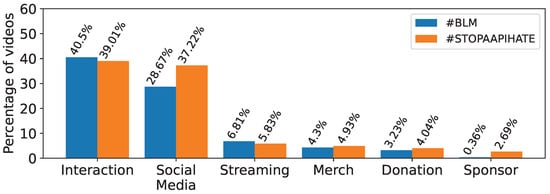

The majority of videos did not feature any explicit form of audience interaction, categorized as “none”, representing 44.58% () of the sample (Figure 4). In these videos, creators did not engage with viewers using any of the available interaction tools. Among videos that did encourage interaction, techniques included using platform interaction features, promoting social media accounts, live streaming, merchandise promotion, requesting donations, and showcasing sponsorships.

Figure 4.

Interaction subtheme distribution, ordered by descending percentage of videos.

The most popular approach was through the use of platform interaction features, with videos in this category making up 39.67% () of the sample. This category included videos that utilized YouTube’s platform features and encouraged viewers to like, comment, subscribe, and/or share the video. For instance, in the video “What is social etiquette? | Comedy and Asian bias” (https://www.youtube.com/embed/IkwgO8g_uWU (accessed on 31 December 2024)), the creator concludes by instructing viewers to “1 Like, 2 Share, 3 Subscribe”.

Another popular way of engaging was through advertising different social media platforms, such as Instagram or Twitter, and encouraging viewers to follow the creator on these platforms. These videos made up 32.11% () of the sample. In the video “Black Lives Matter, 2020 Elections, Covid19-EPISTEMOLOGY” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q1PYdX_sGws (accessed on 31 December 2024)), the YouTuber lists Twitter and YouTube handles in the video description.

Live streams (), donations (), merchandise (), and sponsors () were used only infrequently in videos as forms of audience interaction. Videos that were streamed live allowed viewers to chat simultaneously and donate to the creator. For example, the video “Black Lives Matter says Twerk on Washington for MLK day” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TfWkshrzL4 (accessed on 31 December 2024)) is a recording of a live conversation about #BLM. Videos that either featured the creator asking viewers to donate or included links for donation were classified under the donation category. For instance, “NFL brings back BLACK LIVES MATTER helmet decals and more WOKENESS just in time for the NFL Season!” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eeBHFi6G9js (accessed on 31 December 2024)) shows the creator listing their Patreon, a website where viewers can pay to support the creator and gain access to exclusive content. Some videos also featured merchandise sold by the video creator, such as in “Digital Art with Houdini-#STOPASIANHATE” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8CKqNZgvzU (accessed on 31 December 2024)), where the creator lists their merchandise website in the video description. Finally, some videos included an ad from a sponsor, as seen in “Misogyny Against Asian Women-The TryPod Ep. 102” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VMd3S3BOarU (accessed on 31 December 2024)), where the video displays a sponsor’s logo while the creator provides a voiceover describing the sponsor.

The prevalence of no interaction as the most common form suggests that video creators are not fully utilizing the tools available to them. The most commonly used approach to connect with the audience is calling for subscriptions and comments and promoting social media accounts. However, YouTubers do not actively use live streaming, merchandise, donation links, or sponsorship to support the movement.

5. Discussion

5.1. Public Figures and Vloggers in YouTube Movement Participation

RQ1 explored identifying key creators in social movements on YouTube. Our findings suggest that a significant portion of these videos feature public figures, accounting for approximately 35% in both the #BLM and #StopAAPIHate movements on YouTube. Additionally, vloggers make up a notable segment of the creators, comprising 26.88% for #BLM and 42.6% for #StopAAPIHate. The content spectrum also includes news reporters, artists, the general public, and religious figures sharing their perspectives on YouTube. Thus, unlike on Twitter and Facebook, where the identity of posters is not significant and rarely shared [12], various identities of creators are shared on YouTube, playing an important role in shaping the content of the videos.

Notably, vloggers are key contributors to the relatively new movement StopAAPIHate. They distinguish themselves from text-centric influencers by fostering a strong sense of community and solidarity for racial minorities through video content [6]. Vloggers mobilize resources through techniques like sharing personal stories and speaking “face-to-face” via talk-to-camera videos, creating a stronger connection and shared identity with their audience. This solidarity is crucial for creating a “cyberplace” of shared identities, thereby mobilizing resources and inspiring action in social movements [2,19]. Public figures also made up a sizable percentage of the videos discussing these social movements. This group included activists and celebrities, as well as individuals in more professional public roles, such as professors and politicians. Two unique identities that emerge on YouTube are those of artists and religious figures. While these identities did not constitute a significant portion compared to public figures and vloggers, they are notable because there are no comparable studies on other platforms where users showcase their artistry or religiosity for social movements. Finally, the representation of ordinary people is a small category, contrasting with other social media platforms where ordinary people are the primary source of voices. YouTube features ordinary individuals, who are not associated with a specific occupation or identity, expressing their opinions. Despite this small representation of ordinary people, the majority of the content pertaining to #BLM and #StopAAPIHate was created by vloggers, which highlights YouTube’s unique contribution to activist content. Furthermore, it opens up potential for mobilization given that many vloggers are micro-celebrities who often have a fanbase and large following [23,24].

Our analysis suggests several key directions to support social movements and communities on video-sharing platforms. First, given that public figures and vloggers create the majority of videos related to #BLM and #StopAAPIHate, researchers should investigate the impact of these videos on viewers, specifically exploring whether audiences perceive them positively or negatively. This insight is particularly valuable since many creators have large followings, potentially enabling their videos to significantly mobilize support for social justice movements. Such research would equip YouTube creators with essential feedback to refine their content and enhance their contributions to movement propagation. Second, artists who creatively support social movements through diverse forms of artistic expression and cultural crafts should receive greater development opportunities. YouTube, as a video platform, is particularly suited to showcasing various art forms, from paintings and crafts to skits and short films [44]. Sharing artistic content plays a critical role in fostering a sense of community and unity, both essential for the growth and momentum of social movements. Given the significant presence of artists within social movements on YouTube, it is crucial for the platform to acknowledge and support their needs for increased visibility and engagement. Additionally, understanding how public exposure through social media activism affects creators’ everyday lives—particularly those whose online identities are not typically associated with activism, such as religious figures or artists—is essential for managing potential consequences and ensuring positive impacts on their personal and professional experiences. Lastly, the limited involvement of ordinary individuals in video creation suggests that many people may lack the knowledge or resources needed to use videos effectively in support of social movements. Future research should examine the underlying factors that limit public participation and propose actionable strategies to encourage broader involvement from general audiences on video-sharing platforms.

5.2. Informal Information and Conversation About Racial Movements

The most common types of information shared in #BLM and #StopAAPIHate videos revolve around movement knowledge and personal stories of discrimination. This finding suggests that YouTube primarily facilitates the dissemination of educational content and firsthand experiences related to racial discrimination, rather than misinformation or racist rhetoric. This information-sharing pattern is consistent with posts observed on text-based platforms like Twitter [14,16,17]. However, our analysis also reveals that #StopAAPIHate videos are more likely to feature personal stories of discrimination compared to #BLM videos. This difference may be attributed to the relatively recent emergence of the #StopAAPIHate movement, where creators are actively raising awareness through personal storytelling. In contrast, the more established BLM movement frequently emphasizes educational content and actionable steps for social change—for example, by sharing seminars that explore the history, objectives, and criticisms of Black Lives Matter.

Another interesting discrepancy between the two movements is that the number of videos denouncing the Black Lives Matter organization is greater than that of videos denouncing the StopAAPIHate. One explanation for this difference could be that since BLM is an older movement than StopAAPIHate, it has likely gained more prominence, thus leading to more opportunities for pushback [45]. Past studies on Twitter and Facebook have explored the rise of BLM countermovement groups [12,15,46], suggesting that this denouncement is not unique to YouTube. This difference in criticism and denouncement between the two movements could be an avenue for future studies to investigate.

Within the subtheme of storytelling techniques, conversational-style videos comprised half of the sample. A significant portion of the videos were created by vloggers, demonstrating the popularity of a more personable storytelling approach when delivering information about social movements like #BLM and #StopAAPIHate. This trend is further supported by the prevalence of talk-to-camera videos, interviews, and panel discussions as the most common subthemes. These storytelling techniques combine information and identity approaches by disseminating content while also fostering a sense of community among viewers. By engaging them in conversation or showcasing discussions, YouTube creators help viewers feel directly or indirectly like part of the movement, cultivating a sense of solidarity [2]. This stands in stark contrast to Twitter and Facebook, where information is mostly conveyed through text posts, making it challenging to establish a more personable storytelling format.

Our analysis and findings on the information and storytelling subthemes have several implications. First, YouTube is actively utilized by creators to share stories of discrimination, frequently involving personal experiences. As these video creators publicly disclose personal information, concerns may arise regarding their safety and privacy. Therefore, YouTube should implement mechanisms to manage video searchability, restrict the exposure of sensitive personal information, and offer identity-concealment features. These measures would enable users to safely share personal narratives about racial discrimination while minimizing risks of online harassment. Second, video creators are adopting conversational styles to communicate with viewers. This underscores the value of informal approaches over more formal, traditional ones on YouTube. Considering that a majority of the videos were made by vloggers, such an informal conversational style might foster PSIs among viewers. This has important implications for viewers’ engagement with the movement, especially given that PSIs have been associated with increased persuasion [31,32]. Thus, it is crucial that future research better understand PSIs via YouTube videos and explore their impact on viewers’ decisions to participate in a social movement.

5.3. Lack of Use of Video-Sharing Platform Features

Our analysis indicates that the most common methods employed by #BLM and #StopAAPIHate creators involve encouraging viewers to interact directly with videos or sharing their social media handles. Previous research emphasizes the importance of utilizing interaction tools to maintain an active online presence, thus enhancing reach and mobilization [1]. Additionally, prior studies suggest that viewers who primarily seek information on YouTube are more inclined to use interactive features like likes, dislikes, or comments [47]. However, our findings reveal that most video creators do not fully leverage unique platform features such as live streaming, merchandise sales, donation links, and sponsorships. One possible explanation is the availability of alternative platforms better suited for these specific features. For example, Twitch, a platform dedicated to live streaming, hosts significantly more live stream channels than YouTube [48]. These observations suggest that YouTube should enhance these interaction tools to better align with features offered by competing social media platforms or to increase their accessibility and appeal to creators [31,32]. Although other forms of engagement—such as donations, live streaming, and merchandise—were less common, they represent growing opportunities for user interaction on YouTube.

It is important to acknowledge that the findings may be influenced by the data collection methods used in this study. For example, not all live streams are archived and uploaded as videos after broadcast, meaning that additional relevant content may exist but was not captured in our dataset. Future research should further investigate these forms of interaction to assess their effectiveness in promoting social movements and mobilizing resources. For example, it would be valuable to explore how different movement strategies and the use of platform features influence public response and fundraising efforts—either positively or negatively—on video platforms, given that resource mobilization has long been a core aspect of social movements [33].

6. Conclusions

By analyzing a dataset of 489 videos, we identified various themes related to the identities of video creators, the information presented, storytelling techniques, and audience interaction. This study highlights YouTube’s distinctive role in supporting social justice movement videos for #BLM and #StopAAPIHate. Our results reveal a broad spectrum of creators, including vloggers, artists, public figures, and ordinary individuals, with public figures and vloggers representing the largest groups. Videos primarily focused on discrimination, movement education, and protest coverage, with conversational storytelling styles being used most frequently.

The findings suggested that the most common kinds of #BLM and #StopAAPIHate videos were highly personable, with most videos from this sample arising from vloggers, featuring stories and experiences of racism, and being delivered in a conversational style. Such personable videos could suggest PSIs between viewers and the creator, which would make these videos effective in mobilizing support for social movements, considering the evidence for the persuasive nature of PSIs [31,32]. Thus, vloggers can create a sense of community and mobilize this community towards helping social movements, thereby creating a “cyberplace” with a common shared goal [2]. Consequently, YouTube offers a unique niche for content creators to unite their audiences in support of social movements, often through “talk-to-camera” interaction.

Although our results confirm YouTube’s potential as a critical platform for social change, it also exposes gaps between this potential and the current level of engagement. For instance, YouTube’s video platform allows for showcasing arts in different media; however, this is not reflected in the number of videos created by artists. Hence, YouTube must better address the needs of this distinctive community and support them in improving video engagement. Furthermore, a significant proportion of creators do not fully utilize interactive features like live streaming, donations, and merchandise sales, which could enhance their impact and strengthen movement participation. YouTube should support video creators in their efforts to utilize these features meaningfully and make them more accessible.

This study also provides direction for future research on YouTube and social movements. With the majority of the video sample being created by vloggers, it is critical to investigate whether such research has a positive impact in terms of actual audience participation and mobilization. Additionally, future studies should also explore which kinds of identities, video content, and storytelling techniques are the most effective at mobilizing support for social movements. Such research would be key in supporting YouTube content creators with activism content, and enable them to effectively drive audience engagement. Therefore, by offering an intricate typology of social movements on YouTube, this research lays the groundwork for future exploration into improving engagement mechanisms and leveraging YouTube’s unique affordances to foster more effective communication and support for social justice initiatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and S.N.; methodology, A.B. and S.N.; validation, A.B. and S.N.; formal analysis, A.B. and S.N.; investigation, A.B. and S.N.; resources, S.N.; data curation, A.B. and S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, S.N.; visualization, S.N.; supervision, S.N.; project administration, S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BLM | Black Lives Matter |

| AAPIs | Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders |

References

- Mundt, M.; Ross, K.; Burnett, C.M. Scaling Social Movements Through Social Media: The Case of Black Lives Matter. Soc. Media Soc. 2018, 4, 2056305118807911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, D. YouTube and Social Movements: A Phenomenological Analysis of Participation, Events and Cyberplace. Antipode 2012, 44, 1429–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, D.; Kim, G. YouTube, Critical Pedagogy, and Media Activism. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 2010, 32, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poell, T.; van Dijck, J. Social media and new protest movements. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media; Burgess, J., Marwick, A., Poell, T., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2018; pp. 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askanius, T.; Uldam, J. Online social media for radical politics: Climate change activism on YouTube. Int. J. Electron. Gov. 2011, 4, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.J.; Sherrell, D.L. Source effects in communication and persuasion research: A meta-analysis of effect size. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1993, 21, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.; Niebuhr, O.; Zellers, M. A Preliminary Study of Charismatic Speech on YouTube: Correlating Prosodic Variation with Counts of Subscribers, Views and Likes. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2019, Graz, Austria, 15–19 September 2019; pp. 1761–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S.; Craig, D. Being ‘really real’ on YouTube: Authenticity, community and brand culture in social media entertainment. Media Int. Aust. 2017, 164, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitts, J. Mobilizing in black boxes: Social networks and participation in social movement organizations. Mobilization Int. Q. 2000, 5, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorson, K.; Driscoll, K.; Ekdale, B.; Edgerly, S.; Thompson, L.G.; Schrock, A.; Swartz, L.; Vraga, E.K.; Wells, C. Youtube, twitter and the occupy movement. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2013, 16, 421–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, D.; McIntosh, K. Social media and social movements. Sociol. Compass 2016, 10, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L.G.; Arif, A.; Nied, A.C.; Spiro, E.S.; Starbird, K. Drawing the Lines of Contention: Networked Frame Contests Within #BlackLivesMatter Discourse. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2017, 1, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Jang, A. Questing for Justice on Twitter: Topic Modeling of #StopAsianHate Discourses in the Wake of Atlanta Shooting. Crime Delinq. 2023, 69, 2874–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Lee, C.; Sun, W.; De Gagne, J.C. The #StopAsianHate Movement on Twitter: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lee, A. Black Lives Matter and Its Counter-Movements on Facebook (December 7, 2021). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3980259 (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Tong, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Bei, R.; Zhang, L. What are People Talking about in #BackLivesMatter and #StopAsianHate? Exploring and Categorizing Twitter Topics Emerged in Online Social Movements through the Latent Dirichlet Allocation Model. In Proceedings of the 2022 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, AIES ’22, New York, NY, USA, 19–21 May 2021; pp. 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, S. From #BlackLivesMatter to #StopAsianHate: Examining Network Agenda-Setting Effects of Hashtag Activism on Twitter. Soc. Media Soc. 2022, 8, 20563051221146182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, D.S. “When you Search a #Hashtag, it Feels Like You’re Searching for Death”: Black Twitter and Communication About Police Brutality Within the Black Community. Soc. Media Soc. 2023, 9, 20563051231179705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Santero, N.K.; Kaneshiro, B.; Lee, J.H. Armed in ARMY: A Case Study of How BTS Fans Successfully Collaborated to #MatchAMillion for Black Lives Matter. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Syste, CHI ’21, New York, NY, USA, 8–13 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.R. The impact of social media on social movements: The new opportunity and mobilizing structure. J. Political Sci. Res. 2014, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Arthurs, J.; Drakopoulou, S.; Gandini, A. Researching YouTube. Convergence 2018, 24, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Mai, C.; McKim, K.G.; McCrickard, D.S. #TeamTrees: Investigating How YouTubers Participate in a Social Media Campaign. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 5, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, S.; Ang, L.; Welling, R. Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebr. Stud. 2017, 8, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R. “This Is What the News Won’t Show You”: YouTube Creators and the Reactionary Politics of Micro-celebrity. Telev. New Media 2019, 21, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knupfer, H.; Neureiter, A.; Matthes, J. From social media diet to public riot? Engagement with ‘greenfluencers’ and young social media users’ environmental activism. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Golan, G.J. Social Media Activism in Response to the Influence of Political Parody Videos on YouTube. Commun. Res. 2011, 38, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofia Triliva, C.V.; Dafermos, M. YouTube, young people, and the socioeconomic crises in Greece. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibble, J.L.; Hartmann, T.; Rosaen, S.F. Parasocial Interaction and Parasocial Relationship: Conceptual Clarification and a Critical Assessment of Measures. Hum. Commun. Res. 2016, 42, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, D.C. Parasocial Interaction: A Review of the Literature and a Model for Future Research. Media Psychol. 2002, 4, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer-Gusé, E. Toward a Theory of Entertainment Persuasion: Explaining the Persuasive Effects of Entertainment-Education Messages. Commun. Theory 2008, 18, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.C.; Wu, L.W.; Chang, Y.Y.C.; Hong, R.H. Influencers on Social Media as References: Understanding the Importance of Parasocial Relationships. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukachinsky, R.; Walter, N.; Saucier, C.J. Antecedents and Effects of Parasocial Relationships: A Meta-Analysis. J. Commun. 2020, 70, 868–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.C. Resource mobilization theory and the study of social movements. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1983, 9, 527–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltantawy, N.; Wiest, J.B. The Arab spring| Social media in the Egyptian revolution: Reconsidering resource mobilization theory. Int. J. Commun. 2011, 5, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Gray-Hawkins, M. Collective movements, digital activism, and protest events: The effectiveness of social media concerning the organization of large-scale political participation. Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 2018, 10, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kavada, A. Engagement, bonding, and identity across multiple platforms: Avaaz on Facebook, YouTube, and MySpace. MedieKultur J. Media Commun. Res. 2012, 28, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattenhofer, M.; Wattenhofer, R.; Zhu, Z. The YouTube social network. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Dublin, Ireland, 4–7 June 2012; Volume 6, pp. 354–361. [Google Scholar]

- Sumiala, J.M.; Tikka, M. Broadcast Yourself—Global News! A Netnography of the “Flotilla” News on YouTube*. Commun. Cult. Crit. 2013, 6, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vraga, E.K.; Bode, L.; Wells, C.; Driscoll, K.; Thorson, K. The Rules of Engagement: Comparing Two Social Protest Movements on YouTube. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 17, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, N.S.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Park, H.W. Identifying the Impacts of Social Movement Mobilization on YouTube: Social Network Analysis. Information 2025, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, M.G.; Thomas, R.J. ‘This is citizen journalism at its finest’: YouTube and the public sphere in the Oscar Grant shooting incident. New Media Soc. 2010, 12, 1280–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.N. Race, Media, and the Crisis of Civil Society: From Watts to Rodney King; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Ip, B.; Lin, L. A Survey of Current YouTube Video Characteristics. IEEE Multimed. 2015, 22, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebron, C.J. The Making of Black Lives Matter: A Brief History of an Idea; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.L.; Kaye, L.K. Using Twitter Data to Explore Public Discourse to Antiracism Movements. Technol. Mind Behav. 2022, 3, 1–20. Available online: https://tmb.apaopen.org/pub/6nbhufpr (accessed on 31 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.L. Social media engagement: What motivates user participation and consumption on YouTube? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, K.; Simon, G. YouTube live and Twitch: A tour of user-generated live streaming systems. In Proceedings of the 6th ACM Multimedia Systems Conference, MMSys ’15, New York, NY, USA, 18–20 March 2015; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).