Single-Cell Transcriptomics and Computational Frameworks for Target Discovery in Cancer

Abstract

1. Tumor Ecosystems and Therapeutic Opportunities Revealed by Single-Cell Transcriptomics

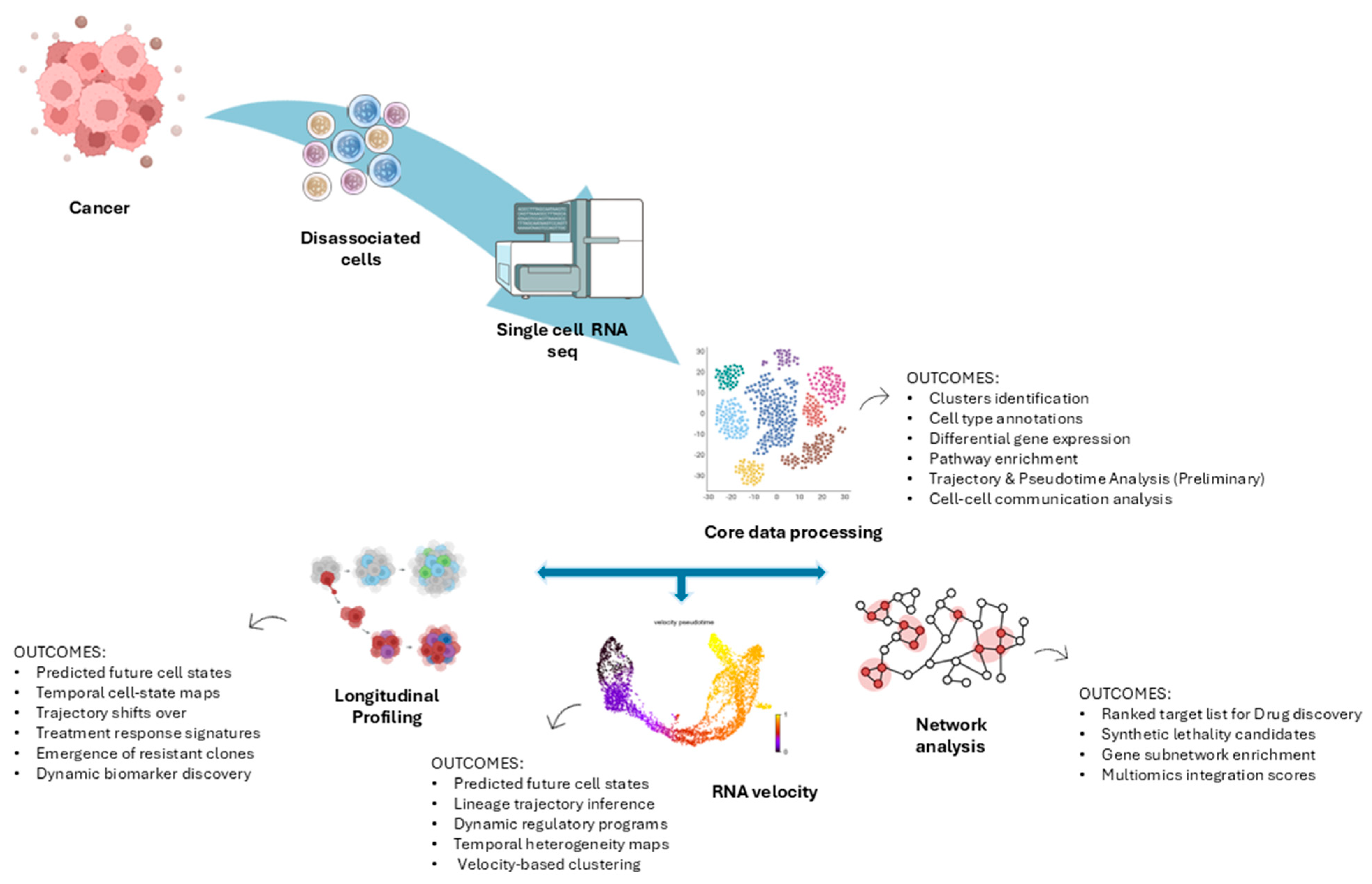

2. Computational Strategies for Target Discovery Using scRNA-Seq

2.1. Computational Frameworks for Target Discovery

2.2. Longitudinal Single-Cell Profiling in Cancer

2.3. RNA Velocity: Inferring Future Cell States

2.4. Network Diffusion for Druggable Target Discovery

3. Single-Cell Multi-Omics: Current Advances and Future Directions

3.1. Genome—Transcriptome Integration

3.2. Integrating Proteome-Transcriptome

3.3. Other Multi-Omics Integrations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TME | Tumor Micro Environment |

| scRNA-seq | Single-cell RNA sequencing |

| CNVs | Copy number Variations |

| PPI | Protein–Protein Interaction |

| AML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| NSCLC | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

References

- MacDonald, W.J.; Purcell, C.; Pinho-Schwermann, M.; Stubbs, N.M.; Srinivasan, P.R.; El-Deiry, W.S. Heterogeneity in Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, E.H.; Bahrami, A.R.; Matin, M.M. Cancer Cell Cycle Heterogeneity as a Critical Determinant of Therapeutic Resistance. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirosh, I.; Izar, B.; Prakadan, S.M.; Wadsworth, M.H., II; Treacy, D.; Trombetta, J.J.; Rotem, A.; Rodman, C.; Lian, C.; Murphy, G.; et al. Dissecting the Multicellular Ecosystem of Metastatic Melanoma by Single-Cell RNA-Seq. Science 2016, 352, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belote, R.L.; Le, D.; Maynard, A.; Lang, U.E.; Sinclair, A.; Lohman, B.K.; Planells-Palop, V.; Baskin, L.; Tward, A.D.; Darmanis, S.; et al. Human Melanocyte Development and Melanoma Dedifferentiation at Single-Cell Resolution. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 1035–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, P.P.; Pavet, V.; Marais, R. The Journey from Melanocytes to Melanoma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 23, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.F.; Simmons, J.L.; Boyle, G.M. Heterogeneity in Melanoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, A.; Yan, M.; Pang, B.; Pang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Ping, Y.; Hu, J. Dissecting Cellular States of Infiltrating Microenvironment Cells in Melanoma by Integrating Single-Cell and Bulk Transcriptome Analysis. BMC Immunol. 2023, 24, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Courtois, E.T.; Sengupta, D.; Tan, Y.; Chen, K.H.; Goh, J.J.L.; Kong, S.L.; Chua, C.; Hon, L.K.; Tan, W.S.; et al. Reference Component Analysis of Single-Cell Transcriptomes Elucidates Cellular Heterogeneity in Human Colorectal Tumors. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Guo, F.; Liu, Y. Spatial Transcriptomics and ScRNA-Seq: Decoding Tumor Complexity and Constructing Prognostic Models in Colorectal Cancer. Hum. Genom. 2025, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, J.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, M.; Chen, M.; Liu, C.; Ji, J.; Zhu, D. Single-Cell Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Tumor Immune Microenvironment Heterogenicity and Granulocytes Enrichment in Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases. Cancer Lett. 2020, 470, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdeolivas, A.; Amberg, B.; Giroud, N.; Richardson, M.; Gálvez, E.J.C.; Badillo, S.; Julien-Laferrière, A.; Túrós, D.; Voith von Voithenberg, L.; Wells, I.; et al. Profiling the Heterogeneity of Colorectal Cancer Consensus Molecular Subtypes Using Spatial Transcriptomics. npj Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, X.; Li, Q.; Qin, J.; Ye, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Wen, X.; Wang, Z.; He, W.; et al. Single-Cell and Spatial-Resolved Profiling Reveals Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Heterogeneity in Colorectal Cancer Metabolic Subtypes. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.P.; Tirosh, I.; Trombetta, J.J.; Shalek, A.K.; Gillespie, S.M.; Wakimoto, H.; Cahill, D.P.; Nahed, B.V.; Curry, W.T.; Martuza, R.L.; et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Highlights Intratumoral Heterogeneity in Primary Glioblastoma. Science 2014, 344, 1396–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbarth, D.; Wang, Y.A. Glioblastoma Heterogeneity at Single Cell Resolution. Oncogene 2023, 42, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez-Rubiano, E.G.; Rincón-Arias, N.; Shelton, W.J.; Salazar, A.F.; Sierra, M.A.; Bertani, R.; Gómez-Amarillo, D.F.; Hakim, F.; Baldoncini, M.; Payán-Gómez, C.; et al. Current Applications of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Glioblastoma: A Scoping Review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, J.; Sun, H.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, H.; Yu, C.; E, W.; Lai, S.; et al. A Single-Cell Survey of Cellular Hierarchy in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Dong, P.; Kong, J.; Sun, N.; Wang, F.; Sang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Guo, R.; et al. Targeted Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis Reveals Metabolic Reprogramming and the Ferroptosis-Resistant State in Hematologic Malignancies. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2023, 41, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Galen, P.; Hovestadt, V.; Wadsworth, M.H.; Hughes, T.K.; Griffin, G.K.; Battaglia, S.; Verga, J.A.; Stephansky, J.; Pastika, T.J.; Lombardi Story, J.; et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals AML Hierarchies Relevant to Disease Progression and Immunity. Cell 2019, 176, 1265–1281.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldini, M.M.; Casirati, G.; Barcella, M.; Rancoita, P.M.V.; Cosentino, A.; Caserta, C.; Pavesi, F.; Zonari, E.; Desantis, G.; Gilioli, D.; et al. Longitudinal Single-Cell Profiling of Chemotherapy Response in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satija, R.; Farrell, J.A.; Gennert, D.; Schier, A.F.; Regev, A. Spatial Reconstruction of Single-Cell Gene Expression Data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.A.; Angerer, P.; Theis, F.J. SCANPY: Large-Scale Single-Cell Gene Expression Data Analysis. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, D.; Wang, S.; Shan, Y.; Liu, C.; Gu, J. ScCancer: A Package for Automated Processing of Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data in Cancer. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, A.; Tripathi, P.; Dubey, N.; Aier, I.; Kumar Varadwaj, P. Navigating Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing: Protocols, Tools, Databases, and Applications. Genom. Inform. 2025, 23, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, F.R.; Heya, N.R.; Hafiz, M.S.; Jim, J.R.; Kabir, M.M.; Mridha, M.F. A Systematic Review of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Applications and Innovations. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2025, 115, 108362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berge, K.; Roux de Bézieux, H.; Street, K.; Saelens, W.; Cannoodt, R.; Saeys, Y.; Dudoit, S.; Clement, L. Trajectory-Based Differential Expression Analysis for Single-Cell Sequencing Data. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Street, K.; Risso, D.; Fletcher, R.B.; Das, D.; Ngai, J.; Yosef, N.; Purdom, E.; Dudoit, S. Slingshot: Cell Lineage and Pseudotime Inference for Single-Cell Transcriptomics. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efremova, M.; Vento-Tormo, M.; Teichmann, S.A.; Vento-Tormo, R. CellPhoneDB: Inferring Cell–Cell Communication from Combined Expression of Multi-Subunit Ligand–Receptor Complexes. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 1484–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browaeys, R.; Saelens, W.; Saeys, Y. NicheNet: Modeling Intercellular Communication by Linking Ligands to Target Genes. Nat. Methods 2019, 17, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, D. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for Studying Human Cancers. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 2023, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Liu, L. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Technologies and Computational Analysis Tools: Application in Cancer Research. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2413, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxer, E.; Feigin, N.; Tschernichovsky, R.; Darnell, N.G.; Greenwald, A.R.; Hoefflin, R.; Kovarsky, D.; Simkin, D.; Turgeman, S.; Zhang, L.; et al. Emerging Clinical Applications of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 22, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramazzotti, D.; Angaroni, F.; Maspero, D.; Ascolani, G.; Castiglioni, I.; Piazza, R.; Antoniotti, M.; Graudenzi, A. LACE: Inference of Cancer Evolution Models from Longitudinal Single-Cell Sequencing Data. J. Comput. Sci. 2022, 58, 101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Minn, A.J.; Zhang, N.R. Assessing Intratumor Heterogeneity and Tracking Longitudinal and Spatial Clonal Evolutionary History by Next-Generation Sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5528–E5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Saddawi-Konefka, R.; Clubb, L.M.; Tang, S.; Wu, D.; Mukherjee, S.; Sahni, S.; Dhruba, S.R.; Yang, X.; Patiyal, S.; et al. Longitudinal Liquid Biopsy Identifies an Early Predictive Biomarker of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Response in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.C.; Zada, M.; Wang, S.Y.; Bornstein, C.; David, E.; Moshe, A.; Li, B.; Shlomi-Loubaton, S.; Gatt, M.E.; Gur, C.; et al. Identification of Resistance Pathways and Therapeutic Targets in Relapsed Multiple Myeloma Patients through Single-Cell Sequencing. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Manno, G.; Soldatov, R.; Zeisel, A.; Braun, E.; Hochgerner, H.; Petukhov, V.; Lidschreiber, K.; Kastriti, M.E.; Lönnerberg, P.; Furlan, A.; et al. RNA Velocity of Single Cells. Nature 2018, 560, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zha, H.; Liu, S.; Huang, D.; Fu, L.; Liu, X. Paradigms, Innovations, and Biological Applications of RNA Velocity: A Comprehensive Review. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergen, V.; Soldatov, R.A.; Kharchenko, P.V.; Theis, F.J. RNA Velocity—Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2021, 17, 10282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergen, V.; Lange, M.; Peidli, S.; Wolf, F.A.; Theis, F.J. Generalizing RNA Velocity to Transient Cell States through Dynamical Modeling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbioni, E.; Bibbona, E.; Mastrantonio, G.; Sanguinetti, G. BayVel: A Bayesian Framework for RNA Velocity Estimation in Single-Cell Transcriptomics. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.03083. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Chen, X.; Pan, X.; Deng, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Liao, D.; Xu, J.; Chen, M.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptome Analyses Reveal Critical Roles of RNA Splicing during Leukemia Progression. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, L.; Xia, H.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, X.; Sun, F.; Sun, L.; Li, S.; Li, D.; Wang, J.; et al. Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling after Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Revealed by Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salcher, S.; Sturm, G.; Horvath, L.; Untergasser, G.; Kuempers, C.; Fotakis, G.; Panizzolo, E.; Martowicz, A.; Trebo, M.; Pall, G.; et al. High-Resolution Single-Cell Atlas Reveals Diversity and Plasticity of Tissue-Resident Neutrophils in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 1503–1520.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoidi, O.; Fotiadou, E.; Nikolaidis, N.; Pitas, I. Graph-Based Label Propagation in Digital Media: A Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2015, 47, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofree, M.; Shen, J.P.; Carter, H.; Gross, A.; Ideker, T. Network-Based Stratification of Tumor Mutations. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersanelli, M.; Mosca, E.; Remondini, D.; Castellani, G.; Milanesi, L. Network Diffusion-Based Analysis of High-Throughput Data for the Detection of Differentially Enriched Modules. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanunu, O.; Magger, O.; Ruppin, E.; Shlomi, T.; Sharan, R. Associating Genes and Protein Complexes with Disease via Network Propagation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010, 6, e1000641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herwig, R.; Hardt, C.; Lienhard, M.; Kamburov, A. Analyzing and Interpreting Genome Data at the Network Level with ConsensusPathDB. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1889–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttlin, E.L.; Bruckner, R.J.; Paulo, J.A.; Cannon, J.R.; Ting, L.; Baltier, K.; Colby, G.; Gebreab, F.; Gygi, M.P.; Parzen, H.; et al. Architecture of the Human Interactome Defines Protein Communities and Disease Networks. Nature 2017, 545, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luck, K.; Kim, D.K.; Lambourne, L.; Spirohn, K.; Begg, B.E.; Bian, W.; Brignall, R.; Cafarelli, T.; Campos-Laborie, F.J.; Charloteaux, B.; et al. A Reference Map of the Human Binary Protein Interactome. Nature 2020, 580, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Olio, D.; Magnani, F.; Casadei, F.; Matteuzzi, T.; Curti, N.; Merlotti, A.; Simonetti, G.; Della Porta, M.G.; Remondini, D.; Tarozzi, M.; et al. Emerging Signatures of Hematological Malignancies from Gene Expression and Transcription Factor-Gene Regulations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, G.; Armano, G.; Frasca, M.; Lin, J.; Mesiti, M.; Re, M. RANKS: A Flexible Tool for Node Label Ranking and Classification in Biological Networks. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2872–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picart-Armada, S.; Thompson, W.K.; Buil, A.; Perera-Lluna, A. DiffuStats: An R Package to Compute Diffusion-Based Scores on Biological Networks. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 533–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yin, Z.; Lu, L. ISLRWR: A Network Diffusion Algorithm for Drug–Target Interactions Prediction. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0302281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, K.S.; Jose, A.; Bani, M.; Vinod, P.K. Network Diffusion-Based Approach for Survival Prediction and Identification of Biomarkers Using Multi-Omics Data of Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2023, 298, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, H.; Gunasekharan, V.; Qing, T.; Seay, M.; Surovtseva, Y.; Negahban, S.; Szallasi, Z.; Pusztai, L.; Gerstein, M.B. Network Propagation-Based Prioritization of Long Tail Genes in 17 Cancer Types. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroni, M.; Chiappori, F.; Paolini, E.; Longo, M.; De Caro, E.; Mosca, E.; Chiodi, A.; Merelli, I.; Badiali, S.; Maggioni, M.; et al. A Novel Gene Signature to Diagnose MASLD in Metabolically Unhealthy Obese Individuals. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 218, 115925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangelinck, A.; Molitor, E.; Marchiq, I.; Alaoui, L.; Bouaziz, M.; Andrade-Pereira, R.; Darville, H.; Becht, E.; Lefebvre, C. The Combined Use of ScRNA-Seq and Network Propagation Highlights Key Features of Pan-Cancer Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baysoy, A.; Bai, Z.; Satija, R.; Fan, R. The Technological Landscape and Applications of Single-Cell Multi-Omics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yang, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, J.; Guo, H.; Yang, R. Single-Cell Sequencing to Multi-Omics: Technologies and Applications. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, L.; Russell, A.J.C.; Voet, T. Single-Cell (Multi)Omics Technologies. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2018, 19, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, I.C.; Haerty, W.; Kumar, P.; Li, Y.I.; Hu, T.X.; Teng, M.J.; Goolam, M.; Saurat, N.; Coupland, P.; Shirley, L.M.; et al. G&T-Seq: Parallel Sequencing of Single-Cell Genomes and Transcriptomes. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.S.; Kester, L.; Spanjaard, B.; Bienko, M.; Van Oudenaarden, A. Integrated Genome and Transcriptome Sequencing of the Same Cell. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Meira, A.; O’Sullivan, J.; Rahman, H.; Mead, A.J. TARGET-Seq: A Protocol for High-Sensitivity Single-Cell Mutational Analysis and Parallel RNA Sequencing. STAR Protoc. 2020, 1, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.Y.; Kim, K.T.; Joung, J.G.; Son, D.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Jo, A.; Jeon, H.J.; Moon, H.S.; Yoo, C.E.; Chung, W.; et al. SIDR: Simultaneous Isolation and Parallel Sequencing of Genomic DNA and Total RNA from Single Cells. Genome Res. 2018, 28, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otoničar, J.; Lazareva, O.; Mallm, J.P.; Simovic-Lorenz, M.; Philippos, G.; Sant, P.; Parekh, U.; Hammann, L.; Li, A.; Yildiz, U.; et al. HIPSD&R-Seq Enables Scalable Genomic Copy Number and Transcriptome Profiling. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, T.R.; Talla, P.; Sagatelian, R.K.; Furnari, J.; Bruce, J.N.; Canoll, P.; Zha, S.; Sims, P.A. Scalable Co-Sequencing of RNA and DNA from Individual Nuclei. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Batista, A.; Jaén-Alvarado, Y.; Moreno-Labrador, D.; Gómez, N.; García, G.; Guerrero, E.N. Single-Cell Sequencing: Genomic and Transcriptomic Approaches in Cancer Cell Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeckius, M.; Hafemeister, C.; Stephenson, W.; Houck-Loomis, B.; Chattopadhyay, P.K.; Swerdlow, H.; Satija, R.; Smibert, P. Simultaneous Epitope and Transcriptome Measurement in Single Cells. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 865–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimitou, E.P.; Cheng, A.; Montalbano, A.; Hao, S.; Stoeckius, M.; Legut, M.; Roush, T.; Herrera, A.; Papalexi, E.; Ouyang, Z.; et al. Multiplexed Detection of Proteins, Transcriptomes, Clonotypes and CRISPR Perturbations in Single Cells. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, E.; Lord, C.; Reading, J.; Heubeck, A.T.; Genge, P.C.; Thomson, Z.; Weiss, M.D.A.; Li, X.J.; Savage, A.K.; Green, R.R.; et al. Simultaneous Trimodal Single-Cell Measurement of Transcripts, Epitopes, and Chromatin Accessibility Using TEA-Seq. eLife 2021, 10, e63632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimitou, E.P.; Lareau, C.A.; Chen, K.Y.; Zorzetto-Fernandes, A.L.; Hao, Y.; Takeshima, Y.; Luo, W.; Huang, T.S.; Yeung, B.Z.; Papalexi, E.; et al. Scalable, Multimodal Profiling of Chromatin Accessibility, Gene Expression and Protein Levels in Single Cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1246–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A.; Kong, Y.; Chen, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z. Advancements and Applications of Single-Cell Multi-Omics Techniques in Cancer Research: Unveiling Heterogeneity and Paving the Way for Precision Therapeutics. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 37, 101589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriques, S.G.; Stickels, R.R.; Goeva, A.; Martin, C.A.; Murray, E.; Vanderburg, C.R.; Welch, J.; Chen, L.M.; Chen, F.; Macosko, E.Z. Slide-Seq: A Scalable Technology for Measuring Genome-Wide Expression at High Spatial Resolution. Science 2019, 363, 1463–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickels, R.R.; Murray, E.; Kumar, P.; Li, J.; Marshall, J.L.; Di Bella, D.J.; Arlotta, P.; Macosko, E.Z.; Chen, F. Highly Sensitive Spatial Transcriptomics at Near-Cellular Resolution with Slide-SeqV2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; DiStasio, M.; Su, G.; Asashima, H.; Enninful, A.; Qin, X.; Deng, Y.; Nam, J.; Gao, F.; Bordignon, P.; et al. High-Plex Protein and Whole Transcriptome Co-Mapping at Cellular Resolution with Spatial CITE-Seq. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1405–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Roumeliotis, T.I.; Chang, Y.H.; Chen, C.T.; Han, C.L.; Lin, M.H.; Chen, H.W.; Chang, G.C.; Chang, Y.L.; Wu, C.T.; et al. Proteogenomics of Non-Smoking Lung Cancer in East Asia Delineates Molecular Signatures of Pathogenesis and Progression. Cell 2020, 182, 226–244.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, J.P.; van Buggenum, J.A.G.; Tanis, S.E.J.; Hogeweg, M.; Heuts, B.M.H.; Muraro, M.J.; Elze, L.; Rivello, F.; Rakszewska, A.; van Oudenaarden, A.; et al. Combined Quantification of Intracellular (Phospho-)Proteins and Transcriptomics from Fixed Single Cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argelaguet, R.; Arnol, D.; Bredikhin, D.; Deloro, Y.; Velten, B.; Marioni, J.C.; Stegle, O. MOFA+: A Statistical Framework for Comprehensive Integration of Multi-Modal Single-Cell Data. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Stuart, T.; Kowalski, M.H.; Choudhary, S.; Hoffman, P.; Hartman, A.; Srivastava, A.; Molla, G.; Madad, S.; Fernandez-Granda, C.; et al. Dictionary Learning for Integrative, Multimodal and Scalable Single-Cell Analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 42, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Strengths | Limitations | Role in Target Discovery | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat | Preprocessing, clustering, integration | Widely used, rich ecosystem, strong multimodal support | Memory-intensive on very large objects | Defines subpopulations for DGE and pathway analysis leading to candidate targets | R |

| Scanpy | End-to-end single-cell analysis at scale | Scales to millions of cells; integrates with scverse tools | Visualization less turn-key than Seurat | Same as Seurat; scalable for multi-sample screens | Python |

| scCancer | Cancer-oriented scRNA-seq workflows | Cancer-specific annotations; automated HTML reports | Less flexible beyond oncology use cases | Separates malignant/non-malignant cells; supports target prioritization in tumor contexts | R |

| Monocle | Trajectory inference & pseudotime | Mature ecosystem; well-documented | Sensitive to noise; multiple versions (v2 vs. v3) | Reveals lineage-specific programs and resistance trajectories informing targets | R |

| Slingshot | Trajectory inference (branching lineages) | Robust lineage reconstruction; Bioconductor integration | Focused scope (trajectory module) | Identifies dynamic states associated with therapy response/targets | R |

| CellPhoneDB | Ligand–receptor inference & CCI analysis | Curated human LR database; new scoring & TF module | Restricted to known interactions; database-centric | Highlights signaling pathways & immunotherapy target candidates | Python |

| NicheNet | Ligand-target modeling using prior signaling/GRNs | Predicts downstream target genes; strong Seurat interop | Requires curated priors; R-centric | Prioritizes ligands/receptors and downstream targets in receiver cells | R |

| LACE | Longitudinal phylogeny from single-cell mutations | R package + Shiny GUI; longitudinal clonal trees | Requires multiple time points, computationally heavy | Identifies mutation-driven targets/resistance biomarkers over time | R |

| Canopy | Bayesian tumor phylogeny from SNV/CNA | Integrates SNAs & CNAs; outputs multiple tree configs | Requires careful input prep; model complexity | Links genetic alterations to vulnerabilities for drug target nomination | R |

| LiBIO | ML framework for longitudinal biomarker discovery | Cross-cancer generalizability; strong AUCs reported | No public package identified; study-specific | Predictive biomarker development for Immune checkpoint blockade response | - |

| scVelo | RNA velocity (steady-state & dynamical models) | Dynamical modeling; integrates with Scanpy | Needs spliced/unspliced layers; quality-sensitive | Identifies dynamic programs & putative drivers/states for targeting | Python |

| BayVel | Bayesian framework for RNA velocity estimation | Adds uncertainty quantification | Implementation details not publicly released—not yet peer reviewed | Improves confidence in velocity-based prioritization | Julia |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tarozzi, M.; Derus, N.R.; Polizzi, S.; Sala, C.; Castellani, G. Single-Cell Transcriptomics and Computational Frameworks for Target Discovery in Cancer. Targets 2026, 4, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/targets4010006

Tarozzi M, Derus NR, Polizzi S, Sala C, Castellani G. Single-Cell Transcriptomics and Computational Frameworks for Target Discovery in Cancer. Targets. 2026; 4(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/targets4010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarozzi, Martina, Nicolas Riccardo Derus, Stefano Polizzi, Claudia Sala, and Gastone Castellani. 2026. "Single-Cell Transcriptomics and Computational Frameworks for Target Discovery in Cancer" Targets 4, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/targets4010006

APA StyleTarozzi, M., Derus, N. R., Polizzi, S., Sala, C., & Castellani, G. (2026). Single-Cell Transcriptomics and Computational Frameworks for Target Discovery in Cancer. Targets, 4(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/targets4010006