The Kappa Opioid Receptor: Candidate Pharmacotherapeutic Target for Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Multiple Sclerosis Therapeutics

3. Kappa Opioid Receptor Agonists in Multiple Sclerosis Models

4. Mechanism for KOR Agonist Effects on MS Models and Remyelination

5. Considerations for KOR Agonists as Pharmacotherapeutics

6. Summary and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGinley, M.P.; Goldschmidt, C.H.; Rae-Grant, A.D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree BA, C.; Arnold, D.L.; Chataway, J.; Chitnis, T.; Fox, R.J.; Pozo Ramajo, A.; Murphy, N.; Lassmann, H. Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis: New Insights. Neurology 2021, 97, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch-Henriksen, N.; Magyari, M. Apparent changes in the epidemiology and severity of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Vidal-Jordana, A.; Montalban, X. Multiple sclerosis: Clinical aspects. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2018, 31, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, M.; Goldman, M.D. Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Multiple Sclerosis. Continuum 2022, 28, 988–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Y.N. Ocrelizumab: A Review in Multiple Sclerosis. Drugs 2022, 82, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, L.; Longbrake, E.E.; Coyle, P.K.; Hendin, B.; Vollmer, T. High-Efficacy Therapies for Treatment-Naïve Individuals with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2022, 36, 1285–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.W.; Kaur, S.; Sage, K.; Kim, J.; Levesque-Roy, M.; Cerchiaro, G.; Yong, V.W.; Cutter, G.R.; Metz, L.M. Hydroxychloroquine for Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 90, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierhansl, L.; Hartung, H.P.; Aktas, O.; Ruck, T.; Roden, M.; Meuth, S.G. Thinking outside the box: Non-canonical targets in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 578–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galoppin, M.; Kari, S.; Soldati, S.; Pal, A.; Rival, M.; Engelhardt, B.; Astier, A.; Thouvenot, E. Full spectrum of vitamin D immunomodulation in multiple sclerosis: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Brain Commun. 2022, 4, fcac171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogha, A.; D’Rozario, M.; Monk, K.R. G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Myelinating Glia. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 37, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalefield, M.L.; Scouller, B.; Bibi, R.; Kivell, B.M. The Kappa Opioid Receptor: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Multiple Pathologies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 837671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, B.; Butelman, E.R.; Kreek, M.J. Endogenous opioid system in addiction and addiction-related behaviors. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 13, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginbotham, J.A.; Markovic, T.; Massaly, N.; Morón, J.A. Endogenous opioid systems alterations in pain and opioid use disorder. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1014768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.K.; Smith, C.M.; Rahmatullah, M.; Nissapatorn, V.; Wilairatana, P.; Spetea, M.; Gueven, N.; Dietis, N. Opioid Analgesia and Opioid-Induced Adverse Effects: A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plein, L.M.; Rittner, H.L. Opioids and the immune system—Friend or foe. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 2717–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corder, G.; Castro, D.C.; Bruchas, M.R.; Scherrer, G. Endogenous and Exogenous Opioids in Pain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 41, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herz, A. Opioid reward mechanisms: A key role in drug abuse? Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1998, 76, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, A.; Kehner, G.B.; Inan, S. Targeting Itch with Ligands Selective for κ Opioid Receptors. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2015, 226, 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- Inui, S. Nalfurafine hydrochloride for the treatment of pruritus. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2012, 13, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thokala, P.; Hnynn Si, P.E.; Hernandez Alava, M.; Sasso, A.; Schaufler, T.; Soro, M.; Fotheringham, J. Cost Effectiveness of Difelikefalin Compared to Standard Care for Treating Chronic Kidney Disease Associated Pruritus (CKD-aP) in People with Kidney Failure Receiving Haemodialysis. Pharmacoeconomics 2023, 41, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworsky-Fried, Z.; Chadwick, C.I.; Kerr, B.J.; Taylor, A.M.W. Multiple Sclerosis and the Endogenous Opioid System. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 741503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.L.; Alley, J.F.; Wellman, L.; Beitz, A.J. Decreased spinal cord opioid receptor mRNA expression and antinociception in a Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus model of multiple sclerosis. Brain Res. 2008, 1191, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Radulović, J.; Djergović, D.; Miljević, C.; Janković, B.D. kappa-Opioid receptor functions: Possible relevance to experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Neuroimmunomodulation 1994, 1, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.D.; Karpus, W.J. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the mouse. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 2007, 15, 15.11.11–15.11.18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Duan, Y.; Wei, W.; Cai, Y.; Chai, H.; Lv, J.; Du, X.; Zhu, J.; Xie, X. Kappa opioid receptor activation alleviates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and promotes oligodendrocyte-mediated remyelination. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, F.; Mayoral, S.R.; Nobuta, H.; Wang, F.; Desponts, C.; Lorrain, D.S.; Xiao, L.; Green, A.J.; Rowitch, D.; Whistler, J.; et al. Identification of the Kappa-Opioid Receptor as a Therapeutic Target for Oligodendrocyte Remyelination. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 7925–7935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangherlini, G.; Kalinin, D.V.; Schepmann, D.; Che, T.; Mykicki, N.; Ständer, S.; Loser, K.; Wünsch, B. Development of Novel Quinoxaline-Based κ-Opioid Receptor Agonists for the Treatment of Neuroinflammation. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, L.; Al Abadey, A.; Robichon, K.; Templeton, N.; Prisinzano, T.E.; Kivell, B.M.; La Flamme, A.C. Nalfurafine reduces neuroinflammation and drives remyelination in models of CNS demyelinating disease. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2021, 10, e1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, K.F.; Robichon, K.; Templeton, N.; Denny, L.; Al Abadey, A.; Luo, D.; Prisinzano, T.E.; La Flamme, A.C.; Kivell, B.M. The Salvinorin Analogue, Ethoxymethyl Ether Salvinorin B, Promotes Remyelination in Preclinical Models of Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 782190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thell, K.; Hellinger, R.; Sahin, E.; Michenthaler, P.; Gold-Binder, M.; Haider, T.; Kuttke, M.; Liutkevičiūtė, Z.; Göransson, U.; Gründemann, C.; et al. Oral activity of a nature-derived cyclic peptide for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 3960–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamura, S.; Matsuo, N.; Nagayasu, K.; Shirakawa, H.; Kaneko, S. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein 35-55 (MOG 35-55)-induced Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis: A Model of Chronic Multiple Sclerosis. Bio Protoc. 2019, 9, e3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonin, F.; Valverde, O.; Smadja, C.; Slowe, S.; Kitchen, I.; Dierich, A.; Le Meur, M.; Roques, B.P.; Maldonado, R.; Kieffer, B.L. Disruption of the kappa-opioid receptor gene in mice enhances sensitivity to chemical visceral pain, impairs pharmacological actions of the selective kappa-agonist U-50,488H and attenuates morphine withdrawal. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praet, J.; Guglielmetti, C.; Berneman, Z.; Van der Linden, A.; Ponsaerts, P. Cellular and molecular neuropathology of the cuprizone mouse model: Clinical relevance for multiple sclerosis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 47, 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schattauer, S.S.; Kuhar, J.R.; Song, A.; Chavkin, C. Nalfurafine is a G-protein biased agonist having significantly greater bias at the human than rodent form of the kappa opioid receptor. Cell Signal 2017, 32, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruchas, M.R.; Chavkin, C. Kinase cascades and ligand-directed signaling at the kappa opioid receptor. Psychopharmacology 2010, 210, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.D.; Reed, B.; Erazo, J.; Ben-Ezra, A.; Kreek, M.J. Signaling Properties of Structurally Diverse Kappa Opioid Receptor Ligands: Toward in Vitro Models of in Vivo Responses. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 3590–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, C.; Werfel, E.; Schepmann, D.; Wünsch, B. Combination of cyclohexane and piperazine based κ-opioid receptor agonists: Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of trans,trans-configured perhydroquinoxalines. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 3316–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gründemann, C.; Thell, K.; Lengen, K.; Garcia-Käufer, M.; Huang, Y.H.; Huber, R.; Craik, D.J.; Schabbauer, G.; Gruber, C.W. Cyclotides Suppress Human T-Lymphocyte Proliferation by an Interleukin 2-Dependent Mechanism. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratspahić, E.; Tomašević, N.; Nasrollahi-Shirazi, S.; Gattringer, J.; Emser, F.S.; Freissmuth, M.; Gruber, C.W. Plant-Derived Cyclotides Modulate κ-Opioid Receptor Signaling. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2238–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Colgrave, M.L.; Daly, N.L.; Keleshian, A.; Martinac, B.; Craik, D.J. The biological activity of the prototypic cyclotide kalata b1 is modulated by the formation of multimeric pores. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 20699–20707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradl, M.; Lassmann, H. Oligodendrocytes: Biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Mei, F. Kappa opioid receptor and oligodendrocyte remyelination. Vitam. Horm. 2019, 111, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miron, V.E.; Kuhlmann, T.; Antel, J.P. Cells of the oligodendroglial lineage, myelination, and remyelination. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2011, 1812, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moharregh-Khiabani, D.; Blank, A.; Skripuletz, T.; Miller, E.; Kotsiari, A.; Gudi, V.; Stangel, M. Effects of fumaric acids on cuprizone induced central nervous system de- and remyelination in the mouse. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopher, G.; Viktor, S.; Peter, L.; Gloria, M.; Andrew, C.; Yong, V.W.; Samuel, W. White Matter Plasticity and Enhanced Remyelination in the Maternal CNS. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 1812. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, S.; Marie-Stéphane, A.; Frédéric, N.; Aurélie, W.; Bernard, Z.; Catherine, L. Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor (CNTF) Enhances Myelin Formation: A Novel Role for CNTF and CNTF-Related Molecules. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 9221. [Google Scholar]

- Roullet, E.; Verdier-Taillefer, M.H.; Amarenco, P.; Gharbi, G.; Alperovitch, A.; Marteau, R. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: A longitudinal study of 125 remittent patients. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1993, 56, 1062–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voldsbekk, I.; Barth, C.; Maximov, I.I.; Kaufmann, T.; Beck, D.; Richard, G.; Moberget, T.; Westlye, L.T.; de Lange, A.G. A history of previous childbirths is linked to women’s white matter brain age in midlife and older age. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2021, 42, 4372–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’hooghe, M.B.; Nagels, G.; Uitdehaag, B.M.J. Long-term effects of childbirth in MS. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2010, 81, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, W.K.; Kayla, S.; Sharanjit, K.; Janet, K.; Graziela, C.; Yong, V.W.; Gary, R.C.; Luanne, M.M. Repurposing Domperidone in Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 2021, 96, e2313. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, D.A.; Strawderman, E.; Rodriguez, A.; Hoang, R.; Schneider, C.L.; Haber, S.; Chernoff, B.L.; Shafiq, I.; Williams, Z.R.; Vates, G.E.; et al. Empty Sella Syndrome as a Window into the Neuroprotective Effects of Prolactin. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 680602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michele, B.; Martha, P.-G.; Stephanie, M.; Sunduz, K.; Giulio, T.; Chiara, C. Effects of Sleep and Wake on Oligodendrocytes and Their Precursors. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 14288. [Google Scholar]

- Linkowski, P.; Spiegel, K.; Kerkhofs, M.; L’Hermite-Balériaux, M.; Van Onderbergen, A.; Leproult, R.; Mendlewicz, J.; Van Cauter, E. Genetic and environmental influences on prolactin secretion during wake and during sleep. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 274, E909–E919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, M.; Musio, S.; Abou-Hamdan, M.; Binart, N.; Pedotti, R. Prolactin is not required for the development of severe chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 2082–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicotte, N.L.; Liva, S.M.; Klutch, R.; Pfeiffer, P.; Bouvier, S.; Odesa, S.; Wu, T.C.J.; Voskuhl, R.R. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with the pregnancy hormone estriol. Ann. Neurol. 2002, 52, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.; Reed, B. Recent progress in kappa and mu opioid receptor targeted ligands. Med. Chem. Rev. 2020, 55, 102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, M.E.; Knapp, B.I.; Bidlack, J.M. Unique Pharmacological Properties of the Kappa Opioid Receptor Signaling Through Gαz as Shown with Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Tranfer. Mol. Pharmacol. 2020, 98, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, J.L.; Mello, N.K.; Negus, S.S.; Bidlack, J.M. Kappa opioid agonists as targets for pharmacotherapies in cocaine abuse. Pharm. Acta Helv. 2000, 74, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piercey, M.F.; Lahti, R.A.; Schroeder, L.A.; Einspahr, F.J.; Barsuhn, C. U-50488H, a pure kappa receptor agonist with spinal analgesic loci in the mouse. Life Sci. 1982, 31, 1197–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur, E.; Wright, D.M.; Bouloux, P.M.; Grossman, A. The effects of spiradoline (U-62066E), a kappa-opioid receptor agonist, on neuroendocrine function in man. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997, 120, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, A.; Bartoszyk, G.D.; Bender, H.M.; Gottschlich, R.; Greiner, H.E.; Harting, J.; Mauler, F.; Minck, K.O.; Murray, R.D.; Simon, M.; et al. A pharmacological profile of the novel, peripherally-selective kappa-opioid receptor agonist, EMD 61753. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994, 113, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois, C.; Werfel, E.; Galla, F.; Lehmkuhl, K.; Torres-Gómez, H.; Schepmann, D.; Kögel, B.; Christoph, T.; Straßburger, W.; Englberger, W.; et al. Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of 5-Pyrrolidinylquinoxalines as a Novel Class of Peripherally Restricted κ-Opioid Receptor Agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 6845–6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endoh, T.; Tajima, A.; Izumimoto, N.; Suzuki, T.; Saitoh, A.; Suzuki, T.; Narita, M.; Kamei, J.; Tseng, L.F.; Mizoguchi, H.; et al. TRK-820, a Selective Kappa-Opioid Agonist, Produces Potent Antinociception in Cynomolgus Monkeys. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 85, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, B.L.; Baner, K.; Westkaemper, R.; Siebert, D.; Rice, K.C.; Steinberg, S.; Ernsberger, P.; Rothman, R.B. Salvinorin A: A potent naturally occurring nonnitrogenous kappa opioid selective agonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11934–11939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Daibani, A.; Paggi, J.M.; Kim, K.; Laloudakis, Y.D.; Popov, P.; Bernhard, S.M.; Krumm, B.E.; Olsen RH, J.; Diberto, J.; Carroll, F.I.; et al. Molecular mechanism of biased signaling at the kappa opioid receptor. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, E.L.; Bento, A.F.; Cavalli, J.; Oliveira, S.K.; Schwanke, R.C.; Siqueira, J.M.; Freitas, C.S.; Marcon, R.; Calixto, J.B. Non-clinical studies in the process of new drug development—Part II: Good laboratory practice, metabolism, pharmacokinetics, safety and dose translation to clinical studies. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2016, 49, e5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumada, H.; Miyakawa, H.; Muramatsu, T.; Ando, N.; Oh, T.; Takamori, K.; Nakamoto, H. Efficacy of nalfurafine hydrochloride in patients with chronic liver disease with refractory pruritus: A randomized, double-blind trial. Hepatol. Res. 2017, 47, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipp, M.; Nyamoya, S.; Hochstrasser, T.; Amor, S. Multiple sclerosis animal models: A clinical and histopathological perspective. Brain Pathol. 2017, 27, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peferoen, L.A.; Breur, M.; van de Berg, S.; Peferoen-Baert, R.; Boddeke, E.H.; van der Valk, P.; Pryce, G.; van Noort, J.M.; Baker, D.; Amor, S. Ageing and recurrent episodes of neuroinflammation promote progressive experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in Biozzi ABH mice. Immunology 2016, 149, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüther, B.J.; Scheld, M.; Dreymueller, D.; Clarner, T.; Kress, E.; Brandenburg, L.O.; Swartenbroekx, T.; Hoornaert, C.; Ponsaerts, P.; Fallier-Becker, P.; et al. Combination of cuprizone and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis to study inflammatory brain lesion formation and progression. Glia 2017, 65, 1900–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

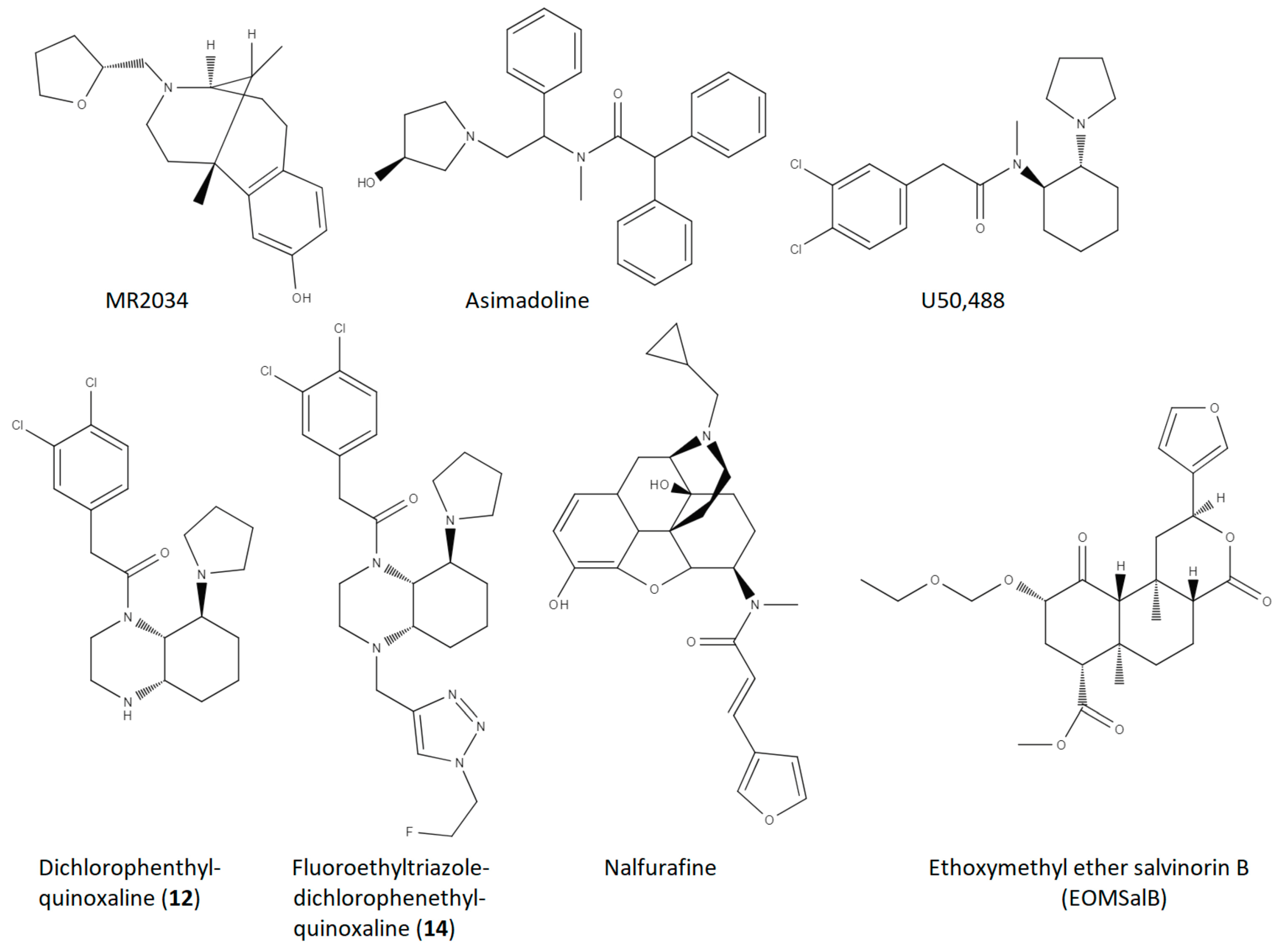

| Compound | Reference | MS Model | Measure | Dose | Approximate Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR2034 | Radulovic et al., 2010 [24] | EAE, Dark August Rats | 1. EAE Score 2. anti-MBP titre 3. histological EAE lesions | 0.2 mg/kg, i.p, 11 days, 1/day | 1. 25–75% ↓ 2. 40% ↓ 3. 70% ↓ |

| Asimadoline | Du et al., 2016 [26] | EAE, C57BL/6 mice | EAE Score | 5 mg/kg, i.p., 22 days, 1/day | 70–90% ↓ |

| U50,488 | Du et al., 2016 [26] | EAE, C57BL/6 mice | 1. EAE Score 2. % demyelination (MBP) 3. NG2 PBMC | 1.6 mg/kg, i.p., 22 days, 1/day | 1. 60–80% ↓ 2. 60% ↓ 3. 50% ↓ |

| U50,488 | Du et al., 2016 [26] | Cuprizone demyelination, C57BL/6 mice | % remyelination | 1.6 mg/kg, i.p., 21 days, 1/day | 200% ↑ |

| U50,488 | Du et al., 2016 [26] | In vitro OPC to OL differentiation | % MBP positive cells | 0.5 µM, 1.0 µM; 5 days | 250% ↑ |

| U50,488 | Mei et al., 2016 [27] | In vitro OPC to OL differentiation | % MBP positive cells | 0.5 µM, 2 days | 300% ↑ |

| U50,488 | Mei et al., 2016 [27] | Lysolecithin demyelination, KOR floxed mice (control) on C57BL/6 background | # myelinated axons in corpus callosum | 10 mg/kg, oral gavage, 10 days, 1/day | 70% ↑ |

| U50,488 | Mei et al., 2016 [27] | In vitro OPC to OL differentiation, human iPSC-derived OPC’s | Ratio of MBP positive cells to O4 positive cells | 1.0 µM, 10 days | 250% ↑ |

| Dichlorophenethyl-quinoxaline (12) | Tangherlini et al., 2019 [28] | EAE, C57BL/6 mice | 1. EAE Score 2. % CD45+ leukocytes (CNS) 3. % IL-17+ of CD4 cells 4. % Foxp3+ Treg of CD4 cells | 2 nmol, i.p., 1–18 days | 1. 20–50% ↓ 2. 80%↓ 3. 60% ↓ 4. 300% ↑ |

| Fluoroethyltriazole Dichlorophenethyl-quinoxaline (14) | Tangherlini et al., 2019 [28] | EAE, C57BL/6 mice | 1. EAE Score 2. % CD45+ leukocytes (CNS) 3. % IL-17+ of CD4 cells 4. % Foxp3+ Treg of CD4 cells | 2 nmol, i.p., 1–18 days | 1. 50–80% ↓ 2. 90%↓ 3. 70% ↓ 4. 400% ↑ |

| Fluoroethyltriazole Dichlorophenethyl-quinoxaline (14) | Tangherlini et al., 2019 [28] | In vitro, human PBMC stimulation | 1. % IFN-γ of DC cells 2. % IFN-γ of T cells 3. IFN-γ levels (medium) 4. IL-10 levels (medium) | 5 µg/mL, 48 h | 1. 50% ↓ 2. 70% ↓ 3. 50% ↓ 4. 100% ↑ |

| Nalfurafine | Denny et al., 2021 [29] | EAE, female C57BL/6 mice | 1. % mice recovered 2. days in recovery 3. # of relapses 4. % myelinated axons | 0.01 mg/kg, i.p., 1/day, 23 days (45 days for measure 4) | 1. 900% ↑ 2. 2000% ↑ 3. 80% ↓ 4. 25% ↑ |

| U50,488 | Denny et al., 2021 [29] | EAE, female C57BL/6 mice | 1. % mice recovered 2. days in recovery 3. # of relapses | 1.6 mg/kg, i.p., 1/day, 23 days | 1. 600% ↑ 2. 1500% ↑ 3. modest, non-significant increase |

| Nalfurafine | Denny et al., 2021 [29] | Cuprizone, female C57BL/6 mice | % myelinated axons, corpus callosum | 0.01 mg/kg, i.p., 1/day, 7 days | 10% ↑ (restored to healthy animal levels) |

| Ethoxymethyl ether salvinorin B (EOMSalB) | Paton et al., 2021 [30] | EAE, female C57BL/6 mice | 1. % mice recovered 2. days in recovery | 0.3 mg/kg, i.p., 1/day, 23 days | 1. 300% ↑ 2. 2000% ↑ |

| U50488 | Paton et al., 2021 [30] | EAE, female C57BL/6 mice | 1. % mice recovered 2. days in recovery | 1.6 mg/kg, i.p., 1/day, 23 days | 1. 200% ↑ 2. 1500% ↑ |

| EOMSalB | Paton et al., 2021 [30] | EAE, female C57BL/6 mice | % myelinated area, cervical spinal cord | 0.3 mg/kg, i.p., 1/day, 44 days | 20% ↑ |

| U50,488 | Paton et al., 2021 [30] | EAE, female C57BL/6 mice | % myelinated area, cervical spinal cord | 1.6 mg/kg, i.p., 1/day, 44 days | 15%↑ |

| EOMSalB | Paton et al., 2021 [30] | Cuprizone, female C57BL/6 mice | # of GST-pi+ nuclei (corpus callosum) | 0.3 mg/kg, i.p., 1/day, 7, 14, or 21 days | 7 days—250% ↑ 14 days—100% ↑ 21 days—no change |

| EOMSalB | Paton et al., 2021 [30] | Cuprizone, female C57BL/6 mice | % myelinated axons, corpus callosum | 0.3 mg/kg, i.p., 1/day, 14 or 35 days | 14 days—nonsignificant 35 days—50% ↑ |

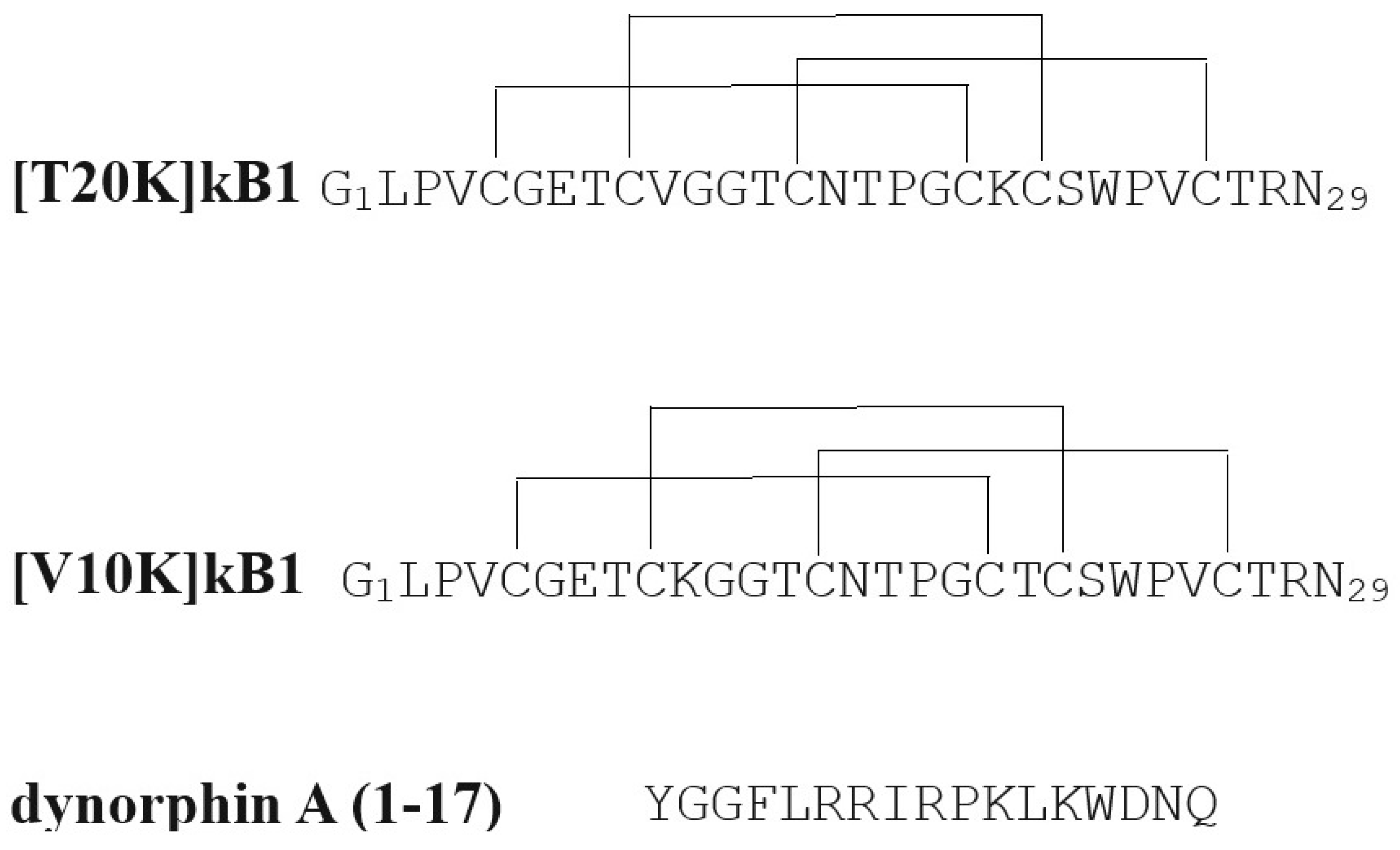

| Cyclotide peptide– [T20K]kalata B1 | Thell et al., 2016 [31] | EAE, C57BL/6 mice | EAE score | 10 mg/kg, i.p, one time, 7 days prior to MOG immunization | 50% ↓ |

| Cyclotide peptide– [T20K]kalata B1 | Thell et al., 2016 [31] | EAE, C57BL/6 mice | EAE score | 10 mg/kg, i.p, one time, 7 days prior to MOG immunization | No effect |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reed, B.; Dutta, S. The Kappa Opioid Receptor: Candidate Pharmacotherapeutic Target for Multiple Sclerosis. Drugs Drug Candidates 2023, 2, 883-897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ddc2040044

Reed B, Dutta S. The Kappa Opioid Receptor: Candidate Pharmacotherapeutic Target for Multiple Sclerosis. Drugs and Drug Candidates. 2023; 2(4):883-897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ddc2040044

Chicago/Turabian StyleReed, Brian, and Surya Dutta. 2023. "The Kappa Opioid Receptor: Candidate Pharmacotherapeutic Target for Multiple Sclerosis" Drugs and Drug Candidates 2, no. 4: 883-897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ddc2040044

APA StyleReed, B., & Dutta, S. (2023). The Kappa Opioid Receptor: Candidate Pharmacotherapeutic Target for Multiple Sclerosis. Drugs and Drug Candidates, 2(4), 883-897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ddc2040044