Associations Between Preschool Bedroom Television and Subsequent Psycho-Social Risks Amplified by Extracurricular Childhood Sport

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

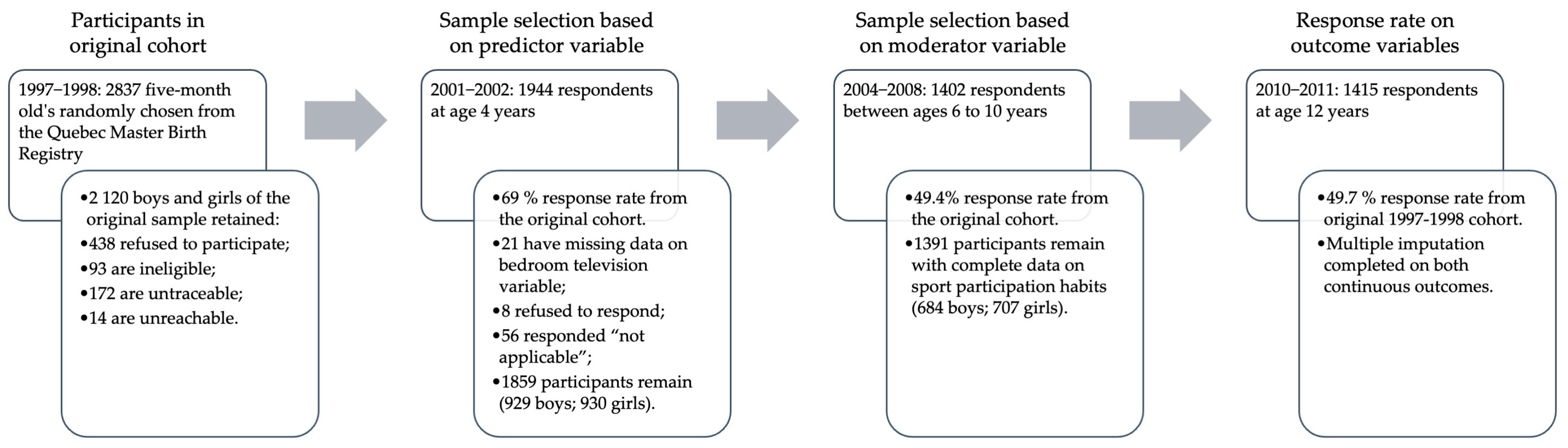

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analytic Strategy

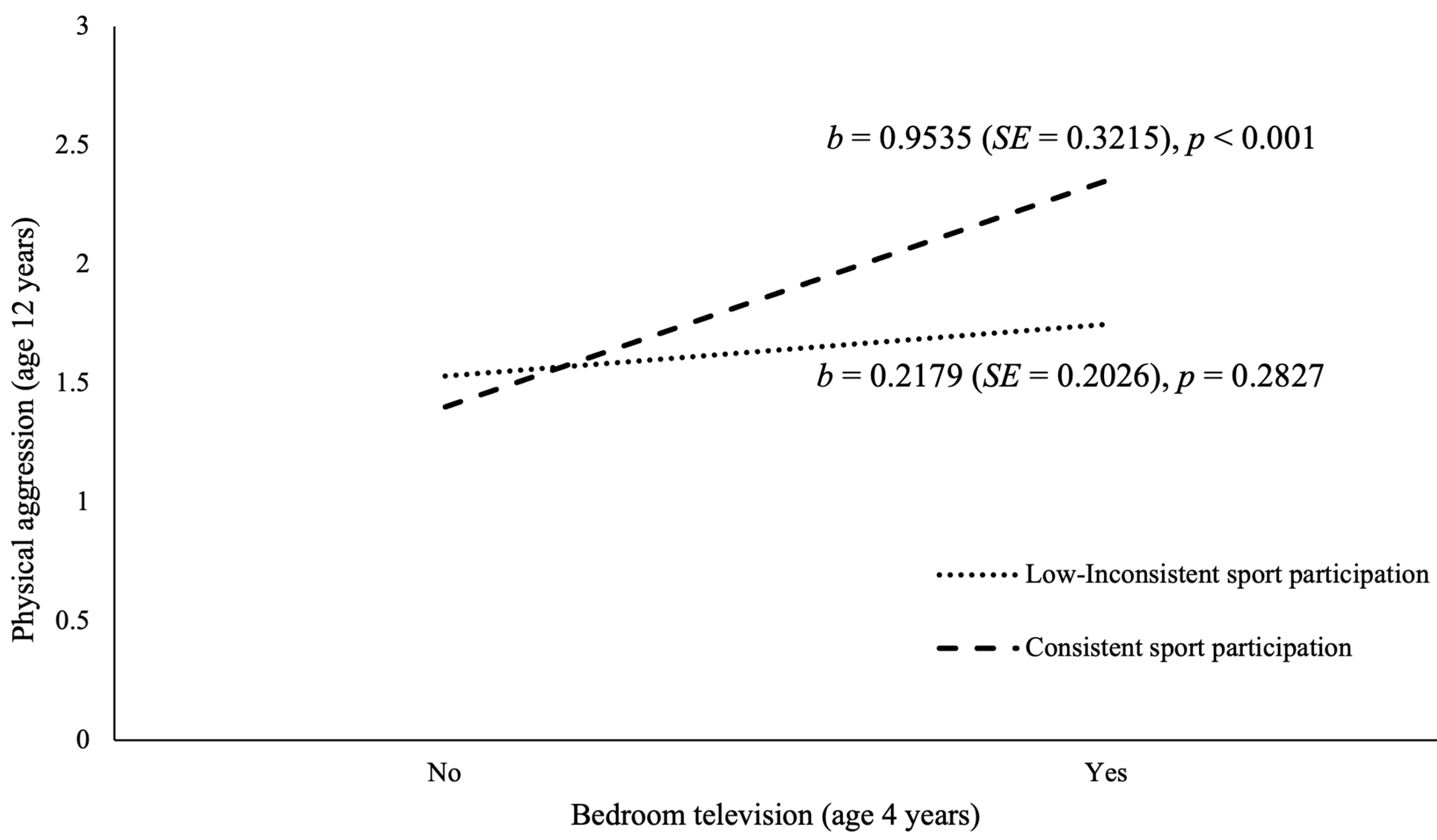

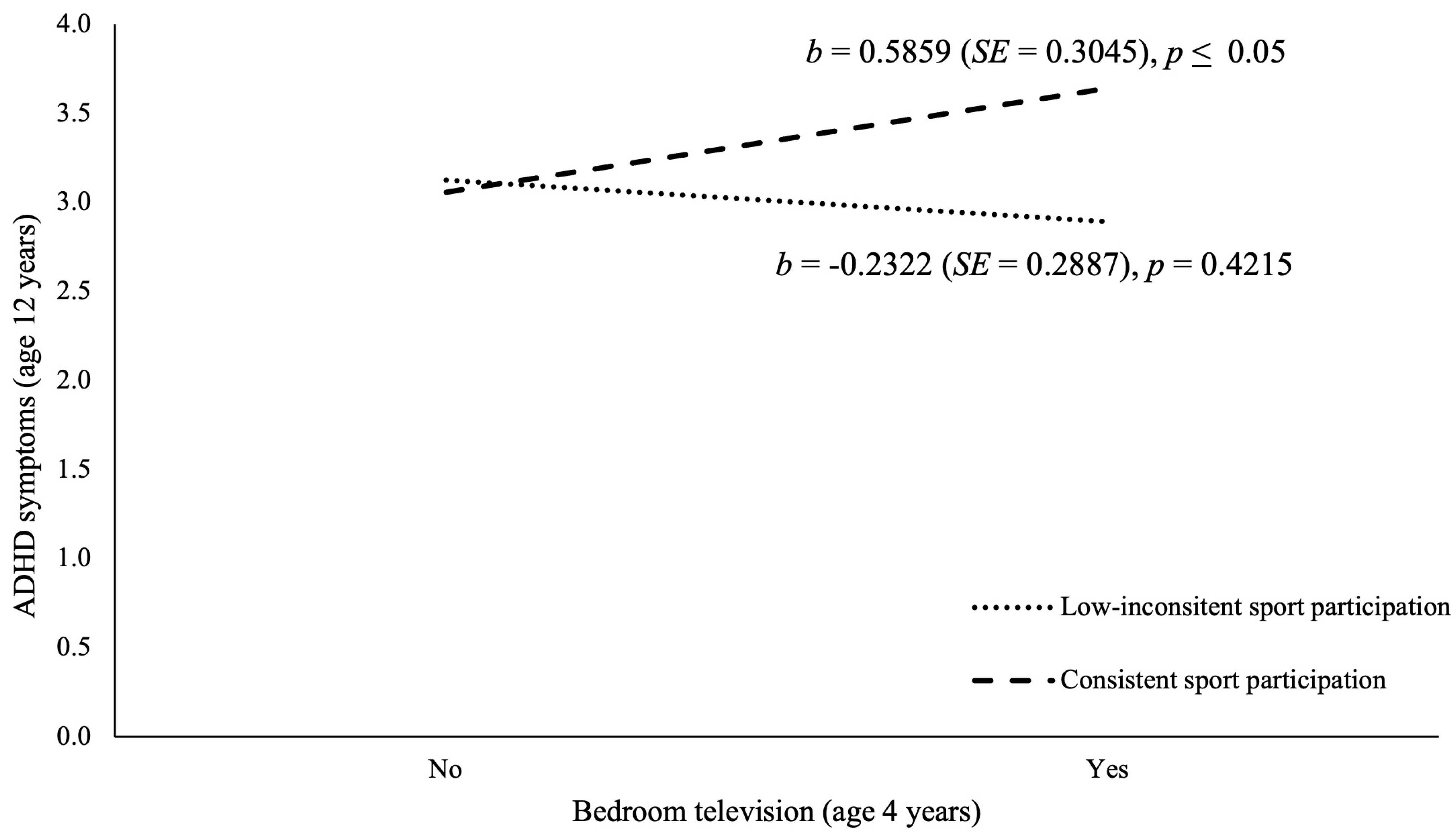

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Attrition Analyses

| Variable | Coding | Source/Instrument | Answer Scale | Example of Questions Asked |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal depressive symptoms (5 months) | Standardized scale 0–10 | Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D) short form [29,30] | Likert scale: (1) Rarely or never to (4) Most of the time or always | “I felt depressed”, “I had restless sleep”, “I cried”, etc. |

| Maternal education (5 months) | Dichotomous: 0 = Higher than high school, 1 = High school or less | Not applicable | Likert scale: (1) No high school diploma to (7) University diploma | “What is the highest level of education you have completed?” |

| Family dysfunction (5 months) | Dichotomous: 0 = Below the median, 1 = Above the median | McMaster Family Functioning Scale [31] | Likert scale: (1) Entirely agree to (4) Entirely disagree | “We are able to make decisions on how to solve our problems together.” |

| Family income (2 years) | Dichotomous: 0 = Above the median, 1 = Below the median | Based on Statistics Canada’s Low-Income Cut-Off (LICO) | 9-point Likert: (1) <$10 k to (9) >$80 k | “Which of the following categories best represents your household’s income?” |

| Child temperament problems (1.5 years) | Dichotomous: 0 = More problematic than median, 1 = Less problematic than median | Infant Characteristics Questionnaire [32] | Likert scales: e.g., (0) Never to (6) 15+ times/day | “On average, how many times per day does your child become fussy and irritable?” |

| Neurocognitive skills (2 years) | Dichotomous: 0 = Above median, 1 = Below median | Imitation Sorting Task [33] | Performance score/task: (0) Failed, (1) Success | Child asked to replicate a demonstrated object-sorting sequence (evaluates working memory) |

| Physical aggression (3.5 years) | Standardized scale 0–10 | Social Behavior Questionnaire [26] | Likert scale: (1) Never or not true to (3) Often or very true | “In the past 3 months, how often has your child been in a fight?” |

| ADHD symptoms (3.5 years) | Standardized scale 0–10 | Social Behavior Questionnaire [26] | Likert scale: (1) Never or not true to (3) Often or very true | “In the past 12 months, how often was the child restless, fidgety, or hyperactive?” |

| Bedroom television (12 years) | Dichotomous: 0 = Yes, 1 = No | Not applicable | Not applicable | “I have the following things in my bedroom: a television.” |

References

- MacDonald, K.B.; Patte, K.A.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Schermer, J.A. Loneliness and Screen Time Usage over a Year. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep for Children Under 5 Years of Age; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/340892 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Eirich, R.; McArthur, B.A.; Anhorn, C.; McGuinness, C.; Christakis, D.A.; Madigan, S. Association of Screen Time with Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems in Children 12 Years or Younger: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, D.A.; Berch, O.N.; Choo, H.; Khoo, A.; Walsh, D.A. Bedroom Media: One Risk Factor for Development. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 2340–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghese, M.M.; Tremblay, M.S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Schuna, J.M.; Leduc, G.; Boyer, C.; LeBlanc, A.G.; Chaput, J.-P. Mediating Role of Television Time, Diet Patterns, Physical Activity and Sleep Duration in the Association between Television in the Bedroom and Adiposity in 10 Year-Old Children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council on Communications and Media; Hill, D.; Ameenuddin, N.; Reid, C.; Yolanda, L.; Cross, C.; Hutchinson, J.; Levine, A.; Boyd, R.; Mendelson, R.; et al. Media and Young Minds. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, L.S.; Gilker Beauchamp, A.; Kosak, L.-A.; Harandian, K.; Longobardi, C.; Dubow, E. Prospective Associations Between Preschool Exposure to Violent Televiewing and Externalizing Behavior in Middle Adolescent Boys and Girls. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2025, 22, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M.L.; Mitchell, K.J.; Oppenheim, J.K. Violent Media in Childhood and Seriously Violent Behavior in Adolescence and Young Adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 71, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohr, B.R.; McGowan, E.C.; Bann, C.; Das, A.; Higgins, R.; Hintz, S.; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Association of High Screen-Time Use with School-Age Cognitive, Executive Function, and Behavior Outcomes in Extremely Preterm Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Hargittai, E.; Neuman, W.R.; Robinson, J.P. Social Implications of the Internet. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 307–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, K.M. Fostering Middle School Students’ Autonomy to Support Motivation and Engagement. Middle Sch. J. 2019, 50, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, B.J.; McLure, F.I.; Koul, R.B. Assessing Classroom Emotional Climate in STEM Classrooms: Developing and Validating a Questionnaire. Learn. Environ. Res. 2021, 24, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M. Concepts and Theories of Human Development, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.L.; Deal, C.J.; Pankow, K. Positive Youth Development Through Sport. In Handbook of Sport Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. PERMA and the Building Blocks of Well-Being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.V.; Sera, F.; Cummins, S.; Flouri, E. Associations between Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Later Mental Health Outcomes in Children: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Månsson, A.G.; Elmose, M.; Dalsgaard, S.; Roessler, K.K. The Influence of Participation in Target-Shooting Sport for Children with Inattentive, Hyperactive and Impulsive Symptoms—A Controlled Study of Best Practice. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Hadwin, J.A. The Roles of Sex and Gender in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. JCPP Adv. 2022, 2, e12059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, A.; McVeigh, J.; Hissen, S.L.; Howie, E.K.; Eastwood, P.R.; Straker, L.; Mori, T.A.; Beilin, L.; Ainslie, P.N.; Green, D.J. Participation in Sport in Childhood and Adolescence: Implications for Adult Fitness. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2021, 24, 908–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M.; Martin, G.N. Gender Differences in Associations between Digital Media Use and Psychological Well-being: Evidence from Three Large Datasets. J. Adolesc. 2020, 79, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfield, S.; Mouzon, D. Gender and Mental Health. In Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health; Aneshensel, C.S., Phelan, J.C., Bierman, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauermeister, J.J.; Shrout, P.E.; Chávez, L.; Rubio-Stipec, M.; Ramírez, R.; Padilla, L.; Anderson, A.; García, P.; Canino, G. ADHD and Gender: Are Risks and Sequela of ADHD the Same for Boys and Girls? J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatr. 2007, 48, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S.M.; Stockdale, L. Growing Up with Grand Theft Auto: A 10-Year Study of Longitudinal Growth of Violent Video Game Play in Adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, C.; Ellis, R.P.; Eyssel, F.; Zou, J.; Schiebinger, L. Sex and Gender Analysis Improves Science and Engineering. Nature 2019, 575, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R.E.; Loeber, R.; Gagnon, C.; Charlebois, P.; Larivée, S.; LeBlanc, M. Disruptive Boys with Stable and Unstable High Fighting Behavior Patterns during Junior Elementary School. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 1991, 19, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brière, F.N.; Imbeault, A.; Goldfield, G.S.; Pagani, L.S. Consistent Participation in Organized Physical Activity Predicts Emotional Adjustment in Children. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 88, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, L.S.; Harandian, K.; Gauthier, B.; Kosak, L.-A.; Necsa, B.; Tremblay, M.S. Middle Childhood Sport Participation Predicts Timely Long-Term Chances of Academic Success in Boys and Girls by Late Adolescence. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2024, 56, 2184–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, A.J.S.; Moullec, G.; Maïano, C.; Layet, L.; Just, J.-L.; Ninot, G. Psychometric Properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in French Clinical and Nonclinical Adults. Rev. Epidemiol. Med. Soc. Sante Publique 2011, 59, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, N.B.; Baldwin, L.M.; Bishop, D.S. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 1983, 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.E.; Freeland, C.A.B.; Lounsbury, M.L. Measurement of Infant Difficultness. Child. Dev. 1979, 50, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, I.E. Measuring the Size of Working Memory in Very Young Children: The Imitation Sorting Task. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1994, 17, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, L.J.; Lu, Z.; Morris, A.R.; Healey, D.M. Preschool Self Regulation Predicts Later Mental Health and Educational Achievement in Very Preterm and Typically Developing Children. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2017, 31, 404–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, A.G.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Barreira, T.V.; Broyles, S.T.; Chaput, J.-P.; Church, T.S.; Fogelholm, M.; Harrington, D.M.; Hu, G.; Kuriyan, R.; et al. Correlates of Total Sedentary Time and Screen Time in 9–11 Year-Old Children around the World: The International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, G.L.d.M.; Araújo, T.L.; Oliveira, L.C.; Matsudo, V.; Fisberg, M. Association between Electronic Equipment in the Bedroom and Sedentary Lifestyle, Physical Activity, and Body Mass Index of Children. J. Pediatr. 2015, 91, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Li, J.; Chen, E.E. Does Screen Media Hurt Young Children’s Social Development? Longitudinal Associations Between Parental Engagement, Children’s Screen Time, and Their Social Competence. Early Educ. Dev. 2024, 35, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdilanita, U.; Ma’mun, A. The Role of Sports Participation on Social Skill Development in Early Childhood and Adolescence. In Proceedings of the International Seminar of Sport and Exercise Science (ISSES 2024), Surabaya, Indonesia, 26–27 June 2024; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S.M.; Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Holmgren, H.G.; Davis, E.J.; Collier, K.M.; Memmott-Elison, M.K.; Hawkins, A.J. A Meta-Analysis of Prosocial Media on Prosocial Behavior, Aggression, and Empathic Concern: A Multidimensional Approach. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 54, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyens, I.; Valkenburg, P.M. Children’s Media Use and Its Relation to Attention, Hyperactivity, and Impulsivity; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, L.; Annink, A.; Visser, K.; Jambroes, M. Facilitating Children’s Club-Organized Sports Participation: Person–Environment Misfits Experienced by Parents from Low-Income Families. Children 2022, 9, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, P. Missing Data and Multiple Imputation. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponti, M. Screen Time and Preschool Children: Promoting Health and Development in a Digital World. Pediatr. Child. Health 2023, 28, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Boys (N = 684) | Girls (N = 707) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Categorical Variables (%) | M (SD) | Categorical Variables (%) | Range | |

| Predictor variable (4 years) | |||||

| Bedroom television | - | ||||

| 0 = No | - | 84.80 | - | 89.00 | |

| 1 = Yes | - | 15.20 | - | 11.00 | |

| Moderator variable (6–10 years) | |||||

| Sport participation trajectory | |||||

| 0 = Low–inconsistent participation | - | 38.90 | - | 40.40 | - |

| 1 = Consistent participation | - | 61.10 | - | 59.60 | - |

| Outcome variables (12 years) | |||||

| Physical aggression | 1.53 (1.38) | - | 0.66 (0.80) | - | 0.00–10.00 |

| ADHD symptoms | 3.10 (1.93) | - | 1.57 (1.29) | - | 0.00–10.00 |

| Pre-existing control variables | |||||

| Maternal depressive symptoms (5 mo) | 1.34 (1.32) | - | 1.27 (1.19) | - | 0.00–10.00 |

| Maternal education (5 mo) | |||||

| 0 = Post-secondary education or above | - | 60.50 | - | 57.30 | - |

| 1 = High-school diploma or below | - | 39.50 | - | 41.70 | - |

| Family dysfunction (5 mo) | |||||

| 0 = Below the median | - | 55.80 | - | 53.20 | - |

| 1 = Above the median | - | 44.20 | - | 45.60 | - |

| Family income (2 years) | |||||

| 0 = Above the median | - | 5.10 | - | 7.80 | - |

| 1 = Below the median | - | 94.90 | - | 90.00 | - |

| Child temperament problems (1.5 years) | |||||

| 0 = Below the median | - | 52.30 | - | 44.40 | - |

| 1 = Above the median | - | 47.70 | - | 39.60 | - |

| Neurocognitive skills (2 years) | |||||

| 0 = Above the median | - | 78.90 | - | 73.10 | - |

| 1 = Below the median | - | 21.10 | - | 18.40 | - |

| Concurrent control variables | |||||

| Physical aggression (3.5 years) | 2.13 (1.37) | - | 1.83 (1.30) | - | 0.00–10.00 |

| ADHD symptoms (3.5 years) | 4.25 (1.99) | - | 3.68 (1.81) | - | 0.00–10.00 |

| Bedroom television (12 years) | |||||

| 0 = No | - | 60.80 | - | 68.30 | - |

| 1 = Yes | - | 39.20 | - | 31.70 | - |

| b (SE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedroom Television (4 Years) | Sport Participation Trajectories (6 to 10 Years) | |||

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | |

| Pre-existing control variables | ||||

| Maternal depressive symptoms (5 mo) | 0.018 (0.011) | −0.003 (0.010) | 0.007 (0.015) | 0.005 (0.016) |

| Maternal education (5 mo) | 0.015 (0.027) | 0.036 (0.024) | −0.253 (0.038) *** | −0.147 (0.039) *** |

| Family dysfunction (5 mo) | 0.020 (0.027) | 0.034 (0.023) | −0.080 (0.037) * | 0.063 (0.038) |

| Family income (2 years) | −0.016 (0.059) | −0.046 (0.060) | 0.252 (0.081) ** | 0.207 (0.100) * |

| Child temperament problems (1.5 years) | 0.002 (0.026) | −0.049 (0.023) * | 0.012 (0.036) | 0.039 (0.037) |

| Neurocognitive skills (2 years) | 0.056 (0.031) | −0.031 (0.027) | 0.053 (0.043) | 0.071 (0.045) |

| Concurrent control variables | ||||

| Physical aggression (3.5 years) | −0.009 (0.010) | −0.023 (0.009) ** | 0.014 (0.013) | 0.000 (0.014) |

| ADHD symptoms (3.5 years) | 0.013 (0.007) * | 0.002 (0.006) | −0.001 (0.009) | −0.012 (0.010) |

| Bedroom television (12 years) | 0.225 (0.027) *** | 0.145 (0.025) *** | −0.137 (0.037) *** | 0.046 (0.041) |

| R2 | 0.132 *** | 0.080 *** | 0.159 *** | 0.064 *** |

| Physical Aggression (Age 12 Years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |||

| b (SE) | 95% CI | b (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Interaction | ||||

| Sport participation trajectory (6–10 years) x Bedroom television (4 years) | 0.736 (0.287) ** | 0.172, 1.299 | 0.342 (0.203) | −0.057, 0.740 |

| Moderator variable | ||||

| Sport participation trajectory (6–10 years) | −0.129 (0.118) | −0.361, 0.102 | −0.191 (0.065) ** | −0.318, −0.062 |

| Predictor variable | ||||

| Bedroom television (4 years) | 0.2179 (0.213) | −0.180, 0.615 | −0.323 (0.156) * | −0.629, −0.017 |

| Pre-existing control variables | ||||

| Maternal depressive symptoms (5 mo) | 0.145 (0.041) *** | 0.064, 0.227 | 0.015 (0.265) | −0.037, 0.066 |

| Maternal education (5 mo) | −0.201 (0.111) | −0.142, 0.016 | 0.191 (0.065) ** | −0.063, 0.319 |

| Family dysfunction (5 mo) | −0.084 (0.107) | −0.106, 0.049 | −0.027 (0.063) | −0.150, 0.097 |

| Family income (2 years) | −0.489 (0.232) | −0.198, −0.014 | −0.393 (0.166) ** | −0.718, −0.067 |

| Child temperament problems (1.5 years) | −0.369 (0.103) *** | −0.218, −0.069 | 0.010 (0.061) | −0.110, 0.130 |

| Neurocognitive skills (2 years) | 0.364 (0.122) ** | 0.032, 0.177 | −0.042 (0.074) | −0.103, 0.187 |

| Concurrent control variables | ||||

| Physical aggression (3.5 years) | 0.192 (0.037) *** | 0.118, 0.263 | 0.073 (0.024) ** | 0.026, 0.119 |

| ADHD symptoms (3.5 years) | - | - | - | - |

| Bedroom television (12 years) | 0.227 (0.115) * | 0.003, 0.163 | −0.012 (0.070) | −0.150, 0.126 |

| R2 | 0.1334 *** | 0.0609 *** | ||

| ADHD Symptoms (Age 12 Years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |||

| b (SE) | 95% CI | b (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Interaction | ||||

| Sport participation trajectory (6–10 years) x Bedroom television (4 years) | 0.818 (0.409) * | 0.150, 1.621 | 0.368 (0.318) | −0.256, 0.993 |

| Moderator variable | ||||

| Sport participation trajectory (6–10 years) | −0.006 (0.168) | −0.397, 0.263 | −0.329 (0.102) *** | −0.529, −0.128 |

| Predictor variable | ||||

| Bedroom television (4 years) | −0.232 (0.288) | −0.798, 0.334 | −0.087 (0.243) | −0.565, 0.390 |

| Pre-existing control variables | ||||

| Maternal depressive symptoms (5 mo) | 0.152 (0.059) ** | 0.027, 0.194 | 0.024 (0.042) | −0.058, 0.1053 |

| Maternal education (5 mo) | 0.190 (0.157) | −0.031, 0.130 | 0.263 (0.102) ** | 0.062, 0.463 |

| Family dysfunction (5 mo) | −0.081 (0.152) | −0.100, 0.057 | −0.056 (0.099) | −0.250, 0.138 |

| Family income (2 years) | 0.642 (0.330) | −0.000, 0.185 | −0.856 (0.259) *** | −1.365, −0.346 |

| Child temperament problems (1.5 years) | −0.339 (0.143) * | −0.164, −0.015 | −0.038 (0.094) | −0.223, 0.147 |

| Neurocognitive skills (2 years) | 0.186 (0.174) | −0.033, 0.113 | 0.377 (0.116) *** | 0.149, 0.603 |

| Concurrent control variables | ||||

| Physical aggression (3.5 years) | - | - | - | - |

| ADHD symptoms (3.5 years) | −0.818 (0.409) * | 0.152, 0.305 | 0.118 (0.026) *** | 0.067, 0.169 |

| Bedroom television (12 years) | 0.304 (0.159) | −0.002, 0.161 | 0.191 (0.110) | −0.025, 0.406 |

| R2 | 0.1029 *** | 0.1097 *** | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Necsa, B.; Harandian, K.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Dubow, E.F.; Pagani, L.S. Associations Between Preschool Bedroom Television and Subsequent Psycho-Social Risks Amplified by Extracurricular Childhood Sport. Future 2025, 3, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3040019

Necsa B, Harandian K, Fitzpatrick C, Dubow EF, Pagani LS. Associations Between Preschool Bedroom Television and Subsequent Psycho-Social Risks Amplified by Extracurricular Childhood Sport. Future. 2025; 3(4):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3040019

Chicago/Turabian StyleNecsa, Béatrice, Kianoush Harandian, Caroline Fitzpatrick, Eric F. Dubow, and Linda S. Pagani. 2025. "Associations Between Preschool Bedroom Television and Subsequent Psycho-Social Risks Amplified by Extracurricular Childhood Sport" Future 3, no. 4: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3040019

APA StyleNecsa, B., Harandian, K., Fitzpatrick, C., Dubow, E. F., & Pagani, L. S. (2025). Associations Between Preschool Bedroom Television and Subsequent Psycho-Social Risks Amplified by Extracurricular Childhood Sport. Future, 3(4), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/future3040019