Abstract

Youth use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes or vaping) has skyrocketed in recent years, resulting in a youth vaping epidemic. To combat this epidemic, a coalition of U.S.-based researchers created the Rapidly Advancing Discovery to Arrest the Outbreak of Youth Vaping (VapeRace) Center to stop youth e-cigarette use through integration of research across basic, clinical, behavioral, and population-based domains. Because most research on youth vaping is researcher-driven, the VapeRace Community Engagement and Research Translation (CERT) Core was created to facilitate stakeholder input and engagement with Center activities to develop partnerships between VapeRace researchers, youth, and the community. To help achieve these goals, a VapeRace Youth Advisory Council (YAC) was formed. This article describes the development and implementation of the VapeRace YAC, details its outcomes, and offers lessons learned and future recommendations for similar youth advisory groups.

1. Introduction

The use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) among youth has increased dramatically since their introduction to the U.S. marketplace in 2007. There was a 900% increase in e-cigarette use (or vaping) among youth between 2011 and 2015, and e-cigarettes surpassed combustible cigarettes as the most used tobacco product among youth in 2014 [1]. As a result, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory in 2018 labeling these trends a youth vaping epidemic [2].

In 2023, estimates from the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) indicated that 12.6% of high school students currently use e-cigarettes, and of those, 25% report daily use [3]. Although the most recent NYTS data from 2024 revealed a drop in use rates (i.e., to 7.8% among high school students with 29.7% of these youth reporting daily use), the prevalence remains a public health concern [4]. These high prevalence rates have been driven, in part, by beliefs that e-cigarettes are less harmful than combustible cigarettes [5,6]. Unfortunately, mounting evidence indicates that e-cigarettes pose significant health risks, including impaired immune system and lung function and increased risk for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases [7,8,9,10,11,12]. E-cigarettes also contain nicotine, which can interfere with normal brain development [1]. Since the adolescent brain is still developing, it is more vulnerable to the negative effects of nicotine exposure, putting youth e-cigarette users at greater risk of nicotine dependence as well as reduced impulse control and deficits in attention and cognition [1]. Given the array of significant health risks, we face an urgent need to deter e-cigarette use among youth.

The Rapidly Advancing Discovery to Arrest the Outbreak of Youth Vaping (VapeRace) Center was created by researchers in the U.S. to address this critical need. Funded by the American Heart Association’s End Nicotine Addiction in Children and Teens (ENACT) initiative, the VapeRace Center’s mission is to stop youth e-cigarette use through the integration of research across basic, clinical, behavioral, and population-based domains. The VapeRace Center is tasked primarily with three integrated projects: (1) identifying the toxicity of e-cigarette constituents using human induced pluripotent stem cell derived organoids to model growing organs; (2) evaluating the cardiovascular impact of e-cigarette use; and (3) creating a virtual reality-based e-cigarette cessation program for youth. These projects are supported and informed by the Community Engagement and Research Translation (CERT) Core, whose goal is to facilitate stakeholder input and engagement with Center activities to develop partnerships between VapeRace researchers, youth, and the community. In particular, the CERT Core engaged youth to ensure their perspective was represented and incorporated into VapeRace’s work.

Most research on youth e-cigarette use is researcher-driven, gathering information about adolescents rather than working with and learning from adolescents. Meaningfully engaging youth is critically important for creating relevant and effective interventions and policies to successfully address the youth vaping epidemic. One important youth engagement strategy is the creation of a youth advisory board or youth advisory council (YAC) to provide youth with opportunities to share their ideas and perspectives on key issues, especially ones that affect them [13,14]. YACs recognize that youth have unique expertise and knowledge that can guide policies and practices as well as program design and implementation [14,15]. To promote success, YACs must: (1) be youth-led; (2) have consistent, structured meetings; (3) engage in community-building activities; (4) be a safe space; and (5) provide the opportunity to participate in meaningful projects [16]. Recent years have seen growing interest in the use of YACs to inform health-related research [17,18,19,20]; however, to our knowledge, there is only one published study on YACs focused on youth vaping. England and colleagues [21] worked with a YAC as part of a larger project to develop an anti-vaping public health campaign. YAC members discussed perceptions of vaping among themselves and their peers and worked with the research team in an iterative fashion to create the health campaign materials. Highlighting the importance of working with and learning from teens, the authors noted that YAC input was critical, as YAC members’ preferences differed substantially from those of the adults working on the project [21]. However, there is no published work describing the process of creating a YAC focused on youth vaping. Therefore, the goal of the present work is to describe the development and implementation of the VapeRace YAC, detail its outcomes, and offer lessons learned and future recommendations for similar youth advisory groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment

The VapeRace YAC’s mission was to inform peers, inspire communities, and take action to end youth vaping. As described above, CERT Core personnel, consisting of three university professors, six graduate students, and two undergraduate student volunteers, facilitated connections between the Center’s researchers, youth, and other stakeholders, as well as coordinated YAC’s development and work. To disseminate information about the VapeRace YAC, we developed a website, which included information about vaping, the VapeRace Center, YAC membership and expectations, and the YAC application. We also created a social media presence on common platforms to assist with recruitment and later to promote YAC members and their work. To participate in the YAC, youth were required to be in 8th–12th grade in the U.S. and agree to attend and participate in monthly, online meetings during the school year.

Several methods were used to recruit YAC participants, including posting on VapeRace YAC social media platforms, circulating recruitment materials to middle and high school teachers and VapeRace Center investigators, and word of mouth. Because the VapeRace Center included researchers from several universities, social media posting, distribution via teacher networks, and word of mouth outreach covered several geographical areas. We also utilized networks from other current and past research projects as well as additional professional networks to help share the invitation to apply. Recruitment was aided by an electronic and hardcopy flyer that provided an overview of VapeRace and YAC and contained a website link for additional information or to apply. To submit an application, interested youth completed an online form, which included general contact information (e.g., name, grade in school, state) and open-ended questions. In responding to the open-ended questions, applicants provided information on their reasons for wanting to join YAC, their overall thoughts on youth vaping, and what they thought that adults should know about youth vaping. Applicants also had the option to write additional comments if they wanted to do so.

2.2. Participation

Information about the demographic characteristics of the two YAC cohorts is presented in Table 1. The first VapeRace YAC cohort, whose work primarily took place during the spring semester of the 2020–2021 school year, consisted of 17 youth (Mage = 15.7 years, 88.2% 10th–12th graders, 76.5% female, 76.5% White) representing four U.S. states. Attendance ranged from 13 to 17 youth at each meeting (M = 14.6), with 76.5% attending all meetings and 88.2% participating in 75% or more of the meetings. The 2021–2022 VapeRace YAC cohort consisted of 22 youth (Mage = 15.6 years, 72.7% 10th–12th graders, 63.6% female, 81.8% White) representing four states. Attendance for the second cohort ranged from 14 to 22 youth at each meeting (M = 16), with 63.6% attending all meetings and 72.7% participating in 75% or more of the meetings.

Table 1.

Sample demographic information.

We employed several strategies to maintain youth engagement and assist with retention. First, we utilized the GroupMe messaging app to facilitate communication between our team and YAC members (e.g., meeting reminders, announcements, timely links related to youth vaping) as well as between the YAC members themselves. Second, we divided YAC members into smaller groups that were paired with two members of our research team as facilitators (either undergraduate or graduate student research assistants). We used these small groups to facilitate discussion during YAC meetings as well as between meetings. This approach facilitated learning and engagement between YAC members as well as between YAC members and facilitators. Third, we posted weekly spotlights of YAC members on the VapeRace YAC social media accounts. Fourth, YAC members could receive volunteer hours for their participation. Also, summer internship opportunities were offered to allow interested YAC members to deepen their knowledge of vaping and continue their involvement with the VapeRace Center. Finally, YAC members received recognition for their contributions (e.g., Leadership Award, superlatives celebration at the final meeting).

2.3. Meeting Format

To facilitate participation by youth across multiple locations, monthly meetings were held on Zoom at a time when all members had completed the school day. Initial meetings focused on rapport building (e.g., ice breakers, small group discussions) and education about the VapeRace Center. Table 2 presents detailed information about each meeting, and Supplemental Figure S1 illustrates the meeting flow model employed. Meetings were facilitated by three faculty members and six graduate student research assistants. After an initial welcome, the first half of most meetings began with a brief educational presentation and group discussion on a vaping-related topic (e.g., health effects). Early in the year, these group discussions often took place in smaller group breakouts (i.e., approximately 4 YAC members in a breakout room) to facilitate participation by all members until greater group cohesion was attained.

Table 2.

YAC monthly meeting agendas.

Periodically, VapeRace Center researchers attended YAC meetings to discuss their work, engage youth in conversation, and obtain youth feedback and input. These visits and periodic guest speakers also served to educate YAC members on recent vaping-related developments as well as to allow the youth to educate researchers and presenters on current vape use and their perspectives on securing change. Typically, the second half of each meeting consisted of small group breakout sessions where YAC members developed and worked on projects related to youth vaping. For these small group sessions, we often used breakout rooms in Zoom. Graduate students were paired with YAC groups and facilitated the conversation, provided resources, and fielded questions. Each group developed action steps needed to reach goals, determined communication methods (e.g., GroupMe) to use outside the monthly meetings, and set deadlines for project components.

3. Results

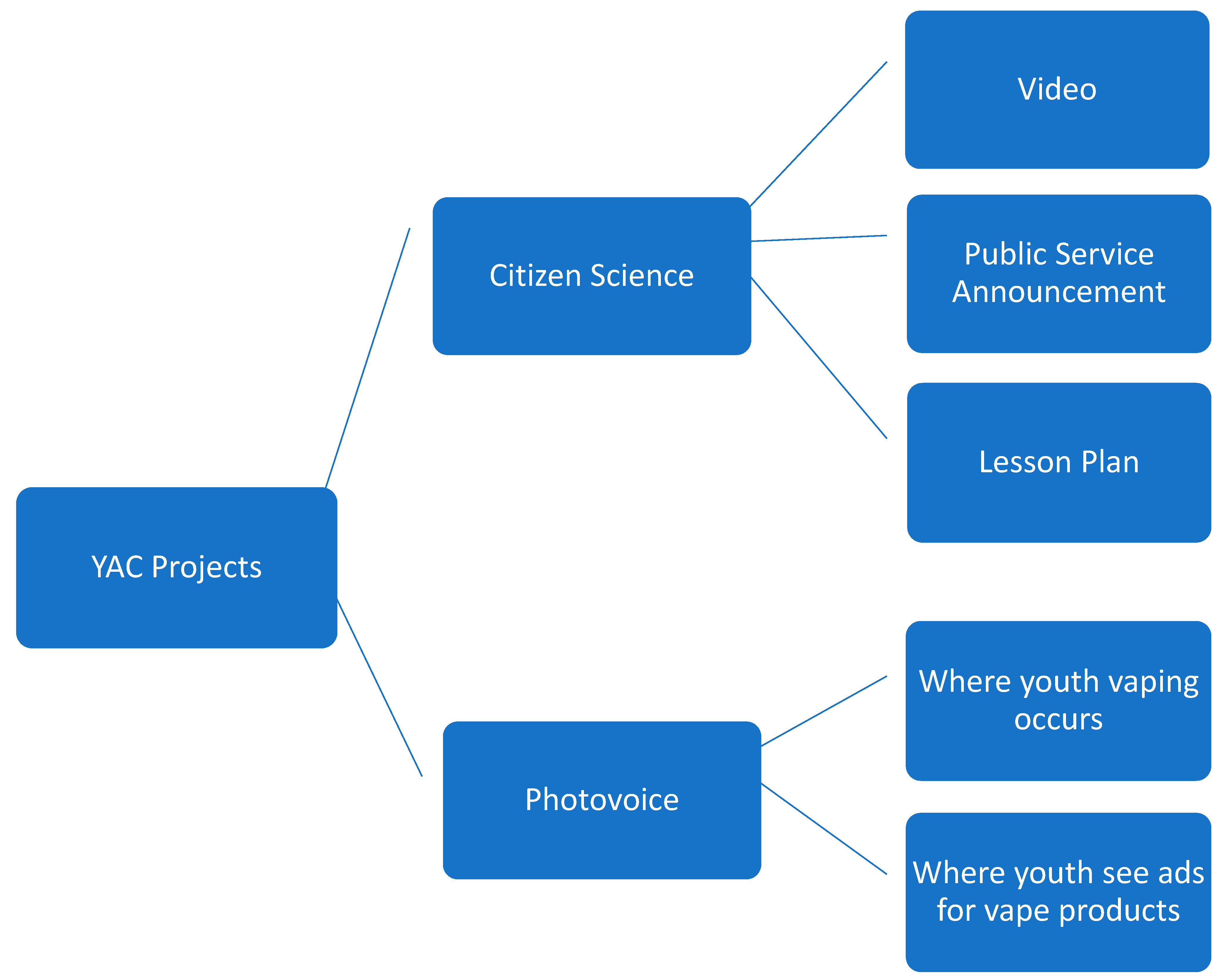

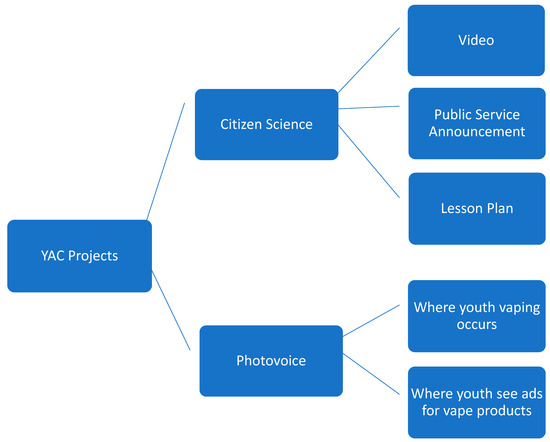

Below we describe the results of YAC’s work as well as lessons learned throughout the experience that will be useful in future youth engagement initiatives. Figure 1 provides an overview of YAC projects.

Figure 1.

Overview of Youth Advisory Council (YAC) results.

3.1. Citizen Science Projects

After spending time learning about the youth vaping epidemic, each YAC cohort engaged in group projects focused on preventing or decreasing youth vaping that would appeal to and engage their peers. The first YAC cohort worked in small groups to create three youth vaping-related projects: (1) a short social media video, (2) a public service announcement (PSA), and (3) school-based lesson plans. The video featured YAC members describing the potential health effects of vaping. Each group member held a vape while sharing information and then transitioned by “dropping” the vape to the next person, with the final speaker dropping the vape into the trash. The PSA began with a screen shot of all group members with a joint voiceover stating, “I know”. Then, each group member shared a fact about vaping (e.g., the number of youth users, chemicals found in vapes, that most youth report not knowing vaping ingredients). The PSA concluded with the group jointly stating, “We know, and now you know”, and provided resources for quitting. The school-based lesson plan incorporated what YAC members saw as vital for reaching their peers and engaging them in taking steps to reduce or eliminate youth vaping. It provided information on current youth vaping, the potential physical and mental health effects of vaping, and reasons to consider quitting vaping or not starting.

The second YAC cohort employed Photovoice to describe youth vaping. Photovoice allowed YAC members to conduct research in their own communities by taking and analyzing photographs for the purpose of social change [22,23]. After training sessions, including objectives, procedures, and ethical considerations, YAC members responded to weekly questions with 5 to 10 photographs (with brief notes about the photos) to visually represent the who, what, when, and where of vaping in their social and personal worlds. Example questions included: Where do you see youth vaping or vaping products? and What signs (e.g., schools, stores, social media, billboards, gas stations, etc.) do you see about vaping or tobacco? Then, YAC members met in small groups with graduate student or faculty facilitators to share and describe their photographs and identify commonalities and points of uniqueness across the group’s photographs. This Photovoice project, named “VapePic”, resulted in the creation of a digital story about youth vaping to showcase the results of the project.

These products were shared in presentations to VapeRace Center researchers and American Heart Association representatives at the end of the year. Additionally, some YAC members presented their work at a meeting of the American Heart Association Tobacco Center for Regulatory Science, and the group’s work has been disseminated in additional ways (e.g., social media, school networks, conferences). In sharing their perspectives on the experience, YAC member comments included the following: “I’m more aware of medical [aspects] of vaping”, [It] “increased my understanding of the dangers of vaping”, It’s [vaping’s] not worth it. It doesn’t give you the self image that you might think it does, and it only leads to harm”, and “I learned that the short-term satisfaction [of vaping] shouldn’t be more important than long-term health”.

3.2. Nontangible Results

Beyond the tangible products described above, YAC’s work led to increased understanding by YAC members and VapeRace researchers. VapeRace researchers gained a better understanding of youth views about vaping and were able to obtain feedback on plans for emerging work (e.g., cessation program development). YAC members increased their knowledge of the vaping epidemic and scientific research methodology (e.g., basic, clinical, epidemiological, community-based) as well as the impact they could have on their community. For example, YAC participants commented that “I learned a lot of new things from the [researchers]”, “I felt I was helping some of the VapeRace projects by giving my opinion”, “Each of us, in our own ways, has the potential to do great things. Youth vaping poses a threat to this potential, and thus, leaves our collective future compromised”, and “This experience has given me information and confidence to approach my friends to get them to stop using vapes”. Indeed, participating in YAC increased awareness and deepened understanding of how youth, especially when they combine efforts with their peers, have the power to effect social change. In particular, gaining an understanding of how tobacco company marketing and advertising targets youth and how this exposure influences vaping as well as of the negative health effects of vaping fueled YAC members’ interest in protecting peers. Several YAC members shared their viewpoints about peer vaping with quotes such as the following: “Now I know there is a reason [my peers] are vaping and I want to help them” and “I don’t want to see what happened with cigarettes happen with vaping. I don’t want others to ruin their futures because of addiction”. Specifically, they described intentions for future actions, such as having conversations with friends and encouraging their schools to adopt and enforce anti-vaping policies.

YAC participants also reported gaining comfort in interacting with professors and researchers. Furthermore, they reported an increased interest in becoming involved in undergraduate research and pursuing research careers. Involvement with YAC also served as a professional development opportunity for the undergraduate and graduate student research assistants. They honed skills in motivating youth, facilitating groups, mentoring youth, providing feedback and encouragement, and recognizing accomplishments.

4. Discussion

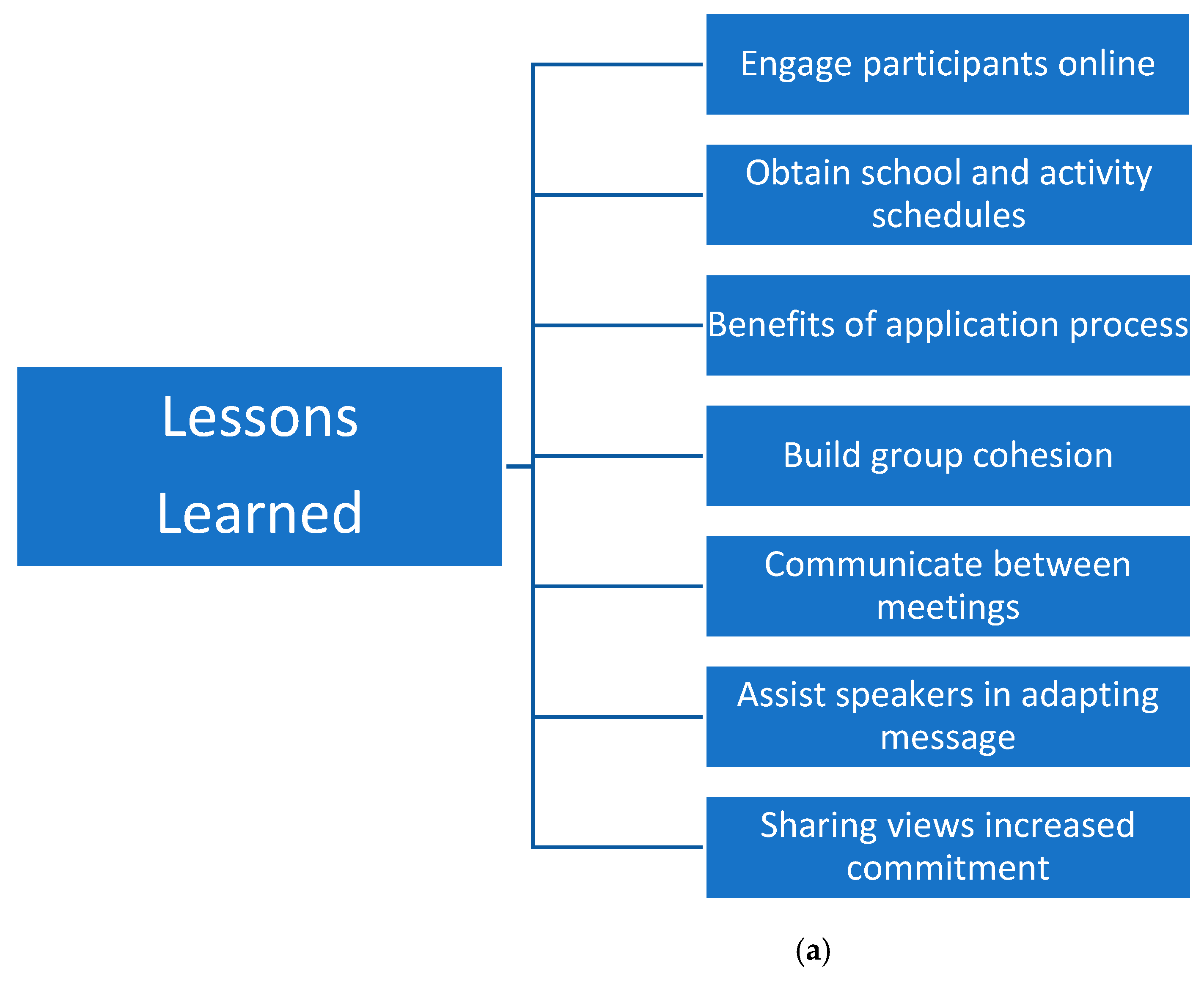

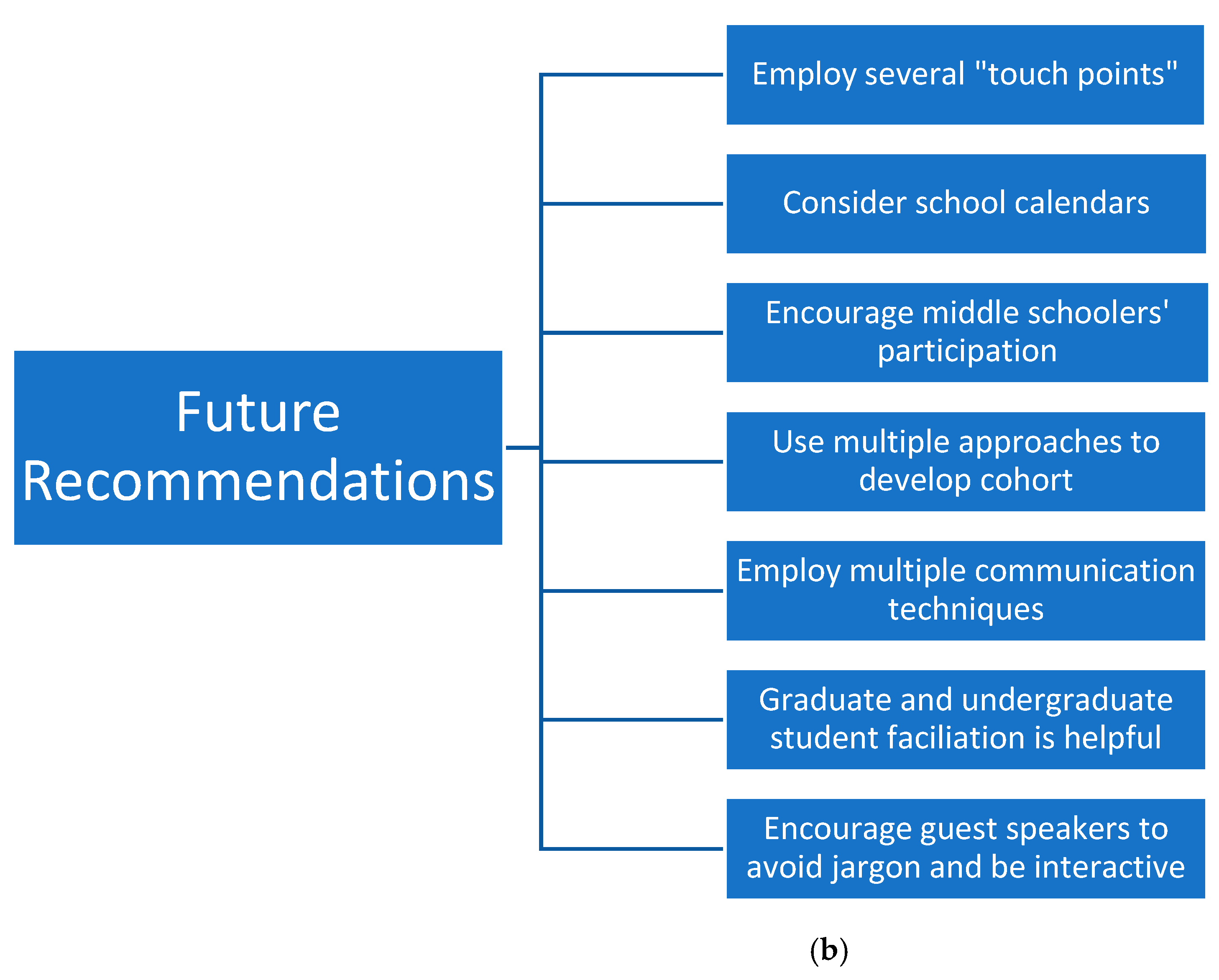

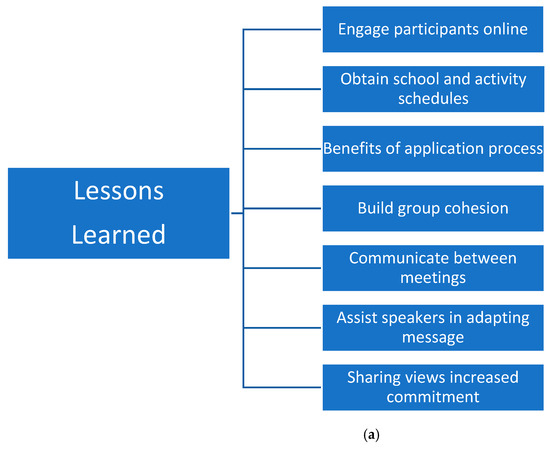

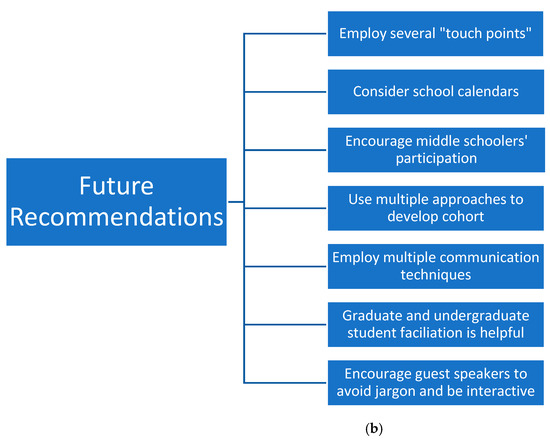

Based on these projects and the process of engaging youth in solutions to the youth vaping epidemic, we summarize lessons learned and offer recommendations for future undertakings that engage youth through youth advisory groups (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Summary of lessons learned. (b) Summary of future recommendations.

4.1. Logistical Issues

4.1.1. Meeting Online

The first cohort was formed with physical distancing and closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic still in place in some areas; therefore, meeting online was a necessity. Meeting online also allowed for participation from youth across geographic areas. However, despite increased comfort with online meeting technologies, their continued use may have decreased engagement for some, especially those who preferred face-to-face interaction. For YAC members with school and other commitments still taking place primarily online, additional online meetings could present engagement challenges (e.g., Zoom fatigue). Thus, we worked to engage YAC members using an array of techniques, such as small group work, trivia games, and frequent shifts between information delivery and activities.

4.1.2. Scheduling

Meeting online allowed for greater geographic representation, but working across multiple time zones presented challenges in selecting meeting times. Even with YAC participants in the same time zone, students ended their school days at differing times, had different school calendars (e.g., beginning and ending of academic year, days off school, exam periods), and many participants were involved in other after-school activities. Thus, it is helpful to gain information about the specifics of their school calendars and other obligations during the application process to facilitate finding an optimal meeting time. One possibility to address some of these challenges would be to secure school buy-in and permission for students to participate in meetings during the regular school day.

4.1.3. Participants

We strategically chose to use an application rather than merely a sign-up process for youth to participate in YAC. This approach provided students the opportunity to gauge their interest ahead of time, weigh the time commitment, and assess their willingness to engage in work to prevent youth vaping. Thus, our hope was that employing a selection process would lend greater authority and meaning to participating and would result in only students who would be truly committed and engaged in the work applying to participate. In reality, because all students who applied had excellent applications, they were accepted; however, having been chosen through a selection process seemed to be meaningful to these teens, indicating it did shape their commitment and participation levels. Further, YAC meeting attendance rates and the quality of outcomes produced suggest this strategy was successful. Future projects may want to consider including recommendations from teachers, community leaders, or other similar adults to accompany the youth applications. Such recommendations could provide insights into students’ interests and skills that would be helpful in creating a well-rounded group, particularly in pools with a large number of applications.

An additional consideration is participant age. Although students from 8th–12th grade participated in both YAC cohorts, just over half (53.8%) of the participants were in 11th or 12th grade. However, students, on average, initiate e-cigarette use during middle school (age 14.5 years) [24], and 3.3% of middle school students currently use e-cigarettes [25]. Moreover, current recommendations suggest beginning to provide tobacco prevention information by at least age 11 or 12 [26]. Therefore, involving more middle schoolers or focusing exclusively on middle schoolers should be considered for future YAC cohorts and other anti-vaping efforts.

4.2. Building Group Cohesion

Developing strong group cohesion from the start is vital to a successful youth advisory board. From the first moments, we sought to help youth connect, get to know each other, and feel part of the team. Toward these goals, we were quick to greet students as they joined Zoom, learned participant names, displayed our pronouns and invited students to do the same, engaged in chitchat with those who joined ahead of the meeting start time, invited questions and comments at any time, and encouraged participants to keep their cameras on throughout the meetings. We also found that having a relatively large team of faculty leaders and research assistants was helpful in maintaining engagement. Our team was able to monitor engagement during meetings and employ techniques to recapture attention when it began to wane or re-engage participants who might become distracted. For example, research assistants could post information, comments, or questions in the Zoom chat, text the meeting moderator to suggest a format shift, or interject questions or comments to spur or redirect discussion in the Zoom session.

Working in small groups also facilitated group cohesion. When working with a smaller set of people, the youth had more time to get to know each other, bond, craft project ideas, and achieve their goals. These small groups also allowed for more direct coaching and mentoring by the facilitators both during YAC meetings and via GroupMe between meetings, which was beneficial to both the YAC members and facilitators. The small groups enjoyed working with and learning from each other, and several groups elected to hold meetings in addition to the monthly ones to advance projects.

4.3. Communication

Because we met as a full group monthly, we found it helpful to have other communication channels to provide opportunities for more frequent interaction. We found the GroupMe app to be a particularly effective communication tool because it operates like text messaging, which is a preferred mode of communication for this age group. Further, each small group had their own GroupMe chat with one of their small group facilitators designated as the primary contact. Facilitators used GroupMe to send out meeting reminders and recaps of monthly meetings, reminders and encouragement about group projects, and breaking news related to vaping. We believe that having key contacts that were closer in age to the youth than the faculty researchers made communication more comfortable and simultaneously cultivated interest in attending college, getting in involved in undergraduate research, and potential research careers.

4.4. Opportunities for Meaningful Collaboration

Sharing their viewpoints, offering their insights and opinions, and having their voices heard—whether with their small groups, the full YAC cohort, or VapeRace Center researchers—reinforced the value of YAC members’ contributions and made the work worthwhile. This sense of meaning further increased engagement and motivation for the work. However, while YAC members benefitted from engagement with researchers and topic experts, we found that not all meeting guests were able to successfully adapt their material and presentation style to a youth audience. We discovered during the first YAC cohort that, while researchers regularly present to colleagues and the larger scientific and academic community, they typically have much less experience presenting to lay audiences, especially youth ones. Thus, for the second YAC cohort, we provided tips and coaching for meeting guests to assist in their preparations. These suggestions included identifying key issues, keeping presentations brief and interactive, and using accessible, jargon-free language.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

Our work with the VapeRace YAC had several strengths. The experience engaged youth in research focused on youth. This focus provided youth opportunities to share their insights and opinions with researchers; thus, rather than simply providing data for analysis in studies, they were contributing their lived experiences (i.e., insights from interacting with peers across a variety of contexts). This approach involved reciprocal relationships between youth and researchers and multidirectional communication (i.e., youth sharing their views and knowledge with researchers and researchers sharing their views and knowledge with youth). Another strength is that this project addressed calls to involve youth in tackling the youth vaping epidemic specifically. Youth advisory councils have been infrequently involved in vaping prevention efforts, and future teams considering youth advisory councils will benefit from the approach and lessons learned in this project. Additionally, our use of online meetings and group development activities was able to transcend geographical boundaries. Especially given increased technological options, access, and comfort, health researchers and advocates may wish to employ online structures for such councils. Beyond the regular full group meetings, subgroups also connected via technological interfaces, such as GroupMe, which facilitated additional development and sharing of information. These techniques also were strengths of the project, as was our overall frequency of contact with the youth members. Certainly, the interest and commitment of the YAC participants was a highlight of the work. The dedication of these youth to addressing the youth vaping epidemic buoyed our hopes for a healthier future.

Alongside these strengths, the limitations of the project also should be considered. First, our focus was on youth vaping; thus, the outcomes of the work may not apply as well to projects with other age groups or involving use of other substances or different risky behavior. Second, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic may have influenced youth participation, especially during the initial cohort year when some activities were still remote. Although the effects are not fully understood, organizers of future online youth advisory councils may wish to consider potential pandemic-related effects in planning for and implementation of their groups. Third, despite broad recruitment initiatives, each of the YAC cohorts would have benefitted from increased diversity (e.g., racial and ethnic, geographical, sexual and gender identity), and increased representation in future work may provide helpful information to improve similar endeavors that engage youth. Fourth, in a related vein, increased participation from middle school students may have been helpful, especially given when exposure to vaping typically is prevalent. Finally, despite its benefits, online participation also has associated limitations (e.g., types of projects possible, preferences of some youth, influences on relational development). Although the project has limitations, we believe that the YAC enhanced VapeRace researcher understanding and the overall work, developed youth participants’ understanding of research and awareness of the health dangers of youth vaping, and provides a useful framework for subsequent engagement of youth advisory councils in health-related research.

5. Conclusions

Harnessing the creativity and drive of youth is vital in health and well-being projects. Building on their knowledge and engaging in hands-on projects allowed YAC members to set the course for social change. Once they grasped the extent of the youth vaping problem, YAC members were anxious to work toward solutions and were buoyed by knowing that their work was important. One YAC member conveyed the idea this way: “I want to help my generation and future generations live a good life without the worry of the health side effects from vaping”. Participation in YAC resulted in these youth being well positioned to combat peer vaping. The resulting work of YAC members has been impressive, and we feel fortunate to have worked with these talented individuals. For us, this project underscores the vital importance of involving youth in vaping prevention and cessation efforts as well as in other initiatives related to youth health and well-being. As researchers, we also appreciated the opportunity to collaborate with the next generation of changemakers, policymakers, scientists, and community leaders. Ultimately, we learned as much from the YAC members as they learned from us and the larger VapeRace team.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/future3020008/s1, Figure S1: YAC Meeting Flow Model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.M., K.L.W. and J.L.H.; methodology, A.C.M., K.L.W. and J.L.H.; formal analysis, all authors; investigation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.M., K.L.W., L.A.W., O.A., K.V., S.K., M.M.T. and J.L.H.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, A.C.M., K.L.W., O.A. and J.L.H.; supervision, A.C.M., K.L.W. and J.L.H.; project administration, A.C.M., K.L.W. and J.L.H.; funding acquisition, K.L.W. and J.L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported, in part, by the American Heart Association under Award Number 20YVNR35500014. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Heart Association or the authors’ institutions.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Louisville (protocol code 21.0372).

Informed Consent Statement

Parental consent and youth assent were obtained for all YAC participants.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the VapeRace YAC members for their insights on and contributions to ending the youth vaping epidemic. We also thank Eowyn E. H. Garfinkle Plymesser and Julianna Clark for their assistance in leading the YAC groups.

Conflicts of Interest

Although Lindsey A. Wood is currently employed by a scientific consulting firm, Valeo Sciences LLC, which provides scientific advice to the government, corporations, law firms, and various scientific/professional organizations, including electronic delivery system and e-liquid manufacturers, she was a graduate student at the University of Louisville when participating in the VapeRace YAC work. Neither Valeo Sciences nor any of the organizations for which she has consulted had a role in the design and implementation of the VapeRace YAC or in preparation of this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General’s Advisory on E-Cigarette Use Among Youth; Office of Surgeon General: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/surgeon-generals-advisory-on-e-cigarette-use-among-youth-2018.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Birdsey, J.; Cornelius, M.; Jamal, A.; Park-Lee, E.; Cooper, M.R.; Wang, J.; Sawdey, M.D.; Cullen, K.A.; Neff, L. Tobacco Product Use Among U.S. Middle and High School Students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park-Lee, E.; Jamal, A.; Cowan, H.; Sawdey, M.D.; Cooper, M.R.; Birdsey, J.; West, A.; Cullen, K.A. Notes from the field: E-Cigarette and nicotine pouch use among middle and high school students—United States, 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.A.; Villanti, A.C.; Quisenberry, A.J.; Stanton, C.A.; Doogan, N.J.; Redner, R.; Gaalema, D.E.; Kurti, A.N.; Nighbor, T.; Roberts, M.E.; et al. Tobacco product harm perceptions and new use. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20181505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; McCausland, K.; Jancey, J. Adolescent′s health perceptions of e-cigarettes: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bold, K.W.; Krishnan-Sarin, S.; Stoney, C.M. E-cigarette use as a potential cardiovascular disease risk behavior. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotts, J.E.; Jordt, S.E.; McConnell, R.; Tarran, R. What are the respiratory effects of e-cigarettes? BMJ 2019, 366, l5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, R.; Bhatnagar, A. Cardiorespiratory and immunologic effects of electronic cigarettes. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2021, 8, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layden, J.E.; Ghinai, I.; Pray, I.; Kimball, A.; Layer, M.; Tenforde, M.W.; Navon, L.; Hoots, B.; Salvatore, P.P.; Elderbrook, M.; et al. Pulmonary illness related to e-cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin-Final report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 382, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, C.; Simovic, T.; Heefner, A.; Colon, M.; Tunon, E.; Cobb, K.; Thode, C.; Breland, A.; Cobb, C.O.; Nana-Sinkam, P.; et al. Evidence of premature vascular dysfunction in young adults who regularly use e-cigarettes and the impact of usage length. Angiogenesis 2024, 27, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeek, D.L.; Kass, A.P.; Chiel, L.E.; Boyer, E.W.; Casey, A.M.H. A review of toxic effects of electronic cigarettes/vaping in adolescents and young adults. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2020, 50, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Agency for International Development. Youth councils: An Effective Way to Promote Youth Participation. USAID Educational Quality Improvement Program 3. 2009. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/youth-councils-an-effective-way-to-promote-youth-participation/42043594 (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Morena, M.A.; Jolliff, A.; Kerr, B. Youth advisory boards: Perspectives and processes. J. Adolesc. Health. 2021, 69, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.; Gupta, S.; Obare, R.; Brindlmayer, M.; Gayles, J.; Jessee, C.; Sladen, S. Youth Advisory Councils: Eight Steps to Consider Before you Engage; United States Agency for International Development (USAID): Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adolescent Health Initiative. Creating and Sustaining a Thriving Youth Advisory Council; University of Michigan Health System: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2014. Available online: https://health.mo.gov/living/families/adolescenthealth/pdf/creating-and-sustaining-a-thriving-yac.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Geffen, S.R.; Wang, T.; Cahill, S.; Fontenot, H.B.; Conron, K.; Mosquera Wilson, J.; Avripas, S.A.; Michaels, S.; Johns, M.M.; Dunville, R. Recruiting, facilitating, and retaining a youth advisory board to inform an HIV prevention project with sexual and gender minority youth. LGBT Health 2023, 10, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana, M.; Valdez-Soto, M.; Brockman, T.A.; Balls-Berry, J.E.; Guadalupe Zavala Rocha, M.; Allyse, M.A.; Dsouza, K.N.; Riggan, K.A.; Juhn, Y.; Patten, C. Creating a pediatric advisory board for engaging youth in pediatric health research: A case study. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 5, e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, O.; Rosenberger, C.A.; Poku, V.O. Implementing a youth advisory board to inform adolescent health and medication safety research. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, K.N.; Orellana, M.; Riggan, K.A.; Valdez-Soto, M.; Brockman, T.A.; Rocha, M.G.Z.; Balls-Berry, J.E.; Juhn, Y.; Patten, C.A.; Allyse, M.A. Views and experiences of youth participants in a pediatric advisory board for human subjects research. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 5, e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, K.J.; Edwards, A.L.; Paulson, A.C.; Libby, E.P.; Harrell, P.T.; Mondejar, K.A. Rethink Vape: Development and evaluation of a risk communication campaign to prevent youth e-cigarette use. Addict. Behav. 2021, 113, 106664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Empowerment Through Photo Novella: Portraits of Participation. Health Educ. Q 1994, 21, 171–186. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/45049549 (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharapova, S.; Reyes-Guzman, C.; Singh, T.; Phillips, E.; Marynak, K.L.; Agaku, I. Age of tobacco use initiation and association with current use and nicotine dependence among US middle and high school students, 2014–2016. Tob. Control 2020, 29, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.; Park-Lee, E.; Ren, C.; Cornelius, M.; Jamal, A.; Cullen, K.A. Notes from the Field: E-cigarette use among middle and high school students-United States, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022, 71, 1283–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, B.P.; Walley, S.C.; Boykan, R.; Caldwell, A.L.; Camenga, D. Protecting children and adolescents from tobacco and nicotine. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2023061806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).