Abstract

The migration experience of unaccompanied foreign minors (UFMs) has significant emotional and cognitive implications. The present research explores the way in which migration trauma influences the cognitive and emotional development of UFMs, contextualizing the current situation of this population in relation to migration trauma and neuroeducation. This study aimed to understand these impacts by examining the lived experiences of UFMs. An interpretative paradigm was adopted alongside a qualitative methodological approach, employing a collective case study technique to explore individual narratives in depth. The present findings highlight links between migratory trauma and cognitive and emotional development through a neuroeducational lens. Emphasis was placed on the importance of understanding the unique experience of each child and the critical role of professional support in mitigating the adverse effects of migration trauma.

1. Introduction

Immigration has significantly increased in recent years [1]. This is true in the case of UFMs (unaccompanied foreign minors), with the number of such arrivals also increasing; however, it is important to note that this specific type of migratory experience cannot be understood in the same way as others, as the younger age of those typically involved requires special attention be given to both their context and the stage in their life course at which they find themselves [2].

Migratory contexts often involve very complex situations. The main countries of origin for UFMs are Senegal (4%), Guinea (5%), Algeria (7%), Mali (8%), and Morocco (56%). UFMs are frequently fleeing war conflicts, group or intra-family violence, or extreme poverty, which are inherent to these places. Additionally, these young individuals face violence and abuse by traffickers during their journeys [3,4]. Alongside these challenges, additional hurdles, including long wait times, uncertainty about the future, and anxiety felt upon arrival, must also be considered [5]. This is further complicated by the physical and geographical distance separating UFMs from their parents, as well as the availability of support networks in the host country, which hinders their transition to adult life and relocation [6].

This critical moment in their lives coincides with a sensitive educational stage in terms of cognitive and emotional development. Lived experiences and the immediate surrounding environment are particularly vital at this stage [7], as the sensory environment plays a decisive role in determining the way in which individuals grow, learn, and develop socially [8].

When discussing neuroeducation in relation to UFMs, it is essential to recognize that the migration experience has severe emotional and cognitive consequences for these minors. This reality presents numerous challenges for this population that remain underexplored in the current research [9].

It is evident that there is a need to explore the challenges and difficulties faced by unaccompanied foreign minors (UFMs) during their migration process. Thus, the aim of the present qualitative research study was to explore the neuroeducational impact of migration trauma on cognitive and emotional development in UFMs.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Unaccompanied Foreign Minors: Definition and Characteristics

The term unaccompanied foreign minors (UFMs) refers to individuals aged under 18 years who are nationals of a non-EU member state or are stateless, and who, for whatever reason, access foreign territory without the legal assistance and representation of their parents or other legal guardian [10]. Their migratory flow is similar to that of adults, with relevant changes since 2013 [11]. In 2018, this type of migration started to rise abruptly, with 7026 arrivals being registered [12]. This led the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child to alert Spain and deliver a call for action for it to prioritize adequate care provision for unaccompanied migrant children [13]. Following this, an alarming number of 13,012 unaccompanied children was registered, implying a 103% increase over the previous year [14]. At the end of 2020, approximately 9030 minors were registered. This drop was due to the fact that, during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, humanitarian aid was prioritized over the registration of minors [15]. It should be noted that the exact number of the total UFM population is difficult to determine due to a lack of coordination on the part of regional authorities and a lack of rigor in the calculation of statistics [9].

According to the Ministry of the Interior [16], the main countries of origin of minors arriving to Spain are Senegal (4%), Guinea (5%), Algeria (7%), Mali (8%), and Morocco (56%). This has led to the diversification of trans-Saharan routes in an attempt to avoid maritime border control. However, prior to Moroccan minors becoming the primary group in the UFM migratory flow to Spain, “sub-Saharan” minors already accounted for a large part of migration patterns predating the colonial era, due to significant population mobility across the Sahara. Following colonialism, new borders were defined and the African continent was divided, leading to the disruption of the trans-Saharan migratory flow [3]. Most UFMs either lack personal identification documents or only have unreliable or dubious documentation [17]. In addition, the migratory context from which they come is often very complex. Indeed, such minors typically come from especially large families with few economic resources, and at the same time, they are often fleeing war conflicts, intra-family violence, forced marriages, poverty, etc. [13]. This causes survival costs, abuse and aggression, and stress and breakdowns [3]. The young age of these minors, ranging from 10 to 16 years old, exacerbates the fact that they often have problems communicating in the language of the host country. Added to this, in their new host country, they must take on new challenges related to being in the care and foster system [13], such as protracted wait times, uncertainty about the future, and anxiety [5,14].

2.2. Conditions of Children and Adolescents in the Migration Process

In order to understand the challenges and difficulties that children and adolescents face during the migration process, it is essential to begin by describing the realities they encounter before starting their migration journey.

There are multiple factors that influence the decision to migrate. On the one hand, personal factors emerge, such as the search for a life project that their country of origin does not allow them to achieve; on the other hand, family circumstances related to abuse or lifestyle also prevail. Finally, socio-economic aspects can also drive these young people to emigrate in search of work as a means of financially supporting their families [9].

UFMs typically arrive to Spain in an irregular manner through various means of entry, although boats are most commonly used, often endangering their health and lives. Regardless of the means of entry, the process is the same once they cross the border, with them being located by emergency services and/or authorities who identify them as minors and verify their age [13,18,19,20].

The determination of their age has crucial consequences for their protection in the destination country. In Spain, if a minor is recognized as such under Law 01/1996 [21], they automatically receive protection under the Convention on the Rights of the Child and regulations for the protection of minors. On the other hand, if they are wrongly categorized as an adult, they fall under the jurisdiction of Law 04/2000 [22], which may result in their expulsion and deprotection, with them being treated as a “dangerous child”. This erroneous categorization can lead to the denial of fundamental rights, such as access to housing, education, and family reunification, as their migration is incorrectly deemed to be for economic reasons and not for the protection of their basic rights or survival. When a child is properly recognized and registered, the administration must then decide whether to repatriate or sanction their stay, but, in many cases, repatriation can result in abuse, both by the authorities and by the child’s own family [23].

When repatriation is not possible, a guardianship and residency process is carried out. Both processes are often accompanied by delays related to guardianship processing delays, overcrowded centers, and a lack of identity documentation or registration cards. In addition, children and adolescents are often completely uninformed about their status [24].

From here on, the care model applied, for the most part, is based on residential care (centers, residences, and flats), as few children are taken in by foster care programs. Residential care aims to guarantee the child a safe environment that ensures their development and allows them to create emotional bonds with other children who have suffered similar experiences. However, according to a UNICEF report published in 2019, the foster care system is not well adapted to the reality of children and adolescents [24,25].

One of the main challenges faced by unaccompanied foreign minors (UFMs) is the eventual loss of their status as minors, which excludes them from protections afforded under the Protection of Aliens Regime in Spain. Currently, there are only two types of guardianship, namely family guardianship and supervised flats. This is insufficient in terms of accompanying UFMs as they transition into adult life. This generates feelings of helplessness and uncertainty, exacerbated by the lack of state support in terms of accommodation and means of subsistence. Although UFMs obtain a temporary residence permit, renewal requires a work contract, which is often difficult to obtain, as the available jobs are precarious and poorly paid. As a result, these young people face the risk of social and labor exclusion, increasing the possibility of them becoming involved in criminal activities due to their vulnerable situation [9,26,27].

2.3. Neuroeducational Consequences of the Migratory Journey in UFMs

Children’s brains are constantly being formed and shaped, starting in the womb. This period is of vital importance, as, without proper control, interference with physiological processes can occur and lead to congenital malformations. Prenatal care is, therefore, of paramount importance. However, in developing countries (usually the countries of origin of UFMs), prenatal care is often insufficient due to factors such as the saturation of the public health system or a deficiency in equipment, personnel, and medication in hospitals [28].

Following childbirth, the brain is particularly sensitive to factors such as nutrition, stress, and lack of affection. These can interfere with normal brain development and cause long-term learning and memory dysfunction by affecting the proper development of the hippocampus and amygdala. Alongside this, the influence of the environment must also be considered in light of various environmental factors, such as biological factors (e.g., malnutrition and infections) and psychological factors (e.g., child abuse and domestic violence). Research conducted in African countries revealed that these aforementioned factors significantly impact learning processes due to childhood experiences related with abuse, school dropout, or hunger [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Alongside this, the high number of cases of neglect or oppression found in UFMs’ countries of origin must be considered. Emotional neglect leads to a reduction in the volume of cortical white matter, with neglected children exhibiting slower development compared to children from emotionally supportive families. Furthermore, mistreatment during childhood can cause long-lasting dysfunctions in key neuroregulatory systems and alterations in the development of fundamental brain structures, resulting in deficits in cognitive functioning and difficulties in affective and behavioral self-regulation [8,29,30].

Once adolescence arrives, the cultural setting and cultural values begin to play a crucial role in the formation of the adolescent’s identity. In addition to the problems of childhood, new issues emerge, such as high drug or alcohol consumption and incessant fighting in slums. In these highly threatening environments, the continuous secretion of hormones, such as cortisol, affects brain development. The structural organization of the prefrontal cortex, which is related to the development of self-control functions, is one of the most affected areas [3,31].

The migration of children and adolescents usually takes place during the adolescent stage, which is characterized by different biopsychosocial changes and sensitivity to sources of stress. For this reason, this transitional stage is affected both by age-related factors, such as the creation of identity, and factors intrinsic to the migration process, such as separation from the family group or the gaining of autonomy and independence [32].

The migration journey and the border crossing itself are characterized by emotions such as fear and uncertainty. The aforementioned adolescent factors combine with high levels of stress and mixed emotions about not returning. At the border, these feelings are heightened by the difficulty of access and fears of rejection or detention. This migration affects children’s defense mechanisms, causing damage to the psyche related to depressive, manic, neurotic, and adaptive factors. Furthermore, traumatic events suffered during the journey may cause the child to experience post-traumatic stress and depression, which will subsequently influence their acculturation process [33,34,35].

Once in Spanish territory, hope turns into despair and frustration. Detention and age determination processes are accompanied by emotional reactions that oscillate between depressive reactions, such as mourning and homesickness, and persecutory reactions, which are related to fear of the unknown. Furthermore, misinformation about these procedures produces emotions of uncertainty and distress in children, which affects their mental and emotional health [24,33,36].

A child’s stay at a reception center also has a socio-cognitive influence on their development. Centers are often overcrowded and the conditions under which UFMs sleep, wash, and live together have a significant impact on their mental health, which can lead to suicide attempts or addictions. This situation is also exacerbated by insufficient self-regulatory competence and the questioning of authority figures, often leading to possible impulsive and aggressive behavior, behavioral problems, and rule breaking [24].

Likewise, the need to integrate into a new country in a forced and rapid manner leads to both psychological and emotional problems that often result in situations of exclusion by the host society, leading to an increase in already existing affective deficiencies and the emergence of or increase in disruptive behaviors [14].

Once these young people come of age, they must then integrate into wider society without any support provision. Especially given the fact they are already coming from a hugely disadvantaged situation, this often leads to emotional and psychological problems that can lead to disruptive behavior and affective deprivation. In addition, their identity, values, beliefs and attitudes are chipped away as a new pseudo-identity develops due to culture shock. This abrupt process of integration into a new culture is related to illnesses such as depression and anxiety. Furthermore, acculturative stress has been shown to be related to factors such as discrimination [9,32,33,37].

Finally, it is noted that these young people leave the system without sufficient preparation to cover their needs, both materially and psychologically, resulting in significant deficiencies in relation to their psychosocial and emotional wellbeing [9].

3. Materials and Methods

The present study was framed within the interpretative paradigm, following an eminently qualitative methodological approach using the collective case study technique, i.e., a rigorous and in-depth interpretative study of a system or unit of analysis, within which the relevance, impact, and effectiveness of contextual particularization supersedes the validity of naturalistic generalizations [38].

In-depth interviews were conducted with 11 professionals working directly with unaccompanied foreign minors (UFMs) in a variety of contexts, including shelters, non-governmental organizations, social services, and specialized educational programs.

3.1. Participants

The participants were selected through purposive convenience sampling. For this purpose, a description of personal characteristics was previously requested. Specifically, to be eligible, participants were required to have a basic knowledge of neuro-pedagogy and be actively immersed in the field of work of the study context. The academic, professional, and cultural profiles of the participating informants varied according to their background and field of study. In order to safeguard the privacy of informants and ensure the study’s commitment to confidentiality, personal identifiers were removed and individual participants are referred to through the use of coding [Table 1].

Table 1.

Coding of informants—own elaboration.

3.2. Procedure

Interviews were analyzed using the MAXQDA 2022. This process involved interview translation and transcription, followed by the subsequent generation of preliminary codes to describe the data. The codes were extracted by analyzing the responses to the questions posed during the semi-structured interviews.

The participation of the interviewees was strictly voluntary. The interviews were conducted face-to-face or online, depending on the informant needs. The interviews lasted approximately two hours each. Prior to conducting the interviews, the researchers generated a rapport with the informants in order to instill a safe and trusting environment. All the interviews were recorded with permission and transcribed verbatim for a content analysis. Prior to the analysis, the corresponding interview transcript was reviewed with each interviewee in order to ensure its veracity.

Data collection for this study commenced in April 2024 and concluded in July 2024, spanning a total of four months. Over these months, a structured approach was maintained to ensure consistent and reliable data collection.

3.3. Instrument

In the present research study, semi-structured interviews were conducted. The interviews were run ad hoc and based, on the one hand, on an exhaustive review of the existing literature on the subject and, on the other hand, on experiences shared by the professionals who validated the interview guide.

The interviews allowed pragmatic information to be gathered about professional perceptions of the neuroeducational reality lived by the UFM population.

Content validity was determined after administering the instrument to a pilot sample with similar characteristics. In order to ensure the scientific rigor of the study, compliance with the criteria of adequacy, relevance, and congruence was rigorously evaluated using an expert panel. Expert validation was conducted by reporting the agreement along a three-point Likert scale (1 = inadequate, 2 = adequate, 3 = highly adequate). Items were only considered for inclusion if they obtained a mean score greater than 2.7. The inter-rater agreement following this process was K = 2.93.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The analysis entailed a thorough examination of the frequency and co-occurrence of redundant and nested codes, using advanced coding tools in the MAXQDA 2022 in order to ensure rigorous and systematic data processing.

3.4. Data Analysis

For data reduction and information organization purposes, a deductive system of categories was established. Categories were defined that met the requirements of the study [Table 2]. The categories were validated through expert panel consultation and triangulation. In order to assess the reliability according to the degree of agreement between expert judges, Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated, revealing moderate agreement (κ = 0.45).

Table 2.

Category system for analyzing interview protocols.

4. Results

In order to address the neuroeducational factors impacting UFMs during their migration process, it is essential to begin by describing the realities they encounter prior to initiating their migration journey. The first variable considered when analyzing the developmental process of these children pertained to their development during the gestational stage, as an infant’s brain is constantly being formed and molded in the womb during this period. This stage is of vital importance, since, without proper control, a disturbance in physiological processes can occur and lead to congenital malformations. According to those interviewed, health control during pregnancy is insufficient, as is the coverage of the mother’s basic needs, due to culture, poverty, and the lack of public health care. Financial hardship was highlighted as the main factor.

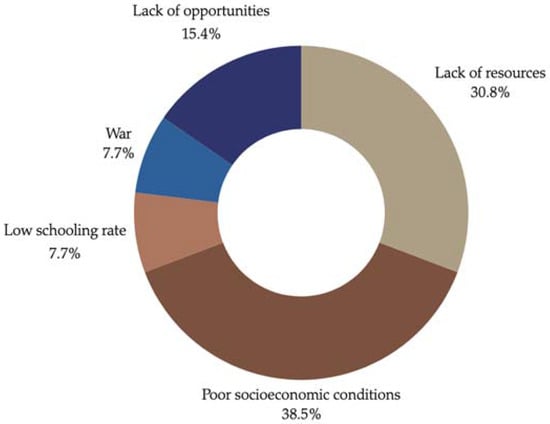

The interviewees also agreed that a lack of resources (30.8%) and poor socioeconomic conditions (38.5%) pertaining to their country of origin are the main factors that affect conditions when migrant minors arrive to their destination country. However, other characteristics such as a lack of opportunities (15.4%), a low schooling rate (7.7%), and war (7.7%) were also mentioned in the interviews [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

General conditions inherent to countries of origin.

It should be noted that this analysis provides an overview of migration conditions. However, multiple testimonies highlight the fact that the context inherent to the country of origin is multi-factorial, and so any given reality is subject to different political, economic, social, and cultural factors, even when talking about minors coming from the same country.

“It depends a lot, a child coming from the southern part of Morocco has nothing to do with a child coming from the northern part, for example, I have had children from the south who came from very wealthy families, with a lot of money and, on the other hand, children coming from the north who have had a much harder life and have been much poorer. And then, if you compare with other African countries, that are much more different, especially at a cultural level and at the level of the education they have received, and at the level of resources, a boy coming from Gambia will have had far fewer opportunities than a boy coming from Morocco”.[A9]

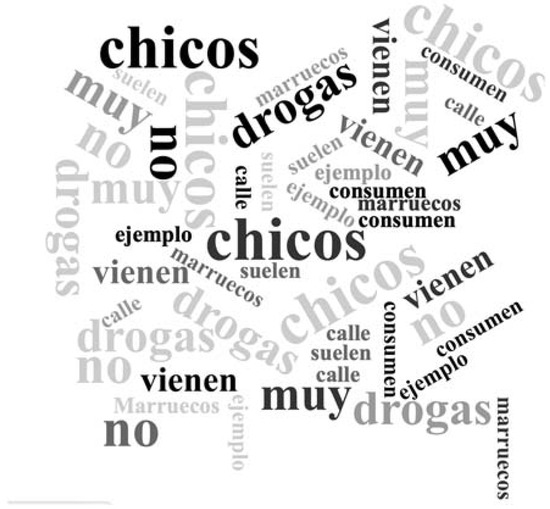

However, it is true that most informants report that the minors under study come from lives marked by abuse, drug and alcohol abuse, school dropout, unemployment, and fighting. The words most frequently repeated by interviewees when asked about the type of environment from which these minors come were “violence”, “boys”, “street”, “drugs”, and “consumption”, amongst others [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Word cloud detailing UFM backgrounds.

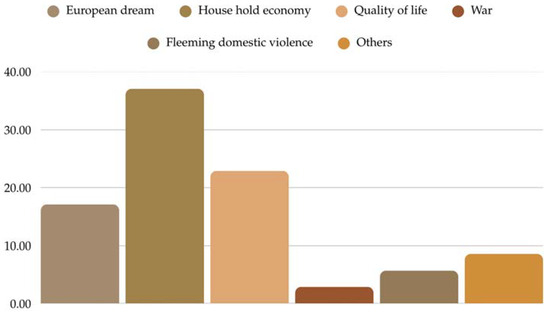

In addition, multiple factors emerged that influence the decision to migrate. The most important factor in terms of the most commonly mentioned determinant appears to be to economically support one’s family (39.3%). This was followed by quality of life (24.3%) and the pursuit of the European dream (18.1%), which also emerged as main factors. Finally, a number of other factors were also mentioned, although to a lesser extent; namely war, illnesses that cannot be treated in home countries due to insufficient healthcare provision, family reunification, fleeing domestic violence, and, least of all, the possibility of studying [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Reasons for departure.

According to the interviewees, such environments have consequences for normal child development and cause long-lasting cognitive and emotional dysfunction.

“Yes, especially memory, for example, the fact that these kids have early regression, there is post-traumatic stress and the dissociation they suffer greatly affects the way they understand their own trauma, many times they forget, even, things that have happened because of post-traumatic stress”.[A5]

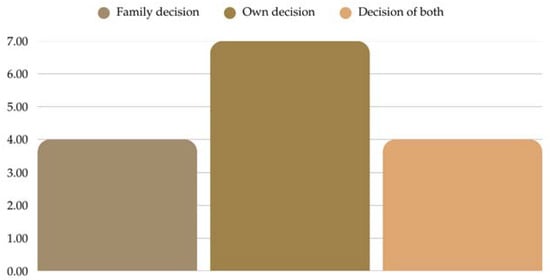

With regards to the decision to migrate, three alternatives emerged, with migration stemming from either the child making the decision to migrate alone, the family making the decision, or both agreeing that the child will migrate [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Decision to depart.

It is also important to note that it was often mentioned by interviewees that society encourages children from an early age to consider it necessary to flee their country in order to have a better future and take care of their family economically. This means that these children are pressurized, almost brainwashed, from a very early age.

“To be sent here, they must have one foot in childhood and one foot in adulthood”.[A6]

“If you start telling a child when they are very young that Spain is good, that they have to go to Spain, that the good life is in Spain, it is normal that when they are 15 years old they will say I am going to Spain, but it is not really their decision, it is rather something that has been instilled in them since they were a child”.[A9]

Arrival in the country of destination occurs irregularly. Different means of transportation may be used; however, the specific type of transport opted for usually endangers the traveler’s health and life. Along the journey itself, the risk of abuse and violence also exists, which has an impact on subsequent post-traumatic stress and will directly affect child development. This being said, regardless of the form of entry, the outcome is always the same, with the arriving minor being picked up by emergency services and/or local authorities who identify them and verify their age.

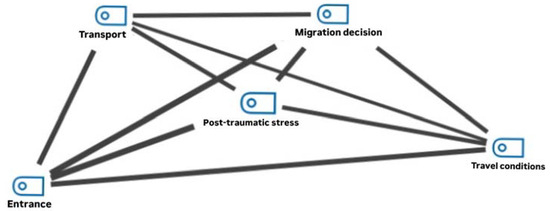

Figure 5 presents the relationship between factors pertaining to the migratory journey and post-traumatic stress. Given the subsequent effects of this stress on child development, it is clear that migration conditions, to a large extent, affect both cognitive and emotional aspects of the child.

Figure 5.

Correlation between post-traumatic stress and different factors of the migration journey.

The interviewees agreed that the time at which the minors’ age is determined represents one of the most impactful moments in terms of the possible later development of mental disorders in these minors, due to the fact that this event is characterized by emotions such as fear and uncertainty.

“He told me how they started bombarding him with questions during the age determination process. He had a dent in his head and they started asking him about the dent in his head, that he likely got as a kid fighting over a piece of stick, literally, in Morocco or Algeria, and, well, they just kept pushing him about the dent in his head until he couldn’t handle the stress or the situation anymore and he started hearing voices”.[A11]

“They usually come with stress and fear, since they usually come with a lot of fear about being caught as adults, because if they are deemed to be adults, their plans are totally ruined, and all the effort to get to Spain, comes to nothing, and I tell you, many are afraid and when the time comes for them to do the test they do not want to leave their rooms”.[A2]

With regards to the situation in reception centers, a number of different opinions emerged from the interview transcripts. Notably, the perceptions appear to differ according to the geographical and socioeconomic area in which the center is located. A summary table is presented below that exhibits some of the opinions given by the participants [Table 3].

Table 3.

State of centers.

Nonetheless, both the integration of children in a new country and the way in which they relate to their environment have a profound impact on their psychological and emotional wellbeing. These processes not only affect adaptation to their new life, but they can also aggravate the difficulties they face. In general, the interviewees stated the belief that integration cannot be achieved for several reasons, including the limited independence of the minors involved, cultural differences, the individual personalities of the minors, and the resistance of the host society.

“Here in Ceuta they don’t even have the opportunity, know that here they are under the guardianship of the city and, therefore, they cannot go out alone, literally, they are in a prison, they can only have outings accompanied by their monitors”.[A2]

“At an adaptive level it is complicated, because, at the end of the day, Spain is a racist country, in which there are many behaviors of this type that make it much more difficult for these boys to integrate, and, also, at a religious and cultural level there are many differences, for example, they do not take well to women giving them orders, so this cultural and religious shock makes integration much more complicated”.[A5]

“Null, they put zero effort into integrating”.[A9]

“There is a lot of stigmatization of this group both in Italy and Spain”.[A11]

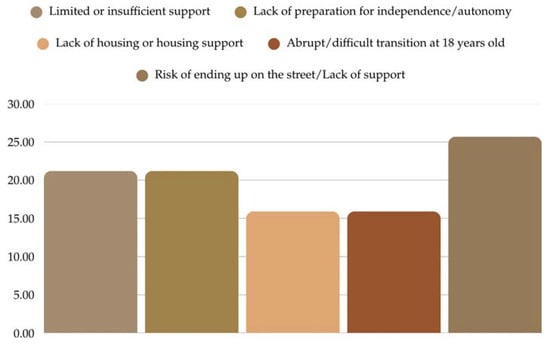

In relation to emancipation, it was noted that minors are neither accompanied through nor prepared for this process. In general terms, the present study revealed several challenges, which are presented in the following figure [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Primary challenges faced by minors during the emancipation process.

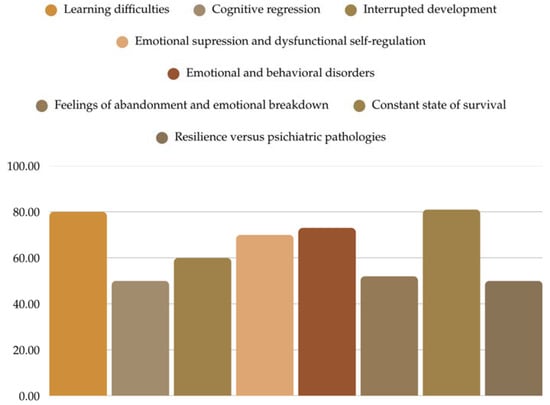

By means of a conclusion regarding the results produced by the present study, the following graph summarizes the main neuroeducational and emotional factors affected by migratory trauma in unaccompanied foreign minors (UFMs). This graph illustrates the prevalence of various cognitive, emotional, and behavioral difficulties reported in the interviews, highlighting the profound impact that the migratory process has on the development and wellbeing of these minors. The data emphasize the urgent need to implement specific support strategies to address the complex needs of UFMs and promote their resilience and adaptation to new realities [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Impact of migratory trauma on neuroeducational and emotional factors in unaccompanied foreign minors.

5. Discussion

The main aim of the present research was to analyze the neuroeducational factors that affect the migratory trauma experienced by unaccompanied foreign minors. The interviews conducted shed light on the existence of certain specific factors that directly bring about neuroeducational changes that subsequently affect the cognitive and emotional development of minors.

Some experts agree that inadequate prenatal monitoring can lead to a disturbance in physiological processes and congenital malformations, considering prenatal care and maternal healthcare provision to be major factors regarding fetal development. In agreement with that expressed by the informants in the present study, the authors consider that prenatal care in developing countries is often insufficient. This is due to factors such as the saturation of public services or the insufficiency of equipment, personnel, and medication in hospitals. Similarly, the authors of the present study also consider pre-existing beliefs and the social setting to play a role in determining the lack of medical provision. Interestingly, vulnerable situations such as unwanted pregnancies have also been suggested as determinants in existing literature, but were not mentioned in any of the interviews conducted here [28].

The minor’s background context emerged as the second main factor affecting their development. The informants agreed that the context inherent to the migrant’s origins is often highly complex. In this sense, aspects such as scarce economic resources, war conflicts, and domestic violence were mentioned in the testimonies. However, no information was found in reference to other common issues, such as forced marriage or poverty. This may be due to the fact that the professionals interviewed had mostly worked with male minors. With regards to threatening environments, drug use and violence emerged both in the interviews and in the literature review [3,13].

It should also be noted that the study informants concurred that children’s memories of their countries of origin were often mired in experiences of neglect or oppression. Emotional neglect diminishes the volume of cortical white matter in the brain and slows development relative to children from emotionally supportive family units. Furthermore, mistreatment during childhood can generate long-lasting disturbances in core neuroregulatory systems and alter the development of fundamental brain structures, resulting in defective cognitive functioning and impinged affective and behavioral self-regulation [8,29,30].

In accordance with that reported by previous research, migration factors related mainly with family economic support were revealed, and the collaborating study experts agreed with their importance. Similarly, the search for a life project or escape from abuse are also mentioned by the existing research. In contrast, health does not emerge as a factor in the existing literature [9].

In relation to arrival in the country of destination, many authors share the perspective uncovered in the present study that arrival is tinged by challenges faced throughout the journey and the risk of abuse or violence. Both the present informants and the existing literature also highlight aggressions perpetrated by the local population [3,39].

In this sense, previously conducted research argues that the threatening environments that UFMs are exposed to, both before and during migration, produce a continuous secretion of hormones, such as cortisol, that affect brain development. The structural organization of the prefrontal cortex is especially affected by this, with concomitant effects on the development of self-control functions [8,28].

In relation to the age determination process, previously published findings concur with the present outcomes that indicate influences on the child’s defense mechanisms, causing damage to the psyche related to depressive, manic, neurotic, and adaptive factors. Likewise, it was mentioned that traumatic events suffered over the course of the journey may cause a child to experience post-traumatic stress and depression, which will later influence the acculturation process [33,34,35].

With regards to the capacity of centers to meet these children’s needs, opinions have been raised in relevant literature that support the assertion that centers guarantee the minor a safe environment that supports their development and allows them to create emotional bonds with other minors with shared experiences [3]. In contrast, other authors have argued that these foster care systems are not suitably adapted to the reality lived by the children they are supposed to cater to [24].

Likewise, the existing literature agrees with the interviewees in the present study in that the need to integrate in a new country in a forced and rapid manner leads to both psychological and emotional issues that often converge in situations of exclusion by the host society. This creates a vicious cycle in which already existing affective deficiencies are further exacerbated, driving the emergence of new or heightened disruptive behaviors [14]. In line with this, it is clear that, once they reach adulthood, these young people must integrate into society from an already highly disadvantaged situation, without any support. This leads to emotional and psychological problems that can result in disruptive behaviors and emotional deficiencies [9].

Finally, it is important to highlight that no studies currently exist that specifically address the emotional and cognitive factors underlying unaccompanied foreign minors (UFMs). This research gap means that the unique psychological and developmental challenges faced by these individuals remain largely unexplored and misunderstood. Understanding these factors is crucial for developing effective support systems and interventions tailored to the specific needs of UFMs. Addressing this research void will be essential for informing policies and practices aimed at improving the wellbeing and integration of UFMs into society.

6. Conclusions

The present findings make it possible to confirm that the migration experience imposes severe and profound limitations on the emotional and cognitive development of UFMs, affecting their ability to adapt and thrive in their new environment.

From an emotional standpoint, it was revealed that many minors experience emotional suppression and dysfunctional self-regulation, which can lead to significant emotional and behavioral disorders. Additionally, they face feelings of abandonment and emotional breakdown, as they constantly strive and struggle for their mere survival. These factors not only affect their overall wellbeing, but they also impact their ability to form affective relationships and adequately adapt to their new context. Resilience in the face of psychiatric pathologies also shows wide individual variability, indicating different ways in which minors process and confront trauma and highlighting the need for personalized intervention approaches.

In terms of cognitive development, the present study identifies that many minors face learning difficulties, cognitive regression, and interrupted development. These difficulties are crucial for understanding the way in which migration trauma impacts minors’ ability to acquire and process new knowledge. This impact can have significant consequences for their academic performance and their capacity to adapt to a new educational and social setting.

As the global refugee crisis continues to escalate, the future of refugee minors, particularly in relation to migration trauma, demands urgent attention. The present findings suggest that, without immediate and long-term interventions, the compounding effects of trauma may hinder these children’s capacity to thrive in new environments. However, by understanding the nuanced ways in which trauma manifests across different developmental stages, it is possible to pave the way for more specialized support systems. Looking forward, it is crucial that collaborative frameworks be fostered across different educational, social, and psychological domains in order to equip refugee minors with the resilience and resources required for them to aspire to a bright future. The present study, therefore, underscores the need for a sustained commitment to addressing migration trauma, steering away from one-time interventions towards a more holistic and dynamic process that is aligned with the minors’ growth and integration stage. Finally, there is an urgent need to develop support approaches tailored towards the individual experiences of minors. The implementation of strategies based on the neuroeducational perspective is essential for addressing the complex emotional and cognitive difficulties identified in the present study. By understanding and applying these factors, more effective interventions can be designed that not only enhance the wellbeing of UFMs, but also facilitate their successful integration into society, promoting healthy and sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.-C. and J.E.-L.; methodology, E.O.-M.; software, S.A.-C.; validation, J.E.-L., S.A.-C. and E.O.-M.; formal analysis, S.A-C.; investigation, S.A.-C.; resources, J.E.-L. and E.O.-M.; data curation, S.A.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.-C.; writing—review and editing, J.E.-L. and E.O.-M.; visualization, S.A.-C.; supervision, J.E.-L. and E.O.-M.; project administration, J.E.-L. and E.O.-M.; funding acquisition, J.E.-L. and E.O.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by proyecto I+D+i PID2020-119194RB-I00 (TYNDALL/UFM). MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/. https://ror.org/003x0zc53 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Granada under registration number 1858/CEIH/2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alamá-Sabater, L.; Alguacil, M.; Bernat-Martí, J.S. New patterns in the vocational choice of immigrants in Spain. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1834–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segú Odriozola, M.; Gómez-Quintero, J.D.; Casado Patricio, E.; Aurrekoetxea-Casaus, M. Visados para soñar: Expectativas y emociones de adolescentes y jóvenes que migran solos/as. Migraciones 2023, 57, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjab-Boudiaf, H. Las Nuevas Generaciones de Personas Menores Migrantes. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/45098 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Garcia, M.F.; Birman, D. Understanding the migration experience of unaccompanied youth: A review of the literature. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2022, 92, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppedal, B.; Keles, S.; Røysamb. Subjective Well-Being Among Unaccompanied Refugee Youth: Longitudinal Associations with Discrimination and Ethnic Identity Crisis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 920657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alarcón, X.; Prieto-Flores, O. Transnational family ties and networks of support for unaccompanied immigrant youths in Spain: The role of youth mentoring in Barcelona. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 128, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béjar, M. Neuroeducación. Padres Y Maest./J. Parents Teach. 2014, 355, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.M.E.; Camargo, C.D.B.; López, R.Q. Claves de la Neuropedagogía; Ediciones Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liras, E. Menores extranjeros no acompañados y extutelados. Propuesta de intervención psicopedagógica. Reidocrea 2021, 10, 51–119. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Muñoz, M.Á.; Parra-González, M.E. Orientación Académica y Profesional a los Menores Extranjeros No Acompañados. Int. J. New Educ. 2021, 5, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Red Española de Inmigración y Ayuda al Refugiado. Informe Preliminar Sobre los Menores No Acompañados en la Comunidad de Madrid. 2019. Available online: https://redinmigracion.org/ (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Fiscalía General del Estado (FGE) (2020). Memoria. 2020. Available online: https://www.fiscal.es/memorias/memoria2020/Inicio.html (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- UNICEF. Informe Niños Migrantes no Acompañados. 2021. Available online: https://www.unicef.es/ninos-migrantes-no-acompanados (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- López-Belmonte, J.; López-Meneses, E.; Vázquez-Cano, E.; Fuentes-Cabrera, A. Avanzando hacia la inclusión intercultural: Percepciones de los menores extranjeros no acompañados de centros educativos españoles. Rev. De Educ. Inclusiva 2019, 12, 331–350. Available online: https://revistaeducacioninclusiva.es/index.php/REI/article/view/482 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Grimaldo-Santamaría, R.Ó.; Ruiz-Fincias, M.I. Perfilación espacial mediante aprendizaje no supervisado de la opinión que distintos colectivos profesionales tienen respecto a la población juvenil nativa y extranjera. Sociol. Y Tecnociencia Rev. Digit. De Sociol. Del Sist. Tecnocientífico 2021, 11, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Interior. Registro Menores Extranjeros. 2020. Available online: https://www.interior.gob.es/opencms/ca/servicios-al-ciudadano/tramites-y-gestiones/extranjeria/regimen-general/menores-extranjeros/ (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Francia, G.; Neubauer, A.; Edling, S. Unaccompanied Migrant Children’s Rights: A Prerequisite for the 2030 Agenda’s Sustainable Development Goals in Spain and Sweden. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, A.; Santos-González, I. Menores extranjeros no acompañados en España: Necesidades y modelos de intervención. Psychosoc. Interv. 2017, 26, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inofuentes, R.A.; De la Fuente, L.; Ortega, E.; García-García, J. Victimization and externalizing and antisocial behavior problems in unaccompanied foreign minors in Europe: Systematic Review. Anu. De Psicol. Jurídica 2021, 32, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguaded-Ramírez, E.M.; Angelidou, G. Menores Extranjeros no Acompañados. Un fenómeno relevante en la sociedad española. La perspectiva de los trabajadores en los centros de acogida. Rev. De Educ. De La Univ. De Granada 2017, 24, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley Orgánica 1/1996, de 15 de Enero, de Protección Jurídica del Menor, de Modificación Parcial Del Código Civil y de la Ley de Enjuiciamiento Civil. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 15, de 15 de Enero de 1996. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/1996/01/15/1/con (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Ley Orgánica 04/2000, de 11 de Enero, Sobre Derechos y Libertades de los Extranjeros en España y su Integración Social. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 10, de 11 de Enero de 2000. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2000/01/11/4/con (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Corella, Á.S.; Moreno, N.H. El controvertido procedimiento determinación de la edad: La necesidad de una reforma legal a partir de los dictámenes del Comité de Derechos del Niño. Rev. Estud. Eur. 2022, 80, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriani Cernadas, P. Los Derechos de los Niños y Niñas Migrantes no Acompañados en la Frontera sur Española; UNICEF Comité Español: Madrid, Spain, 2019; ISBN 978-84-948540-5-7. Available online: https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/oia/esp/documentos_ficha.aspx?id=5750 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Horno-Goicoechea, P.; Romeo-Biedma, F.J.; Ferreres-Esteban, A. El Acogimiento Como Oportunidad de Vida. Referentes de Buena Práctica y Recomendaciones Para Una Atención Idónea a Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes en Acogimiento Familiar y Residencial. UNICEF Comité Español. 2017. Available online: https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/oia/esp/documentos_ficha.aspx?id=5480 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Vinaixa-Miquel, M. La mayoría de edad: Un mal sueño para los menores extranjeros no acompañados. Cuad. Derecho Transnacional 2019, 11, 571–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-España, E. De menores inmigrantes en protección a jóvenes extranjeros en prisión. Indret Revista Para El Análisis Del Derecho 2016, 3, 4–23. Available online: https://www.raco.cat/index.php/InDret/article/view/314413/404527 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Dioses-Fernández, D.L.; Corzo-Sosa, C.A.; Zarate-García, J.J.; Vizcarra-Gonzales, V.A.; Zapata-Maza, N.G.; Arredondo-Nontol, M. Adherencia a la atención prenatal en el contexto sociocultural de países subdesarrollados: Una revisión narrativa. Horiz. Med. 2023, 23, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, I.M.C.; López-Soler, C.; Alcántara-López, M.; Sáez, M.C.; Fernández-Fernández, V.; Pérez, A.M. Consecuencias del maltrato crónico intrafamiliar en la infancia: Trauma del desarrollo. Papeles Del Psicólogo 2020, 41, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ténon, K.O.N.E. De la inversión de los roles tradicionales o el declive de un mito familiar africano en Las tinieblas de tu memoria Negra de Donato Ndongo-Bidyogo. Dialogos 2023, 23, 13–25. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1077798 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- León-Rodríguez, D.A.; Cárdenas, F.P. Interacción Genética-Ambiente y Desarrollo de la Resiliencia: Una Aproximación desde la Neurociencia Afectiva. Tesis Psicológica 2020, 15, 12–33. Available online: https://revistas.libertadores.edu.co/index.php/TesisPsicologica/article/view/990 (accessed on 9 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Solana, R.A. Funcionamiento Neurocognitivo en la Adolescencia: Relación con Factors de Ajuste Psicológico. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de La Rioja, Logroño, Spain, 2022. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=308726 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Sánchez, T. Síndrome de resignación. Trauma migratorio, somatización y disociación extremas. Apert. Psicoanalíticas 2020, 63, 3–23. Available online: https://www.aperturas.org/imagenes/archivos/ap2020%7Dn063a6.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Silva-Hernández, A.; López-Sala, A. Humanidad en vilo. Movilidad, emociones y fronteras. Migr. Int. 2023, 14, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starck, A.; Gutermann, J.; Schouler-Ocak, M.; Jesuthasan, J.; Bongard, S.; Stangier, U. The Relationship of Acculturation, Traumatic Events and Depression in Female Refugees. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floristán-Millán, E.; Marmié, C. Navegando el gobierno transnacional de la infancia y juventud en movimiento. Una doble mirada cruzada: Harragas y aventureros entre España y Francia. Soc. E Infanc. 2023, 7, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, E.A.; Smart-Richman, L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. Investigación con Estudio de Casos, 6th ed.; Ediciones Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolae, G.; Martínez, C.; Arnoso, A. Ajuste psicosocial en menores extranjeros no acompañados en centros de acogida y jóvenes extranjeros no acompañados en pisos de emancipación. Sociedad Española de Psicoterapia y Técnicas de Grupo 2016, 34, 61–73. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9241307 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).