Abstract

This study explores the feasibility of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT and Bard as virtual participants in health-related research interviews. The goal is to assess whether these models can function as a “collective knowledge platform” by processing extensive datasets. Framed as a “proof of concept”, the research involved 20 interviews with both ChatGPT and Bard, portraying personas based on parents of adolescents. The interviews focused on physician–patient–parent confidentiality issues across fictional cases covering alcohol intoxication, STDs, ultrasound without parental knowledge, and mental health. Conducted in Dutch, the interviews underwent independent coding and comparison with human responses. The analysis identified four primary themes—privacy, trust, responsibility, and etiology—from both AI models and human-based interviews. While the main concepts aligned, nuanced differences in emphasis and interpretation were observed. Bard exhibited less interpersonal variation compared to ChatGPT and human respondents. Notably, AI personas prioritized privacy and age more than human parents. Recognizing disparities between AI and human interviews, researchers must adapt methodologies and refine AI models for improved accuracy and consistency. This research initiates discussions on the evolving role of generative AI in research, opening avenues for further exploration.

1. Introduction

In the past year, artificial intelligence (AI) technologies and, more specifically, large language models (LLMs), have evolved significantly after a decade of moderate successes [1]. Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer (ChatGPT), a prominent example of this technology, is designed as a trillion-parameter natural language processing model identified as GPT-4. It is a transformer model which uses deep learning algorithms and is trained through a combination of supervised and reinforcement learning on a petabyte-scale dataset [2]. As such, ChatGPT is able to generate human-like responses across a broad spectrum of user prompts [3,4]. Its immense potential is apparent in various applications, such as chatbots, customer service, education, research, and even healthcare [3,4,5,6].

Currently, major technology companies are engaged in a competitive race to release their own large language models, including AI-chatbots like OpenAI’s (San Francisco, CA, USA) ChatGPT (based on GPT-4) and Google’s (Mountain View, CA, USA) Bard (based on LaMDA), with broad applications [7]. Meanwhile, smaller companies and academic groups have started to explore the potential of these models in specific areas of research, including healthcare education and clinical practice [2,8,9,10].

Given their ability to emulate human-like conversations and access vast amounts of data, these technologies are poised for further exploration in several research areas and methodologies, including qualitative research [4,6,11]. Qualitative research, in contrast to quantitative research, focuses on the “why” rather than the “what” of studied phenomena [12]. Widely employed in the social and psychological sciences, qualitative research provides researchers with an in-depth understanding of phenomena within their natural settings [13]. It is based on a process of naturalistic inquiry (in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, etc.) and assesses the lived experiences of human participants and their subjective understanding of these experiences. Despite rigorous methodology, qualitative research is susceptible to recall bias, social desirability bias, observer bias, etc. [12,13,14]. Although researchers can mitigate some biases through awareness, eliminating all biases stemming from the subjective context of participants remains challenging [12].

Early evidence already indicates that an LLM trained on extensive datasets of texts and images collected from the internet, with additional fine-tuning using reinforcement learning based on human feedback, could approximate a “collective knowledge platform” or even a “collective subconsciousness” [4]. This model might demonstrate human-level performance in research tasks such as qualitative interviews [4,5,15], although it was not originally designed for such purposes. To support this notion of near-human behavior in some instances, a large-scale study by Herbold et al. [5] showed that ChatGPT-generated argumentative essays consistently received higher quality ratings from teachers than those written by humans.

However, less is known about the way AI can act as a participant in a study geared to a specific topic, rather than reproduce knowledge or complete a specific assignment [4,5]. Nonetheless, examining the role of AI as a participant in qualitative interviews is critical due to the potential for fraud and misuse by researchers [5]. As AI technologies become more sophisticated, there is an increased risk that researchers might exploit these tools to manipulate or fabricate data, posing a threat to the integrity and credibility of scientific research [2,3]. Transparency regarding the use of AI and clearly distinguishing between AI-generated and human-generated data are essential in order to prevent misleading interpretations. Failure to do so can erode trust in research findings and compromise the credibility of the research process. Furthermore, ethical considerations extend to the development and deployment of AI models themselves [3]. Developers must adhere to ethical guidelines and principles, such as fairness, transparency, and accountability, to mitigate the risk of bias and ensure the responsible use of AI in research settings [4,5]. Monitoring and assessments of AI models’ performance are essential to identify and address potential ethical concerns. Additionally, AI models can perpetuate existing biases, further compromising research validity [5]. Safeguards such as transparency and robust validation procedures are necessary to maintain research integrity in the face of evolving AI capabilities [4,5,8].

Conversely, AI also provides tremendous opportunities for qualitative research. The language processing capabilities of AI can enhance language understanding in qualitative research. AI models can help researchers to discern nuances, sentiments, and contextual meanings in text, enabling a more in-depth analysis of human participants’ responses [7]. This can be particularly valuable in understanding subjective experiences and viewpoints. Additionally, AI language models equipped with multilingual capabilities offer the opportunity to conduct cross-lingual qualitative research. This can be beneficial in transcending language barriers, allowing researchers to explore diverse cultural perspectives and enriching the depth and breadth of qualitative studies.

Study Aims

The main goal of this study is to explore the way in which LLMs can act as qualitative research participants, and how their responses in in-depth interviews on a complex subject compare to human responses. This type of design has, to our knowledge, not been tested in empirical research to date [16,17,18]. To achieve this, we devised a context in which two LLMs were used as virtual participants in semi-structured interviews. Our evaluation focused on assessing the performance of these platforms, comparing the outcomes with the themes and concepts derived from a parallel study involving human participants, which was conducted in 2022 [19].

2. Materials and Methods

This study drew inspiration from and builds upon the foundational research conducted by Donck et al. [19] on parental perspectives on adolescent health-related confidentiality. Diverging from the conventional recruitment of human participants, our methodology incorporated two advanced AI models: ChatGPT-4 (version 3, August 2023) and Bard (version 13, July 2023). This deliberate choice, driven by their public availability and status as the two largest LLMs, facilitated a comparative analysis of the outputs generated by these models against the findings of Donck et al. [19]. Opting for two distinct AI models was a strategic decision, enabling a broader range of responses and facilitating an in-depth exploration of each model’s capabilities and potential limitations.

AI personas were generated based on the same participant profiles that were recruited in the study by Donck et al. [19]. This approach ensured consistent representation in terms of age, gender, marital status, and parental status. The interactive sessions, designed to simulate online interviews, faithfully mirrored the conditions of data collection established in the original study [19].

In our methodology, we adapted original cases from Donck et al. [19] into prompts tailored to be compatible with the selected AI platforms. Twenty AI-generated participants (ten AI mothers and ten AI fathers, aligning with Donck et al. [19]) were engaged in simulated interview sessions that replicated the conditions of the original study. These sessions revolved around four cases related to potential areas of disagreement between parents and children in medical treatment scenarios. These cases, developed collaboratively by a team of pediatricians and sociologists, focused on confidentiality issues within the physician–patient–parent triad in the context of alcohol intoxication, sexually transmitted disease (STD), ultrasound without parental knowledge, and mental health issues (see Appendix A for an overview of the cases). After presenting each case, AI participants were queried about their opinions on whether a physician should share information with them, even if the adolescent requested confidentiality. Consistent inquiries were made regarding the potential influence of the age and sex of the adolescent, as well as distinction between a general practitioner and a specialist. Responses from the AI models were recorded and stored in a separate database. All interactions, including those with the AI models, were conducted in Dutch, and the entire AI interview cycle took place in August 2023. Instances where ChatGPT-4 or Bard struggled to produce a response were terminated, prompting the initiation of a new interview.

The initial phase of data analysis involved open coding, wherein interview outcomes were distilled into summarized concepts. To bolster research robustness and mitigate biases, interviews conducted with ChatGPT and Bard were independently coded by two-person research groups. Collaboration within these groups was integral to the coding process [20]. Subsequently, the axial coding phase was initiated to formulate overarching categories that encompassed all of the interview data for each AI model. In the final selective coding phase, the connections identified earlier were validated through discussions that involved comparing included and omitted data [21]. This coding approach resulted in the identification of primary themes related to confidentiality: etiology, privacy, responsibility, and patient characteristics.

After completing data collection and analysis, the concepts from ChatGPT-4 and Bard were compared with those from the original study [19]. A matrix was established to juxtapose primary themes from AI-assisted interviews with those from the human participant study, providing a tangible framework for pinpointing commonalities and differences. For an overview of key quotes by both AIs and human participants, see Appendix B.

3. Results

The analysis revealed three primary themes in the interviews with ChatGPT and Bard: (1) privacy, (2) trust, and (3) etiology of the health problems. These themes, along with their corresponding subthemes, are detailed below. Although ChatGPT and Bard generated similar concepts, there were nuanced differences in their meanings, and they placed varying emphasis on specific concepts.

3.1. Trust

3.1.1. Between Parent and Physician

In ChatGPT’s responses, the relationship between parents and physicians took a backseat, garnering prominence only in cases of depression. Here, AI-parents consistently utilized their connection with the physician to foster openness in their child. Notably, AI-parents placed trust in the physician’s judgment, particularly that of a general practitioner, concerning matters of privacy. The significance of the physician maintaining a positive relationship with the adolescent stood out, underlining the general practitioner’s insight into family dynamics.

Conversely, this relationship emerged as the most significant in Bard’s responses. The physician was frequently relied upon not just for professional advice, but also to guide parents on how to approach discussions with their child, particularly in cases involving alcohol use.

3.1.2. Between Adolescent and Physician

In ChatGPT’s responses, the relationship between the adolescent and the physician was deemed crucial, especially in cases of STDs and alcohol abuse. AI-parents expected physicians to furnish accurate information to their child about associated risks, promoting safe engagement. Open communication between the adolescent and physician was encouraged, and if the child could not be persuaded to confide in the parent, the preference was for the physician to respect the child’s privacy.

Conversely, Bard placed less emphasis on this relationship, mentioning it infrequently, primarily in cases involving alcohol use and STDs. Privacy and the expectation for the child to seek help in the future took precedence in Bard’s considerations.

3.1.3. Between Parent and Adolescent

In ChatGPT’s responses, the parent–adolescent relationship gained prominence in the context of alcohol abuse. AI-parents aspired to establish a robust connection with their child, encouraging the adolescent to willingly share information. The primary objective was to provide support to the child.

On the other hand, this relationship held less prominence in Bard’s responses, being mentioned solely in the case of alcohol use.

3.2. Etiology

3.2.1. Severity

In ChatGPT’s interactions, the inclination of AI-parents to seek additional information from their child heightened as the medical situation became more severe. There was a common assumption by ChatGPT that treatment by a specialist indicated a more serious issue. This emphasis on severity was also evident in discussions about STDs. Conversely, in Bard’s responses, the consideration of severity, while mentioned in the context of STDs, leaned toward advocating for physicians to inform parents, regardless of the severity of the situation.

3.2.2. Safety

Safety considerations were uniquely highlighted by Bard. Especially in cases of alcohol use and STDs, Bard emphasized safety, focusing on the well-being of the adolescent and protecting them from potentially dangerous situations.

3.2.3. Frequency

ChatGPT’s responses uniquely highlighted the influence of the increased frequency of an issue. AI-parents became more willing to let the physician breach the child’s privacy, a phenomenon particularly noted in the case of alcohol abuse.

3.2.4. Risks

In the evaluation of risks, both ChatGPT and Bard demonstrated comprehensive considerations. Risks, encompassing physical, psychological, emotional, and social aspects, were weighed by both models. ChatGPT provided nuanced insights, acknowledging various dimensions of risks and their potential impact on the adolescent’s development.

3.3. Privacy

The level of privacy a child is entitled to, according to ChatGPT, is contingent upon the child’s age and demonstrated level of responsibility. The degree of privacy afforded to the child is directly linked to their capacity to handle it. The greater the level of responsibility parents attribute to the child, the greater the degree of privacy the child will receive. This perspective posits that the concept of privacy is not static, but rather dynamically evolving in consonance with an individual’s age and corresponding expectations of personal autonomy and responsibility.

Bard’s understanding of privacy included age and legal implications, with occasional confusion regarding age distinctions. The age limit for parental notification varied, often aligning with legal adulthood at 18, but with exceptions based on specific cases such as alcohol use, since the minimum age for alcohol consumption in Belgium is 16. Thus, we can conclude that Bard did not truly grasp the meaning of the concept of ”privacy”, although it was a word frequently used throughout all of the interviews.

3.4. Differences in Responses between LLMs and Human Participants

The primary distinctions between the responses generated by ChatGPT and Bard and those from human participants were most evident in their treatment of the concept of “privacy”. Both ChatGPT and Bard addressed privacy, albeit with distinct nuances, whereas this aspect was notably absent in human responses. In ChatGPT’s outputs, privacy emerged as a complex concept intricately tied to the developmental stage of adolescents and the level of responsibility entrusted to them. Bard’s responses, on the other hand, also incorporated age considerations, but the legal framework played a more prominent role in shaping decision making, a facet less emphasized in ChatGPT’s outputs. In both instances, the degree of adolescent responsibility correlated with an escalation in the confidentiality maintained between the doctor and the adolescent.

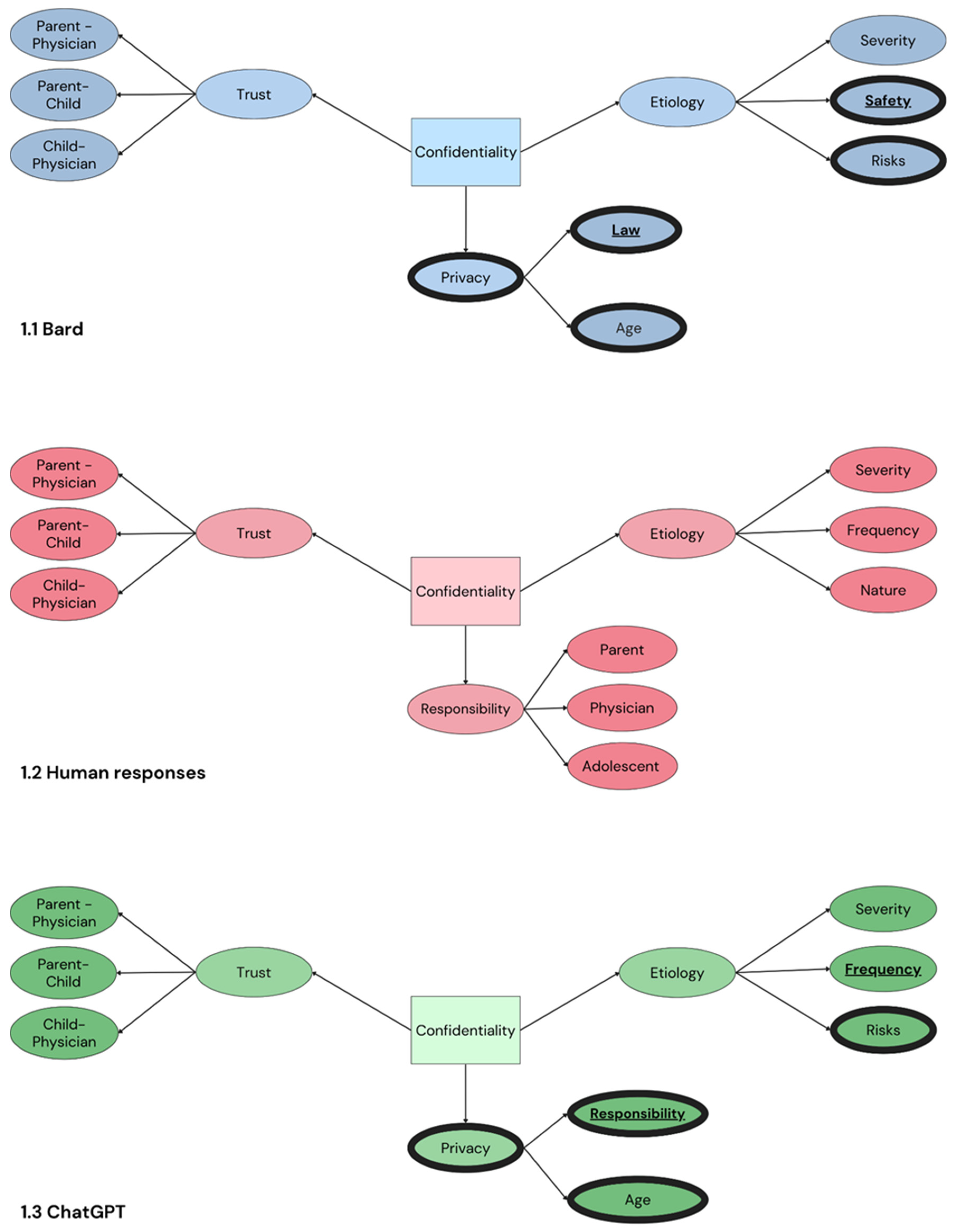

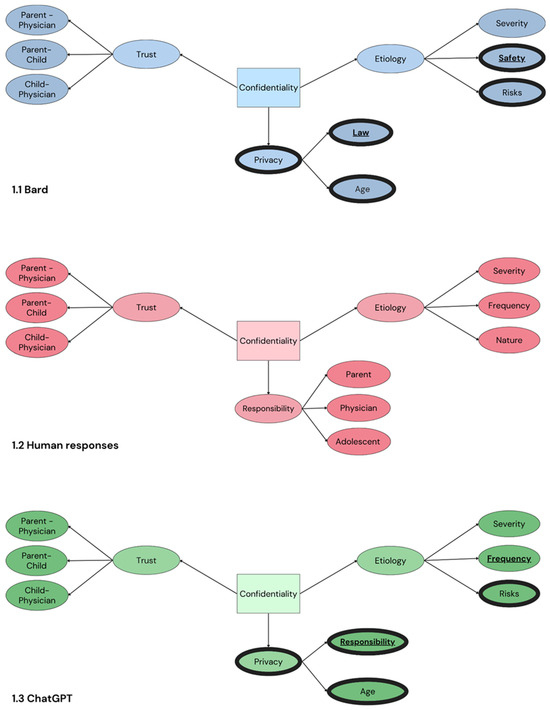

Nuanced differences also surfaced in the discussion of etiology, as depicted in Figure 1. A consistent aspect raised by human parents, but absent in both ChatGPT’s and Bard’s responses, pertained to the nature of the issue, distinguishing between physical and mental health concerns. Intriguingly, risks, delineated as a separate category within etiology, were absent in the human responses but featured prominently in both ChatGPT’s and Bard’s outputs. These responses spanned physical risks as well as risks to mental, emotional, and social well-being.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the main themes of parental perceptions regarding adolescent confidentiality in AI and human participants.

In contrast to Bard’s responses, both ChatGPT and human perspectives addressed the frequency of incidents as a subcategory within etiology, with particular emphasis on cases involving alcohol intoxication. The frequency of incidents influenced parental expectations, with a higher incidence leading to a diminished expectation of confidentiality, as parents expected to be informed. Bard’s responses, especially regarding alcohol-related cases, placed heightened emphasis on legal considerations and the trust dynamic between the physician and the parent.

Across both human and ChatGPT responses, the central focus on trust within relationships was observed primarily in the context of the physician–adolescent relationship. Parents recognized this relationship as pivotal, acknowledging that a breach of trust could potentially leave adolescents feeling isolated and unsupported. In Bard’s responses, while the physician–adolescent relationship remained significant, it was grounded more in medical confidentiality than trust. Notably, the parent–physician relationship, frequently highlighted by Bard, was not as prominently featured in ChatGPT or human responses.

4. Discussion

The inclusion of AI as a participant in qualitative research raises profound questions regarding the reliability and ethical implications of AI-generated data. It also prompts inquiries into AI’s capacity to mimic human emotions and the potential for AI to enrich the research experience.

4.1. Using AI Models in Qualitative Research, with a Focus on Adolescent Health-Related Confidentiality

Upon examining the current performance of AI models, they demonstrate the capability to simulate human responses during interviews. This aligns with previous findings which indicate that AI can perform as well as, or even better than, humans in knowledge reproduction [4,5,15]. Notably, both ChatGPT and Bard share underlying concepts with human interviewees. However, nuances in these concepts (and their subcategories) and the frequency with which they are used warrant further discussion.

Our analysis compares responses from ChatGPT and Bard with those from human participants on adolescent health-related confidentiality, focusing on themes of trust, etiology, and privacy within parent–physician–adolescent interactions. Distinct patterns emerged:

4.1.1. Trust Dynamics

In parent–physician relationships, ChatGPT emphasizes trust in the physician’s judgment, while Bard positions the physician as a guide, extending beyond professional advice. ChatGPT stresses open communication between adolescents and physicians, whereas Bard places less emphasis on this, prioritizing privacy. Parent–adolescent relationships are highlighted by ChatGPT, especially in alcohol abuse cases, whereas Bard mentions it only in the context of alcohol use.

4.1.2. Etiological Considerations

Regarding severity, ChatGPT notes parents seeking more information with increased severity, while Bard advocates for physician–parent communication irrespective of severity. Safety is explicitly highlighted by Bard, especially in alcohol and STD cases, while ChatGPT does not explicitly address safety. ChatGPT uniquely highlights the influence of frequency, particularly in alcohol abuse cases, while Bard focuses more on legal considerations and trust dynamics.

4.1.3. Privacy Dynamics

ChatGPT views privacy dynamically, linked to the child’s age and responsibility level, evolving with individual development. Bard’s understanding includes age and legal implications, but occasionally exhibits confusion. Differences from human responses include the absence of privacy emphasis and risks in human responses, present in both ChatGPT’s and Bard’s outputs.

4.1.4. Overall Differences

While trust within relationships, especially physician–adolescent dynamics, is central, there are notable differences in emphasis. The AI models and human participants differ in their treatment of privacy and risks, offering unique perspectives on parent–physician–adolescent interactions. Indeterminate responses occurred more frequently with Bard than with ChatGPT-4. Despite both AI models being categorized as large language models [22], their unique algorithms and training datasets yielded different insights, enhancing the value of comparing their outputs. The lack of transparency from OpenAI and Google regarding the training of their LLMs poses challenges for researchers attempting to comprehend the inner workings of these models. Utilizing AI models such as ChatGPT and Bard in these types of studies also introduces the possibility of biases that can impact the data’s quality and interpretation. These models are trained on extensive datasets that may inherently contain biases from the data sources. For instance, if the training data predominantly represent specific demographics or cultural viewpoints, the resulting AI-generated responses may mirror these biases, potentially skewing or inadequately representing the topic under examination. The language used in this study, Dutch, may have also introduced biases, as nuances and complexities in other languages could yield different outcomes.

4.2. Distinguishing AI and Human Interviews

Interviewing AI and humans reveals differences in several aspects. Firstly, the design of prompts and questions for AI necessitates clear, text-based inquiries. This formality arises from AI’s dependence on precise input for generating meaningful responses. In contrast, human interviews often adopt a more fluid and open-ended approach, adapting to interpersonal communication dynamics [12]. Significant distinctions emerge in the foundation of responses. AI relies heavily on factual knowledge and data, while human responses are more emotion-based, reflection a nuanced understanding beyond mere factual recall. In terms of consistency, AI often provides identical or highly similar answers to the same input, whereas human interviews exhibit a range of interpersonal differences. AI-generated responses tend to be lengthier and more formal, offering intricate details and explanations. Human responses, on the other hand, may be more concise, tailored to the complexity of the question or their ability to articulate thoughts effectively.

4.3. Limitations of AI Models in Qualitative Research

When evaluating the use of AI models, particularly Bard, several limitations came to the forefront. Bard exhibited inconsistency, forced phraseology, and a tendency towards non-answers—particularly in more sensitive cases involving STDs and depression. Its struggle to produce original responses and overreliance on legal interpretations hindered us from obtaining meaningful information. Specificity challenges, like determining an age for independent medical decisions, were evident in Bard, but not as pronounced in either ChatGPT or human participants. ChatGPT demonstrated infrequent errors and occasional non-responses, particularly during questions about sensitive topics like STDs. Unlike Bard, ChatGPT’s dependency on the law was less pronounced, showing a better understanding of age-related nuances.

A common shortcoming of LLMs is factual correctness. Due to their static nature and predictive word generation, natural-sounding sentences may lack accuracy. Stereotypes were occasionally found in Bard’s responses, indicating a need for refining its adherence to non-discriminatory principles. Inconsistency, particularly in Bard, manifested in conflicting statements within a single response. ChatGPT, in contrast, displayed a higher level of consistency, with well-constructed sentences and explanations.

4.4. Future Perspectives

This proof of concept highlights similarities between human and LLM responses, raising ethical discussions about the use of these new technologies in qualitative research. Future considerations should include the performance of AI models in emerging topics such as COVID-19 or the AI revolution, where human opinions may evolve before being accurately reflected in AI models. Additionally, investigating the “cultural bias” of AI models, which are often developed by American companies, poses an intriguing avenue for exploration. Integrating AI models into qualitative research has the potential to influence interview dynamics, communication skills, and participant comfort. For instance, the use of AI in interviews may alter the interaction dynamic between researchers and participants, potentially affecting rapport building and the depth of responses. Moreover, participants may perceive interactions with AI differently than with humans, impacting their comfort level and willingness to disclose sensitive information. Additionally, researchers may need to adapt their communication strategies when interacting with AI, ensuring clear and precise prompts to elicit meaningful responses.

The notable struggle of AI models, particularly in addressing sensitive topics, brings to light future challenges in their application. These challenges manifest in limitations observed during discussions on subjects like STDs and depression. The nuanced nature of human emotions, the complexity of personal experiences, and the ethical considerations surrounding sensitive topics pose difficulties for AI models. In these instances, AI models, such as Bard and ChatGPT, exhibited limitations such as non-answers or occasional errors. This underscores the current boundary of AI in fully grasping the intricacies of human emotions and experiences. The nature of sensitive topics often involves nuanced understanding, empathy, and context, elements that may be challenging for AI models to comprehend fully. It remains an open question whether LLMs will be able to successfully address these issues in the future.

4.5. Broader Implications

The study of the integration of artificial intelligence into qualitative research has broader implications that extend beyond the specific findings discussed. Most importantly, there are considerable ethical concerns regarding the use of AI in research, particularly concerning the reliability of AI-generated data and the potential mimicry of human emotions. Researchers and institutions need to establish ethical guidelines and frameworks to ensure the responsible and transparent use of AI in qualitative research.

The differences observed between AI and human interviews suggest that researchers need to be aware of the potential of employing AI in qualitative studies. This involves recognizing the formal nature of AI responses, understanding the differences in response foundations, and considering the potential impact on the richness and depth of qualitative data. Our identification of limitations in AI models, such as inconsistency, forced phraseology, and susceptibility to non-answers, highlights the need for continuous refinement of these models. AI developers should address these issues to improve the accuracy, consistency, and overall performance of AI in qualitative research contexts.

In summary, this study not only provides insights into the specific challenges and potentials of integrating AI into qualitative research, but also serves as a catalyst for broader discussions and considerations in the evolving landscape of AI research methodologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F., E.L., L.M., A.W. and J.T.; methodology, J.F., E.L., L.M. and A.W.; software, J.F., E.L., L.M. and A.W.; validation, J.F., E.L., L.M. and A.W.; formal analysis, J.F., E.L., L.M. and A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F., E.L., L.M. and A.W.; writing—review and editing, S.V.D., D.D.C. and J.T.; supervision, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. David De Coninck was supported by funding from the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) with grant number 1219824N (DeMiSo).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results can be provided by the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Fictional Cases Presented to AI and Human Participants

Appendix A.1. Case 1

Your son went to a party with friends and drank alcohol. Afterwards, he tripped and fell on the floor and unfortunately ended up with his hand in a glass shard. Because of this injury, he was taken to the emergency room where a doctor stitched the wound. Your son realizes that he will be in trouble when you (as a parent) will hear about the intoxication and asks the attending physician not to inform you about it.

Which decision do you believe the physician should make?

□ The physician reports the intoxication to the parents.

□ The physician does not report the intoxication to the parents.

Appendix A.2. Case 2

Your daughter has recently started a romantic relationship and has an annoying problem for which she goes to the general practitioner. They diagnose a sexually transmitted disease (STD), which is easy to treat without side effects. She asks the practitioner not to say anything to you (the parents) about this infection.

Which decision do you believe the physician should make?

□ The physician reports the infection to the parents.

□ The physician does not report the infection to the parents.

Appendix A.3. Case 3

You received a hospital bill in the mail this week for an abdominal ultrasound performed on your son. You ask about the reason for this, but your son will not say. You contact the general practitioner who made the request for this examination and ask for the reason for this examination.

Which decision do you believe the physician should make?

□ The physician reports the reason for the examination to the parents.

□ The physician does not report the reason for the examination to the parents.

Appendix A.4. Case 4

In recent weeks you have noticed that there is a problem with your daughter: she sleeps poorly, always retreats to her room, doesn’t talk to her friends anymore, is often in a gloomy mood and eats badly. You know that your daughter went to the general practitioner for this a few days ago, but you do not know what was discussed there.

Which decision do you believe the physician should make?

□ The physician reports the findings to the parents.

□ The physician does not report the findings to the parents.

Appendix B. Key Quotes of in-Depth Interviews with AI and Human Participants

Table A1.

Key Quotes from Human Participants and AI per Theme.

Table A1.

Key Quotes from Human Participants and AI per Theme.

| Human Participants | ChatGPT | Bard |

|---|---|---|

| Trust between parent and physician | ||

| I would expect that our own family physician will be more likely to provide me with information [compared to a specialist], because of the established relationship of trust. (Parent K) | Ideally, the physician would be able to convince my daughter to talk to me herself or meet with me with her. As a parent, I would want to work with the physician to make sure my daughter gets the help she needs. (16.4) | I would also ask the physician for advice about how I can talk to my son about his care. (4.4) |

| Obviously, I would trust the information from the family physician a little bit more than from a physician that I do not know at all. (Parent D) | A general practitioner often has known the family and the patient for years and therefore has a deeper understanding of the family dynamics. There is an existing relationship of trust. (15.2) | I trust my physician’s judgement and I know he will always put my own interests first. (1.1) |

| Ideally, the physician would be able to convince my daughter to talk to me herself or meet with me with her. As a parent, I would want to work with the physician to make sure my daughter gets the help she needs. (16.4) | If the physician were my general practitioner, I’d probably take into account the fact that he or she has known my child for a long time and he or she probably has a better understanding of my concerns. I’d also be more likely to follow his advice. (19.4) | |

| Trust between physician and adolescent | ||

| I would hate for that [physician informing the parents] to stop her [to ask for help]. (Parent U) | It is essential that adolescents have confidence in their doctor and that they feel comfortable speaking openly about their health problems without fear of judgement or reprisal (3.1) | |

| It may also be important for the [minor] to have a confidant separate from the parents. (Parent C) | ||

| The risk [of asking the physician for information] is that [the minor] will not go to that physician anymore, because their trust was violated there. (Parent N) | ||

| Trust between parent and adolescent | ||

| We are a warm-hearted family, with open communication. Here, we tell each other [about it]. (Parent L) | My greatest hope would be that, despite her decision not to tell me directly, she eventually feels comfortable enough to discuss it with me or her mother so that we can support her. (11.1) | If you give your child their privacy, you build a bond with them which is stronger than any secrecy. (13.2) |

| For me, the physician does not need to call me, I will find out from my own son or daughter what happened. (Parent B) | But I believe that creating an environment of trust and respect is the best way to ensure that my children feel comfortable coming to me with their concerns and problems when they are ready. (1.2) | I don’t want my son to feel forced to lie to me, and I don’t want him to be afraid of the consequences of his actions. (13.2) |

| I would prefer to hear it all in detail, but if my daughter indicates that she would rather solve it in confidence with the physician, then I do not think that they [the physician] should say it. (Parent M) | ||

| Etiology (severity) | ||

| I think the doctor should report or say why the ultrasound took place. I would be anxious that it might be in response to a potentially serious illness or incurable disease. (Parent C) | A specialist would likely have more specific or deeper expertise in a particular area, and that may increase my concerns about the severity or complexity of the medical issue. (5.1) | The physician has to take all relevant factors into consideration, including the adolescent’s age, the nature of the situation and the risk of harm. (1.1) |

| Of course, it also depends on the severity. (Parent X) | For me as a parent, it would depend on the nature and severity of the medical situation. When it comes to issues that could threaten my child’s life or long-term health, regardless of their age, I would want the doctor to inform me. (3.1) | Nevertheless, if the STD were serious, I might ask to physician to inform me, so that we could make a plan to limit the risks. (15.2) |

| This could be the case if the child has thoughts of suicide or if the child were abused. (20.4) | ||

| Etiology (frequency) | ||

| If that happens systematically or gets completely out of hand, then it’s important to inform the parents. (Parent Z) | If I noticed a pattern of risky behaviour, I would want to intervene and support my child. But if this was a one-time misstep, I would also want to respect my child’s privacy. It’s a difficult balance. (1.2) | |

| If that happens once and they ask not to report it, okay. [If] this is the second or the third incident, then the physician should inform the parents. (Parent O) | ||

| Etiology (risks) | ||

| On the other hand, given the severity of the symptoms and my role as her guardian, I would hope that the doctor would approach me if he or she believes there is a serious risk to her health or well-being. If it’s something that requires immediate action or support, it’s crucial that I, as a parent, am informed. (2.4) | If I weren’t informed about my child’s STD, I think there are extra risks. My child could transmit the STD to other people, including his/her sexual partners and myself. My child could also encounter health problems if he/she doesn’t get the correct treatment. I’d also be worried about my child’s mental and emotional health. If my child has an STD, it can have a big impact on his/her self-image and self-esteem. I want to make sure my child gets the support and guidance he/she needs to get through this difficult time. (9.1) | |

| If the doctor feels that there is a serious risk to my son, such as suicidal thoughts or self-harm, then I believe it is absolutely necessary to share this with me as a parent. In such critical situations, it is vital that the family is informed and can take the appropriate steps to provide assistance. (4.4) | ||

| Etiology (safety) | ||

| I understand my child could get in trouble if I know that he/she drunk, but I think his/her safety is more important (9.1) | ||

| It’s important that parents support their children and help them to make safe sexual choices. (20.2) | ||

| As a parent of a 14 year old daughter I’d be worried about her safety in a few different ways. Firstly, I’d be worried that she could end up in a dangerous situation if she’s drunk. For instance, she could be hit by a car, she could fall and hurt herself, or she could be sexually assaulted. Secondly, I’d be worried she could make wrong decisions if she’s drunk. For example, she could leave with someone she doesn’t know, or she could do something that could land her in trouble. Thirdly, I’d be worried about the impact alcohol could have on her development. Alcohol can damage an adolescent’s brain, which can make it more difficult to learn and develop. (15.1) | ||

| Etiology (nature) | ||

| I do think that a child who does not feel comfortable in their own skin [psychological problem], is much more important than a physical problem that can be solved medically. (Parent N) | ||

| This is indeed a psychological problem, which makes this case a little more difficult. A mental health problem is always more difficult. (Parent D) | ||

| It depends on the child, on the situation, on the relationship of trust, on the nature of the contamination or infection. (Parent V) | ||

| Responsibility of the parents | ||

| I think that under the age of 18, it is still your job as a parent to guide them and, if something goes wrong, to make them aware of their actions and how to solve their problems. (Parent R) | ||

| We have full responsibility over our children, on every level. So yes, I would want that to be reported to me. (Parent K) | ||

| Responsibility of the adolescent | ||

| I think everyone has the right to commit one or a few mistakes. If you give your child a number of norms and values and they cross the line, they might learn a lot from it. (Parent O) | ||

| The youth should be allowed to experiment and test their limits. (Parent H) | ||

| Responsibility of the physician | ||

| But if the physician chooses not to communicate this to the parents, I think that he needs to take over a part of the parental role from the parents. I perhaps expect too much. But I expect that he takes care of the problem, that he pays attention to prevention and that he also gives her at least some advice. (Parent A) | ||

| Hopefully, we can assume, especially at that young age, that the GP will sound the alarm if something needs to be discussed. (Parent H) | ||

| Age | ||

| The younger the child, the more active and direct my involvement and concerns would be. With a younger child, I would also expect the doctor to be more open with me as a parent. (7.4) | This is because 13 year olds are old enough to make well-thought-out decisions about their own body and own privacy. Yes, I think the child in the aforementioned case is old enough to make decisions about his own health. This is because he is 13 years old and has reached a cognitive and emotional development which enables him to make well-thought-out decisions. He is also able to cope with the stress of making decisions about his own health. (13.3) | |

| At that age, children are generally less mature and less able to make fully informed decisions about their health. (3.3) | My daughter is still a minor and she is not capable to fully understand the consequences of her decisions. (19.3) | |

| The balance between the child’s privacy and the parent’s right to know shifts as the child grows older, and what is acceptable or expected for a 13-year-old child may not be the same as for a 16-year-old. (3.3) | For example, in the case of the 16-year-old daughter, I would be more mindful of her privacy than if she were 17 or 18 years old. This is because at 16 she already has more developed autonomy and can take more responsibility for her own health. (12.3) | |

| Privacy | ||

| Yes, the child’s age plays a crucial role in how I think about the situation. The older the child gets, the more I would respect their autonomy and privacy. (1.1) | ||

| Dependency on the law | ||

| Moreover, in Belgium, from the age of 12, young people have the right to request confidentiality from doctors about medical information, unless it poses a danger to the young person. (2.2) | In Belgium it is illegal for adolescents below 18 years old to drink alcohol. Adolescents aged 18 or older are allowed to drink alcohol, but there are limits to the amount of alcohol they can drink. (6.1) | |

| In most European countries, including Belgium, medical confidentiality is often protected for minors, especially as they get older. (13.2) | This is stipulated in the Medical Treatment Agreement Act (4.3) | |

| Correctness | ||

| I understand that there are differences between boys and girls. For example, boys are more often involved in violence and girls are more often a victim of sexual abuse. (1.1) | ||

| For example, some parents may worry that their son is not strong enough or athletic enough. Other parents may worry that their daughter is not feminine enough or does not get enough attention from boys. (16.4) | ||

| Consistency | ||

| In that case I’d trust the physician to do the best for my son and I’d try not to invade his privacy. I’d ask the physician to inform me about the reason for the ultrasound and I’d ask him for his advice about how I can talk to my son about it. (13.3) | ||

| If she does not want to tell me why she had the ultrasound done, I would respect her and respect her privacy. However, I would also call my daughter’s doctor to ask what the reason for the ultrasound was. (15.3) | ||

References

- Sun, L.; Yin, C.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, W. Artificial intelligence for healthcare and medical education: A systematic review. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 4820–4828. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, B.J.; McNeal, N.; Washington, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Sun, H.; Su, Y. Thinking About GPT-3 in-Context Learning for Biomedical IE? Think Again. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.08410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-alrazaq, A.; AlSaad, R.; Alhuwail, D.; Ahmed, A.; Healy, P.M.; Latifi, S.; Aziz, S.; Damseh, R.; Alrazak, S.A.; Sheikh, J. Large language models in medical education: Opportunities, challenges, and future directions. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e48291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagendorff, T.; Fabi, S.; Kosinski, M. Human-like intuitive behavior and reasoning biases emerged in large language models but disappeared in ChatGPT. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2023, 3, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbold, S.; Hautli-Janisz, A.; Heuer, U.; Kikteva, Z.; Trautsch, A. A large-scale comparison of human-written versus ChatGPT-generated essays. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: Systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. Healthcare 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Mehra, P.S. ChatGPT & Google Bard AI: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on IoT, Communication and Automation Technology, Gorakhpur, India, 23 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, G.; Horesh, N.; Brezinov, Y.; Meyer, R. Performance of ChatGPT in medical examinations: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. BJOG 2023, 131, 378–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z. Why and how to embrace AI such as ChatGPT in your academic life. R. Soc. Open Sci 2023, 10, 230658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savery, M.; Abacha, A.B.; Gayen, S.; Demner-Fushman, D. Question-driven summarization of answers to consumer health questions. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tustumi, F.; Andreollo, N.A.; Aguilar-Nascimento, J.E. Future of the language models in healthcare: The role of ChatGPT. Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 2023, 36, e1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hannes, K.; Lockwood, C. Synthesizing Qualitative Research: Choosing the Right Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, S.; McCarthy, G.; Sajib, S.; Michael, K.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; D’Ambra, J.; Shen, K.N. Algorithmic bias in data-driven innovation in the age of AI. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 60, 102387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, M.; McDonell, K.; Reynolds, L. Role play with large language models. Nature 2023, 623, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, D.L. Exploring the use of artificial intelligence for qualitative data analysis: The case of ChatGPT. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, P.A. The use of artificial intelligence (AI) in qualitative research for theory development. Qual. Rep. 2023, 28, 2739–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwin, J.; Chhabra, A.; Rao, V. Using large language models for qualitative analysis can introduce serious bias. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.17147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donck, E.; Devillé, C.; Van Doren, S.; De Coninck, D.; Van Bavel, J.; de Winter, P.; Toelen, J. Parental perspectives on adolescent health-related confidentiality: Trust, responsibility, and disease etiology as key themes. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doren, S.; Hermans, K.; Declercq, A. Conceptualising relevant social context indicators for people receiving home care: A multi-method approach in Flanders, Belgium. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e1244–e1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Casterlé, B.D.; Gastmans, C.; Bryon, E.; Denier, Y. QUAGOL: A guide for qualitative data analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ding, Y.; Sio, T.T.; McGee, L.A.; Ashman, J.B.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; Shen, J.; et al. Evaluating large language models on a highly-specialized topic, radiation oncology physics. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1219326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).