While the imaging of arteries and veins by CT, MRI, and angiography is standard practice in large and small hospitals as well as in outpatient practices in developed countries, the diverse and sophisticated radiological procedures for imaging lymph ducts are often unknown and available only in a few specialized institutions. The latter may be because the performance of so-called lymphangiography, i.e., the selective visualization of the lymph ducts including lymph nodes and lymphatic pathology using contrast material, requires expert knowledge and specific resources. In addition, the pathologies of the lymphatic system are much rarer compared to diseases of the arterial and venous systems, such that a sufficient number of cases has thus far only been encountered in centers for lymphatic disease. Nevertheless, in recent years, various radiological procedures have developed into highly clinically effective methods. The purpose of this Editorial is to highlight the clinically relevant aspects of lymphangiography. This perspective is based on the nearly 40 years of continuous experience of the three German Centers for Lymphatic Imaging and Intervention: Heidelberg University Hospital, the Stuttgart Clinics and Bonn University Hospital. In an emphatically pragmatic way, the indications, technical implementation, and results of the various approaches with respect to lymphangiography are explained and presented. In a concluding outlook, specific interventions for the minimally invasive treatment of lymphatic fistulas are discussed, among other topics

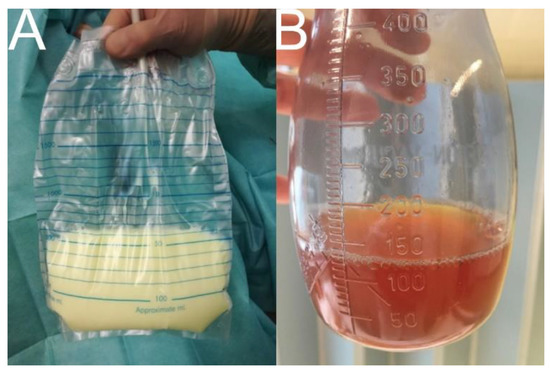

Lymphatic pathologies can be classified as iatrogenic or spontaneous [1,2]. Typical iatrogenic forms include postoperative lymphatic fistulae and lymphatic fistulae after chemotherapy (e.g., in patients with types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma such as chylaskos or chylothorax) [3]. The much rarer spontaneous lymphatic fistulas, which are typically diagnosed in babies, infants, and young children but can occur in the elderly, include complex lymphatic vascular anomalies and malformations as well as protein-loosing-enteropathy and plastic bronchitis [2]. Depending on the drainage volume, a distinction is made between high-output and low-output fistulas, with a threshold of 500 mL per day in adults (Figure 1) [1,2,4].

Figure 1.

Drainage fluid in high-output and low-output lymphatic fistulas. Note: (A) chylothorax (6000 mL per day) with milky appearance if patient does not follow a fat-free diet (drainage fluid typically contains chylomicrons, triglycerides > 110 mg/dL, total fat 0.4–6 g/dL, total protein 22–60 g/L, and a total cell count >1000 cells/L with >80% leucozytes); (B) iliac lymphocele (300 mL per day) with amber color.

A lymphatic fistula is a serious clinical problem for the affected patient and should never be underestimated. Uncontrollable dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, renal failure, protein loss, leukocyte loss, and superinfection are just a few of the dreadful complications. The consequences range from impaired quality of life, e.g., in patients with chronic low-output fistulas (multiple daily changes of wound dressings, months of dietary modification, or years of outpatient follow-up services), to death, typically in patients with acute high-output fistulas. From an emotional perspective, these aspects are dealt with as opportunities and challenges in a recent report published by Nature Research Custom Media (https://www.nature.com/articles/d42473-022-00400-x; accessed on 14 December 2022). The following aspects present a purely scientific approach that provides evidence for how lymphangiography can contribute to the diagnosis and treatment of these difficult-to-treat patient populations.

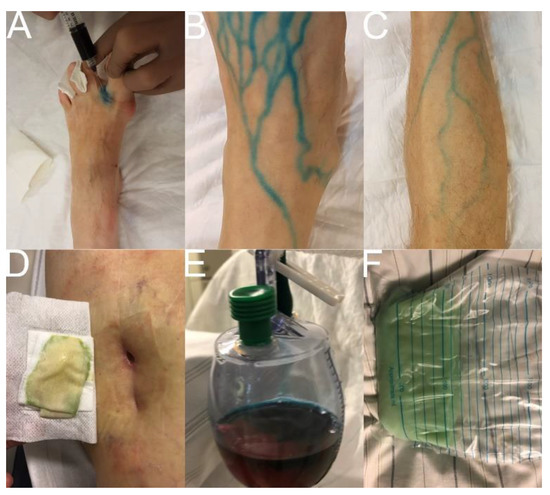

Lymphangiography is only indicated in refractory lymphatic fistulas, i.e., when conservative measures such as parenteral fat-free feeding, percutaneous drainage therapy, and repeated subcutaneous octreotide injections fail to achieve the desired clinical outcome [1,2,3]. In clinically unclear situations with a questionable persistence of lymphatic fistulas, e.g., under or after conservative therapy, the so-called Patent Blue test can be used. In this regard, the color change of the drainage fluid after a subcutaneous injection of Patent Blue into the first, second, and third interdigital spaces of the foot provides direct clinical evidence of the lymphatic fistula. In a broader sense, the Patent Blue test can be described as the simplest form of a lymphangiography, since, after the interstitial injection, the dye is mainly transported away centrally via the superficial lymph ducts, travelling from the lower extremities first via the groin and retroperitoneum to the cisterna chyli, and from thence via the thoracic duct to the left venous angle. If the aforementioned physiological lymphatic run-off is disturbed by a lymphatic fistula, pathological extravasation of Patent Blue is observed at the site of the fistula, thus providing visual evidence of the fistula (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patent Blue Test. Note: (A) subcutaneous injection of a 1:1 Patent Blue V/lidocaine 1% mixture in the first, second, and third interdigital spaces of the foot (1–3 mL each); (B,C) visualization of superficial lymph ducts at the lower extremity; (D) color change in percutaneous lymphatic fistula; (E) color change in lymphocele; (F) color change in chylothorax.

Lymphangiography can be offered either as “conventional lymphangiography” under radiographic control with an oil-containing contrast material (Lipiodol Ultrafluid; Guerbet, Villepinte, France) or as “MR lymphangiography” with a gadolinium-containing contrast material (e.g., Gadovist; Bayer, Germany) [2,5]. The decisive factor in both procedures is the selective and super-selective injection of the contrast material directly into the lymphatic system, as only in this way can high-resolution imaging of lymphatic pathology be achieved with the greatest possible accuracy.

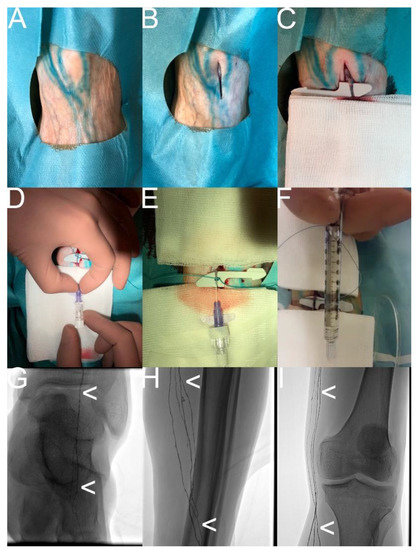

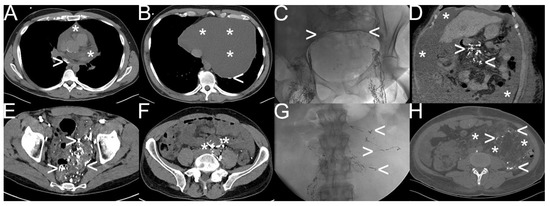

In “conventional lymphangiography”, the contrast material is injected either directly into a dissected and punctured lymph duct on the dorsum of the foot (“transpedal lymphangiography”) or into a lymph node after an ultrasound-guided percutaneous puncture, e.g., inguinal, retroperitoneal, axillary, or cervical (“intranodal lymphangiography”). The contrast material must be injected slowly at a flow rate between 0.07 and 2 mL per min, depending on the run-off capacity of the lymph duct. According to the instructions for use, the maximum dose of the oil-containing contrast material to be applied is 0.25 mL per kg body weight, but much higher doses have been reported in different clinical series [1,4,6]. Depending on the location of the lymphatic fistula, imaging by conventional radiography or CT is performed a few minutes to several hours following the contrast material’s injection [7]. While pathologic extravasation can be documented after only a few seconds to minutes for lymphatic fistulas in the groin, this direct radiological evidence of a lymphatic fistula can take several hours or even several days to appear in thoracic, cervical, or axillary locations. Figure 3 and Vid. 1 show the technique for “conventional lymphangiography” according to the protocol of the Stuttgart Clinics. Figure 4 and Figure 5 show different types of spontaneous and iatrogenic lymphatic fistulas detected by “conventional lymphangiography”.

Figure 3.

“Transpedal lymphangiography“—How it is performed. Note: (A) Patent Blue test; (B) sterile, cut-down of the dorsum of the foot; (C) selective dissection of a lymph duct; (D) selective puncture of the lymph duct with a 25 G baby cannula; (E,F) injection of the oil-containing contrast material; (G,H,I) confirmation of the regular distribution of the oil-containing contrast material (white arrowhead) in the central lymphatic system (corresponding to a regular lymphatic run-off).

Figure 4.

Different types of spontaneous lymphatic fistulas detected by “conventional lymphangiography“. Note: (A,B) etiologically unclear chylopericardium (white asterisk) with pathologic accumulation and extravasation of oil-containing contrast material (white arrowhead); (C,D) liver cirrhosis with chylous ascites (6000–8000 mL per day) (white asterisk) as a result of lymphatic congestion (white arrowhead) due to severe portal hypertension; (E,F) diffuse lymphatic malformation in the sigmoid and rectum visualized with oil-containing contrast material (white arrowhead) after bilateral “transpedal lymphangiography” due to reversed lymphatic run-off at the cisterna chyli flowing into the mesenteric trunk (white asterisk); (G,H) combined chylothorax, chylaskos, and chyloretroperitoneaum in a patient with tuberous sclerosis complex with atypical lymphatic run-off in the retroperitoneum as well (white arrowhead) due to giant angiomyolipoma (white asterisk).

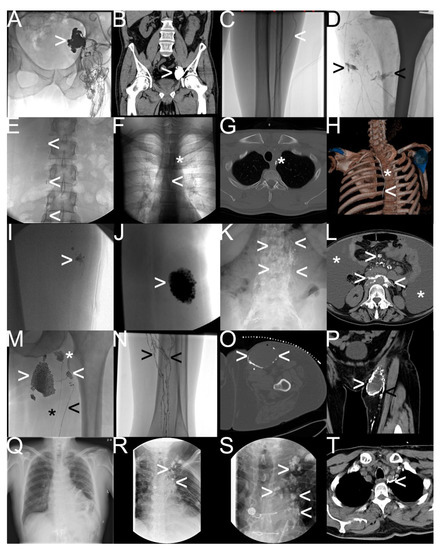

Figure 5.

Different types of iatrogenic lymphatic fistulas detected by “conventional lymphangiography“. Note: (A,B) after robot-assisted prostatectomy—iliac lymphocele (white arrowhead); (C,D) after total-knee arthroplasty—lymphatic feeder (white arrowhead) and percutaneous lymphatic fistulas (black arrowhead) leading to wound-healing disorder; (E–H) after radical thyroidectomy—mediastinal lymphatic fistula from the thoracic duct (white arrowhead) draining into the intraoperatively inserted drainage tube (white asterisk); (I,J) after soft tissue resection—typical lymphocele with blowout of oil-containing contrast material; (K,L) after chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma—chylaskos (white asterisk), and chylothorax with pathological accumulation of the oil-containing contrast material in retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymph nodes; (M–P) postoperative lymphocele (white arrowhead) and lymphatic feeder (black arrowhead) with impaired lymphatic run-off in the calf (black arrowhead) in contrast to a healthy lymph node (white asterisk) and a healthy lymph duct (black asterisk); (Q–T) after cardiac surgery—refractory chylothorax and chylopericardium with multifocal pathologic extravasation and accumulation of oil-containing contrast material in the mediastinum (white arrowhead).

“MR lymphangiography” is also divided into two forms: the first form, “interstitial MR lymphangiography”, entailing an intracutaneous injection of diluted contrast material containing gadolinium (e.g., 1:1 gadolinium/saline mixture) into the first, second, and third interdigital spaces of an extremity, and the second, “intranodal MR lymphangiography”, entailing an injection of a pure gadolinium-containing contrast agent typically into inguinal lymph nodes. Further information on the performance of “MR lymphangiography” can be found in the multiple publications of the Bonn University Hospital [5,8,9,10,11,12]. The advantage of “MR lymphangiography” is the possibility of high-temporal resolution dynamic imaging of even atypical lymphatic fistulas including tiny feeders; the disadvantage is the off-label nature of gadolinium-containing contrast material’s injection and the additional time required. Figure 6 and Figure 7 show typical findings of lymphatic fistulas in “MR lymphangiography”.

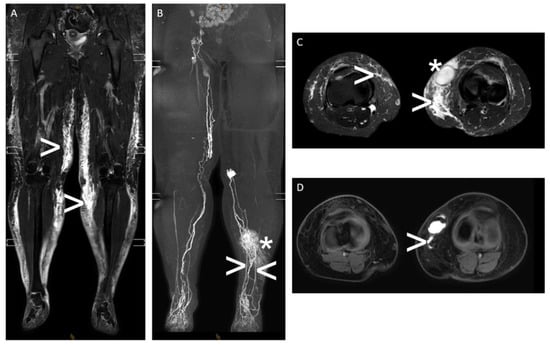

Figure 6.

“Interstitial MR lymphangiography“—A 43-year-old woman with massive lymphedema of both legs and a refractory superficial lymphocele medial to the left knee with an intermittent cutaneous lymphatic fistula after multiple plastic surgeries of the legs. Note: (A,C) T2-weighted, fluid-sensitive MRI ((A): coronal plane and (C): axial plane) showing subcutaneous lymphedema of both legs (white arrowhead) and the lymphocele of the left leg (white asterisk); (B,D) contrast material (gadolinium)-enhanced “interstitial MR lymphangiography” (B): coronal maximum-intensity projection and (D): axial plane showing impaired lymphatic run-off of both legs with dilated superficial lymph ducts, dermal reflux on the left (white asterisk), and active lymphatic fistula draining into the lymphocele on the left with two superficial lymphatic feeders (white arrowhead).

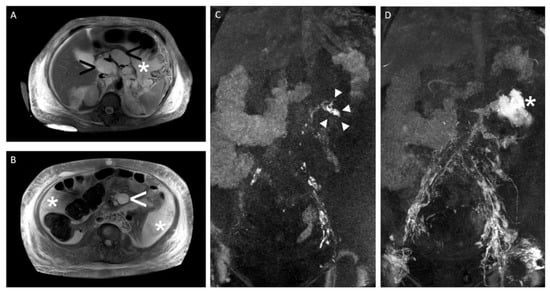

Figure 7.

“Intranodal MR lymphangiography“—A 59-year-old woman with massive refractory chylaskos (>5000 mL per day) after retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. Note: (A,B) T2-weighted, fluid-sensitive MRI (axial plane) showing ascites (white arrowhead), massive subcutaneous lymphedema (white asterisk), and multiple cystic/necrotic retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymph node metastases (black arrowhead); (C,D) dynamic contrast material (gadolinium)-enhanced “intranodal MR lymphangiography” (coronal maximum-intensity projection) showing the fistula point with pathologic contrast material extravasation from retroperitoneal lymph ducts on the left during contrast material’s injection (white arrowhead) (C) and massive contrast material extravasation into the ascites after contrast material’s injection (white asterisk) (D).

Ultimately, the choice of the appropriate form of lymphangiography depends on the type and location of the lymphatic fistula, the interdisciplinary treatment strategy employed, and the expertise of the center [2,4,5,7,11,12,13].

“Conventional lymphangiography” shows a technical success rate of 75–100% with a very low rate of major complications [1,3,4]. According to systematic reviews, direct or indirect radiologic fistula detection is successful in 58–95% of cases, with the additional use of CT associated with better results [1,3]. In addition, it is notable that “conventional lymphangiography” with an oil-containing contrast material has both diagnostic and therapeutic effects. Due to its high viscosity, there is a blockage of the feeders by the oil-containing contrast material, which, in many cases, can already lead to healing. Accordingly, cure rates of up to 70%—after single or repeat conventional lymphangiography—have been reported in the literature, with worse clinical outcomes for high-output fistulas [1,3,4,7]. In the most extensive paper on transpedal lymphangiography involving 355 patients, the Heidelberg University Hospital was able to define two positive predictors of healing: a drainage volume of <500 mL per day and a pathologic extravasation of the contrast material [4]. Therefore, “conventional lymphangiography” with an oil-containing contrast material is used as second-line therapy in different centers [1,2,3].

“MR lymphangiography” provides remarkable results as a purely diagnostic procedure. In patients with chylothorax, “interstitial MR lymphangiography” provides clinically useful information in 92% of patients, such as the identification of anatomic variants in 88% of patients. Procedure-related complications were not observed [9]. Compared with “interstitial MR lymphangiography”, “intranodal MR lymphangiography” is more complex to perform but provides better information regarding the dynamics of central lymphatic run-off [5]. For example, the correct identification of pathologic drainage in the upper abdomen can provide important information used to determine the further treatment strategy. Dynamic MR lymphangiography can detect retrograde lymphatic drainage from the cisterna chyli into the mesenteric lymphatics in chylaskos or antegrade collateral lymphatic drainage via the liver and diaphragm directly into the thoracic duct, bypassing the cisterna chyli in the chylothorax [14].

As described, lymphangiography is a technically reliable, safe, and effective procedure for the radiological imaging of the lymphatic system and fistulas. Our discipline now offers not only the possibility of detection and localization but also treatment. The image-guided percutaneous interventions for lymphatic fistulas, developed or optimized in recent years, are diverse. They may have several advantages over surgical and conservative procedures, including higher clinical success rates, lower procedure-related complication rates, and cost effectiveness. The standard procedures include CT-guided “interstitial embolization” for iliac lymphocele or chylaskos and fluoroscopy-guided antegrade or retrograde “thoracic duct embolization” for postoperative chylothorax or plastic bronchitis. More information regarding the armamentarium can be found in the literature, including the reviews “Back to the Future: Lipiodol in Lymphography-From Diagnostics to Theranostics” and “Radiological management of postoperative lymphorrhea” [2,3]. A brief overview is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Brief overview of image-guided percutaneous interventions for lymphatic fistulas.

The anticipated future increase in demand regarding medical services for the treatment of lymphatic pathology presents challenges for the field of radiology and its clinical partners. The standardization and broader implementation of radiological procedures, the implementation of generally accepted interdisciplinary treatment regimens, and, finally, the establishment of evidence-based guidelines are all urgently needed. One important step could have been realized on 19 March 2022 when the “1st Surgical-Radiological RoundTable for the Improvement of the Interdisciplinary Treatment of Patients with Postoperative Lymphatic Fistulas” took place in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Participants from different institutions discussed topics such as perspectives, levels of evidence, and action plans (ES. 1). In addition to the purely medical aspects, the health economic aspects were also discussed. For example, the significant reduction in the length of stay for patients with acute postoperative lymphatic fistulas after therapeutic lymphangiography could be an interesting strategic lever for case managers and controllers. More detailed information on these key performance indicators—with possible simultaneous improvements in economic and medical quality—can be found, for example, in two original papers by our group [4,14]. The initiative of this first RoundTable serves to consolidate and further develop a constructive interdisciplinary dialogue with the primary objective of improving the quality of patient care already established in the short term.

Video S1 “Intranodal lymphangiography“

Note: Following the ultrasound-guided positioning of a 23G spinal needle into the hilar region of an inguinal lymph node, this footage shows the fluoroscopy-guided injection of an oil-containing contrast material together with a visualization of the inguinal and iliac lymph ducts and lymph nodes.

Supplementary File S1 “1st Surgical-Radiological RoundTable for the Improvement of the Interdisciplinary Treatment of Patients with Postoperative Lymphatic Fistulas“—Agenda and preliminary results.

Note: Excerpt after editing some of the original data documented in the German language.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jvd2010003/s1, File S1: “1st Surgical-Radiological RoundTable for the Improvement of the Interdisciplinary Treatment of Patients with Postoperative Lymphatic Fistulas“—Agenda and preliminary results; Video S1: “Intranodal lymphangiography“.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.S. and C.C.P.; methodology, C.M.S. and C.C.P.; software, not applicable; validation, C.M.S. and C.C.P.; formal analysis, not applicable; investigation, C.M.S. and C.C.P.; resources, C.M.S. and C.C.P.; data curation, not applicable; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.S. and C.C.P.; writing—review and editing, C.M.S. and C.C.P.; visualization, C.M.S. and C.C.P.; supervision, not applicable.; project administration, not applicable; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the nature of a retrospective analysis of published data with no impact on therapy.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest with respect to this article.

References

- Sommer, C.M.; Pieper, C.C.; Itkin, M.; Nadolski, G.J.; Hur, S.; Kim, J.; Maleux, G.; Kauczor, H.U.; Richter, G.M. Conventional Lymphangiography (CL) in the Management of Postoperative Lymphatic Leakage (PLL): A Systematic Review. Rofo 2020, 192, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieper, C.C.; Hur, S.; Sommer, C.M.; Nadolski, G.; Maleux, G.; Kim, J.; Itkin, M. Back to the Future: Lipiodol in Lymphography-From Diagnostics to Theranostics. Invest Radiol. 2019, 54, 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, C.M.; Pieper, C.C.; Offensperger, F.; Pan, F.; Killguss, H.J.; Köninger, J.; Loos, M.; Hackert, T.; Wortmann, M.; Do, T.D.; et al. Radiological Management of Postoperative Lymphorrhea. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2021, 406, 945–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, F.; Richter, G.M.; Do, T.D.; Kauczor, H.-U.; Klotz, R.; Hackert, T.; Loos, M.; Sommer, C.M. Treatment of Postoperative Lymphatic Leakage Applying Transpedal Lymphangiography-Experience in 355 Consecutive Patients. Rofo 2022, 194, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieper, C.C. Nodal and Pedal MR Lymphangiography of the Central Lymphatic System: Techniques and Applications. Semin. Intervent. Radiol. 2020, 37, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardinet, T.; Veer, H.V.; Nafteux, P.; Depypere, L.; Coosemans, W.; Maleux, G. Intranodal Lymphangiography with High-Dose Ethiodized Oil Shows Efficient Results in Patients With Refractory, High-Output Postsurgical Chylothorax: A Retrospective Study. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 217, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, F.; Loos, M.; Do, T.D.; Richter, G.M.; Kauczor, H.U.; Hackert, T.; Sommer, C.M. The Roles of Iodized Oil-Based Lymphangiography and Post-Lymphangiographic Computed Tomography for Specific Lymphatic Intervention Planning in Patients with Postoperative Lymphatic Fistula: A Literature Review and Case Series. CVIR Endovasc. 2020, 3, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieper, C.C.; Schild, H.H. Interstitial Transpedal MR-Lymphangiography of Central Lymphatics Using a Standard MR Contrast Agent: Feasibility and Initial Results in Patients with Chylous Effusions. Rofo 2018, 190, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieper, C.C.; Feisst, A.; Schild, H.H. Contrast-Enhanced Interstitial Transpedal MR Lymphangiography for Thoracic Chylous Effusions. Radiology 2020, 295, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenpfeil, J.; Kupczyk, P.A.; Henkel, A.; Geiger, S.; Köster, T.; Luetkens, J.A.; Schild, H.H.; Attenberger, U.I.; Pieper, C.C. Ultrasound-Guided Needle Positioning for Nodal Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MR Lymphangiography. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, C.C.; Wagenpfeil, J.; Henkel, A.; Geiger, S.; Köster, T.; Hoss, K.; Luetkens, J.A.; Hart, C.; Attenberger, U.I.; Müller, A. MR Lymphangiography of Lymphatic Abnormalities in Children and Adults with Noonan Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vach, M.; Wagenpfeil, J.; Henkel, A.; Strieth, S.; Luetkens, J.A.; Ko, Y.-D.; Schild, H.H.; Attenberger, U.I.; Pieper, C.C. MR-Lymphangiography Identifies Lymphatic Pathologies in Patients with Idiopathic Recurrent Cervical Swelling. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2022, 7, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, F.; Loos, M.; Do, T.D.; Richter, G.M.; Kauczor, H.U.; Hackert, T.; Sommer, C.M. Percutaneous Afferent Lymphatic Vessel Sclerotherapy for Postoperative Lymphatic Leakage after Previous Ineffective Therapeutic Transpedal Lymphangiography. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2020, 4, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, R.; Kuner, C.; Pan, F.; Feißt, M.; Hinz, U.; Ramouz, A.; Klauss, M.; Chang, D.-H.; Do, T.D.; Probst, P.; et al. Therapeutic Lymphography for Persistent Chyle Leak after Pancreatic Surgery. HPB 2022, 24, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).