Abstract

The Seychelles blue bond is an innovative finance mechanism that has played a pivotal role in shaping the global landscape of blue bonds. Seychelles leadership in the blue economy sets a significant precedent. However, this precedent has also raised concerns among various stakeholders. This study evaluates of Seychelles’ sovereign blue bond, which was co-developed by the government of Seychelles and the World Bank. Three themes are explored, how the blue bond relates to other actors and donors in the blue economy space of Seychelles; how the blue bond contributes to advancing the national agenda and blue economy of Seychelles; and the key strengths, enablers and weaknesses of the blue bond. A series of considerations for future blue financing and blue bond mechanisms are presented, based on the findings of this study, to ensure that financing extends beyond blue washing and contributes meaningfully to the holistic transition to a sustainable blue economy. Our findings imply significant considerations for stakeholders in sustainable finance, suggesting ways to enhance the efficacy of blue bonds and emphasising the need for further research on their long-term impact and integration with other financial instruments.

1. Introduction

Blue finance is a growing area of interest that represents a way to address both the risks and opportunities associated with the blue economy (which includes aquatic and inland water sources as well as coasts and oceans) while pursuing sustainable development. The ocean economy is specifically estimated to be worth roughly USD 24 trillion globally and has been subjected to increasing attention since the conceptualisation of the blue economy post Rio +20 [1]. Despite the breadth and extent of economic activity in aquatic and marine environments, the combined pressures of climate change, pollution, and overexploitation threaten the health and sustainability of these environments, placing the blue economy at significant risk [2]. Evolving concurrently with the concept of the blue economy, which seeks to balance economic growth and sustainable development, blue financing offers opportunities to protect access to clean water, improve sewage in coastal cities, conserve underwater environments, and promote investment in a sustainable blue economy, including for various blue economy sectors and cross-cutting blue economy needs [3,4].

Public and private investment in a sustainable blue economy is still insufficient, which has led to a significant finance gap [5]. The World Economic Forum estimates that USD 175 billion of Blue Finance is required annually to achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14: Life Below Water by 2030. However, SDG 14 is currently the least funded of the 17 SDGs and has received just below USD 10 billion in total between 2015 and 2019 [6]. Financing a sustainable blue economy has the dual benefits of providing likely lucrative returns for investors whilst redirecting capital toward more sustainable approaches to economic development as opposed to historical, growth-at-all-costs methods. The financial sector is often overlooked in marine planning. Finance plays a pivotal role in advancing the blue economy, because funds are needed for investing in governance and initiatives to promote sustainable ocean use while reducing threats and mitigating the underlying drivers of ocean health decline [7]. Blue economy related sectors (such as water and wastewater management, reducing pollution, ecosystem restoration, sustainable shipping, tourism, or offshore renewable energy) have become increasingly attractive to investors, insurers, banks, and policymakers as a new source of opportunity, resources, and prosperity. Financial institutions are pivotal in providing the requisite financing, investment, and insurance to power these sectors [8]. In short, blue financing is defined as any “financial activity (including investment, insurance, banking and supporting intermediary activities) in, or in support of, the development of a sustainable blue economy, for example through the application of the Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles in financial decision-making, ESG frameworks, and reporting” [8].

Blue bonds and blue loans are the two most popular forms of blue financing, both of which exist as debt instruments. Both public and private sectors may gather capital for a sustainable blue economy through a number of blue financing instruments. The deployment of these instruments depends on the financial risks the capital providers are willing to accept, as well as on the expected returns from the investments. Blue bonds are instruments in which proceeds will be exclusively applied to new and existing blue projects that focus on aquatic and marine conservation or other environmental sustainability purposes. For example, blue bond funded projects can include conservation or research initiatives, or support the implementation of new technologies in fisheries. Blue bond funded projects should follow a specified process and set of eligibility criteria to be considered ‘blue’ (adapted from [9]). There is an increasing number of guidance issuances on what principles should accompany blue bonds, including those of the International Capital Market Association [10]. Blue bonds in particular have been increasingly adopted as a blue financing approach, modelling off of green bonds, with over 26 having been implemented globally as of early 2023 reaching over USD 5 billion [11]—despite the small USD 15 million of the Seychelles blue bond—by various financing institutions, and several more are currently being prepared [11]. Beyond debt issuances, other blue financing mechanisms include impact-only investment, blended finance (combining overseas development aid with private capital), social impact bonds or environmental impact bonds [12] and equity [13].

Blue finance is key for facilitating the implementation of the blue economy through multiple reinforcing avenues. Sustainable finance and investment to support the transition to a sustainable blue economy can be divided across three key areas. First, long-term finance to enable the implementation of laws and policies (both existing and emerging), particularly those related to integrated marine management, including regulation, enforcement, data management, monitoring and reporting. Second, investment in current and emerging ocean-based sectors to support sustainable economic diversification. Third, finance for the implementation of conservation and restoration of coastal and marine ecosystems.

Blue finance has a role to play in establishing strong and supportive enabling environments for the blue economy. The blue economy requires innovation, co-operation across diverse sectors, and innovative partnerships to generate the energy and momentum necessary to achieve sustainable development and economic growth [14]. Financial support can assist in fostering creative public-private partnerships, empowering local leaders, and supporting the creation of data and monitoring systems. For example, part of the blue bond in Seychelles has been used to fund high resolution 2D and 3D coastal mapping [15] to support strategic coastal zone decision making. Financial support can be used to strengthen the existing institutional framework to create a supportive environment for blue economy progress. Blue finance can also provide long term funding for policy generation and implementation through covering technical costs, and supporting the creation of legislation. Building a robust governance system, including transparent regulation and strategic direction, is imperative in sustaining implementation of the blue economy [16]. Blue finance can also support the creation of institutions to manage on the ground implementation. The role of the Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT) in Seychelles, created as a requirement of the country’s Debt for Nature Swap, has become a critical component of the country’s blue economy implementing infrastructure through continuous fund and awareness raising, publicity of blue economy projects, and nurturing and empowering local leaders.

By increasing availability of direct investment to emerging sectors, blue finance can support economic diversification by providing financial stability at crucial early stages. Supporting innovative and emerging sectors at such early stages can also increase social and environmental sustainability, when these conditions are mandated into financial assistance. For example, to receive funding, projects can be asked to address specific social issues such as youth participation or gender equity. In this way, niche or emerging sectors can be supported to address a range of sustainable development challenges, providing an additional layer of accountability. Investing early into nascent sectors can ensure that good practice is followed when developing emerging priority sectors, and builds resilience.

Seychelles Blue Finance Context

Seychelles is politically classified as a small island developing state (SIDS), and is an archipelagic nation in East Africa comprising 115 islands with 446 km2 of land mass and an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of approximately 1.35 million km2. As a self identified large ocean state, with an EEZ/land ratio of 2916.3:1 [17], the blue economy is critical to Seychelles GDP, with the economy reliant on tourism and fisheries (primarily industrial tuna) [18] which contributed 72% and 17% to GDP, respectively, in 2019. Seychelles has been an early pioneer and champion of the blue economy concept at a global stage, with the blue economy being a priority policy objective since 2015. It has achieved national integration and direction through various national policies, such as the National Development Strategy [19], Vision 2033 [20], the Blue Economy Roadmap (2018–2030) and the Blue Economy Action Plan [21]. The blue economy is coordinated by the Ministry of Fisheries and Blue Economy, under which the Department of the Blue Economy is designed to facilitate cross-sectoral collaboration for blue economy efforts. While Seychelles’ prosperity is directly linked to the health of its coastal and marine environments, graduating to a high-income country in 2015 meant that Seychelles was no longer eligible for ODA-based/concessional funding. This graduation, coupled with a very particular macro-economic agenda to reduce the country’s debt/GDP ratio, and further encouraged by International Monetary Fund (IMF) reforms, forced policymakers to find innovative forms of finance for national development [22]. With support from The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and the World Bank, the Debt for Nature Swap in 2015 [22,23,24] and blue bond in 2018 [25,26], respectively, have been applied as a means for Seychelles to achieve its macroeconomic aims, in line with the country’s national agenda to pioneer the blue economy approach.

Seychelles is regarded as a global frontrunner in blue finance and had the world’s first blue bond. However, the applicability and lessons learned from this financing approach are still nascent [3,26] partly due to relatively slow uptake and implementation, making it, until now, too early to clearly understand how it has supported operationalising the blue economy, and the wider macro-economic aims of Seychelles.

Using a qualitative approach based on interviews and field observations supported by long-term experience with working in Seychelles’ blue economy space, this paper aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the blue bond in supporting Seychelles to achieve a blue economy and its broader macroeconomic objectives. Following the methods described below, the blue financing landscape in Seychelles is presented to set the scene for the evaluation. The strengths and weaknesses of the blue bond approach are then presented, followed by a section which reflects on the lessons learned and suggestions for improving blue bonds as a finance approach, which will benefit Seychelles as well as other nations considering blue bonds.

2. Materials and Methods

To assess the bond’s impact, we used a qualitative research approach. This study is based on a full evaluative case study of the blue bond in Seychelles. This study employed qualitative research methods and is a case study evaluation consisting of semi-structured interviews, literature reviews, a thorough examination of the portfolio of support to Seychelles, and field observations of key sectors to allow for a triangulation of findings [27]. Semi-structured interviews were chosen to allow for free-flowing discussion to identify the limits and merits of blue financing initiatives of most relevance to the interviewee.

2.1. Sampling Strategy

Interviewees were identified through their involvement in blue financing, including the creation, delivery, and receipt of innovative blue financing mechanisms, especially those involved in the design and delivery of blue bonds, including those of Seychelles. This direct inclusion criterion ensured that the participants had firsthand experience and insights into the blue economy’s financing aspects. Additional interviewees were identified by recommendation of the first round of interviewees. This snowball sampling technique allowed for the inclusion of ‘outside’ perspectives of those who are involved in the broader blue economy of Seychelles but do not engage with blue financing (e.g., conservation NGOs). The inclusion criteria emphasised stakeholders’ relevance and contribution to the blue economy, while the exclusion criteria removed those without direct experience or influence on blue financing mechanisms in Seychelles. These perspectives were sought to provide a rich context and holistic understanding of the implications of blue financing on the ground [27]. In total, 24 interviews were undertaken which consisted of interviews with blue governance actors, financiers, researchers, recipients and non-governmental organisations. Due to the relatively small number of actors engaged with the Seychelles blue economy, no further identifying detail regarding interviewees is given to maintain anonymity and confidentiality.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

Prior to their participation, all interviewees were provided with detailed information about the study’s purpose, what their participation would involve, the intended use of the information collected, and their rights as participants. Written or verbal consent was obtained from each participant, ensuring they agreed to participate under informed conditions. The consent process also covered the confidentiality of their responses and their right to withdraw from the study at any point without penalty. To protect the participants’ privacy, all data were handled with strict confidentiality. Personal identifiers were removed from interview notes and observations, and any potentially identifying information was anonymised in the analysis and reporting stages.

The evaluation was designed to minimise any potential harm or discomfort to the participants. Interview questions were carefully designed to avoid sensitive topics that could cause distress. In instances where discussions touched upon sensitive issues, participants were reminded of their right to decline to answer specific questions or to end the interview at any time.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Interviews were conducted in person between August and October of 2023, five years after the issuance of the bond. Interviews were not recorded or transcribed at the request of the coordinating body of the evaluation. This approach also helped to elicit more open and elaborate responses from the interviewees, who might have otherwise inhibit their responses knowing that they were being recorded [28]. Extensive notes and observations were taken by the interviewer in a consistent manner according to the interview questions, and a series of thematic areas were discussed, including challenges, successes, structure, monetary concerns, unintended consequences, and conservation. Unique themes were also identified during the note-taking process in the interviews (in situ).

Data from the interviews were analysed using narrative and thematic analysis techniques [27]. This dual approach allowed for the identification of further overarching themes and patterns while also increasing our understanding of the individual stories and experiences of the participants. Importantly, all analyses were conducted manually, without the assistance of software or databases, to maintain a close, interpretative engagement with the data. Themes were derived directly from the data, ensuring that the findings were grounded in the participants’ perspectives and experiences. The findings were further explored through relevant studies in the literature and a series of follow-up conversations with the interviewees to clarify any points of confusion.

2.4. Limitations

The evaluation relied on qualitative data gathered through semi-structured interviews, literature reviews, and field observations. While these methods provide deep insights into the stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences, they are subject to the limitations typical of qualitative research, including potential biases in participant selection and the interpretive nature of data analysis.

This study’s findings are based on a targeted sample of stakeholders that are directly involved in, studying, or affected by the blue bond initiative. While efforts were made to include a diverse range of perspectives, the availability and willingness of stakeholders to participate could have introduced selection bias. Additionally, the relatively small sample size, given the niche field of blue economy financing, may limit the extent to which these findings can be generalised.

Given that the blue bond is a pioneering effort, with its issuance taking place relatively recently, the evaluation’s ability to assess long-term impacts is naturally limited. The evolving nature of blue economy initiatives and the time scales required to observe significant environmental and socio-economic outcomes mean that some effects of the blue bond may not be fully realised or measurable at the time of this study.

The decision to conduct narrative and thematic analyses manually, without the use of a database or specialised software, was driven by the study’s qualitative approach. While this allows for an in-depth engagement with the data, it may also limit the ability to systematically organise and cross-reference data points across a broader dataset, potentially affecting the thoroughness of the thematic analysis.

Lastly, while the focus on the blue bond provided detailed insights into its structure, implementation, and impacts, it also constrained the evaluation’s ability to compare and contrast other potential or existing blue financing mechanisms. This limitation narrows the scope of this study to the blue bond’s specific context and outcomes without a broader comparative analysis of alternative models.

3. Blue Financing in Seychelles

3.1. Debt Restructuring, the Swap and SeyCCAT

To discuss the blue bond in Seychelles, an understanding of the debt restructuring, debt for nature swap and SeyCCAT is necessary for context, but is presented herein with brevity as a high-level overview, as it is has already been well studied and documented [22,23,24].

One of the Government of Seychelles’ (GoS) debt-restructuring initiatives as part of its economic reform and liberalisation efforts was a Debt for Nature Swap, facilitated by TNC. This fist of its kind swap, focussed on ocean conservation, was designed to repurchase, restructure and ultimately relieve Seychelles of a portion of its debt held by the Paris Club, an informal group of 22 creditor countries. TNC mobilised funds from impact investors and grant capital to assist the GoS with the purchase of its debt. However, TNC was unable to loan these funds to a country’s government. Thus, SeyCCAT was set up in 2015 as a public–private trust to manage the proceeds of the debt swap independently. TNC then transferred USD 20.2 M to SeyCCAT; USD 15.2 M was used as a long-term loan, and USD 5 M was used as grant funding. SeyCCAT then loaned USD 20.2 M to the GoS to buy back sovereign debt from the Paris Club at a discounted rate. The Paris Club approved the repurchase of USD 21.6 M of GoS’s debt at a cost of USD 20.2 M, the value of the loan it received from SeyCCAT. This translated to a discount of 6.5 cents on the dollar, or a reduction of approximately USD 1.4 M, which is a modest reduction due to Seychelles displaying signals of economic strength through its budget surplus and firm growth at the time [23]. The debt received by the GoS was then split into two ‘promissory notes’: a USD 15.2 M note to be repaid to SeyCCAT over 10 years at 3% interest for repaying the TNC loan. The second note was for USD 6.4 M, comprising the USD 5 M grant from TNC and impact investors and the USD 1.4 M discount from the debt swap transaction, which was also paid to SeyCCAT at 3% over 20 years. The second note’s annual payments of USD 430 k were used for two purposes: USD 280 k was used for grant disbursement and the administrative costs of the Trust, and USD 150 k was used to capitalise an endowment over a period of 20 years at an anticipated 7% return, yielding an expected value of USD 6.6 M [23]. A primary term of the debt swap was for Seychelles to embark on a Marine Spatial Planning process which would guide the process of expanding the country’s marine protected areas from ~1% to >30% of its EEZ [22].

SeyCCAT’s existence is a direct result of the debt swap due to TNC not being able to loan funds to the GoS itself. SeyCCAT’s independent trust status and its successful track record of managing funds contributed to it being awarded USD 3 M from Seychelles’ blue bond to disburse to grant applicants. Thus, at the time of writing, SeyCCAT disburses up to USD 700 k in grants per year, known as the ‘blue grants fund’ (BGF), with USD 200 k being from the debt swap, paid over 20 years, and USD 500 k being from the blue bond, paid over a period of 6 years. The grants are allocated annually in a competitive manner to Seychellois-led projects aligning with one of SeyCCAT’s five strategic objectives, with small- (~USD 7400) medium- (~USD 74,000) and large (~USD 148,100)-sized grants available. It also allocates ~USD 11,100 as a Blue Business Grant annually. These grants primarily fund marine conservation, blue economy, climate adaptation programmes and the Seychelles Marine Spatial Planning initiative (SMSP). Through the BGF and several other long term projects, SeyCCAT, which is co-chaired by the TNC and GoS, plays a key role in facilitating Seychelles’ conservation efforts [25].

Based on the ability of Seychelles to direct capital into its Blue Economy, the potential for debt swaps for SIDS and other states with large ocean resources is often highlighted. However, theSeychelles debt swap as a blueprint may not be universally applicable. The success of this model is linked to Seychelles’ conservation legacy and deeply entwined with Seychelles’ pre-existing economic reforms overseen by the IMF which had already led to a steady decrease in debt. Additionally, from a governance standpoint, the creation of the public-private, independent trust, SeyCCAT, was critical for the impartial management of funds as opposed to having a governmental entity, thus providing external investors with increased confidence [16]. Without this reform and governance avenue, the swap might not have been successfully negotiated.

Critics underscore potential limitations, including the undervaluation of ecosystems and services protected by the Seychelles swap and the extent of decision-making influence allocated to TNC in SeyCCAT’s governance structure [24].

3.2. Blue Bond Structure and Setup

Seychelles issued the first sovereign blue bond in 2018, facilitated by the World Bank, which defines blue bonds. as “a debt instrument issued by governments, development banks, or others to raise capital from impact investors to finance marine and ocean-based projects that have positive environmental, economic, and climate benefits” [29]. Proceeds from the bond also contribute to the third South West Indian Ocean Fisheries Governance and Shared Growth Project (SWIOFish3), which supports Seychelles in sustainably managing their fisheries and increases economic benefits from their fisheries sectors.

The bond was supported by a diverse actor network. A business case was identified with support from Prince of Wales’ Charities International Sustainability Unit. A multidisciplinary World Bank team assisted with structuring the bond, Standard Chartered acted as placement agent for the bond and Latham & Watkins LLP advised the World Bank as external counsel. Clifford Chance LLP acted as transaction counsel [22].

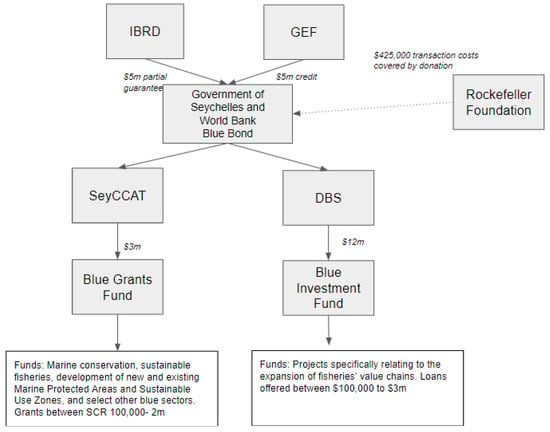

The bond is partially guaranteed by IBRD for USD 5 million, and supported by a concessional loan from the Global Environment Facility of USD 5 million to cover partial interest payments. The Rockefeller Foundation donated USD 425,000 to cover transaction costs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of the Seychelles blue bond. Authors’ conception.

The bonds are managed by SeyCCAT and the Development Bank of Seychelles (DBS). USD 3 million of the blue bonds is used as a contribution to SeyCCAT’s BGF, supplementing the grant funding allocated from the debt swap. The BGF supports marine conservation, fisheries, MPA development, and other blue economy sectors through grants of up to SCR 2 million (~USD 148,000). As of the sixth round of funding in 2022, 69 projects have been funded (T Manjengwa, personal communication, 8 September 2023), with projects ranging from monitoring the movement of giant trevally in Seychelles’ outer islands, exploring MPA size suitability for the protection of juvenile sickle-fin lemon shark, conducting a baseline marine biodiversity assessment around Frégate Island, exploring the feasibility of rock oyster and seaweed farming, and supporting Entrepreneurship Development in the blue economy with the partnership of the Enterprise Seychelles Agency [25].

DBS manages USD 12 million of the bonds through the Blue Investment Fund, which supports the expansion of sustainable fisheries’ value chains in Seychelles, including aquaculture, cold storage, food processing, research and scientific and logistics. Loans range from USD 10 k to USD 3 million by DBS at a 4% interest rate, repayable over 15 years with a 10% down payment required. To date, one applicant has been awarded a loan of USD 3 million to develop fishery processing systems. This applicant is already a well-established business owner in the fisheries industry.

4. Results and Discussion

The results of the stakeholder interviews are presented in this section, accompanied by contextualisation from the literature review. Three themes are explored, how the blue bond by the World Bank relates to other actors and donors in the blue economy space of Seychelles; how the blue bond contributes to advancing the national agenda and blue economy of Seychelles; and the key strengths and weaknesses of the blue bond.

4.1. Relationship of the Bond to Other Actors and Donors

The primary finding regarding the actors in the blue finance space of the Seychelles is that donors and financiers, including the Bank, are not engaging with each other in a way that truly supports a holistic transition to a sustainable blue economy. One interviewee highlighted that “there have been opportunities for donors such as the EU, the Bank, TNC, and others to come together, but they have not been doing the work to coordinate their objectives and interventions for support”. Another interviewee noted that “all donors are trying to do their own thing, without thinking of the load this puts on the GoS. There is also no body within GoS that sufficiently coordinates with all the donors to identify how their support overlaps or conflicts, and donors should be cognisant of this”. This fragmented approach, by extension, might not be entirely conducive to establishing the necessary conditions for a holistic and sustainable transition towards a blue economy in the context of Seychelles, aligned with the national vision, as opposed to being a donor driven agenda.

Regarding other financing mechanisms for marine activity in Seychelles, the Blue Investment Fund of the blue bond is in direct competition with the EU funded Fisheries Development Fund (FDF), also disbursed by the Development Bank of Seychelles. The FDF offers smaller loans with better returns and collateral for fishers, and with no environmental or social safeguards in comparison to BIF which often requires external support to apply for. In 2020, the GoS signed a six-year partnership with the EU, with an EU financial contribution of EUR 5.3 million per year, out of which EUR 2.8 million is earmarked for the support of the fisheries policy of Seychelles. To date, EU funding in fisheries has supported the development of fisheries facilities at la Retraite, landing sites and fish markets, and the aquaculture broodstock facility in Providence [30]. In essence, the BIF is being out-competed by the FDF at present, with two loans approved in 2021 at a value of SCR 4 m [31], compared to a single loan under BIF of USD 3 million.

In the context of financing the blue economy, the blue bond has limited influence in filling the financing gap for poverty alleviation and social justice. When looking at the way in which the World Bank is engaging in the blue financing dialogue in Seychelles (this excludes project activity such as that of SWIOFish 2 and 3 and refers only to bond), it is evident that there are already other ongoing initiatives to support fisheries, and there is a considerable volume of financing for conservation and climate change adaptation both through TNC’s Debt for Nature Swap and the various ongoing activities for conservation by the GoS and local NGOs. Interviewees generally express a feeling that the blue bond has been disconnected from other activities in Seychelles, as demonstrated by one interviewee who noted that “it is necessary to ensure that the money invested through the Swap is balanced with social and economic needs at the same time, especially where poverty alleviation and social justice aren’t currently covered by TNC”. Another interviewee stated that the bond “should have been designed to work better with other actors and existing activity to ensure that social elements of the blue economy are properly considered”. Given the saturation in this space, and the gaps that exist for financing other avenues for blue economy diversification, the blue bond has had limited influence on ensuring a balanced allocation of resources, and reinforcing socio-economic support for vulnerable coastal communities. As such, the setting up of the bond has not effectively harnessed the strengths of the coordinating institution to promote prosperity, supplementing existing blue economy initiatives. Notably, stakeholders have indicated that had such an approach been taken, it could harmonise with Seychelles’ ambitious climate targets and ongoing efforts to quantify its blue carbon [32] as well as other ecosystem services [33]. This alignment primarily involves fostering a blue carbon market, aligning with the principles outlined in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. It is worth noting that the IMF is already involved in financing activities related to blue carbon.

4.2. The Role of the Blue Bond in Advancing Seychelles’ Blue Economy

The blue bond, as a nascent financing mechanism, has done well in generating research and development through the BGF for diversification in line with the Seychelles country partnership framework (CPF), a diagnostic tool co-developed with the World Bank with the input of GoS. One of the primary focus areas of the CPF is sustainable growth for shared prosperity, identifying opportunities in fisheries and tourism and strengthening the management and resilience of natural endowments as priority objectives. This focus is aligned with the blue economy approach of Seychelles and its guiding blue economy roadmap. As such, the BGF component of the blue bond has been highly successful at funding projects which support diversification such as seaweed cultivation, oyster farming and pollution abatement while continuing to provide access to finance for non-commercial activities related to conservation and science. One interviewee mentioned that to them, “the projects funded under the BGF are the only part of the whole blue bond that really speak to a proper blue economy”, and that “these are the areas that donors and the GoS should be prioritising for ocean finance”. The research and developments in piloting these projects contributes significantly to understanding and the potential for new activities within the coastal and marine zones.

While the BGF supports innovative approaches, the BIF (which holds a much larger financial majority) and loan agreement terms perpetuate fisheries dependence and do little to change the perception that the blue economy exists only for fisheries in Seychelles. As stated in the BIF promotion brochure, “the Blue Investment Fund is a loan facility that offers affordable long-term financing to businesses that participate in the value chain of sustainable fisheries and help build commercial infrastructure for the fisheries sector in Seychelles”. As such, the BIF allocates all loan resources to fisheries value chain development, and as one interviewee stated, this is “possibly at the expense of other potential avenues for sustainable development within the blue economy approach”. This allocation strategy, if not suitably diversified, could inadvertently contribute to the perpetuation of Seychelles’ economic reliance on fisheries as the primary driver of its blue economy, potentially hindering the broader diversification efforts that are often considered crucial for a more resilient and sustainable economic landscape. However, according to the SWIOFish3 project and the blue bond terms, if the GoS chooses to support different areas of the blue economy such as marine renewable energy or eco-tourism, the terms would need to be renotiated with the investors. Stakeholders interviewed identified that high negotiation costs have prevented this to date. This is further evidenced by other research [34]. As such, despite being indebted, the GoS is unable to redirect financial resources for adaptation in response to local needs or changing contexts.

Further regarding the split of the bond, with only USD 3 m of the funding being used for research and development beyond fisheries, and the majority (USD 12 m) invested in fisheries and aquaculture, the funding arrangement also reinforces the notion that the blue economy in Seychelles is primarily about fisheries. When considered in the context of the EU fisheries financing, the level of investment in Seychellois fisheries by other donors could be reconsidered. There is significant potential for the Bank to intervene beyond fisheries and instead promote research, development and investment into emerging sectors.

The blue bond, in its current form, may not be optimally supporting the enabling environment for progressing the blue economy. Notably, it appears that the bond is not effectively addressing the key impediments that hinder progress in the blue economy. The challenge in implementing the blue economy is two-fold. Firstly, there is a limited integration of the blue economy concept across economic sectors. The tourism and fisheries industries, which collectively contribute significantly to the GDP, continue to operate in isolation. This isolation is due in part to the absence of a shared understanding of the benefits of collaboration among industry stakeholders and the dearth of initiatives that generate synergies across sectors. Secondly, the blue economy faces hurdles in influencing sector-specific policies and management measures. The rules governing the blue economy do not hold precedence over sector-specific regulations, resulting in a limited capacity for the Department of the Blue Economy (DBE). In light of these challenges, for the blue bond to genuinely align with the principles of the blue economy and effectively support its development, it should aim at promoting cross-sectoral integration, bolstering institutional capacity and infrastructure, and facilitating a holistic approach to marine management tools. Such an approach would involve bridging the existing gaps between the key economic sectors, aligning their interests, and harmonising policies to create a more synergistic and comprehensive framework for the blue economy.

4.3. Strengths and Weaknesses of Seychelles Blue Bond

Blue bonds are the latest innovation in increasing financial resources to be channelled to the blue economy, and the World Bank has played a pivotal role in spearheading this approach in Seychelles as a global pioneer. The blue bonds in Seychelles achieved the simultaneous goals of stabilising credit ratings, promoting further investment into the economy [26], and supporting a conservation agenda. This should be commended. A number of other countries have since implemented blue bonds, including Fiji’s inaugural sovereign blue bond, along with Indonesia; Belize; and many others [11]. Despite the small size of blue bonds, they are clearly increasingly being adopted and are expected to grow in popularity in line with green bonds, which reached over USD 1 trillion in issuances in 2020, just 13 years since the first issuance [26].

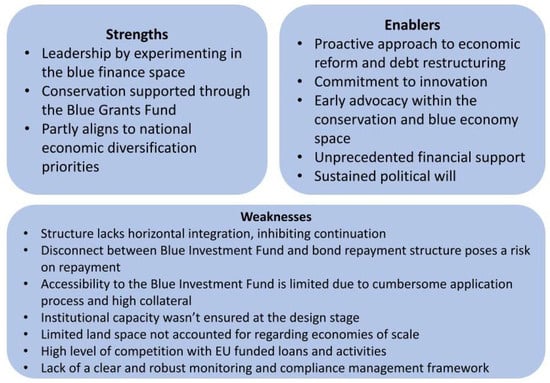

However, there are a number of lessons learned from applying this approach in Seychelles that should be taken on board for future financing associated with the blue economy. The key strengths, enablers and weaknesses of the Seychelles blue bond, as identified in this study, are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Summary of strengths, enablers and weaknesses of the seychelles blue bond.

In terms of strengths, the Seychelles blue bond has seen a number of successes, primarily around bringing blue financing to the forefront of the global agenda, supporting conservation activity, and diversifying an existing sector of the blue economy. This experimentation deserves recognition for bringing the concept of blue finance to the forefront, significantly enhancing global awareness of the blue economy. There is, as a result of the blue bond, an increasing recognition of the role oceans and seas play in climate change mitigation and adaptation. SeyCCAT has emerged as a pivotal figure in blue economy leadership, providing a structural model that can be emulated in future implementations, although SeyCCAT’s success has been the product of collaborative financing from both TNC and the Bank. An additional strength is the BGF’s local management and granting process, which ensures that decisions are made with an understanding of local needs and context, as highlighted by one interviewee who stated that “SeyCCAT as a body has the most practical understanding of the marine development needs of Seychelles, and as a result is in a good position to determine which projects are awarded grants to make sure that no perverse initiatives are funded”. Lastly, the bond has spurred positive research and development efforts in areas such as aquaculture research and development, feasibility studies for sustainable seafood, and pollution abatement, contributing to diversification within the landscape of an existing blue economy sector, namely fisheries. SeyCCAT’s achievements, facilitated in part by the Seychelles blue bond, serve as a compelling success story in the realm of blue economy development.

There are a number of enabling factors which provided the right environment for the blue bond to be established in a globally meaningful way, without which, half of the stakeholders interviewed expected it would have been a failure. First, the blue bond was driven by the country’s proactive approach to economic reform and debt restructuring, its commitment to innovation, early advocacy within the blue economy sector, unprecedented financial support, and sustained political will, all of which collectively enabled the blue bond to have a degree of relative success. Notably, since 2008, Seychelles has been undertaking extensive economic reform with support from international donors and agencies. Discussions about the Debt for Nature Swap began in 2011 [16], and the fact that, as highlighted by an interviewee, “Seychelles was willing to restructure their economy and debt set the political and domestic scene for the blue bonds programme to take advantage of the newly created blue financing environment”. Furthermore, Seychelles had been an early advocate and leader within the global blue economy landscape, attracting significant attention and support on both the domestic and international fronts. Seychelles has always had a strong conservation legacy in terms of protecting endangered species, and islands such as Cousin Island and the Aldabra Islands [35,36]. As identified by one interviewee, this basis also served as a “key part for the foundation of the blue economy to be initiated”. As such, the blue bond received unprecedented financial support for the set up of a new financing mechanism, with large donations (such as the half million by the Rockefeller foundation) to cover transactional costs [25]. Without these collective factors, it may have been significantly more challenging to set up such a globally recognised blue bond.

The weaknesses of the bond present a number of challenges. First, the design of the bond presents difficulties in the delivery and futureproofing of the bond and associated activities, due to a risk of being unable to pay back the loans [37] and a lack of horizontal integration between DBS and SeyCCAT. A primary concern arises from the risk associated with the bond’s repayment structure, as it is considered a government obligation disconnected from the BIF. While the BIF is designed as a revolving fund, its efficacy hinges on the ability to repay loans, which poses a significant financial risk that could jeopardise future projects. The structure of the payments detaches the outcomes of projects from the principal payments [38] rather than from the revenue of projects [39].

From a coordination perspective, the gap issue exists in the coordination between the SeyCCAT and DBS, resulting in a lack of horizontal integration. This sentiment was highlighted by a number of interviewees, where one indicated that “there has been no horizontal thinking in the setup of this bond scheme. The starting point between disbursements from DBS and Seyccat should not be aligned, because timelines clash. They wanted the funding allocation from SeyCCAT to be the leverage to apply for a loan with DBS. DBS should have been delayed by two years to allow for grants [from the BGF] to be completed and then apply for a loan [from the BIF]. This is a major flaw in the design of the bond”. This deficiency inhibits the seamless transition from receiving grants to applying for loans, impeding the effective use of available resources. Additionally, the bond has faced teething problems, marked by a dearth of initial traction and a limited pipeline of identified projects, ultimately resulting in low initial uptake. These challenges highlight the importance of addressing design issues to ensure the bond’s long-term viability and effectiveness.

Second, the design of the BIF exhibits a pronounced bias towards existing established businesses, favouring those with the capacity to navigate the intricate application process and meet the bond’s rigorous requirements. To access the loan, applicants require a substantial 10% down payment in conjunction with a high 1:1.25 collateral rate (as indicated in the BIF loan application manual), which presents a formidable barrier to accessing larger loans, raising questions about its benefit to anyone other than well-established enterprises. The application and requirements for the loan application is also a cumbersome process, where satisfying the bond’s prerequisites is a challenge for many, especially smaller-scale artisanal fishers or start-up business participants. This is demonstrated by a statement from one interviewee who said that “if there are those with doctorats who are complaining about the difficulties of filling the application, how would you expect a local fisher to do this?”. Another stakeholder identified that “the process to apply is making it super difficult to access funding, which then becomes really difficult for SeyCCAT as the one disbursing the fund. There are different requirements for everyone, which makes it all incredibly complicated”. Consequently, the bond’s accessibility is limited, compelling fishers to opt for more straightforward loans from the DBS, which do not impose such stringent sustainability criteria. As a result, the loans from the BIF appear somewhat redundant, exemplified by the fact that only a single loan has been granted since the inception of the bond. This disparity in accessibility and favouring of established entities raises questions about the bond’s intended beneficiaries and the extent to which it genuinely supports emerging industry, leaving artisanal individuals and smaller businesses notably disadvantaged in their ability to harness its potential benefits.

Third, there are a number of structural realities, such as the institutional capacity, the role of the EU in driving the national economy in Seychelles, and limited land space, that the design of the bond does not account for. The EU stands as a major trade partner for Seychelles, providing essential market access and crucial financial support for the nation’s fisheries sector [40]. This deep-rooted dependence on EU markets and support represents a structural reality that necessitates thoughtful consideration in the bond’s design, especially as interviewees identified that the former principal secretary to the Blue Economy department now serves as Seychelles Ambassador to the EU, further emphasising the EU’s role in Seychelles’ economic framework. Additionally, the bond’s implementation has presented a substantial undertaking for the DBS, where, according to one stakeholder, “the technical systems were simply not in place or sufficient in the DBS when the bond was started”. As such, the bond has “been a very heavy lift for DBS”, drawing a significant amount of resources to begin before any returns or management fees could be drawn by them. The initial focus on promoting the bond’s concept may have detracted from concurrent efforts needed to establish the requisite institutional setup and capacity, which are integral to the bond’s success. Interviewees identified that these structural issues, which would have allowed for a more efficient allocation of the bond’s resources, were not adequately addressed prior to the fund’s initiation. Moreover, the bond places considerable reliance on access to land for diversifying fisheries and aquaculture activities, yet land availability is scarce in Seychelles. The bond’s requirement for applicants to have access to land is not aligned with this structural reality, which hinders its accessibility and effectiveness.

Fourth, there is a lack of clarity regarding a robust monitoring and compliance framework, which is essential for ensuring that the bond remains aligned with blue economy objectives and sustainability principles. There is ambiguity regarding compliance post-loan award, with no clearly established regulations or mechanisms to oversee business operations after a loan is granted, and no interviewees could provide any information on how this would be managed. The current expectation primarily centres on loan repayment to DBS. However, there is uncertainty about who would be responsible for monitoring and enforcing compliance, especially with the impending completion of SWIOFish. This lack of a comprehensive compliance framework ultimately leaves much to be desired in terms of ensuring that the blue bond’s sustainability criteria are upheld. There is currently no mechanism in place to ensure compliance with the bond’s sustainability standards beyond simply abiding by national laws, which may not fully encapsulate the bond’s stringent environmental and social criteria. Additionally, based on a review of the SWIOFish3 Mid-term Evaluation, the monitoring of success by SWIOFish, SeyCCAT and DBS predominantly focus on the disbursement of funds rather than assessing the impact of these investments. This limited scope of monitoring provides an incomplete picture of the bond’s effectiveness in promoting the blue economy and sustainability. To address these challenges, a more robust monitoring and compliance management framework is imperative to ensure that the Seychelles blue bond continues to meet its sustainability and blue economy goals effectively.

5. Future Considerations for Blue Bonds

The novelty of the Seychelles blue bond, as the world’s first sovereign blue bond is commendable, and has been defining the blue bonds landscape on the global stage, by token of its being the world’s blue economy leader. However, a number of actors are concerned by the precedent that is being set, as indicated by the interviews in this study. Future blue financing and blue bond mechanisms could consider the following to ensure that financing extends beyond blue washing and contributes meaningfully to the holistic transition to a sustainable blue economy:

For future blue bond design with this type of split structure (the BIF and BGF), horizontal integration should be prioritised, and effective time structuring mechanisms introduced. Identifying and addressing existing gaps in the process is crucial, and the use of an incubator model can be instrumental in bridging these gaps. Specifically, the bond should be structured with a time delay between the disbursement of BFG grants, which typically support research and development projects, and the allocation of loans from the BIF. This temporal buffer would allow grantees the opportunity to complete their research and development initiatives before applying for loans to scale up their projects. Furthermore, establishing a strong linkage between the BGF and BIF would ensure that the grant scheme serves as an incubator for the loans, aligning the criteria and categories of the two with the overarching objectives of the blue economy. As highlighted by one stakeholder “they [the designers of the bond] have to either lower the expectations of the BIF, or create an interim accompaniment to fill the gap”. As such, there is scope for introducing blue incubator spaces. Initiatives such as The World Economic Forum and the Commonwealth Secretariat are already adopting blue incubators with their 1000 Ocean Startups and Blue Charter Project Incubator, respectively [41,42], and their lessons learned could be leveraged. Blue incubators, particularly with regional and international cooperation, related to other islands in the region, coupled with more emphasis on research and development at the early stage would help address the capacity gap and ensure that projects supported by the BGF are sufficiently equipped to meet the requirements of the BIF.

Blue bonds should extend beyond one sector to truly embody the blue economy approach, and ensure financial inclusivity. Using the Seychelles blue bond as an example, an opportunity exists to recalibrate the BIF’s investment strategy to encompass a more comprehensive range of blue economy sectors, thereby dispelling the notion that fisheries are the sole domain of the blue economy in Seychelles. By broadening the scope of the BIF to encompass multiple facets of the blue economy, including eco-tourism, biotechnology, education and awareness, and blue energy, the perception that the blue economy is synonymous with fisheries can be gradually reshaped. This shift in focus could foster a more balanced and inclusive approach to the development of the blue economy, aligning Seychelles’ objectives with a more diverse and sustainable vision for its blue economic future. Furthermore, future blue bonds’ accessibility should be tailored to various sectors and regions within the country to ensure that it reaches marginalised or underserved communities in line with the social equity and prosperity elements of the blue economy.

To further promote equitable access, blue bonds should incorporate mechanisms that specifically address the needs and capacities of various stakeholders, including small-scale entrepreneurs and local communities. This could involve simplifying the application process, offering training and support for potential applicants, and creating smaller, more accessible funding tiers. Additionally, criteria for bond access should be explicitly designed to be inclusive, ensuring that projects from a diverse range of applicants, particularly those from underrepresented or marginalised groups, are considered. As stated by an interviewee, “donors who are more flexible make much more impact, too much paperwork limits time to actually implement. With less focus on the process and more building of capacity for delivery, these types of bonds could have far more wide-reaching impacts for the marine environment and its communities”.

To fill the large financing gap that exists for implementation, compliance and management of the marine areas, it is necessary to balance multiple areas of donor support (such as the EU, TNC, and others in Seychelles) and leverage existing financial resources and mechanisms (such as other DBS loans and schemes in Seychelles). As stated by a stakeholder “GoS is constantly trying to balance multiple areas of donor support. They are a bit guilty that they grab at any finance available, which is understandable, but they end up spreading themselves too thin. This creates a lot of noise and competing interest about who is funding what, and donors should be more aware and considerate of this”. Balancing these multiple donor areas, and leveraging existing finance could involve creating a centralised platform for information and resource sharing, enabling better alignment of projects funded by different sources. Partnerships and joint funding schemes should be encouraged to maximise resource use and distribution.

In the context of small island, large ocean states, blue bonds should consider addressing land scarcity and environmental sustainability. Given the limited land availability, blue bonds should incorporate specific clauses or conditions that incentivise sustainable land use. This will ensure that the limited land available is used effectively, promoting ecological balance and sustainability. Projects funded by blue bonds could include innovative marine-based solutions that require minimal land usage, such as offshore aquaculture or renewable ocean energy.

Lastly, blue financing should ensure that the most appropriate financing mechanism is applied. The key metric of success for the blue bond should be its capacity to deliver transformative and sustainable impact, rather than solely focusing on investment and growth. Therefore, the measure of success should revolve around a set of guiding principles that steer the bond’s actions towards achieving meaningful diversification and enhancement of coastal and maritime activities. If expanding investment and growth is the key metric, then other financial mechanisms would be more suitable.

6. Conclusions

This study offers a comprehensive analysis of the Seychelles blue bond programme, underscoring the potential of blue bonds in supporting sustainable blue economy development if their structural design is improved, particularly in small island, large ocean states. Through a qualitative analysis grounded in semi-structured interviews, a literature review, and field observations, several key findings have emerged, offering valuable lessons for stakeholders in sustainable finance and policymaking. The findings identify the strengths, enablers, and weaknesses of the Seychelles’ blue bond, and a series of recommendations intended to help refine the approach towards blue bonds is presented.

Firstly, the Seychelles’ blue bonds have played a leading role in the global landscape of sustainable finance, demonstrating the potential of blue bonds to mobilise capital towards aquatic and marine-based sustainability projects. However, the evaluation has also highlighted critical areas for improvement, particularly in terms of enhancing the inclusivity and accessibility of such financial instruments to a broader range of stakeholders within the blue economy.

The findings underscore the importance of designing blue financing mechanisms that are flexible, inclusive, and tailored to the unique needs and capacities of different stakeholders, from established enterprises to small-scale entrepreneurs and local communities. Moreover, they emphasise the need for a more integrated and holistic approach to finance the blue economy, one that transcends sectoral boundaries and promotes cross-sectoral collaboration and innovation.

These findings further suggest a need to refine the design and implementation of blue bonds and other blue financing instruments. This involves incorporating more robust mechanisms for monitoring, compliance, and impact assessment. The Seychelles blue bond experience also highlights the critical roles of governance, institutional capacity, and stakeholder engagement in the success of blue economy financing. As such, future initiatives should prioritise the development of strong institutional frameworks, transparent and participatory governance processes, and mechanisms for stakeholder engagement and capacity building. Furthermore, future design considerations such as establishing strong horizontal institutional linkages and time-based mechanisms for project continuity (such as project incubators), balancing multiple areas of donor support, and leveraging existing financial resources would help to prevent blue washing and ensure meaningful contributions are made to the national agendas of developing the blue economy in line with blue economy principles.

These findings are useful to financial stakeholders who aid in the setup and funding of blue bonds, policymakers, blue finance researchers, and other stakeholders with a vested interest in blue financing, providing insights into leveraging blue bonds for environmental and economic benefits. As the global community continues to grapple with the challenges of sustainable development in the blue economy, particularly in the face of climate change and environmental degradation, the lessons learned from the Seychelles’ blue bonds provide a valuable point of reference.

Lastly, the findings of this evaluation suggest the need for further research on effective integration with other financial mechanisms and the long-term impacts of blue bonds on marine ecosystems and local economies.

Author Contributions

Conception A.M.; data collection A.M. and T.E.; analysis A.M., T.E., S.L. and J.R.; synthesis A.M., T.E., S.L. and J.R.; writing A.M., T.E., S.L. and J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all interviewees involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the confidential nature of this evaluation, data or transcripts from interviews are not available for public access.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the interviewees for providing their insights, experiences and time.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors wish to declare their involvements that are relevant to this study. The first author was a consultant on a wider blue economy evaluation upon which this study was based. One of the authors sits as a member of the SeyCCAT Finance Committee. The authors affirm that these roles have not influenced the content of this work in any way that presents a conflict of interest.

References

- OECD. The Ocean Economy in 2030; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.C.; Voyer, M.; Benzaken, D.; Watanabe, A. Blue Economy and Blue Finance: Toward Sustainable Development and Ocean Governance; Morgan, P.J., Huang, M., Voyer, M., Benzaken, D., Watanabe, A., Eds.; Asian Development Bank: Tokyo, Japan, 2023; ISBN 9784899742524. [Google Scholar]

- March, A.; Failler, P.; Bennett, M. Challenges when designing blue bond financing for Small Island Developing States. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2023, 80, 2244–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirumala, R.D.; Tiwari, P. Innovative financing mechanism for blue economy projects. Mar. Policy 2022, 139, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, D.F.; Vestvik, R.A. The cost of saving our ocean–estimating the funding gap of sustainable development goal 14. Mar. Policy 2020, 112, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Friends of Ocean Action. SDG14 Financing Landscape Scan: Tracking Funds to Realize Sustainable Outcomes for the Ocean [White Paper]. 2022. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Tracking_Investment_in_and_Progress_Toward_SDG14.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Shiiba, N.; Wu, H.H.; Huang, M.C.; Tanaka, H. How blue financing can sustain ocean conservation and development: A proposed conceptual framework for blue financing mechanism. Mar. Policy 2022, 139, 104575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEPFi. Rising Tide: Mapping Ocean Finance for a New Decade; Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Deschryver, P.; de Mariz, F. What Future for the Green Bond Market? How Can Policymakers, Companies, and Investors Unlock the Potential of the Green Bond Market? J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICMA. Bonds to Finance the Sustainable Blue Economy: A Practitioner’s Guide; International Capital Market Association: Zürich, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bosmans, P.; de Mariz, F. The Blue Bond Market: A Catalyst for Ocean and Water Financing. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2023, 16, 184. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1911-8074/16/3/184 (accessed on 25 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- de Mariz, F.; Savoia, J. Financial Innovation with a Social Purpose: The Growth of Social Impact Bonds. September 2018. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3306818 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Sumaila, U.R.; Walsh, M.; Hoareau, K.; Cox, A.; Teh, L.; Abdallah, P.; Akpalu, W.; Anna, Z.; Benzaken, D.; Crona, B.; et al. Financing a sustainable ocean economy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNDESA. Promotion and Strengthening of Sustainable Ocean-Based Economies. 2021. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/2014248-DESA-Oceans_Sustainable_final-WEB.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- SeyCCAT. High-Resolution 2D/3D Coastal Mapping on the Island of Mahé. The Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust. Available online: https://seyccat.org/high-resolution-2d-3d-coastal-mapping-and-monitoring-using-unmanned-aerial-vehicle-and-structure-from-motion-photogrammetry-techniques-on-the-island-of-mahe/ (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Benzaken, D.; Voyer, M.; Pouponneau, A.; Hanich, Q. Good governance for sustainable blue economy in small islands: Lessons learned from the Seychelles experience. Front. Political Sci. 2022, 4, 1040318. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.1040318 (accessed on 2 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hume, A.; Leape, J.; Oleson, K.L.; Polk, E.; Chand, K.; Dunbar, R. Towards an ocean-based large ocean states country classification. Mar. Policy 2021, 134, 104766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, S. Socio-Economic Assessment of the Blue Economy in Seychelles; United Nations Economic Commission for Africa: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Finance, National Planning and Trade. Seychelles National Development Strategy 2019–2023. Government of Seychelles. 2018. Available online: http://www.finance.gov.sc/uploads/files/Seychelles_National_Development_Strategy_2019_2023_new.pdf (accessed on 23rd March 2023).

- Ministry of Finance, National Planning and Trade, ‘Vision 2033′. Government of Seychelles. Available online: http://www.finance.gov.sc/uploads/files/vision2033_vers_14_LR.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Failler, P.; Ayoubi, H.E. Seychelles Blue Economy Action Plan; Government of Seychelles: Victoria, Seychelles, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Secretariat. Sustainable Blue Economy Innovative Financing–Debt for Conservation Swap, Seychelles’ Conservation and Climate; Commonwealth Secretariat: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://production-new-commonwealth-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2022-02/Case%20Study%20-%20Innovative%20Financing%20%E2%80%93%20Debt%20for%20Conservation%20Swap,%20Seychelles%E2%80%99%20Conservation%20and%20Climate%20Adaptation%20Trust%20and%20the%20Blue%20Bonds%20Plan,%20Seychelles%20(on-going).pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Convergence. Seychelles Debt Conversion for Marine Conservation and Climate Adaptation: Case Study, Convergence; NatureVest. The Nature Conservancy: Arlington County, VA, USA, 2017. Available online: http://tinyurl.com/2dc6rkj5 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Silver, J.J.; Campbell, L.M. Conservation, development and the blue frontier: The Republic of Seychelles’ Debt Restructuring for Marine Conservation and Climate Adaptation Program. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2018, 68, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SeyCCAT. Blue Finance. The Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust. Available online: https://seyccat.org/blue-finance/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Mathew, J.; Robertson, C. Shades of blue in financing: Transforming the ocean economy with blue bonds. J. Invest. Compliance 2021, 22, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Application: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Allmark, P.; Boote, J.; Chambers, E.; Clarke, A.; McDonnell, A.; Thompson, A.; Tod, A.M. Ethical Issues in the Use of In-Depth Interviews: Literature Review and Discussion. Res. Ethics 2009, 5, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Sovereign Blue Bond Issuance: Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/10/29/sovereign-blue-bond-issuance-frequently-asked-questions (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. EU and Seychelles Take Stock of Fisheries Partnership. 2021. Available online: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-and-seychelles-take-stock-fisheries-partnership-2021-11-29_en (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- DBS. Development Bank of Seychelles. Annual Report for the Year 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.dbs.sc/sites/default/files/downloads/Merged%20Annual%20Report%20%26%20Financial%20Statement%20%202021.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Seychelles Blue Carbon–Blue Carbon Lab. Available online: https://www.bluecarbonlab.org/seychelles-blue-carbon/ (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- TNC. Mapping Ocean Wealth. Seychelles. Available online: https://oceanwealth.org/project-areas/seychelles/ (accessed on 31 September 2023).

- Arınç, O.K. Blue Bonds: Shifting the Responsibility Innovatively. Debt and Green Transition Blog Series. Available online: https://www.developmentresearch.eu/?p=1544 (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Samways, M.J.; Hitchins, P.M.; Bourquin, O.; Henwood, J. Restoration of a tropical island: Cousine Island, Seychelles. Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 19, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stobart, B.; Teleki, K.; Buckley, R.; Downing, N.; Callow, M. Coral recovery at Aldabra Atoll, Seychelles: Five years after the 1998 bleaching event. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2005, 363, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, B.S. Blue bonds for marine conservation and a sustainable ocean economy: Status, trends, and insights from green bonds. Mar. Policy 2022, 144, 105219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Bank and Credit Suisse Partner to Focus Attention on Sustainable Use of Oceans and Coastal Areas–the “Blue Economy”. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2019/11/21/world-bank-and-credit-suisse-partner-to-focus-attention-on-sustainable-use-of-oceans-and-coastal-areas-the-blue-economy (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Bollinger, P.A. Seychelles: Beyond Dramatic Imaginary. Samudra Report No. 82. 2020. Available online: https://aquadocs.org/bitstream/handle/1834/41223/Sam_82_art01_Seychelles_Svein_Jentoft.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Drakeford, B.M.; Failler, P.; Toorabally, B.; Kooli, E. Implementing the fisheries transparency initiative: Experience from the seychelles. Mar. Policy 2020, 119, 104060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF. Accelerating Innovation for Ocean Health. World Economic Forum 1000 Ocean Startups. Available online: https://www.1000oceanstartups.org/home (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Commonwealth Secretariat. The Commonwealth Blue Charter Project Incubator. Available online: https://thecommonwealth.org/bluecharter/commonwealth-blue-charter-project-incubator (accessed on 10 October 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).