1. Introduction

Substance-use disorders and the resulting overdose epidemic constitute a major public-health challenge in Canada, with a demonstrable negative impact on life expectancy according to a 2016 nationwide study [

1]. At the federal level, the most recent 2024 data show a modest improvement: compared with the previous year, there was an 11% decrease in deaths linked to opioid or other unregulated-drug poisonings and a 10% drop in related hospitalisations [

2].

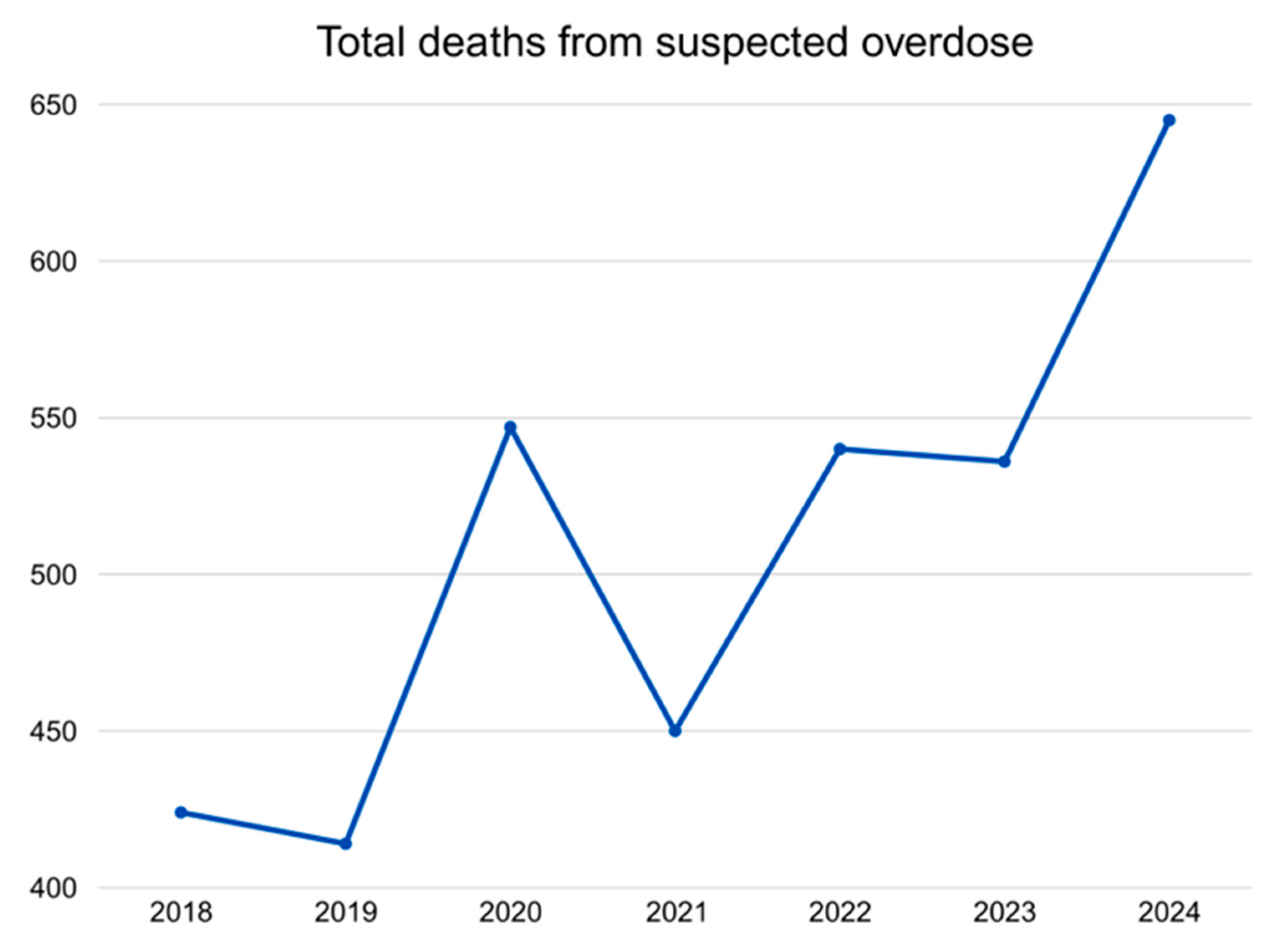

In Québec, however, the trend is moving in the opposite direction (

Figure 1). The annual death rate attributed to suspected opioid overdoses rose from 5.1 per 100,000 people in 2018 to 7.3 in 2024 [

3]. In Montreal, Canada’s second-largest urban centre, the crisis is deepening, as evidenced by rising numbers of supervised-consumption-site interventions, reported overdoses, emergency-department visits, naloxone administrations, and a 2.5-fold increase in naloxone distribution between 2020 and 2023 [

4]. This deterioration is occurring despite a series of countermeasures, including successive national strategies. Prescription opioid use seems to be an early driver of the Canadian opioid crisis. However, opioids in the illegal market are more often responsible for the death rates due to their toxicity.

We conducted a concise narrative review aimed at situating Québec’s overdose landscape within the broader Canadian context. To assemble the evidence base, we consulted federally maintained surveillance dashboards, Québec’s provincial drug-poisoning dashboards, and official publications from the Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux. To complement these grey-literature sources, we searched PubMed and Google Scholar for peer-reviewed studies and technical reports using combinations of terms related to opioid- and stimulant-related morbidity, mortality, treatment, and public-health interventions. Because narrative reviews do not mandate exhaustive retrieval, studies and reports were selected pragmatically, guided by the specific questions we sought to answer and by the availability of public dashboards. All included documents were read, and their findings were selected through qualitative thematic synthesis to identify recurring patterns, policy implications, and gaps in the current evidence.

Because data remain patchy, painting a full provincial picture is difficult. For example, stimulant-related deaths are rising nationally, yet complete Québec figures are available only up to 2021 [

5,

6]. Within the limits of the available data, this paper reviews the current landscape, outlines both population-level and clinical approaches, and highlights the challenges posed by the opioid- and stimulant-overdose crisis.

2. Opioid Situation in Québec

Québec’s illicit-opioid landscape has evolved rapidly from one dominated by sporadic heroin imports to a complex, poly-channel market that now includes high-potency synthetic analogues and diverted prescription products. Drug-seizure surveillance illustrates this shift: although stimulants, cannabis, and benzodiazepines still account for the majority of seized exhibits, the proportion containing opioids has risen steadily, and the chemical diversity of these opioids has expanded year on year [

7]. In the first quarter of 2025, Health Canada’s Drug Analysis Service catalogued 9121 samples from Québec, detecting two newly arrived nitazenes, protodesnitazene and N-pyrrolidino-metonitazene, compounds with µ-opioid–receptor activity that rivals, and in the latter case may double, the potency of fentanyl [

7,

8]. Such findings confirm that local markets are highly adaptive, importing or synthesising novel molecules almost as quickly as they appear on global early-warning lists.

Epidemiologically, the escalation is unmistakable. Provincial coroner data show that the proportion of suspected overdose deaths involving fentanyl or its analogues climbed from 33% in 2017 to 65% by September 2024 [

3]. Parallel public-health dashboards estimate that opioid poisoning now leads to approximately five deaths and fifteen hospital admissions every week, a burden that, while lower in absolute numbers than those recorded in British Columbia, Alberta, or Ontario, is rising against a backdrop of otherwise declining national mortality [

2,

4]. Modelling by Santé Canada indicates that such fatal poisonings have already eroded local life-expectancy gains made earlier in the decade [

1], underlining the crisis’ demographic reach.

Several pandemic-era forces accelerated these trends. Border disruptions, reductions in street-level policing, and clinic closures early in COVID-19 curtailed the heroin supply yet fostered the influx of cheaper, more compact fentanyl powders and tablets [

9]. Concurrently, an anxiolytic “spill-in” occurred: benzodiazepines, whether illicitly pressed or pharmaceutically diverted, were increasingly used to modulate fentanyl’s harsh kinetics, giving rise to so-called benzodope mixtures that induce prolonged respiratory depression poorly reversed by naloxone alone [

10]. Qualitative syntheses further document a surge in stimulant-plus-opioid co-use driven by users’ attempts to counter fentanyl’s sedating effects or to stretch diminished supplies, resulting in erratic dose stacking and unpredictable pharmacodynamic interactions [

6,

11].

For frontline clinicians, these adulteration patterns translate into toxidromes that challenge even seasoned emergency physicians: patients can present simultaneously agitated and hypoventilating, require repeated antagonist dosing, or develop delayed ventilatory failure after apparent stabilisation. Moreover, benzodiazepine co-intoxication complicates airway management and lengthens monitoring times, increasing emergency-department crowding during seasonal surges [

10]. Family physicians, traditionally gatekeepers for chronic-pain pharmacotherapy, now navigate a landscape in which every opioid prescription carries heightened diversion risk. The Équipe de soutien clinique et organisationnel en dépendance et itinérance (ESCODI) clinical guide therefore recommends routine opioid-use-disorder (OUD) screening at primary-care visits and endorses office-based, first-dose buprenorphine induction to shorten the referral pathway to formal OUD treatment [

12].

Psychiatric services have not been spared. Acute-care wards report a rising proportion of admissions complicated by covert opioid use or fulminant withdrawal, forcing psychiatrists to balance psychotropic optimisation with rapid OUD stabilisation and careful medication-interaction monitoring. Interdisciplinary liaison with addiction specialists, already standard for methadone and buprenorphine management, must now extend to safer-supply hydromorphone and other opioids being trialled under community protocols. Such coordination is explicitly encouraged in Québec’s 2022–2025 National Strategy on Psychoactive-Substance Overdose Prevention, which outlines seven pillars, awareness, harm reduction, public-policy adaptation, surveillance, research and evaluation, dependence treatment, and pain management, and calls for “integrated clinical pathways” that begin in the emergency department and continue through primary and specialist care [

9]. These pillars are highlighted in

Table 1.

Despite these policy ambitions, implementation gaps persist. Provincial dashboards track naloxone distribution and overdose reversals, both of which have increased by 2.5 and 3-fold, respectively, since 2020 [

13], yet do not consistently link this information to prescription-monitoring programmes or hospital discharge summaries. Consequently, clinicians often lack real-time feedback on a patient’s cumulative overdose risk or recent supervised-consumption-site (SCS) presentations, hampering continuity of care. Strengthening such data linkages, together with clinician training in nitazene recognition and benzodiazepine co-intoxication management, will be critical if Québec is to reverse its current upward trajectory.

Table 1.

Seven pillars identified in Québec’s 2022–2025 National Strategy on Psychoactive-Substance Overdose Prevention. Table adapted from the work of Bédard et al. [

14].

Table 1.

Seven pillars identified in Québec’s 2022–2025 National Strategy on Psychoactive-Substance Overdose Prevention. Table adapted from the work of Bédard et al. [

14].

| Pillar | Action Plans |

|---|

| Awareness | An “Every Life Counts” anti-stigma campaign broadcast on radio, social media, and transit shelters plus mandatory naloxone-trainer modules for pharmacy staff [14] |

| Harm reduction | Expansion of supervised-consumption services, introduction of drug-checking backed by mass-spectrometry confirmation, and province-funded safer-supply pilots [14,15] |

| Public-policy adaptation | Mobilising multiple government sectors to craft and test drug policies centred on the social and health needs of people who use psychoactive substance. For example, examining options such as decriminalising simple possession, and measuring the effects on the most vulnerable to steer evidence-based regulatory reform [14] |

| Surveillance | Regular coroner feeds, poison-centre calls, and supervised-consumption-site (SCS) overdose counts are merged into an INSPQ dashboard published online for patients and healthcare workers to consult [3,14] |

| Research and evaluation | Sustained backing for Québec’s overdose-related investigators, systematic knowledge-sharing, and continuous programme evaluation so that future actions stay firmly evidence-based [14] |

| Dependence treatment | Increased opioid agonist therapy (OAT) enrolment through more adaptable, flexible, and accessible services and expansion of the OAT service offer by introducing injectable OAT options for clients who do not respond to conventional options [14] |

| Pain management | Increasing access to alternative or complementary therapies and psychosocial support for chronic and non-cancer pain, while sharpening prescribing practices for opioids and other psychoactive substances in both community and specialised clinics [14] |

In summary, the province’s opioid crisis is characterised by an increasingly potent and chemically diverse supply, a rising toll of fatalities and hospitalisations, and a cascade of clinical challenges spanning emergency medicine, primary care, psychiatry, and specialised addiction treatment. Addressing these multilayered threats will require not only sustained harm-reduction investment but also robust policy-to-clinic feedback loops and an agile workforce equipped to manage the evolving toxicological landscape.

3. Stimulant Situation

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Québec has witnessed a sharp rise in harms linked to non-prescribed stimulants such as cocaine, amphetamine and, most conspicuously, methamphetamine. Federal Drug Analysis Service data show that stimulants now account for the largest share of all substances seized and analysed in the province, highlighting their ready availability and market dominance [

7]. Mortality surveillance conducted by the Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ) indicates that the mean monthly number of stimulant-attributable deaths climbed from 13 to 15 between 2017 and 2021, an upward trajectory that has persisted despite intensified enforcement [

6]. Nationally, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) reports a 44% increase in stimulant-involved fatalities between 2019 and 2023, with Québec contributing a growing proportion [

2]. Toxicology from provincial coroner investigations confirms that methamphetamine frequently co-occurs with fentanyl or its analogues, producing potentiated cardiotoxic and neuro-excitatory effects that are difficult to predict clinically [

3]. Pandemic-era supply chain disruptions constrained trans-continental cocaine routes, while inexpensive, domestically produced methamphetamine filled the resulting market gap, a trend acknowledged in Québec’s 2022–2025 overdose-prevention strategy [

9]. Episodic surveillance bulletins illustrate the practical impact of this adulteration: in May 2021, the Montréal regional public-health department documented a surge in emergency presentations for crack, cocaine, and methamphetamine toxicity in which respiratory depression was reversed only after naloxone administration, confirming fentanyl contamination of drugs not intended to contain opioids [

16]. Such findings mirror earlier warnings about “benzodope”, where benzodiazepines are pressed into opioid tablets. Another pattern, hidden opioids in stimulants, creates mixed toxidromes that can transition abruptly from hyperadrenergic agitation to life-threatening hypoventilation [

10]. Real-time PHAC dashboards likewise reveal a steady increase in emergency-department visits for stimulant poisoning that parallels the provincial mortality signal [

5].

These pharmacological and epidemiological shifts carry significant implications for clinicians across the continuum of care. In emergency departments, triage nurses and physicians must now assume concealed opioid exposure in every stimulant overdose, even when pupillary size and initial respiratory status appear reassuring; current protocols recommend routine point-of-care fentanyl testing when test strips are available and a low threshold for prophylactic naloxone during observation [

5,

10]. The presence of concurrent benzodiazepines further complicates airway management by prolonging sedation and dampening the ventilatory response to hypoxia. In community- and family-medicine settings, practitioners who already balance cautious opioid prescribing for chronic-pain syndromes increasingly confront co-existing stimulant-use disorder (StUD). The 2024 ESCODI clinical guide therefore advises documenting all psychoactive substance use via appropriate screening tools such as integrating structured StUD screening into the same visit when assessing opioid-use disorder (OUD) [

12]. Addiction medicine specialists are urging clinicians to offer contingency-management or bupropion-based interventions alongside buprenorphine or methadone initiation when appropriate, while psychiatric services report a growing caseload of methamphetamine-associated psychosis, often complicated by covert fentanyl withdrawal that exacerbates dysphoria, agitation, and suicidality; interdisciplinary liaison with addiction medicine is essential to stabilise OUD pharmacologically while addressing stimulant-induced psychosis through antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and environmental modulation. Finally, supervised-consumption sites (SCSs) have documented an increase in stimulant injections [

17], yet linkage of SCS overdose reversals to hospital records remains incomplete, limiting feedback loops that could alert clinicians to patients at highest risk. Collectively, these emerging clinical realities underscore the need for integrated protocols that equip emergency, primary-care workers and psychiatric teams to manage the dual threats of stimulant toxicity and concealed opioid exposure, thereby mitigating a trajectory of preventable morbidity and mortality in Québec.

4. Inequities and Social Determinants of Health

Substance-use patterns in Québec are tightly interwoven with long-standing social and historical inequities. Provincial surveillance programmes by the Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ) shows that census tracts in the lowest-income quintile record the highest drug-use prevalence, mirroring national findings from Statistics Canada that people with low income, limited education, and precarious employment are more likely to use opioid pain-relief medication more often and to report problematic use than their more advantaged peers [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Housing status further magnifies risk: a federal linkage study reported that 82% of people experiencing homelessness who died of acute toxicity had an opioid implicated and 67% had a stimulant implicated, proportions far exceeding those seen among housed decedents [

22]. Evidence from Montréal’s COSMO cohort paints a similar structural picture: roughly one-third of participants had been homeless in the preceding three months, and that instability independently raised the odds of sharing cookers, filters, and other injection paraphernalia by about 60%. Severe psychological distress also increased the likelihood of needle sharing, nearly doubling it [

23]. These social stressors erode safer-use practices and, by extension, sharpen the potential lethality of drug events.

Geography imposes additional challenges. Residents of rural and remote regions face long travel distances, seasonal road closures, and chronic shortages of prescribers and pharmacists. Recent INSPQ data also documents markedly higher substance use in high school students of sparsely populated administrative areas compared with urban Montréal or Québec City [

18,

24,

25]. Colonial legacies and systemic racism compound vulnerability for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples: community-specific reports describe earlier age of first opioid exposure, higher prevalence of polysubstance use, and reduced access to culturally safe treatment services, trends echoed in national dashboards that flag Indigenous communities as “among the hardest hit” by the current crisis [

26]. Immigrant populations present a nuanced picture: while first-generation newcomers typically report lower baseline substance use, Canadian-born children of immigrants rapidly converge toward, and sometimes exceed, mainstream usage levels, a trajectory attributed to acculturation stress, language barriers, and labour-market discrimination [

27]. Culturally safe care and harm-reduction models aimed at Indigenous communities or immigrant populations can help mitigate the disproportionate impact of the crisis on these populations. Home to 11 distinct Indigenous nations, Québec faces several intertwined challenges: advancing decolonisation, rebuilding trust with these communities, and indigenising harm-reduction programmes and strategies so they are truly relevant and effective for each group and their unique reality.

Psychological distress cuts across these structural determinants. Researchers link stimulant and opioid use to social isolation, job-related stress, and untreated mental-health disorders [

21,

23], drivers that intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic and remain elevated among service-sector and gig-economy workers. Converging federal hospital-discharge data indicate that roughly 43% of opioid-poisoning admissions and 56% of hospital stays for opioid-use disorder carry a concurrent mood or anxiety diagnosis, underscoring the bidirectional relationship between mental illness and substance use [

28]. Taken together, the evidence depicts a syndemic in which poverty, unstable housing, geographic isolation, colonial trauma, racial discrimination, and mental-health burden interact to concentrate opioid and stimulant harms in specific Québec sub-populations, demanding structural as well as individual-level interventions.

5. Population-Level Response by Government of Québec

Québec’s political response to the overdose crisis has evolved from an opioid-centred emergency plan into a broader, polysubstance public-health agenda. A ministerial inquiry launched in late 2017 drew on coroner data, police intelligence, and community hearings to map the early fentanyl surge and recommend a coordinated reaction. Its findings underpinned

Parce que chaque vie compte, the 2018–2020 National Strategy on Prevention and Response to Opioid Overdoses, which listed thirty-one actions, among them real-time mortality alerts, free take-home naloxone, and formal collaboration between health and justice sectors, and for the first time framed overdose as a provincial “collective responsibility” rather than an individual failing [

29]. Yet overdose deaths continued to rise instead of falling, and benzodiazepine-laced opioids, nitazenes, and stimulant co-poisoning quickly out-paced the plan’s opioid-only tools. In 2022, Québec’s Ministry of Health and Social Services replaced its opioid-focused roadmap with the 2022–2025 National Strategy on Prevention of Psychoactive-Substance Overdoses, a blueprint that expands the scope from opioids to all toxic psychoactive substances, puts a special emphasis on meeting the needs of First Nations, Inuit, and other remote communities across every region of the province, and sets the overarching goal of reducing overdose deaths province-wide, to be detailed in a forthcoming action plan [

9,

14]. Its architecture rests on the seven mutually reinforcing pillars presented in

Table 1.

Early implementation metrics suggest the framework is having an impact. Provincial surveillance shows that community-pharmacy distribution of free naloxone kits has kept climbing year over year, and the network of supervised-consumption sites has expanded from four Montréal locations in 2017 to more than a dozen operating across Québec today, widening life-saving coverage for people who use drugs [

4]. Supervised-consumption sites (SCSs) in Québec are federally sanctioned facilities where people can inject, inhale, snort, or swallow pre-obtained drugs under the watch of nurses, peer workers, and other harm-reduction staff. Fourteen services operate in the province as of mid-2025, all protected by section 56.1 exemptions that shield clients and staff from possession charges. Beyond providing a safe space and sterile supplies, these centres reverse overdoses, offer drug checking and rapid referrals, and many now include inhalation booths for people who do not inject.

In Québec, publicly funded addiction rehabilitation services are delivered through the province’s network of Dependence Rehabilitation Centres (CRD), which operate under each regional health authority (CISSS or CIUSSS). Anyone can access these services free of charge, and no physician referral is required. Users can access the services by calling Info-Social 811 or via regional intake lines. Interdisciplinary teams then provide a full continuum of care, from outpatient or inpatient detoxification and opioid-agonist treatment to external or residential rehabilitation, family support, and social reintegration programmes. To ensure province-wide coverage, the health authorities partner with dozens of certified community and private residential resources listed in a provincial registry, and they are mandated to maintain accessibility to this entire continuum under Québec’s 2018–2028 Interministerial Action Plan on Dependence.

Furthermore, IQVIA’s 2024 national dispensing report counts 13,694 Québec residents receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone in 2023, up from 11,743 in 2019, a 16% jump in four years, indicating that access to opioid-agonist therapy is widening alongside harm-reduction services [

30]. While more recent monitoring data are still pending, a published interrupted-time-series analysis of Montréal’s first four supervised-consumption sites and their impact from 2017 to 2019 found encouraging population-level effects. The authors documented a significant post-implementation decline in hospitalisations for injection-related infections (IRIs), including a downward trend in the subset that required surgery, indicating fewer severe complications over time. They also observed an initial rise in physician visits for skin-and-soft-tissue infections, which they interpret as evidence of earlier, less-acute care-seeking that may help prevent progression to more serious disease [

31]. These early signals suggest that Québec’s newer SCS now operating across the province could yield similar improvements as additional data become available.

Important gaps nevertheless hamper full realisation of the seven-pillar vision. Data streams from coroners, poison centres, and emergency departments still rely on incompatible coding schemes and siloed information technology platforms, delaying integrated situational awareness in most clinical settings. Rural inequity persists: even as tele-medicine pilots have boosted OAT retention in several remote communities, chronic shortages of prescribers and nursing staff, limited seasonal access to clinics and pharmacies, and the fact that some rural pharmacies do not regularly stock buprenorphine–naloxone or keep extended hours continue to hamper treatment uptake and continuity in northern regions [

25]. Workforce strain compounds existing structural gaps of a federal SCS. The Pandemic Impact Survey of site supervisors shows that reports of staff fatigue and low morale jumped from 32% in mid-2020 to 50% in 2021 and 57% in 2022, with open-ended responses blaming a rise in fatalities among peers and clients, overdose deaths from the drug toxicity crisis, and pandemic pressures [

32].

Future reports will judge whether Québec’s seven-pillar architecture delivers on its mortality reduction and health equity goals. If the early upticks in naloxone uptake, OAT enrolment and harm-reduction utilisation reflect better access rather than increased need. If the challenges of data integration, rural capacity-building, and stable funding are addressed, the province may yet reverse its overdose trajectory. Absent such reinforcements, however, the strategy risks becoming another well-intentioned plan stranded between political aspiration and on-the-ground realities.

6. Clinical Perspective and Approach

Clinicians hold a pivotal role in Québec’s overdose response: virtually every proven intervention—systematic screening, opioid-agonist prescribing, naloxone co-dispensing, contingency-management referral, etc.—still hinges on a medical or nursing order. The 2024 ESCODI clinical guide tells frontline physicians and nurses to use brief, validated tools such as the

Indice de gravité d’une toxicomanie at each assessment, stratify overdose risk, and, whenever OUD is suspected, initiate or arrange treatment the very same day rather than defer care [

12]. Yet a national cluster analysis of more than 13,000 overdose cases shows that no more than one quarter of high-risk patients were on opioid-agonist therapy at the time of their overdose, underscoring how many remain undiagnosed or untreated [

21]. Bringing primary-care practices up to ESCODI’s recommended universal-screening standard would therefore close a sizable treatment gap and capture thousands of Québec adults whose OUD currently goes unseen.

Pharmacists, and Québec’s network of more than 2000 community pharmacies, also play a key role in the surveillance, prevention, referral, and treatment of opioid-use disorder. They monitor prescribing patterns for signs of risk or misuse, provide patients with direct, evidence-based guidance on safe opioid use, distribute naloxone kits free of charge, and dispense safer-supply medications under rigorous protocols that ensure these harm-reduction measures are delivered safely and effectively.

7. Opioid-Use Disorder and Polysubstance Overdose

Large cohort studies confirm that medications for opioid-use disorder (MOUD), including OAT, are the single most effective clinical tools for preventing fatal overdose. Among Medicare beneficiaries who survived a non-fatal overdose, only 23% received MOUD within the following year, yet those treated experienced a 59% relative reduction in subsequent death compared with untreated peers [

33]. Community data from Baltimore show a clear dose-response: each additional month of methadone or buprenorphine coverage decreases recent-overdose odds by 7–10% and increases take-home-naloxone carriage [

34].

Naloxone co-prescribing amplifies MOUD’s impact. A JAMA Network Open analysis found that patients who received MOUD with naloxone had the lowest 12-month mortality of all comparator groups; those given MOUD without naloxone had intermediate benefit; and persons given naloxone alone enjoyed only transient protection [

35]. Québec’s provincial pharmacy programme already covers intranasal naloxone, and any resident aged 14 years or older can obtain it free of charge at community pharmacies, without a prescription. Yet a recent survey of more than 1000 recreational drug users found that six in ten respondents were not carrying naloxone despite being at ongoing risk of overdose [

36].

Integrated, multipronged care yields the greatest benefit. A New England Journal of Medicine cluster-randomised trial spanning 33 U.S. counties showed that counties implementing the

full bundle, MOUD scale-up, naloxone distribution, behavioural-health integration, and community-outreach navigators, achieved a 21% reduction in overdose deaths versus usual care over two years [

37]. The American College of Preventive Medicine therefore urges health systems to embed OUD pharmacotherapy, naloxone services, and behavioural-health linkages as routine preventive care, not specialist exceptions [

38]. Québec’s seven-pillar strategy aligns with this recommendation but still wrestles with a growing overdose epidemic [

4].

8. Stimulant-Use Disorder and Fentanyl-Contaminated Stimulants

The clinical calculus differs for stimulant-use disorder (StUD). No medication has yet matched MOUD’s efficacy; the American Society of Addiction Medicine/American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry (ASAM/AAAP) 2024 guideline instead designates contingency management (CM) as first-line therapy and urges clinicians to “offer immediate naloxone and drug-checking” to every patient using street stimulants because of pervasive fentanyl contamination [

39]. Comprehensive drug-checking, now available at several Québec supervised-consumption sites, combines fentanyl test strips with Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to identify benzodiazepines and nitazenes as well [

40,

41]. Addiction-psychiatry consensus papers stress that CM’s underuse stems not from lack of evidence but from reimbursement and regulatory obstacles [

42], barriers the province could mitigate through public-policy adaptation and by expanding its nascent CM initiative beyond specialised urban clinics.

Meanwhile, counselling alone is insufficient: a 2023 Preventive Medicine review warns of a “fourth wave” driven by psychomotor stimulants, with or without fentanyl in the United States [

43]. This “fourth wave” replicates the important rise in stimulant and stimulant-fentanyl overdoses reported by the Québec surveillance programmes. The authors advocate integrating StUD screening into every OUD intake, a step already adopted in the 2024 ESCODI revision, and prescribing take-home naloxone to all stimulant users, even those who deny opioid use [

12,

39].

9. Translating Evidence into Québec Practice

To operationalise this evidence, Québec clinicians can normalise universal screening for both OUD and StUD at primary-care, emergency departments, and psychiatry encounters using ESCODI and ASAM tools [

12,

39]. They can initiate or continue MOUD at point of contact, including post-overdose starts in the emergency department, and link patients to tele-OAT follow-up where local prescribers are scarce [

33,

37]. Co-prescribing intranasal naloxone and providing brief overdose-response training to patients and families at every MOUD or StUD visit, with automated pharmacy reminders to renew kits every 12 months, can also be routinely implemented [

35]. Clinicians should offer or refer to contingency management for stimulant users, ideally coupled with FTIR drug-checking and supervised-consumption services to mitigate fentanyl-related risk [

39,

42]. Multidisciplinary teams, including nurses, peer navigators, and social workers, can be leveraged to address housing, employment, and mental-health drivers that complicate adherence, reflecting findings that integrated behavioural health lowers mortality beyond pharmacotherapy alone [

37,

44].

By combining guideline-directed pharmacotherapy for OUD, harm-reduction tools for contaminated stimulants and evidence-based behavioural interventions, Québec’s clinicians can translate the seven-pillar provincial blueprint into tangible bedside practice, moving the province closer to its goals of reducing mortality and increasing health equity.

10. Conclusions

Québec now finds itself at a pivotal juncture in the evolving Canadian overdose landscape. Once buffered by lower opioid-prescribing rates and limited fentanyl penetration, the province has in recent years seen a steady rise in opioid- and stimulant-related mortality that contrasts sharply with the modest national decline. Our review documents how an increasingly heterogeneous supply laced with high-potency nitazenes, benzodiazepines, and ubiquitous fentanyl has collided with social dislocation, housing precarity, and service gaps to create a toxic syndemic. Monthly fatal-overdose counts have climbed despite the efforts of Parce que chaque vie compte, the 2018–2020 opioid strategy, suggesting that the containment tools of that era are no longer sufficient for today’s polysubstance reality.

The 2022–2025 National Strategy on Prevention of Psychoactive-Substance Overdoses represents a more comprehensive response. By embedding harm-reduction expansion, rapid toxicological surveillance, police diversion to treatment, province-funded drug checking, and stepped-care opioid-agonist therapy targets within a seven-pillar framework [

9], policymakers have signalled an appetite for structural rather than incremental change. Encouraging early indicators show that progress is attainable when policy, funding, and frontline capacity align. Yet stubborn disparities remain. Rural regions still face accessibility challenges, data silos impede real-time situational awareness in most clinical settings, and staff shortages or burnout among supervised-consumption and addiction-clinic staff threatens programme sustainability.

Clinical evidence underscores that medications for opioid-use disorder, coupled with naloxone co-prescribing and integrated behavioural care, are the most potent levers for preventing death [

33,

34,

35,

37,

38,

44]. For stimulant-use disorder, contingency-management programmes and drug-checking services offer the best available protection in the absence of approved pharmacotherapy [

39,

42,

43,

45]. Translating these interventions from journal pages to Québec medical schools, clinics, wards, and community settings is therefore the central clinical challenge of the next few years.

To face Québec’s overdose epidemic, health systems must accelerate three tasks. First, close the rural–urban gap by scaling tele-health opioid-agonist induction and funding travelling nurse-practitioner teams. Second, integrate toxicology and coroner feeds with emergency-department dashboards to give clinicians real-time awareness of local adulterant trends. Third, protect the workforce through sustainable funding, peer-support programmes and streamlined documentation.

This work, however, cannot be accomplished by policymakers alone. Physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, paramedics, and all frontline professionals who encounter people who use drugs hold the decisive keys. We urge every clinician in Québec to familiarise themselves with nearby supervised-consumption or drug-checking sites, know the hours of the closest rapid-access OAT clinic, and co-prescribe naloxone whenever opioids, licit or illicit, are in play. We further call on colleagues to read the 2022–2025 National Strategy in full [

9] and keep the ESCODI clinical guide at hand [

12] as a practical reference for screening, initiation of buprenorphine or methadone, and referral pathways.

In conclusion, clinicians can tackle the opioid crisis by the following:

Screen universally for OUD and StUD in primary-care, emergency departments, and psychiatry visits using ESCODI and ASAM tools.

Start or continue MOUD at all points of contact, including post-overdose in emergency departments; connect to tele-OAT if prescribers are limited.

Co-prescribe naloxone with brief overdose training at every MOUD or StUD visit; set reminders for annual kit renewal.

Refer to contingency management for stimulant users; pair with FTIR drug-checking and supervised consumption when possible.

Use multidisciplinary teams to address social and mental health barriers; integrated care improves outcomes beyond medication alone.

By coupling these evidence-based tools with an unwavering commitment to dignity, cultural safety, and equity, Québec’s healthcare community can transform policy aspiration into lived reality and, crucially, save lives.