Abstract

Over the last decades, new psychoactive substances (NPSs) have established a new pattern of drug synthesis and distribution. These compounds brought with them several challenges, including their analytical determination by known methodologies, the uncertainty of their toxicological effects, and the possible approaches used for control. In Brazil, the control of NPS started with a nominal list of proscribed compounds. But the variety of substances was so large that other strategies were implemented. Generic legislation was created as several groups began to emerge, such as phenethylamines, synthetic cathinones, and synthetic cannabinoids. The legislation also began to include salts and isomers of all listed substances and precursor chemical ingredients or plants that may be used to produce them. Those substances are known for the unpredictability of their effects, causing a wide range of symptoms, including seizures, aggression, and acute psychosis. Users under effect represent a high risk for themselves and others. In this study, we present an overview of the timeline in which NPSs were detected in Brazilian territory and the legislative approaches. A complete literature search was performed using PubMed, Scopus, the World Wide Web and Brazilian governmental websites employing relevant keywords such as NPS, legislation, and Brazil. Even with the high volume of legislative measures, the race against NPS intoxication cases and apprehensions continues to be fierce. There are limitations in the process of detection, identification, and prohibition of the substances in the country that demand a multifactorial approach, stronger public health measures, scientific research, as well as harm reduction strategies. Nevertheless, the Brazilian scenario on NPS arrival reflects a worldwide problem faced by many countries. In conclusion, it is stated that the use of multiple legislative strategies such as prohibition lists and generic controls can provide for better regulation of the NPS problem. However, this issue needs to be addressed by multiple organizations, including police departments and the public health system, and that effort needs to be coordinated and standardized for all Brazilian Federal states.

1. Introduction

New psychoactive substances (NPSs) are synthetic drugs that are intended to be alternatives to classic drugs, often mimicking their biological effects. However, they may have greater toxicity due to their high potency, requiring, generally, small doses to cause severe poisoning and even death [1,2,3]. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), NPSs can be defined as compounds that are not controlled by the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs or the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances. These compounds gained space in the market as “legal highs” since they were not controlled until years ago. Consequently, production and commercialization were not considered a crime, creating a legal loophole for drug trafficking [3,4,5]. However, this panorama has been modified over the last few years, especially in the last two decades, as hundreds of NPSs have been regulated and banned around the world. By the year 2022, 1182 new psychoactive substances had been reported worldwide to the UNODC [5].

According to the UNODC, drug-related deaths totaled nearly 500,000 in the period between 2010 and 2019. This number represents the deaths directly related to the consumption of drugs, but also the indirect deaths, commonly related to liver and infectious diseases and self-harm due to drug use [6]. However, it is very difficult to estimate the total number of deaths related only to NPSs, since not all toxicological analyses around the world cover these types of substances. This does not mean that there are not any data regarding NPS impairments. Several articles in the literature make an effort in describing cases with adverse effects of NPS use, related deaths, and detection of NPSs in people driving under the influence of drugs [1,7,8,9]. The control of NPSs is a challenge for the health and safety authorities because, with the regulations, other substances began to appear as replacements for the prohibited compounds. In this scenario, different legal strategies can be employed for effective control of these substances [10,11]. Prohibition of production, sale, and distribution can be made individually, for a specific chemical substance, or generically, for a group of substances with certain chemical similarities [12,13]. An example of nominal regulation is mephedrone, a synthetic cathinone that listed by name on the legislation [14]. Meanwhile, an example of generic regulation is the group of synthetic cathinones, which are regulated based on the cathinone molecule [15]. This prohibition is based on a generic chemical structure and seeks to reduce the propagation of new substances, foreseeing that all compounds with similar chemical characteristics, and consequently toxicological effects, are proscribed. This work aims to present an overview of the legal control of NPSs in Brazil, considering the history of these substances in the territory and the strategies adopted by the Brazilian authorities.

2. Overview of Substance Control in Brazil

The first report regarding substance control in Brazil was published in 1938, in the form of a presidential decree-law. Decree-Law No. 891 of 1938 introduced the prohibition and surveillance of narcotics, including opium and derivatives, marijuana, cocaine, and related products [16,17]. In the following decades, few effective alterations took place in this context. Important changes began in the 1980s, with the re-democratization of Brazil and, consequently, the creation of the Brazilian public health system. The Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) was implemented in 1988, and the legislations regarding it were published subsequently.

With the implementation, the necessity of a regulatory agency that would monitor health products, drugs, ingredients, facilities, and processes became clear. That requirement led to the creation of the National Health Surveillance Agency, known as ANVISA, abbreviated from the Portuguese: Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. ANVISA is linked to the Ministry of Health in the federal regulatory structure, and acts throughout the territory of the entire country, regulating all public health-related issues. The areas that ANVISA regulates include blood and blood products, cosmetics, medicines, food, health services, medical devices, sanitizing products, tobacco, and others [18]. In 1998, the Ministry of Health published Legislative Ordinance No. 344 of 1998, which lists, defines, and classifies special controlled substances. Table 1 shows how substances are divided in the ordinance. The list of substances can either be submitted to special control authorizations, have a limited concentration allowed, or be proscribed. It also lists precursors to proscribed substances and plants that may be used to produce those. Along with other drugs of abuse, known NPSs, as well as their salts and isomers, are included in the legislation as proscribed substances [19].

Table 1.

Classification by group of substances controlled by Legislative Ordinance No. 344 of 1998 from ANVISA.

However, the update of NPS lists should be as dynamic as their appearance. In 2015, ANVISA created the Substance Control Classification Workgroup by the Legislative Ordinance No. 898 of 2015. The permanent workgroup is composed of health, forensic, and law specialists, members of ANVISA, and the Brazilian Federal Police. It was constructed with the aim to discuss and improve the regulatory strategies, as well as optimize the updates to the lists of controlled substances [20,21]. Legislative Ordinance No. 344 of 1998 has been through 84 updates as of March of 2023, with the inclusion of new substances and reorganization of the lists.

In August 2021, the Brazilian National Council of Drug Policy experimentally created the National Subsystem of Rapid Alert About Drugs of Abuse (SAR). The primary objective of the SAR is to serve as a surveillance mechanism, specifically geared toward addressing the emergence of NPSs [22]. This initiative is similar to those already created in other regions, such as the European Union Early Warning System and the UNODC Early Warning Advisory (EWA) on NPSs. The operation of the system consists of a series of actions that include the detection, identification, characterization, and risk analysis of new substances or patterns of supply and demand. Those actions resulted in the elaboration of a warning containing all of the obtained useful information. The warning synthesizes specific information aiming to reach the public, police agents, experts, and health professionals [5,23].

3. NPS Distribution and Control in the Brazilian Territory

Several NPSs are present in the Brazilian market for illicit drugs. Over the last 10 years, Brazilian authorities identified over a hundred substances belonging to some of the most common classes defined by the UNODC [20,21,24]. Next, we present an overview of how these substances were first encountered in Brazil and the strategies that were established in order to control them.

3.1. Stimulants

The first case of NPSs in Brazil was registered in 2006 with the appearance of meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP), a piperazine derivate. This substance was identified in heart-shaped pills similar to ecstasy, which normally contains MDA, MDMA, and/or MDEA. The apprehension was made by the Federal Police in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul, which borders Paraguay [25]. After this particular case, mCPP was identified in several apprehensions throughout all of the Brazilian territories, becoming relevant in the country’s scenario, and added to the list of proscribed substances [26,27]. After the prohibition of mCPP, other substances appeared in the market as substitutes for the newest controlled drug. In 2010, a couple of forensic departments reported cases of ecstasy tablets that did not test positive for the commonly encountered substances. Further analysis revealed the presence of mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone), a synthetic cathinone, which was placed under national control in the next year [14,28]. Mephedrone was further placed under international control by its inclusion in the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances in 2015 [29]. The increased use of mCPP in ecstasy tablets and replacement by synthetic cathinones such as mephedrone were observed at the same time in the international scenario [30].

Synthetic cathinones also arrived in the country in the form of crystals or powders. Data show growth in the detection of this class of compounds during the last few years. This expansion was supported by the great increase in a particular substance: N-ethylpentylone. The first report of N-ethylpentylone (or ephylone) in Brazil was made in 2016, when the substance was detected in crystals and tablets. After that, several intoxication cases were reported, including some with serious and even fatal outcomes. In most cases, the patients reported the consumption of synthetic drugs, mainly ecstasy, as well as alcohol and other drugs at parties. In a fatal case from 2017, Costa et al. (2018) found 170 ng/mL of N-ethylpentylone in postmortem blood [31]. Additionally, Ferrari Júnior and Caldas (2022) found 597 ng/mL of N-ethylpentylone, also in postmortem blood, from a woman who died at a rave party in 2018 [32]. According to Souza Júnior et al. (2020), N-ethylpentylone was detected for the first time in 2016 through the analysis of seized tablets in the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina [33]. In the following year, the substance already represented 23% of the volume of seized tablets. The nominal regulation of N-ethylpentylone only began in March 2017 [34].

N-ethylpentylone came under control internationally only in 2019, and this was immediately reflected by its presence in seizures in Brazil. According to data from seizures carried out by the Federal Police, N-ethylpentylone was the most detected cathinone in 2017 and 2018, present in approximately 62% and 69% of reports containing synthetic cathinones, respectively [35]. However, the number of reports decreased from 158 in 2018 to 26 in 2019 (a drop of 83.5%), which the Federal Police justifies due to international control [36]. In 2018, eutylone was detected for the first time in Brazil, where it remained until 2020 as the most prevalent synthetic cathinone in federal seizures [35,37].

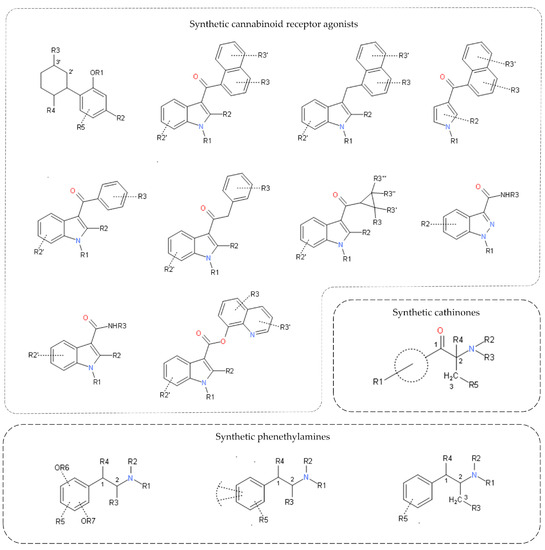

Considering the great distribution of these compounds and the health prejudices of the consumers, generic legislation for the synthetic cathinone groups (Legislative Ordinance No. 175 of 2017) was created in September 2017. Based on this legislation, all substances that presented a chemical structure similar to the ones represented in Figure 1 and a variety of described substitutions were automatically placed under national control [15]. Due to the effectiveness of this rule, numerous other synthetic cathinones that were identified for the first time in Brazil could already be classified as proscribed, e.g., eutylone, 4-fluoro-PHP, and 4-chloroethcathinone [21].

Figure 1.

Generic classification structures of synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRAs), synthetic cathinones, and synthetic phenethylamine groups.

This form of legislation was not needed for piperazines such as mCPP, since the class presents a minor variety of compounds that can be listed individually [38]. Additionally, there are few reports of piperazine-related compounds in Brazilian territory. Between 2014 and 2021, there was only one federal seizure of 3-trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine (TFMPP), a piperazine derivative. TFMPP, as well as benzylpiperazine, has been controlled since 2009 [24,37].

3.2. Hallucinogens

In parallel with the circulation of stimulant NPSs, other groups of importance in Brazil were NPSs with hallucinogenic properties, mainly belonging to the phenethylamines group. These substances were in general distributed in the form of paper blotters that usually contained LSD. The identification of NPSs in blotters in Brazil began in 2012 with the detection of NBOMe compounds. These compounds, including 25B-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe, and 25I-NBOMe, constituted a significant percentage of the synthetic drugs apprehended in the country for the next few years. Between 2012 and mid-2016, the Brazilian Federal Police released more than 180 reports for NBOMe compounds, marketed mainly in the form of blotters (about 83,000 units) [39]. In the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro, NBOMe compounds represented 90.5 and 96.7% of the substances detected on blotter papers in 2014 and 2015, respectively [40]. In 2014, the first fatal case of exposure to 25B-NBOMe was officially registered, a 20-year-old male student who drowned after exposure to the drug [41]. Other cases of intoxication were recorded in Brazil, emphasizing the high-risk behaviors for the user, such as reckless sexual exposure [42].

With the rise of NBOMe compounds in Brazil and the associated health risks, several substances of this class were placed under national control in 2014 [43]. The scenario became even more unfavorable with international control of 25B-NBOMe, 25I-NBOMe, and 25C-NBOMe in 2015 [29]. In 2019, the NBOMe compounds were present in only 2 analyses of federal seizures, showing a lack of interest in the commercialization of these substances [44].

Due to these regulations, a new family of compounds began to appear in blotters, the NBOH compounds. The substance 25I-NBOH was present in samples apprehended in Brazil in 2014, but its first identification was in 2015 [45]. In the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina, in 2015, 25I-NBOMe had a dominant presence in blotter papers, representing 41.4% of seized samples. In the following year, 25I-NBOH was already identified in 62.2% of the more than 30,000 samples analyzed [46]. Therefore, 25I-NBOH was placed under national control in 2016, culminating in the appearance of other derivatives, such as 25B-NBOH in 2017 and 25C-NBOH and 25E-NBOH in 2018 [35,47]. At the end of 2018, four 25R-NBOH compounds (R = Br, Cl, Et, H) were scheduled as illegal in Brazil [48]. The vast distribution of these compounds led to the creation of the generic legislation for the phenethylamines group in 2019—Legislative Ordinance No. 325 of 2019 [49]. Figure 1 presents the base chemical structure of phenethylamine, and any substitution in the molecule makes it nationally controlled.

Despite the control, NBOH compounds are consolidated in Brazil, representing a substantial amount of the substances commercialized in the form of blotter papers [35,36,50,51]. Nationally, 25I-NBOH was the seventh most detected synthetic drug in federal seizures in 2019 [36]. Moreover, 25E-NBOH was the fifth most detected synthetic drug in 2020 and remained the fourth most present in 2021 samples [24,37]. After the “boom” in synthetic cathinones in 2017 and 2018, mostly due to N-ethylpentylone, the outbreak of NBOH use returned the synthetic phenethylamines group to the top of NPSs identified by the Brazilian Federal Police, representing about 80% of total seizures in 2021 [24].

Poisoning cases involving NBOH compounds have been reported in recent years in Brazil [52]. One of the most serious was registered in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, where a male teenager consumed blotter paper sold as LSD. Hours later, he was found dead, and the toxicological analysis indicated the presence of 25E-NBOH in the organism, evidencing the considerable toxicity of synthetic phenethylamines [53]. Analyses of oral fluid from participants of Brazilian electronic music festivals and parties between September 2018 and January 2020 indicated 25I-NBOH and 25C-NBOH as the most detected synthetic phenethylamines. The two compounds represented, respectively, 3.9% and 2.2% of the positive samples for at least one NPS [54].

Other hallucinogenic groups, such as tryptamine derivatives or phencyclidine-type substances, can be mentioned. However, these classes of substances have a low incidence of seizures or poisoning cases in Brazil [55]. Compounds such as 5-MeO-DMT, 5-MeO-MiPT, and 3-MeO-PCP have already been detected in Brazilian territory. The first two have been prohibited since 2015, while 3-MeO-PCP was banned in 2018 [55,56].

In order to circumvent the legislation, a new model adopted by the drug market is the commercialization of prodrugs [57]. An example is ALD-52 (1A-LSD), metabolized in the body into LSD, which has hallucinogenic action. ALD-52 seizures began to occur in mid-2021, when the compound was not yet controlled by ANVISA and could be considered legal [58]. From that, ALD-52 and other LSD pro-drugs, such as 1B-LSD and 1P-LSD, were scheduled as illegal in February 2022, as of Legislative Ordinance No. 598 of 2022 [59].

3.3. Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists

The first detection of a synthetic cannabinoids in Brazil was made in 2009, with the identification of the substance JWH-018. By that time, synthetic cannabinoids were mainly apprehended in the form of herb mixtures similar to Spice. This way, several herbs with or without psychoactive properties were blended, and a solution containing the synthetic substances was pulverized in this material, in order to resemble weed [60]. JWH-018 was put under national control a year later, and in 2015, it was included in the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances [29,61].

Even so, this group of substances is extremely diverse, since several synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists (SCRAs) do not have a similar chemical structure but are able to produce an effect on the cannabinoid receptors [62,63]. The chemical diversity and the possibility of synthesizing new substituted compounds led to the creation of generic legislation for SCRAs in Brazil in 2016. Unlike the regulations enacted for synthetic cathinones and phenethylamines, this legislation included 10 different chemical structures that could be used as a base molecule for the synthesis of new compounds. All 10 structures are represented in Figure 1, while the legislation also described possible common modifications [64].

These compounds currently represent a serious public health issue in Brazil. Since 2016, police forces have come across a new way to distribute SCRAs, which is through paper impregnation. In 2022, Rodrigues et al. (2022) reported the identification of several SCRAs in 56 paper samples apprehended in Brazilian prisons during a period of 5 years. Most of the samples were from the last couple of years, which demonstrates the increase in these substances in Brazilian territory. Regarding the identified compounds, the most prevalent were MDMB-4en-PINACA and 5F-MDMB-PICA [65]. In the Brazilian State of São Paulo, seizures of synthetic cannabinoids have increased exponentially, currently representing the most prevalent synthetic drug class. Some SCRAs such as ADB-BUTINACA were detected 50 times more often in 2021 in comparison to 2020. Furthermore, in the first four months of 2023, approximately 15 kg of drugs containing SCRAs were withdrawn from circulation. This number is already higher than the totals seized throughout 2021 (5.7 kg) and 2022 (11.7 kg) [66]. Lastly, another unusual SCRA, BZO-HEXOXIZID (or MDA-19), was present in more than 50 seizures carried out in the São Paulo state between September 2021 and February 2022. Mostly, it was identified in herbal preparations, and some of the samples had other concomitant substances, e.g., ADB-BUTINACA, tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), and cocaine [67]. Despite being controlled by generic legislation, BZO-HEXOXIZID and other similar SCRAs were nominally controlled after their appearance in Brazil [59].

These drugs are also rapidly being distributed on the streets as well under the name of “K” compounds (K2, K4, and K9). Therefore, some in the homeless population who used to be crack cocaine users have begun shifting their habits toward the consumption of SCRAs. Data from the city of São Paulo indicates almost 500 suspected cases of intoxication with SCRAs in the first six months of 2023. This represents a five-fold increase in the notifications when compared to the entire year of 2022 and about 13% of cases of intoxication by drugs of abuse in the first half of 2023 [68]. Currently, SCRAs represent the most detected class of NPSs in cases of poisoned patients attended by the Poison Control Center of Campinas, located in the State of São Paulo. MDMB-4en-PINACA is the most prevalent SCRA, followed by ADB-BUTINACA and 5F-MDMB-PINACA [66].

The generic structural classification has proved to be efficient over the last few years, comprising the SCRAs that appeared in the country. Despite this, ANVISA has nominally listed numerous NPSs already generically regulated, such as ADB-BUTINACA and MDMB-4en-PINACA. Such action emphasized the need for strict control of these substances, due to the high toxicity and associated health risk.

3.4. Other Substances

Historically, the profile of Brazilian substance consumption has been based on the use of stimulant substances. This can be confirmed when the data on stimulant NPSs are observed. However, other substances that represent a global menace to public health are constantly being monitored in order to evaluate if they can become a problem in Brazil. This is the case with synthetic opioids, which nowadays are one of the biggest public health issues in the United States. Brazilian data regarding these drugs show that apprehensions of fentanyl have been made since 2009 and continued into the present year. Fentanyl is a regulated pharmaceutical for hospital use in Brazil but already has been found as a substitute for, or mixed with, LSD, synthetic cannabinoids, and cocaine [69]. Some fentanyl analogs such as furanylfentanyl were detected in blotter papers sold as LSD in 2018 [70]. However, its presence was isolated, with no further reports in Brazilian territory. Furanylfentanyl was placed under national control in 2018 [56]. All synthetic opioids are controlled nominally, as there is no generic regulation for this group since the prevalence of cases is rare compared to other mentioned groups.

Another group of NPSs that has recently emerged on the global market, and consequently in Brazil, is the synthetic benzodiazepines group. Synthetic or designer benzodiazepines are not approved for therapeutic use in Brazil, as their clinical effects and safety are unknown. Among these substances, bromazolam was one, in particular, capable of raising a red flag among Brazilian authorities. This concern was justified after a fatal case occurred in 2022, when a 37-year-old man was found dead at a hotel in the state of Espírito Santo. The toxicological analysis primarily blamed the death on the consumption of cocaine, sildenafil, sertraline, and alcohol. The detection of bromazolam was only confirmed a year later. Around the same period in 2022, a seizure of almost 4000 blotters was made in the same state [71]. This important seizure and other minor ones led to the inclusion of bromazolam in the national list of proscribed substances in November 2022 [72].

4. Discussion

The use of NPSs is a worldwide public health concern, with the constant arrival of individuals in intoxication centers or in need of hospital care. In countries that have a universal health system such as Brazil, drug intoxications represent large expenses to the government. Every illegal substance, including NPSs, is produced in clandestine laboratories. For that reason, these products do not undergo quality control processes or tests for safety, potency, and purity. The dose of the substance can vary even in the same batch, as was demonstrated in the work of Barbosa et al. (2019) [70]. Unlike regulated pharmaceuticals, the effects of the substances are not predictable, and production is not standardized. Beyond that, the addition of adulterants and bulk agents is a common strategy to increase profits. These agents can vary massively and enhance the health risks already present in the consumption of NPSs.

New psychoactive substances arrive in the same rhythm—or faster—as the list of proscribed substances grows. Although the control of these substances is essential, research studies that may illustrate the real risks and impacts are also needed. In the current scenario, the country has an extensive list of proscribed substances without substantive knowledge about their effects and toxicity, since the acquisition of these substances, even for scientific purposes, is heavily restricted. The dynamism of the drug market and high costs linked to reference standards often complicate analytical confirmation, whether in the context of seized materials or in cases of in vivo or post-mortem poisoning.

Limitations exist in statistical data regarding NPS apprehension and poisoning cases in Brazil, and it is possible that the number of occurrences is underestimated. Not all Federal States are equipped or have the capacity to detect these substances, due to their wide range of chemical structures. The fact that it is not possible to differentiate increases or decreases in exposures from sub-notification creates a challenge in inferring epidemiologic information. That is an important aspect to take into consideration when analyzing whether tightened regulations are working, or if the substances are simply not being detected.

Nevertheless, there is no integrated system capable of listing all data on NPS detection obtained from the different spheres responsible for this type of analysis, such as the Federal Police, the Brazilian States Police, and the Poison Control Centers. Brazil is a vast country with internal regions that differ massively in geographic, economic, and cultural aspects. The contradictory visions between governors and state representatives makes it difficult to establish efficient drug combat policies as a general priority. In addition, research entities have historical issues related to financial investments from public agencies, which have been aggravated in recent years. These difficulties directly affect a continuous advance in drug use prevention and substance control.

Brazilian legislation regarding substance control started to be published very recently and has slowly improved. ANVISA proved to be efficient in many cases of NPS appearance in Brazilian territory, promoting the rapid restriction of several drugs. The synthesis and implementation of controls based on a generic structure enabled Brazilian authorities to move forward in combating the drug market. Different NPSs, such as eutylone, ADB-FUBINACA, and dozens more, were already considered proscribed even before the first case in which they were detected [21]. Despite the inclusion of numerous substances in the generic classification, ANVISA continued to nominally prohibit NPSs previously included, in order to reinforce the idea of maximum control. Furthermore, the combination of generic regulation and individual listing approaches can provide better management of NPSs’ control and, consequently, may reduce their commercialization and consumption by the population [73].

The generic control model is a mechanism adopted by numerous countries besides Brazil. The model was based on examples of countries like the USA, European countries, and Japan, implementing the first group (SCRAs) only in 2016. This approach has its advantages, such as agility and prospecting the control of possible NPS analogs [74]. Despite this, the implementation of this type of control could have been faster, allowing the inclusion of a larger range of structural classes as soon as possible. The national control of synthetic phenethylamines by generic structure occurred only in 2019, even with high rates of NBOMe compounds between 2012 and 2016 and the emergence of NBOH compounds in 2017.

An important aspect that a legislator should consider is that all drugs are not under his control using this methodology [9,13]. In addition, regulatory authorities must pay attention to the control of therapeutic substances based on their chemical similarities with controlled structures, so as not to interfere with the therapeutic use and scientific studies of these compounds [75].

Other forms of control can be used to control NPS expansion. One of them is the blanket ban, already adopted since the mid-2010s by countries like New Zealand, Ireland, and Australia. Unlike the rules adopted in Brazil, any substance with psychoactive effects that is not approved for medical or scientific use is automatically considered banned [76]. This action can facilitate the containment of drug trafficking and the application of punishments by the judicial authorities. Despite proposing a strong control, the blanket ban is controversial, since it can affect the pharmaceutical development of new therapeutic drugs. As only the substances present in Legislative Ordinance No. 344 of 1998 are considered proscribed in Brazilian territory, seizures of loads containing NPSs were already considered legal in Brazil, since the substances were not yet regulated at the time of seizure [77]. If it were considered a blanket ban scenario in these cases, such an action would be framed as a crime.

Brazil is not typically a producer of synthetic drugs. The demand for NPSs and other synthetic drugs is mainly supplied by European and Asian countries. With this scenario, more effective control happens when international or mutual national restrictions on the substance make the importation processes difficult. Examples of this type of situation are the behavior of the markets for N-ethylpentylone and NBOMe compounds. Both NPSs were already nationally controlled and even so, had a high prevalence in Brazilian territory. It was only after the international banning and inclusion in the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances that there was a significant decrease in the circulation of these compounds.

The Rapid Alert Subsystem was only implanted in 2021, even though the first NPS detected in Brazil dates to 2006. That indicates a relatively slow response to the emerging problem of NPS abuse and distribution in the country. This point is reinforced when analyzing legislation related to traffic and driving under the influence of drugs (DUID) in Brazil. Several studies have shown an association between the use of NPSs and DUID [9,78,79]. Brazil has specific laws for testing psychoactive substances, e.g., cocaine and MDMA, in professional drivers. However, no NPS is included in the legislation, opening space for the use of such substances in this context [80]. Obviously, analytical and logistical challenges are involved in this perspective, as well as in the forensic chemistry and clinical toxicology testing scenario.

Finally, surveillance of the market, as well as the effective diagnosis of clinical and post-mortem poisoning cases through toxicological analysis, should be reinforced in order to verify the NPS trends in society. Nevertheless, monitoring classic drugs should be maintained, given the possibility of changing trends in NPS use due to the unavailability of these substances on the market. The solution to containing NPSs depends not only on banning measures, but, through the encouragement of harm reduction actions, discussions of a more conscious use, and implementation of public health actions.

5. Conclusions

NPSs are characterized as an emerging and complex global health and security problem. Carrying out the control of new compounds is challenging since the drug market is extremely dynamic due to an accelerated rate of synthesis and consumption trends. With this, the authorities must use strategies capable of allowing adequate regulation and, consequently, the prevention of cases of intoxication and associated social problems. ANVISA normally formulates its legislation on NPSs based on what is implemented internationally, mainly in the European countries and United States, since these regions have been dealing with NPSs for a longer period of time. However, faster approaches are needed in their implementation. Several legal strategies can be used, such as individual and generic control, as is currently applied in Brazil. However, an important aspect to consider is that even though comprehensive legislations like generic legislation are helpful in outlawing NPSs that may not yet be on the market, they also impair the research for new drugs that can be used for therapeutic purposes.

It is important to state that legislative measures alone are not enough to cover this multifaceted dilemma. Strict prohibition strategies exacerbate the lack of information for the user and ricochet to public health in any country. For Brazil, all efforts should be focused on implementing a reliable infrastructure in the Brazilian Federal States to enable the rapid detection of new substances, accelerating the process of adding them to the legislation, as well as training specialized professionals to handle the health challenges through harm reduction strategies and proper support in cases of intoxication. Additionally, awareness strategies should be implemented with marketing of official channel reports and information to the general population, considering that they are the final interested party. The reports are available on governmental websites, but they do not seem to attract the attention of users that return to potentially harmful references over the internet.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, B.P.d.S., L.B. and P.d.S.S.; Conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition, S.E. and T.F.d.O.; Conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition, M.D.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, grant number FAPERGS/MS/CNPq 08/2020—PPSUS21/2551-0000101-1 and by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—Brazil (CAPES—Finance Code 001).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kraemer, M.; Boehmer, A.; Madea, B.; Maas, A. Death Cases Involving Certain New Psychoactive Substances: A Review of the Literature. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 298, 186–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, A.; Bruno, R.; Gisev, N.; Degenhardt, L.; Hall, W.; Sedefov, R.; White, J.; Thomas, K.V.; Farrell, M.; Griffiths, P. New Psychoactive Substances: Challenges for Drug Surveillance, Control, and Public Health Responses. Lancet 2019, 394, 1668–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simão, A.Y.; Antunes, M.; Cabral, E.; Oliveira, P.; Rosendo, L.M.; Brinca, A.T.; Alves, E.; Marques, H.; Rosado, T.; Passarinha, L.A.; et al. An Update on the Implications of New Psychoactive Substances in Public Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafi, A.; Berry, A.J.; Sumnall, H.; Wood, D.M.; Tracy, D.K. New Psychoactive Substances: A Review and Updates. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 10, 204512532096719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. UNODC Early Warning Advisory on New Psychoactive Substances. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/LSS/Page/NPShttps://www.unodc.org/LSS/Page/NPS (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. UNODC Online World Drug Report—Latest Data and Trend Analysis. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/wdr-2023-online-segment.html (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Mohr, A.L.; Logan, B.K.; Fogarty, M.F.; Krotulski, A.J.; Papsun, D.M.; Kacinko, S.L.; Huestis, M.A. Ropero-Miller, J.D. Reports of adverse events associated with use of novel psychoactive substances, 2017–2020: A review. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2022, 46, 116–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fels, H.; Herzog, J.; Skopp, G.; Holzer, A.; Paul, L.D.; Graw, M.; Musshoff, F. Retrospective analysis of new psychoactive substances in blood samples of German drivers suspected of driving under the influence of drugs. Drug Test. Anal. 2020, 12, 1470–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, S.M.R.; Richeval, C.; Nachon-Phanithavong, M.; Gaulier, J.M.; Di Fazio, V.; Humbert, L.; Samyn, N.; Allorge, D. Prevalence of new psychoactive substances and prescription drugs in the Belgian driving under the influence of drugs population. Drug Test. Anal. 2017, 10, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikura-Hanajiri, R.; Kawamura, N.U.M.; Goda, Y. Changes in the Prevalence of New Psychoactive Substances before and after the Introduction of the Generic Scheduling of Synthetic Cannabinoids in Japan. Drug Test. Anal. 2014, 6, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Maida, N.; Di Trana, A.; Giorgetti, R.; Tagliabracci, A.; Busardò, F.P.; Huestis, M.A. A Review of Synthetic Cathinone-Related Fatalities From 2017 to 2020. Ther. Drug Monit. 2021, 43, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, P.; Pardo, B. New Psychoactive Substances: Are There Any Good Options for Regulating New Psychoactive Substances? Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 40, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Amsterdam, J.; Nutt, D.; Van Den Brink, W. Generic Legislation of New Psychoactive Drugs. J. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 27, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 36, de 03 de Agosto de 2011: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2011. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 175, de 15 de Setembro de 2017: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Brasil. Decreto-Lei No 891, de 25 de Novembro de 1938. Available online: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/declei/1930-1939/decreto-lei-891-25-novembro-1938-349873-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Machado, L.V.; Boarini, M.L. Drug Policies in Brazil: The Harm Reduction Strategy. Psicol. Ciência e Profissão 2013, 33, 580–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-Ba, K.; Beumer Sassi, A. ANVISA: An Introduction to a New Regulatory Agency with Many Challenges. AAPS Open 2018, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANVISA. Portaria n.o 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998: Aprova o Regulamento Técnico Sobre Substâncias e Medicamentos Sujeitos a Controle Especial. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 1998. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- ANVISA. Relatório de Atividades 2015/2016: Grupo de Trabalho Para Classificação de Substâncias Controladas; Brasília, 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/novas-substancias/arquivos/6668json-file-1 (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- ANVISA. Relatório de Atividades 2017/2018: Grupo de Trabalho Para Classificação de Substâncias Controladas; Brasília, 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/novas-substancias/arquivos/6669json-file-1 (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública. Subsistema de Alerta Rápido Sobre Drogas—SAR. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mj/pt-br/assuntos/sua-protecao/politicas-sobre-drogas/subsistema-de-alerta-rapido-sobre-drogas-sar/subsistema-de-alerta-rapido-sobre-drogas (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- EMCDDA. Early Warning System on NPS. Available online: https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/topic-overviews/eu-early-warning-system_en#section2 (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Polícia Federal. Drogas Sintéticas: Relatório 2021; Brasília, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.br/pf/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/relatorio-de-drogas-sinteticas-2021/relatorio_drogas_sinteticas_2021___versao_final___revisado_ljm___edb_assinado_assinado.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Paulo, F.D.S. Novo Tipo de Ecstasy Cresce no País. Available online: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/cotidian/ff0301201012.htm (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Maldaner, A.O.; Schmidt, L.L. Another Drug of Abuse: 1-(3-Chlorophenyl) Piperazine (MCPP). In 32a Reunião Anual da Sociedade Brasileira de Química; Sociedade Brasileira de Química, Ed.; Sociedade Brasileira de Química: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2009; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 79, de 04 de Novembro de 2008: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2008. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Ambrósio, J.C.L. O Crescimento Do Uso de Drogas Sintéticas “Legais” No Brasil. Perícia Fed. 2012, 29, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations: Commission on Narcotic Drugs. Report on the Fifty-Eighth Session (5 December 2014 and 9–17 March 2015); 2015. Available online: https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210577335 (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Brunt, T.M.; Poortman, A.; Niesink, R.J.M.; Van Den Brink, W. Instability of the Ecstasy Market and a New Kid on the Block: Mephedrone. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 25, 1543–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.L.; Cunha, K.F.; Lanaro, R.; Cunha, R.L.; Walther, D.; Baumann, M.H. Analytical Quantification, Intoxication Case Series, and Pharmacological Mechanism of Action for N-Ethylnorpentylone (N-Ethylpentylone or Ephylone). Drug Test. Anal. 2019, 11, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari Júnior, E.; Caldas, E.D. Determination of New Psychoactive Substances and Other Drugs in Postmortem Blood and Urine by UHPLC–MS/MS: Method Validation and Analysis of Forensic Samples. Forensic Toxicol. 2022, 40, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Júnior, J.L.; Silveira Filho, J.; Boff, B.S.; Nonemacher, K.; Rezin, K.Z.; Schroeder, S.D.; Ferrão, M.F.; Danielli, L.J. Seizures of Clandestinely Produced Tablets in Santa Catarina, Brazil: The Increase in NPS from 2011 to 2017. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 65, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 143, de 17 de Março de 2017: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Polícia Federal. Drogas Sintéticas: Relatório 2018; Brasília, 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.br/pf/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/relatorio-de-drogas-sinteticas-2018/drogas_sinteticas_2018.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Polícia Federal. Drogas Sintéticas: Relatório 2019; Brasília, 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.br/pf/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/relatorio-de-drogas-sinteticas-2019/relatorio_drogas_sinteticas_2019.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Polícia Federal. Drogas Sintéticas: Relatório 2020; Brasília, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.br/pf/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/relatorio-de-drogas-sinteticas-2020/relatorio_drogas_sinteticas_2020.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Arbo, M.D.; Bastos, M.L.; Carmo, H.F. Piperazine Compounds as Drugs of Abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012, 122, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayhs, C.A.Y.; dos Reis, M.; Mariotti, K.D.C.; Romão, W.; Vaz, B.G.; Ortiz, R.S.; Limberger, R.P. NBOMe: Perfil de Apreensões Da Polícia Federal No Brasil. Rev. Bras. Crim. 2016, 5, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, V.L.; de Oliveira, A.S.; Cohen, L.S.A.; Bhering, C.D.A.; de Oliveira, K.M.; de Siqueira, D.S.; de Oliveira, M.A.M.; Aquino Neto, F.R.D.; Vanini, G. Chemical and Statistical Analyses of Blotter Paper Matrix Drugs Seized in the State of Rio de Janeiro. Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 318, 110588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulo, F.D.S. Estudante Encontrado Morto Usou Droga E Se Afogou Na USP, Diz Laudo. Available online: https://m.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2014/10/1533238-estudante-encontrado-morto-usou-droga-e-se-afogou-na-usp-diz-laudo.shtml (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Remy, L.; Marchi, N.; Scherer, J.; Fiorentin, T.R.; Limberger, R.; Pechansky, F.; Kessler, F. NBOMe: A New Dangerous Drug Similar to LSD. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2015, 37, 351–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 06, de 18 de Fevereiro de 2014: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília, 2014. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Yasin Wayhs, C.A.; Tortato, C.; De Cássia Mariotti, K.; Scorsatto Ortiz, R.; Pereira Limberger, R. New Psychoactive Substances Constant State of Flux: NBOMe Brazilian Case. Brazilian J. Forensic Sci. Med. Law Bioeth. 2021, 11, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantes, L.C.; Júnior, E.F.; de Souza, L.F.; Cardoso, A.C.; Alcântara, T.L.F.; Lião, L.M.; Machado, Y.; Lordeiro, R.A.; Neto, J.C.; Andrade, A.F.B. 25I-NBOH: A New Potent Serotonin 5-HT2A Receptor Agonist Identified in Blotter Paper Seizures in Brazil. Forensic Toxicol. 2017, 35, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza Boff, B.; Silveira Filho, J.; Nonemacher, K.; Driessen Schroeder, S.; Dutra Arbo, M.; Rezin, K.Z. New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) Prevalence over LSD in Blotter Seized in State of Santa Catarina, Brazil: A Six-Year Retrospective Study. Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 306, 110002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 117, de 19 de Outubro de 2016: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 254, de 10 de Dezembro de 2018: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 325, de 3 de Dezembro de 2019: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Machado, Y.; Coelho Neto, J.; Lordeiro, R.A.; Silva, M.F.; Piccin, E. Profile of New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) and Other Synthetic Drugs in Seized Materials Analysed in a Brazilian Forensic Laboratory. Forensic Toxicol. 2019, 37, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birk, L.; de Oliveira, S.E.F.; Mafra, G.; Brognoli, R.; Carpes, M.J.S.; Scolmeister, D.; Carasek, E.; Merib, J.D.O.; de Oliveira, T.F. A Low-Voltage Paper Spray Ionization QTOF-MS Method for the Qualitative Analysis of NPS in Street Drug Blotter Samples. Forensic Toxicol. 2020, 38, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subsistema de Alerta Rápido Sobre Drogas. Terceiro Informe Do Subsistema de Alerta Rápido Sobre Drogas (SAR); Brasília, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mj/pt-br/assuntos/sua-protecao/politicas-sobre-drogas/subsistema-de-alerta-rapido-sobre-drogas-sar/terceiro-informe-sar-3nov.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- IGP-RS. Droga Sintética Que Causou Morte de Jovem é Identificada Pelo IGP. Available online: https://igp.rs.gov.br/identificacao-de-nova-droga-sintetica-desafia-o-igp (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- da Cunha, K.F.; Oliveira, K.D.; Cardoso, M.S.; Arantes, A.C.F.; Coser, P.H.P.; Lima, L.D.N.; Maluf, A.C.S.; Comis, M.A.D.C.; Huestis, M.A.; Costa, J.L. Prevalence of New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) in Brazil Based on Oral Fluid Analysis of Samples Collected at Electronic Music Festivals and Parties. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 227, 108962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 49, de 11 de Novembro de 2015: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2015. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 227, de 17 de Maio de 2018: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Elliott, S.P.; Holdbrook, T.; Brandt, S.D. Prodrugs of New Psychoactive Substances (NPS): A New Challenge. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 65, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, L.F.N.; Fabris, A.L.; Barbosa, I.L.; de Carvalho Ponce, J.; Martins, A.F.; Costa, J.L.; Yonamine, M. Lucy Is Back in Brazil with a New Dress. Forensic Sci. Int. 2022, 341, 111497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 598, de 09 de Fevereiro de 2022: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Alves, A.D.O.; Spaniol, B.; Linden, R. Synthetic Cannabinoids: Emerging Drugs of Abuse. Arch. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 21, de 17 de Junho de 2010: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2010. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Alves, V.L.; Gonçalves, J.L.; Aguiar, J.; Teixeira, H.M.; Câmara, J.S. The Synthetic Cannabinoids Phenomenon: From Structure to Toxicological Properties. A Review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2020, 50, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, A.J.; Banister, S.D.; Irizarry, L.; Trecki, J.; Schwartz, M.; Gerona, R. “Zombie” Outbreak Caused by the Synthetic Cannabinoid AMB-FUBINACA in New York. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 79, de 23 de Maio de 2016: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998, e Dá Outras Providências. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Rodrigues, T.B.; Souza, M.P.; de Melo Barbosa, L.; de Carvalho Ponce, J.; Júnior, L.F.N.; Yonamine, M.; Costa, J.L. Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists Profile in Infused Papers Seized in Brazilian Prisons. Forensic Toxicol. 2022, 40, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subsistema de Alerta Rápido Sobre Drogas. Quinto Informe Do Subsistema de Alerta Rápido Sobre Drogas (SAR); Brasília, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mj/pt-br/assuntos/sua-protecao/politicas-sobre-drogas/subsistema-de-alerta-rapido-sobre-drogas-sar/5o-informe-sar-canabinoides-sinteticos-07-07-2023.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- De Araujo, K.R.G.; Fabris, A.L.; Neves Júnior, L.F.; de Carvalho Ponce, J.; Soares, A.L.; Costa, J.L.; Yonamine, M. The Mystery behind the Apprehensions of the Selective Cannabinoid Receptor Type-2 Agonist BZO-HEXOXIZID (MDA-19) as a Drug of Abuse. Forensic Toxicol. 2023, 41, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prefeitura do Município de São Paulo. Relatório Epidemiológico—PMPCI No 122023; São Paulo, 2023. Available online: https://www.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/cidade/secretarias/upload/saude/12_%20Relat%C3%B3rio%20Epidemiol%C3%B3gico%20Canabinoide%20sintetico_PMPCI%20SE%2029(1).pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Subsistema de Alerta Rápido Sobre Drogas. Quarto Informe Do Subsistema de Alerta Rápido Sobre Drogas (SAR); Brasília. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mj/pt-br/assuntos/sua-protecao/politicas-sobre-drogas/subsistema-de-alerta-rapido-sobre-drogas-sar/4o_informe_sar-02-05-2023.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2023).

- De Melo Barbosa, L.; Santos, J.M.; de Morais, D.R.; Nimtz, A.V.; Eberlin, M.N.; de Oliveira, M.F.; Costa, J.L. Fast UHPLC-MS/MS method for analysis of furanylfentanyl in different seized blotter papers. Drug Test. Anal. 2019, 11, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polícia Civil do Espiríto Santo. Perícia Capixaba Identifica Droga Que Não Possuía Registro no Brasil e Confirma o Primeiro Óbito Causado Pela Substância. Available online: https://pc.es.gov.br/Notícia/pericia-capixaba-identifica-droga-que-nao-possuia-registro-no-brasil-e-confirma-o-primeiro-obito-causado-pela-substancia (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- ANVISA. Resolução—RDC No 762, de 24 de Novembro de 2022: Dispõe Sobre a Atualização Do Anexo I (Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras Sob Controle Especial) Da Portaria SVS/MS No 344, de 12 de Maio de 1998. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária: Brasília 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/controlados/lista-substancias (accessed on 29 July 2023).

- Neicun, J.; Roman-Urrestarazu, A.; Czabanowska, K. Legal Responses to Novel Psychoactive Substances Implemented by Ten European Countries: An Analysis from Legal Epidemiology. Emerg. Trends Drugs Addict. Heal 2022, 2, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, O.A.; Chuang, P.J.; Tseng, Y.J. Comparison of Controlled Drugs and New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) Regulations in East and Southeast Asia. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 138, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, P.V.; Power, J.D. New Psychoactive Substances Legislation in Ireland—Perspectives from Academia. Drug Test. Anal. 2014, 6, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, M.J.; Seear, K.; Lancaster, K. A critical examination of the definition of ‘psychoactive effect in Australian drug legislation. Int. J. Drug Policy 2017, 40, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consultor Jurídico. Só há Crime de Tráfico se Substância for Listada Como Entorpecente e Ilegal. Available online: https://www.conjur.com.br/2017-mai-18/crime-trafico-substancia-for-listada-entorpecente (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Richeval, C.; Wille, S.M.R.; Nachon-Phanithavong, M.; Samyn, N.; Allorge, D.; Gaulier, J.M. New Psychoactive Substances in Oral Fluid of French and Belgian Drivers in 2016. Int. J. Drug Policy 2018, 57, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institóris, L.; Hidvégi, E.; Kovács, K.; Jámbor, Á.; Dobos, A.; Rárosi, F.; Süvegh, G.; Varga, T.; Kereszty, É.M. Drug Consumption of Suspected Drug-Influenced Drivers in Hungary (2016–2018). Forensic Sci. Int. 2022, 336, 111325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CONTRAN. Resolução Contran No 923, de 28 de Março de 2022: Dispõe Sobre o Exame Toxicológico de Larga Janela de Detecção, Em Amostra Queratínica, Para a Habilitação, Renovação Ou Mudança Para as Categorias C, D e E, Decorrente Da Lei No 13.103, de 02 de Março de 2. Conselho Nacional de Trânsito: Brasília 2022. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-contran-n-923-de-28-de-marco-de-2022-390343520 (accessed on 29 July 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).