The Impact of Empathy and Perspective-Taking on Medical Student Satisfaction and Performance: A Meta-Ethnography and Proposed Bow-Tie Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

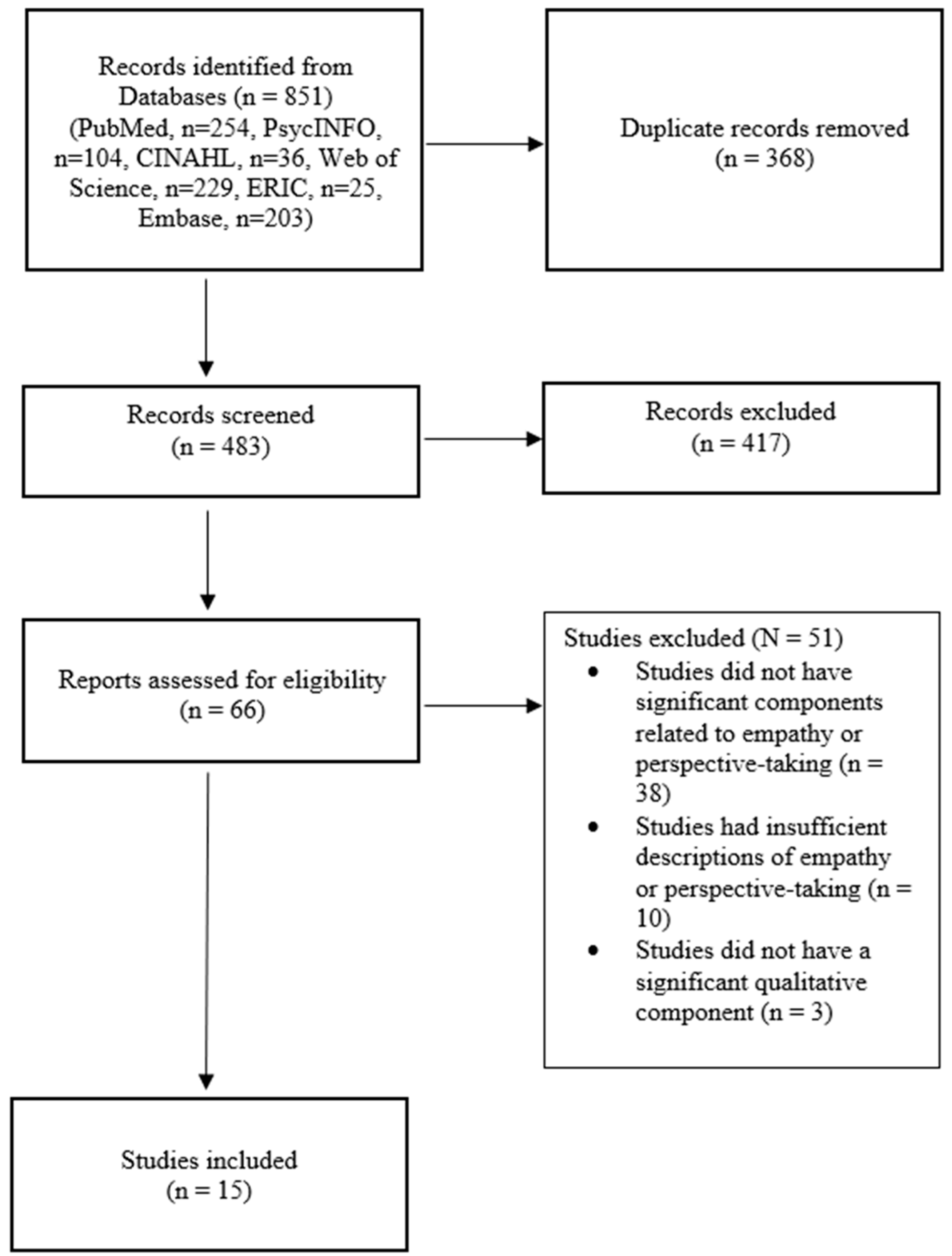

2. Materials and Methods

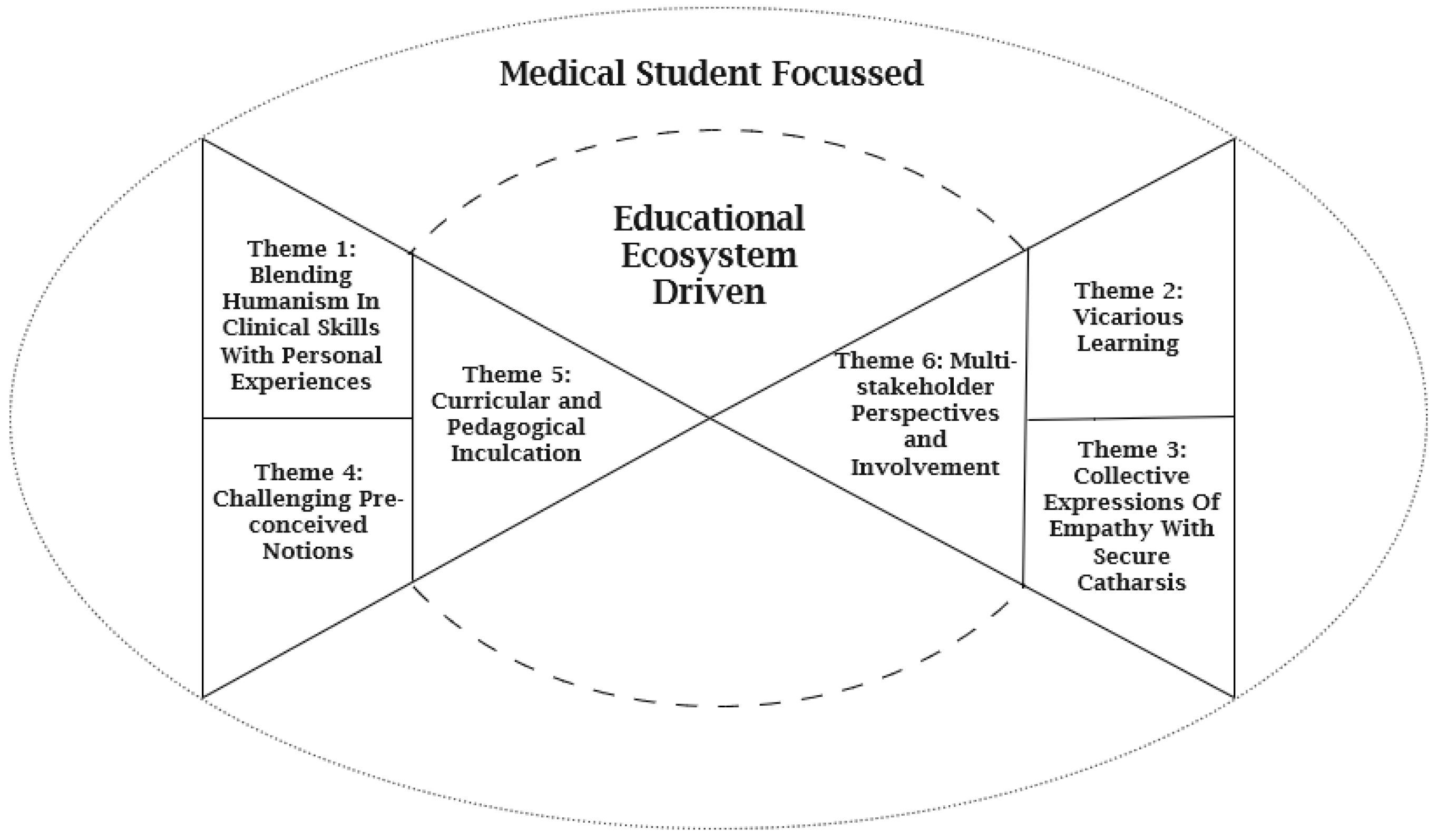

3. Results

3.1. Medical-Student-Focused Efforts

3.1.1. Theme 1: Blending Humanism in Clinical Skills with Personal Experiences

3.1.2. Theme 2: Vicarious Learning

3.1.3. Theme 3: Collective Expressions of Empathy with Secure Catharsis

3.1.4. Theme 4: Challenging Pre-Conceived Notions

3.2. Medical Education Ecosystem Driven

3.2.1. Theme 5: Curricular and Pedagogical Inculcation

3.2.2. Theme 6: Multi-Stakeholder Perspectives and Involvement

3.2.3. Specific Details

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nembhard, I.M.; David, G.; Ezzeddine, I.; Betts, D.; Radin, J. A systematic review of research on empathy in health care. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojat, M.; Louis, D.Z.; Markham, F.W.; Wender, R.; Rabinowitz, C.; Gonnella, J.S. Physicians’ Empathy and Clinical Outcomes for Diabetic Patients. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeliki, K.; Kristine, B.; Zackary, B.; Amy, E.C.B. The need for empathetic healthcare systems. J. Med. Ethics 2021, 47, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R. Empirical research on empathy in medicine—A critical review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 76, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, J. What is Clinical Empathy? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertakis, K.D.; Roter, D.; Putnam, S.M. The relationship of physician medical interview style to patient satisfaction. J. Fam. Pract. 1991, 32, 175–181. [Google Scholar]

- The Medical School Objectives Writing Group. Learning objectives for medical student education–guidelines for medical schools: Report I of the Medical School Objectives Project. Acad. Med. 1999, 74, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojat, M.; Vergare, M.J.; Maxwell, K.; Brainard, G.; Herrine, S.K.; Isenberg, G.A.; Veloski, J.; Gonnella, J.S. The devil is in the third year: A longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, M.; Edelhäuser, F.; Tauschel, D.; Fischer, M.R.; Wirtz, M.; Woopen, C.; Haramati, A.; Scheffer, C. Empathy decline and its reasons: A systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 996–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.C.; Kirshenbaum, D.S.; Yan, J.; Kirshenbaum, E.; Aseltine, R.H. Characterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical school. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojat, M.; Shannon, S.C.; DeSantis, J.; Speicher, M.R.; Bragan, L.; Calabrese, L.H. Does Empathy Decline in the Clinical Phase of Medical Education? A Nationwide, Multi-Institutional, Cross-Sectional Study of Students at DO-Granting Medical Schools. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, R.; Ismail, S.; Shraim, M.; El Hajj, M.S.; Kane, T.; El-Awaisi, A. Experiences of burnout, anxiety, and empathy among health profession students in Qatar University during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stietz, J.; Jauk, E.; Krach, S.; Kanske, P. Dissociating Empathy from Perspective-Taking: Evidence from Intra- and Inter-Individual Differences Research. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobchuk, M.; Hoplock, L.; Halas, G.; West, C.; Dika, C.; Schroeder, W.; Ashcroft, T.; Clouston, K.C.; Lemoine, J. Heart health whispering: A randomized, controlled pilot study to promote nursing student perspective-taking on carers’ health risk behaviors. BMC Nurs. 2018, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanske, P.; Böckler, A.; Trautwein, F.-M.; Singer, T. Dissecting the social brain: Introducing the EmpaToM to reveal distinct neural networks and brain–behavior relations for empathy and Theory of Mind. NeuroImage 2015, 122, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, R. Empathy development in medical education—A critical review. Med. Teach. 2010, 32, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Pelletier-Bui, A.; Smith, S.; Roberts, M.B.; Kilgannon, H.; Trzeciak, S.; Roberts, B.W. Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt-Rawden, S.A.; Chisolm, M.S.; Anton, B.; Flickinger, T.E. Teaching empathy to medical students: An updated, systematic review. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blatt, B.; LeLacheur, S.F.; Galinsky, A.D.; Simmens, S.J.; Greenberg, L. Does perspective-taking increase patient satisfaction in medical encounters? Acad. Med. 2010, 85, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, S.E.; Gilliland, K.O.; McNeil, C.; Royal, K. The Flipped Classroom Improved Medical Student Performance and Satisfaction in a Pre-clinical Physiology Course. Med. Sci. Educ. 2015, 25, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Cuyegkeng, A.; Breuer, J.A.; Alexeeva, A.; Archibald, A.R.; Lepe, J.J.; Greenberg, M.L. Medical student exam performance and perceptions of a COVID-19 pandemic-appropriate pre-clerkship medical physiology and pathophysiology curriculum. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Eyck, R.P.; Tews, M.; Ballester, J.M. Improved medical student satisfaction and test performance with a simulation-based emergency medicine curriculum: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009, 54, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairi, I.; Ben Dhiab, M.; Mzoughi, K.; Ben Mrad, I.; Kraiem, S. Assessing medical student satisfaction and interest with serious game. Tunis Med. 2021, 99, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, M.J. Examining the Relationship Between Medical Student Satisfaction and Academic Performance in a Pre-Clinical, Flipped-Classroom Curriculum; Wright State University: Dayton, OH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Paro, H.B.; Silveira, P.S.; Perotta, B.; Gannam, S.; Enns, S.C.; Giaxa, R.R.; Bonito, R.F.; Martins, M.A.; Tempski, P.Z. Empathy among medical students: Is there a relation with quality of life and burnout? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazeau, C.M.L.R.; Schroeder, R.; Rovi, S.; Boyd, L. Relationships Between Medical Student Burnout, Empathy, and Professionalism Climate. Acad. Med. 2010, 85, S33–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Shi, M.; Li, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M.; Wu, H. Empathy, burnout, life satisfaction, correlations and associated socio-demographic factors among Chinese undergraduate medical students: An exploratory cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, V.; Bearman, M.; MacLeod, A. Understanding Meta-Ethnography in Health Professions Education Research. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2023, 15, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpass, A.; Shaw, A.; Sharp, D.; Walter, F.; Feder, G.; Ridd, M.; Kessler, D. “Medication career” or “moral career”? The two sides of managing antidepressants: A meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of antidepressants. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblit, G.W.; Hare, R.D. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Samieefar, N.; Momtazmanesh, S.; Ochs, H.D.; Ulrichs, T.; Roudenok, V.; Golabchi, M.R.; Jamee, M.; Lotfi, M.; Kelishadi, R.; Tabari, M.A.K.; et al. Integrated, Multidisciplinary, and Interdisciplinary Medical Education. In Multidisciplinarity and Interdisciplinarity in Health; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 607–622. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, F.J.; Darok, M.C.; Ho, L.; Holstrom-Mercader, M.S.; Freiberg, A.S.; Dellasega, C.A. The Impact of an Unconventional Elective in Narrative Medicine and Pediatric Psycho-oncology on Humanism in Medical Students. J. Cancer Educ. 2021, 37, 1798–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corr, M.; Roulston, G.; King, N.; Dornan, T.; Blease, C.; Gormley, G.J. Living with ‘melanoma’... for a day: A phenomenological analysis of medical students’ simulated experiences. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, I.S.; Bogetz, A.L.; Long, M.; Kind, T.; Ottolini, M.; Lineberry, M.; Bhansali, P. Medical student perspectives on conducting patient experience debrief interviews with hospitalized children and their families. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chretien, K.C.; Swenson, R.; Yoon, B.; Julian, R.; Keenan, J.; Croffoot, J.; Kheirbek, R. Tell Me Your Story: A Pilot Narrative Medicine Curriculum During the Medicine Clerkship. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, A.K.; Murphy, E.A.; Ross, P.T. Diabetes stories: Use of patient narratives of diabetes to teach patient-centered care. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2009, 14, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearsley, J.H.; Lobb, E.A. ‘Workshops in healing’ for senior medical students: A 5-year overview and appraisal. Med. Humanit. 2014, 40, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, R.; Hagen, M.G.; Zaidi, Z.; Dunder, V.; Maska, E.; Nagoshi, Y. Self-care perspective taking and empathy in a studentfaculty book club in the United States. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2020, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntfield, S.L.; Slesar, K.; Dickson, J.; Charon, R. Narrative medicine as a means of training medical students toward residency competencies. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 91, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieffestahl, A.M.; Risor, T.; Mogensen, H.O.; Reventlow, S.; Morcke, A.M. Ignitions of empathy. Medical students feel touched and shaken by interacting with patients with chronic conditions in communication skills training. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 1668–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojan, J.N.; Sun, E.Y.; Kumagai, A.K. Persistent influence of a narrative educational program on physician attitudes regarding patient care. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, G.; Osborne, A.; Carroll, M.; Carr, S.E.; Etherton-Beer, C. Do photographs, older adults’ narratives and collaborative dialogue foster anticipatory reflection (“preflection”) in medical students? BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J. Project-based learning approach to increase medical student empathy. Med. Educ. Online 2020, 25, 1742965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, A.H.; Underman, K. Clinical empathy as emotional labor in medical work. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 251, 112904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennrikus, E.F.; Skolka, M.P.; Hennrikus, N. Social Constructivism in Medical School Where Students Become Patients with Dietary Restrictions. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2020, 11, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, M.V.; Orlando, M.S.; Rand, C.S.; Record, J.; Christmas, C.; Ziegelstein, R.C.; Hanyok, L.A. Medical students’ perceptions of the patient-centredness of the learning environment. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2017, 6, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, E.; Swartzlander, B.J.; Gugliucci, M.R. Using virtual reality in medical education to teach empathy. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 498–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godley, B.A.; Dayal, D.; Manekin, E.; Estroff, S.E. Toward an Anti-Racist Curriculum: Incorporating Art into Medical Education to Improve Empathy and Structural Competency. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2020, 7, 2382120520965246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovlid, E.; Bukve, O. A qualitative study of contextual factors’ impact on measures to reduce surgery cancellations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, H.S.; Anthony, D.; Hutchinson, T.A.; Liben, S.; Smilovitch, M.; Donato, A.A. Professional identity formation in medical education for humanistic, resilient physicians: Pedagogic strategies for bridging theory to practice. Acad. Med. 2015, 90, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, D. A meta-ethnography of interview-based qualitative research studies on medical students’ views and experiences of empathy. Med. Teach. 2016, 38, 1214–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.-C.; Tan, C.K.N.; Tan, K.; Yee, X.J.; Jion, Y.; Roebertsen, H.; Dong, C. How community and organizational culture interact and affect senior clinical educator identity. Med. Teach. 2024, 46, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.L.; Johnston, C.B.; Singh, B.; Garber, J.D.; Kaplan, E.; Lee, K.; Teherani, A. A “safe space” for learning and reflection: One school’s design for continuity with a peer group across clinical clerkships. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 1560–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacita, A.; Gargus, E.; Uchida, T.; Garcia, P.; Macken, M.; Seul, L.; Brucker, J.; Wayne, D.B. Introduction to Safe Space Training: Interactive Module for Promoting a Safe Space Learning Environment for LGBT Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL 2017, 13, 10597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.A.; Nixon, L.; McClurg, C.; Scherpbier, A.; King, N.; Dornan, T. Experience of Touch in Health Care: A Meta-Ethnography Across the Health Care Professions. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 28, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.-F.; Chin, T.M.K.; Lee, Z.-Y.; Tseng, G.-F. Silent Mentor programme increases medical students’ empathy levels. Med. Educ. 2023, 57, 1128–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masnoon, N.; Shakib, S.; Kalisch-Ellett, L.; Caughey, G.E. Tools for Assessment of the Appropriateness of Prescribing and Association with Patient-Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Drugs Aging 2018, 35, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosettenstein, K.R.; Lain, S.J.; Wormleaton, N.; Jack, M.M. A systematic review of the outcomes of false-positive results on newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism. Clin. Endocrinol. 2021, 95, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Leach, M.; Bradley, H. The effectiveness and safety of ginger for pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting: A systematic review. Women Birth 2013, 26, e26–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufford, L.; Newman, P. Bracketing in Qualitative Research. Qual. Soc. Work 2010, 11, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, S.; Lewin, S.; Smith, H.; Engel, M.; Fretheim, A.; Volmink, J. Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toye, F.; Seers, K.; Allcock, N.; Briggs, M.; Carr, E.; Andrews, J.; Barker, K. ‘Trying to pin down jelly’—Exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.D.; Blacksmith, J.; Reno, J. Utilizing insider-outsider research teams in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 2000, 10, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, D. Ethnomethodological insights into insider-outsider relationships in nursing ethnographies of healthcare settings. Nurs. Inq. 2004, 11, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assing Hvidt, E.; Ulsø, A.; Thorngreen, C.V.; Søndergaard, J.; Andersen, C.M. Weak inclusion of the medical humanities in medical education: A qualitative study among Danish medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, E.L.; Blinderman, C.D.; Cross, I. Reconsidering Empathy: An Interpersonal Approach and Participatory Arts in the Medical Humanities. J. Med. Humanit. 2021, 42, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verduin, M.L.; Balon, R.; Coverdale, J.H.; Louie, A.K.; Beresin, E.V.; Roberts, L.W. The Rising Cost of Medical Education and Its Significance for (Not Only) Psychiatry. Acad. Psychiatry 2014, 38, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavlin, D.; Jubbal, K.T.; Noé, J.G.; Gansbacher, B. A comparison of medical education in Germany and the United States: From applying to medical school to the beginnings of residency. Ger. Med. Sci. 2017, 15, Doc15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Databases | Number of Studies |

|---|---|

| PubMed | 254 |

| PsycINFO | 104 |

| Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) | 36 |

| Web of Science | 229 |

| Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC) | 25 |

| Embase | 203 |

| Total | 851 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, C.T.; Lim, L.J.H.; Tang, H.; Gupta, G.; Sung, I.C.H.; Dong, C. The Impact of Empathy and Perspective-Taking on Medical Student Satisfaction and Performance: A Meta-Ethnography and Proposed Bow-Tie Model. Int. Med. Educ. 2025, 4, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4040043

Tang CT, Lim LJH, Tang H, Gupta G, Sung ICH, Dong C. The Impact of Empathy and Perspective-Taking on Medical Student Satisfaction and Performance: A Meta-Ethnography and Proposed Bow-Tie Model. International Medical Education. 2025; 4(4):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4040043

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Chao Tian, Lucas Jun Hao Lim, Haoming Tang, Gaytri Gupta, Isabelle Chiao Han Sung, and Chaoyan Dong. 2025. "The Impact of Empathy and Perspective-Taking on Medical Student Satisfaction and Performance: A Meta-Ethnography and Proposed Bow-Tie Model" International Medical Education 4, no. 4: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4040043

APA StyleTang, C. T., Lim, L. J. H., Tang, H., Gupta, G., Sung, I. C. H., & Dong, C. (2025). The Impact of Empathy and Perspective-Taking on Medical Student Satisfaction and Performance: A Meta-Ethnography and Proposed Bow-Tie Model. International Medical Education, 4(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4040043