Abstract

Recognizing and understanding the nuances of mental health and how issues can present at various levels of healthcare for both patients and the interprofessional (IP) healthcare team can be crucial for the success and well-being of team members, as well as for achieving positive patient outcomes. Learners from various allied healthcare disciplines participated in a Case-Based Learning-Sequential Disclosure Activity (CBL-SDA) to address navigating appropriate approaches to fostering wellness in the clinical encounter and within healthcare teams from a multidisciplinary perspective. The CBL-SDA was delivered to a cohort of allied health students (N = 90) using a 4-step process during an interprofessional education (IPE) event of (i) Orientation, (ii) Sequential Disclosure, (iii) IPE Forum, (iv) Wrap-up. Pre- and post-activity surveys were voluntarily collected to gauge participants’ perceptions of the content and delivery method, with a response rate of 90% (N = 81). Overall, participants reported gaining confidence in their understanding of wellness, in identifying and providing support for a person struggling with wellness, in having tools to promote wellness, and also rated their own wellness higher, following the one-hour training session. It can be concluded that IPE activities highlighting wellness and mental health are beneficial and necessary in allied health care training.

1. Introduction

The growing demands and complexity of modern healthcare have underscored the urgent need to prioritize both clinician well-being and collaborative practice. Burnout, moral distress, and mental health challenges are increasingly prevalent among healthcare trainees, with implications for individual performance, patient outcomes, and system sustainability [1,2]. Education and apprenticeship in the healthcare professions are inherently rigorous and often associated with high levels of stress, burnout, anxiety, and depression among students and trainees [3]. These challenges not only compromise the personal health and academic performance of learners but also have downstream effects on patient care and professional sustainability. Addressing wellness in medical education is thus both a moral imperative and a strategic priority. Integrating wellness promoting strategies such as mindfulness training, peer support, workload management, and reflective practice can enhance emotional resilience, empathy, and professional identity formation [4]. As the healthcare landscape evolves to prioritize holistic, patient-centered care, fostering the well-being of future physicians must be embedded as a foundational element of medical curricula, rather than treated as a supplementary concern. In response, wellness has emerged as a critical component of healthcare education [5,6,7,8]. Yet, traditional medical education professional training models often fail to address the interconnectedness of personal well-being and team-based care.

Interprofessional education (IPE), which involves learners from two or more health professions learning with, from, and about each other, offers a promising framework to integrate wellness into healthcare training [9]. By fostering mutual respect, communication, and psychological safety, IPE has been shown to improve teamwork, reduce hierarchical stress, and enhance learners’ sense of belonging all key protective factors against burnout [10,11]. Effective healthcare can only be accomplished when the expertise and skills of each member of the healthcare team are accessible and utilized. An individual’s ability to perform at their level best can be affected by a verity of factors, not least of which being their overall wellness. Wellness should be nurtured by the whole healthcare team, both for the patient and caregivers [12]. Moreover, interprofessional environments that emphasize shared values, reflective practice, and peer support can promote emotional resilience and professional fulfillment [13,14]. As healthcare systems move toward collaborative care models, embedding wellness-promoting strategies into IPE not only supports individual well-being but also prepares future professionals for the interpersonal and emotional demands of clinical practice [4]. It is important to recognize and understand the nuances of mental health care and how it can present at various levels of the healthcare process for both the patient as well as the care team, in order to be able to find solutions and ensure the highest possible quality of care [15]. To address the current gaps in understanding of how to navigate appropriate approaches to fostering wellness in the clinical encounter and within healthcare teams, we created a Case Based Learning -Sequential Disclosure Activity (CBL-SDA) focusing specifically on this topic from a multidisciplinary perspective, similar in format to previously published methods [16]. The goal of this learning tool is to provide intentional interprofessional learning experiences that help prepare future clinicians for interprofessional collaboration and the complex care of their patients in clinical settings. By leveraging a scenario-based discussions with participants from various allied healthcare training backgrounds, learners were encouraged to voice their thoughts and experiences to learn from one another and be better prepared for the unique demands of dealing with wellness in the interdisciplinary clinical setting [17,18].

This paper explores how IPE initiatives can be leveraged to cultivate wellness among healthcare trainees and how these approaches can be systematically integrated into curricula to support a more compassionate, collaborative, and sustainable healthcare workforce.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants:

Learners enrolled in health professions programs from seven Nova Southeastern University (NSU) colleges and 10 programs (Table 1) took part in NSU’s IPE Day in February 2024. Learners were provided documentation about the study, and the contact information of the researchers, as well as the opportunity to opt out of the study. This study, involving human subjects, was reviewed and exempted by the Nova Southeastern University Institutional Review Board (IRB # 2021-12-NSU). Learners who chose to be participants in this study provided their written informed consent using an online Microsoft Form.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics Distribution Table (n = 81).

Procedure:

During the NSU IPE Day 2024, learners were randomly assigned into groups of thirty, and the wellness training session was held a total of three times with unique groups. Each session had a participation rate of approximately 90 ± 1% (N = 81) for the study, with approximately equal participation from each group.

Objectives for the IP-CBL-SDA Session are; (i) Demonstrate being receptive to opinions of members of an interprofessional team with a wellness-centered perspective, (ii) Recognize effects of inadequate training and proficiency for mental health care and wellness in patients as well as the healthcare team members, (iii) Communicate the importance of teamwork in providing unbiased and inclusive patient-centered care, (iv) Discuss and clarify each profession’s scope of practice and the roles of each healthcare professions team member.

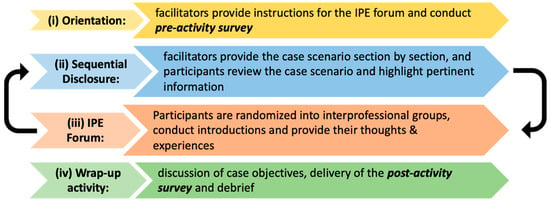

The format of the session was a four-step method of (i) Orientation: facilitators provide instructions for the IPE forum and conduct pre-activity survey; (ii) Sequential Disclosure: Facilitators provide the case scenario section by section, and participants review the case scenario and highlight pertinent information; (iii) IPE Forum: Participants are randomized into interprofessional groups and conduct introductions and provide their thoughts and experiences, throughout the sequential disclosures of the cases.; (iv) Wrap-up activity: Discussion of case objectives, delivery of the post activity survey and debrief (Figure 1). The Nova Southeastern University (NSU) Interprofessional Day (IPE Day) event was held virtually via the Zoom videoconferencing platform. The one-hour interprofessional case-based learning sequential disclosure activity (IP-CBL-SDA), was conducted virtually and hosted on the Zoom videoconferencing platform. The presenters used a PowerPoint slide set to deliver the clinical vignette to students in parts. Learners volunteered to read the sections of the case vignette aloud while the other participants followed along. Following each section of the case vignette, prompt questions were displayed for group discussion. Clinical and basic science faculty researchers facilitated the group discussions, asking guiding question and soliciting participant responses. The facilitators maintained a welcoming and safe environment to encourage participant expression of their unique views within the group discussion. Anonymous pre-and post-activity surveys were administered to learners who chose to participate in the study. The surveys were delivered using Microsoft Forms via hyperlink and a displayed QR code. The overall format was adapted from previously published methodology [16].

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the order of events in the one-hour interprofessional case-based learning sequential disclosure activity (IP-CBL-SDA) wellness training session.

The complete list of pre- and post-activity survey questions can be found in the supporting information (Supplementary S1).

Data Analysis:

Researchers analyzed anonymous data from pre-and post-activity surveys, which were linked to participant demographics including age range, year in study, gender, and discipline as described in Table 1. The questioned delivered as five-point Likert scale responses were aggregated and presented as percentages of respondents in Microsoft Excel, to convey the perceived impact of each component of the wellness session by the participants. Changes in learner attitudes were calculated as percent change in confidence, summing the “extremely confident” and “somewhat confident” values, and data was evaluated for statistical significance using unpaired student t-tests. Qualitative analysis was performed on narrative responses to deduce key themes.

3. Results

Demographic data from the responses of learners who chose to participate in the pre- and post-activity surveys is tabulated below (Table 1). Roughly a quarter each of the study participants were from the colleges of osteopathic medicine (24.6%, DO students) and pharmacy (23.4%, PharmD students), with the next largest group being from healthcare sciences (22.2%, PA, DPT, AA, and MS students), and the remainder representing dental medicine (11.1%, DMD students), optometry (8.6%, OD students), nursing (6.3%, BSN students) and allopathic medicine (3.7%, MD students) (Table 1). Nearly half of the study participants were in their first year (45.6%) with the rest being comprised of second- (30.9%) and third- (23.4%) year students; no fourth-year students participated in the study (Table 1). The majority of the study participants were between the ages of 20–25 (58%) and 26–30 (34.6%) with the rest being between 31–45 (7.4%) (Table 1). Study participants were predominantly female (67.9%) with a small faction choosing not to disclose (1.2%) (Table 1).

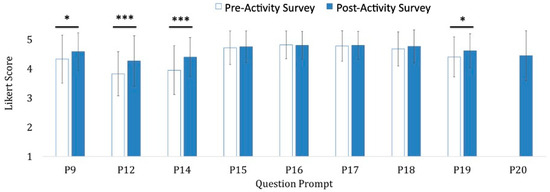

Changes in participant responses between the pre- and post-activity surveys indicate that learners gained statistically meaningful increase in their comfort and confidence level or perceived value for prompts P9, P12, P14 and P19 using Likert scale questions (Figure 2). Participants grained familiarity and increased understanding of wellness, indicated by P9: “How comfortable do you feel with your understanding of wellness?” increasing from somewhat comfortable to very comfortable (p-value < 0.05). Participants gained confidence in their ability to identify someone struggling with their wellness (P12) with an increase from somewhat confident to very confident (p-value < 0.001). Participants gained comfort in their ability to discuss and provide support to someone facing challenges with their wellness (P14) by increasing from somewhat comfortable to very comfortable (p-value < 0.001). And participants gained confidence in their ability to create an environment that fosters wellness and is a safe space to reach out for help (P19) by increasing from somewhat confident to extremely confident (p-value < 0.05). Overall students also agreed on the post-activity survey that this session provided them with resources and information that improved their understanding of wellness (P20) with an average score 4.5 (somewhat to strongly agree). Participants also showed an initial high degree of agreement that wellness IPE education and self-reflection are import, as implicated in prompts 15–18, so that while there was no significant increase from pre and post surveys, the learners already see the value of these training sessions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The participants reported a change in perception of the importance of Wellness topics. Range of significance of results of the pre-/post-activity survey responses (n = 81) to the following prompts: (P9) “How comfortable do you feel with your understanding of wellness? (P12) How confident are you in your ability to identify someone struggling with their wellness? (P14) How comfortable do you feel discussing or providing support to someone who is facing challenges with their wellness? (P15) How important is it for healthcare professional students to receive education about considering and supporting the wellness of healthcare providers, needs, and students? (P16) How important is it for healthcare professional students to receive education about considering and supporting the wellness of patients? (P17) How important is it for a healthcare provider to be able to provide information on wellness to patients, peers, and colleagues? (P18) How important is it to engage in self-reflection processes to correct implicit biases regarding wellness? (P19) How comfortable are you in your ability to create an environment that fosters wellness and is a safe space to reach out for help? (P20) Did this session provide you with resources and information that improved your understanding of wellness? Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale with 5 = Strongly Agree or Very/Extremely Comfortable/Confident/Important; 4 = Somewhat Agree/Comfortable/Confident/Important; 3 = Neutral; 2 = Somewhat Disagree/Uncomfortable/Unimportant or Minimally Confident; 1 = Strongly Disagree or Extremely Unimportant or Not at all Confident or Very Uncomfortable. Data is represented as the average response from the Likert scale +/- the standard error of the mean. * p-value < 0.05 and *** p-value < 0.001.

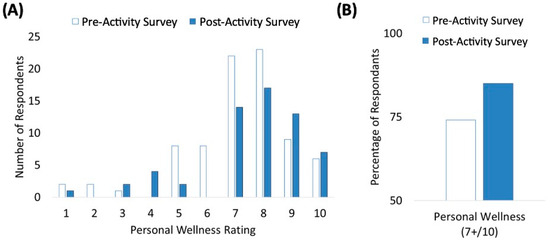

Session participants were also queried about their perception of their own wellness before and after the session (Figure 3). And while some attrition took place from the pre-activity survey to the post-activity survey, the overall trends of wellness ranking shifts to higher ratings following the session (Figure 3A). This is even more evident looking at the percentage of participants who rated their wellness between 7–10 with 10 being excellent wellness and 1 being very poor wellness (Figure 3B). The pre-activity survey showed 74% of respondents rating their wellness at or above 7 out of 10 before the session (n = 81), whereas 85% of respondents reported these higher ratings by the end of the session (n = 60) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Participant-Reported Improvement in Personal Wellness. (A) Participants rated an improvement in their personal wellness with an increase in the distribution of higher personal wellness rankings among the pre-activity survey and the post-activity survey; (B) Increased rating of individual personal wellness with 74% of respondents rated their wellness at or above 7 out of 10 before the session increasing to 85% of respondents by the end of the session, (n = 81).

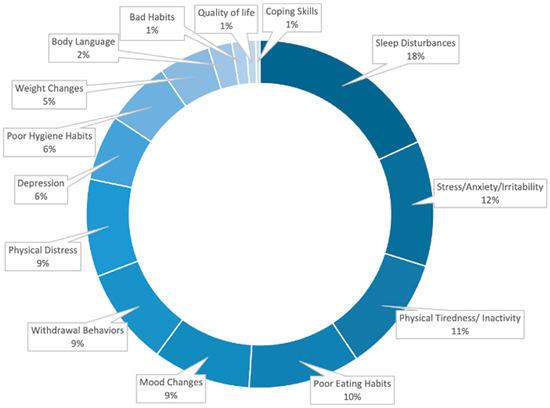

In addition to the Likert and 1–10 rating scale questions, participants were also asked to provide typed responses for the familiarity with the signs exhibited by a person struggling with their wellness during the pre-activity survey (Figure 4) as well as their feedback on the session in the post survey. Pre-activity survey prompt P11 asked “What are the 3 most prominent signs or symptoms you might notice in someone struggling with their wellness? (e.g., sleep disturbances, etc.)” and Post-activity survey prompt P11 asked “List any three Key Words/Phrases which come to your mind after this IPE activity?” For both question prompts, the participant responses were grouped for the frequency of identical or similar meaning words and presented as a percent of total input responses. The pre-activity survey prompt on signs of struggling with wellness had the responses of: Sleep Disturbances (18.2%), Stress/Anxiety/Irritability (11.7%), Physical Tiredness/ Inactivity (10.8%), Poor Eating Habits (10.4%), Mood Changes (9.1%), Withdrawal Behaviors (9.1%), Physical Distress (9.1%), Depression (6.1%), Poor Hygiene Habits (6.1%), Weight Changes (4.8%), Body Language (2.2%), Bad Habits/Indulging/Substance Abuse (1.3%), Quality of life (and 0.9%), Coping Skills (0.4%)(Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Learner identified prominent signs of struggling with wellness. Representation of common qualitative responses of the pre-activity survey (n = 240, input responses) to the following prompt: P11: What are the 3 most prominent signs or symptoms you might notice in someone struggling with their wellness? (e.g., sleep disturbances, etc.) Participants responded with free-text input responses. The frequency of identical/ similar meaning words as a percent of total input responses.

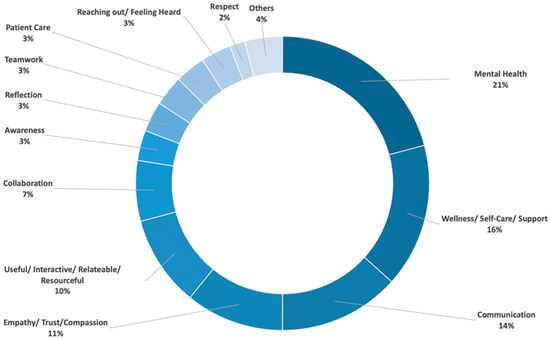

The post-activity survey prompt on takeaways had the responses of: Mental Health (21%), Wellness/Self-Care/Support (16%) and Communication (14%) being the top responses (Figure 4). Other key takeaways that learners identified from the session were Empathy/Trust/Compassion (11%), Useful/Interactive/Relatable/Resourceful (10%), Collaboration/Teamwork (10%), Awareness/Reflection (6%), Patient Care (3%), Reaching out/feeling heard (3%), Respect (2%), among other less frequently reported topics (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Key themes established through the session. Representation of common qualitative responses of the post-activity survey (n = 120, input responses) to the following prompt: P11: List any three Key Words/Phrases which come to your mind after this IPE activity? Participants responded with free-text input responses. The frequency of identical/ similar meaning words as a percent of total input responses.

Overall, the results from the pre- and post-activity surveys illustrate that while learners had some familiarity with concepts related to wellness ahead of the session, they gained valuable confidence in their abilities to understand the topic of wellness, identify someone struggling with wellness, and discuss and provide support to someone struggling with wellness. Participants collectively reported an overall boon to their own personal wellness after attending the session. Participants also indicated that they believed that the session equipped them with useful tools for understanding wellness through the use of the case and discussion focused on the interprofessional health care environment. Additionally, the majority of participants perceived the emphasis of the session to be highlighting mental health, wellness and communication, which are important components of effect interprofessional healthcare teams.

4. Discussion

Using a synchronous online network, NSU organized an annual IPE Day in 2024 that brought together eight campuses and twenty professional programs to participate, with a total of >1800 learners. IPE activities have historically been viewed as logistically laborious and challenging to execute. Our IPE exercises demonstrated that using the virtual environment helped us get beyond some of these challenges. Moreover, the session format and delivery method discussed in this manuscript can be transferable to any institution or consortium of institutions willing to collaborate.

For this study, the session format of web-based synchronous interprofessional Case Based Learning–Sequential Disclosure Activity (CBL-SDA) was well received by the students with 88% of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing that the session provided resources that improved their understanding of wellness. Following the activity, the data obtained indicates up to 47% increase (p < 0.05) in overall confidence for knowledge and comfort in ability to facilitate wellness after receiving the training (Figure 2).

Based on the cohort size for each program and accounting for the fact that the College of Healthcare Sciences provides approximately ten different healthcare professional degrees, the demographics of the participants revealed a fairly equal distribution amongst colleges. Notably, a greater proportion of study participants (~68%) were female. Additionally, about 76.6% of learners were within the first two years of their studies, demonstrating the successful implementation of this early intervention through IPE.

Participant responses were generally positive when quired on their attitude towards the importance of wellness and wellness training for health professionals and their ability to identify a person struggling with their wellness (Figure 2). Participants described prominent signs of someone struggling with their wellness as Sleep Disturbances (18.2%), Stress/Anxiety/Irritability (11.7%), Physical Tiredness/ Inactivity (10.8%), Poor Eating Habits (10.4%), Mood Changes (9.1%), Withdrawal Behaviors (9.1%), and Physical Distress (9.1%), among other signs (Figure 4). The prominence of participants identifying Sleep Disturbances as a sign may have been skewed by being provided with that language as an example in the prompt. However, taken together with the other free typed responses, participants demonstrated a solid foundational awareness of how a lack of wellness might present in colleagues, patients and themselves, ahead of the activity.

Limitations to the study include the absence of control over the group demographics, and size of the participant groups which is determined by the IPE Day administrators. Other limitations include sample size and ability to obtain longitudinal data for the outcomes of continued sessions with the learners.

The findings herein suggest that even a one-hour long activity can have significant impact on the student interest and understanding of key challenges faced by healthcare professionals pertaining to providing care with a wellness focus, as well as improving their own sense of personal wellness (Figure 3). The qualitative data gathered from pre-activity survey responses (n = 240) revealed that learners were adept at identifying key signs indicative of compromised wellness (Figure 4). Thematic analysis of the free-text responses yielded several recurrent themes. Most notably, disturbances in sleep (e.g., insomnia or hypersomnia), emotional dysregulation (e.g., increased irritability or mood swings), behavioral withdrawal (e.g., social isolation or reduced engagement in routine activities) and changes in eating habits (e.g., poor eating habits, loss of appetite) were among the most frequently reported indicators. These findings suggest that even before formal instruction or intervention, learners possess a baseline awareness of salient wellness-related concerns, likely informed by both personal experience and cultural narratives around mental health.

Results obtained from the participant input section (Figure 5) displays words/phrases including “Empathy”, “Communication”, “Support”, and others may illude to the idea that there is a need for more opportunities for training sessions of this nature in the health professions to inculcate collaboration and standardized practices to encourage wellness and a beneficial healthcare work culture. It is recommended that these opportunities are offered throughout the curriculum programs.

When combined, these findings show that the session objectives were successfully met and well received by the learners. These data also indicate that additional training and workshops of this kind are beneficial for successful IPE in the health professions, to foster teamwork, collaboration and standardized care for patients; especially with an emphasis on understanding and awareness of topics such as wellness. The results of this investigation were comparable to those of Durham et al. study, which demonstrated an increase in learner knowledge about the scope of practice of another health profession through IPE [19]. Through their study using IPE, Berger-Estilita et al. showed that learners indicated a need for an early introduction of IPE into the medical curriculum and realized that IP learning is fundamental to high-quality patient care [20]. It is important to note that IPE is useful for discussions on subjective topics such as wellness that potentially impact healthcare outcomes, such as quality of patient care, mental health, effectiveness of teams, and other emotional intelligence topics [21]. Nevertheless, despite a positive impact on learners with IPE, there is limited published research in this field, and more work is required to support intentional and planned, broad curriculum changes in healthcare professions programs [22,23]. Future studies may wish to more deeply investigate individual student perceptions of wellness, longitudinal effects and contrast differences between health care professional programs in order to gain insights that would help to create more holistic and equitable wellness interprofessional curriculum.

It can be proposed that by properly leveraging the Zoom platform and other technologies, healthcare professional programs may overcome the primary challenge faced for IPE that pertains to connecting with different programs and learners from multiple colleges/universities in different geographical regions by utilizing a web-based synchronous platform and other technologies effectively. This can potentially provide more flexible opportunities for IPE for learners.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ime4030032/s1, Supplementary S1: Data Instrument.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and K.J.C.; Methodology, S.P.; Implementation, S.P. and K.J.C.; Formal Analysis, K.J.C.; Resources, S.P.; Data Curation, S.P. and K.J.C.; Writing and Editing, S.P. and K.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study, involving human subjects was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and reviewed and exempted by the Institutional Review Board of Nova Southeastern University Institutional Review Board (IRB # 2021-12-NSU).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Elizabeth Swan* and her team for their contributions to the organization of the Interprofessional Education Day at Nova Southeastern University, and the students who participated in the activities and discussions for their candor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- National Academy of Medicine. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, M.S.; Atkinson, T.; West, C.P. Well-being in medical education: The case for change. Clin. Teach. 2020, 17, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2214–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavin, S.J.; Schindler, D.L.; Chibnall, J.T. Medical student mental health 3.0: Improving student wellness through curricular changes. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadat, H.; Lin, S.L.; Kain, Z.N. The Role of “Wellness” in Medical Education. Int. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2010, 48, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, M.L.; Slavin, S.J. Resident Wellness Matters: Optimizing Resident Education and Wellness Through the Learning Environment. Acad. Med. 2015, 90, 1246–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherak, S.J.; Rosgen, B.K.; Geddes, A.; Makuk, K.; Sudershan, S.; Peplinksi, C.; Kassam, A. Wellness in medical education: Definition and five domains for wellness among medical learners during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Med. Educ. Online 2021, 26, 1917488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argus-Calvo, B.; Clegg, D.J.; Francis, M.D.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Carrola, P.A.; Leiner, M. A holistic approach to sustain and support lifelong practices of wellness among healthcare professionals: Generating preliminary solid steps towards a culture of wellness. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, S.; Fletcher, S.; Barr, H.; Birch, I.; Boet, S.; Davies, N.; McFadyen, A.; Rivera, J.; Kitto, S. A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Med. Teach. 2016, 38, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences, and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Erwin, P.J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 388, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buring, S.M.; Bhushan, A.; Broeseker, A.; Conway, S.; Duncan-Hewitt, W.; Hansen, L.; Westberg, S. Interprofessional education: Definitions, student competencies, and guidelines for implementation. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2009, 73, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vendeloo, S.N.; Godderis, L.; Brand, P.L.P.; Verheyen, K.C.P.M.; Rowell, S.A.; Hoekstra, H. Resident burnout: Evaluating the role of the learning environment. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Future of Nursing 2020–2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; O’Malley, C.B.; DeLeon, R.; Levy, A.S.; Griffin, D.P. Inclusive LGBTQIA+ healthcare: An interprofessional case-based experience for cultural competency awareness. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 993461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, H.J.; McCarthy, S.M. Student wellness trends and interventions in medical education: A narrative review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thistlethwaite, J.E.; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay, D. The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education. A beme systematic review: Beme guide no. 23. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, e421–e444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durham, M.; Lie, D.; Lohenry, K. Interprofessional Care: An Introductory Session on the Roles of Health Professionals. MedEdPORTAL 2014, 10, 9813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger-Estilita, J.; Chiang, H.; Stricker, D.; Fuchs, A.; Greif, R.; McAleer, S. Attitudes of medical students towards interprofessional education: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eskander, J.; Rajaguru, P.P.; Greenberg, P.B. Evaluating Wellness Interventions for Resident Physicians: A Systematic Review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2021, 13, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clay, M.C.; Garr, D.; Greer, A.; Lewis, R.; Blue, A.; Evans, C. An update on the status of interprofessional education and interprofessional prevention education in U.S. academic health centers. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2018, 10, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalvo, J.L.; Sagastume, D.; Mertens, E.; Uzhova, I.; Smith, J.; Wu, J.H.; Bishop, E.; Onopa, J.; Shi, P.; Micha, R.; et al. Effectiveness of workplace wellness programmes for dietary habits, overweight, and cardiometabolic health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e648–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).