Sense of Humor in Health Sciences: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study Among First-Year Nursing Students in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Survey Measures

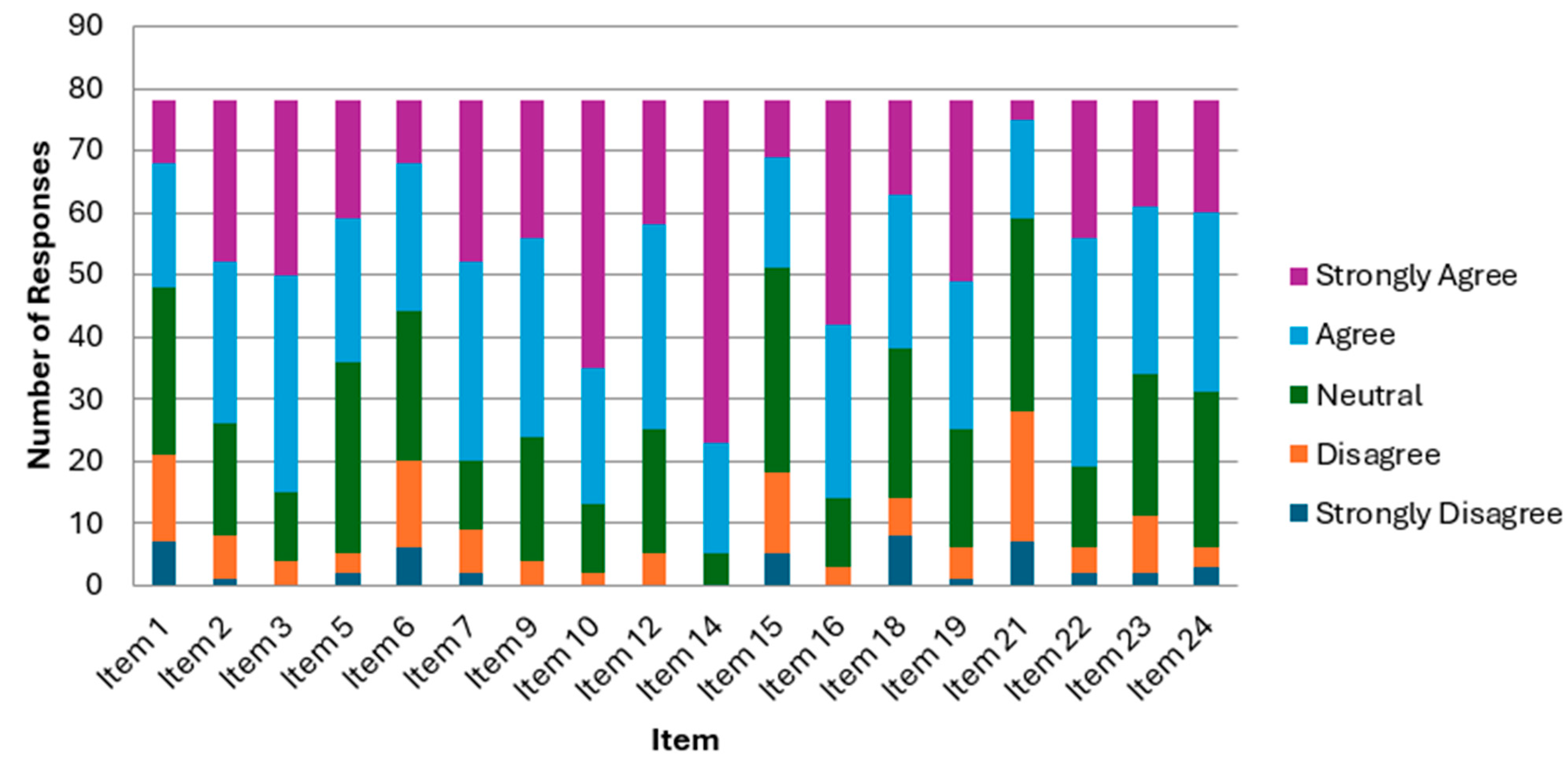

- Dimension 1 “Competence or ability to use humor”, scoring zero to 48 (items 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 23, and 24).

- Dimension 2 “Humor as a mechanism for controlling the situation”, scoring zero to 28 (items 2, 10, 14, 16, 19, 20, and 22).

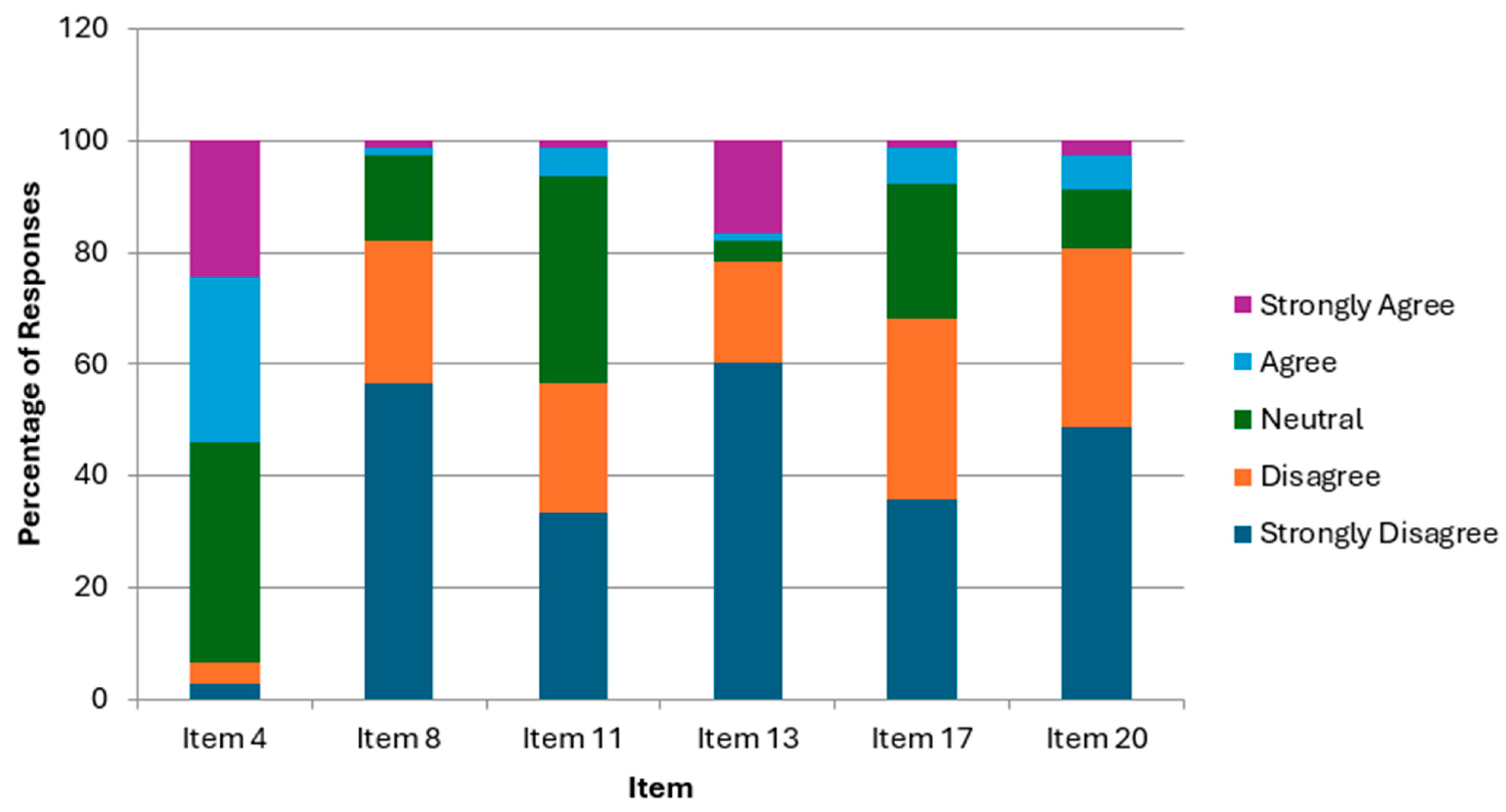

- Dimension 3 “Social evaluation and attitudes toward humor”, scoring zero to 20 (items 4, 8, 11, 13, and 17).

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El-Sayed, M.M.; AbdElhay, E.S.; Hawash, M.M.; Taha, S.M. The Power of Laughter: A Study on Humor and Creativity in Undergraduate Nursing Education in Egypt. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, S.; Jain, A.; Chaudhary, J.; Gautam, M.; Gaur, M.; Grover, S. Concept of Mental Health and Mental Well-Being, It’s Determinants and Coping Strategies. Indian J. Psychiatry 2024, 66, S231–S244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simione, L.; Gnagnarella, C. Humor Coping Reduces the Positive Relationship between Avoidance Coping Strategies and Perceived Stress: A Moderation Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarink, F.S.M.; García-Montes, J.M. Humor Interventions in Psychotherapy and Their Effect on Levels of Depression and Anxiety in Adult Clients, a Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1049476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogham, R.S.; Ali, H.F.M.; Ghaly, A.S.; Elcokany, N.M.; Seweid, M.M.; El-Ashry, A.M. Deciphering the Influence: Academic Stress and Its Role in Shaping Learning Approaches among Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Avanzi, L.; Fraccaroli, F. Emotional Demands as a Risk Factor for Mental Distress among Nurses. Med. Lav. 2014, 105, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Zhao, S.; Li, D.; Du, H. Emotional Exhaustion and Turnover Intentions among Young ICU Nurses: A Model Based on the Job Demands-Resources Theory. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartzik, M.; Bentrup, A.; Hill, S.; Bley, M.; von Hirschhausen, E.; Krause, G.; Ahaus, P.; Dahl-Dichmann, A.; Peifer, C. Care for Joy: Evaluation of a Humor Intervention and Its Effects on Stress, Flow Experience, Work Enjoyment, and Meaningfulness of Work. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 667821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydon, G.; Reis, J.; Bowen, L. The Use of Humour in Nursing Education: An Integrative Review of Research Literature. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 126, 105827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Cao, X.; Du, T. First-Year Nursing Students’ Initial Contact with the Clinical Learning Environment: Impacts on Their Empathy Levels and Perceptions of Professional Identity. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Okamura, H. Hearing Laughter Improves the Recovery Process of the Autonomic Nervous System after a Stress-Loading Task: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2018, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yue, Z. Positive Emotion Facilitates Cognitive Flexibility: An fMRI Study. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahas, V.L. Humour: A Phenomenological Study within the Context of Clinical Education. Nurse Educ. Today 1998, 18, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Huang, B.; Huang, J.; Guo, X.; Gao, T.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, W.; Yin, X.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; et al. Humor Processing and Its Relationship with Clinical Features in Patients with First-Episode Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2024, 39, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linge-Dahl, L.M.; Heintz, S.; Ruch, W.; Radbruch, L. Humor Assessment and Interventions in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimbekov, N.S.; Razzaque, M.S. Laughter Therapy: A Humor-Induced Hormonal Intervention to Reduce Stress and Anxiety. Curr. Res. Physiol. 2021, 4, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.M.M.; Marques-Vieira, C.M.A.; Antunes, A.V.; Frade, M.D.F.G.; Severino, S.P.S.; Valentim, O.S. Humor Intervention in the Nurse-Patient Interaction. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2019, 72, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartzou, E.; Tsiloni, E.; Mantzoukas, S.; Dragioti, E.; Gouva, M. Humor and Quality of Life in Adults with Chronic Diseases: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e55201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelly, F.; Kacem, I.; Moussa, A.; Ghenim, A.; Krifa, I.; Methamem, F.; Chouachane, A.; Aloui, A.; Brahem, A.; Kalboussi, H.; et al. Healing Humor: The Use of Humor in the Nurse-Patient Relationship. Occup. Dis. Environ. Med. 2022, 10, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorson, J.A.; Powell, F.C. Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Sense of Humor Scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1993, 49, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbelo-Baquero, B.; Alonso-Rodriguez, M.C.; Valero-Garces, C.; Thorson, J.A. A Study of Sense of Humor in Spanish and American Samples. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2006, 8, 447–454. [Google Scholar]

- López Martínez, O.; Sevilla Moreno, A.; Velandrino Nicolás, A.P. Fortalezas Positivas: El Sentido Del Humor En Alumnos Universitarios. INFAD 2010, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara-Manzanares, J.; Quintana, S.M.; García-Morís, R.; Serrano, M.J.L. The Uses of Humour in Spanish Environmental Education: An Exploratory Qualitative Analysis of the Potentialities, Limitations and Good Practices of Humour. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2024, 40, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Guerrero-Barona, E.; Chambel, M.J.; Guerrero-Molina, M.; González-Rico, P. Predictor Variables of Mental Health in Spanish University Students. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1367–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, M.I.; Rothbart, M.K. Research on Attention Networks as a Model for the Integration of Psychological Science. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.C.; Echeverri, L.F.; Londoño, M.J.; Ochoa, S.A.; Quiroz, A.F.; Romero, C.R.; Ruiz, J.O. Effects of a Humor Therapy Program on Stress Levels in Pediatric Inpatients. Hosp. Pediatr. 2017, 7, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, C.K.; Leitao, C.B. Laughter as Medicine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventional Studies Evaluating the Impact of Spontaneous Laughter on Cortisol Levels. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visier-Alfonso, M.E.; Sarabia-Cobo, C.; Cobo-Cuenca, A.I.; Nieto-López, M.; López-Honrubia, R.; Bartolomé-Gutiérrez, R.; Alconero-Camarero, A.R.; González-López, J.R. Stress, Mental Health, and Protective Factors in Nursing Students: An Observational Study. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 139, 106258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de España Series Históricas de Estudiantes Universitarios Desde El Curso 1985–1986. Total SUE 2023. Available online: https://estadisticas.universidades.gob.es/dynPx/inebase/index.htm?file=pcaxis&l=s0&path=/Universitaria/Alumnado/EEU_2023/Serie/TotalSUE/&type=pcaxis (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauvet, S.; Hofmeyer, A. Humor as a Facilitative Style in Problem-Based Learning Environments for Nursing Students. Nurse Educ. Today 2007, 27, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.; Singh, U.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. Descriptive Statistics and Normality Tests for Statistical Data. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.T.; DuBose, L.; Arunachalam, P.; Hairrell, A.S.; Milman, R.M.; Carpenter, R.O. The Effects of Humor in Clinical Settings on Medical Trainees and the Implications for Medical Educators: A Scoping Review. Med. Sci. Educ. 2023, 33, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mireault, G.C.; Crockenberg, S.C.; Heilman, K.; Sparrow, J.E.; Cousineau, K.; Rainville, B. Social, Cognitive, and Physiological Aspects of Humour Perception from 4 to 8 Months: Two Longitudinal Studies. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 36, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Fan, S.; Chen, D.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, W. The Relation between Humor Styles and Nurse Burnout: A Cross-Sectional Study in China. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1414871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Chen, T. Clown Care in the Clinical Nursing of Children: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1324283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, E.; Papastavrou Brooks, C.; Chawner, D.; Foye, U.; Declercq, D.; Brooks, H. “Beyond Laughter”: A Systematic Review to Understand How Interventions Utilise Comedy for Individuals Experiencing Mental Health Problems. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1161703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagalidou, N.; Baier, J.; Laireiter, A.-R. The Effects of Three Positive Psychology Interventions Using Online Diaries: A Randomized-Placebo Controlled Trial. Internet Interv. 2019, 17, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.H.I.; Bardaie, N.I. Utilization of Humor and Application of Learning Theory: Perspective of Nursing Students. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 126, 105837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, K.; Sivaramakrishnan, G. Therapeutic Clowns in Pediatrics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2016, 175, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, J.; O’Malley, M.; McCarthy, K. How Do Mental Health Professionals Use Humor? A Systematic Review. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2024, 19, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñar-Rodríguez, S.; Rodríguez-Martín, D.; Corcoles-Martínez, D.; Tolosa-Merlos, D.; Leñero-Cirujano, M.; Puig-Llobet, M. Correlational Study on the Sense of Humor and Positive Mental Health in Mental Health Professionals. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1445901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schall, S.A.; Martin, L.A.; Kernes, J.L.; Powers, C. Humor Styles Moderate the Association between Health Difficulties and Quality of Life in Individuals Diagnosed with a Chronic Disease. Humor 2025, 38, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkelson, C.; Keiser, M.; Yorke, A.M.; Smith, L. Piloting a Multifaceted Interprofessional Education Program to Improve Physical Therapy and Nursing Students’ Communication and Teamwork Skills. J. Acute Care Phys. Ther. 2018, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godino-Iáñez, M.J.; Martos-Cabrera, M.B.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Vargas-Román, K.; Membrive-Jiménez, M.J.; Albendín-García, L. Play Therapy as an Intervention in Hospitalized Children: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age (Years) | n = 78 |

|---|---|

| <19 | 30 (38.5%) |

| 19–24 | 39 (50.0%) |

| >24 | 9 (11.5%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 69 (88.5%) |

| Male | 9 (11.5%) |

| Employment status | |

| Student only | 63 (80.8%) |

| Student with part-time employment | 9 (11.5%) |

| Student with full-time employment | 6 (7.7%) |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 9 | 46 | 30.68 (8.730) | 0.914 |

| D2 | 11 | 28 | 22.24 (4.039) | 0.770 |

| D3 | 8 | 20 | 13.91 (2.920) | 0.604 |

| Overall | 34 | 90 | 66.83 (13.064) | 0.907 |

| Age (Years) | D1 | D2 | D3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Correlation coefficient | -- | |||

| Sig. (two-tailed) | . | ||||

| D1 | Correlation coefficient | 0.032 | -- | ||

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.783 | . | |||

| D2 | Correlation coefficient | 0.045 | 0.547 ** | -- | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.694 | <0.001 | . | ||

| D3 | Correlation coefficient | 0.109 | 0.333 ** | 0.561 ** | -- |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.344 | 0.003 | <0.001 | . |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-León, P.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Garrido-Bueno, M.; Romero-Castillo, R. Sense of Humor in Health Sciences: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study Among First-Year Nursing Students in Spain. Int. Med. Educ. 2025, 4, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4030029

Fernández-León P, Fagundo-Rivera J, Garrido-Bueno M, Romero-Castillo R. Sense of Humor in Health Sciences: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study Among First-Year Nursing Students in Spain. International Medical Education. 2025; 4(3):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4030029

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-León, Pablo, Javier Fagundo-Rivera, Miguel Garrido-Bueno, and Rocío Romero-Castillo. 2025. "Sense of Humor in Health Sciences: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study Among First-Year Nursing Students in Spain" International Medical Education 4, no. 3: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4030029

APA StyleFernández-León, P., Fagundo-Rivera, J., Garrido-Bueno, M., & Romero-Castillo, R. (2025). Sense of Humor in Health Sciences: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study Among First-Year Nursing Students in Spain. International Medical Education, 4(3), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4030029