Abstract

The objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) is a well-established tool for assessing clinical skills, providing reliability, validity, and generalizability for high-stakes examinations. Des Moines University College of Osteopathic Medicine (DMU-COM) adapted the OSCE for formative assessments in undergraduate medical education, focusing on interpersonal aspects in the primary care setting. Students are graded by standardized patients and faculty observers on interpersonal skills, history/physical examination, oral case presentation, and documentation. The purpose of the study is to establish the reliability and to identify sources of variation in the DMU-COM OSCE to aid medical educators in their understanding of the accuracy of clinical skills. We examined student performance data across five OSCE domains. We assessed intra- and inter-OSCE reliability by calculating KR20 values, determined sources of variation by multivariate regression analysis, and described relationships among observed variables through factor analysis. The results indicate that the OSCE captures student performance in three dimensions with low intra-OSCE reliability but acceptable longitudinal inter-OSCE reliability. Variance analysis shows significant measurement error in rubric-graded scores but negligible error in checklist-graded portions. Physical exam scores from patients and faculty showed no correlation, indicating value in having two different observers. We conclude that a series of formative OSCEs is a valid tool for assessing clinical skills in preclinical medical students. However, the low intra-assessment reliability cautions against using a single OSCE for summative clinical skills competency assessments.

1. Introduction

The assessment of clinical skills is a key component of the foundational phase of physician training prior to graduating from medical school (undergraduate medical education, UME). In these clinical performance evaluations, students complete a series of tasks in a patient encounter and are being evaluated by trained observers [1]. An objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) is a time-tested standardized format for the assessment of clinical skills based on a structured encounter with a simulated patient that is designed to evaluate if a candidate knows how to perform a variety of clinical tasks [2,3]. An OSCE consists of several stations, each evaluating a separate, well-defined clinical skill that is graded using predetermined criteria. Objectivity is achieved by ensuring that all examinees complete the same set of tasks and are graded using standards set by a panel of content experts. OSCEs stations are structured to give a comprehensive overview of examinee performance across the clinical performance domains of consultation, examination, and procedures [4]. A well-designed OSCE is characterized by reliability, validity, acceptability, affordability, and educational impact—criteria that require extensive planning, thorough psychometric analysis, and broad stakeholder participation in standard-setting [5].

A major concern for using an OSCE as a basis for defensible grading or pass/fail decisions is the reliability of the assessment, which is determined by the number of stations, total testing time and—to a minor extent—the number of observers [4]. To attain satisfactory reliability and generalizability, OSCEs require a minimum of 10–12 stations and might be conducted over several days [6,7,8]. It deserves to be noted that even if OSCEs are a reliable and generalizable assessment that add value to a comprehensive system of clinical skills assessment [9], they are not perfect as they require enormous resources, occur in an artificial setting without real patients, and rely on the deconstruction of a complex clinical encounter into smaller individual tasks [10,11,12].

At our institution (Des Moines University–College of Osteopathic Medicine, DMU-COM), the OSCE format has been adapted to enable its use as a tool for formative assessment during the preclinical phase of education and as part of a comprehensive clinical skills assessment in the clinical phase. Neither of these uses strictly meets the established criteria for OSCEs in terms of numbers of stations, observers, and total examination time [6], which means that the assessments can only provide supporting evidence for clinical competency and cannot be used as a stand-alone assessment. At DMU-COM, students are introduced to the concept of OSCE as part of the Clinical Medicine courses (clinically focused courses that develop students’ foundational diagnostic and procedural skills through lectures, case-based learning, simulations, and mentored patient encounters, emphasizing history-taking, physical exams, and clinical reasoning). In the preclinical phase of the curriculum, students complete seven formative standardized simulated patient encounters that are modeled after the OSCE format, and an eighth examination follows during a comprehensive clinical assessment after the first clerkship year. The DMU-COM OSCE does not include an evaluation of procedural skills since those are evaluated in parallel clinical medicine laboratories. Students are evaluated by the standardized patient and by a faculty observer using a rubric for the interpersonal aspects of the patient interactions and checklists for the technical criteria of the examination, oral presentation, and clinical documentation. Students are given feedback on their performance and are afforded the opportunity to repeat the encounter if the criteria for a passing grade are not met. Finally, the class meets for a mandatory large group debriefing session. With its focus on the patient experience and its formative nature, the DMU-COM OSCE thus incorporates key principles of osteopathic medical education by emphasizing patient-centered primary care [13]. To highlight the differences between the DMU-COM format and the standardized OSCE framework, the exercise is referred to in curricular materials as objective structured clinical experience or encounter (rather than examination).

Assessment of clinical skills via OSCE is a complex task, and an assessment of the quality of the OSCE requires the careful monitoring of multiple performance measures [14]. The present study was undertaken to determine the reliability and generalizability of the DMU-COM OSCE to justify the utilization of this method for formative assessment in undergraduate medical education. The objective of this research is to determine if the abbreviated four-station two-observer OSCE format provides sufficient reliability to certify clinical competency of students at the end of the preclinical curriculum. We hypothesize that, while the shorter OSCE will show lower reliability than the established full 12-station format, the aggregate of OSCE performance over 2 years of preclinical education will show sufficient reliability to justify decisions about students’ clinical competence. This study thus fills an important gap in our knowledge on clinical competency assessments on the individual school level—information that has become more urgent since clinical skills assessments have been discontinued at the national level and the responsibility of clinical skills competency assurance now falls to individual US Medical Schools [15,16]. We hypothesize that the DMU-COM OSCE curriculum provides sufficient longitudinal reliability to contribute value to a comprehensive clinical skills assessment program.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. OSCE Format

In DMU-COM preclinical DO curriculum, students are assessed with 7 OSCEs spaced out over 4 semesters. The preclinical phase of the DMU curriculum consists of four semesters of instruction in foundational sciences, clinical sciences and practical clinical skills. The preclinical phase ends with students taking the first step of the US medical licensing exams, and upon successful passing of the exams, student progress to the 2-year clinical clerkship phase of undergraduate medical education. In each of the preclinical semesters, students take a Clinical Medicine course, during which they are taught essential clinical skills in patient interviewing, physical examination, clinical reasoning and documentation of patient encounters. Each of the four Clinical Medicine courses features two OSCE encounters. The first OSCE is an orientation to the format and is not scored, which leaves a total of seven OSCE to be included in this study. Another OSCE follows the first clerkship year, but it is not included in this analysis due to significant differences in grading. The patient presentation of the OSCE is coordinated with the concurrent lecture curriculum (i.e., SP presenting with shortness of breath during the cardiology/respiratory/hematology block of clinical sciences). The assessment features four distinct tasks: elicit a patient history, conduct a physical examination, deliver an oral presentation, and document the encounter in a note outlining subjective and objective information, assessment, and plan (SOAP). The assessment does not include a test of procedural skills, which are instead determined in separate clinical skills laboratory sessions. Student performance is graded by the standardized patient (SP) and a faculty observer (FO). SPs rate students’ interpersonal, professional, and physical examination skills using a 5-point rubric (Table 1; for examples of checklists and rubrics see Supplementary Material). In addition, SPs grade the technical elements of the physical examination with a checklist. The FOs rate physical examination, oral presentation, and SOAP note using a checklist. Since the number of checklist items for physical examination varies widely between OSCEs, non-checklist fraction of the grade related to interpersonal skills ranges between 2.3 and 23% (average 7.3%). The OSCE is completed with a self-assessment of students’ performance not included as part of the grade. OSCEs were designed, administered, and monitored by MB and SP. Students are given faculty feedback on their performance and attend a mandatory debriefing session. A score of greater than 3/5 on the interpersonal skills rubric and greater than 70% on the checklist assessment are required to pass the OSCE; failures are remediated by re-taking the OSCE in question with a different SP.

Table 1.

Standardized patient rubric for evaluation of interpersonal and professional skills.

2.2. Study Population

Data from students of the DO24-DO26 cohorts in the preclinical phase of the curriculum (AY2021/22 to 2023/24) were used for the analysis (inclusion criterion: member of the osteopathic medical student cohorts DO24, DO25 or DO26; exclusion criterion: students with incomplete OSCE records). 103 standardized patients participated in the assessments.

2.3. Analysis of Intra- and Inter-Assessment Reliability and Factors

Intra-OSCE reliability: For each assessment, the reliability of the sub-scores on the domains of interpersonal skills, physical examination, and SOAP note was determined using Cronbach’s alpha [17] (all data analyses conducted by MS; SPSS ver. 29, Chicago, IL, USA). Depending on the operational details of each OSCE, up to 5 FO scores of students’ oral presentation and physical examination were included in the reliability study for 3–9 sub-scores per OSCE. After Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s tests showed suitability of the data for factor analysis (KMO score of 0.72 and Bartletts test significance of <0.001, respectively), an exploratory factor analysis was performed on the 9 sub-scores of the Year 2 Capstone OSCE (Extraction: Principal components, Eigenvalue > 1, Varimax rotation, cutoff 0.5; SPSS).

Analysis of inter-assessment reliability: Data from the 2021–2024 OSCEs were tabulated to track the longitudinal performance of the DO24-DO26 classes in the categories of 1. Interpersonal skills 2. History and physical examination, 3. Professionalism, 4. SOAP note, 5. the likelihood of the patient returning to the provider and 6. the final grade. After removal of incomplete records, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated on the matrix of 594 students × 7 OSCEs (SPSS).

2.4. Analysis of Variance

To assess the variance in the SP-scored items, SPs and students were assigned a unique identifier (594 students, 103 SPs, 4450 encounters), and the sex of students and SPs were coded. Variance of student grades was analyzed for ratings (as dependent variable) of interpersonal skills, professionalism, history/physical (rubric), the likelihood of return to the provider, and the checklist-graded evaluation of the physical examination with the general linear regression model (SPSS). The analysis examined the influence of the student, the SP, the position of the OSCE in the curriculum, and the sex match between student and SP as random factors.

3. Results

3.1. Participation

Data from 594 students (and 103 standardized patients) were included in the study.

3.2. Grade Trends and Difficulty

The checklist evaluations of the physical examination (FO and SP) and the FO evaluation of history taking showed positive trends and improvement in over 2/3 of students. Class average grades remained steady over the 7 preclinical OSCE in all other grading criteria (Table 2).

Table 2.

Grade trends over the 7 preclinical OSCE.

3.3. Intra- and Inter-OSCE Reliability and Factors

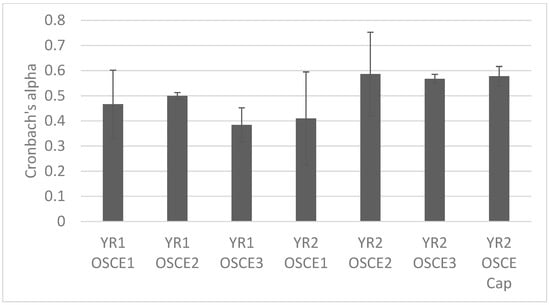

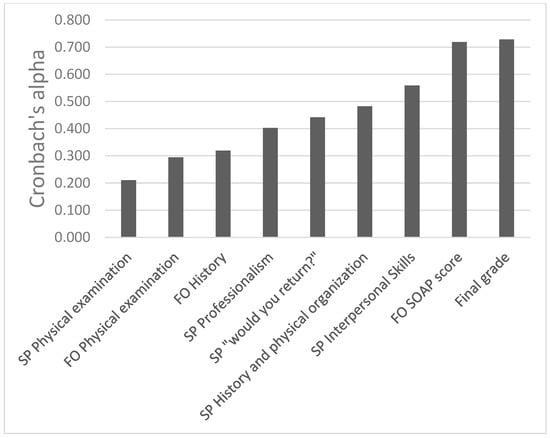

The intra-assessment reliability over 3 years (i.e., correlation of the 3–9 sub-scores within one OSCE) varied between 0.38 and 0.59, with an average of 0.5 (Figure 1). The inter-OSCE reliability (i.e., correlation of the sub-scores over the 7 preclinical OSCEs) of the final grade for the 7-assessements on the preclinical curriculum showed a reliability of 0.7, with the most reliable grading component being the FO-scored SOAP note (Figure 2). The factor analysis of the 9 grading components of the Capstone OSCE identified 3 clearly separable dimensions of the examination which can be defined as patient perception, conducting and summarizing an examination, and formulating an assessment/plan (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Intra-OSCE reliability of grading components related to patient experience, history, physical examination, oral presentation, and documentation. Depending on the assessment, 3–9 components contribute to the grade.

Figure 2.

Inter-OSCE reliability of scores and sub-scores DO24-DO26. The SOAP note score shows the best reliability of the grading components (0.719); the reliability of the final grade is 0.728.

Table 3.

Factor analysis of Capstone OSCE.

3.4. Inter-Rater Reliability

On 14 occasions, SP and FO both evaluated students’ physical examination skills using a checklist. The inter-rater correlation of these assessments varied between −0.04 and 0.51 (average 0.14, classified as “small”).

3.5. Sources of Variance in SP-Graded Criteria

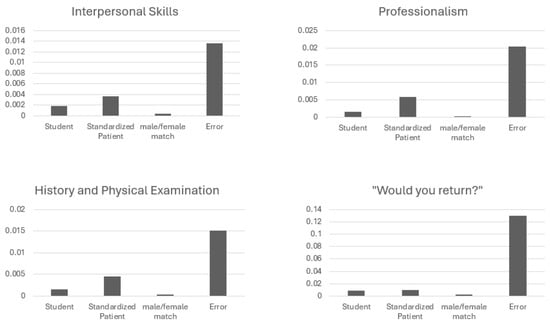

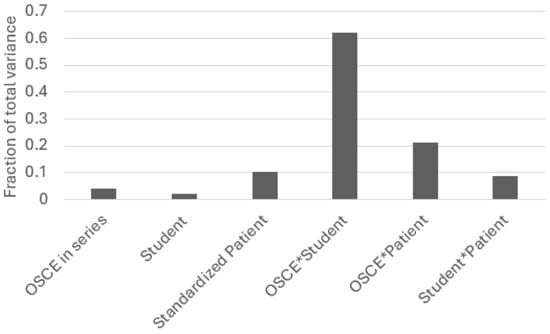

Most of the variance in the rubric-graded SP observations remains unaccounted by any of the 4 examined factors (SP, Student, number of OSCE, and SP/Student sex match) and is classified as a random error of measurement. Of the examined factors, the SP is the largest source of variance, eclipsing the variance ascribed to the examinee (Figure 3). The variation in the checklist-graded assessment of the physical examination depends most strongly on the combination of student and OSCE, with no significant variance arising from experimental error (Figure 4). The sex match between SP and student did not influence the scores for any of the examined dependent variables.

Figure 3.

Sources of variance for the SP-rubrics on students’ interpersonal skills, professionalism, history and physical examination, and the concluding question if the patient would return to this provider. Note that most of the variance for each dependent variable is random error. In each case, the SP contributes more to the remaining variance than the examinee (student).

Figure 4.

Sources of variation for the SP checklist grade of the physical examination. The bulk of the variation is explained by the combination of the student and the OSCE. The SP only plays a minor role, and the random error measurement is minimal.

4. Discussion

At DMU-COM, simulated patient encounters were first introduced in 1996. These encounters were designed as formative assessments with an emphasis on capturing the patient experience, allowing for individualized faculty feedback, inviting self-reflection, holding a formal debriefing, and providing opportunities for immediate remediation of deficiencies. In designing the assessment, the college emphasized SP feedback on examinees’ interpersonal skills and empathy to further its mission of training physicians for patient-centered, compassionate care. The demonstration of procedural skills was deliberately omitted as these aspects of clinical competency are assessed elsewhere in the curriculum. With the emphasis on interpersonal skills and empathy, the college sought to adapt the OSCE model for the use in osteopathic medical education and the training of primary care providers that has long been the mission of the osteopathic profession [18].

As the assessment tools expanded, the simulation sessions gained key characteristics of the time-tested OSCE format [2] but did not meet the established stringent criteria in terms of station numbers, multiple observers, and total time of examination [8]. The grading elements of history, physical examination, oral presentation, and documentation classify the DMU-COM assessment as a four-station OSCE. With the understanding that this assessment would not strictly fit the criteria for high-stakes, summative OSCEs, the college nevertheless adopted the name OSCE for the exercise (but referring to the exercise as experience or encounter in curricular material). The present study was undertaken to assess reliability and sources of variation of the DMU-COM OSCE, with the ultimate goal of estimating the value of these assessments for the certification of clinical skills. Data collection for the present study began in 2021 after the COVID restrictions on in-person instruction were lifted.

Our analysis shows that the observations of physical examination and history-taking show a clear improvement over the course of the preclinical curriculum, indicating that students are progressing in the more technical skills of encounter. By contrast, students’ interpersonal skills and professionalism ratings show little change over the same time period. This might be due in part to the notorious difficulties in measuring communication skills with an OSCE [19], but also suggests that interpersonal aspects of the patient encounter develop differently than purely technical skills. While it is possible to advance communication skills through teaching in the simulated setting [20], there is also clear evidence that without practice, communication skills deteriorate over time [21]. The observed stagnation might reflect a balance of these forces.

The intra-assessment reliability of the DMU-COM OSCE sub-scores varies between different assessments but in no case exceeds 0.59—well in line with similar 4-station OSCEs conducted at other institutions [6,8] but falling short of the generally accepted threshold of reliability for stand-alone assessments of 0.7 [22]. A factor analysis shows that the DMU-COM OSCE has multiple dimensions. The grading items in the scale load onto three separate factors, indicating that the assessment measures three distinct skills–a structure that can be expected to result in low reliability [22]. Our data also show that some OSCE grading components show remarkable inter-assessment reliability over the course of the preclinical curriculum. The faculty-graded SOAP note component and the overall grade both have alpha values above 0.7, which supports the use of a series of OSCEs as an integral part of a robust clinical competency assessment.

A key element of the OSCE–the physical examination–is evaluated by two independent raters: the standardized patient and a faculty observer who watches a recording of the encounter. Both ratings show low inter-OSCE reliability, and the correlation between these ratings is generally poor. This is likely caused by faculty and patients having profoundly different perspectives on the exam. The fact that observers have different viewing angles (first person experience vs. observer behind video screen) might be just as important as the different criteria of patient and experienced physician (i.e., if it feels correct to a lay person vs. if it looks correct to an expert) [23,24]. This finding highlights the importance of engaging two observers who each provide unique aspects to this critical part of the assessment.

A known weakness of the OSCE is the subjectivity of the examiner that can result in a high variability of the score [25,26]. To examine the observer-dependent variance of the DMU-COM OSCE scores, we coded each encounter with a unique standardized patient identifier and categorized the sex match between student and patient. We found that while the identity of the patient contributed very little to the rubric-scored assessments of interpersonal skills, the patient-dependent variation nevertheless eclipsed the student-factor. This finding is somewhat surprising, as it suggests that the scores of students’ interpersonal skills do not most strongly depend on the student but are largely determined by statistical error and the patient. In contrast, the checklist-graded patient evaluation of students’ physical examination skills has only negligible error and depends most strongly on the student and the task. We explain this discrepancy with the greater subjectivity of rubric-grading compared to checklists [27]. However, since the patient rubrics provide valuable information on the patient experience, the OSCE clearly benefits from cautious inclusion of these scores.

The main limitation of this study design lies in its inability to show the predictive value of the clinical competence measurements. While the study shows the reliability and construct validity of the OSCEs in the preclinical phase of the curriculum (years 1 and 2), it does not show how well the OSCE assessments predict clinical performance in the clerkship phase of UME (years 3 and 4). More research on the correlation of OSCE performance with clerkship preceptor evaluations and other clinical performance measures could shed light on the predictive power of the OSCE assessments of clinical and interpersonal skills.

5. Conclusions

While not a perfect measurement of clinical competency, the OSCE clearly adds value to a system of competency assessments that ideally includes a broad spectrum of workplace- and laboratory-based assessments. The variant of the OSCE practiced at DMU-COM, with its key features of formative feedback and the focus on the patient experience, does not achieve sufficient intra-assessment reliability to serve as a sole criterion for summative evaluation. However, the reliability of the DMU-COM OSCE compares well with the reliability of similar OSCEs at other institutions, and we conclude that final grades of the OSCE protocol described in this study have sufficient inter-assessment reliability to support a clinical competency evaluation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ime4030025/s1, Figure S1: Faculty observer and standardized patient grading documents

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S., S.P. and M.B.; methodology, M.S.; software, M.S.; validation, M.S.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.S.; resources, M.S.; data curation, M.S. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S., S.P. and M.B.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was granted exempt status by the DMU IRB (IRB-2023-24). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Des Moines University (IRB-2023-24 on 7/25/23).

Informed Consent Statement

Consent was not required due to the use of anonymized data.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Fran Smith-Fatten for technical support. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Microsoft Copilot (version 4/25) for the purposes of creating the abstract. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DMU-COM | Des Moines University–College of Osteopathic Medicine |

| FO | Faculty observer |

| OSCE | Objective structured clinical examination |

| SP | Standardized patient |

| SOAP | Subjective, objective, assessment, plan (format for documentation) |

References

- John, J.T.; Gowda, D.; Schlair, S.; Hojsak, J.; Milan, F.; Auerbach, L. After the Discontinuation of Step 2 CS: A Collaborative Statement from the Directors of Clinical Skills Education (DOCS). Teach. Learn. Med. 2023, 35, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, R.M.; Stevenson, M.; Downie, W.W.; Wilson, G.M. Assessment of clinical competence using objective structured examination. Br. Med. J. 1975, 1, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.E. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad. Med. 1990, 65, S63–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.Z.; Ramachandran, S.; Gaunt, K.; Pushkar, P. The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE): AMEE Guide No. 81. Part I: An historical and theoretical perspective. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, e1437–e1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vleuten, C.P. The assessment of professional competence: Developments, research and practical implications. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 1996, 1, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannick, M.T.; Erol-Korkmaz, H.T.; Prewett, M. A systematic review of the reliability of objective structured clinical examination scores. Med. Educ. 2011, 45, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, D.B.; Norman, G.R.; Linn, R.L. Performance-Based Assessment: Lessons From the Health Professions. Educ. Res. 1995, 24, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Luo, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, L.; Tan, S. Impact of station number and duration time per station on the reliability of Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) scores: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boursicot, K.; Etheridge, L.; Setna, Z.; Sturrock, A.; Ker, J.; Smee, S.; Sambandam, E. Performance in assessment: Consensus statement and recommendations from the Ottawa conference. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malau-Aduli, B.S.; Jones, K.; Saad, S.; Richmond, C. Has the OSCE Met Its Final Demise? Rebalancing Clinical Assessment Approaches in the Peri-Pandemic World. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 825502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelland, L.; Kolomitro, K.; Hopkins-Rosseel, D.; Durando, P. The Scientific Rigor of the Objective Structured Examination for Competency Assessment in Health Sciences Education: A Systematic Review. J. Phys. Ther. Educ. 2022, 36, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo-Rivera, S.; Fuenzalida-Muñoz, B.; Vicencio-Clarke, S.; Elbers-Arce, A.; Bozzo-Navarrete, S.; Kunakov, N.; Miranda-Hurtado, C.; Shibao-Miyasato, H.; Sanhueza, J.; Cornejo, C.; et al. Advancing the assessment of clinical competence in Latin America: A scoping review of OSCE implementation and challenges in resource-limited settings. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.S.; Clark-Chiarelli, N.; Block, S.D. Comparison of osteopathic and allopathic medical Schools’ support for primary care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1999, 14, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pell, G.; Fuller, R.; Homer, M.; Roberts, T. How to measure the quality of the OSCE: A review of metrics—AMEE guide no. 49. Med. Teach. 2010, 32, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achike, F.I.; Christner, J.G.; Gibson, J.L.; Milman, R.M.; Obadia, S.; Waer, A.L.; Watson, P.K. Demise of the USMLE Step-2 CS exam: Rationalizing a way forward. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2023, 115, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsufrakis, P.J.; Chaudhry, H.J. Evolution of Clinical Skills Assessment in the USMLE: Looking to the Future After Step 2 CS Discontinuation. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 1236–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, B.; Florentine, P. The OSCE in a pre-registration osteopathy program: Introduction and psychometric properties. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2013, 16, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piumatti, G.; Cerutti, B.; Perron, N.J. Assessing communication skills during OSCE: Need for integrated psychometric approaches. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosméan, L.; Chaffanjon, P.; Bellier, A. Impact of physician–patient relationship training on medical students’ interpersonal skills during simulated medical consultations: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensing, M.; Jung, H.P.; Mainz, J.; Olesen, F.; Grol, R. A systematic review of the literature on patient priorities for general practice care. Part 1: Description of the research domain. Social Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1573–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortina, J.M. What Is Coefficient Alpha? An Examination of Theory and Applications; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; Volume 78, pp. 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, J.M.; Vardaxis, V.; Anwar, N.; Hagenbucher, J. Relationship Between Faculty and Standardized Patient Assessment Scores of Podiatric Medical Students During a Standardized Performance Assessment Laboratory. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2016, 106, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, J.M.; Vardaxis, V.; Anwar, N.; Hagenbucher, J. Differences in Faculty and Standardized Patient Scores on Professionalism for Second-Year Podiatric Medical Students During a Standardized Simulated Patient Encounter. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2018, 108, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleicher, I.; Leitner, K.; Juenger, J.; Moeltner, A.; Ruesseler, M.; Bender, B.; Sterz, J.; Schuettler, K.-F.; Koenig, S.; Kreuder, J.G. Examiner effect on the objective structured clinical exam—A study at five medical schools. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haviari, S.; de Tymowski, C.; Burnichon, N.; Lemogne, C.; Flamant, M.; Ruszniewski, P.; Bensaadi, S.; Mercier, G.; Hamaoui, H.; Mirault, T.; et al. Measuring and correcting staff variability in large-scale OSCEs. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yune, S.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Im, S.J.; Kam, B.S.; Baek, S.Y. Holistic rubric vs. analytic rubric for measuring clinical performance levels in medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).