Faculty Reflections About Participating in International Medical School Curriculum Development, a Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

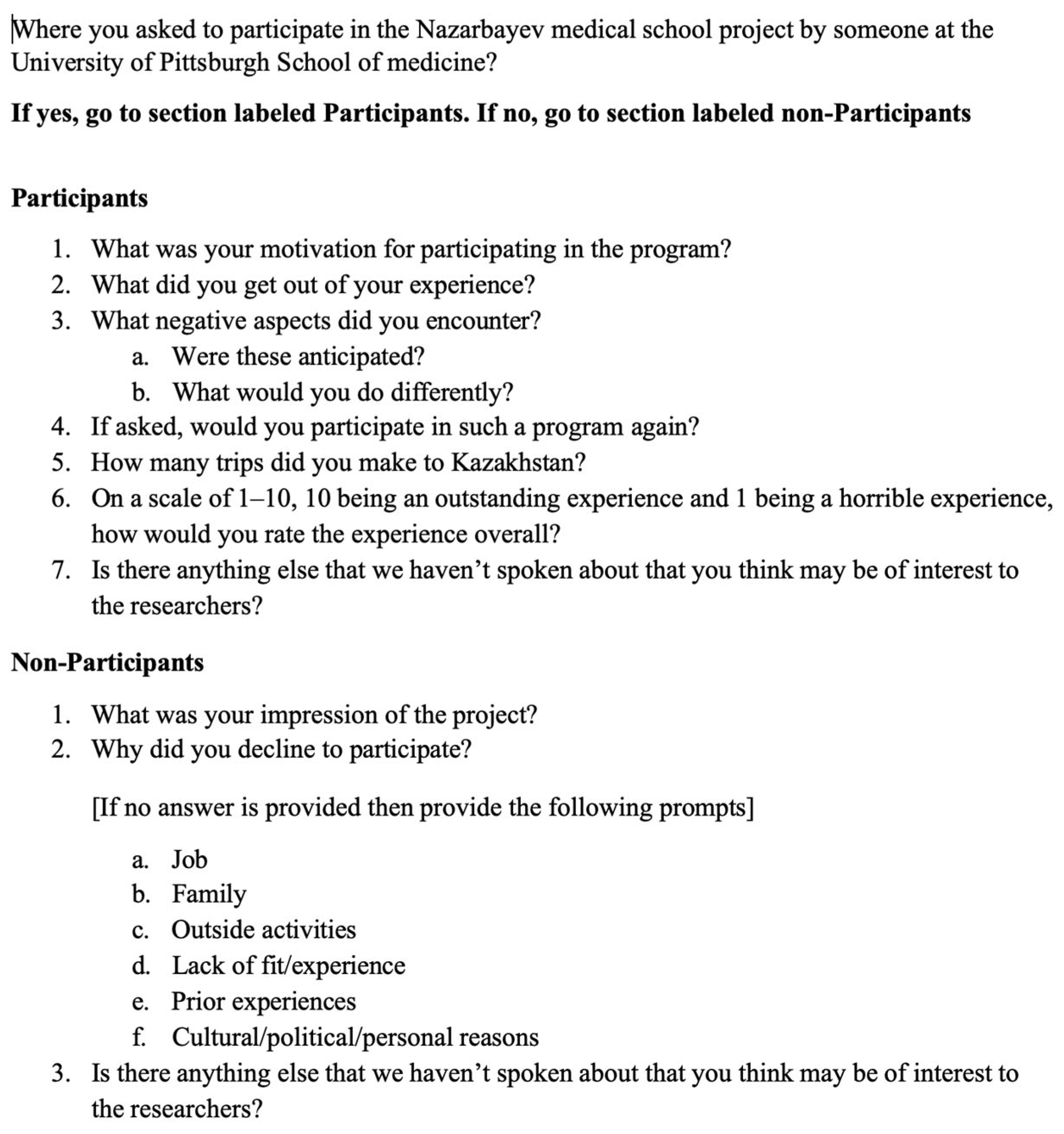

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

…Actually, in going through our <slides>, we used the same sort of pretty intense scrutiny to go over our material and say this doesn’t belong here. We can throw this out. And so, we ended up actually working quite a bit on our stuff as well. So, it was reviewing what they had and then actually sharing with them what we had as well.

It wasn’t exactly how I planned on spending my spring, but going through the entire course…with fresh eyes I could see some overlaps. I could see some holes. I could see jumps in their <Lecturers> logic where they launch from step A to step B…all the way to G and it’s like, okay how did you get here? And a second-year student is simply not going to understand that gap.

You know, to play even a small role in that <NUSOM Project>, it sort of makes me feel good about myself. That’s why most people volunteer…it makes them feel good about themselves. But, you know, it’s <also> really sort of helping others.

They <the NUSOM faculty> wanted to do the best job that they could, and I felt that it was one of the best mentoring experiences I’ve ever had. They were just really good people to work with.

I think I actually bugged the NUSOM Project leaders saying that I wanted to be part of it. I love teaching in all sorts of different venues because I think that teaching in different venues makes me a better teacher.

So, I’ve taught in all the way from undergraduate, all the way to post-medical, CME conferences. I’ve taught in Japan and those experiences have always been selfishly very beneficial to my knowledge base but also give me an opportunity to teach.

There were some issues about how much we share with this people and copyrighted material and stuff. And I think that had caused so many headaches that by the time it got down to me. People were exhausted by it, and I just gave them everything.

I think the problem boils down to it’s one thing to sit here and plan how best to work with them, and it’s another to get there and realize what they need is different from what you planned on doing with them.

I actually was asked if I wanted to go. I am the current <prominent leadership role> here, and I have kids and a <physician> husband. So for me to disappear for 10 days would be nothing short of catastrophic right now. So, like I have clinical duties and parenting duties left and right that would have amounted to parsing out and dumping on about 10 different people lots of stuff, and trying to manage it from thousands of miles. So, no I decided that was not going to work for me.

Since I didn’t travel, participating didn’t impact my work here at all, except for the occasional early mornings, but it wasn’t bad. But no more so than I would normally experience.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Busse, H.; Azazh, A.; Teklu, S.; Tupesis, J.P.; Woldetsadik, A.; Wubben, R.J.; Tefera, G. Creating change through collaboration: A twinning partnership to strengthen emergency medicine at Addis Ababa University/Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital--A model for international medical education partnerships. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2013, 20, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, O.A.; Pietroni, M.; Cravioto, A. Global health education: International collaboration at ICDDR,B. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2010, 28, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolars, J.C.; Cahill, K.; Donkor, P.; Kaaya, E.; Lawson, A.; Serwadda, D.; Sewankambo, N.K. Perspective: Partnering for medical education in Sub-Saharan Africa: Seeking the evidence for effective collaborations. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorntz, B.; Boissevain, J.R.; Dillingham, R.; Kelly, J.; Ballard, A.; Scheld, W.M.; Guerrant, R.L. A trans-university center for global health. Acad. Med. 2008, 83, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pallangyo, K.; Debas, H.T.; Lyamuya, E.; Loeser, H.; A Mkony, C.; O’Sullivan, P.S.; E Kaaya, E.; Macfarlane, S.B. Partnering on education for health: Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences and the University of California San Francisco. J. Public Health Policy 2012, 33 (Suppl. S1), S13–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christner, J.G.; Dallaghan, G.B.; Briscoe, G.; Casey, P.; Fincher, R.M.E.; Manfred, L.M.; Margo, K.I.; Muscarella, P.; Richardson, J.E.; Safdieh, J.; et al. The Community Preceptor Crisis: Recruiting and Retaining Community-Based Faculty to Teach Medical Students-A Shared Perspective from the Alliance for Clinical Education. Teach. Learn. Med. 2016, 28, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Graziano, S.C.; McKenzie, M.L.; Abbott, J.F.; Buery-Joyner, S.D.; Craig, L.B.; Dalrymple, J.L.; Forstein, D.A.; Hampton, B.S.; Page-Ramsey, S.M.; Pradhan, A.; et al. Barriers and Strategies to Engaging Our Community-Based Preceptors. Teach. Learn. Med. 2018, 30, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kolars, J.C.; Fang, W.; Zheng, K.; Huang, A.Y.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Y.; Woolliscroft, J.O.; Ke, Y. Collaboration Platforms in China for Translational and Clinical Research: The Partnership Between Peking University Health Science Center and the University of Michigan Medical School. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillmanns, R.W.; Ringwelski, A.; Kretschmann, J.; Spangler, L.D.; Curry, R.H. The profession of medicine: A joint US-German collaborative project in medical education. Med. Teach. 2007, 29, e269–e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Pozo, P.R.; Fins, J.J. The globalization of education in medical ethics and humanities: Evolving pedagogy at Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar. Acad. Med. 2005, 80, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R.S.; Casey, P.J.; Kamei, R.K.; Buckley, E.G.; Soo, K.C.; Merson, M.H.; Krishnan, R.K.; Dzau, V.J. A global partnership in medical education between Duke University and the National University of Singapore. Acad. Med. 2008, 83, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daniel, M.M.; Ross, P.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; de Grave, W. Teacher Perspectives of Interdisciplinary Coteaching Relationships in a Clinical Skills Course: A Relational Coordination Theory Analysis. Teach. Learn. Med. 2018, 30, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, E.D.; Treharne, G.J.; Kitas, G.D. Qualitative methodologies I: Asking research questions with reflexive insight. Musculoskelet. Care 2007, 5, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, E.D.; Treharne, G.J.; Kitas, G.D. Qualitative methodologies II: A brief guide to applying interpretative phenomenological analysis in musculoskeletal care. Musculoskelet. Care 2008, 6, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ramani, S.; Mann, K. Introducing medical educators to qualitative study design: Twelve tips from inception to completion. Med. Teach. 2016, 38, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starks, H.; Trinidad, S.B. Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kanter, S.L. International Collaborations Between Medical Schools: What Are the Benefits and Risks? Acad. Med. 2010, 85, 1547–1548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waterval, D.G.; Frambach, J.M.; Oudkerk Pool, A.; Driessen, E.W.; Scherpbier, A.J. An exploration of crossborder medical curriculum partnerships: Balancing curriculum equivalence and local adaptation. Med. Teach. 2016, 38, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waterval, D.G.J.; Driessen, E.W.; Scherpbier, A.; Frambach, J.M. Twelve tips for crossborder curriculum partnerships in medical education. Med. Teach. 2018, 40, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dybowski, C.; Harendza, S. Validation of the Physician Teaching Motivation Questionnaire (PTMQ). BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kohli, A.; Schuh, R.; McDonald, M.; Arita, A.; Elnicki, D.M. Faculty Reflections About Participating in International Medical School Curriculum Development, a Qualitative Study. Int. Med. Educ. 2025, 4, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020007

Kohli A, Schuh R, McDonald M, Arita A, Elnicki DM. Faculty Reflections About Participating in International Medical School Curriculum Development, a Qualitative Study. International Medical Education. 2025; 4(2):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020007

Chicago/Turabian StyleKohli, Amar, Russell Schuh, Margaret McDonald, Ana Arita, and David Michael Elnicki. 2025. "Faculty Reflections About Participating in International Medical School Curriculum Development, a Qualitative Study" International Medical Education 4, no. 2: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020007

APA StyleKohli, A., Schuh, R., McDonald, M., Arita, A., & Elnicki, D. M. (2025). Faculty Reflections About Participating in International Medical School Curriculum Development, a Qualitative Study. International Medical Education, 4(2), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020007