Structured Reporting in Radiology Residency: A Standardized Approach to Assessing Interpretation Skills and Competence

Abstract

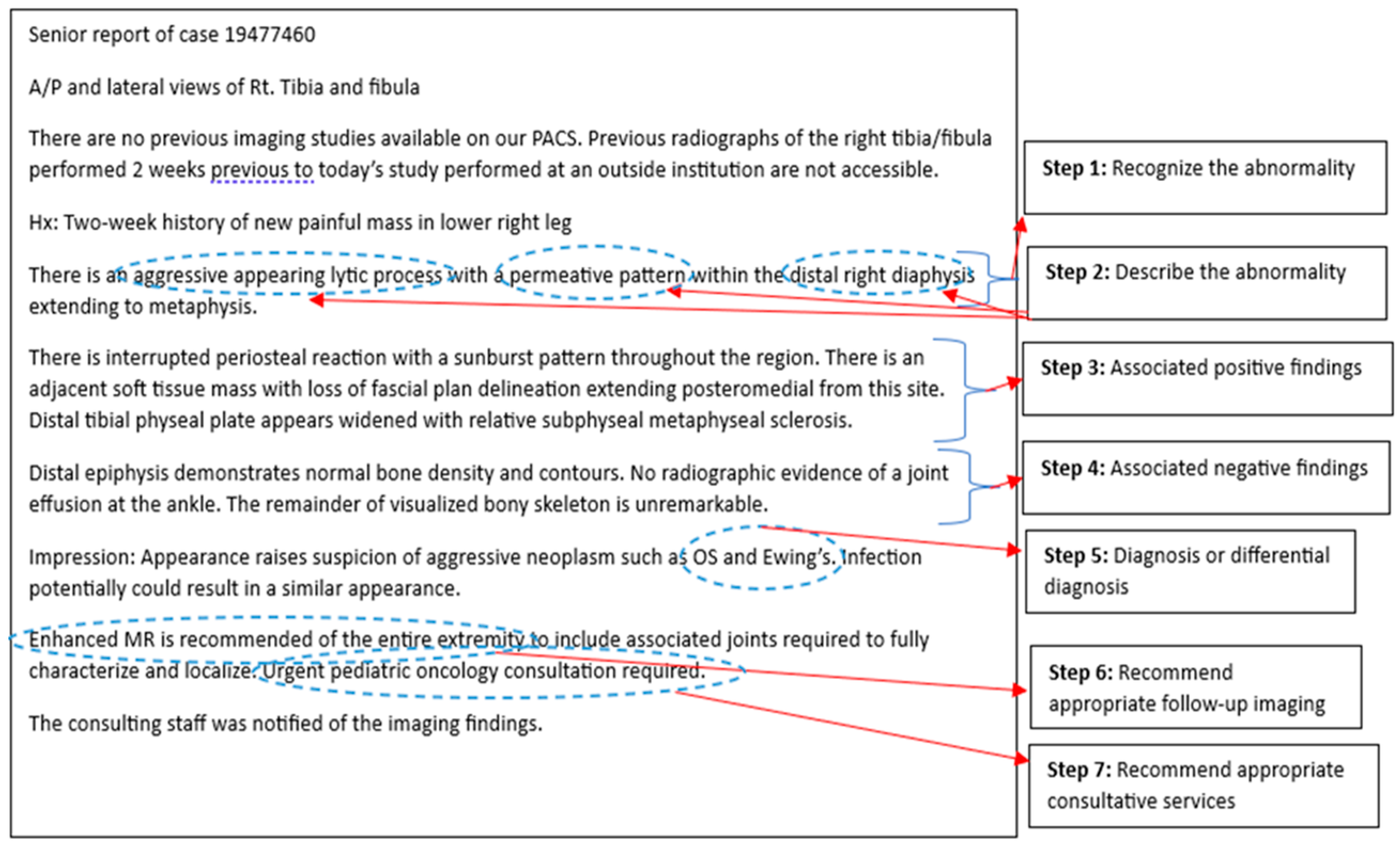

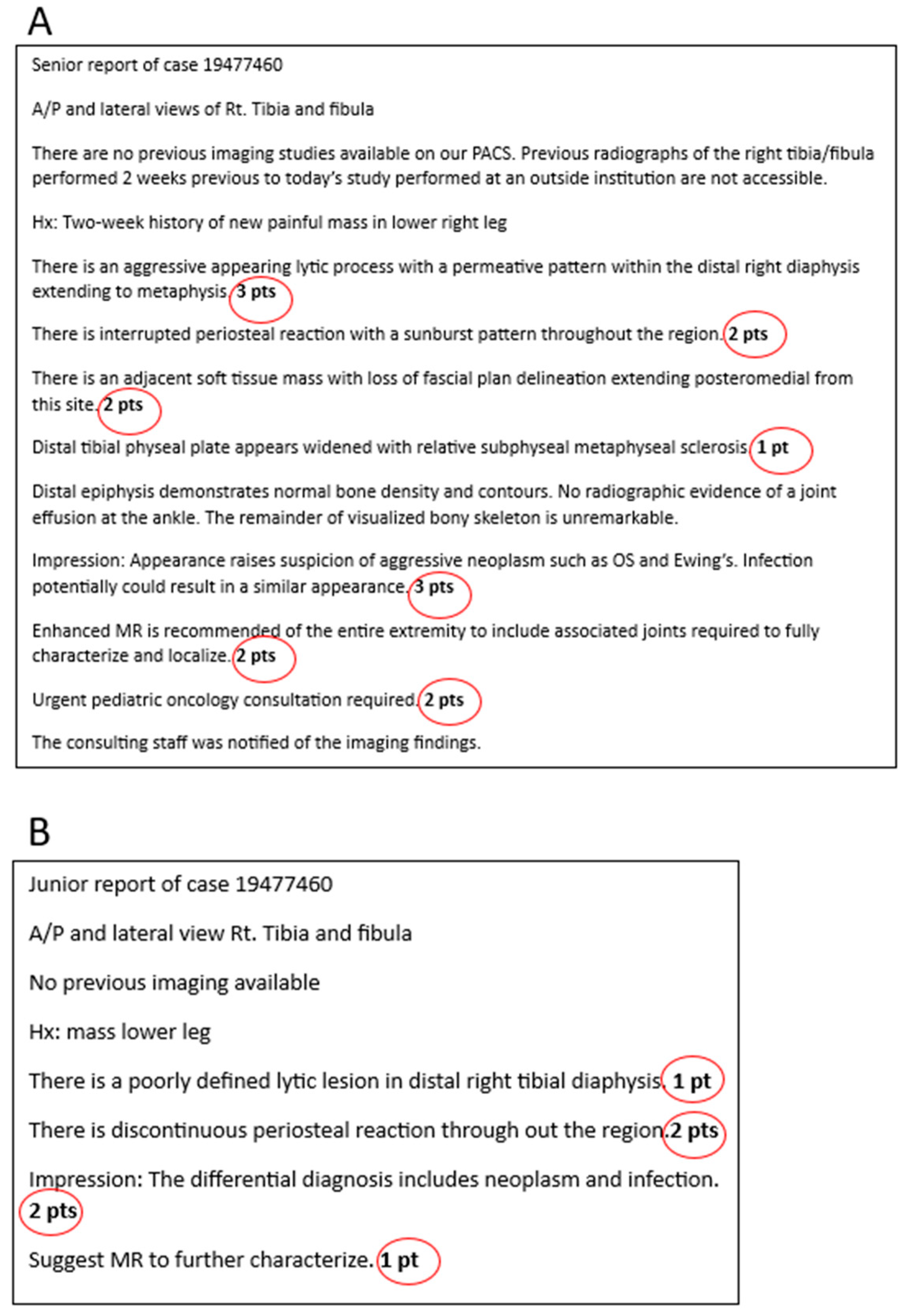

- Similar to the first year intern recognizing who is sick and requires urgent treatment versus who may be sick but there is time to investigate, the radiology resident must learn to recognize which images are normal or abnormal early on in training. This forms the foundation for ‘on-call’ responsibility and is reliant on knowledge gained from medical school, early resident teaching/boot-camp experience and, to some degree, the resident’s inherent perceptual skills.

- After acquiring that initial ability to recognize that there is an imaging abnormality, the resident begins to progressively learn how to describe the finding, using the expected nomenclature. This knowledge is gained through exposure with the attending radiologist during block rotations that continue through residency and through available learning resources.

- As the resident acquires further imaging knowledge and experience, the thought and reasoning processes are focused on advancing their perceptual and descriptive skills to include significant associated ‘positive’ imaging findings, supporting the diagnosis they now have in their mental knowledge bank and are considering in that particular case.

- With ongoing exposure to varying disease processes, associated imaging and an advancing imaging knowledge base, the progressing resident learns to recognize the value of significant ‘negative’ findings on the imaging study, which can help lead to a more useful consultative report and accurate diagnosis, in order to better guide patient management.

- As the resident progresses through residency and this initial learning pathway of recognizing, describing, and evaluating for significant positive and negative findings, they will become increasingly more confident with their suspected diagnosis and potential differential diagnoses, when appropriate.

- Continuing on their learning path, the resident gains more familiarity and experience with the different available imaging modalities, becoming knowledgeable about their advantages/disadvantages through further exposure during block rotations, and becoming competent in recommending appropriate further necessary imaging, as is needed, to guide patient management.

- Finally, nearing the end of training, the resident will have had exposure to and teaching on most imaging diagnoses and the available imaging modalities. Combined with their specialty rounds/consultations and growing responsibility in patient management during training, the resident will have gained the experience to recommend appropriate consultation to a subspecialty service, together with the knowledge of what needs to come next for the patient and with what urgency.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rockall, A.G.; Justich, C.; Helbich, T.; Vilgrain, V. Patient communication in radiology: Moving up the agenda. Eur. J. Radiol. 2022, 155, 110464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, B.Y.M.; Mussari, B.; Moore, P.; Meilleur, L.; Islam, O.; Menard, A.; Soboleski, D.; Cofie, N. A pilot study on diagnostic radiology residency case volumes from a Canadian perspective: A marker of resident knowledge. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2020, 71, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildenberg, J.C.; Chen, P.-H.; Scanlon, M.H.; Cook, T.S. Attending radiologist variability and its effect on radiology resident discrepancy rates. Acad. Radiol. 2017, 24, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyalingam, T.; Walsh, C.M.; Tavares, W.; Mylopoulos, M.; Hodwitz, K.; Liu, L.W.; Heitman, S.J.; Brydges, R. Variable or fixed? Exploring entrustment decision making in workplace-and simulation-based assessments. Acad. Med. 2022, 97, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Catanzano, T.M.; Schaefer, P.W.; Agarwal, V.; Kim, D.; Goiffon, R.J.; Jordan, S.G. Structured reports and radiology residents: Friends or foes? Acad. Radiol. 2022, 29, S43–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutgers, D.R.; Van Raamt, F.; Ten Cate, T.J. Development of competence in volumetric image interpretation in radiology residents. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Entrustable Professional Activities for Diagnostic Radiology. Available online: https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/documents/ibd/diagnostic-radiology-str-e.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Yudkowsky, R.; Park, Y.S.; Lineberry, M.; Knox, A.; Ritter, E.M. Setting mastery learning standards. Acad. Med. 2015, 90, 1495–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, D.; Yang, J.; Greer, M.L.; Kwan, B.; Sauerbrei, E.; Hopman, W.; Soboleski, D. Competency-based medical education—Towards the development of a standardized pediatric radiology testing module. Acad. Radiol. 2020, 27, 1622–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusic, M.; Pecaric, M.; Boutis, K. How much practice is enough? Using learning curves to assess the deliberate practice of radiograph interpretation. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hejri, S.M.; Jalili, M. Standard setting in medical education: Fundamental concepts and emerging challenges. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2014, 28, 34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro, D.; Mishra, S.; Kwan, B.Y.M.; Nasir, M.U.; Daneman, A.; Soboleski, D. Structured Reporting in Radiology Residency: A Standardized Approach to Assessing Interpretation Skills and Competence. Int. Med. Educ. 2025, 4, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4010002

Castro D, Mishra S, Kwan BYM, Nasir MU, Daneman A, Soboleski D. Structured Reporting in Radiology Residency: A Standardized Approach to Assessing Interpretation Skills and Competence. International Medical Education. 2025; 4(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro, Denise, Siddharth Mishra, Benjamin Y. M. Kwan, Muhammad Umer Nasir, Alan Daneman, and Donald Soboleski. 2025. "Structured Reporting in Radiology Residency: A Standardized Approach to Assessing Interpretation Skills and Competence" International Medical Education 4, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4010002

APA StyleCastro, D., Mishra, S., Kwan, B. Y. M., Nasir, M. U., Daneman, A., & Soboleski, D. (2025). Structured Reporting in Radiology Residency: A Standardized Approach to Assessing Interpretation Skills and Competence. International Medical Education, 4(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4010002