Design and Assessment of a Multidisciplinary Training Programme on Child Abuse and Child Protection for Medical Students Comprising Coursework and a Seminar

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Sample Size and Sampling

2.4. Study Population

2.5. Data Collection Instruments and Methods

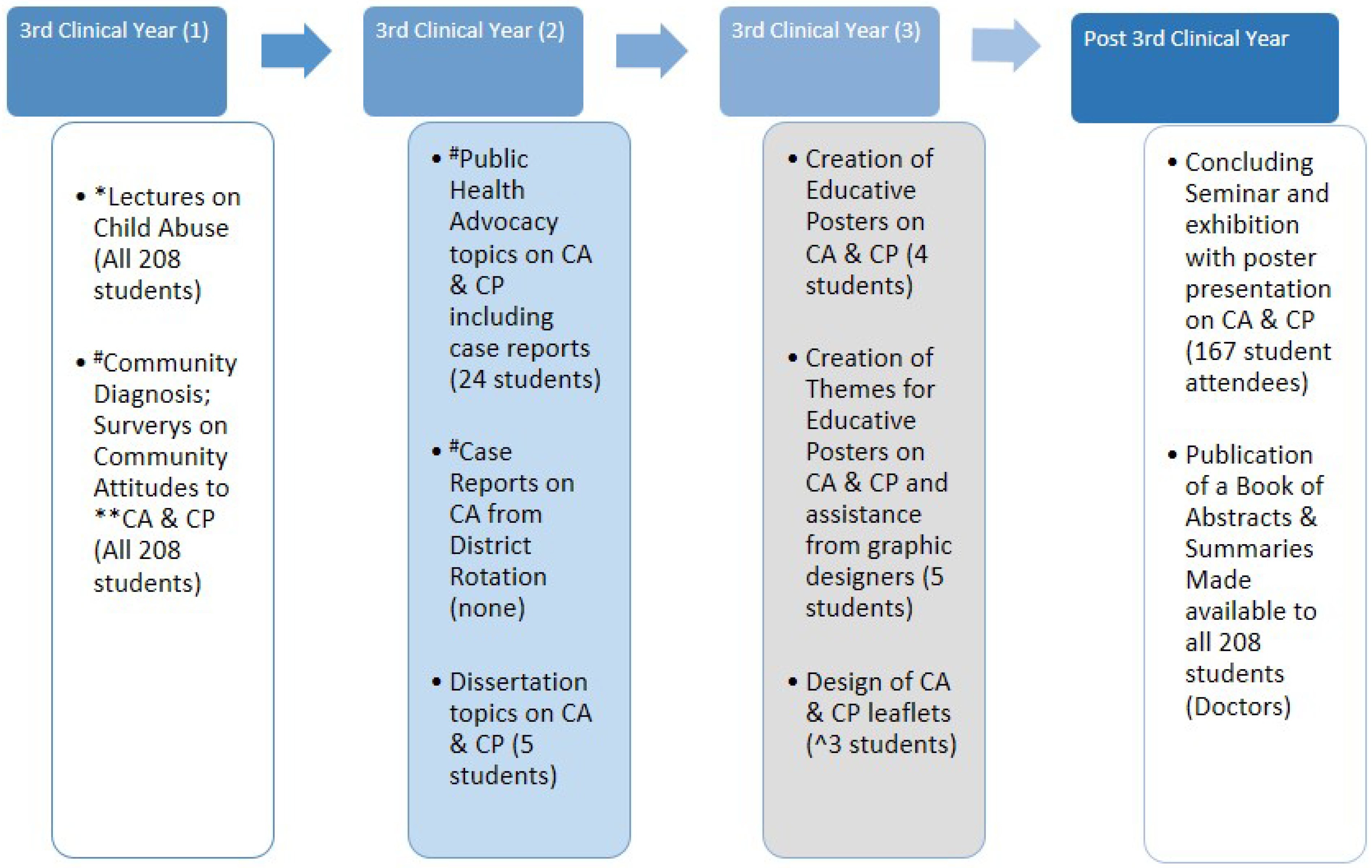

2.5.1. The Intervention—Child Abuse Child Protection Training Programme Coursework in Community Health

Aim and Objectives of the Training Programme

Selection of Topics and Posters for the Seminar

Tutoring and Outputs

Structure of the Concluding Seminar

2.6. Student Assessment

2.7. Data Handling and Analysis

2.8. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. The Concluding Seminar

3.2. Awards and Outputs

3.3. The Student Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wireko, V. ADISCO Bullying Saga. Graphic NewsPLUS App Opinion. 29 July 2023. Available online: https://www.graphic.com.gh/features/opinion/adisco-bullying-saga.html (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Antiri, K.O. Types of Bullying in the Senior High Schools in Ghana. J. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Web. Social Media Users Call for the Arrest of Shatta Bandle over Child Abuse. 25 December 2022. Available online: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/entertainment/Social-media-users-call-for-the-arrest-of-Shatta-Bandle-over-child-abuse-1685864 (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- Crime and Punishment. Kasoa Ritual Murder: Investigator Details How 2 Boys Buried 10-Year-Old Alive in 2021. Available online: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Kasoa-ritual-murder-Investigator-details-how-2-boys-buried-10-year-old-alive-in-2021-1868186 (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- BBC. Ghana’s Baby–Harvesting Syndicate Arrested, Africa 21 January 2021. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55751290 (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Child Protection Companion; RCPCH: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Working Together to Safeguard Children: A Guide to Inter-Agency Working to Safeguard and Promote the Welfare of Children, DFE-000195-2018, HM Government, 2018, CROWN 2920. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/working-together-to-safeguard-children--2 (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- UNICEF/MOH/GHS. Child Protection Guidelines for Health Workers 2018, 1st ed.; UNICEF Ghana and Ghana Health Service: Accra, Ghana, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, N.; Sadler, D. Non-accidental injury for medical students—Is case-based e-learning effective? [version 1]. MedEdPublish 2020, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Child Maltreatment, June 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Pollett, J.; Gurr, S. Child Abuse Investment: Investing in Children Earns Huge Dividends. Report on Investment, Budgeting, and Economic Burden of Child Protection Violations in Ghana, July 2015. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/ghana/media/1941/file/Investing%20in%20children.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Pelletier, H.L.; Knox, M. Incorporating Child Maltreatment Training into Medical School Curricula. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2017, 10, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannon, M.J.; Carter, Y.H. Paediatricians and child protection: The need for effective education and training. Arch. Dis. Child. 2003, 88, 560–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lupariello, F.; Capello, F.; Grossi, V.; Bonci, C.; Di Vella, G. Child abuse and neglect: Are future medical doctors prepared? Legal Med. 2022, 58, 102100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protecting Children and Young People, 2012; Updated May 2018. Available online: www.gmc-uk.org/guidance (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Bahmed, F.; David, M.A.; Arifuddin, M.S. Impact of Seminars By and For Medical Students. Natl. J. Integr. Res. Med. 2014, 5, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- University of Ghana Medical School. History of Medical School. Available online: https://smd.ug.edu.gh/about/history-medical-school (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Bloom, B.S. Learning for mastery. Instruction and curriculum. Regional Education Laboratory for the Carolinas and Virginia, topical papers and reprints, number 1. Eval Comment 1968, 1, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Shabde, N. Child protection training for paediatricians. Arch. Dis. Child. 2006, 91, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Safeguarding Children and Young People: Roles and Competencies for Paediatricians. Available online: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-08/safeguarding_cyp_-_roles_and_competencies_for_paediatricians_-_august_2019_0.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Basheer, B.; Alzomaili, A.; Aldaam, A.; Abalhassan, G.; Almuziri, H.; Alatyan, M.; AlJofan, M.; Al-Kaoud, R. Knowledge and attitudes toward child abuse and neglect among medical and dental undergraduate students and interns in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Imam J. Appl. Sci. 2020, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starling, S.P.; Heisler, K.W.; Paulson, J.F.; Youmans, E. Child Abuse Training and Knowledge: A National Survey of Emergency Medicine, Family Medicine, and Pediatric Residents and Program Directors. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e595–e602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, C.; Manta, A.; Livanou, M.E.; Daniil, V.; Paraskeva, A.; Georgiadou, M.K.; Griva, N.; Papaevangelou, V.; Tsolia, M.; Leventhal, J.M.; et al. Creation and evaluation of a participatory child abuse and neglect workshop for medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.L.; Chen, D.X.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.Y. Effects of seminar teaching method versus lecture-based learning in medical education: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwmeester, R.A.; de Kleijn, R.A.; van Rijen, H.V. Peer-instructed seminar attendance is associated with improved preparation, deeper learning and higher exam scores: A survey study. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Westmoreland, K.D.; Banda, F.M.; Steenhoff, A.P.; Lowenthal, E.D.; Isaksson, E.; Fassl, B.A. A standardized low-cost peer role-playing training intervention improves medical student competency in communicating bad news to patients in Botswana. Palliat. Support. Care 2019, 17, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesgin, M.T.; Tok, H.H. The impact of drama education and in-class education on nursing students’ attitudes toward violence against women: A randomized controlled study. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 125, 105779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadzadeh, A.; Shahrokhi, H.; Shalchi, B.; Khamnian, Z.; Rezaei-Hachesu, P. Digital games and virtual reality applications in child abuse: A scoping review and conceptual framework. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McLean, S.F. Case-Based Learning and its Application in Medical and Health-Care Fields: A Review of Worldwide Literature. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2016, 3, JMECD.S20377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krugman, R.D.; Polland, L.E. How Should We Start the “Do-Over” Is Training the First Step? Int. J. Child Maltreatment 2020, 3, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, K.E. Culture and Nondisclosure of Child Sexual Abuse in Ghana: A Theoretical and Empirical Exploration. Law Soc. Inq. 2009, 34, 951–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Jordan, L.P.; Emery, C.R. The protective effects of the collective cultural value of abiriwatia against child neglect; Results from a nationally representative survey. Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 138, 106068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tette, E.M.A. UGMS Class of 2022, Department of Community Health. Child Abuse and Child Protection Awareness and Practice in the La Nkwantanang Madina Municipal: Implications for child protection policy and services. UGMS Res. Newsl. 2024, 24, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Seminar Topics |

|---|---|

| 1 | The definition, types and public health significance of child abuse |

| 2 | * The epidemiology of child abuse |

| 3 | The health and psycho-social effects of child abuse |

| 4 | Culture and child abuse |

| 5 | Domestic violence and child abuse |

| 6 | * Developmental conditions and child abuse |

| 7 | Diagnosing physical abuse |

| 8 | Diagnosing sexual abuse |

| 9 | Diagnosing neglect |

| 10 | A case report on physical abuse |

| 11 | A case report on sexual abuse |

| 12 | A case report on neglect |

| 13 | Guidelines and procedures for managing child abuse in the hospital |

| 14 | Guidelines and procedures for managing child abuse in the community and the role of social welfare services |

| 15 | Forensic medicine, infectious diseases and sexual abuse |

| 16 | Multidisciplinary working and agencies involved in child protection |

| 17 | The Domestic Violence and Victims Support Unit (DOVVSU) |

| 18 | Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ) |

| 19 | Prevention of child abuse |

| Dissertations | |

|---|---|

| 1 | * A Study of the Knowledge and Response to Child Abuse Among Healthcare Workers in Ghana |

| 2 | Child Abuse and Health Challenges Facing Street Children in Accra |

| 3 | Perceptions of child abuse among Junior High School pupils of St Mary’s Roman Catholic Girls Basic School |

| 4 | # Knowledge Attitudes and Practices of Adolescent School Girls Attending St Mary’s Senior High School Regarding Child Abuse and Child Protection |

| 5 | Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Child Abuse and Adoptive Measures among students at Ebenezer Senior High School, Accra |

| Community Surveys | |

| 1 | Knowledge, prevalence and positive parenting skills relating to Child Abuse Among residents of New Adoteiman |

| 2 | Child Abuse in Oyarifa: A Survey of the Knowledge, Prevalence and Positive Parenting Skills |

| 3 | * An Assessment of the Knowledge, Attitudes And Practices (KAP) Towards Child Abuse in The Peri-urban Town of Old-Adoteiman |

| 4 | Assessing the Knowledge, Prevalence and Positive Parenting Skills Among The People of Danfa South Concerning Child Abuse |

| 5 | Child Abuse in Danfa North: A Survey of The Knowledge, Prevalence and Positive Parenting Skills. |

| 6 | Knowledge of Child Abuse, Prevalence and Positive Parenting Skills in Otinibi, Greater Accra Region |

| 7 | Child Abuse in Kweiman: A survey of the knowledge prevalence and positive parenting skills |

| Posters and leaflets | |

| 1 | * 4 posters (fully self-designed by students) |

| 2 | 5 posters (words provided by students) |

| 3 | * 3 leaflets |

| Outputs | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Concluding Seminar |

| 2. | Exhibition |

| 3. | Awards |

| 4. | Book of Abstracts and Summaries (This was given to majority of the students when they became house officers) |

| 5. | Policy brief for the Minister of Gender, Children and Social Protection |

| 6. | Posters and a leaflet used during celebration of the child health week in a public hospital in 2023 |

| 7. | Continuous Professional Development (CPD) points given to doctors who attended the event |

| 8. | A video and teaching-aid for teaching child abuse/child protection |

| * Questions and Statements | Frequency of Correct Answers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition of Child Abuse | ||

| ||

| Child abuse occurs when there is harm done to a child as a result of acts of commission or omission | 111 | 88.8 |

| The action may be intentional, reckless, and inflicted by the family, community or institution or another child | 116 | 92.8 |

| Harm is ill-treatment or the impairment of health or development | 87 | 69.6 |

| Boys are often the victims of beatings | 86 | 68.8 |

| Girls are prone to sexual abuse, forced prostitution | 114 | 91.2 |

| Girls are often victims of education and nutrition neglect | 78 | 62.4 |

| Respondents: 125 out of 126 respondents answered this question. | ||

| ||

| Inflicting pain on a child is a form of child abuse | 120 | 96.0 |

| Inflicting hunger on a child is a form of child abuse | 116 | 92.8 |

| Depriving a child of education is a form of child abuse | 114 | 91.2 |

| Overworking a child is a form of child abuse | 114 | 91.2 |

| Overprotecting a child | 9 | 7.2 |

| Respondents: 125 out of 126 respondents answered this question. | ||

| ||

| Repetitive injuries | 118 | 95.2 |

| Injuries not consistent with the story | 116 | 93.6 |

| Vague or inconsistent story | 108 | 87.1 |

| Previous evidence of abuse | 105 | 84.7 |

| Unique pattern of injuries | 100 | 80.7 |

| Delay in seeking medical help | 100 | 80.7 |

| A child with sexualized behaviour | 87 | 70.2 |

| Allowing a child to overeat and become obese | 18 | 14.5 |

| Respondents: 124 out of 126 respondents answered this question | ||

| Recognition of Different Forms of Child Abuse | ||

| ||

| Physical abuse | 121 | 98.4 |

| Sexual abuse | 119 | 96.8 |

| Emotional abuse | 117 | 95.1 |

| Neglect | 112 | 91.1 |

| Exploitation | 92 | 74.8 |

| Respondents: 123 out of 126 respondents answered this question | ||

| ||

| Shaking | 92 | 73.6 |

| Throwing | 111 | 88.8 |

| Rape or oral sex involving a child | 32 | 25.6 |

| Burning | 116 | 92.8 |

| Choking | 115 | 92.0 |

| Making an under-age person or child pregnant | 25 | 20.0 |

| Asking a child to do hard work | 67 | 53.6 |

| Carrying heavy loads | 81 | 64.8 |

| Respondents: 125 out of 126 respondents answered this question | ||

| Epidemiology of Child Abuse | ||

| ||

| Child abuse can have a multigenerational impact | 96 | 85.0 |

| Nearly 3 in 4 or 300 million children aged 2–4 years regularly suffer physical punishment and/or psychological violence at the hands of parents and caregivers | 76 | 67.3 |

| One in 5 women and 1 in 13 men report having been sexually abused as a child 0–17 years | 51 | 45.1 |

| 120 million girls and young women under 20 years of age have suffered some form of forced sexual contact | 36 | 31.9 |

| Child abuse costs Ghana GHC 926 million to GHC 1.442 billion/year | 22 | 19.5 |

| Respondents: 113 out of 126 respondents answered this question | ||

| Risk Factors And Preventive Measures | ||

| ||

| Poverty | 124 | 99.2 |

| Alcoholism | 123 | 98.4 |

| Drug abuse | 120 | 96.0 |

| A great number of unwanted children | 117 | 93.6 |

| Lack of support | 108 | 86.4 |

| Promiscuity | 88 | 70.4 |

| Respondents: 125 out of 126 respondents answered this question | ||

| ||

| Creating awareness and dialogue with chiefs, religious leaders, and prayer camp leaders to modify customs and practices within their communities and churches | 116 | 95.1 |

| Increasing girl child enrolment and retention in school | 115 | 94.3 |

| Reducing risk factors such as alcohol and drug abuse in the society | 113 | 92.6 |

| Child welfare clinic interventions and home visiting | 111 | 91.0 |

| Negative parenting | 12 | 9.8 |

| Respondents: 122 out of 126 respondents answered this question | ||

| Students’ Opinion of the Programme | ||

| Aspects of child abuse that have become clearer to you through the programme: | ||

| Where to report abuse | 100 | 82.0 |

| Agencies that protect children and what they do | 100 | 82.0 |

| Risk factors for child abuse | 95 | 77.9 |

| Types of child abuse | 94 | 77.1 |

| Child protection procedures | 85 | 69.7 |

| Properly reporting all the information about the child | 61 | 50.0 |

| Alternative ways to discipline children | 53 | 43.4 |

| None | 1 | 0.8 |

| Respondents: 122 out of 126 respondents answered this question | ||

| Level of Knowledge | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Good (80–100) | Moderate (60–79.0) | Poor (≤59.0) |

| n, (%) | n, (%) | n, (%) | |

| Recognition of Child Abuse | |||

| Knowledge of recognizing child abuse (Q2) | 85 (68.0) | 18 (14.4) | 22 (17.6) |

| Knowledge of suggested presentations of child abuse I (Q3) | 103 (82.4) | 12 (9.6) | 10 (8.0) |

| Knowledge of suggested presentations of child abuse II (Q6) | 66 (53.2) | 41 (33.1) | 17 (13.7) |

| Recognition of Different Forms of Child Abuse | |||

| Knowledge of recognized types of child abuse (Q4) | 112 (91.0) | 5 (4.2) | 6 (4.9) |

| Knowledge of the different categories of child physical abuse (Q5) | 35 (28.0) | 62(49.6) | 28 (22.4) |

| Epidemiology of Child Abuse | |||

| Knowledge on the epidemiology of child abuse (Q1) | 23 (20.4) | 25 (22.1) | 65 (57.5) |

| Risk Factors and Preventive Measures of Child Abuse | |||

| Knowledge of risk factors for child abuse that apply to caregivers (Q7) | 109 (87.2) | 11 (8.8) | 5 (4.0) |

| Knowledge of measures to prevent child abuse (Q8) | 99 (81.1) | 15 (12.3) | 8 (6.6) |

| Comments and Suggestions of Ways the Programme Can Be Modified to Improve It | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 3.9 |

Including other stakeholders

| 7 | 5.5 |

| 6 | 4.7 |

| 3 | 2.4 |

| 3 | 2.4 |

| 3 | 2.4 |

| 2 | 1.6 |

| 2 | 1.6 |

| 2 | 1.6 |

| 1 | 0.8 |

| 1 | 0.8 |

| 1 | 0.8 |

| 1 | 0.8 |

| 1 | 0.8 |

| 1 | 0.8 |

| 1 | 0.8 |

| 1 | 0.8 |

| * Total | 41 | 32.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tette, E.M.A.; Badoe, E.V.; Baddoo, N.A.; Lawson, H.J.O.; Pie, S.; Nartey, E.T.; Lartey, M.Y. Design and Assessment of a Multidisciplinary Training Programme on Child Abuse and Child Protection for Medical Students Comprising Coursework and a Seminar. Int. Med. Educ. 2024, 3, 239-256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime3030020

Tette EMA, Badoe EV, Baddoo NA, Lawson HJO, Pie S, Nartey ET, Lartey MY. Design and Assessment of a Multidisciplinary Training Programme on Child Abuse and Child Protection for Medical Students Comprising Coursework and a Seminar. International Medical Education. 2024; 3(3):239-256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime3030020

Chicago/Turabian StyleTette, Edem Magdalene Afua, Ebenezer V. Badoe, Nyonuku A. Baddoo, Henry J. O. Lawson, Samuel Pie, Edmund T. Nartey, and Margaret Y. Lartey. 2024. "Design and Assessment of a Multidisciplinary Training Programme on Child Abuse and Child Protection for Medical Students Comprising Coursework and a Seminar" International Medical Education 3, no. 3: 239-256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime3030020

APA StyleTette, E. M. A., Badoe, E. V., Baddoo, N. A., Lawson, H. J. O., Pie, S., Nartey, E. T., & Lartey, M. Y. (2024). Design and Assessment of a Multidisciplinary Training Programme on Child Abuse and Child Protection for Medical Students Comprising Coursework and a Seminar. International Medical Education, 3(3), 239-256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime3030020