Abstract

Purpose: This study aimed to develop a concept for a mobile health application, an app-based exercise tool, to support the treatment of orofacial myofunctional disorders by speech-language therapists. Method: A sequential mixed research design combining qualitative research and user-centered software development was applied. Qualitative interviews and focus groups were conducted with eight speech-language therapists, one patient and three relatives to gather ideas for an app to support orofacial myofunctional therapy. On the basis of the findings, a paper-based prototype was developed, which was then evaluated by seven end users, to refine the concept of the app. Results: Qualitative data on desirable functionalities were clustered into topics and related subcategories containing general ideas for the app – a control mechanism, a reward system, the visualization of exercises, and pop-up messages for reminders and recommendations. The paper prototype was developed that addressed these functionalities. Discussion: An app-based exercise tool is considered to have added value for orofacial myofunctional therapy. A prototype for a mobile application is ready for programming and subsequent testing in the treatment of orofacial myofunctional disorders by conducting additional interviews to ascertain patients’ perceptions.

INTRODUCTION

Orofacial myofunctional disorders (OMD) are abnormal movement patterns of the face and mouth that may occur in children as well as in adults (Fischer-Voosholz & Spenthof, 2002). The main signs and symptoms are orofacial abnormalities, lip incompetence, open-mouth breathing, abnormal tongue resting posture, inappropriate anterior movement (thrusting) of the tongue while swallowing and chewing, and speech-sound distortions. Accompanying parafunctional oral habits, such as abnormal thumb, finger, lip and tongue sucking habits and bruxism, may also occur (Benkert, 1997; Fischer-Voosholz & Spenthof, 2002; Homem et al., 2014; Mason, 2005). These abnormal movement patterns and habits can result in a disruption of dental development in children and may lead to dental malocclusions (Moss, 2003; Proffit, 1973).

In Germany, the reported prevalence of OMD varies between 60.6% (Grabowski et al., 2007) (3041 German children, average age 4.5 yr) and 19.8% (Meilinger, 1999) (102 German children between the age of 5 and 7 yr). Here, treatment of OMD is a relatively young field (Fischer-Voosholz & Spenthof, 2002), yet it is crucial for gaining sustainable outcomes within orthodontic treatment (Klocke et al., 2000).

Over the years, different kinds of orofacial myofunctional treatment (OMT) concepts have been developed in Germany using a variety of approaches. However, most of these concepts lack evidence of effectiveness. The lack of a general treatment guideline highlights this research gap (Furtenbach & Wallner, 2009; Ruben & Wittich, 2014). Expert interviews conducted by Ruben and Wittlich (2014) showed that most speech-language therapists (SLTs) in Germany use the concept of Kittel (2014), a method to correct inaccurate swallowing patterns by using different exercises to train facial muscles, or their own set of exercises based on various concepts and their experience in practice.

In general, OMT concepts require regular practice by the patients to achieve correct movement patterns and behavioral change. However, when behavioral changes such as the correct tongue rest posture have not been automated, there is a high risk for patients to return to old patterns (Freudenberg et al., 2019). Klocke et al. (2000) found that the lack of cooperation by patients and parents of child-age patients was the main reason for therapy failure. Expert interviews by Ruben and Wittlich (2014) noted that patients and therapists described exercises in OMT as dull and boring. Furthermore, 24% of SLTs fully and 47% of SLTs rather agreed that transferring the learned skills into everyday life was one of the core issues in OMD treatment. Kazantzis et al. (2016) also described the adherence to behavioral change as related to treatment success, but also as susceptible to interference.

EHealth applications may be an adequate support for OMD therapy as they can combine those beneficial factors influencing therapy efficiency. In addition, especially during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of eHealth in SLT in Germany became apparent. With increasing interest in eHealth, the use of electronic reminder systems to promote treatment adherence also increased. Reminder systems, such as short text messages (SMS) or e-mail notifications, which are intended to remind patients of certain types of behavior, showed positive effects on both the adherence to therapy and the therapy’s success in some cases (Marcolino et al., 2018; Mbuagbaw et al., 2015; Yasmin et al., 2016). In general, the use of mobile applications (apps) in SLT shows potential, but only a few specialized apps are available (Furlong et al., 2018; Starke & Mühlhaus, 2018). A search for oral-motor therapy apps in the Google Play Store and on the website TherapiePAD showed that some apps are available, but most are not specific for OMD and have limited functions to provide rewards, feedback and support for patients of all ages. There was also no sign of an evidence-based approach to their development process (Fillbrandt, 2021; Google Play Store, 2021; PubMed, 2021). Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop a concept for an app to support the therapy of OMD in children and adults based on input from SLTs and end users.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

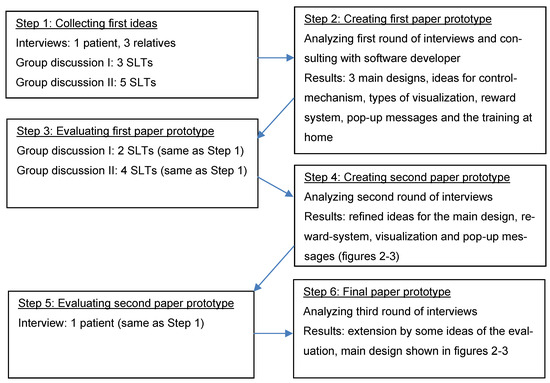

To develop a concept for the app, a sequential mixed research design was chosen. It combines qualitative research and user-centered software development. It also comprises a multi-staged process and includes interviews and focus groups with stakeholders as well as derivation and evaluation of paper-based prototypes. Figure 1 illustrates the overview of the research process. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of Heidelberg (S-362/2019).

Figure 1.

Overview of the research process.

Recruitment and Study Population

Participants were recruited through a convenience sample of SLT practices around Karlsruhe, Mannheim and Heidelberg in Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany. The practices were identified by internet research and personal network of professionals. During the first contact, the practices received general information about the study. After contacting the project coordinator, the interested practices received the study documents to pass along to patients with OMD, relatives and SLTs. Inclusion criteria were: State-approved SLTs and similar professions, patients diagnosed with OMD over the age of 18 years, patients with OMD over the age of 14 years with the permission of the guardian, or relatives of patients with OMD. All participants gave their written informed consent prior to data collection. Recruitment of participants started in June 2019 and ended in August 2019. The interviews, focus groups and data analysis were conducted by the first author, who is a German SLT with 5 years of work experience and additional training in interprofessional healthcare, health services research and implementation science.

Procedure

- Step 1: Collecting initial ideas

First ideas were gathered by interviewing potential end-users. The qualitative data were obtained through focus groups with SLTs and interviews with patients and relatives. These two formats were chosen because of practicability. The focus groups and interviews were documented by audio and video recording or by “amolto call recorder” (Amolto, 2020) in the case of interviews via teleconferencing. All interviews were transcribed following the verbatim transcription guideline of the Department of General Practice and Health Services Research University Hospital Heidelberg (Versorgungsforschung, 2017). The material was initially coded in MAXQDA Standard 2018 (Verbi GmbH, 2018) based on Emerson’s open coding (Emerson et al., 1995). The codes concerning the ideas for the app were then written onto Post-it® sticky notes and clustered into categories. To resolve discrepancies in data coding and to consider main ideas emerging from the interviews, the first author (CO) consulted with the supervisor of the thesis (AW) until consensus was reached.

- Step 2: Creating the first paper prototype

To ensure feasibility, the first author presented the ideas gathered in Step 1 to a software developer who verified these in a discussion. The remaining codes including feasible app-features were then visualized within a first paper prototype following User Experience Prototyping (UX Prototyping) (Richter & Flückiger, 2016). This paper prototype consisted of drawings and bullet point topics arranged by the first author using the codes from Step 1.

- Step 3: Evaluation of the first paper prototype

During this phase, a second round of focus groups of SLTs was conducted. Because of the processual character of this study, the same group of SLTs was recruited. The aim of these sessions was to refine the functions and the design of the future app. After a short presentation of the paper prototype, participants were asked to choose their favorites out of the three main app designs and three reward systems. They were also asked to rank different functions according to their importance and encouraged to share whatever ideas came to mind. Remarks were directly noted by participants and the moderator, and pinned to the corresponding area of the flip chart. In addition to audio and video recordings, the different stages of development were documented by photos. The focus groups were transcribed following the verbatim transcription guideline and were opencoded by hand (Emerson et al., 1995) based on the categories defined during Step 1.

- Step 4: Creating the second paper prototype

Based on the results of Step 3, the paper prototype was modified and expanded following UX Prototyping (Richter & Flückiger, 2016). The codes from Step 1 were refined. Ideas concerning new functions, the design, usability and motivation of the patient were considered. For better visualization, the second paper prototype was designed by means of Autodesk Sketch Book for Microsoft Windows 10 (Autodesk Inc., 2018).

- Step 5: Evaluation of the second prototype

During this phase, one interview was conducted with one patient to evaluate the second paper prototype. Because of the processual character of this study, the same patient as in Step 1 was chosen to evaluate the prototype. The prototype was presented and then discussed. Potential modifications and ideas were directly written down by the moderator. The last step was to adapt the paper prototype to produce the final version.

RESULTS

Participants

On the whole, four focus groups with practices in the Rhein-Neckar-Region took place, two in the first interview round, with three and five SLTs, and two in the second round, with two and four SLTs. One former patient over the age of 18, who attended 20 therapy sessions for OMD treatment, was interviewed in the first round and asked to evaluate the second prototype. The other three interviews were conducted with three relatives of patients under the age of 14 with OMD.

General Ideas

The discussions from this research process revealed several features that should generally be provided by the app and depicted the setting in which it would be used. The most important idea for SLTs, relatives and the patient implied separate versions for therapists and patients, allowing the therapists to act as an administrator. The possibility of including any treatment plan was seen to be essential for the app. Furthermore, a training for SLTs on how to use the app was considered necessary to make sure SLTs can use the app adequately. Participants suggested that a demo version of the app should be provided for SLTs and patients so that they could test it before buying the full version. There were different views on the costs of the app. Some patients were willing to pay up to 20 €, while others wanted it to be free of charge. SLTs suggested high-priced versions for professional practice and free versions for the patients. Participants expected practices to be properly equipped for the use of the app. Participants mentioned that the app should not use too much space on the device in order to make the download easier and more accessible. One patient also suggested a potential connection between the app and the practice software system as well as an interface function between the app and the patients’ smart phone calendar. Thus, cancellations of sessions could be carried out easily.

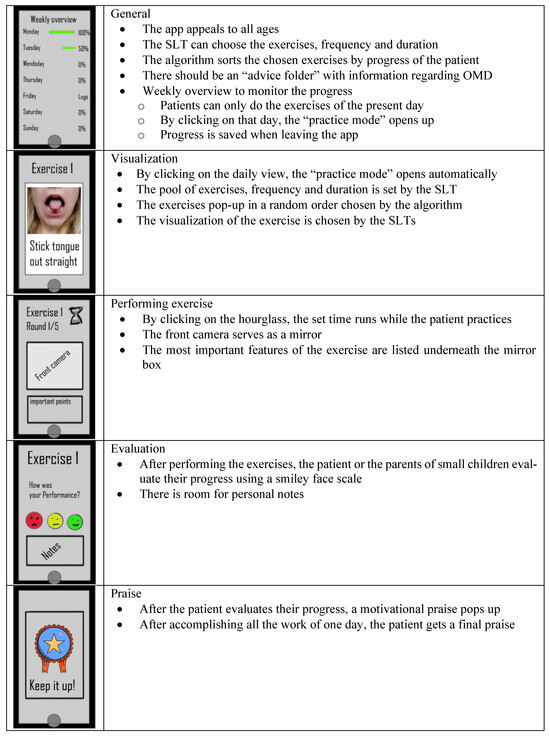

Main Design

Three different main designs for the app were discussed: (1) a digital exercise plan, (2) a flashcard-system, and (3) a gaming app (Figure 2). The main features of the digital exercise plan contained the possibility for SLTs to choose the at-home exercises and determine their frequency and duration. The patients were supposed to document their progress in the app by checking the exercises. The main idea of the flashcard system was that the exercises the SLTs chose for their patients were sorted by an algorithm depending on patients’ progress. The main idea of the gaming-app was that the patients had to pass different challenges to defeat the final boss, a computer-controlled enemy in video games. The exercises in this version were not to be chosen by the SLTs, but by the patient who actually played the game. Both groups liked a combination of the digital exercise plan and the flashcard system best. They also liked the idea of a gaming app, but they had some concerns about the design being less flexible than the others.

Figure 2.

Main features of a mobile app for treatment of orofacial myofunctional disorders.

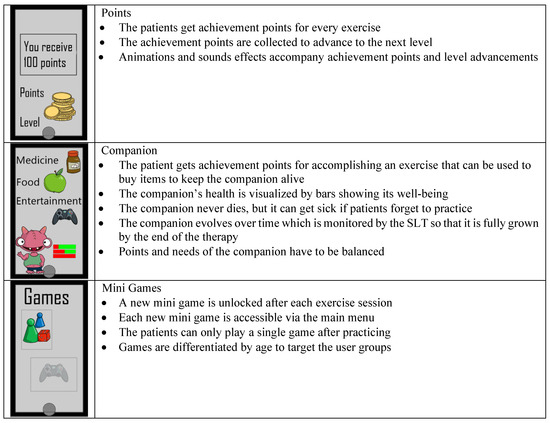

Reward System

Three different types of reward systems were discussed: (1) a concept where patients get a certain number of achievement-points for their performance and level up after some time; (2) a system where patients choose a virtual companion at the beginning and have to keep it alive by doing the exercises; and (3) a reward system where patients can unlock a game every time they practice with the app. Participants proposed a combination of all three reward systems that appealed to all ages. The main features of these three reward systems are listed in Figure 3. The idea of a game world was also popular with the patient and relatives. Exercises were to be placed in a gaming world where patients needed to accomplish different challenges. Financial bonuses for self-payer services and payback points were ideas especially for adult patients. One person had the idea to design exercises as a memory game. Another person thought that two choices of reward systems were enough and that at the end of the therapy process, there should always be a reasonable ending to the app irrespective of the chosen design.

Figure 3.

Reward systems of a mobile app for treatment of orofacial myofunctional disorders.

Pop-up Messages

According to the participants, reminding themselves of doing the exercises is often a problem. Therefore, pop-up messages were demanded to remind patients of doing their homework and of behavioral changes (e.g., resting position of the tongue, swallowing procedure). All of the suggested pop-up messages were to be customizable by the user as to their content, their pop-up times, and their frequency. Two participants thought that a reminder for the next therapy session could be useful as well. Pop-up messages could also be used to give patients assistance through recommendations for their homework. There was no consensus between the groups on whether there should always be pop-up messages to remind patients of their homework, behavioral changes and the next session. One group liked the idea of the app icon changing its color to remind the patients to open the app and see the reminders. The other group approved of direct pop-up messages for reminding patients to practice and to change their behavior but did not like the idea of a reminder for the next session. They were concerned about communication problems between the SLT practice and the patients.

Visualization of the Exercises

To visualize the exercises for the patients, video instruction was the option mentioned most frequently. Photo instruction was rated second. Especially for SLTs, the possibility of customizing the visualization was important. Therefore, the app was expected to use all the features of the device it was downloaded to, such as camera, painting program and messaging to create different visualization types. It was considered necessary that every exercise would have a box with important instructions for the patients to remember during the exercises. The participants expressed that a child-oriented visualization was important so that children could comprehend the exercise and remain motivated, as long as it was not too distracting. The participants discussed the need for a catalogue of existing exercises and the possibility to add new, individually created exercises. Individual exercises could then be saved and shared on a platform for other SLTs and patients to use.

Control Mechanism

There were different types of ideas to evaluate the quality and frequency of performance. The evaluation through the app itself was the option mentioned most frequently. Most of the participants had concerns about this option being too complicated to program, because even the smallest deviations of the tongue need to be registered during the performance. Especially SLTs were concerned that cameras would not capture these small movements and would lead to faulty muscle patterns.

Patients could also film their training and show it to their therapists or contact the therapists via livestream. Other options were self- and external evaluation through written assistance and the front camera used as a mirror. Some SLTs also liked the idea of seeing the frequency with which patients used the app.

DISCUSSION

The focus groups and interviews resulted in a concept for an app to support OMT where the main design is a digital exercise plan. The patient can choose their preferred design, a reward system to maintain patients’ motivation and pop-up messages to remind patients of behavioral change or exercising. The developed paper prototype combined three types of apps: specialized SLT apps, motivational and reward apps, as well as progress-tracking apps (Bilda et al., 2016).

Reward System and Motivation

To customize the reward system to meet patient needs, three different systems were developed. One idea was a point system where the patients get a certain amount of achievement points for each exercise. The second option was playing a game as a reward after an exercise unit. These kinds of rewards are well evaluated in the development of games and can be effective for promoting patients’ motivation (Matallaoui et al., 2017). The use of a companion that patients could care for was the third option discussed. This type of reward system does not only use elements of health gaming and gamification, but also includes elements of para-social relationships. Both elements show potential to promote the patients’ motivation (Przybylski et al., 2010; Ryan et al., 2006; Yee et al., 2007). The idea of complete integration of the exercises in a gameworld was dismissed quite early, since SLTs considered this system to be too rigid. These ideas show that maintaining the motivation of patients was a very important aspect for all participants.

According to the self-determination theory (SDT), autonomy, competence and relatedness are crucial factors for motivation (Ryan et al., 2008). In addition, gamification and health gaming have shown positive effects on patients’ motivation following SDT principals (Matallaoui et al., 2017; Starks, 2014). Most health-related behavior changes are not motivated intrinsically. Representatives of SDT state that in most cases people engage in behavioral change only because of external reward systems, which endangers a sustainable behavioral change (Ryan et al., 2008). Nevertheless, most discussions were about the topic of external motivation, maybe because creating intrinsic motivation in small children and adolescents is challenging. Since many patients with OMD are from these age groups, external motivation should be part of an app for OMT. The developed reward systems are therefore to be seen as a gamification tool to motivate patients to practice at home.

Feedback

Concerning the feedback method provided by the app, there was no initial consensus. Patients and relatives wished to have an app that monitors the facial movement of the patients to evaluate the exercises. This would require an Artificial Intelligence (AI) system that recognizes not only minimal differences between face, lip and jaw position, but also hidden movements of the tongue inside the mouth. SLTs also liked the idea initially but were afraid that this kind of control mechanism would be too imprecise for OMT. There were also some concerns about the implementation of the app with this feature in SLT practices. SLTs might think that this would endanger their professional role in OMT and therefore boycott the use of this app. All the SLTs agreed that the selfor external evaluation of patients and their relatives would be sufficient. One patient expressed concerns that an app using AI might have too much control. For these reasons, this option was excluded from further development of the paper prototype. However, this idea could be reconsidered for further development since automatic recognition of movement patterns could support OMT, especially for patients and relatives with poor sensory perception skills.

Flexibility

The customizability was mentioned by participants as an important feature of the app. By choosing the exercises, duration and frequency, SLTs can adapt the therapy to the patients’ needs. This might be a feasible way to directly tailor interventions to patients’ requirements. The openness of the app to create one’s own exercises gives the SLTs the possibility to choose any treatment plan they find best for their patients. The digital exercise plan combined with a flashcard system was also seen as a positive feature of the app. The exercise plan could act as a mobile checklist to help patients follow the schedule and simultaneously offer the opportunity to document problems performing certain exercises. This would allow patients and relatives to be more flexible as to where they do their training. Gačniket al. (2018) found this independence to be one of the most important advantages of mobile applications in comparison to standard therapy materials. The algorithm of the flashcard system could tailor the exercise plan based on patients’ recent performance. In addition, SLTs could adapt the plan and support the patients to achieve the best possible outcome.

Reminder System

Pop-up messages to remind patients of pending homework, a specific behavioral change or the next session were diversely discussed. Studies show that electronic reminder systems can work in the health sector to support therapy adherence and outcomes (Marcolino et al., 2018; Mbuagbaw et al., 2015; Yasmin et al., 2016). Too many reminders on the other hand have been proven to annoy people, thus achieving the opposite (Franke et al., 2016). As a result, a balanced use of reminders should be considered.

Strengths and Limitations

Many therapeutic apps are currently being created in the process of digitalization. The strength of this development process is the combination of qualitative exploration and software development to ensure the suitability for end users. Despite the availability of different oral-motor therapy apps, none combine as many functions as the described concept nor appeared to follow a scientific approach for their development. Only one other study was identified that describes the design of an Oral Therapeutic Tool for Speech and Feeding Therapies (Nguyen, 2019). It should be noted that our work was focused in Germany, but the concepts should appeal to people working with OMDs in other countries as well.

A small number of patients and relatives were included in the first interview process and Step 5 because of recruiting problems. For organizational reasons, patients under the age of 14 were excluded because the approach for small children would have required a different methodology, which was beyond the scope of this work. The results might therefore reflect the opinions of SLTs more than those of child and adolescent patients This could lead to difficulties during the testing phase. For these reasons, the results must be viewed cautiously in this context. Nevertheless, the app seems promising and is ready for testing in a larger study with additional interviews based on patients’ perceptions.

CONCLUSION

In general, the idea of an app-based exercise tool was considered innovative and beneficial for OMT. The use of apps in the field of SLT shows potential and has gained recognition during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study can serve as a pilot project for the development of an app supporting OMT with focus on content features gathered by potential end users. Technical development and subsequent evaluation of feasibility and effectiveness of this app should be the main goal of further research.

Acknowledgments

The study was conducted in the context of a master’s thesis in the master’s degree program “health services research and implementation science“ (M.Sc.) at the Ruprecht Karls University of Heidelberg. This study was not funded. The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data from this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Abteilung Allgemeinmedizin und Versorgungsforschung. 2017. Standard Transkriptionsregeln für qualitative Inhaltsanalysen Version 1.3.

- Amolto. 2020. Audio & Video recording for Skype & Teams. https://amolto.com/.

- Autodesk, Inc. 2018. Sketchbook. https://sketchbook.com/.

- Benkert, K. K. 1997. The effectiveness of orofacial myofunctional therapy in improving dental occlusion. The International Journal of Orofacial Myology 23: 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilda, K., J. Mühlhaus, and U. Ritterfeld. 2016. Neue Technologien in der Sprachtherapie. Georg Thieme Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, R. M., R. I. Fretz, and L. L. Shaw. 1995. Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fillbrandt, A. 2021. TherapiePad. https://therapiepad.de/?s=Mundmotorik.

- Fischer-Voosholz, M., and U. Spenthof. 2002. Orofaziale Muskelfunktionsstörungen: Klinik - Diagnostik - ganzheitliche Therapie. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, I., S. Thier, and A. Riecher-Rössler. 2016. Effects of an electronic reminder system on guideline-concordant treatment of psychotic disorders. neuropsychiatrie 30, 4: 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, A., S. Rhein, C. Adam, and J. Pumm. 2019. Funktion und Form--MFT und KFO: mykie®--ein erfolgreiches Konzept für gelebte Interdisziplinarität zwischen Kieferorthopädie und Logopädie. Forum Logopädie 33, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, L., M. Morris, T. Serry, and S. Erickson. 2018. Mobile apps for treatment of speech disorders in children: An evidence-based analysis of quality and efficacy. PloS one 13, 8: e0201513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtenbach, M., and W. Wallner. 2009. Myofunktionelle Therapie (MFT) im orofazialen Bereich–praktische und kritische Aspekte aus logopädischer Sicht. Informationen aus Orthodontie & Kieferorthopädie 41, 04: 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gačnik, M., A. I. Starčič, J. Zaletelj, and M. Zajc. 2018. User-centred app design for speech sound disorders interventions with tablet computers. The Information Society 17, 4: 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Play Store. 2021. Oral motor exercises. https://play.google.com/store/apps/collection/cluster?clp=ggEWChRvcmFsIG1vdG9yIGV4ZXJjaXNlcw%3D%3D:S:ANO1ljIaJuw&gsr=ChmCARYKFG9yYWwgbW90b3IgZXhlcmNpc2Vz:S:ANO1ljLCLMk.

- Grabowski, R., F. Stahl, M. Gaebel, and G. Kundt. 2007. Relationship between occlusal findings and orofacial myofunctional status in primary and mixed dentition. Part I: Prevalence of malocclusions. Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics 68, 1: 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homem, M. A., R. G. Vieira-Andrade, S. G. Falci, M. L. Ramos-Jorge, and L. S. Marques. 2014. Effectiveness of orofacial myofunctional therapy in orthodontic patients: a systematic review. Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics 19, 4: 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazantzis, N., C. Whittington, L. Zelencich, M. Kyrios, P. J. Norton, and S. G. Hofmann. 2016. Quantity and Quality of Homework Compliance: A Meta-Analysis of Relations With Outcome in Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Behavior Therapy 47, 5: 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel, A. M. 2014. Myofunktionelle Therapie. Schulz-Kirchner Verlag GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Klocke, A., H. Korbmacher, and B. Kahl-Nieke. 2000. Der Status der myofunktionellen Therapie im Rahmen der interdisziplinären Zusammenarbeit aus der Sicht des Muskelfunktionstherapeuten. Sprache· Stimme· Gehör 24, 01: 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolino, M. S., J. A. Q. Oliveira, M. D’Agostino, A. L. Ribeiro, M. B. M. Alkmim, and D. Novillo-Ortiz. 2018. The Impact of mHealth Interventions: Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. JMIR mhealth and uhealth 6, 1: e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, R. M. 2005. A retrospective and prospective view of orofacial myology. The International Journal of Orofacial Myology 31: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matallaoui, A., J. Koivisto, J. Hamari, and R. Zarnekow. 2017. How effective is “exergamification”? A systematic review on the effectiveness of gamification features in exergames. Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Mbuagbaw, L., S. Mursleen, L. Lytvyn, M. Smieja, L. Dolovich, and L. Thabane. 2015. Mobile phone text messaging interventions for HIV and other chronic diseases: an overview of systematic reviews and framework for evidence transfer. BMC Health Services Research 15: 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilinger, M. 1999. Untersuchung ausgewählter Aspekte myofunktioneller Störungen im Vorschulalter. Herbert Utz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, J. P. 2003. Orofacial Myology – International Perspectives Second Edition. British Dental Journal 195, 6: 355–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nguyen, A. T., G. Weed, and H. S. Narman. 2019. Oral Therapeutic Tool for Speech and Feeding Therapies. Proceedings of the IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM); pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffit, W. R. 1973. Muscle pressures and tooth position. A review of current research. Australian Orthodontic Journal 3, 3: 104–108. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.029382639899778. [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A. K., C. S. Rigby, and R. M. Ryan. 2010. A motivational model of video game engagement. Review of General Psychology 14, 2: 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubMed. 2021. Search results: apps for speech and language therapy. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/?term=(speech and language therapy) AND (mobile application).

- Richter, M., and M. D. Flückiger. 2016. Usability und UX kompakt: Produkte für Menschen. Springer Vieweg. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, L., and C. Wittich. 2014. Evidenzbasierte Behandlung Myofunktioneller Störungen. Forum Logopädie 28, 1: 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., H. Patrick, E. L. Deci, and G. C. Williams. 2008. Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: Interventions based on self-determination theory. The European Health Psychologist 10, 1: 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., C. S. Rigby, and A. Przybylski. 2006. The motivational pull of video games: A self-determination theory approach. Motivation and Emotion 30, 4: 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starke, A., and J. Mühlhaus. 2018. App-Einsatz in der Sprachtherapie-Die Nutzung evidenzbasierter und ethisch orientierter Strategien für die Auswahl von Applikationen in der Sprachtherapie. Forum Logopädie 32, 2: 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, K. 2014. Cognitive behavioral game design: a unified model for designing serious games. Frontiers in Psychology 5: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbi GmbH. 2018. MAXQDA Standard 2018. https://www.maxqda.de/software-inhaltsanalyse?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIkNr1rKDY5QIVyOR3Ch1xpgb7EAAYASAAEgLB5fD_BwE.

- Yasmin, F., B. Banu, S. M. Zakir, R. Sauerborn, L. Ali, and A. Souares. 2016. Positive influence of short message service and voice call interventions on adherence and health outcomes in case of chronic disease care: a systematic review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 16: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, N., J. N. Bailenson, M. Urbanek, F. Chang, and D. Merget. 2007. The unbearable likeness of being digital: The persistence of nonverbal social norms in online virtual environments. CyberPsychology & Behavior 10, 1: 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2021 by the authors. 2021 Christina Osen, Nicola Litke, Michel Wensing, Aline Weis.