Abstract

The purpose of this article is to stimulate research in orofacial myology. The research-to-practice gap may be reduced by highlighting concepts relating to evidence-based practice. Information is also presented on the International Association of Orofacial Myology Institutional Review Board process.

INTRODUCTION

Every treatment session is an opportunity for research. Data are collected. Questions are answered, while additional questions are conceived. Behaviors, phenomena, and structures are investigated. Who better to serve as investigators than clinicians? After all, clinicians are actively practicing in the field. They know the patients’ needs. They are acutely aware of gaps in the evidence, the questions that have yet to be adequately addressed, or even asked. Clinicians recognize that promoting the evidence base is best for their patients, selves, and the discipline.

DISCUSSION

Research promotes change, enhancing what is known, answering the questions for which the answers are unknown, asking the questions previously unstated, and ultimately, improving knowledge, skills, approaches, and behaviors. The quest for additional evidence within a field increases its recognition among other disciplines, corroborating its credibility as being supported by sound, scientific principles (Rothan-Tondeur et al., 2014). Involvement in research, whether direct or indirect, helps clinicians grow and develop as professionals (Rothan-Tondeur et al.). The journey from a clinical question or curiosity to the evidence narrows the research-to-practice gap, and perhaps most importantly, scientific inquiry optimizes the provision and quality of services to patients (Campbell & Douglas, 2017).

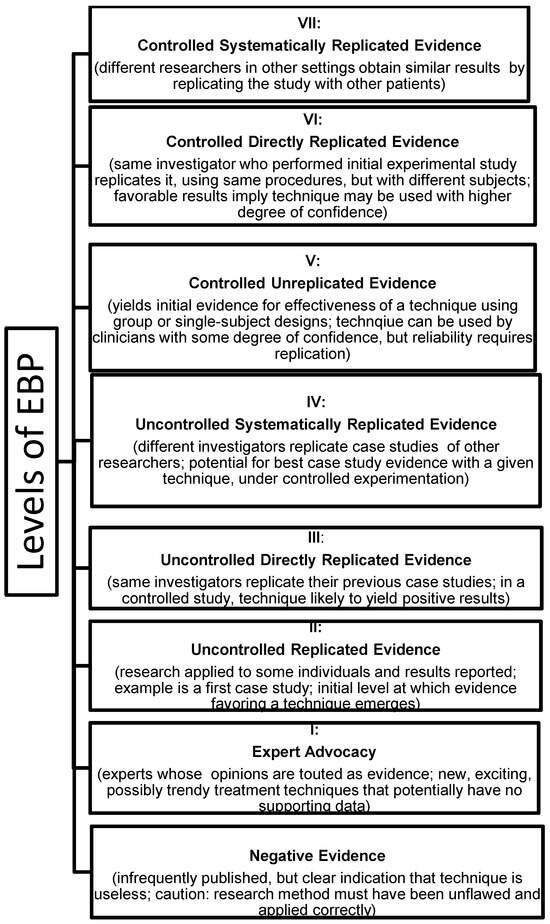

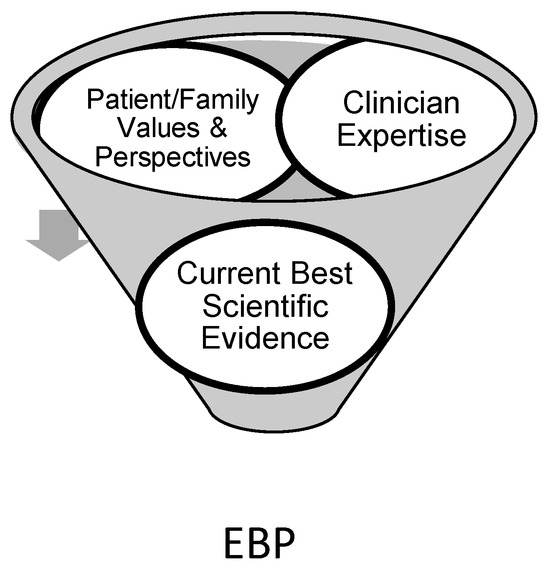

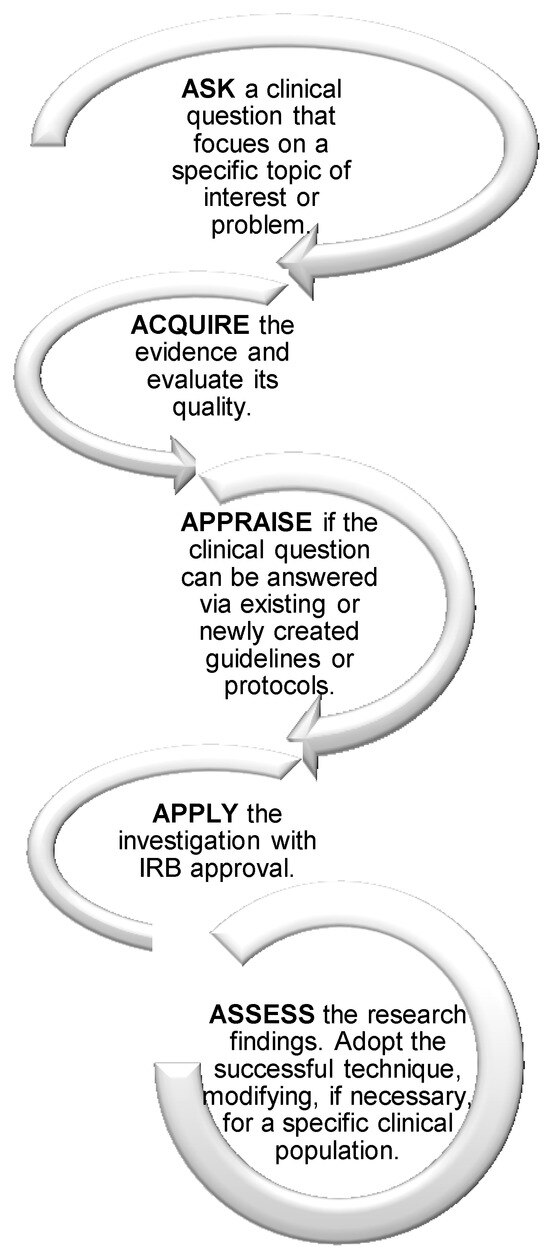

Evidence-based practice, or EBP, is based on the thoughtful integration of the best available evidence, combined with the expertise of clinicians and wishes of the patients and caregivers, all for the purpose of decision-making in patient care (Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes, & Richardson, 1996; University of Louisville School of Dentistry, n. d.). EBP helps address the demands of the public, other disciplines, and third-party reimbursement systems for the best services. While there are many interpretations of EBP, quality care that is effective and efficient is a fundamental goal. See Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The various explanations of EBP have led to considerable debate regarding the nature of evidence (Roulstone, 2011). Clinicians must consider and balance the various, legitimate sources of evidence (Roulstone). For example, randomized controlled trials are often referred to as the “gold standard” for clinical research, but other sources, including qualitative studies, clinician expertise, and patient values and expectations are all necessary for EBP (Roulstone). After all, EBP drives a discipline, propelling it towards better outcomes for all involved. A collective advantage is then revealed for the patient and his/her caregivers, the clinician and his/her colleagues, and the entire profession (Crowe, Masso, & Hopf, 2018; McCabe, 2018).

Figure 1.

LEVELS OF EBP (Hegde & Maul, 2006).

Figure 2.

COMPONENTS OF EBP (adapted from the Cleveland Clinic, 2019).

Figure 3.

PROCESS OF EBP USING THE 5 A’s (ASHA, 2019; Cleveland Clinic, 2019; Hadley, 2010).

Continued efforts in EBP will help the discipline of orofacial myology promote not only research and positive change, but reduce and hopefully minimize the research-to-practice gap. Engaging in research, asking and answering the difficult questions using well-designed studies in real-world environments, however, poses many challenges. These barriers include lack of time and increased daily demands in work settings, insufficient support, lack of confidence in conducting research, with statistical knowledge, and in methodological adequacy, deficient relevant information literacy skills, lack of access to an Institutional Review Board (IRB), hesitation to change attitudes, beliefs, practices, and behaviors, and limited adoption of empirically-supported practices (Campbell & Douglas, 2017; Crowe, Masso, & Hopf, 2018; McCabe, 2018; Nail-Chiwetalu & Bernstein-Ratner, 2007; O’Connor & Pettigrew, 2009; Vallino-Napoli & Reilly, 2009). Of these impediments, lack of time is often cited as the most significant challenge (Campbell & Douglas, 2017; O’Connor & Pettigrew, 2009; Vallino-Napoli & Reilly, 2009).

Ultimately, orofacial myologists will need to examine and recognize the positive and negative aspects of their work in order to adopt and adhere to EBP, but this can be actualized. The International Association of Orofacial Myology (IAOM) is implementing its own IRB in order to help address the challenges of EBP and bridge the research-to-practice gap. An IRB is a committee within a university, hospital, or organization that reviews research proposals by its employees or members (American Psychological Association, [APA] 2019). The IRB reviews proposals prior to requests for funding of the research and/or conduction of the research to ensure compliance with ethical principles and federal regulations for the protection of the rights and welfare of human subjects (APA; Oregon State University Research Office, 2019). The IRB has the authority to approve, disprove, or require modifications to projects (APA).

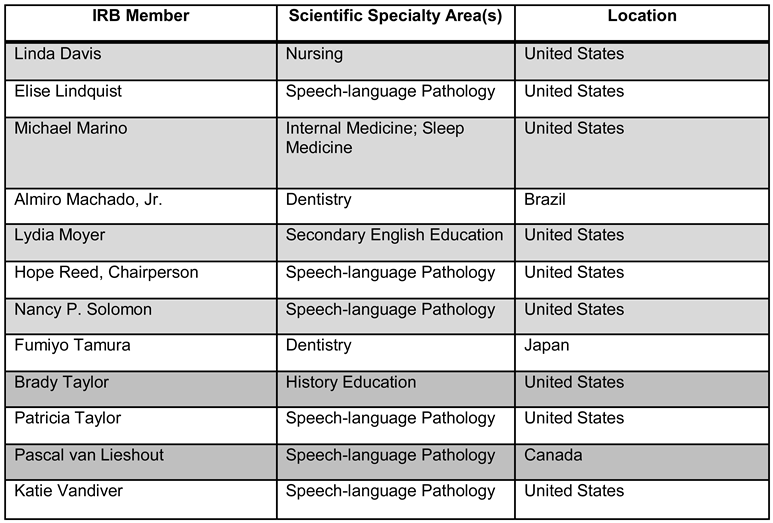

IAOM’s IRB is registered with the United States Department of Health and Human Services Office for Human Research Protections, demonstrating the capability to completely and sufficiently review human research-related proposals and their potential institutional, legal, scientific, and social implications (Oregon State University Research Office). A roster of the IAOM IRB members is provided in the Appendix.

In order for a proposed study to be approved by an IRB, there are six criteria that must be met. (1) Risks to human subjects are minimized. (2) Risks to human subjects are reasonable in relation to the anticipated benefits, if any, to subjects, and the importance of the knowledge expected to be gained as a result of the proposed investigation. (3) Selection of participants is equitable. (4) Informed consent is sought from each prospective participant or the participant’s legal representative and appropriately documented in accordance with and to the extent of local, state, and federal regulations. (5) Where appropriate, the research proposal adequately provides for monitoring the data to be collected to ensure the safety of participants, including provisions for the protection of privacy and maintaining confidentiality of data. (6) When some or all participants belong to vulnerable populations, such as children, pregnant women, prisoners, persons with impaired decision-making abilities, and persons who are intellectually, educationally, and/or economically disadvantaged, additional safeguards are included in the proposed investigation and IRB process to protect their rights and welfare (Common Rule, 2018; University of California at Berkeley Office for Protection of Human Subjects, 2019).

Ultimately, the aim is to protect all human subjects. More specifically, the goal is to safeguard informed consent, patient confidentiality and personally identifying information, vulnerable populations, researchers, and the discipline of orofacial myology.

The IAOM IRB was established to encourage research among orofacial myologists who do not have access to an IRB through their work setting. For example, orofacial myologists who work in universities and hospitals must apply to the IRBs housed within those institutions, not to the IAOM IRB. Also, some school districts may house an IRB. However, many private practice-based clinicians do not have access to an IRB. Therefore, they must pay rather costly fees to apply to an independent IRB. The IAOM IRB was established to better serve its members as a value-added benefit of membership and to promote their engagement in research activities. If a clinician works in a setting where an IRB exists, then that individual must apply to that respective IRB. The IAOM IRB is solely for IAOM members who are working in a setting without an IRB. The application materials and Policies and Procedures Manual (IAOM, 2019) will soon be available via a password-protected area of the IAOM Website.

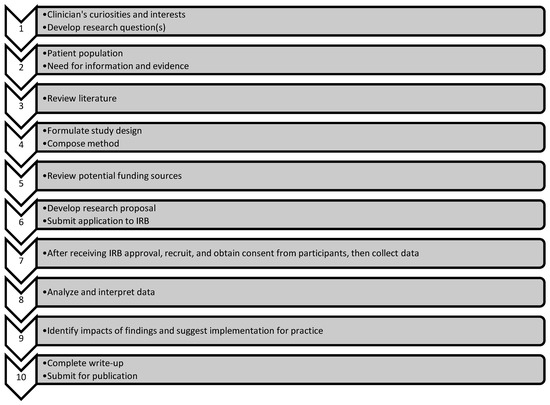

Figure 4.

STEPS IN THE RESEARCH PROCESS (adapted from Aspergillus & Aspergillosis, 2004).

Figure 5.

LEVELS OF REVIEW FOR PROPOSALS MADE TO THE IAOM IRB (IAOM, 2019).

Future recommendations include investigations that enhance the evidence base, specifically those that address treatment efficacy. The establishment of a negative evidence database is also suggested, because knowing what approaches have not yielded success is as important as knowing which ones have proven effective. A record of negative evidence is necessary for the sake of patients, clinicians, and the entire discipline.

Lastly, a practice portal and evidence maps like those of ASHA for speech-language pathologists are recommended.

Who better to perform the necessary research than clinicians? Clinicians see the problems, gaps in the evidence, and need for solutions in daily practice. They work directly with patients and caregivers. They have a natural curiosity. A noteworthy goal is to have experienced clinicians intersect with the desire and ability to pursue the evidence.

APPENDIX

IAOM IRB Roster.

References

- American Psychological Association (APA). Frequently asked questions about Institutional Review Boards. 2019. Available online: https://www.apa.org/advocacy/research/defendingresearch/review-boards.

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). Evidence-based practice. 2019. Available online: https://www.asha.org/Research/EBP/Evidence-Based-Practice/.

- Aspergillus; & Aspergillosis. Research process flowchart. 2004. Available online: https://www.shoulderdoc.co.uk/documents/research_flowchart.pdf.

- Campbell, W. N.; Douglas, N. F. Supporting evidence-based practice in speech-language pathology: A review of implementation strategies for promoting health professional behavior change. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention 2017, 11, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland Clinic. Evidence-Based Practice: Nursing: What is EBP? 2019. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.libguides.com/nursingebp.

- Common Rule 45 C.F.R. § 46-111. 2018.

- Crowe, K.; Masso, S.; Hopf, S. Innovations actively shaping speech-langauge pathology evidence-based practice. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2018, 20, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, A. J. Evidence-based practice tools for busy practitioners. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Philadelphia, PA, November; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hegde, M. N.; Maul, C. A. Language disorders in children: An evidence-based approach to assessment and treatment; Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Orofacial Myology (IAOM). Policies and procedures manual: Institutional Review Board (IRB); Sequim, WA: Author, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, T. How do we change our profession? Using the lens of behavioural economics to improve evidence based practice in speech-language pathology. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2018, 20, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nail-Chiwetalu, B.; Bernstein-Ratner, N. An assessment of the information seeking abilities and needs of practicing speech-language pathologists. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2007, 95, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, S.; Pettigrew, C. M. The barriers perceived to prevent the successful implementation of evidence-based practice by speech and language therapists. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 2009, 44, 1018–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oregon State University Research Office. What is the Institutional Review Board (IRB)? 2019. Available online: https://research.oregonstate.edu/irb/frequently-asked-questions/what-institutional-review-board-irb.

- Rothan-Tondeur, M.; Courcier, S.; Béhier, J. M.; Participants of round table N1 of Giens XXIX; Leblanc, J.; Peoch, N.; Thoby, F. Promoting the place of the allied health professions in clinical research. Therapie 2014, 69, 271–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roulstone, S. Evidence, expertise, and patient preference in speech-language pathology. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2011, 13, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackett, D. L.; Rosenberg, W. M.; Gray, J. A.; Haynes, R. B.; Richardson, W. S. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal 1996, 312, 71–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of California at Berkeley Office for Protection of Human Subjects. Criteria for IRB approval of research. 2019. Available online: https://cphs.berkeley.edu/checklists_worksheets/approval.pdf.

- University of Louisville School of Dentistry. Evidence-based practice. n.d. Available online: https://louisville.edu/dentistry/academicaffairs/evidence-based-practice.

- Vallino-Napoli, L. D.; Reilly, S. Evidence-based health care: A survey of speech pathology practice. Advances in Speech Language Pathology 2009, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. 2019 Hope C. Reed