Abstract

Atypical deglutition (tongue thrust swallowing) has been thought by some to be an etiological factor related to dental malocclusion, especially changes related to excessive increase in vertical facial growth. The purpose of this study was to investigate this possible relationship between atypical deglutition and vertical facial growth by documenting the lower, middle and upper facial areas of children with atypical deglutition. 55 lateral cephalometric radiographs were analyzed and measured in each of two groups of subjects according to standardized facial plane angles between the (I) palatal plane and mandibular plane, (II) palatal plane and occlusal plane, (III) mandibular plane and occlusal plane, (IV) skull base and Frankfurt plane, and (V) mandibular angle. The experimental group was comprised of 55 subjects with atypical deglutition, while 55 subjects with normal swallowing were used as a control group. The linear/angular measurements were subjected to Mann-Whitney statistical test with a significance level of 5%. Results: The average angle of the variables I, II, III and IV are, respectively: 29, 14, 14 and 9 degrees in both groups. There were no significant differences in the variables studied in the normal and atypical swallowing groups. However, for variable V there were 3 degrees of difference between the groups, which was statistically significant. The results of this study suggest that the problem of atypical swallowing may be of functional origin and not associated with anatomical changes seen in vertical growth patterns.

INTRODUCTION

Under normal neurological conditions, and in order to maintain extra-uterine life, the functions of respiration, sucking and deglutition of newborn are already established at the time of birth. At the first occasion when neonates encounter their mother’s breast, they should be capable of sucking and swallowing. At this stage of development, the tongue has a large volume, occupies the entire oral cavity and can perform posteroanterior movements within the gingival rim. With the eruption of the first deciduous teeth and the physiological advancing of the mandible, the consistency of food in children’s diets needs to be gradually increased. Thus, sucking is replaced by an impulse to bite and, later on, to chew.

Childlike deglutition, with the tongue occupying the entire intraoral space in association with contraction of the perioral musculature, usually has evolved into mature deglutition by the start of the mixed dentition stage. For a variety of reasons that so far remain incompletely explained, childlike (or infantile) deglutition may persist beyond the replacement of the deciduous teeth. Such deglutition is classified as atypical (Peng et al., 2004).

Some authors believe that atypical deglutition may be attributed to sucking without nutritive purposes, use of feeding bottles, oral respiration, abnormalities of the central nervous system, and anatomical abnormalities (Bertolini, et al., 2003; Cayley et al., 2000; Cheng, 2002). However, there is no consensus regarding the etiology of atypical deglutition.

The relationship between craniofacial morphology and extrinsic factors which have an influence on the development of the face, has been arousing great interest among researchers (Cayley et al., 2000). Empirically it is believed that in the cases of atypical swallowing there is a tendency to increase the vertical dimensions of the face, although this possible alteration is not considered a cause or a consequence of atypical swallowing. Studies have investigated the influence of atypical swallowing on the craniofacial pattern and on orofacial morphology (Mason, 1988; Proffit, 1986), especially of the facial vertical dimensions, but there is no consensus among researchers.

PURPOSE

Therefore the objective of this study was to document selected vertical components of the lower, middle, and upper face of children with atypical deglutition to determine whether there are changes in the vertical dimension that can be associated with a tongue thrust swallowing pattern.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This was a retrospective, analytical, observational and cross-sectional cohort study in which lateral teleradiographs (cephalograms) from children of both sexes at the phase of mixed dentition were evaluated. These children were treated between January 2006 and December 2007 at the dental clinic that formed part of the refresher course on functional orthopedics of the maxillae, run by the Systemic Dentistry Society of São Paulo.

All lateral view teleradiographs selected for the present study were 18x24cm in size and were obtained using the same Siemens apparatus in one second at 6 kVp with a focal length of 1.5 meters. The examinations were performed with the patient’s head in a natural position (mirror position), performed by the same examiner. Using the selected lateral teleradiographs, cephalometric examination was performed in a darkened room with a negatoscope. An acetate sheet was laid over the teleradiograph and the following anatomoradiographic points and planes were marked on the sheet: angles between (I) palatal plane and mandibular plane, (II) palatal plane and occlusal plane, (III) mandibular plane and occlusal plane, (IV) base skull and Frankfurt plane, and (V) mandibular angle into two groups.

Lateral teleradiographs that did not provide a good view of the anatomical structures used in the cephalometric examination were excluded from the study sample. Patients with dental agenesis, congenital poor orofacial formation, orthodontic and/or functional orthopedic treatment prior to the study, or where there was imprecision regarding the diagnosis of deglutition were also excluded.

Tongue functions were examined by senior orthodontists, who used the forced-opening method to identify swallowing patterns in the following manner. The movements of the tongue during swallowing may be clinically assessed, asking the child to swallow liquids, semi-solids or solids or even only saliva to observe the protrusion of the tongue with the lips half-open or, if necessary, with lips opened with the fingers (forced opening method). By placing the hands on the masseters it is possible to observe the presence or absence of contraction and to observe the ascendant movement of the hyoid bone under the thyroid cartilage. The participation of the perioral muscles is also observed, as well as whether the swallowing is loud, if there is a retraction movement with the head, the presence of any signal which characterizes child swallowing. (Peng et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2004; Ovsenik et al., 2007)

Twenty lateral teleradiographs of 20 patients with a clinical diagnosis of atypical deglutition and another 20 lateral teleradiographs of 20 subjects with normal deglutition were selected for a pilot study to calculate the sample size in which the standard deviation of the control group and the difference between the means of the control and experimental groups were calculated. At a significance level of 0.05, 110 teleradiographs (i.e. 55 in each group) were required to achieve a test power of 0.10. After sample size estimation, the whole sample was selected using the same criteria employed in the pilot study, as described above.

The lateral teleradiographs from the experimental group and the control group were randomly assigned and numbered sequentially so that the examiner performing the manual measurements was blinded to patient data. In an attempt to minimize systematic errors, the same examiner carried out data collection of the whole sample on two occasions separated by a 20-day interval.

After the collection of radiographic data, age and sex data were assessed, along with whether or not atypical deglutition was present. To compare angular measurements between the two groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Descriptive data were presented as mean standard deviation and range, and the significance levels of the test results were estimated.

For this study two reference planes were used which were believed to be minimally influenced by extrinsic factors of facial growth: the cranial base, and the Frankfurt plane. A possible linear association between pairs of variables (correlations) was investigated using Spearman’s correlation analysis. To investigate the intra-examiner consistency, the Wilcoxon test for related samples was used to detect possible differences between measurements obtained on two different occasions. The significance level used in the statistical tests was 5%.

Since this was a retrospective study using lateral teleradiographs from patient files whose treatment had been completed, and because the study did not involve carrying out experiments on human beings, it was deemed unnecessary to obtain written informed consent from the patients. On the other hand, all appropriate measures were taken to ensure confidentiality of the subjects’ personal data. The research protocol for this study received unrestricted prior approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Medical Sciences, Unicamp (#619/2005).

RESULTS

The study sample consisted of 110 lateral teleradiographs from 52 female and 58 male subjects. The two groups were similar with regard to gender distribution. The mean age of the control group (normal deglutition) and the experimental group was 9.46 years and 10.05 years, respectively, without any significant difference between the groups.

Data were collected by the same examiner on two occasions in an attempt to minimize systematic errors. The evaluation of data revealed no significant differences between the two measurements, confirming intra-examiner consistency of the method. A nonparametric statistical analysis (Mann-Whitney U test) was used because of the irregular distribution of the sample data.

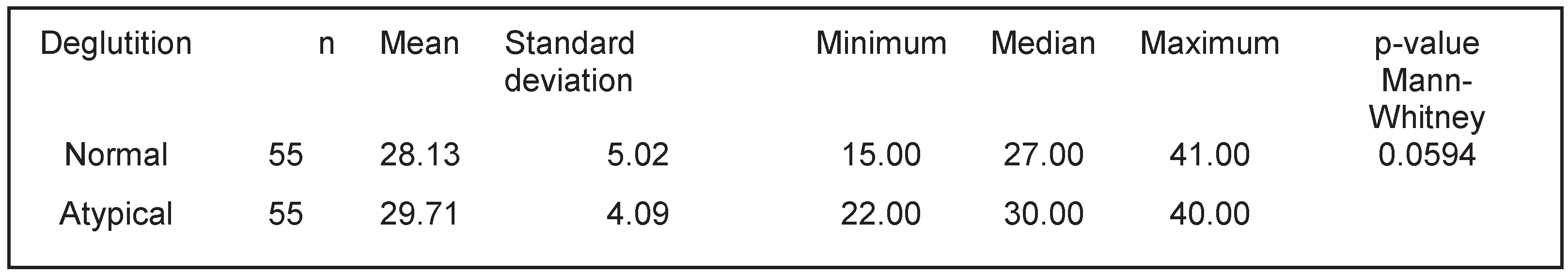

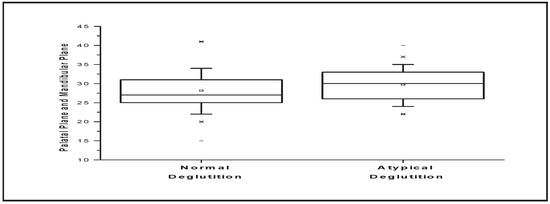

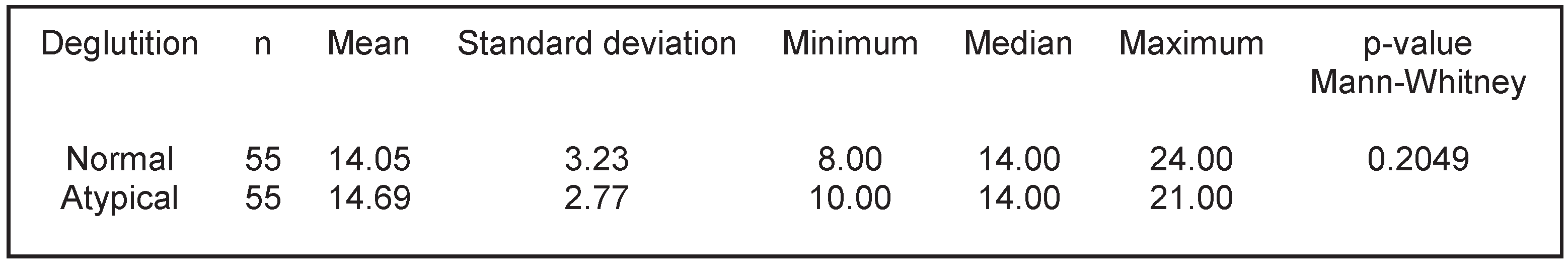

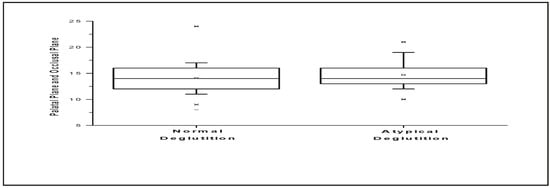

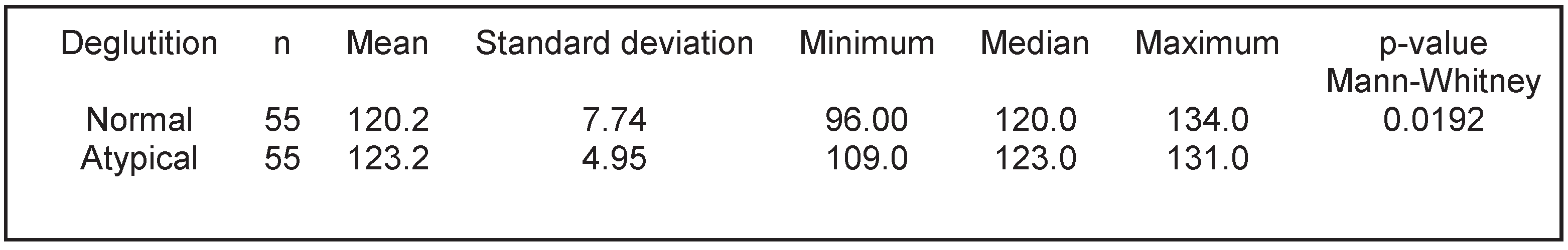

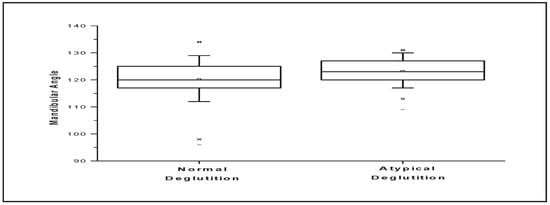

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the two groups with regard to cephalometric measurements. The average angle of the variables I, II, III and IV are respectively 29, 14, 14 and 9 degrees in both groups. No significant differences in the variables studied in groups of normal and atypical swallowing. However, for variable V there were 3 degrees of difference between the groups, with statistical significance. (p-value=0.0192)

A significant difference for variable IV was not found among the groups which were studied. However, a negative correlation for variable IV with the mandibular angle variable (V) was observed only in the control group.

To investigate the linear association between pairs of variables, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used. In the group with normal swallowing a positive correlation between variables I and II has been found. There was also a positive correlation with variables I and III. However, in the group with atypical swallowing there was a positive correlation only between variables I and III, and variables I and V.

An interesting finding from this study was the fact that variable V presents a positive correlation with variables I and II in the group with normal swallowing, but in the group with atypical swallowing this correlation is only observed between variables V and I, that is, there was no correlation between variables V and III in the groups with atypical swallowing.

In spite of the fact that the mandibular angle is increased in the group with atypical swallowing and that this variable contributes to the increase of variable I (the angle formed by the mandibular plane and the palatal plane), there is no increase of variable III (angle formed by the mandibular plane and the occlusal plane).

To investigate the intra-examiner consistency, a Wilcoxon test for related samples was used to detect possible differences between measurements obtained on two different occasions. However, no significant difference was found between these two measurements.

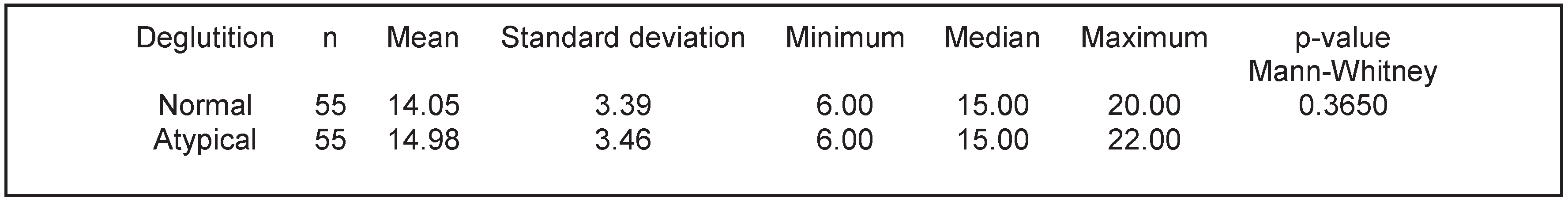

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of angles between the palatal plane and mandibular.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of angles between the palatal plane and mandibular.

|

Figure 1.

Comparative analysis of angles between the palatal plane and mandibular plane.

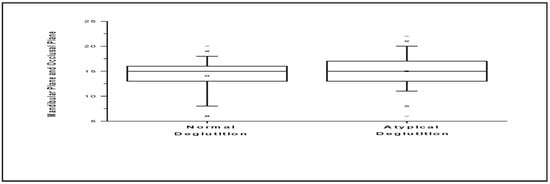

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of angles between palatal plane and occlusal plane.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of angles between palatal plane and occlusal plane.

|

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of angles between palatal plane and occlusal plane.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of angles between mandibular plane and occlusal plane.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of angles between mandibular plane and occlusal plane.

|

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of angles between mandibular plane and occlusal plane.

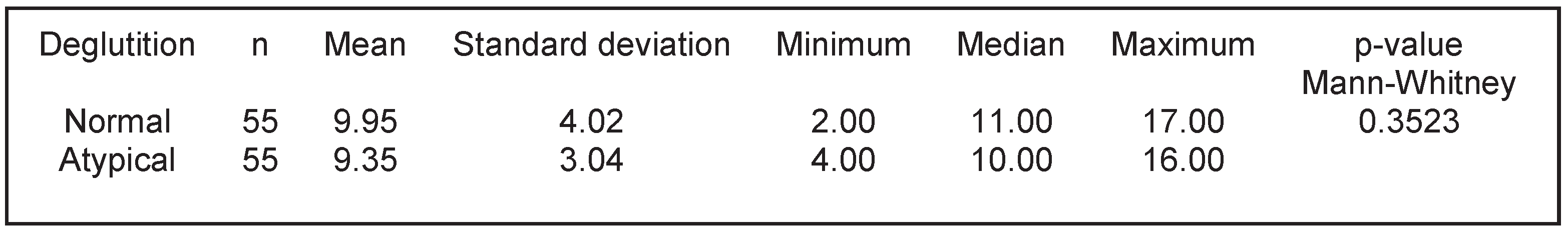

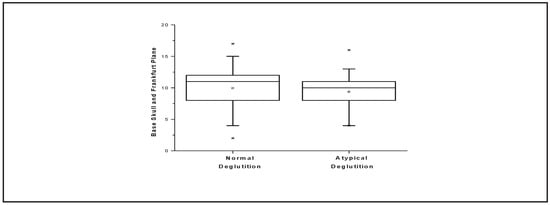

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of angles between skull base and Frankfurt plane.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of angles between skull base and Frankfurt plane.

|

Figure 4.

Comparative analysis of angles between skull base and Frankfurt plane.

Table 5.

Comparative analysis of mandibular angle.

Table 5.

Comparative analysis of mandibular angle.

|

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis of mandibular angle.

DISCUSSION

Interest in the further study of atypical deglutition continues due to many gaps in the literature on this topic. Appealing study topics include the expansion of the classifications of deglutition (Bertolini et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2004); the causes of atypical deglutition and its consequences (Cheng et al., 2002; Fujiki et al., 2004); diagnostic methods (Cayley et al., 2000; Kikyo et al., 1999); age at its onset, and treatment methods.

Deglutition is a highly complex and coordinated function, requiring activation of many anatomical structures related to the tongue. Insufficient functional stimulation of the stomatognathic system, especially involving the tongue, may evolve as the main factor linked to the persistence of childlike/infantile patterns of deglutition.

A variety of instrumental techniques are available for diagnosing atypical deglutition. Prominent among the methods that have been used for diagnosis during the oral phase of deglutition is videofluoroscopy. This instrumentation has limited availability in dental practice since the equipment is usually a part of hospital-based radiology departments. The evaluation of the images obtained by videofluoroscopy involves rather subjective assessments (Cayley et al., 2000; Kikyo et al., 1999; Peng et al., 2004), however, the multiple views of swallows, involving the frontal, lateral, and coronal dimensions, provide useful descriptions of the mechanical properties of deglutition.

Teleradiographs are standardized extraoral images that are routinely used as an orthodontic/orthopedic functional diagnostic tool (Malkoc et al., 2005). Teleradiography has been used in a large number of studies on craniofacial growth (Pae et al., 2008; Sheng et al., 2009). Through this method, the spatial relationships between the cranium, vertebrae, mandible, and hyoid bone can be easily examined (Bibby and Preston, 1981; Bibby, 1984; Rocabado, 1983; Stpovich, 1965).

This radiographic study evaluated the relationships between known parameters, but these relations were used in a novel manner in that they were correlated with normal and abnormal deglutition. In addition to studying a normal group, this study also evaluated patients with atypical deglutition: a quite prevalent clinical condition that can impact orofacial, nutritional, esthetic, and psychosocial development.

While results from this current study are similar to studies that demonstrate alterations in the vertical dimensions of patients with orofacial myofunctional disorders, results from this study do not confirm that any changes in orofacial vertical dimensions are the result of atypical swallowing. The results presented in this study indicated that only variable V (mandibular angle) showed a difference that had statistical significance. The authors believe that this variable is the first to undergo a growth change related to posture or function, although there are other variables such as time, frequency and intensity of the alteration of swallowing which may possibly contribute to some orofacial change. Labial activity may be another variable, (not studied in this research), which could influence the results. Since there is a close relationship between lingual and labial activities, poor labial positioning and functioning can often account for an atypical positioning and functioning of the tongue.

In the view of the authors, the term ‘atypical deglutition’ is too general and lacking in specificity to adequately describe various types of alterations in the oral phase of swallowing. A host of other contributing variables that can accompany a tongue thrust swallow pattern may better account for any changes in the vertical dimensions of the face. Such variables may include: the resting position of the tongue; the vertical extent of lip incompetence; the size and configuration of tonsils and adenoids; dental arch width; and the presence of an anterior open bite.

Studies that have documented the abnormal forward position of the tongue at rest have established a link with the development of selected malocclusions. A forward resting tongue position can lead to vertical changes in the orofacial complex involving the continued eruption of permanent teeth (Mason, 1988; Proffit, 1986). Vertical changes were not detected in this study that correlated with the single variable of atypical deglutition. The lack of orofacial vertical growth changes in the presence of a tongue thrust swallow pattern suggests that there is a significant difference between the short period involved in a tongue thrust swallow as compared to the much longer duration associated with a forward rest position of the tongue. There is a need to fully describe the influence of many additional orofacial variables that may cause growth changes in the vertical dimension where there is a forward rest posture of the tongue. Such variables would include the size and status of tonsils and adenoids, the position of the hyoid bone, the status of the nasal airway, history of allergic rhinitis, and the dimensions of the oral cavity.

In this study of cephalometric findings on subjects with atypical deglutition, a single angular measurement was linked to the atypical swallowing group. This finding encourages the study of additional physical variables, as well as specific components linked with swallowing such as time, frequency, intensity, and labial action.

This analysis causes the authors to reaffirm that there are intrinsic factors which control the mandibular angle growth, but there are extrinsic factors, among them swallowing, which are capable of minimizing or potentiating these intrinsic growth factors.

The observation of the results of this study confirms a view already known: that the interposition of the tongue during swallowing, as a singular variable, does not influence the vertical orofacial morphology. Since this was a retrospective study based on teleradiographic analysis, a limitation of this study is that it was not possible to assess whether the measurements studied changed after correction of the deglutition disorder.

Although this study focused on functional orthopedics aspects of the issue, the authors believe that this is a multidisciplinary topic involving orthodontics, pediatric dentistry, speech therapy, otorhinolaryngology, and pediatrics. However, an important question remains unanswered: Is this alteration the cause or the consequence for atypical deglutition? Although studies providing information to answer that question are not currently available, the authors believe that due to the complexity of the structures involved in the process of swallowing this alteration is an adaptation to atypical swallowing.

Therefore, the authors propose the increase on variable V (mandibular angle) in the group with atypical swallowing is an additional characteristic of this behavior and not its etiology. The authors suggest further studies are needed to evaluate possible differences in resting tongue posture in different types of atypical swallowing patterns.

The method proposed and used in the present study may help to identify new modalities to treat atypical deglutition, since it increases the possibility of achieving an objective diagnosis for this functional abnormality. Moreover, this methodology may be used in other studies, thereby creating favorable conditions for diagnosing abnormalities of facial bone growth and development resulting from functional deviations, which are harmful to the stomatognathic system. Among these deviations are oral respiration and non-nutrative sucking habits, which present a very close relationship with the functional changes that cause atypical deglutition and they are harmful oral habits. Therefore the results of this study suggest that the problem of atypical swallowing may be of functional origin and not due to anatomical changes caused by vertical growth tendency.

CONCLUSIONS

Conclusions based on the results obtained by this study include:

- Variables (I) palatal plane and mandibular plane, (II) palatal plane and occlusal plane, (III) mandibular plane and occlusal plane, (IV) base skull and Frankfurt plane do not differ significantly among the groups which were studied.

- Variable V mandibular angle presents a statistical significant difference among the groups which were studied.

- Variable V mandibular angle presents a significant positive correlation with variables I palatal plane and mandibular plane and III mandibular plane and occlusal plane from the control group.

- Variable V mandibular angle presents a significant positive correlation with variable I palatal plane and mandibular plane from the experimental group.

- Variable V mandibular angle presents a significant negative correlation with variable IV base skull and Frankfurt plane from the control group.

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank the Foundation for Coordination of Advancement of University-level Personnel (Fundação Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior; CAPES), Brazil for financial support. This article was based on a doctoral thesis in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, School of Medical Sciences, State University of Campinas, Brazil

References

- Bertolini, M M, S Vilhegas, and J R Paschoal. 2003. Cephalometric evaluation in children presenting adapted swallowing during mixed dentition. International Journal Orofacial Myology 29: 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, R E, and C B Preston. 1981. The hyoid triangle. American Journal of Orthodontics 80: 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, R E. 1984. The hyoid bone position in mouth breathers and tongue thrusters. American Journal Orthodontics 85: 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cayley, A S, A P Tindal, W J Sampson, and A R Butcher. 2000. Electropalatographic and cephalometric assessment of myofunctional therapy in open-bite subjects. Australian Orthodontics Journal 16: 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C F, C L Peng, H Y Chiou, and C Y Tsai. 2002. Dentofacial morphology and tongue function during swallowing. American Journal Orthodontics Dentofacial Orthopedics 122: 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, M J P C, D F Nouer, J R Teixeira, and F Berzin. 2007. Cephalometric assessment of the hyoid bone position in oral breathing children. Brazilian Journal Otorrynolaryngology 73: 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki, T, M Inoue, S Miyawaki, and T Nagasadi. 2004. Relationship between maxillofacial morphology and deglutitive tongue movement in patients with anterior open bite. American Journal Orthodontics Dentofacial Orthopedics 125: 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, C A A N. 1983. Hyoid bone’s cephalometric positional study in normal and in malocclusion patients. Revista Odontologia Unesp 12: 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Graber, T M Rakosi. 1985. Dentofacial orthopedics with functional appliances. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby Company, pp. 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Jamielson, A, C Guilleminault, M Partinem, and M A Quera-Salva. 1986. Obstructive sleep apneic patients have cranimandibular abnormalities. Sleep 9: 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikyo, T, M. Saito, and M Ishikawa. 1999. A study comparing ultrasound images of tongue movements between open bite children and normal children in the early mixed dentition period. Journal Medical Dental Science 46: 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Mays, K A, J B Palmer, and K V Kuhlemeir. 2009. Influence of Craniofacial Morphology on Hyoid Movement: A Preliminary Correlational Study. Dysphagia 24: 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Malkoc, S, S Usumez, M Nur, and C E Donaghyd. 2005. Reproducibility of airway dimensions and tongue and hyoid positions on lateral cephalograms. American Journal Orthodontics Dentofacial Orthopedics 128: 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, R. 1988. Orofacial myology: Current trends [Special Issue]. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, T, and M Kanazawa. 1994. Positional change of the hyoid bone at maximal mouth opening. Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology 77: 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovsenik, M, F M Farcnik, M Korpar, and I Verdenik. 2007. Follow-up study of functional and morphological malocclusion trait changes from 3 to 12 years of age. European Journal of Orthodontics 29: 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pae, E K, C Quas, J Quas, and N Garrettd. 2008. Can facial type be used to predict changes in hyoid bone position with age? A perspective based on longitudinal data. American Journal Orthodontics Dentofacial Orthopedics 134: 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C L, P G Jost-Brinkmann, N Yoshida, R R Miethke, and C T Lin. 2003. Differential diagnosis between infantile and mature swallowing with ultrasonography. European Journal of Orthodontics 25: 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C L, P G Jost-Brinkmann, N Yoshida, H H Chou, and C T D Lin. 2004. Comparison of tongue functions between mature and tongue-thrust swallowing—an ultrasound investigation. American Journal Orthodontics Dentofacial Orthopedics 125: 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proffit, W R & Mosby. 1986. Contemporary Orthodontics. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, R, C Guillerminault, J Herran, and N Powell. 1983. Cephalometric analyses and flow-volume loops in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep 6: 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocabado, S M. 1983. Biomechanical relationship of the cranial cervical and hyoid regions. Journal Cranomandibular Practice 3: 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C M, L H Linb, Y Suc, and H H Tsaid. 2009. Developmental changes in pharyngeal airway depth and hyoid bone position from childhood to young adulthood. Angle Orthodontics 79: 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepovich, M L. 1965. A cephalometric positional study of the hyoid bone. American Journal Orthodontics 51: 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsaia, H H, C Y Hob, P L Leec, and C T Tand. 2007. Cephalometric analysis of nonobese snorers either with or without obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Angle Orthodontics 77: 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2010 by the author. 2010 Almiro J. Machado Júnior, Agricio N. Crespo