Orofacial Myofunctional Disorders in Children with Asymmetry of the Posture and Locomotion Apparatus

Abstract

:NTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Orthopedic records

- Open mouth rest posture

- Tongue dysfunction

- Incompetence of lips

- Habit history

- Articulation disorders

- Reclined head position

Statistical analysis

RESULTS

Orthopedic findings

Orofacial myofunctional disorders

Correlations between myofunctional disorders and orthopedic findings

Correlations within myofunctional disorders

DISCUSSION

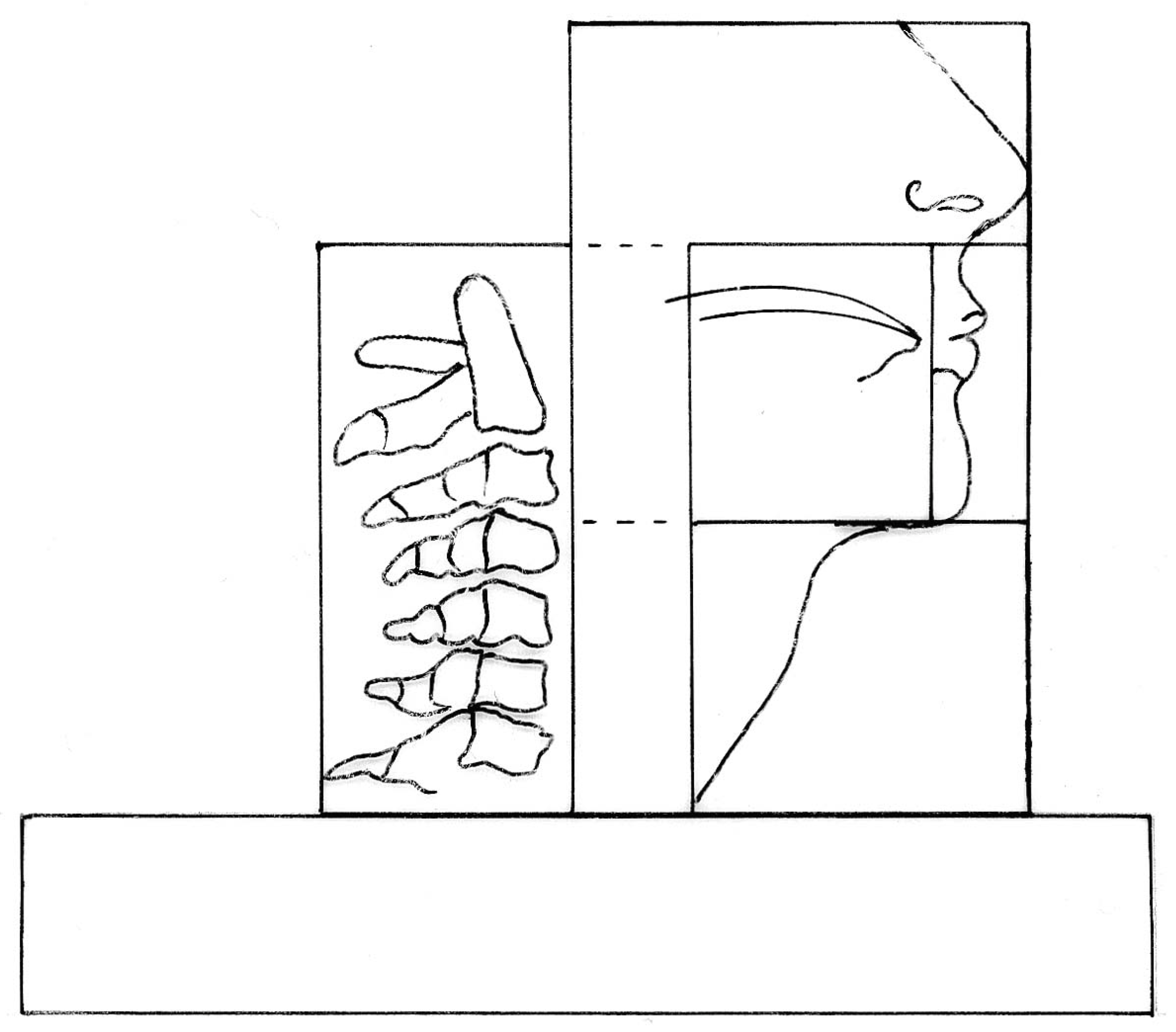

- NASAL CAVITY AND NASAL SINUSES (plus EPIPHARYNX):

- with the important role of habitual nose breathing (respiration)

- LIPS: entrance of the mouth. Play an important role in nasal respiration, tongue position, and incisor inclination.

- ORAL CAVITY with TONGUE and TEETH (plus MESO- and HYPOPHARYNX) : swallowing, mastication and speech are the three major functions within this box.

- INFRA- AND SUPRAHYOID

- MUSCLES: contribute to the orthostatic equilibrium of the lower part of the skull

- OCCIPITO-CERVICAL REGION:

- stabilization and movement of the head

- GENERAL MUSCLE TONUS: body

- posture defined by muscle strength

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- The high prevalence of orofacial dysfunctions in children with orthopedic disorders implies an interaction between form and function.

- As a multifactorial pathology seems to be the most likely explanation for postural alterations, an interdisciplinary treatment approach is essential for success.

- Early multidisciplinary screening in children with respect to posture, orofacial function and orthopedic alterations may help prevent a disturbed orofacial development and dispense with further cost- intensive treatment approaches. The balance of form and function within the orofacial region must be guaranteed as early as possible in order to allow the growth and developmental processes in the orofacial region and the vertebral column to continue in a normal physiological manner.

- Further research is needed to explore causes and effects in orofacial development.

References

- Bahnemann, F. 1981. Über das Mundatmungs-Syndrom und seine Bedeutung in der Zahn-, Mund-und Kieferheilkunde. Quintessenz 32: 519–524. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini, M. M., and J. Z. Paschoal. 2001. Prevalence of adapted swallowing in a population of school children. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 27: 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkert, K. K. 1997. The effectiveness of orofacial myofunctional therapy in improving dental occlusion. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 23: 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigenzahn, W., L. Fischman, and U. Mayrhofer-Krammel. 1992. Myofunctional therapy in patients with orofacial dysfunctions affecting speech. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica 44: 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garetto, Al. 2001. Orofacial myofunctional disorders related to malocclusion. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 27: 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, G. 1981. Funktionelle Pathologie und Klinik der Wirbelsäule. In Bd 1: Die Halswirbelsäule. Teil 1: Die funktionsanalytische Röntgendiagnostik der Halswirbel und der Kopfgelenke. Fischer, Stuttgart. [Google Scholar]

- Hellsing, E., and P. L’Estrange. 1987. Changes in lip pressure following extension and flexion of the head and changed mode of breathing. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 91: 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberman-Krakauer, L., and A. Guilherme. 2000. Relationship between mouth breathing and postural alterations of children: A descriptive analysis. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 26: 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggare, J. A. V., and M. Tellero Laine-Alava. 1997. Nasorespiratory function and head posture. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 112: 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellum, G. D., A. M. Gross, S. T. Hale, S. Eiland, and C. Williams. 1994. Thumbsucking as related to placement and acoustic aspects of /s, z /and lingual rest postures. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 20: 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, L. E., H. Korbmacher, and B. Kahl-Nieke. 2003. Messmethode zur Darstellung der isolierten Kopfgelenkbeweglichkeit bei Kindern und Erwachsenen. Manuelle Medizin 41: 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbmacher, H., and B. Kahl-Nieke. 2001. Optimizing interdisciplinary cooperation for patients with orofacial dysfunctions. Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics 62: 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchesan, I. Q., and L. R. Huberman-Krakauer. 1996. The importance of respiratory activity in myofunctional therapy. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 22: 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesan, I. Q. 2000. The speech pathology treatment with alterations of the stomatognathic system. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 26: 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthiass, H. H. 1966. Probleme der Haltungsbeurteilung. Lohmann. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, P. G. 2000. Tongue, lip and jaw differentiation and its relationship to orofacial myofunctional treatment. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 26: 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul-Brown, D., and R. Clausen. 1999. Collaborative Approach for identifying and treating speech, language, and orofacial myofunctional disorders. Alpha Omegan 92: 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, R. B. 1983. The relationship between mouth breathing and tongue thrusting. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 9: 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, R. B. 1996. Age and articulation characteristics: A survey of patient record on 100 patients referred for tongue thrust therapy. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 22: 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocabado, M. 1987. The importance of soft tissue mechanics in stability and instability of the cervical spine: A functional diagnosis for treatment planning. Cranio 5: 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schievano, D., R. M. P. Rontani, and F. Berzin. 1999. Influence of myofunctional therapy on the perioral muscles. Clinical and electromyographic evaluations. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 26: 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, B., and S. Siersbæk-Nielsen. 1992. Cervical and craniocervical posture as predictors of craniofacial growth. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 101: 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, B., and S. Kreiborg. 1977. Soft-tissue stretching: A possible control factor in craniofacial morphogenesis. Scandinavian Journal of Dental Research 85: 505–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solow, B., and A Sandham. 2002. Cranio-cervical posture: A factor in the development and function of the dentofacial structures. European Journal of Orthodontics 24: 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umberger, F. G., and R. G. Johnston. 1997. The efficacy of oral myofunctional and coarticulation therapy. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 23: 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmann, K. 1960. Über den Zusammenhang der Gebißanomalien mit Krümmung der Wirbelsäule und schlaffer Körperhaltung. Fortschritte der Kieferorthopädie 21: 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, S. D., C. A. Maul, and E. J. Stevens. 1998. The prevalence of orofacial myofunctional disorders among children identified with speech and language disorders in grades kindergarten through six. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 24: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| a: Positive habit history | |||

| Significant (p=0.001) | Significant (p=0.005) | No Correlation | |

| Weak body posture (p=0.000) | Upper cervical spine (p=0.872) | ||

| Iliac spine (p=0.496) | |||

| Open mouth rest posture(p=0.001) | Incompetent lips (p=0.013) | Reclined head position (p=0.174) | |

| Articulation disorders (p=0.000) | |||

| Habits (p=0.000) | |||

| Tongue dysfunction (p=0.000) | |||

| b: Persistent habits | |||

| Significant (p=0.001) | Significant (p=0.005) | No Correlation | |

| Weak body posture (p=0.000) | Iliac spine (p=0.019) | Upper cervical spine (p=0.356) | |

| Articulation disorders (p=0.000) | |||

| Open mouth rest posture (p=0.000) | |||

| Tongue dysfunction (p=0.000) | |||

| Reclined head position (p=0.008) | |||

| Incompetent lips (p=0.007) | |||

| Habit history (p=0.000) | |||

| c: Incompetent lip closure | |||

| Significant (p=0.001) | Significant (p=0.005) | No Correlation | |

| Weak body posture (p=0.000) | Upper cervical spine (p=0.021) | Iliac spine (p=0.628) | |

| Open mouth rest posture (p=0.000) | Tongue dysfunction (p=0.023) | ||

| Articulation disorders (p=0.000) | Habit history (p=0.013) | ||

| Reclined head position (p=0.000) | |||

| Habits (p=0.007) | |||

| d: Mouth rest posture | |||

| Significant (p=0.001) | Significant (p=0.005) | No Correlation | |

| Weak body posture (p=0.000) | Iliac spine (p=0.257) | ||

| Upper cervical spine^p(p=0.772) | |||

| Incompetent lips (p=0.000) | Reclined head position (p=0.029) | ||

| Tongue (p=0.000) | |||

| Habit history (p=0.000) | |||

| Articulation disorders (p=0.000) | |||

| Habits (p=0.000) | |||

| e: Tongue dysfunction | |||

| Significant (p=0.001) | Significant (p=0.005) | No Correlation | |

| Weak body posture (p=0.000) | Iliac spine (p=0.017) | Upper cervical spine (p=0.452) | |

| Reclined head position (p=0.000) | Incompetent lips (p=0.023) | ||

| Habit history (p=0.000) | |||

| Articulation disorders (p=0.000) | |||

| Open mouth rest posture (p=0.000) | |||

| Habits (p=0.000) | |||

| f: Articulation disorders | |||

| Significant (p=0.001) | Significant (p=0.005) | No Correlation | |

| Weak body posture (p=0.000) | Iliac spine (p=0.020) | Upper cervical spine^p(p=0.161) | |

| Habits (p=0.000) | Reclined head position (p=0.011) | ||

| Habit history (p=0.000) | |||

| Tongue dysfunction (p=0.000) | |||

| Mode of breathing (p=0.000) | |||

| Incompetent lips (p=0.000) | |||

| g: Reclined head position | |||

| Significant (p=0.001) | Significant (p=0.005) | No Correlation | |

| Weak body posture (p=0.000) | |||

| Upper cervical spine (p=0.000) | |||

| Iliac spine (p=0.000) | |||

| Habits (p=0.008) | Articulation disorders (p=0.011) | Habit history (p=0.174) | |

| Incompetent lips (p=0.000) | Open mouth rest posture (p=0.029) | ||

| Tongue dysfunction (p=0.000) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2008 by the authors. 2008 Heike Korbmacher, Lutz E. Koch, Bärbel Kahl-Nieke

Share and Cite

Korbmacher, H.; Koch, L.E.; Kahl-Nieke, B. Orofacial Myofunctional Disorders in Children with Asymmetry of the Posture and Locomotion Apparatus. Int. J. Orofac. Myol. Myofunct. Ther. 2005, 31, 26-38. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2005.31.1.3

Korbmacher H, Koch LE, Kahl-Nieke B. Orofacial Myofunctional Disorders in Children with Asymmetry of the Posture and Locomotion Apparatus. International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy. 2005; 31(1):26-38. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2005.31.1.3

Chicago/Turabian StyleKorbmacher, Heike, Lutz E. Koch, and Bärbel Kahl-Nieke. 2005. "Orofacial Myofunctional Disorders in Children with Asymmetry of the Posture and Locomotion Apparatus" International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy 31, no. 1: 26-38. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2005.31.1.3

APA StyleKorbmacher, H., Koch, L. E., & Kahl-Nieke, B. (2005). Orofacial Myofunctional Disorders in Children with Asymmetry of the Posture and Locomotion Apparatus. International Journal of Orofacial Myology and Myofunctional Therapy, 31(1), 26-38. https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2005.31.1.3