Animal Welfare Protocols and Labelling Schemes for Broilers in Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

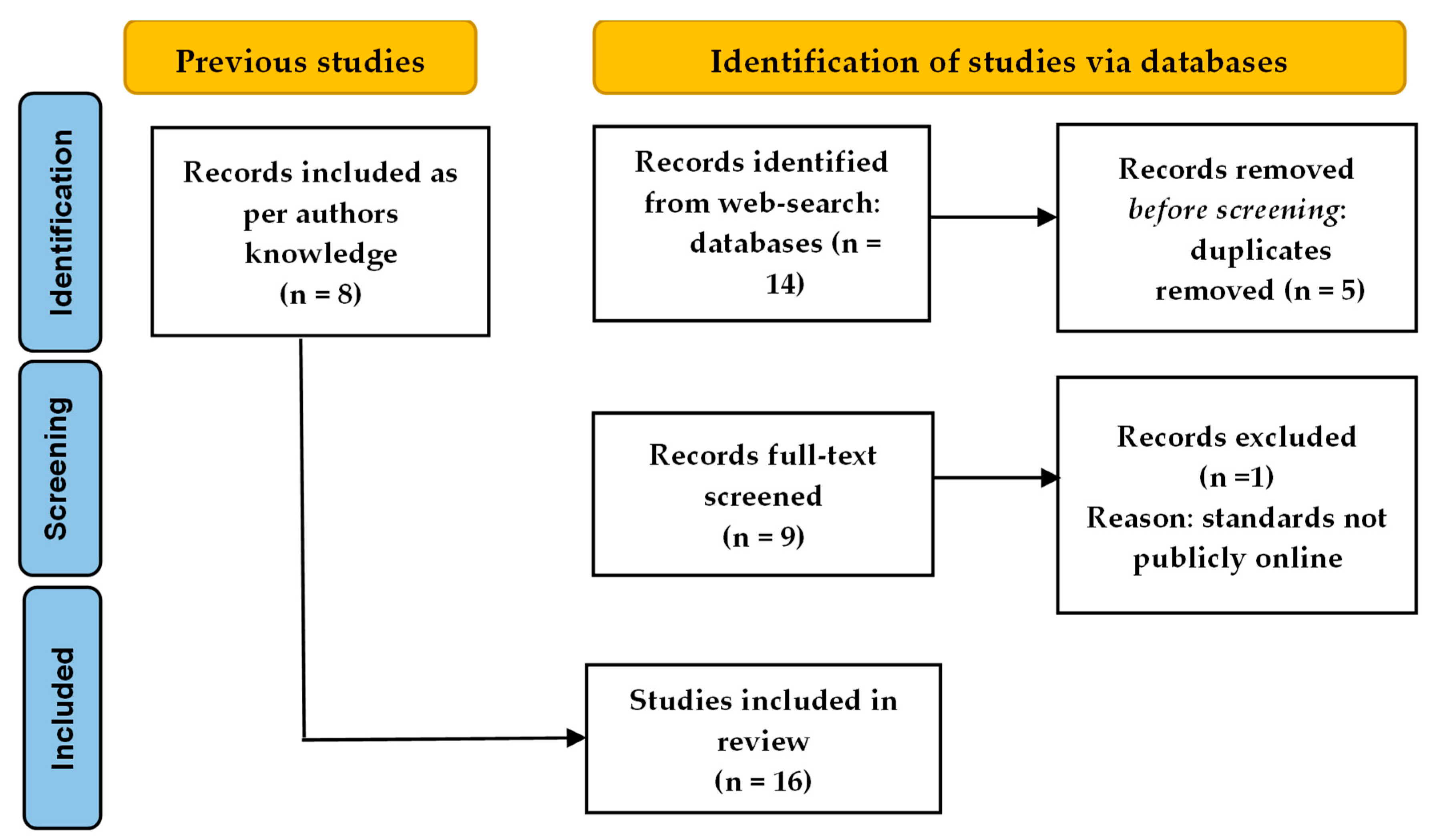

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Committee. Proposed Draft Recommendations on Sustainable Agricultural Development for Food Security and Nutrition Including the Role of Livestock; Article VIII; Animal Health and Welfare: Easton, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Destoumieux-Garzón, D.; Mavingui, P.; Boetsch, G.; Boissier, J.; Darriet, F.; Duboz, P.; Fritsch, C.; Giraudoux, P.; Le Roux, F.; Morand, S.; et al. The one health concept: 10 years old and a long road ahead. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinillos, R.C.; Appleby, M.C.; Manteca, X.; Scott-Park, F.; Smith, C.; Velarde, A. One Welfare—A platform for improving human and animal welfare. Vet. Rec. 2016, 179, 412–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, M.E.; González-Montaña, J.R.; Lomillos, J.M. Consumers’ Concerns and Perceptions of Farm Animal Welfare. Animals 2020, 10, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerkvist, C.J.; Hess, S. A meta-analysis of consumer willingness to pay for farm animal welfare. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2011, 38, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, H.; Pirsich, W.; Theuvsen, L. Criteria-based evaluation of selected european animal welfare labels: Initiatives from the poultry meat sector. AgEcon Search 2014, 14, 174340. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament Ex-Post Evaluation Unit. Animal Welfare on the Farm—Ex-Post Evaluation of the EU Legislation: Prospects For Animal Welfare Labelling at EU Level; Europeam Implementation Assessment; European Parliamentary Research Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT. Meat (Fao.org). Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/09e88a46-b005-4d65-8753-9714506afc38/content (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Animal Welfare; Nielsen, S.S.; Alvarez, J.; Bicout, D.J.; Calistri, P.; Canali, E.; Drewe, J.A.; Garin-Bastuji, B.; Rojas, J.L.G.; Schmidt, C.G.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the welfare of broilers on farm. EFSA J. 2023, 21, 7788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaxton, Y.V.; Christensen, K.D.; Manch, J.A.; Rumley, E.R.; Daugherty, C.; Feinberg, B.; Parker, M.; Siegel, P.; Scanes, C.G. Symposium: Animal welfare challenges for today and tomorrow. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 2198–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinola, K.; Latvala, T.; Niemi, J.K. Consumertrust and willingness to pay for establishing a market-based animal welfare assurance scheme for broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; van Trijp, H.C.M. The impact of broiler production system practices on consumer perceptions of animal welfare. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 3080–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L. Consumer preferences for and beliefs about slow growth chicken. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 4159–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangnat, I.D.M.; Mueller, S.; Kreuzer, M.; Messikommer, R.E.; Siegrist, M.; Visschers, V.H.M. Swiss consumers’ willingness to pay and attitudes regarding dual-purpose poultry and eggs. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brümmer, N.; Christoph-Schulz, I.; Rovers, A.-K. Consumers’ Perspective on Dual-purpose Chickens as Alternative to the Killing of Day-old Chicks. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2018, 9, 390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhonacker, M.; Verbeke, W. Buying higher welfare poultry products? Profiling Flemish consumers who do and do not. Poult. Sci. 2009, 88, 2702–2711. [Google Scholar]

- Naturland. Naturland Standards on Production. Version 5. 2024. Available online: https://www.naturland.de/images/01_naturland/_en/Standards/Naturland-Standards-on-Production.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Global Animal Partnership. Global Animal Partnership 5-Step® Animal Welfare Standards for Chickens Raised for Meat. Version 4.0. Available online: https://globalanimalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/GAP-Standards-for-Chickens-Raised-for-Meat-v4.0.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Animal Welfare Approved by AGW. Certified Animal Welfare Approved by AGW Standards for Meat Chickens. Version 1. 2024. Available online: https://agreenerworld.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/AWA-Meat-Chicken-Standards-2024-v1.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Better Chicken Commitmant. The Policy. Available online: https://betterchickencommitment.com/us/policy/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Biodynamic Federation Demeter. Production, Processing and Labelling. Available online: https://demeter.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/2024_Int_Dem_Bio_Standard_eng.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- A Greener World. Available online: https://agreenerworld.org/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Better Chicken Commitment. Commitments. Available online: https://betterchickencommitment.com/eu/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Global Animal Partnership. Available online: https://globalanimalpartnership.org/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Naturland. Naturland Standards. Available online: https://www.naturland.de/en/producers/service-and-expertise/standards.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Welfare Quality. Welfare Quality Assessment Protocol for Poultry. 2009. Available online: https://www.welfarequalitynetwork.net/media/1293/poultry-protocol-watermark-6-2-2020.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- KRAV. Standards for KRAV—Certified Production—2024/25 Edition. Available online: https://wwwkravse.cdn.triggerfish.cloud/uploads/sites/2/2023/12/krav-standards2024-25-1702048556.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Sigill Kvalitetessystem AB. IP Sigill Kyckling & Ägg Standard för Kvalitetssäkrad Kyckling-Och Äggproduktion. Version 2022:1. 2022. Available online: https://cdn.sanity.io/files/skgc670h/production/75c290a7b4529e9e04cc86a6d90d085c80c6e85a.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- European Commission. Order on the Voluntary Animal Welfare Labelling Scheme. Available online: https://technical-regulation-information-system.ec.europa.eu/en/notification/25529 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Anbefalet af Dyrenes Beskyttelse. Specifikation. Mærkekrav Slagtefjerkræ. Version 16. 2025. Available online: https://www.dyrenesbeskyttelse.dk/sites/dyrenesbeskyttelse.dk/files/AADB/Maerkekrav/2025/maerkekrav-slagtefjerkr%C3%A6-1-januar-2025.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Beter Leven. Broiler Chickens 1 Star. Version 5. 2016. Available online: https://beterleven.dierenbescherming.nl/zakelijk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/07/Broilers-1-star-version-2.1-d.d.-01-09-2016.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Beter Leven. Broilers 3 Stars. Version 2.2. 2023. Available online: https://beterleven.dierenbescherming.nl/zakelijk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/01/Broilers-3-stars-version-2.2-MW-d.d.-02-01-2023.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Biosuisse. Standards for the Production, Processing and Trade of “Bud” Products Effective as of 1 January 2023. Available online: https://international.bio-suisse.ch/dam/jcr:47dc9f0b-3dae-4936-aed8-2f844ab88497/!bio%20suisse%20standards%202023%20-%20en.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Red Tractor Standards Manual. Chickens Standards. Version 5.1. 2025. Available online: https://redtractorassurance.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Chicken-Standards-Feb-2025.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- RSPCA. RSPCA Welfare Standards for Meat Chickens. 2017. Available online: https://science.rspca.org.uk/documents/1494935/9042554/rspca%20welfare%20standards%20for%20meat%20chickens%20(8.48%20mb).pdf/e7f9830d-aa9e-0908-aebd-2b8fbc6262ea?:t=1557668435000 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Conditions De Production Communes Relatives a La Production En Label Rouge. Volailles Fermieres De Chair. 2025. Available online: https://www.inao.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/2025-03/CPC_LR_VolaillesFermieres_v4-2025.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Etiquette Bien-Être Animal. Broilers. Available online: https://www.etiquettebienetreanimal.fr/en/le-poulet/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Animal Welfare. Welfair Certificate. 2024. Available online: https://www.animalwelfair.com/en/bienestar-animal/protocolos-de-evaluacion/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- RSPCA Assured. Available online: https://www.rspcaassured.org.uk/ (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- RSPCA Assured. Meat Chicken Breeds Accepted For Use Within The RSPCA Assured Scheme. Available online: https://business.rspcaassured.org.uk/producer-members/accepted-chicken-breeds/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Papageorgiou, M.; Goliomytis, M.; Tzamaloukas, O.; Miltiadou, D.; Simitzis, P. Positive Welfare Indicators and Their Association with Sustainable Management Systems in Poultry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C.J.; Bouwsema, J.; Caplen, G.; Davies, A.C.; Hockenhull, J.; Lambton, S.L.; Lines, J.A.; Mullan, S.; Weeks, C.A. Farmed Bird Welfare Science Review. 2017. Available online: https://agriculture.vic.gov.au/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Mellor, D.J. Enhancing animal welfare by creating opportunities for positive affective engagement. N. Z. Vet. J. 2015, 63, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RSPCA. Broiler Welfare Assessment Protocol to Determine the Welfare of Broilers. 2017. Available online: https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=34a87e868ae15e4bfa65bd0690e8ae276c3b5df9bfafedd3ae99ea7960cf4465JmltdHM9MTc0Mzk4NDAwMA&ptn=3&ver=2&hsh=4&fclid=31051ba3-dbc4-6aea-3bd2-0ef5dad96bb8&psq=RSPCA+Broiler+Breed+Welfare+Assessment+Protocol&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cucnNwY2Eub3JnLnVrL2RvY3VtZW50cy8xNDk0OTM1LzkwNDI1NTQvUlNQQ0ErQnJvaWxlcitXZWxmYXJlK0Fzc2Vzc21lbnQrUHJvdG9jb2wrTWF5MTcucGRmL2E4ZGZhOGZmLTY5ZWQtZTFhYi1jOTA4LWIxNTIzZTRlYzY0Mj90PTE1NTMxNzEwMzEyODQmZG93bmxvYWQ9dHJ1ZQ&ntb=1&toWww=1&redig=CA49F65982514FCD9B7708101EDF0FF8 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Spitzer, H.B.; Meagher, R.K.; Proudfoot, K.L. The impact of providing hiding spaces to farmed animals: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, M.; Bailie, C.L.; O’Connell, N.E. Evaluation of a dustbathing substrate and straw bales as environmental enrichments in commercial broiler housing. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 200, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, A.C.; Newberry, R.C.; Vas, J.; Mullan, S. Slow-growing broilers are healthier and express more behavioural indicators of positive welfare. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muri, K.; Stubsjøen, S.M.; Vasdal, G.; Moe, R.O.; Granquist, E.G. Associations between qualitative behaviour assessments and measures of leg health, fear and mortality in Norwegian broiler chicken flocks. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 211, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rault, J.-L.; Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Hemsworth, P. The Power of a Positive Human–Animal Relationship for Animal Welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 590867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Pedersen, V.; Tosi, M.-V.; Janczak, A.M.; Visser, E.K.; Jones, R.B. Assessing the human–animal relationship in farmed species: A critical review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 101, 185–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aqil, A.; Zulkifli, I.; Hair Bejo, M.; Sazili, A.Q.; Rajion, M.A.; Somchit, M.N. Changes in heat shock protein 70, blood parameters, and fear-related behavior in broiler chickens as affected by pleasant and unpleasant human contact. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeling, L. Indicators of good welfare. In Encyclopaedia of Animal Behavior, 2nd ed.; Chun, C.J., Ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2019; pp. 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Alvino, G.M.; Archer, G.M.; Mench, J.A. Behavioural time budgets of broiler chickens reared in varying light intensities. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 118, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.M.; Sumpter, D.J.T. The feeding dynamics of broiler chickens. J. R. Soc. Interface 2007, 4, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beter Leven. Poultry Abattoir. Version 3. 2021. Available online: https://beterleven.dierenbescherming.nl/zakelijk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/08/Abattoir-poultry-version-3.0-d.d.-29-07-2021-1.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Animal Welfare Approved by AGW. Animal Welfare Approved Guidelines for Poultry Slaughter Facilities. Version 1. 2024. Available online: https://agreenerworld.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/AWA-Slaughter-Guidelines-for-Poultry-2021-v1.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Red Tractor. Poultry Catching and Transport Standards. Version 4.1. 2017. Available online: https://redtractorassurance.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Poultry-Catching-and-Transport-standards.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Red Tractor. Meat & Poultry Processing Scheme Standards. Version 4.0:1. 2023. Available online: https://redtractorassurance.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/RTStandards_ON-FARM_May23_HR.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Better Chicken Commitment. US Broiler Chicken Welfare. Available online: https://betterchickencommitment.com/us-broiler-chicken-welfare.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Sigill Kvalitetessystem AB. IP Livsmedel Grundcertifiering. Standard för Kvalitetssäkrad Livsmedelshantering. Version 2024:1. 2024. Available online: https://cdn.sanity.io/files/skgc670h/production/0c430212a39101f6206dd5379375062757a47036.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Dawkins, M.; Layton, R. Breeding for better welfare: Genetic goals for broiler chickens and their parents. Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, I.C.; Guémené, D. Major welfare issues in broiler breeders. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2011, 67, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, I.; Gilbert, J.; Liew, P.; Ginsos, J. The effects of regular visual contact with human beings on fear, stress, antibody and growth responses in broiler chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 79, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.P.; Northcutt, J.K.; Steinberg, E.L. Meat quality and sensory attributes of a conventional and a Label Rouge-type broiler strain obtained at retail. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.; Kreuzer, M.; Siegrist, M.; Mannale, K.; Messikommer, R.E.; Gangnat, I.D.M. Carcass and meat quality of dual-purpose chickens (Lohmann Dual, Belgian Malines, Schweizerhuhn) in comparison to broiler and layer chicken types. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 3325–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, P.C.; Ghaziani, S.; Klaiber, I.; Zarate, A.V. Are carcass and meat quality of male dual-purpose chickens competitive compared to slow-growing broilers reared under a welfare-enhanced organic system? Org. Agric. 2018, 8, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerfeldt, M.P.; Gunnarsson, S.; Bernes, G.; Blanco-Penedo, I. Health and welfare in organic livestock production systems—A systematic mapping of current knowledge. Org. Agric. 2021, 11, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C. Health and Welfare in Organic Poultry Production. Acta Vet. Scand. 2002, 43, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sossidou, E.N.; Bosco, A.D.; Castellini, C.; Grashorn, M.A. Effects of pasture management on poultry welfare and meat quality in organic poultry production systems. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2015, 17, 375–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatkamp, H.W.; Luuk, W.; Vissers, S.M.; van Horne, P.L.M.; de Jong, E.C. Transition from Conventional Broiler Meat to Meat from Production Concepts with Higher Animal Welfare: Experiences from The Netherlands. Animals 2019, 9, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Labelling Standards | Tiers (Number) | Origin | Geographical Territory | Initiation | Audit Frequency | Exclusive Focus on Animal Welfare | Type of Husbandry Systems | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KRAV | 1 | Sweden | national (but also in other European countries) | private | annual | no | extensive | [28] |

| Svensk Sigill | 2-IP Sigill Grundcertifiering/klimatcertifiering | Sweden | national | private | annual | no | extensive | [29] |

| Bedre Dyrevelfaerd | 3 | Denmark | national (also Scandinavia, Baltic Area) | public-private | annual | yes | intensive-extensive | [30] |

| Anbefalet af Fyrenrs Beskyttelse | 1 | Denmark | national (also Scandinavia) | private | at least annual (different times over the year) | yes | extensive | [31] |

| Beter Leven | 3 | Nederland | national | public-private | annual | yes | extensive | [32,33] |

| Naturland | 1 | Germany | international (Europe) | private | at least annual | no | extensive | [18] |

| Demeter | 1 | Germany | national (also international) | private | annual | no | extensive | [22] |

| Bio Suisse | 1 | Switzerland | national (also international) | private | annual | no | extensive | [34] |

| Red Tractor Broilers (B)/Enhanced Welfare (EW). Free-range (FR) | 1 | UK | national | private | annual (max 18 months) | no | intensive | [35] |

| RSPCA Assured | 1 | UK (RSPCA) | national (also Ireland, Australia) | private | annual | yes | semi-intensive- extensive | [36] |

| Label Rouge | 1 | France | national | public | at least annual | no | extensive | [37] |

| Étiquette Bien-être animal | 4 (A–D) | France | national | private | annual | yes | intensive-extensive | [38] |

| Bienestar Animal-Welfair (Welfare assessment protocol for broilers) | 1 | Spain | national (also Spain, Portugal) | public (research institutes) | minimum annual | yes | intensive-extensive | [27] |

| Animal Welfare Certified by GAP | 6 (1–5, 5+) | Global GAP | international | private | every 15 months (to cover all seasons) | yes | intensive-extensive | [19] |

| Animal Welfare Approved by AGW | 1 | A Greener World | international | private | minimum annual and in all farms | yes | extensive | [20] |

| Better Chicken Commitment | 1 | Compassion in World Farming | international | private | annual (max 15 months) | yes | intensive | [21] |

| Labelling Standards | Breed | Conversion Period | Beak Trimming Allowed | Stocking Density | Flock Mortality | Light Intensity | Continuous Darkness (Minimum) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KRAV | suitable for organic farming | 10 weeks | no | Indoors: 20 kg/m2, outdoors: 4 m2/bird | Not specified | daylight must be let in via an area equivalent to at least 3% of the floor area | 8 h | [28] |

| Svensk Sigill | all | all life | Not specified | max 20 kg/m2 | Not specified | flicker-free lightning or with of at least 120 Hz flicker frequency | Min 6 h of which min 4 h continuous. | [29] |

| Bedre Dyrevelfaerd | slow growing | No | Not specified | I: 38 kg/m2, II: 32 kg/m2, III: 27.5 kg/m2 indoors, min 1 m2/bird outdoors | max 1% plus 0.06% multiplied by the age of the flock at slaughter in days | Not specified | Not specified | [30] |

| Anbefalet af Fyrenrs Beskyttelse | Slow growing (average gain 38 g/day) | All life | no | Indoors 30 kg/m2, outdoors 1 m2/bird | Not specified | lighting program that ensures a normal circadian rhythm | 8 h | [31] |

| Beter Leven | slow growing | All life | Not specified | I: 12 birds/m2–25 kg/m2, III: 11 broilers/m2 | Not specified | Min 20 lux, daylight-permeable surface min 3% of the ground surface | 8 h | [32,33] |

| Naturland | suitable for organic farming | 10 weeks; small poultry 6 weeks | no | Pasture: 480 birds per hectare, indoors: max 21 kg live weight/m2, outdoors: 4 broilers/m2 | Not specified | Natural ligh, not specified | 8 h | [18] |

| Demeter | all | All life (half if organic) | no | 1 m2/kg live weight | Not specified | Not specified | 8 h | [22] |

| Bio Suisse | dual-purpose chickens, parent chicks may be of non-organic provenance. | 56 days for poultry entered before 3 days of age | no | 15 pullets/m2 1–42 days, 8 birds/m2 > 42 days | Not specified | Natural light | 8 h | [34] |

| Red Tractor Broilers (B)/Enhanced Welfare (EW). Free-range (FR) | B, FR, EW: Hubbard: JA757, JA787, JA957, JA987, Redbro (indoor use only), Norfolk Black, JACY57-Aviagen: Rambler Ranger, Ranger Classic, Ranger Gold | B, FR, EW: no | B, FR, EW: no | B: Max 38 kg/m2, EW: 30 kg/m2, FR: 27.5 kg/m2 | B, FR, EW: Max 5% | B, FR: 20 lux measured at bird eye level and recorded once every crop illuminating at least 80% of the usable bird area, during lighting periods, EW: Lighting intensity min 50 lux-natural daylight through windows (min of 3% of the floor area) | B, EW: Min 6 h of which min 4 h continuous, FR: min 6 h | [35] |

| RSPCA Assured | Hubbard: JA747, JA957, Norfolk Black, JACY57– Aviagen: Ranger Gold, Rambler Ranger (indoor and free-range) (JA787, JA987, Redbro, Ranger Classic, Rustic Gold: under derogation) [41] | All life | no | Indoors: 19 birds/m2–30 kg/m2, free-range: 13 birds/m2–27 kg/m2 | Not specified | Natural light no later than 7 days of age, prior min 20 lux, min 8 h continuous light/day | min 6 h and max 12 h continuous darkness, | [36] |

| Label Rouge | slow-growing specific breeds (separate section) | All life | Not mentioned | Indoors: 20 birds/m2 (40 kg/m2), outdoors: 2 m2/bird | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | [37] |

| Étiquette Bien-être animal | all | All life | Not mentioned | D: max 38 kg/m2, C: 30 kg/m2, B:27.5 kg/m2, A: 25 kg/m2, outdoors A 1 m2/bird, B 2 m2/bird | Not specified | Permeable area of natural light 3% of surface A, B, C, less D | 6 h A, B, C and 4 h D | [38] |

| Bienestar Animal -Welfair (Welfare assessment protocol for broilers) | slow growing | Not specified | Yes (beak trimming criterion) | Not specified | Not specified but on farm mortality criterion | Not specified | Not specified | [27] |

| Animal Welfare Certified by GAP | all tiers 1–3, slow growing 4–5+ (From 1 June 2030, breeds that are able to perch throughout their lives for all tiers) | All life | no | 6 lbs/ft2 (29 kg/m2) tiers 1–3, 5.5 lbs/ft2 (27 kg/m2) tiers 4–5+ | 6% tier 1, 5% tiers 2, 3, 4% 4–5+ | Light intensity in housing 50 lux during over 80% of the floor space is used by the birds | 6 h tiers 1, 2, 8 h tiers 3, 4 by 3 days of age, 8 h tiers, 5, 5+ from start | [19] |

| Animal Welfare Approved by AGW | recommended traditional breed and dual-purpose breeds | All life, or placed max at 36 h age | no | Indoors: 0.06 sq meters/bird and extra 0.18 sq meters/bird when excluded from foraging | Not specified | Min 20 lux | 8 h | [20] |

| Better Chicken Commitment | breeds that demonstrate high welfare outcome (slow growing)-also approved by RSPCA | All life | no | Max 30 kg/m2 | Not specified | Min 50 lux | 6 h continuous | [21] |

| Labelling Standards | Perches | Access to Pasture/Outdoors | Vegetation/Foraging Materials | Specific Other Environmental Enrichment | Positive Welfare Indicators | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KRAV | At least 5 cm or at 25 cm2 raised sitting area or all combinations of these | As much as possible, min 4 months, 12 h/day | adequate number of trees, bushes etch where birds can seek shelter and security | sand baths in a number so that all birds can use them freely both indoors and on the perches and raised seats indoors | Exploration, behavioral synchronization, comfort, areas of seclusion, perching | [28] |

| Svensk Sigill | min 150 mm/bird | Free access outdoors (veranda or conservatory) | Not specified | min 1 bale straw/hay per 100 m2, each weighing at least 10 kg, elevated platforms with a surface area of min 0.36 m2 per 100 m2 and min height 20 cm, placed when birds 7–12 days age | Exploration, behavioral synchronization, comfort, perching, play | [29] |

| Bedre Dyrevelfaerd | not specified | I:no, II: yes and at last 12 days of life all day | II: outdoors space min 15% indoors, III: min 25% covered with vegetation, min 18% planted with shrubs and/or trees, min 7% ground cover | II, III: roughage and enrichment in general | II, III: exploration, perching, seclusion areas, behavioral synchronization | [30] |

| Anbefalet af Fyrenrs Beskyttelse | At least 5 cm or at 25 cm2 raised sitting area or all combinations of these | Since birds are fully feathered, but no later than 6–7 weeks of age in the summer period and no later than 9 weeks of age in the winter period (1 October–15 April) | Grass and vegetation for protection and shelter (straw bales and windbreaks if needed) | raised platforms (resting areas) and/or straw bales since birds are 2 weeks old. | Exploration, behavioral synchronization, comfort, areas of seclusion, perching, play | [31] |

| Beter Leven | Not specified | The broilers have access to the covered run from the age of 21 days, min 8 h/day | covered run has an area of min 20% of the total area of the barn. | From 15 days age, min 2 g of grain/feed per broiler per day is provided as enrichment material, from 8 days age, a min 1 straw, hay, or lucerne bale of 15–20 kg per 1000 broilers is provided in the barn/Usable floor surface area covered entirely by loose, white wood chippings, wood shavings, loose straw, loose chopped straw | Exploration, behavioral synchronization, comfort, areas of seclusion, play | [32,33] |

| Naturland | 5 or 25 cm2 raised sitting level/bird | Always outdoor access, foraging when weather allows (veranda obligatory, conservatory if more than 200 poultry) | trees, bushes, suitable outdoors | Sand- and dustbath in conservatory, appropriate litter over at least 33% of the base run | Exploration, foraging, behavioral synchronization, comfort, areas of seclusion, perching | [18] |

| Demeter | elevated resting places must be provided | Yes, pasture/veranda | min 40% of the area evenly covered with perennial crops to provide protection, e.g., bushes and trees. | Sandbathes mandatory | Exploration, comfort, areas of seclusion, behavioral synchronization | [22] |

| Bio Suisse | 8 cm/bird 1–42 days. 14 cm/bird > 42 days | Yes, outdoors no later than 43 days of age, Cockerels and dual-purpose chickens access to pasture min 50% of their life, structure must offer min 2 m2 shade | structural elements e.g., bushes, trees, protective netting and shelters that provide shade and protection | Dustbath 150 birds/m2 and at least 5 cm depth when birds > 42 days/appropriate bedding | Exploration, comfort, areas of seclusion, behavioral synchronization, play | [34] |

| Red Tractor Broilers (B)/Enhanced Welfare (EW). Free-range (FR) | B, FR, EW: Min 2 linear m perch or 0.3 m2/1000 birds. B: Max 15 cm off the ground, FR, EW: max 10 cm off the ground | B, FR: access to the range for at least half their lives, min 8 h/day | B, FR, EW: Not applicable | B, FR, EW: clean, fresh bedding with min depth 2 cm, min 1 bale/1000 birds by day 3, min 1 pecking object/1000 birds | B, FR, EW: Exploration, comfort, perching, play | [35] |

| RSPCA Assured | 2 m perch/1000 birds | access to the range min half their lifetime and, no later than 28 days of age for free-range labelling, no later than 35 days of age to be labelled organic | mainly covered by living vegetation, shade and shelter min 8 m2/1000 birds | litter average min depth 5 cm and must allow birds to dustbath, wood shavings the perfect, 1.5 standard sized, long chopped straw bales and one pecking object/1000 birds | Exploration, comfort, areas of seclusion, behavioral synchronization, play, perching | [36] |

| Label Rouge | Not specified | Access to pasture max at 6 weeks of age | Covered mostly with vegetation e.g., trees. hedges, groves, min 20 trees or shrubs | Dry, soft litter to ensure comfort | Exploration, comfort, areas of seclusion, behavioral synchronization | [37] |

| Étiquette Bien-être animal | Yes, not specified, in all tiers | Access outdoors A, B: min half-life 8 h/day | High vegetation in A, not specified | Pecking objects in all tiers | Exploration, perching, play | [38] |

| Bienestar Animal -Welfair(Welfare assessment protocol for broilers) | Not specified | Not mandatory, for free range/extensive systems free range criterion: proportion of birds using the range | Cover on the range criterion: vegetation which the birds can use for cover or manmade shelters | Plumage cleanness, litter quality criteria | Exploration, comfort, behavioral synchronization, play, positive emotions (QBA), human-animal relationship (avoidance test in farms, Flapping on the line in slaughterhouses) | [27] |

| Animal Welfare Certified by GAP | Starting 1/6/2030-perches must be provided min 80 in (200 cm)/1000 birds tiers 1, 2, starting 1/6/2027 tier 3, 1/6/2025 tiers, 4, 5, already tier 5+ | Tiers 1, 2: access outdoors not required, tier 3: min 2 weeks by 28 days age, tiers 4–5+ from 28 days everyday access outdoors | Pasture raised labelling requires not less than 51% rooted vegetative cover, up to 75% covered at tier 5+, occupied outdoor areas must contain features that encourage foraging | All: litter of quality/quantity to provide comfort and allow for dust-bathing and foraging/scratching, min 7.5 cm, tier 1: 1 enrichment/1000 birds, tiers 2–4, 2 different enrichments/1000 birds | Exploration, comfort, behavioral synchronization, play, perching, seclusion areas | [19] |

| Animal Welfare Approved by AGW | Access to elevated areas from 4 weeks of age, 1 inch/bird perch or 1 inch2/bird straw bale (min 5, 5 inches height) | Access to forage by 7 days of age but recommended by 24 h age, min 50% of daytime | access to growing green vegetation | All must have access to dustbaths | Exploration, comfort, behavioral synchronization, play, perching, seclusion areas | [20] |

| Better Chicken Commitment | 2 m/1000 birds | Developed also for intensive systems | Not specified | 2 pecking substrates/bird | Exploration, comfort, perching | [21] |

| Labelling Standard | Separate Section | Maximum Transport Time | Maximum Stocking Density in Delivery Box | Stunning Methods | Minimum Slaughter Age (days) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport | Slaughter | ||||||

| KRAV | no | No | Best minimum, not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 81 no slow, 10 weeks slow growing | [28] |

| Svensk Sigill | yes | Yes | 8 h | weight < 1.6 kg 180–200 cm2/kg, 1.6 to < 3 kg 160 cm2/kg, 3 till < 5 115 cm2/kg, >5 kg 105 cm2/kg | blow to the head, electricity, carbon dioxide | Not specified | [58] |

| Bedre Dyrevelfaerd | no | No | 6 h | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | [30] |

| Anbefalet af Fyrenrs Beskyttelse | yes | Yes | 8 h | Not specified | Gas stunning | Not specified | [31] |

| Beter Leven | yes | Yes (separate standard) | 4 h | Not specified | Controlled Atmosphere Stunning | I: 56, III: 81 days | [56] |

| Naturland | yes | No | 8 h | Not specified | Not specified | 81 | [18] |

| Demeter | no | No | Minimized, on farm slaughter recommended | Not specified | Not specified | 81 | [22] |

| Bio Suisse | no | No | 8 h | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | [34] |

| Red Tractor Broilers (B)/Enhanced Welfare (EW). Free-range (FR) | Yes (separate standard) | Yes (separate standard) | 8 h | poultry > 1.6 kg: 180–200 cm2/kg–1.6 kg–3 kg: 160 cm2/kg, 3 kg–5 kg–115 cm2/kg | controlled atmosphere stunning using inert gas or multi-phase systems, electrical stunning only permitted without live inversion | Not specified | [58,59] |

| RSPCA Assured | yes | Yes | 4 h | 57 kg of birds/m2 of tray floor area | Controlled atmosphere stunning and electrical stunning allowed, but the second not recommended | Not specified | [36] |

| Label Rouge | no | Yes | 3 h | Not specified | Not specified | 81 days | [37] |

| Étiquette Bien-être animal | yes | Yes | 4 tier A, 6 tier B, 8 tiers C, D, E | Not specified (but mortality specified) | Controlled atmosphere stunning and electrical stunning allowed | 81 days A, 56 days B, C, D not specified | [38] |

| Bienestar Animal -Welfair (Welfare assessment protocol for broilers) | no | No | Not mentioned | Not specified but stocking density in crates criterion | Not specified | Not specified | [27] |

| Animal Welfare Certified by GAP | yes | yes | 6 h (tier 5+ on-farm slaughter) | Max 4 in2 (26 cm2) | controlled atmospheric stunning using inert gas or multi-phase systems | Not specified | [19] |

| Animal Welfare Approved by AGW | yes | Yes (separate standard) | 4 h | Max 7 lbs (3 kg) per cubic foot (0.028 cubic meters) in crates | Penetrating /non-penetrating captive bolt, electric stunning via handheld devices/dry plate, controlled atmosphere stunning, controlled atmosphere killing | Not specified | [57] |

| Better Chicken Commitment | yes | yes | 8 h | Not specified | atmospheric stunning using inert gas or multi-phase systems, or electrical stunning without live inversion | Not specified | [21] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papageorgiou, M.; Tzamaloukas, O.; Simitzis, P. Animal Welfare Protocols and Labelling Schemes for Broilers in Europe. Poultry 2025, 4, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry4030029

Papageorgiou M, Tzamaloukas O, Simitzis P. Animal Welfare Protocols and Labelling Schemes for Broilers in Europe. Poultry. 2025; 4(3):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry4030029

Chicago/Turabian StylePapageorgiou, Maria, Ouranios Tzamaloukas, and Panagiotis Simitzis. 2025. "Animal Welfare Protocols and Labelling Schemes for Broilers in Europe" Poultry 4, no. 3: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry4030029

APA StylePapageorgiou, M., Tzamaloukas, O., & Simitzis, P. (2025). Animal Welfare Protocols and Labelling Schemes for Broilers in Europe. Poultry, 4(3), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/poultry4030029