Abstract

The Hook model is used in digital products to engage and retain users through the mechanism of habit formation. This paper explores the use of Hook model techniques in two mobile applications, one being a popular taxi service (Uber taxi) and the other a social network (Instagram). The goal of this paper is to explore the Hook cycle patterns in the two products, and to identify commonalities and differences in how they are applied. Our results suggest that Hook cycle patterns appear with similar frequency; however, Instagram includes more internal Trigger calls. Uber uses fewer triggers to encourage usage, most probably because users already have a specific need for the application. For the same reason, Uber has less opportunity to fail in the reward delivery, while Instagram can use the failure (in providing a reward) as another trigger if the usage habit is already established. In addition, we introduce two types of Hook cycle patterns: internal (within a single use case) and external (transition between use cases). The insights obtained through the case studies serve as a practical reference for developing engaging and retention-focused applications.

1. Introduction

For many software products, user retention and engagement are the primary metrics of product success [], as they allow for growth and in the ideal case can result in conversion to sales. One way to increase engagement and retention is to habituate the user to the product. The Hook model, authored by Nir Eyal in 2013 [], suggests a set of techniques for habit formation in digital products. The main idea behind it is to make users go through a set of interactions with the product, called the Hook cycle, starting from the Trigger, followed by Action and Reward, into the final step called Investment. After going through the cycle a number of times, the user is expected to create an association that the product is the solution for a certain type of problem or discomfort.

In this paper, we examine the use of Hook model techniques in two applications with varying business models. One is a taxi-ordering application (Uber taxi) that aims to satisfy the customer through an easy and quick service. The other is a social network (Instagram), which mainly earns from advertising, and thus the more time users spend on the app, the better.

Our hypothesis is that the ‘use patterns’ of the Hook model will vary depending on a product’s context. Thus, we investigate both the difference and similarities in the Hook model patterns for the two case study applications. Our particular focus is on examining the applications’ features and deconstructing their use cases. The objective is to analyze how the Hook model’s four stages are implemented in these use cases and to identify any patterns unique to each application. The comparative analysis of the two case studies helps us identify the patterns of the application of the model for the two products, highlight the similarities and differences, and arrive at a qualitative description of the necessary conditions and the mechanism of how the Hook model is implemented in practice.

1.1. Background

Many products rely on users forming the habit of using the product []. The Hook model attempts to describe and instruct on how the habituation can be incorporated via the product design process. The process is called habit-testing [] and promotes a user-centered and iterative approach [].

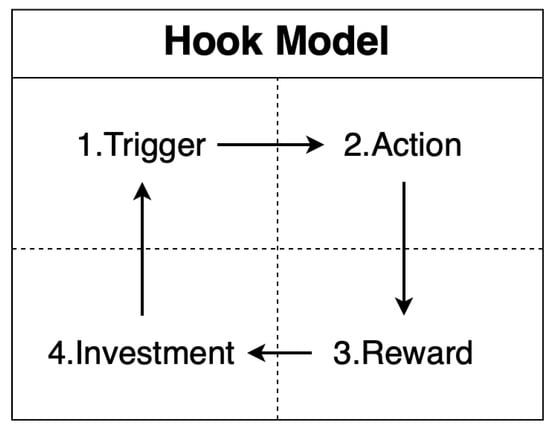

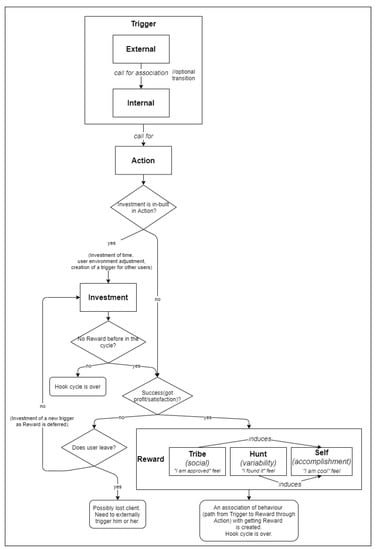

As shown in the Figure 1, the model is a four-step looped process that consists of a Trigger that actuates a certain user behavior, an Action that the user takes regarding the product, a Reward that the user receives in response to their Action, and an Investment that should encourage future use of the product. It is the last step that distinguishes the Hook model from the traditional habit-creation loop [], and this is also the key feature that uses the leverage that digital products have. Investing some effort, social capital, data, money, or time adapts the product to user demand and creates an effect of ownership. Hence, the next time the user wishes to keep the “progress” or Investments, they react to the Trigger, which is not necessarily an external one, and return to the application to obtain their Reward again. Table 1 and the following paragraphs examine the four Hook model stages in more detail.

Figure 1.

Hook model cycle: how digital products form habits.

Table 1.

Description of Hook cycle stages.

The first stage is the Trigger: initially, it can be in the form of an external Trigger, for example, a notification, email, advertisement banner, or sound. The key idea is that it should bring the user to the product, and in a way is similar to the conditioning [] used in associative learning—the famous Pavlovian conditioning []. In digital products [,], the most commonly used external Triggers are carried out via affecting the vision and hearing. External Triggers should be well-timed, actionable, and intriguing to work on a user [].

After several repetitions of the habit-forming cycle, external Triggers should transform into internal Triggers in the form of a desire (coming from within) to use the product. The process of formation of individual Triggers is distinct for each person and is based on the user’s affordances, past experience, culture, and other similar aspects [,]. However, there are still common reactions (to a huge extent) for people of similar demographic groups, so, while creating Triggers and user interaction scenarios, the application designer refers to the target audience’s affordances. An example of an internal Trigger can be a person seeing a beautiful landscape and then proceeding to take a photo of it and post it on social networks. In this case, the external Trigger is not needed anymore—the Action is performed in the presence of the unconditioned stimulus Trigger because the link “sensor condition–Action” is built.

The second and third stages of the Hook cycle are the Action and Reward. Prompted by a Trigger, the Action depends on the user’s motivation and ability [,]; therefore, generally a product must simplify the Action and make it as intuitive as possible. Intuitiveness in design is highly encouraged as it creates a desirable user experience []. The Reward should follow as a response to the Action. Interestingly, the joy of receiving a Reward is higher when there is an uncertainty of obtaining a Reward, i.e., when the Reward is variable []. It also could be explained that physiologically the joy is connected with the anticipation of the Reward, not the receipt itself [,]. Thus, the Hook model considers the anticipation of the Reward to be one of the key factors for users to be habituated to product use. Moreover, the Action–Reward sequence helps to create the internal Triggers associated with receiving a Reward in the form of the product value.

Eyal [] mentions three types of Rewards: tribe, hunt, or self. The Reward of tribe means social acceptance, feeling joy from communication; the Reward of hunt means satisfaction from obtaining the result after searching and exerting effort; the Reward of self is connected to the feeling of self-excellence and self-significance. Social acceptance and achievements definitely play in favor of self-esteem []; therefore, the Rewards of tribe and hunt affirm and provoke receiving a Reward of self. In addition, the Reward of the hunt is close to the Reward of self, since both are about achieving a result—therefore, the hormone of joy, serotonin, is produced similarly. From the use cases, you can see that if the Reward includes a tribe, then it is also either a hunt or a self. If it does not include a tribe, it is still either hunt or self; therefore it all boils down to the Reward of self, a confirmation of self-worth.

The fourth stage in the Hook model is the Investment []. This stage is aimed to increase the value for users stored in the application. Another significant point here is that people prefer to keep the habit if there are efforts and sources that have already been invested in it. A user is not likely to move from one product to another with similar functionality as the first application already contains groups of people, history, and attachments. Therefore, this effect can either (or both) help keep users with the application or contrarily create a competitive strength that allows a user to transfer from a similar service to a new one with enough motivation. The Hook model is a type of persuasive technology. However, Hook focuses on creating a habit of application usage and aims to change behavior in this way, thus increasing the engagement, retention, and stickiness metrics numbers. Table 1 states the definitions of each Hook stage. The attribution of each use case to one of the stages is determined according to the specified definitions.

Importantly, the Hook model aims to engage the user within the application as much as possible. However, the ethical aspect of such application-creation techniques should be questioned. Several advisory models attempt to define the ethics of habit-forming products []; however, reviewing them is outside the scope of this study. According to Verbeek [], persuasive technology is a tool set that creates a specific relation of the user to reality, and there are two directions in which it can act: either shape the human attitude to the reality by managing the interpretation and perception of the human, or change the behavior of the user in reality, managing human Actions. Their technology can be considered as a mediator between human and reality. For a product team, these effects have to be measured through metrics based on the business goals [] and customer objectives [] and ideally directly tied to delivering customer value [].

1.2. Related Work

The Hook model can be used in various contexts. Filippou et al. [] apply the Hook model in combination with the behavior model in an educational app to help students build habits. That study emphasizes that to effectively apply the model, the designers should aim to reinforce specific behaviors. It would therefore be of interest to try concluding which behaviors are targeted with the two case study applications. Razi and Putra [] combine the model with communication strategies in the context of a “Lost and Found” service and explores various types of rewards in a social setting. De Troyer et al. [] use elements of Hook model in combination with the behavior model to counter school burnout phenomena in students and argue that a personalized approach should be taken in regards to applying the techniques.

Researchers also explore ways to expand the model, to make it more practical, and to counter its effects. Liu and Li [] map the Hook model stages to axiomatic design theory (ADT) in an attempt to augment the model and provide a process of how habit formation can be designed from the point of view of ADT. However, they do not validate their suggested approach. Ertemel and Aydin [] argue that the Hook model can be used to architect addiction and that to mitigate its effects individuals can act in the manner opposite to what the model suggests. Lastly, Yao [] explores the use of the model within the popular WeChat application and concludes that one of the key aspects of the model is the necessity to iterate through the habit cycle as often as possible and that Investment plays a key role in increasing the probability of a new cycle.

However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no research comparing how the use of the Hook model can vary depending on the context of the product. Thus, the aim of this study is to fill the gap by identifying patterns of the application of the model for two different products, one being a popular taxi-ordering service (Uber (https://www.uber.com/, accessed on 26 April 2023)) and another a social media application (Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/, accessed on 26 April 2023)). The authors compare the use of Hook model techniques between the two applications and attempt a detailed qualitative description of the necessary conditions and the mechanism of how the user moves along the Hook cycle. The following section describes the methodology of data collection and the respective comparisons of the two products.

2. Methodology

2.1. Application Selection Criteria

We identify and explore the patterns of the Hook model in the two chosen applications, Instagram and Uber taxi. The rationale for selecting these applications is based on three aspects stated below:

2.1.1. Popularity

Nir Eyal (https://www.nirandfar.com/, accessed on 26 April 2023)) defined the Hook model as the result of exploring different examples of successful, worldwide popular applications that took a leader position and had high numbers in terms of daily active users, revenue, the total number of users, and other metrics. For our inquiry, it is also important to choose applications of similar popularity.

2.1.2. Platform

According to gs.statcounter.com (accessed on 26 April 2023) [], the share of mobile devices in the international market is 14% higher than the share of desktop devices. Furthermore, mobile devices are always at hand. According to Fogg’s behavioral model (https://behaviormodel.org/, accessed on 26 April 2023), this increases the possibility of an Action happening. Statistics [] also shows that the market share of Android is around 75% and iOS, about 25%. We, therefore, decided to take Android into consideration.

- 1.

- Instagram []:

- (a)

- total number of users = 1 billion (2020);

- (b)

- daily active users = 500 million (Instagram Stories) (2020);

- (c)

- revenue = USD20 billion (ads) (2019).

- 2.

- Uber []:

- (a)

- total number of users = 93 million (2020);

- (b)

- daily active users = 18.7 million (2020);

- (c)

- revenue = USD11.14 billion (2020).

2.2. Pattern-Search Process

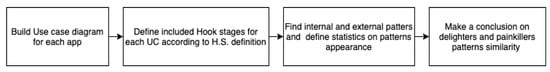

The process of pattern-search methodology is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Process of pattern-search method.

- 1.

- For each product, we build a use-case diagram.

- 2.

- Further, we examine each use case for the presence of Hook cycle stages. The Trigger for starting the use case, Investments, and Rewards obtained by the user are defined according to the Hook model stages definition.

- 3.

- We calculate the statistics of repetitions of the Hook cycle stage patterns in these use cases (internal patterns). Hence, we determine the percentage of patterns that are met in the use-case diagram for each of the case studies.

- 4.

- Then we look at the transitions between use cases, which are triggered by external patterns. The external pattern is a transition from a use case to the next one. The last Hook stage in the first use case and the first Hook stage in the second are taken as the beginning and end of an external transition, respectively.

The data for the sections of the features was manually researched through application functionality manual investigation and written down in the form of use cases. The connections/transitions from one feature to another were depicted in the use-case diagram in the form of association, extend, and include relations.

Hence, we know the proportions of transitions between the Hook stages inside the use cases, those inside the Hook cycle, and between different Hook cycles. Statistical data enable a comparison of how the Hook model is represented in both case studies; we qualitatively explain such differences.

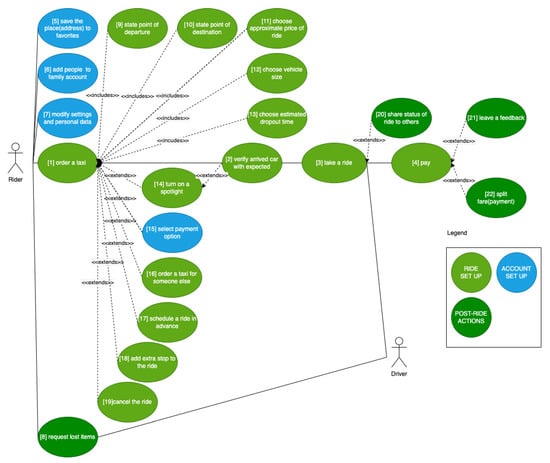

3. Results

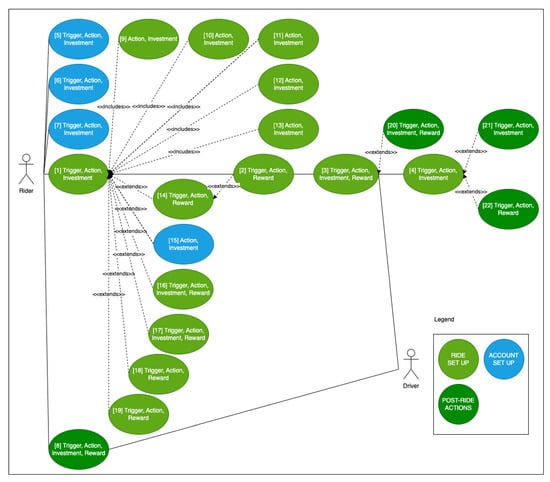

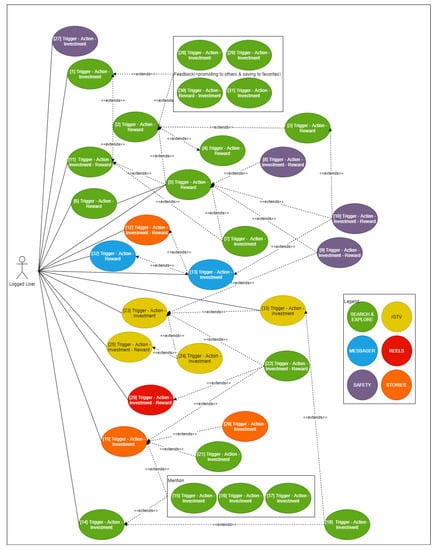

In this study, we searched for two types of patterns: internal (a combination of the Trigger, Action, Investment, and Reward stages within one use case) and external (transition between two use cases). To find the patterns, we have outlined most of the existing functionality of Instagram and Uber taxi through the use-case diagrams (see Appendix A). The use cases include most of the features and scenarios available in March 2021. Figure A2 and Figure A4 in Appendix A provide mapping visualization by presenting each use case in the diagram as a combination of Hook stages.

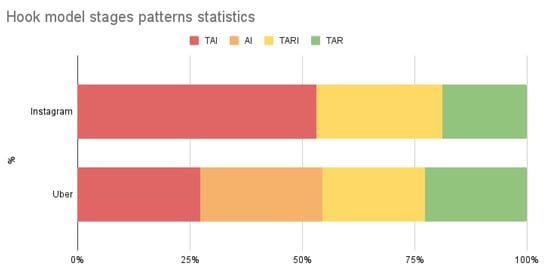

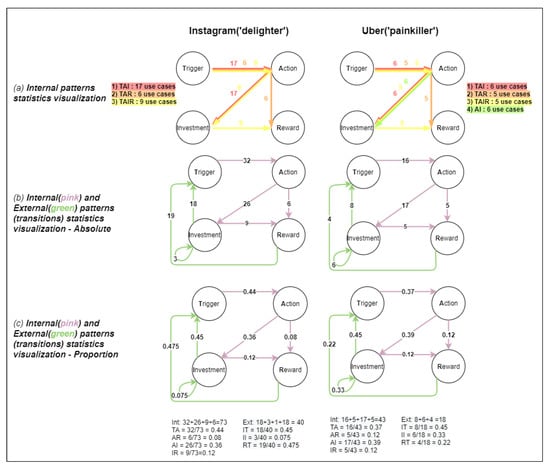

The graph in Figure 3 shows the internal pattern statistics visualization based on the list of use cases presented in the diagrams. Table 2 counts the number of repetitions of each pattern (TAI, TAR, TAIR, AI) in the features (each use case). The figures show the patterns of transitions from one pattern component (Trigger, Action, Reward, Investment) to another, for example, the TAI pattern—transitions from Trigger to Action and to Investment sequentially within one case.

Figure 3.

Internal patterns of Hook model stages within use case for Instagram and Uber.

Table 2.

Number of occurrences of Hook stage patterns within the two products, and ration to all use cases.

The next block (b) shows the internal and external patterns. The pink color shows the number of transitions between components in the original patterns. The pink numbers of transitions between components correspond to the sum of transitions between the components in different patterns, e.g., Trigger–Action = 32 = 17(TAI) + 6 (TAR) + 9 (TAIR).

Green represents the external transitions between the patterns from the case diagram (the link between the last component of one case and the first component of the next case). For example, if the first case is represented by the TAI pattern and the next case is represented by TARI, then the “external transition” is an Investment–Trigger (the last component of the first case is the first component of the second one). Block (c) shows the proportion of each transition between pattern components to the total number of transitions, separately for external and internal transitions.

3.1. Internal Patterns

To identify an internal pattern, a separate use case is taken, and then its stages are recorded as a pattern. Statistics on them are provided in Table 2. We visualize them in Figure 3 (percent—from the number of all use cases for each of the products).

TAI, AI, TARI, and TAR are abbreviations of Trigger–Action–Investment, Action–Investment, Trigger–Action–Reward–Investment, and Trigger–Action–Reward, respectively.

Table 2 is generated from the use cases that are presented in the use-case diagram.

The following observations are made:

- 1.

- The percentage of patterns Trigger–Action–Reward and Trigger–Action–Reward–Investment for both services are equal and are numerically about 23%. However, for Instagram, the TARI pattern is more common (28%).We can conclude that on Instagram, the use cases are more complete, i.e., they include all stages of the Hook cycle and often combine both Reward and Investment at the same time. This means that the use case includes a full Hook cycle. This brings us to the conclusion that Instagram use cases are designed so that the user could become used to going through each use case separately. The goal is for them to become accustomed to utilizing at least a portion of the application, if not the entire application.Note that the percentage of use cases with a Reward is the same for both products.

- 2.

- The patterns Trigger–Action–Investment and Action–Investment together represent about 53–54% for each product. However, the percentage of these patterns for each product varies greatly: TAI on Instagram—53%, on Uber—27%; AI on Instagram—0%, on Uber—27%.Recall that the Trigger that is taken into account if the context is internal (the desire or need to do something), and not external, since any clickable element can become an external Trigger during application use [].A possible explanation is that in Uber, when receiving a specific service, the user goes through a certain scenario (a chain of use cases) because it is necessary to receive the service (tunneling in persuasive technology). On Instagram, the user is free to do whatever they want, because their goal is not to complete a certain sequence of Actions to receive a service.

- 3.

- No certain pattern of Investment and Reward alteration was retrieved. By initial assumption, a Reward is assigned to the use case if there is a chance to obtain it, not a certainty. A user could repeat the use case, and thus Hook cycle several times before they reach the Reward (for example, open several recommended pages until finding some suitable). Therefore, it might be useful to check for users’ behavioral patterns of how persistent they are when trying to obtain a Reward and conduct a UX experiment, but this is beyond this case study.

- 4.

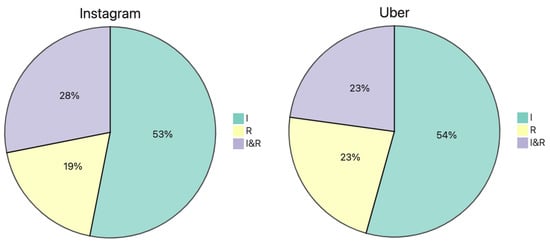

- The Investment stage is more common than the Reward stage, according to statistics for the studied use cases, by 1.7 times (this is true for both products.)The graph in Figure 4 shows the proportions of use cases containing Reward, Investment, or both stages at once.

Figure 4. The number of use cases (UCs) containing Investment to the number of UCs containing Reward relates by 1.7.This is important, because the Action stage is present in every use case, just as the Trigger stage, is with the exception of Actions that are performed by the user because they want to finish the Action to obtain the result; therefore they perform the Actions without extra Triggers.

Figure 4. The number of use cases (UCs) containing Investment to the number of UCs containing Reward relates by 1.7.This is important, because the Action stage is present in every use case, just as the Trigger stage, is with the exception of Actions that are performed by the user because they want to finish the Action to obtain the result; therefore they perform the Actions without extra Triggers.

3.2. External Patterns

To identify the external pattern, the connection between the transition between the two use cases is taken. The last stage of the Hook cycle, presented in the first use case, and the first, presented in the second use case, are considered as a start and finish point, respectively.

The following observations are made:

- 1.

- The transition from Investment to Trigger is similarly popular in both products—around 46%.According to the Hook model this is the classical transition, and thus most expected to be met.

- 2.

- Investment–Investment is not so common. For Instagram, its share is only 7.5%, because, despite the large number of use cases that include Investment (for Instagram and Uber, the proportion of those including Investment stages from all presented is approximately equal—graph in Figure 4). Most of the use cases there begin with an internal Trigger.Moreover, because the Instagram user does not have a “global goal” to obtain some specific benefit/service, they are constantly involved in the use of the application by provoking internal Triggers.In Uber, many use cases start without the participation of an internal Trigger (about 31%), since the use cases are a logical continuation of each other—stages to achieve the goal and obtain the main Reward—so for Uber the percentage of such I–I patterns is much higher—35%.

- 3.

- The pattern Reward–Trigger in Instagram occurs as often as I–T—in 47.5% of cases. In Uber, this pattern is not popular—only 18%. Recall that the ratio of use cases with Investment to use cases with Reward is the same for both products. Therefore, such a difference in the presence of a pattern in the products can be explained by the fact that there are more variations in Instagram for the transition from a use case—greater graph connectivity. In Uber, there is the main scenario and several side ones, plus for many Reward is the final state of the use-case chain. Therefore, there are also fewer transitions from Reward to other use cases.

3.3. Hook Stage Pattern Conclusion

We draw conclusions based on the statistics (shown in Figure 5) of external and internal transitions. Figure 5a shows the internal pattern visualization. Statistics are provided in the graph in Figure 3. Figure 5b shows the total number of internal (pink) and external (green) transitions.

Figure 5.

Statistics visualization of Hook cycle patterns.

Internal occurs within one use case, thus one Hook cycle. Figure 5c shows the proportion of transitions, internal and external, that occur while moving from one Hook stage to another. We are mostly interested in performing analysis on this scheme.

Internal transitions: For both cases the transition sets are the same: Trigger–Action–Investment, Action–Investment, Trigger–Action–Reward, Trigger–Action–Investment–Reward. The proportion of TAI and AI differs greatly (Table 2); however, in sum these patterns make the same proportion of all presented patterns. The proportions of TAR and TARI are almost the same correspondingly for both products. This means that internal use cases for both cases could be designed applying Hook model patterns (TAI, TAR, TAIR, AI) with the same frequency of use (illustrated in the graph in Figure 3). The point is only that delighters include more Investment-containing use cases with Triggers, because through this Trigger a habit of use, a need, or a pain that could be solved via the application is formed.

External transitions: For Instagram and Uber taxi, the external transitions’ presence proportions do vary. Only the transition Investment–Trigger has a similar proportion of presence (around 46%). For Instagram, the percentage of Investment–Investment transition is only 7.5%, whereas for Uber taxi it is high, 35%. Reward–Trigger for Instagram, on the contrary, is even more frequent than I–T—in 47.5% of cases. This means that in Instagram in the use cases chain, a new use case rarely starts without the participation of an internal Trigger, while in Uber they can more often advance through an application use case without additional internal Triggers. Thus, we can conclude that Uber actually needs fewer Triggers in designing the use cases because the application brings the user through the stages to receive the profit, the need for which triggered the user to initiate the interaction with the app. Moreover, the fact that the proportion of R–T transitions is two times less for Uber means that after receiving the Reward, the user stays and continues doing something in the app more rarely than the same happens in Instagram. Recall that the proportion of use cases that includes a Reward stage is the same for both types of products. This means that Instagram users are more likely to leave right after they obtain the Reward—they just do not return to application use with an internal Trigger. However, increasing the number of internal Triggers for applications such as Uber taxi might not be conceptually correct, because initially, this type of application’s goal is to serve, not to keep the user inside the app. External Triggers, both in-app or outside, could be a good solution for bringing a user back.

However, some service applications (e.g., fintech services) increase internal Triggers’ number while designing (stories, advertisement feature) to increase the time spent on the app, and this is a part of a monetization strategy based on advertising, self, and partners. With services such as Uber, it is generally an easier process of creating a habit of use: there is a profit, so the user will return, recommend it to others, etc. The user experience is important so that everything is “all-inclusive", seamless, and hassle-free, but this is a question of service design and UX design (this is also common for applications such as Instagram). Thus, the Hook model is not essential for the design of applications such as Uber taxi. However, the Hook model is successfully applied by the definition of Uber’s use cases, although we do not have data that could confirm that Uber was designed according to the Hook model.

4. Discussion

Having studied the applications of the Hook model, we analyzed the internal and external patters of the Hook stages in Instagram and Uber. Internal patterns are the combination of the Hook cycle stage inside one use case (Table 2), while external patterns are the transitions between use cases (Table 3).

Table 3.

Statistics on transitions between UCs, also known as external patterns.

Based on the analysis of internal patterns, we conclude that Uber is in less need of triggers than Instagram (Table 2). In Instagram, each action is preceded by a trigger, resulting in the prevalence of Trigger–Action–Investment (TAI) patterns, while Uber has an equal proportion of TAI and Action–Investment (AI) patterns. There is also a higher proportion of Trigger–Action–Reward–Investment (TARI) patterns (full cycles) for Instagram. Less complicated AI pattern Actions are common for Uber: they are the part of the decomposition of the process that the user must go through to receive the service, and the user does not need to spend extra strength for an emotional reaction. The initial Trigger that prompted the user to use the service is enough. An Investment-containing use case occurred 1.7 times more often than a Reward. The Action stage was present in each use case; a Trigger occurred in each for Instagram, but not so frequently for Uber. The proportion of Investment-containing patterns is greater than that for Reward. Thus, Investment increases the value of a product and keeps their interest in the application use via variability of the Reward: the user knows that they could receive the Reward, but this does not happen often; thus, they continue attempts to do so.

External patterns (transitions between use cases) demonstrate a similar trend with the prevalence of Triggers in Instagram. Instagram mostly transitions between the use cases to the Trigger stage, because the user does not have a specific purpose. For Uber, a chain of Investment–Investment external transition is characteristic because the user goes to the end of the chain of Actions to receive the service, and this simplifies the interaction—they do not need to experience unnecessary Triggers; the first Trigger of service is enough to obtain a result. In Uber, the Reward–Trigger transition is not so common: in fact, the Uber use-case graph has fewer connecting edges than that of Instagram, and Instagram has more options for what to do next after a certain use case.

As a result of the analysis, we created an elaborate scheme (Figure 6) of how the two products’ functionalities incorporate the Hook model stages. The scheme reflects the mechanism for the formation of internal Triggers, various Investment options, and transformation of Rewards. This section includes the underlying mechanism (Figure 6) and several key observations on how the Hook model is applied in the two case-study products.

Figure 6.

The Hook cycle mechanism observed during the case study.

4.1. Use External Triggers “Within” the Product to Promote or Diverge Usage Scenarios

Through the investigation, we have discovered that triggers can be placed within the product such that certain actions can be prompted or reinforced during the product use. This further adds to the notion of Triggers as formulated by Fogg [] and adopted by Eyal [].

An external Trigger prompts the user to perform an action and is part of the environment or the product. The goal is to appeal to the associative memory and provoke an internal Trigger, which is the user’s internal desire to perform the action. Importantly, external Triggers can be both “outside” and “within” the product. The former try to engage the user to use the product (e.g., notification, icon, email, mention in another application or verbal communication, etc.), while the latter are those that stimulate user advancement through user scenarios during the interaction with the product (tips, instructions, clickable objects).

An external Trigger during the use of an IT product can be any interactive element within the product as long as it possesses the characteristics of discoverability and understandability []—in other words, if the user (a) can discover it on the screen (UI) and (b) understands that it can be clicked on and what will happen after (UX). Further, an external Trigger can both change the scenario of user behavior (e.g., watched story, went to private messages for discussion) and promote the user along the chain of use cases within one scenario (e.g., searched for an account by the nickname, opened an account, subscribed, opened a post, etc.).

The habituation still requires the creation of internal Triggers, as it reduces the cost of creating external Triggers, since the user forms a connection between using the product and relieving pain/receiving pleasure. An internal Trigger prompts the user to take an Action. Of course, this also poses ethical considerations, for which we have mentioned related work in the first section of the article.

4.2. An Investment Embedded in an Action Allows Us to Plant an Additional Trigger

Investment plays a critical role in the Hook model—the number of use cases with it is 1.7 times higher than the number of use cases with Reward. By definition, it is a “footprint” left by the user in the system: adjusting the environment (adding content, comments, friends (communication channels), editing personal account settings, etc.), time spent.

Interestingly, Investment is often embedded in the Action stage. An Action can result in an Investment when: (a) time and effort are spent on the Action, (b) personal data are shared that make the experience and product’s value higher, or (c) the user grows in the mastery of the product.

Furthermore, the Investment can lead to the creation of Triggers by the user themself. At the Investment stage, the following Triggers can be created: (1) an internal Trigger for the user, if the execution of the Action did not lead to an immediate Reward and requires time (user writes a post and needs to go back and check how subscribers reacted, how many likes, what comments); or (2) an external Trigger for other users, if the result of the Action’s execution can be viewed and commented on in the sense of feedback (user writes a post and subscribers see it (external Trigger)). This external Trigger is associated with the internal one; therefore, it calls this internal Trigger, which already provokes the user (one of those, others) on the Action (saw the post—you need to look—like or comment). Thus, Investment for one user can be an external Trigger for other users if the result of the user’s activity is visible to them (e.g., message—another user Triggered to perform an Action: open app and message, read, and possibly reply).

This observation demonstrates how Investment is used to initiate new Hook cycles. The repetition of cycles is the key to habit formation, as is emphasized by Eyal [] and Yao [].

4.3. Failing to Receive a Reward Can Serve as a Trigger

Importantly, within the context of social media platforms such as Instagram, the failure to receive the Reward for an Action can become a trigger in itself in certain cases. When a user takes an Action and receives a Reward, an associative relationship is formed between the performed behavior (the path from Trigger to Reward through Action) and the Reward received, expressed in a sense of self-worth, acceptance by society, releasing pain or fear of being rejected, and delight of hope and acceptance. At the level of physiology, a neural connection is formed that will work the next time when the same Trigger is encountered on the user’s path, thus provoking the behavior; at the level of behaviorism, a connection is formed between the stimulus (Trigger) and response (behavior). This ensures that the user will re-initiate the Hook cycle in the future. Thus, the variability and distribution of the Reward can also be a significant factor.

However, if the Reward is not achieved as a result of Action performance, there are two options. The first option is that a new internal Trigger of dissatisfaction is created that prompts the user to make another attempt to obtain the Reward, thus launching the next cycle (e.g., when looking through the suggestions on Instagram, a user continues to search and scroll because they hope that soon they finally should find something interesting; thus, the cycles are running one after another). Another option of behavior when the user does not receive the Reward is that they could leave the application, especially if they are not habituated to using it. To prevent this, external Triggers should be applied: notifications, emails, and even the icon on the main screen of the phone could help. The same approach is valid when a user leaves the application in any cycle stage, so they do not perform the cycle completely. This is needed to bring the user back to application use.

4.4. Ethics behind the Hook Model

Services should satisfy users’ needs and try to produce positive emotions []. Applications such as Uber serve the actual need of users. The hook is designed to form an internal Trigger so when the context of their occurrence arises the service can satisfy the user’s need. Instagram plays, on the contrary, on dissatisfaction with the variety of the Reward. When a user orders a taxi, the user expects that it will arrive and, if it does not, the user will be dissatisfied. When a user scrolls through Instagram in search of an interesting post, they also expect to find an interesting post. However, if the posts were all entirely interesting, after a while the user would have received good emotions and left Instagram. Therefore, since finding an interesting post is uncritical, the user continues to scroll the feed in the hope of finding something worthwhile.

In general, applications that resolve a real problem appeal to the positive emotions of people, because without receiving a solution to their real problem, users leave, while social services can use the feeling of dissatisfaction and the variability of the Reward to promote further use. It appears that one class of applications is ethical and the other is not. However, as we remember, issues of ethics are not legally regulated (if its violation occurs within the framework of legal methods) and remain on the conscience of the author of the product []. The use of the Hook model can be questioned in this context, because it is used mainly to transform the services into applications that create a habit or create a need for use. Further investigation is required to assess the ethics of using the Hook model in applications such as Instagram and to suggest best practices and guidelines.

5. Conclusions

The Hook model allows businesses to increase user engagement and retention by habituating the users to the product. In this study, we examined how the model is applied in two case study applications, namely Instagram and Uber, the former being a social network and the latter a taxi service. We looked into the functionality of the applications and reverse-engineered the use cases. Then we analyzed how the four stages of the Hook model are integrated into the use cases with the goal of identifying the patterns within each application. We drew the following insights from the comparison of the two applications.

Instagram more heavily relies on triggers, both within a single use case and also to transition between use cases. It appears that Uber requires fewer triggers as users come with a specific goal in mind. Moreover, the UI and functionality within the product can serve as Triggers that promote certain usage scenarios or drive the scenario into a new one. Any clickable interface element can serve as a Trigger if it is discoverable and the associated functionality is understandable.

Investment plays a crucial role in both products and is more prevalent than reward by 1.7 times. It is often embedded within Actions and can also be used to create new external Triggers for the user themself and for other users. The most important role of the Investment is to promote future Hook cycles to build the habit and association between a need and the product.

Uber requires a stable delivery of the Reward as the result of an Action, otherwise it risks losing users due to dissatisfaction. However, Instagram can use failure to deliver a reward as an internal trigger itself, as the failure to deliver allows for the variability of the Reward. An important question for future research can be what is the optimal variability ratio, how it should be calculated, and what are the effects on the user. Importantly, we highlight the greater relevance of ethical consideration in the case of Instagram, as it appears to exploit the users’ dissatisfaction and triggers to engage the users.

Lastly, future research should explore the Hook model patterns in other applications, as the results of the current study are based on the study of two specific cases, which limits the possibility of generalization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.L. and N.A.; methodology, E.L.; investigation, resources, data curation, and validation, E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L.; formal analysis and writing—review and editing, N.A. and H.A.; visualization, E.L. and N.A.; supervision, M.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

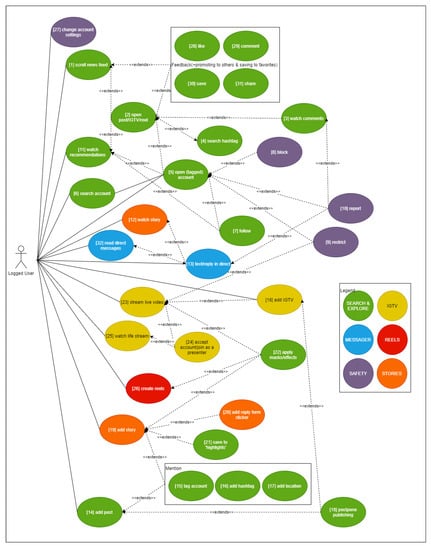

Appendix A. Use Case Diagrams

Figure A1.

Uber taxi registered user (rider) use case diagram.

Figure A2.

Visualization of Hook model stages mapped to Uber registered user (rider) use cases.

Figure A3.

Instagram registered user use case diagram.

Figure A4.

Visualization of Hook model stages mapped to Instagram registered user use cases.

References

- Muller, A.; Välikangas, L.; Merlyn, P. Metrics for innovation: Guidelines for developing a customized suite of innovation metrics. Strategy Leadersh. 2005, 33, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, N. Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oulasvirta, A.; Rattenbury, T.; Ma, L.; Raita, E. Habits make smartphone use more pervasive. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2012, 16, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhtusova, Y.; Megha, S.; Askarbekuly, N. A case study on combining agile and user-centered design. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Frontiers in Software Engineering, Innopolis, Russia, 17–18 June 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Duhigg, C. The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov, P.I. Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Ann. Neurosci. 2010, 17, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coon, D.; Mitterer, J. Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and Behavior with Concept Maps and Reviews; MindTap Course List Series; Cenage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fogg, B.J. Persuasive computers: Perspectives and research directions. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 18–23 April 1998; pp. 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Eyal, N. Notifications that Work. 2019. Available online: https://www.nirandfar.com/notifications-that-work/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Neal, D.; Wood, W. How do habits guide behavior? Perceived and actual triggers of habits in daily life. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Finkenauer, C. Bad Is Stronger Than Good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg, B. Fogg Behavior Model. Available online: https://behaviordesign.stanford.edu/resources/fogg-behavior-model (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Fogg, B. Prompts Tell People to “Do It Now!”. Available online: http://www.behaviormodel.org/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Pimenov, D.; Solovyov, A.; Askarbekuly, N.; Mazzara, M. Data-Driven Approaches to User Interface Design: A Case Study. J. Phys. 2021, 2134, 12020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, B.F. Reinforcement today. Am. Psychol. 1958, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, J. Supercharging New Users’ Desire with Variable Rewards. Available online: https://www.appcues.com/blog/variable-rewards (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Breuning, L.G. Habits of a Happy Brain: Retrain Your Brain to Boost Your Serotonin, Dopamine, Oxytocin, & Endorphin Levels; Adams Media: Avon, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Uusiautti, S. On the positive connection between success and happiness. Int. J. Res. Stud. Psychol. 2013, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langvardt, K. Regulating habit-forming technology. Fordham Law Rev. 2019, 88, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, P.P. Persuasive Technology and Moral Responsibility Toward an ethical framework for persuasive technologies. Persuasive 2006, 6, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Askarbekuly, N.; Sadovykh, A.; Mazzara, M. Combining two modelling approaches: GQM and KAOS in an open source project. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Conference on Open Source Systems, Virtual, 12–13 May 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 106–119. [Google Scholar]

- Askarbekuly, N.; Solovyov, A.; Lukyanchikova, E.; Pimenov, D.; Mazzara, M. Building an educational product: Constructive alignment and requirements engineering. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–24 July 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 358–365. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, A.; Johnson, W.C. Designing and Delivering Superior Customer Value: Concepts, Cases, and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Filippou, J.; Cheong, C.; Cheong, F. Combining the fogg behavioural model and hook model to design features in a persuasive app to improve study habits. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.03531. [Google Scholar]

- Razi, A.A.; Putra, R.P. The hooked model as communication strategy of “Kembaliin” app as an information media for handling lost and found. In Proceedings of the 2nd Social and Humaniora Research Symposium (SoRes 2019), Bandung, Indonesia, 23 October 2019; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 214–218. [Google Scholar]

- De Troyer, O.; Maushagen, J.; Lindbeg, R.; Muls, J.; Signer, B.; Lombaerts, K. A playful mobile digital environment to tackle school burnout using micro learning, persuasion & gamification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), Maceio, Brazil, 15–18 July 2019; Volume 2161, pp. 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Li, T.M. Develop habit-forming products based on the Axiomatic Design Theory. Procedia CIRP 2016, 53, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertemel, A.V.; Aydın, G. Technology addiction in the digital economy and suggested solutions. Addicta Turk. J. Addict. 2018, 5, 665–690. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, D. How to Build a Habit-forming Product-to Understand the Hook Model through an Analysis of WeChat. Shodai Bus. Rev. 2018, 7, 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- StatCounter. Desktop, Mobile, Tablet Platform Market Share Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/platform-market-share/desktop-mobile-tablet (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- StatCounter. OS Market Share Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share/mobile/worldwide (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Instagram Statistics. 2020. Business of Apps. Available online: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/instagram-statistics/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Uber Statistics. 2020. Business of Apps. Available online: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/uber-statistics/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Norman, D. The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, S.M.; Johnston, R.; Duffy, J.; Rao, J. The service concept: The missing link in service design research? J. Oper. Manag. 2002, 20, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).