Enablers and Barriers in FinTech Adoption: A Systematic Literature Review of Customer Adoption and Its Impact on Bank Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: Which enablers and barriers affect FinTech adoption from a consumer perspective?

- RQ2: How does FinTech adoption influence bank performance?

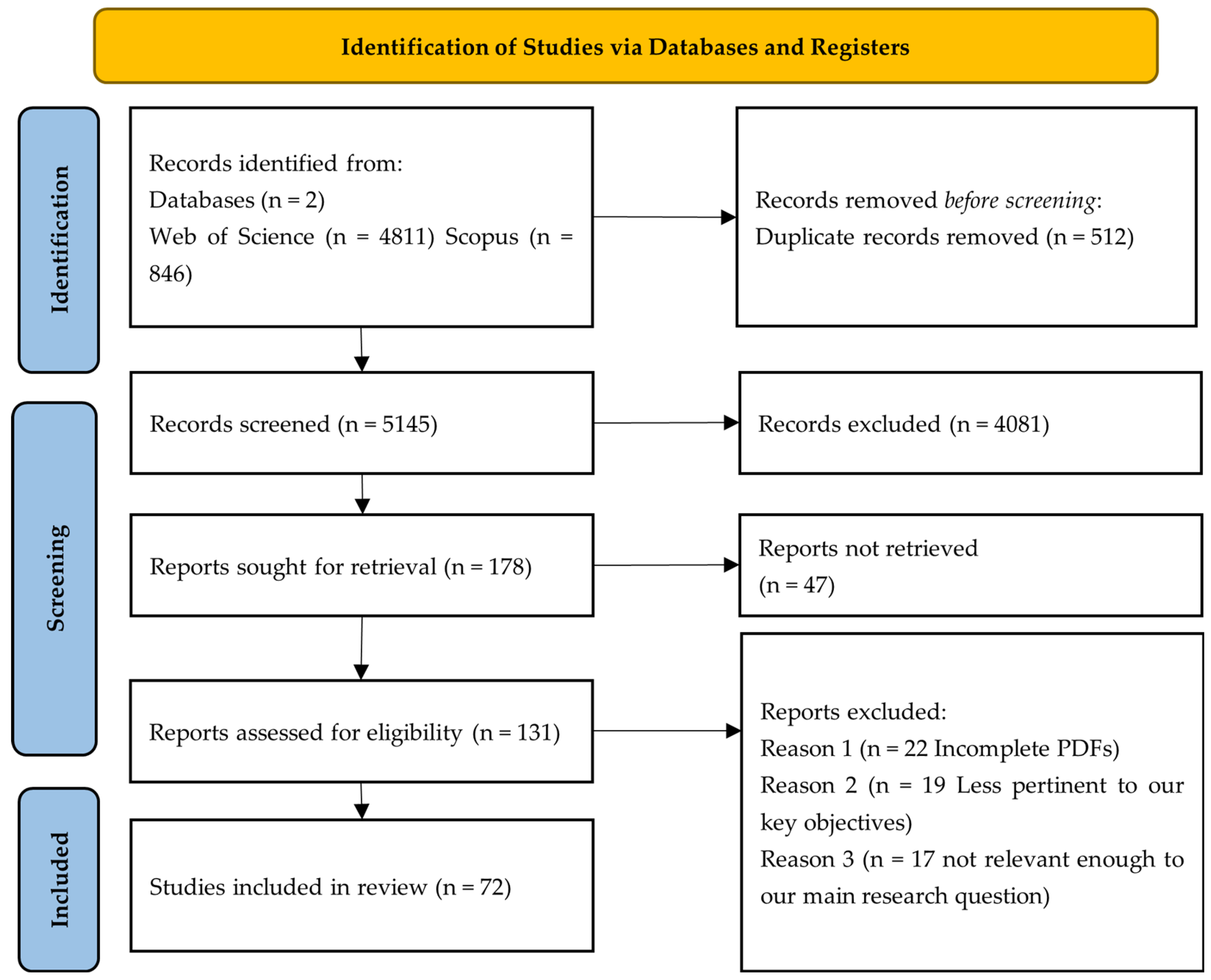

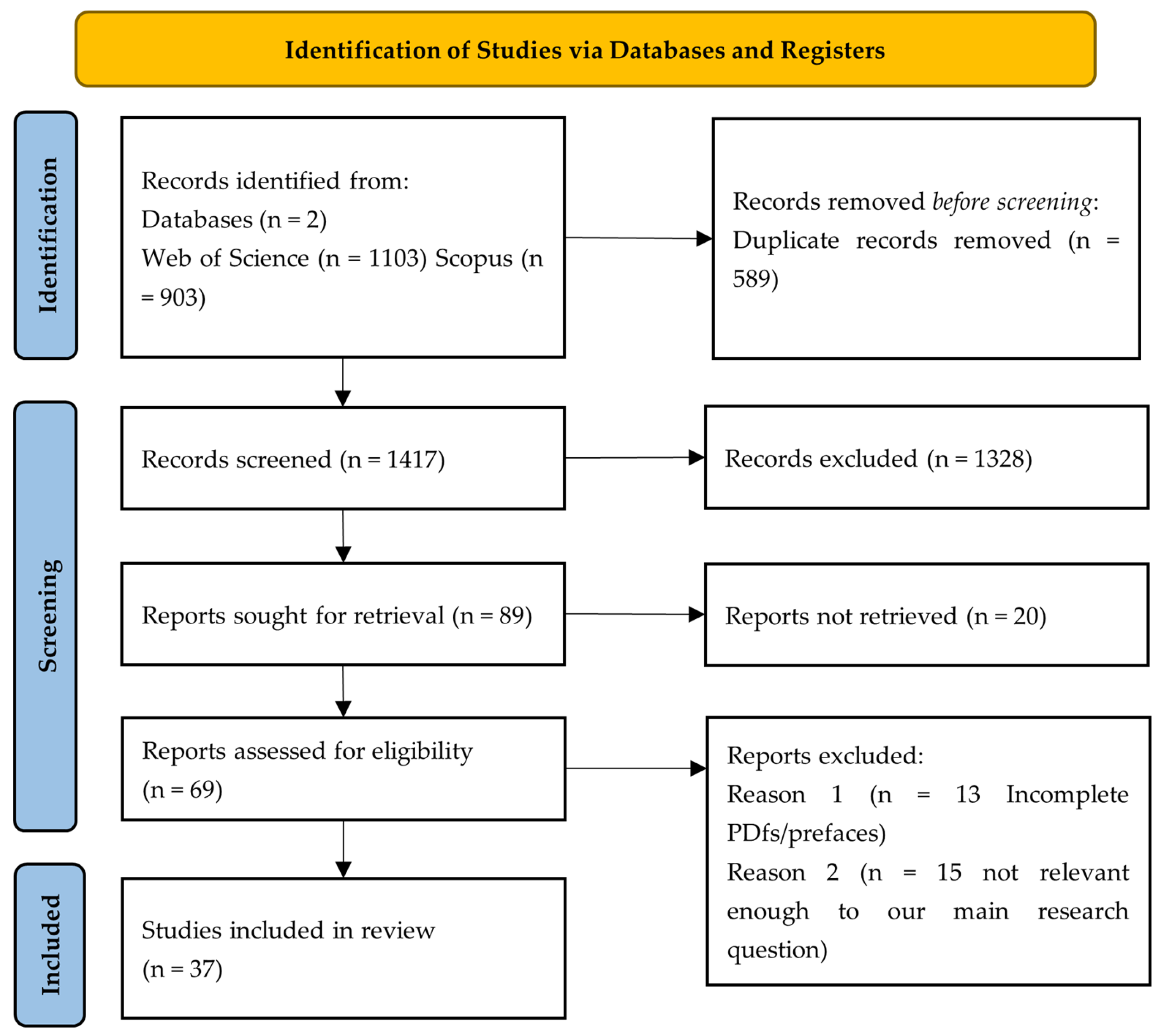

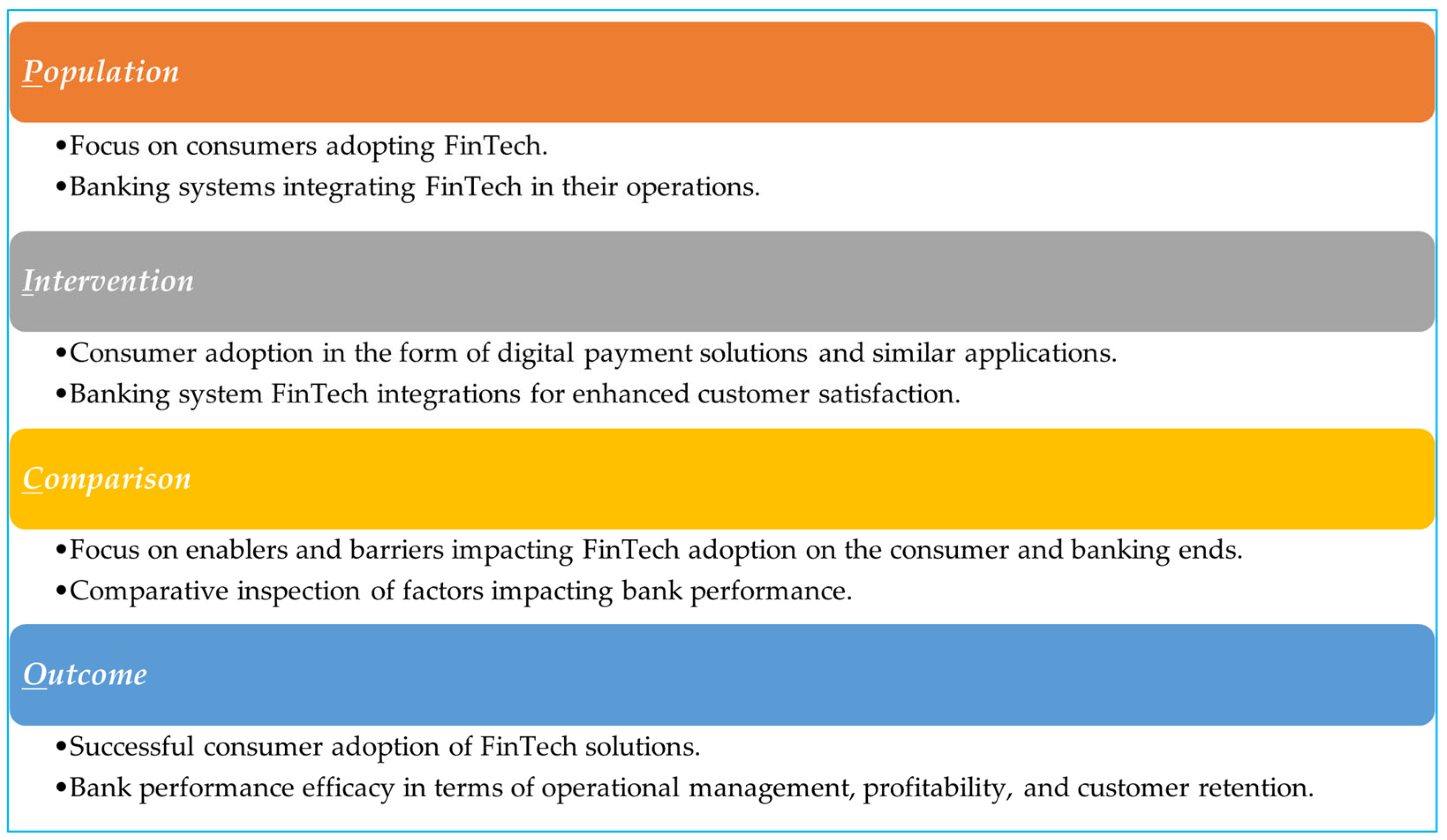

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Source and Research Strategy

2.4. Research Strings

3. Results

3.1. Theories Used

3.2. Context

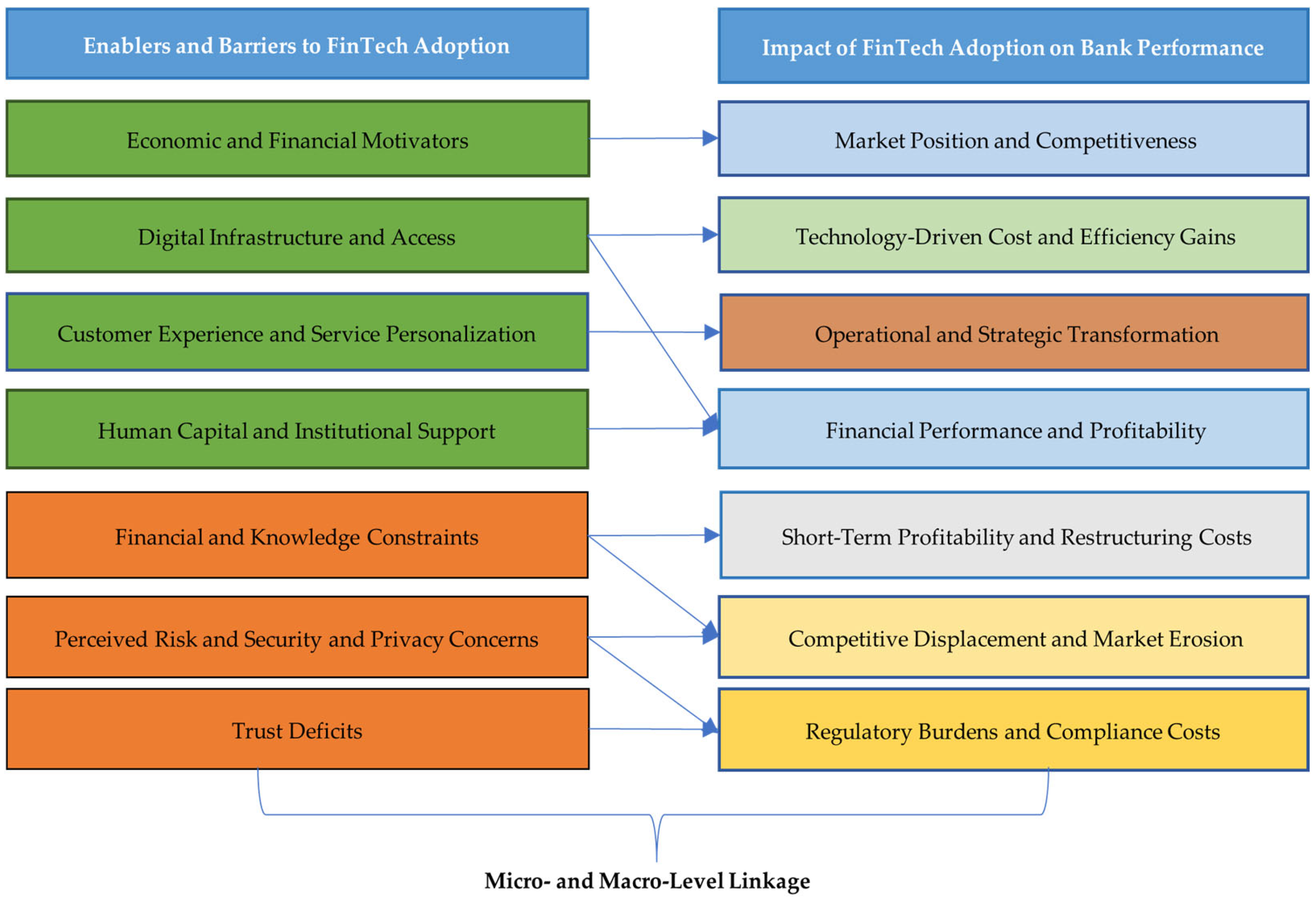

3.3. Enablers and Barriers in FinTech Adoption

- Economic factors: High transaction costs, cost-effectiveness, incentives, and increased revenue and profitability;

- Technological factors: Internet and technology accessibility limited financial and digital literacy, smartphones, internet penetration, and personalized and AI-driven services;

- Regulatory factors: Security concerns, trust and security improvements, financial and digital literacy, convenience and accessibility, government regulatory support, and improved customer experience and retention;

- Behavioral factors: Lack of trust, social influence, and improved customer experience and retention;

- Other factors: Enhanced operational efficiency and business model shifts.

3.4. Impact of FinTech Adoption on Bank Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Thematic Synthesis for RQ1: Enablers of FinTech Adoption

4.1.1. Theme 1: Economic and Financial Motivators

4.1.2. Theme 2: Digital Infrastructure and Access

4.1.3. Theme 3: Customer Experience and Service Personalization

4.1.4. Theme 4: Human Capital and Institutional Support

4.2. Barriers to FinTech Adoption

4.2.1. Theme 1: Financial and Knowledge Constraints

4.2.2. Theme 2: Perceived Risk and Security and Privacy Concerns

4.2.3. Theme 3: Trust

4.2.4. Integrated Theoretical Insights

4.3. Thematic Synthesis for RQ2: Impact of FinTech on Bank Performance

4.3.1. Positive Impacts (Enablers of Bank Performance)

Theme 1: Financial Performance and Profitability

Theme 2: Operational and Strategic Transformation

Theme 3: Market Position and Competitiveness

Theme 4: Technology-Driven Cost and Efficiency Gains

4.3.2. Negative Impacts (Barriers and Challenges)

Theme 1: Short-Term Profitability and Restructuring Costs

Theme 2: Competitive Displacement and Market Erosion

Theme 3: Regulatory Burdens and Compliance Costs

4.4. Integrative Insights: Linking FinTech Adoption Drivers to Bank Performance

5. Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical and Policy Implications

6. Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Search Strings | Search Date | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY((“fintech*” OR “financial technolog*” OR “digital bank*” OR “mobile bank*” OR “online bank*” OR “payment technolog*” OR “crowdfunding*” OR “peer-to-peer lending*” OR “digital payment*”) AND (“adopt*” OR “accept*” OR “use*” OR “uptake” OR “customer adoption” OR “consumer adoption” OR “user adoption” OR “user acceptance”) AND (“enabl*” OR “driver*” OR “facilitat*” OR “motivator*” OR “support*” OR “promot*” OR “success factor*” OR “barrier*” OR “challenge*” OR “obstacl*” OR “hindrance*” OR “constraint*” OR “risk*” OR “resist*” OR “limitation*”) AND (“survey” OR “case study” OR “empirical study” OR “quantitative analysis")) AND PUBYEAR > 2014 AND NOT (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Islamic finance” OR “Islamic fintech” OR “green finance” OR “systematic review”)) | 23 December 2024 | 846 articles |

| Web of Science | TS=(“fintech*” OR “financial technolog*” OR “digital bank*” OR “mobile bank*” OR “online bank*” OR “payment technolog*” OR “crowdfunding*” OR “peer-to-peer lending*” OR “digital payment*”) AND TS=(“adopt*” OR “accept*” OR “use*” OR “uptake” OR “customer adoption” OR “consumer adoption” OR “user adoption” OR “user acceptance”) AND TS=(“enabl*” OR “driver*” OR “facilitat*” OR “motivator*” OR “support*” OR “promot*” OR “success factor*” OR “barrier*” OR “challenge*” OR “obstacl*” OR “hindrance*” OR “constraint*” OR “risk*” OR “resist*” OR “limitation*”) AND PY=(2014-2025) AND TS=(“survey” OR “case study” OR “empirical study” OR “quantitative analysis”) NOT TS=(“Islamic finance” OR “Islamic fintech” OR “green finance” OR “systematic review”) | 23 December 2024 | 4811 articles |

| Database | Search Strings | Search Date | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY((“fintech*” OR “financial technolog*” OR “digital bank*” OR “mobile bank*” OR “online bank*” OR “payment technolog*” OR “peer-to-peer lending*” OR “crowdfunding*” OR “digital payment*") AND (“bank performance” OR “financial performance” OR “profitability” OR “efficiency” OR “return on assets” OR “ROA” OR “return on equity” OR “ROE” OR “net interest margin” OR “NIM” OR “operational efficiency” OR “loan quality” OR “market share” OR “stability")) AND PUBYEAR > 2014 AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Islamic finance” OR “Islamic fintech” OR “green finance” OR “blockchain” OR “cryptocurrency” OR “systematic review”) AND (LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE, “ar”)) | 1 January 2025 | 903 articles |

| Web of Science | TS=(“fintech*” OR “financial technolog*” OR “digital bank*” OR “mobile bank*” OR “online bank*” OR “payment technolog*” OR “peer-to-peer lending*” OR “crowdfunding*” OR “digital payment*”) AND TS=(“bank performance” OR “financial performance” OR “profitability” OR “efficiency” OR “return on assets” OR “ROA” OR “return on equity” OR “ROE” OR “net interest margin” OR “NIM” OR “operational efficiency” OR “loan quality” OR “market share” OR “stability”) AND PY=(2014-2025) NOT TS=(“Islamic finance” OR “Islamic fintech” OR “green finance” OR “blockchain” OR “cryptocurrency” OR “systematic review”) | 1 January 2025 | 1103 |

| Journal Name | Publisher | Best Scopus Quartile |

|---|---|---|

| International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management | Springer | Q3 (Engineering) |

| Humanities and Social Sciences Communications | Springer Nature | Q1 (Social Sciences) |

| Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication | Emerald | Q2 (Information Science) |

| International Review of Management and Marketing | Econ Journals | Q4 (Business, Economics) |

| Journal of Risk and Financial Management | MDPI | Q2 (Finance) |

| Sustainability | MDPI | Q2 (Environmental Science) |

| International Journal of Information Management Data Insights | Elsevier | New (Not yet ranked) |

| Financial Innovation | Springer | Q1 (Finance) |

| Paper Asia | Research India Publications | Not indexed (Scopus) |

| Journal of Marketing Analytics | Palgrave Macmillan (Springer) | Q3 (Marketing) |

| Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity | Elsevier | Q2 (Business, Innovation) |

| Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship | Springer | Q2 (Business, Management) |

| Journal of Financial Services Marketing | Palgrave Macmillan | Q3 (Marketing, Finance) |

| International Journal of Bank Marketing | Emerald | Q2 (Business, Finance) |

| Journal of Islamic Marketing | Emerald | Q2 (Business, Marketing) |

| Journal of Modelling in Management | Emerald | Q3 (Management) |

| International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal | Springer | Q2 (Business, Management) |

| International Journal of Emerging Markets | Emerald | Q2 (Business, Economics) |

| Scientific Papers of the University of Pardubice, Series D: Faculty of Economics and Administration | University of Pardubice | Q4 (Economics) |

| Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies | Wiley | Q2 (Psychology, Technology) |

| Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja | Taylor & Francis | Q3 (Economics) |

| Journal of Global Marketing | Taylor & Francis | Q3 (Marketing) |

| International Journal of Business Information Systems | Inder Science | Q3 (Information Systems) |

| Technology in Society | Elsevier | Q1 (Social Sciences, Technology) |

| International Journal of Information Management | Elsevier | Q1 (Information Systems) |

| Benchmarking: An International Journal | Emerald | Q2 (Business, Management) |

| Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business | Korea Distribution Science Association | Q3 (Economics, Finance) |

| African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development | Taylor & Francis | Q3 (Innovation, Development) |

| Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues | Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Center | Q3 (Business, Sustainability) |

| International Journal of Computing and Digital Systems | University of Bahrain | Q3 (Computer Science) |

| International Journal of Business & Management Science | Asian Economic and Social Society | Not indexed (Scopus) |

| Spanish Journal of Marketing | Emerald | Q2 (Marketing) |

| Review of International Business and Strategy | Emerald | Q2 (Business, Strategy) |

| Journal of Social and Economic Development | Springer | Q3 (Economics, Development) |

| Computers in Human Behavior | Elsevier | Q1 (Psychology, Technology) |

| Digital Business | Elsevier | New (Not yet ranked) |

| Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review | Cracow University of Economics | Q2 (Business, Economics) |

| Heliyon | Elsevier | Q2 (Multidisciplinary) |

| Journal of Enterprise Information Management | Emerald | Q2 (Information Systems) |

| Information & Computer Security | Emerald | Q2 (Cybersecurity) |

| SAGE Open | SAGE | Q2 (Social Sciences) |

| Social Sciences | MDPI | Q2 (Social Sciences) |

| Economies | MDPI | Q2 (Economics) |

| The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research | Taylor & Francis | Q3 (Business, Marketing) |

| Frontiers in Psychology | Frontiers Media | Q1 (Psychology) |

| Aslib Journal of Information Management | Emerald | Q2 (Information Science) |

| Global Business Review | SAGE | Q3 (Business, Economics) |

| Management Decision | Emerald | Q1 (Business, Management) |

| Journal of Advances in Management Research | Emerald | Q3 (Management) |

| Environmental Science and Pollution Research | Springer | Q2 (Environmental Science) |

| Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance | Elsevier | Q2 (Finance, Behavioral Economics) |

| International Journal of Data and Network Science | Growing Science | Q2 (Computer Science) |

| International Journal of Financial Studies | MDPI | Q2 (Economics, Finance) |

| Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development | Elsevier | Q2 (Economics, Development) |

| International Journal of Sustainable Development | Inderscience | Q3 (Environmental Science) |

| International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance | Inderscience | Q3 (Economics, Finance) |

| Asian Economic and Financial Review | AESS Publications | Q3 (Economics, Finance) |

| Banks and Bank Systems | Business Perspectives | Q3 (Finance, Banking) |

| Pacific-Basin Finance Journal | Elsevier | Q1 (Finance) |

| Journal of the Knowledge Economy | Springer | Q2 (Economics, Innovation) |

| Journal of Global Information Management | IGI Global | Q2 (Information Systems) |

| Cogent Economics & Finance | Taylor & Francis | Q2 (Economics, Finance) |

| Technological Forecasting and Social Change | Elsevier | Q1 (Business, Innovation) |

| Journal of International Money and Finance | Elsevier | Q1 (Finance) |

| International Review of Economics & Finance | Elsevier | Q2 (Economics, Finance) |

| European Management Journal | Elsevier | Q1 (Business, Management) |

| European Journal of Innovation Management | Emerald | Q2 (Business, Innovation) |

| International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences | Elsevier | Q3 (Multidisciplinary) |

| Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting | Springer | Q2 (Finance, Accounting) |

| International Journal of e-Collaboration | IGI Global | Q3 (Information Technology) |

References

- Arner, D.W.; Barberis, J.; Buckley, R.P.; Arner, D.; Barberis, J. FinTech, RegTech, and the Reconceptualization of Financial Regulation. Northwest J. Int. Law Bus. 2017, 37, 371. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.A.; Wu, Q.; Yang, B. How Valuable Is FinTech Innovation? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 2062–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, X. The Impact of Fintech on Banking—European Economy. 2017. Available online: https://european-economy.eu/2017-2/the-impact-of-fintech-on-banking/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Firmansyah, E.A.; Masri, M.; Anshari, M.; Besar, M.H.A. Factors Affecting Fintech Adoption: A Systematic Literature Review. FinTech 2022, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornuf, L.; Safari, K.; Voshaar, J. Mobile fintech adoption in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 73, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarawneh, A.; Abdul-Rahman, A.; Amin, S.I.M.; Ghazali, M.F. A Systematic Review of Fintech and Banking Profitability. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2024, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Kasperskaya, Y.; Sagarra, M. The impact of FinTech on bank performance: A systematic literature review. Digit. Bus. 2025, 5, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.; Le, P.; Nguyen, D.K. Financial inclusion and fintech: A state-of-the-art systematic literature review. Financ. Innov. 2025, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, N.; Bajaj, P.K.; Saxena, D. Fintech Innovation, Financial Performance and Stability: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Abhigyan 2025, 43, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Castañeda, V. Disadvantages in preparing and publishing scientific papers caused by the dominance of the English language in science: The case of Colombian researchers in biological sciences. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Omar, N.A. Integrating TPB, TAM and DOI theories: An empirical evidence for the adoption of mobile banking among customers in Klang valley, Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2018, 8, 385–403. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Yu, C.-H.; Chen, S.; Lee, C.-C. Riding the FinTech innovation wave: FinTech, patents and bank performance. J. Int. Money Financ. 2022, 122, 102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, A.F.; Ekaputra, I.A.; Japutra, A. Adoption of FinTech Products: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Creat. Commun. 2021, 16, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsepe, N.T.; Van der Lingen, E. Determinants of emerging technologies adoption in the South African financial sector. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2022, 53, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milian, E.Z.; Spinola, M.d.M.; de Carvalho, M.M. Fintechs: A literature review and research agenda. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 34, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.; Parmar, B.J.; Zalavadia, U. Assessment of Omni channel retailing characteristics and its effect on consumer buying intention. Sci. Temper 2024, 15, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.H.; Ahmad, A.H.; Masri, R.; Chong, C.V.; Ula, R.; Fauzi, A.; Idris, I. Evolution of Technology and Consumer Behaviour. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 3206–3217. [Google Scholar]

- Koskelainen, T.; Kalmi, P.; Scornavacca, E.; Vartiainen, T. Financial literacy in the digital age—A research agenda. J. Consum. Aff. 2023, 57, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.; Rahmani, S. Beyond Traditional Banking: How Fintech is Reshaping Financial Access in India. IARJSET 2025, 12, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wang, G.; Huang, C. What promotes the mobile payment behavior of the elderly? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhwaldi, A.F.; Al-Qudah, A.A.; Al-Hattami, H.M.; Al-Okaily, M.; Al-Adwan, A.S.; Abu-Salih, B. Uncertainty avoidance and acceptance of the digital payment systems: A partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) approach. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2024, 73, 1119–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qudah, A.A.; Al-Okaily, M.; Shiyyab, F.S.; Taha, A.A.D.; Almajali, D.A.; Masa’deh, R.; Warrad, L.H. Determinants of Digital Payment Adoption Among Generation Z: An Empirical Study. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Fatima, J.K. Influence of perceived value on omnichannel usage: Mediating and moderating roles of the omnichannel shopping habit. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, S.K.; Kochhar, K. Financial equality through technology: Do perceived risks deter Indian women from sustained use of mobile payment services? Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2024, 4, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igamo, A.M.; Al Rachmat, R.; Siregar, M.I.; Gariba, M.I.; Cherono, V.; Wahyuni, A.S.; Setiawan, B. Factors influencing Fintech adoption for women in the post-Covid-19 pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhajjar, S.; Ouaida, F. An analysis of factors affecting mobile banking adoption. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 38, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobti, N. Impact of demonetization on diffusion of mobile payment service in India. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2019, 16, 472–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmadi, A.A.; Alrawashdeh, N.; Al-Gasaymeh, A.; Al-Malahmeh, H.; Al, A.M. Impact of business enablers on banking performance: A moderating role of Fintech. Banks Bank Syst. 2023, 18, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafeef, M.A.; Kalyebara, B.; Kalbouneh, N.Y.; Abuoliem, N.; Yousef, A.N.B.; Al-Afeef, M.A.M. The impact of FINTECH on banking performance: Evidence from middle eastern countries. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2024, 8, 2219–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, H.A.; Alqubaysi, R.; Musa, A.M.H.; Boreik, D.A.S. The effect of financial technology on the financial performance of national Saudi banks. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2024, 8, 1399–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Yu, H.; He, Z. Heterogeneous Impact of Fintech on the Profitability of Commercial Banks: Competition and Spillover Effects. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-K. Financial Innovation, Financial Patents and Business Performance: An Empirical Study on the Banking Industry in Taiwan. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2022, 12, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, B.S. The role of e-payments in enhancing financial performance: A case study of the Bank of Palestine. Banks Bank Syst. 2021, 16, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, D.H.B.; Narayan, P.K.; Rahman, R.E.; Hutabarat, A.R. Do financial technology firms influence bank performance? Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2020, 62, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.H.; Khan, S.; Ghafoor, A. Fintech adoption, the regulatory environment and bank stability: An empirical investigation from GCC economies. Borsa Istanbul Rev. 2023, 23, 1263–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljawder, M.; Abdulrazzaq, A. The Effect of Awareness, Trust, and Privacy and Security on Students’ Adoption of Contactless Payments: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2019, 8, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, L.J.; Xu, X.; Hung, T.H.B. Impact of Financial Digitalization on Organizational Performance. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2022, 30, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Malik, P.; Gautam, S. Customer experience and loyalty analysis with PLS-SEM digital payment loyalty model. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2024, 15, 5469–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faudzi, M.S.M.; Bakar, L.J.A.; Ahmad, S. Breaking Barriers: Investigating Technology Adoption in Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) Among Low-Income Women Entrepreneurs in Malaysia. PaperASIA 2024, 40, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Sikarwar, P.; Mishra, A.; Raghuwanshi, S.; Singhal, A.; Joshi, A.; Singh, P.R.; Dixit, A. Determinants of Behavioral Intention to Use Digital Payment among Indian Youngsters. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, S.; Arora, R. Adoption of mobile banking at the bottom of the pyramid: An emerging market perspective. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Taieh, E.M.; AlHadid, I.; Abu-Tayeh, S.; Masa’deh, R.; Alkhawaldeh, R.S.; Khwaldeh, S.; Alrowwad, A. Continued Intention to Use of M-Banking in Jordan by Integrating UTAUT, TPB, TAM and Service Quality with ML. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Sanchís-Pedregosa, C.; Paredes, J.R.P. Online banking adoption in Spanish cities and towns. Finding differences through TAM application. Econ. Res. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 854–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Amin, M.; Arefin, M.S.; Alam, M.S.; Rasul, T.F. Understanding the Predictors of Rural Customers’ Continuance Intention toward Mobile Banking Services Applications during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Glob. Mark. 2022, 35, 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.C.; Wu, C.-G.; Lee, C.-S.; Pham, T.-T.T. Factors affecting the behavioral intention to adopt mobile banking: An international comparison. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyei, J.; Sun, S.; Abrokwah, E.; Penney, E.K.; Ofori-Boafo, R. Mobile Banking Adoption: Examining the Role of Personality Traits. Sage Open 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Govindaluri, S.M.; Al-Muharrami, S.; Tarhini, A. A multi-analytical model for mobile banking adoption: A developing country perspective. Rev. Int. Bus. Strateg. 2017, 27, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.M.; Vu, T.-M.-H.; Luu, T.-M.-N.; Dang, T.H. Factors affecting digital banking services acceptance: An empirical study in Vietnam during the COVID-19 pandemic. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2024, 12, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnasamy, G.; Vinoth, S.; Jain, A. Revolutionizing Finance: A Comprehensive Analysis of Digital Banking Adoption and Impact. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2024, 1–12. Available online: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3984531/v1 (accessed on 16 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Sharma, M. Examining the role of trust and quality dimensions in the actual usage of mobile banking services: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P.P.; Williams, M.D. Consumer adoption of mobile banking in Jordan. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2016, 29, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritha, P.H. Mobile payment service adoption: Understanding customers for an application of emerging financial technology. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2023, 31, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, A.W.; Donghong, D.; Umrani, W.A.; Siyal, S.; Bhand, S. Predicting Mobile Banking Acceptance and Loyalty in Chinese Bank Customers. Sage Open 2019, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silanoi, W.; Naruetharadhol, P.; Ponsree, K. The Confidence of and Concern about Using Mobile Banking among Generation Z: A Case of the Post COVID-19 Situation in Thailand. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Siddik, A.B.; Akter, N.; Dong, Q. Factors influencing the adoption intention of using mobile financial service during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of FinTech. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 30, 61271–61289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almubarak, A.I.; Aljughaiman, A.A. Corporate Governance and FinTech Innovation: Evidence from Saudi Banks. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryono; Hamzah, M.Z.; Sofilda, E.; Herlianto, A. Indonesian Banking Policy in The Digital Era and Its Impact on Competition in the Banking Industry. OIDA Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 17, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kaddumi, T.A.; Baker, H.; Nassar, M.D.; A-Kilani, Q. Does Financial Technology Adoption Influence Bank’s Financial Performance: The Case of Jordan. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.; Kaddumi, T.A.; Nassar, M.D.; Muqattash, R.S. Impact of Financial Technology on Improvement of Banks’ Financial Performance. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shouha, L.; Khasawneh, O.; El-qawaqneh, S.; Al-Naimi, A.A.; Saram, M.; Ismail, W.N.S.W. The impact of financial technology on bank performance in Arabian countries. Banks Bank Syst. 2024, 19, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, D.; Aljughaiman, A.A.; Papavassiliou, V. Does financial technology matter? Evidence from an alternative banking system. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2021, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; You, X.; Chang, V. FinTech and commercial banks’ performance in China: A leap forward or survival of the fittest? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olalere, O.E.; Kes, M.S.; Islam, M.A.; Rahman, S. The Effect of Financial Innovation and Bank Competition on Firm Value: A Comparative Study of Malaysian and Nigerian Banks. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Li, X.; Yu, C.-H.; Zhao, J. Does fintech innovation improve bank efficiency? Evidence from China’s banking industry. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 74, 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gaudio, B.L.; Porzio, C.; Sampagnaro, G.; Verdoliva, V. How do mobile, internet and ICT diffusion affect the banking industry? An empirical analysis. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, C.; Catuogno, S.; Naciti, V. Governing FinTech for performance: The monitoring role of female independent directors. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattass, M.I. The impact of digital evolution and FinTech on banking performance: A cross-country analysis. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2023, 10, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.P.; Huynh, H.T.; Popesko, B.; Hoang, S.D.; Tran, T.B. Impact of Fintech’s Development on Bank Performance: An Empirical Study from Vietnam. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2024, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Ye, L.; Wen, G.-F.; Wang, R. Do Commercial Banks Benefit From Bank-FinTech Strategic Collaboration? Int. J. e-Collab. 2022, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elangovan, A.; Babu, M. Decoding Users’ Continuance Intentions towards Digital Financial Platforms in the Indian Economy. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2024, 14, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Pereira, M.S.; Silva, A.; Souza, A.; Oliveira, I.; Figueiredo, J. The Influence of Digital Influencers on Generation Y’s Adoption of Fintech Banking Services in Brazil. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, B.-O.; Juan, L.-R.; Ana, I.-D.; Francisco, L.-C. Examining user behavior with machine learning for effective mobile peer-to-peer payment adoption. Financ. Innov. 2024, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ma, J.; Huang, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, T. Extend UTAUT2 Model to Analyze User Behavior of China Construction Bank Mobile App. Sage Open 2024, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendrinos, K.; Spais, G. An investigation of selected UTAUT constructs and consumption values of Gen Z and Gen X for mobile banking services and behavioral intentions to facilitate the adoption of mobile apps. J. Mark. Anal. 2024, 12, 492–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chan, T.J. Predictors of Mobile Payment Use Applications from the Extended Technology Acceptance Model: Does Self-Efficacy and Trust Matter? Sage Open 2024, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnas, M.B.; Selvam, M.; Parayitam, S. FinTech and Financial Inclusion: Exploring the Mediating Role of Digital Financial Literacy and the Moderating Influence of Perceived Regulatory Support. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.E.; Palaniappan, S. Using a technology acceptance model to determine factors influencing continued usage of mobile money service transactions in Ghana. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, T.I.; Jaafar, J.A.; Aziz, N.A.A. What factors influence the usage of mobile banking among digital natives? J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2023, 28, 763–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Biswas, A. Does M-payment service quality and perceived value co-creation participation magnify M-payment continuance usage intention? Moderation of usefulness and severity. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2023, 41, 1330–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenizi, A.S. Understanding the subjective realties of social proof and usability for mobile banking adoption: Using triangulation of qualitative methods. J. Islam. Mark. 2023, 14, 2027–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Otaibi, S.; Shishakly, R.; Hassan, L.; Lutfi, A.; Alrawad, M.; Qatawneh, M.; Alghanam, O.A. Investigating the Role of Perceived Risk, Perceived Security and Perceived Trust on Smart m-Banking Application Using SEM. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Sharma, P. A study of Indian Gen X and Millennials consumers’ intention to use FinTech payment services during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Model. Manag. 2023, 18, 1177–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Navalón, J.-G.; Fernández-Fernández, M.; Alberto, F.P. Does privacy and ease of use influence user trust in digital banking applications in Spain and Portugal? Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 781–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, M.S.; Saleh, N.S.; Ali, A.M.; Bakar, S.A. Factors Determining the Acceptance of E-Wallet among Gen Z from the Lens of the Extended Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chan, T.J.; Suki, N.M.; Kasim, M.A. Moderating Role of Perceived Trust and Perceived Service Quality on Consumers’ Use Behavior of Alipay e-wallet System: The Perspectives of Technology Acceptance Model and Theory of Planned Behavior. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 2023, 527640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.-X.; Lin, H.-C. Predictors of customers’ continuance intention of mobile banking from the perspective of the interactivity theory. Econ. Res. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 6820–6849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhawaldeh, A.M.; Matar, A.; Al Rdaydeh, M. Intention to use mobile banking services: Extended model. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2022, 39, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okocha, F.O.; Adibi, V.A. Mobile banking adoption by business executives in Nigeria. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2020, 12, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaziri, R.; Miralam, M. Modelling the crowdfunding technology adoption among novice entrepreneurs: An extended tam model. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 6, 2159–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baabdullah, A.M.; Alalwan, A.A.; Rana, N.P.; Kizgin, H.; Patil, P. Consumer use of mobile banking (M-Banking) in Saudi Arabia: Towards an integrated model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Climent-Climent, S.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Determinants of intention to use the mobile banking apps: An extension of the classic TAM model. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2017, 21, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, S.; Devesh, S.; Al Lawati, A.M. What factors drive the adoption of digital banking? An empirical study from the perspective of Omani retail banking. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2020, 25, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khobragade, A.; Balachandran, R.; Gupta, B.; Saroy, R.; Awasthy, S.; Singh, G.; Misra, R.; Dhal, S. Mobile banking adoption for financial inclusion: Insights from rural West Bengal. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 2024, 27, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnemer, H.A. Determinants of digital banking adoption in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A technology acceptance model approach. Digit. Bus. 2022, 2, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Joshi, H. Consumer perspectives about mobile banking adoption in India—A cluster analysis. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 616–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Maryam, S.Z.; Shaheen, W.A. Cognitive factors and actual usage of Fintech innovation: Exploring the UTAUT framework for digital banking. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Sreejesh, S. Examining the role of customers’ intrinsic motivation on continued usage of mobile banking: A relational approach. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2022, 40, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhi, M.; Hone, K.; Tarhini, A. A cross-cultural study of the intention to use mobile banking between Lebanese and British consumers: Extending UTAUT2 with security, privacy and trust. Technol. Soc. 2019, 59, 101151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuong, N.V.; Phuong, N.T.T.; Liem, N.T.; Thuy, C.T.M.; Son, T.H. Factors Affecting the Intention to Use Financial Technology among Vietnamese Youth: Research in the Time of COVID-19 and Beyond. Economies 2022, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.A.; Bonifield, C.M.; Arias, A.; Villegas, J. Mobile payment adoption in Latin America. J. Serv. Mark. 2022, 36, 1058–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Kiani, U.S.; Raza, B.; Mustafa, A. Consumers’ Intention to Adopt m-payment/m-banking: The Role of Their Financial Skills and Digital Literacy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 873708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Joshi, H. The moderating role of gender and age in the adoption of mobile wallet. Foresight 2020, 22, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Joshi, H. Attitude as a mediator between antecedents of mobile banking adoption and user intention. Int. J. Bus. Excell. 2021, 24, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sahni, M.M.; Kovid, R.K. What drives FinTech adoption? A multi-method evaluation using an adapted technology acceptance model. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 1675–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daragmeh, A.; Lentner, C.; Sági, J. FinTech payments in the era of COVID-19: Factors influencing behavioral intentions of “Generation X” in Hungary to use mobile payment. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2021, 32, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garškaitė-Milvydienė, K.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Impact of bank financial technology on the performance of banks in the European Union. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 8053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarah, B.A.F.; Alghadi, M.Y.; Al-Zaqeba, M.A.A.; Mugableh, M.I.; Zaqaibeh, B. The influence of financial technology on profitability in Jordanian commercial banks. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Lett. 2024, 12, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Rahman, M.A.; Hossain, S.; Moudud-Ul-Huq, S. Does Fintech-Driven Inclusive Finance Induce Bank Profitability? Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Lee, H.; Oh, I. Differential Impact of Fintech and GDP on Bank Performance: Global Evidence. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, S.A. E-Payment Technology Effect on Bank Performance in Emerging Economies–Evidence from Nigeria. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhaidar, A.; Abdelhedi, M.; Abdelkafi, I. The Effect of Financial Technology Investment Level on European Banks’ Profitability. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 14, 2959–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwateng, K.O.; Osei-Wusu, E.E.; Amanor, K. Exploring the effect of online banking on bank performance using data envelopment analysis. Benchmarking An Int. J. 2019, 27, 137–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiampa, P.; McGuinness, P.B.; Serbera, J.-P.; Zhao, K. The financial and prudential performance of Chinese banks and Fintech lenders in the era of digitalization. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2022, 58, 1451–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Saleem, S.; Shabbir, R.; Shabbir, M.S.; Irshad, A.; Khan, S. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A moderate role of fintech technology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 20174–20187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ky, S.S.; Rugemintwari, C.; Sauviat, A. Is Fintech Good for Bank Performance? The Case of Mobile Money in the East African Community. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2024. Early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, S.A.; Jamal, Y.; Ullah, S. FinTech adoption, HR competency potential, service innovation and firm growth in banking sector. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Zhang, J. FinTech, Lending and Payment Innovation: A Review. Asia-Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2020, 49, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, P.; Alabdooli, J.I.; Dwivedi, R. Role of FinTech Adoption for Competitiveness and Performance of the Bank: A Study of Banking Industry in UAE. Int. J. Glob. Bus. Compet. 2021, 16, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Khaliq, N. In quest of perceived risk determinants affecting intention to use fintech: Moderating effects of situational factors. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 207, 123599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warokka, A.; Setiawan, A.; Aqmar, A.Z. Key Factors Influencing Fintech Development in ASEAN-4 Countries: A Mediation Analysis. FinTech 2025, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J. The economic forces driving fintech adoption across countries. In The Technological Revolution in Financial Services: How Banks, FinTechs, and Customers Win Together; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Cananda, 2020; pp. 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroline, S.; Putri, A.; Oei, E.; Verawati, V.; Isnovian, I. Differences of Individual Demographic Characteristics Towards E-Wallet Payment in Restaurants. Asean Mark. J. 2021, 12, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero-Prisno, D.E.; Olayemi, A.H.; Ekpenyong, I.; Okereke, P.; Aldirdiri, O.; Buban, J.M.; Ndikumana, S.; Yelarge, K.; Sesay, N.; Turay, F.U.; et al. Prospects for financial technology for health in Africa. Digit. Heal. 2022, 8, 205520762211195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, L.B.; Amajuoyi, P.; Adeusi, K.B. Marketing, communication, banking, and Fintech: Personalization in Fintech marketing, enhancing customer communication for financial inclusion. Int. J. Manag. Entrep. Res. 2024, 6, 1687–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aro, O.E. Data analytics as a driver of digital transformation in financial institutions. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 24, 1054–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, D.W.; Aryanti, R.K. The Influence of Financial Technology in Financial Transactions. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 662, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borole, P. A Critical Review on Omni—Channel Marketing Communications in Financial, Retail, and Healthcare Services. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2022, 11, 1555–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, G.; Lu, Y. FinTech: A literature review of emerging financial technologies and applications. Financ. Innov. 2025, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.S. The Role of AI-Enhanced Personalization in Customer Experiences. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2024, 6, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansurali, A.; Stephen, G.; Kasilingam, D.; Jublee, D.I. Omnichannel marketing: A systematic review and research agenda. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2024, 34, 616–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msweli, N.T.; Mawela, T. Enablers and Barriers for Mobile Commerce and Banking Services Among the Elderly in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Banerji, P. Systematic literature review on Digital Financial Literacy. SN Bus. Econ. 2024, 4, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayagopal, P.; Jain, B.; Viswanathan, S.A. Regulations and Fintech: A Comparative Study of the Developed and Developing Countries. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istanbul Rev. 2018, 18, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.; Jamil, R. A Systematic Literature Review of the Gig Economy: Insights into Worker Experiences, Policy Implications, and the Impact of Digitalization. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2025, IX, 2136–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnas, M.B.; Selvam, M.; Raja, M.; Santhoshkumar, S.; Parayitam, S. Understanding the Determinants of FinTech Adoption: Integrating UTAUT2 with Trust Theoretic Model. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, D.I.; Srivastava, D.N.; Mishra, P.A.; Adhav, D.S.; Singh, M.N. The Rise of Fintech: Disrupting Traditional Financial Services. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 2024, 30, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M.; Chekima, B.; Lajuni, N.; Anwar, A. Understanding Consumers’ Barriers to Using FinTech Services in the United Arab Emirates: Mixed-Methods Research Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatorachian, H.; O’Higgins, B.; Maldonado, A.; Lyons, C.; Willis, H.; Abbott, L.; Brooks, M. Navigating the challenges of FinTech startups in the B2C market. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Morris, N.P.; McNiel, D.E.; Binder, R. Elder Financial Exploitation in the Digital Age. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2023, 51, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, I. The Moderating effect of Digital and Financial Literacy on the Digital Financial Services and Financial Behavior of MSMEs. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 20, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, N.P.A.; Akhtar, S.M.J. Digital Financial Literacy and Its Determinants: An Empirical Evidences from Rural India. South Asian J. Soc. Stud. Econ. 2021, 11, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al nawayseh, M.K. FinTech in COVID-19 and Beyond: What Factors Are Affecting Customers’ Choice of FinTech Applications? J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirani, Y.; Randi, R.; Romadhon, M.S.; Suhendi, S. The influence of familiarity and personal innovativeness on the acceptance of fintech lending services: A perspective from Indonesian borrowers. Regist. J. Ilm. Teknol. Sist. Inf. 2021, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaiya, O.P.; Adesoga, T.O.; Adebayo, A.A.; Sotomi, F.M.; Adigun, O.A.; Ezeliora, P.M. Encryption techniques for financial data security in fintech applications. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 12, 2942–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, U.; Mohnot, R.; Singh, H.V.; Banerjee, A. The Mediating Effect of Perceived Trust in the Adoption of Cutting-Edge Financial Technology among Digital Natives in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Economies 2023, 11, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.; Gupta, L.; Zameni, A. Fintech and Islamic Finance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, A.; Sucahyo, Y.G. Architecting an Advanced Maturity Model for Business Processes in the Gig Economy: A Platform-Based Project Standardization. Economies 2021, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furquim, T.S.G.; da Veiga, C.P.; da Veiga, C.R.P.; da Silva, W.V. The Different Phases of the Omnichannel Consumer Buying Journey: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Directions. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 18, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gohary, H.; Thayaseelan, A.; Babatunde, S.; El-Gohary, S. An Exploratory Study on the Effect of Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Technology on Customer Experiences in the Banking Sector. J. Technol. Adv. 2021, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinčević, I.; Črnjević, S.; Klopotan, I. Novelties and Benefits of Fintech in the Financial Industry. Int. J. E-Serv. Mob. Appl. 2022, 14, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.Y.; Molyneux, P.; Pancotto, L.; Reghezza, A. Banks and FinTech Acquisitions. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 2024, 65, 41–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridan, N.M.; Hassan, A.F.S.; Alahmadi, H.A. Financial Technology Inclusion in Islamic Banks: Implication on Shariah Compliance Assurance. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, A.G.; Huseynov, F. The Causal Relationship between FinTech, Financial Inclusion, and Income Inequality in African Economies. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărăcine, V.; Voican, O.; Scarlat, E. The Digital Transformation and Disruption in Business Models of the Banks under the Impact of FinTech and BigTech. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2020, 14, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.M.S.; Chowdhury, M.A.M.; Razak, D.B.A. Research evolution in banking performance: A bibliometric analysis. Futur. Bus. J. 2021, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, S.; Mahmoood, W. Impact of Corporate Governance & Capital Structure on Firm Financial Performance: Evidence from Listed Cement Sector of Pakistan. J. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2018, 44, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Litimi, H.; BenSaïda, A.; Raheem, M.M. Impact of FinTech Growth on Bank Performance in GCC Region. J. Emerg. Mark. Financ. 2024, 23, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shari, H.A.; Lokhande, M.A. The relationship between the risks of adopting FinTech in banks and their impact on the performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparin, I.; Slongo, L.A. Omnichannel as a Consumer-Based Marketing Strategy. Rev. Adm. Contemp. 2023, 27, e220327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Research Question 1 | Research Question 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | Exclusion | Inclusion | Exclusion | |

| Study design | Modern comparable methodologies with advanced statistics and well-reputed designs. | Weak/old study designs. | Modern comparable methodologies with advanced statistics and well-reputed designs. | Weak/old study designs. |

| Study focus | Studies that explicitly discuss consumer adoption of FinTech services or technologies. | Articles discussing the corporate adoption or technological development of FinTech without focusing on consumers. Articles related to Islamic finance/FinTech and green and energy-related finance. | Studies explicitly analyzing the relationship between FinTech adoption and bank performance. | Articles focusing on FinTech consumer adoption without exploring bank performance. Studies discussing FinTech in industries other than banking. Articles related to Islamic finance/FinTech and green and energy-related finance. |

| Publication Type | Journals containing research articles that only include empirical data, emphasizing quantitative studies. | Journals excluded from indexing, systematic literature review publications, and book chapters. | Indexed journals containing research articles that only include empirical data, emphasizing quantitative studies. | Incomplete abstracts, commentaries, and short papers. Journals excluded from indexing, systematic literature review publications, and book chapters. Conference proceedings and papers centered around conceptual discussions. |

| Key disciplines | Articles from business, management, economics, finance, and social sciences. | Other disciplines. | Articles from business, management, economics, finance, and social sciences. | Other disciplines. |

| Language | Articles in English only (or easily translatable to English). | Articles in any language other than English. | Articles in English only. | Articles in any language other than English. |

| Time frame | 2016–2024 | |||

| Sr # | Theory | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) | 48 |

| 2 | Extended Technology Acceptance Model (Extended TAM) | 11 |

| 3 | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) | 6 |

| 4 | Extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT2) | 4 |

| 5 | Stimulus–Organism–Response (S-O-R) Model | 2 |

| 6 | Information Systems Success Model (ISSM) | 2 |

| 7 | Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) | 5 |

| 8 | Diffusion of Innovations (DOIs) | 3 |

| 9 | SERVQUAL (Service Quality Model) | 1 |

| 10 | Risk Perception Theory | 2 |

| 11 | Continuance Usage Intention Framework | 1 |

| 12 | Hofstede’s Cross-Cultural Dimension (Uncertainty Avoidance—UA) | 1 |

| 13 | Trust Theory | 1 |

| 14 | Task–Technology Fit (TTF) Model | 1 |

| 15 | Decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior | 1 |

| 16 | Meta-UTAUT Model | 1 |

| 17 | Trust-Based Technology Acceptance Model (TB-TAM) | 1 |

| 18 | DeLone & McLean Information Systems (D&M ISs) Success Model | 1 |

| 19 | Self-Determination Theory (SDT) | 1 |

| 20 | Interactivity Theory | 1 |

| 21 | Theoretical Framework on Financial Inclusion Through FinTech | 1 |

| 22 | Consumer Behavior and Influencer Marketing Theories (implied) | 1 |

| 23 | Theories about Customer Behavior in Response to Technological Innovations (implied) | 1 |

| 24 | Resource Dependency Theory | 1 |

| 25 | Agency Theory | 2 |

| 26 | Socio-Technical Systems Theory | 1 |

| 27 | Strategic Alliance Theory | 1 |

| Country | Frequency | Country | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| India | 21 | Seville (city in Spain) | 1 |

| China | 12 | Greece | 1 |

| Jordan | 10 | Kuwait | 2 |

| Malaysia | 6 | Algeria | 1 |

| Thailand | 1 | Taiwan | 1 |

| Not Specified | 4 | Nigeria | 3 |

| Ghana | 3 | Tunisia | 1 |

| Spain | 2 | Bahrain | 3 |

| Saudi Arabia | 4 | Oman | 4 |

| Vietnam | 4 | Iran | 1 |

| United States | 2 | Lebanon | 2 |

| Pakistan | 3 | United Kingdom | 1 |

| Bangladesh | 2 | Thailand | 1 |

| Indonesia | 2 | Hungary | 1 |

| Brazil | 1 | International (multiple countries) | 1 |

| Latvia | 1 | United Arab Emirates | 4 |

| Malaysia and Nigeria | 1 | Portugal | 1 |

| International (multiple countries) | 1 | Europe | 1 |

| European Union | 1 | Italy | 1 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa, specifically focusing on the East African community | 1 | Palestine Hungary | 1 1 |

| Author and Date of Publication | Research Question 1: Enablers and Barriers in FinTech Adoption | Research Question 2: Impact of FinTech on Bank Performance | Ref. | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enablers of FinTech Adoption | Barriers to FinTech Adoption | Positive Impact | Negative Impact | ||||||||||||

| Economic and Financial Motivators | Digital Infrastructure and Access | Customer Experience and Service Personalization | Human Capital and Institutional Support | Financial and Knowledge Constraints | Perceived Risk and Security and Privacy Concerns | Trust | Financial Performance and Profitability | Operational and Strategic Transformation | Market Position and Competitiveness | Technology-Driven Cost and Efficiency Gains | Short-Term Profitability and Restructuring Costs | Competitive Displacement and Market Erosion | Regulatory Burdens and Compliance Costs | ||

| (Huang, Wang, and Huang 2024) | √ | [20] | |||||||||||||

| (Alkhwaldi et al., 2024) | √ | [21] | |||||||||||||

| (Al-Qudah et al., 2024) | √ | √ | √ | [22] | |||||||||||

| (N. Sharma and Fatima 2024) | √ | √ | [23] | ||||||||||||

| (P. Yadav et al., 2024) | √ | √ | [24] | ||||||||||||

| (Igamo et al., 2024) | √ | √ | [25] | ||||||||||||

| (Elhajjar and Ouaida 2019) | √ | [26] | |||||||||||||

| (Sobti 2019) | √ | [27] | |||||||||||||

| (Abdalmajeed Alsmadi et al., 2023) | [28] | ||||||||||||||

| (Alafeef et al., 2024) | √ | [29] | |||||||||||||

| (Alqahtani et al., 2024) | √ | [30] | |||||||||||||

| (Song, Yu, and He 2023) | √ | √ | [31] | ||||||||||||

| (T.-K. Liu 2022) | √ | [32] | |||||||||||||

| (Sobhi Awwad 2021) | √ | [33] | |||||||||||||

| (Phan et al., 2020) | √ | [34] | |||||||||||||

| (Maan et al., 2019) | √ | √ | [36] | ||||||||||||

| (Wang et al., 2022) | √ | [37] | |||||||||||||

| (Shilpa Agarwal, Malik, and Gautam 2024) | √ | √ | [38] | ||||||||||||

| (Md Faudzi, Abu Bakar, and Ahmad 2024) | √ | √ | [39] | ||||||||||||

| (Hasan et al., 2024) | √ | √ | [40] | ||||||||||||

| (Purohit and Arora 2023) | √ | √ | [41] | ||||||||||||

| (Abu-Taieh et al., 2022) | √ | √ | [42] | ||||||||||||

| (Albort-Morant, Sanchís-Pedregosa, and Paredes Paredes 2022) | √ | [43] | |||||||||||||

| (Al Amin et al., 2022) | √ | √ | [44] | ||||||||||||

| (Ho et al., 2020) | √ | [45] | |||||||||||||

| (Agyei et al., 2020) | √ | √ | [46] | ||||||||||||

| (S. K. Sharma et al., 2017) | √ | [47] | |||||||||||||

| (Nguyen et al., 2024) | √ | [48] | |||||||||||||

| (Chinnasamy, S, and Jain 2024) | √ | √ | [49] | ||||||||||||

| (S. K. Sharma and Sharma 2019) | √ | √ | [50] | ||||||||||||

| (Alalwan et al., 2016) | √ | √ | [51] | ||||||||||||

| (P.H. 2023) | √ | √ | [52] | ||||||||||||

| (Siyal et al., 2019) | √ | √ | √ | [53] | |||||||||||

| (Silanoi, Naruetharadhol, and Ponsree 2023) | √ | √ | √ | √ | [54] | ||||||||||

| (Yan et al., 2021) | √ | √ | [55] | ||||||||||||

| (Almubarak and Aljughaiman 2024) | √ | [56] | |||||||||||||

| (Haryono et al., 2024) | √ | √ | [57] | ||||||||||||

| (Kaddumi et al., 2023) | √ | √ | [58] | ||||||||||||

| (Baker et al., 2023) | √ | √ | [59] | ||||||||||||

| (Al-Shouha et al., 2024) | √ | √ | [60] | ||||||||||||

| (Almulla and Aljughaiman 2021) | √ | √ | [61] | ||||||||||||

| (Xihui Chen, You, and Chang 2021) | √ | √ | [62] | ||||||||||||

| (Olalere et al., 2021) | √ | √ | √ | [63] | |||||||||||

| (Lee et al., 2021) | √ | √ | √ | [64] | |||||||||||

| (Del Gaudio et al., 2021) | √ | √ | [65] | ||||||||||||

| (Arena, Catuogno, and Naciti 2023) | √ | √ | [66] | ||||||||||||

| (Alattass 2023) | √ | [67] | |||||||||||||

| (Pham et al., 2024) | √ | √ | [68] | ||||||||||||

| (Fang et al., 2022) | √ | √ | √ | [69] | |||||||||||

| (Elangovan and Babu 2024) | √ | √ | [70] | ||||||||||||

| (Cardoso et al., 2024) | √ | √ | [71] | ||||||||||||

| (Antonio et al., 2024) | √ | √ | √ | [72] | |||||||||||

| (Jiang et al., 2024) | √ | √ | √ | [73] | |||||||||||

| (Dendrinos and Spais 2024) | √ | [74] | |||||||||||||

| (Tian and Chan 2024) | √ | √ | √ | [75] | |||||||||||

| (Amnas, Selvam, and Parayitam 2024) | √ | √ | [76] | ||||||||||||

| (Kelly and Palaniappan 2023) | √ | √ | √ | [77] | |||||||||||

| (Hakimi, Jaafar, and Aziz 2023) | √ | [78] | |||||||||||||

| (Kumari and Biswas 2023) | √ | √ | [79] | ||||||||||||

| (Alenizi 2023) | √ | √ | [80] | ||||||||||||

| (Almaiah et al., 2023) | √ | [81] | |||||||||||||

| (A. K. Singh and Sharma 2023) | √ | √ | [82] | ||||||||||||

| (Martínez-Navalón, Fernández-Fernández, and Alberto 2023) | √ | √ | [83] | ||||||||||||

| (Rosli et al., 2023) | √ | √ | √ | [84] | |||||||||||

| (Tian et al., 2023) | √ | √ | [85] | ||||||||||||

| (Yin and Lin 2022) | √ | [86] | |||||||||||||

| (Alkhawaldeh, Matar, and Rdaydeh 2022) | √ | √ | [87] | ||||||||||||

| (Okocha and Awele Adibi 2020) | √ | √ | [88] | ||||||||||||

| (Jaziri and Miralam 2019) | √ | [89] | |||||||||||||

| (Baabdullah et al., 2019) | √ | [90] | |||||||||||||

| (Muñoz-Leiva, Climent-Climent, and Liébana-Cabanillas 2017) | √ | √ | √ | [91] | |||||||||||

| (Ananda, Devesh, and Al Lawati 2020) | √ | [92] | |||||||||||||

| (Khobragade et al., 2024) | √ | √ | [93] | ||||||||||||

| (Alnemer 2022) | √ | √ | √ | [94] | |||||||||||

| (D. Chawla and Joshi 2017) | √ | √ | [95] | ||||||||||||

| (Tariq, Maryam, and Shaheen 2024) | √ | [96] | |||||||||||||

| (Banerjee and Sreejesh 2022) | √ | [97] | |||||||||||||

| (Merhi, Hone, and Tarhini 2019) | √ | √ | [98] | ||||||||||||

| (Khuong et al., 2022) | √ | √ | √ | √ | [99] | ||||||||||

| (Bailey et al., 2022) | [100] | ||||||||||||||

| (Ullah et al., 2022) | √ | √ | [101] | ||||||||||||

| (D. Chawla and Joshi 2020) | √ | [102] | |||||||||||||

| (D. Chawla and Joshi 2021) | √ | √ | [103] | ||||||||||||

| (S. Singh, Sahni, and Kovid 2020) | √ | √ | √ | [104] | |||||||||||

| (Daragmeh, Lentner, and Sági 2021) | √ | √ | √ | [105] | |||||||||||

| (Garškaitė-Milvydienė and Tvaronavičienė 2024) | √ | [106] | |||||||||||||

| (Jarah et al., 2024) | √ | √ | √ | [107] | |||||||||||

| (Zheng et al., 2023) | √ | √ | √ | [108] | |||||||||||

| (Yoon, Lee, and Oh 2023) | √ | √ | [109] | ||||||||||||

| (Mustapha 2018) | √ | [110] | |||||||||||||

| (Chhaidar, Abdelhedi, and Abdelkafi 2023) | √ | [111] | |||||||||||||

| (Owusu Kwateng, Osei-Wusu, and Amanor 2019) | √ | [112] | |||||||||||||

| (J. Zhao et al., 2022) | √ | [12] | |||||||||||||

| (Katsiampa et al., 2022) | √ | [113] | |||||||||||||

| (Y. Liu et al., 2021) | √ | √ | √ | [114] | |||||||||||

| (Ky, Rugemintwari, and Sauviat 2024) | √ | √ | [115] | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albuainain, A.; Ashby, S. Enablers and Barriers in FinTech Adoption: A Systematic Literature Review of Customer Adoption and Its Impact on Bank Performance. FinTech 2025, 4, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech4030049

Albuainain A, Ashby S. Enablers and Barriers in FinTech Adoption: A Systematic Literature Review of Customer Adoption and Its Impact on Bank Performance. FinTech. 2025; 4(3):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech4030049

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbuainain, Amna, and Simon Ashby. 2025. "Enablers and Barriers in FinTech Adoption: A Systematic Literature Review of Customer Adoption and Its Impact on Bank Performance" FinTech 4, no. 3: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech4030049

APA StyleAlbuainain, A., & Ashby, S. (2025). Enablers and Barriers in FinTech Adoption: A Systematic Literature Review of Customer Adoption and Its Impact on Bank Performance. FinTech, 4(3), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech4030049