Assessment of Brazilian Type F Fly Ash: Influence of Chemical Composition and Particle Size on Alkali-Activated Materials Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Reactivity of the raw material, dictated by amorphous phase content, particle size distribution, and mineralogy.

- Type and concentration of the alkali activator (e.g., NaOH, KOH, sodium silicate), which influence dissolution kinetics and gel polymerization [14].

- Curing conditions, such as temperature, humidity, and time, which can accelerate or hinder reaction products’ crystallinity and densification [15].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Fly Ash (FA)

2.1.2. Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH)

2.2. Experimental Program

2.3. Characterization of Precursor Materials and Alkali-Activated Pastes

3. Results

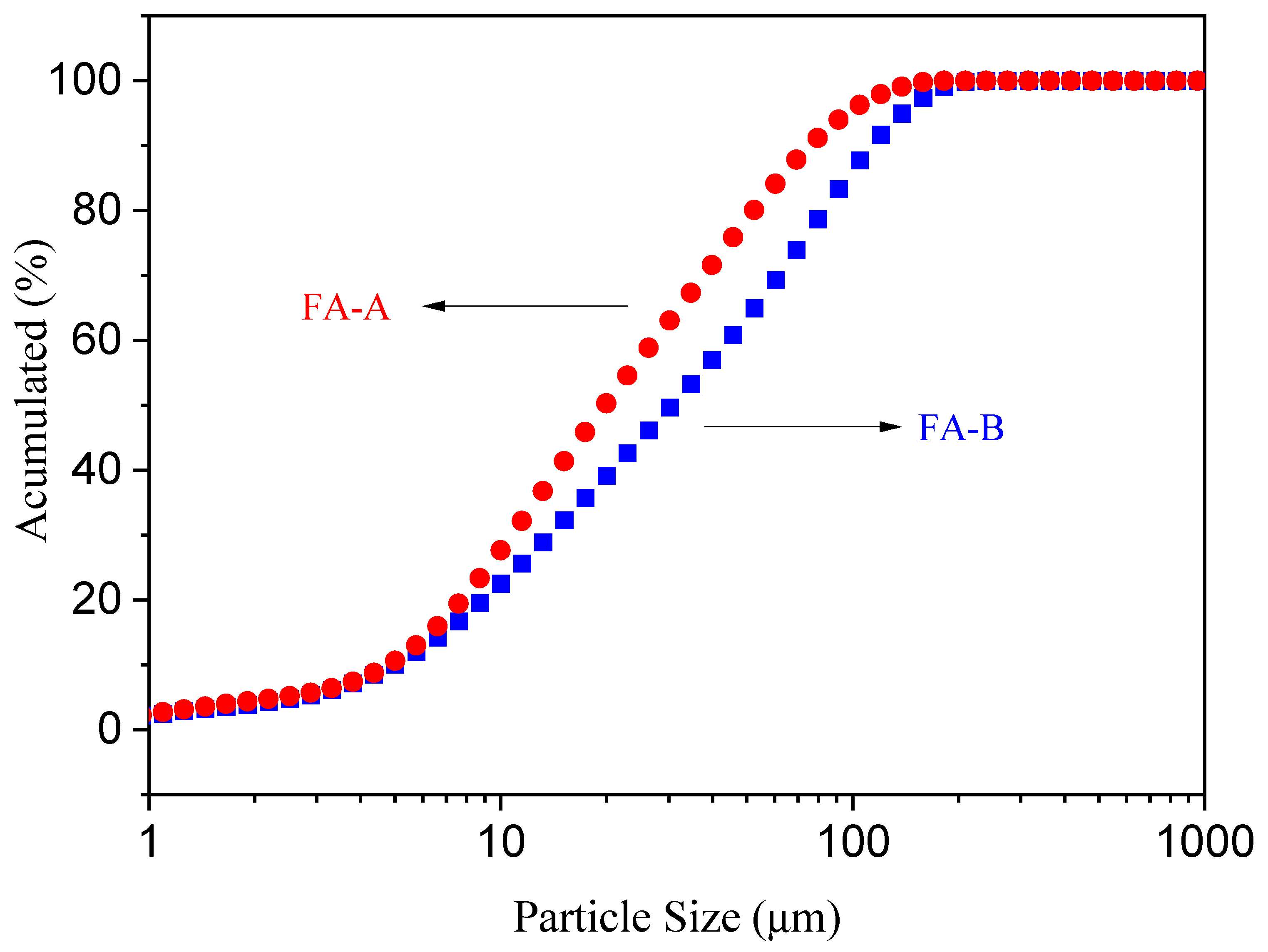

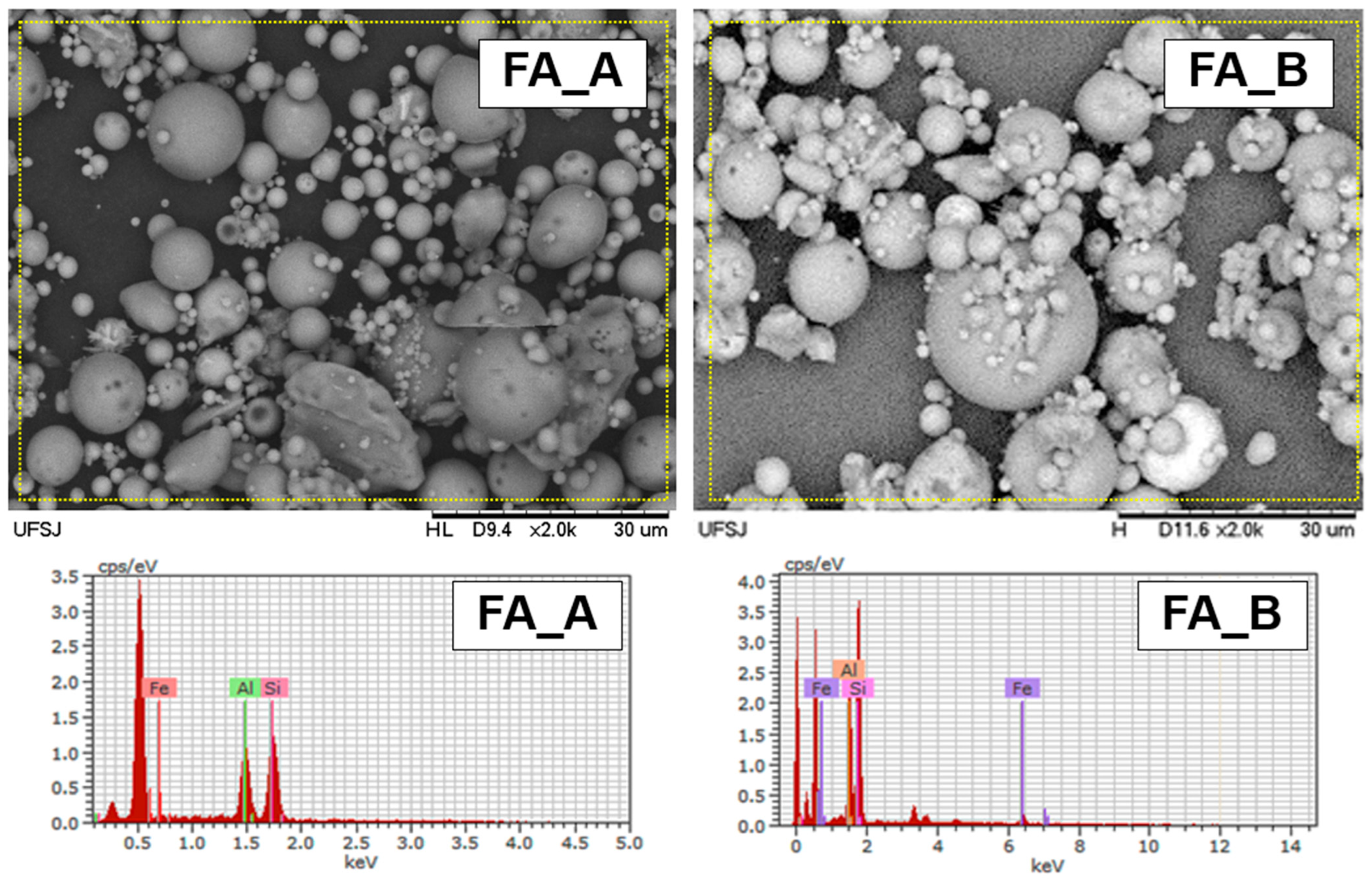

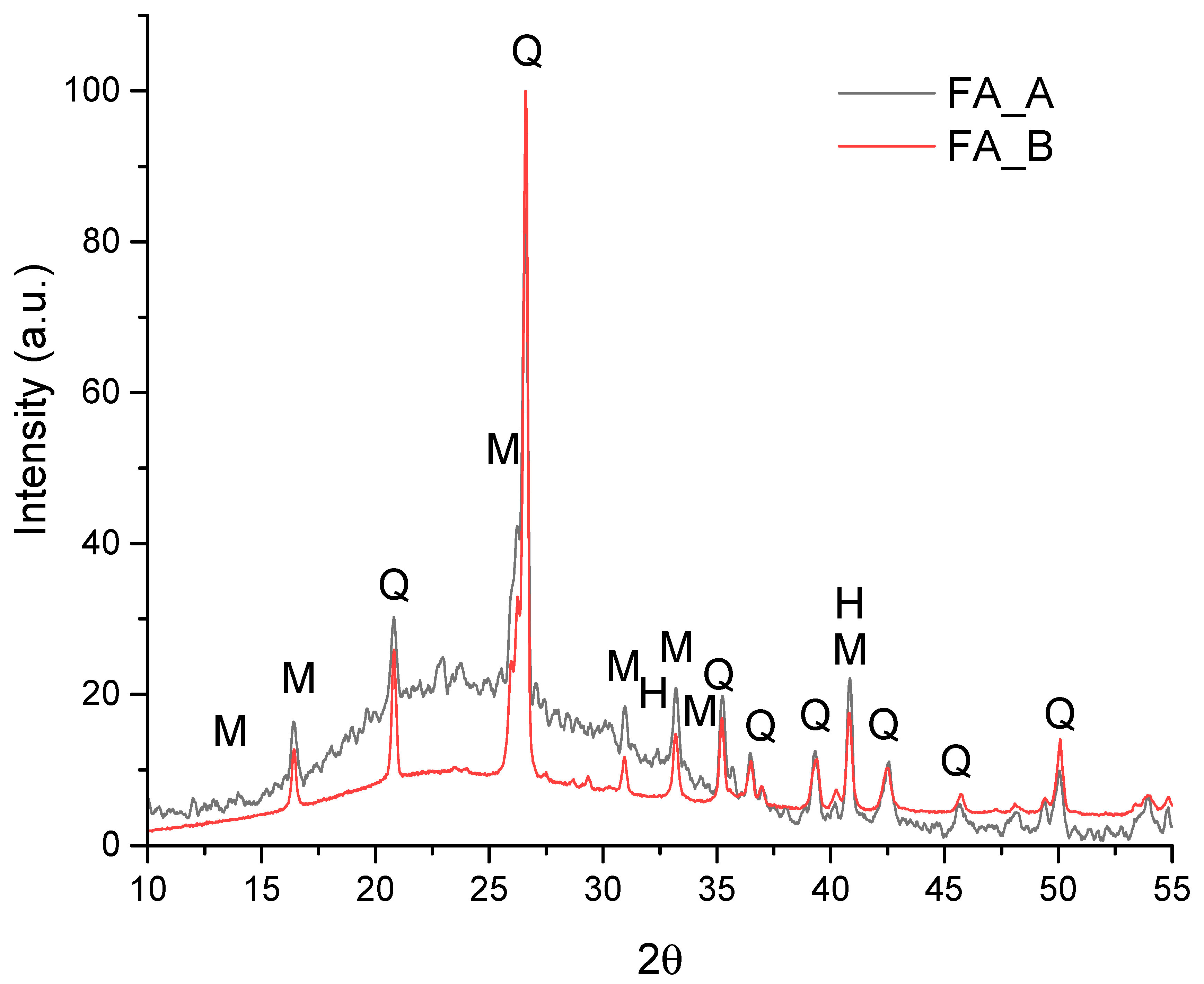

3.1. Characterization of FA Samples

3.2. Characterization of the Alkali-Activated Materials

3.2.1. Water Absorption, Porosity, and Density

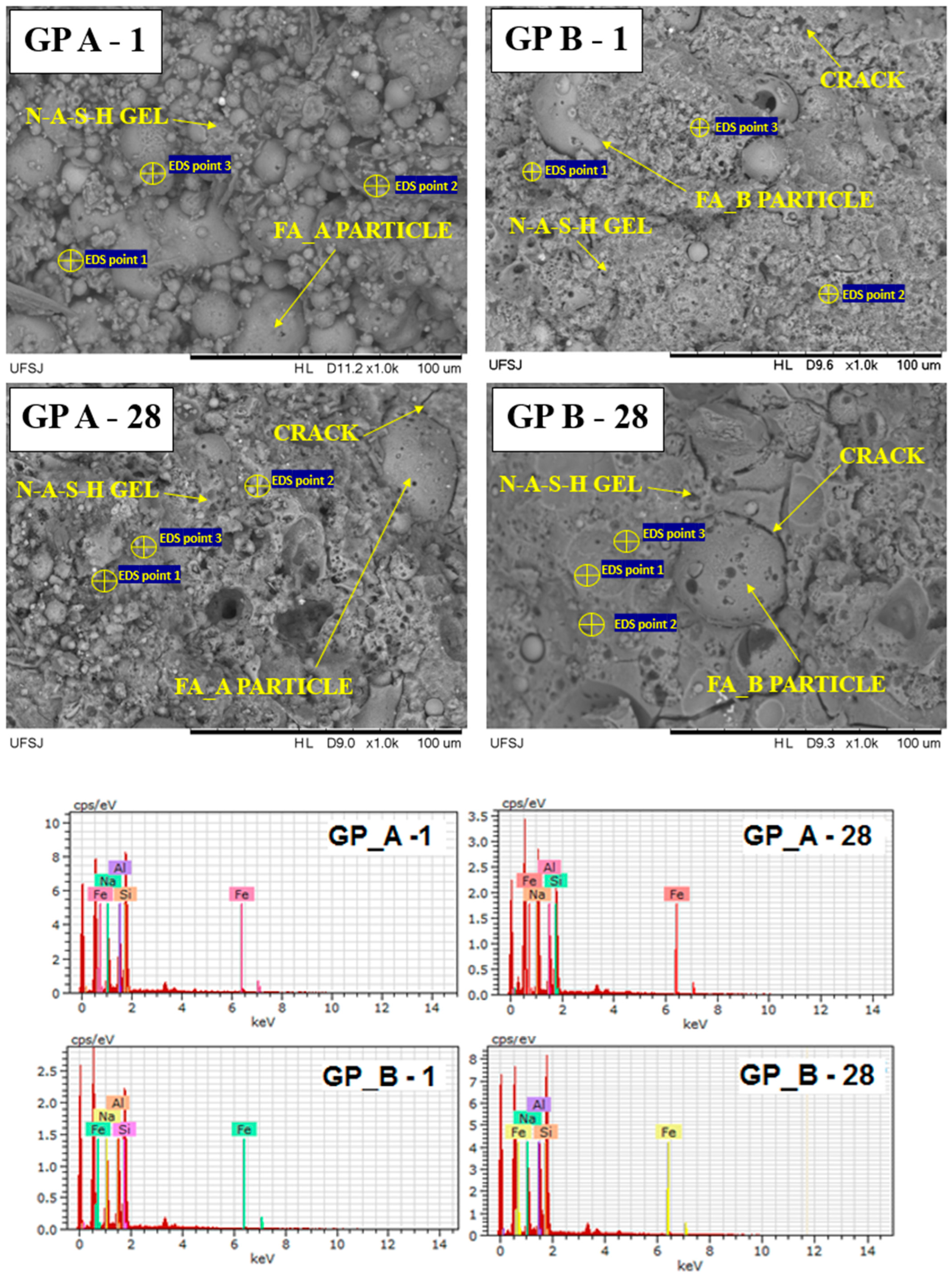

3.2.2. Microstructural Analysis

3.2.3. Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

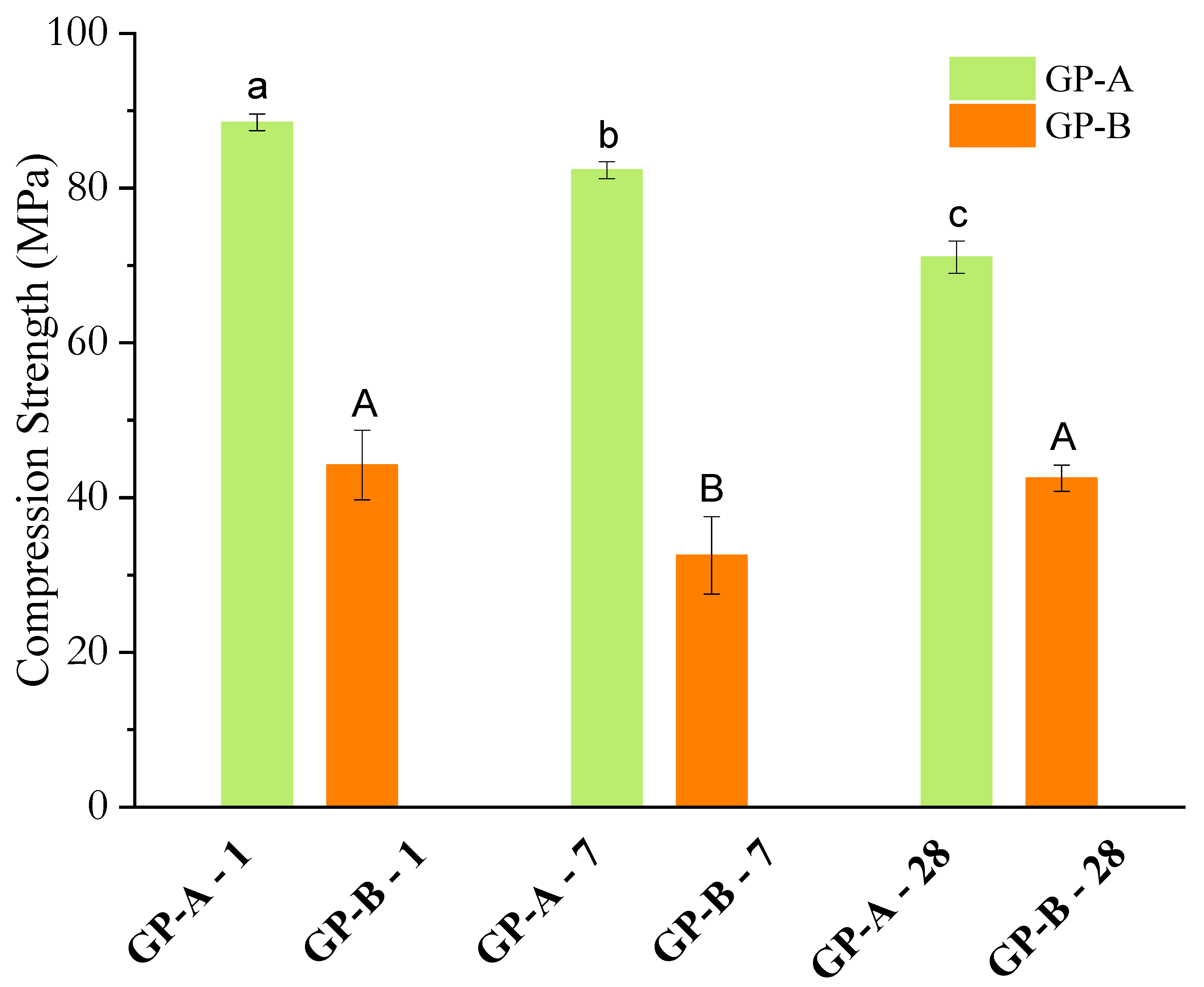

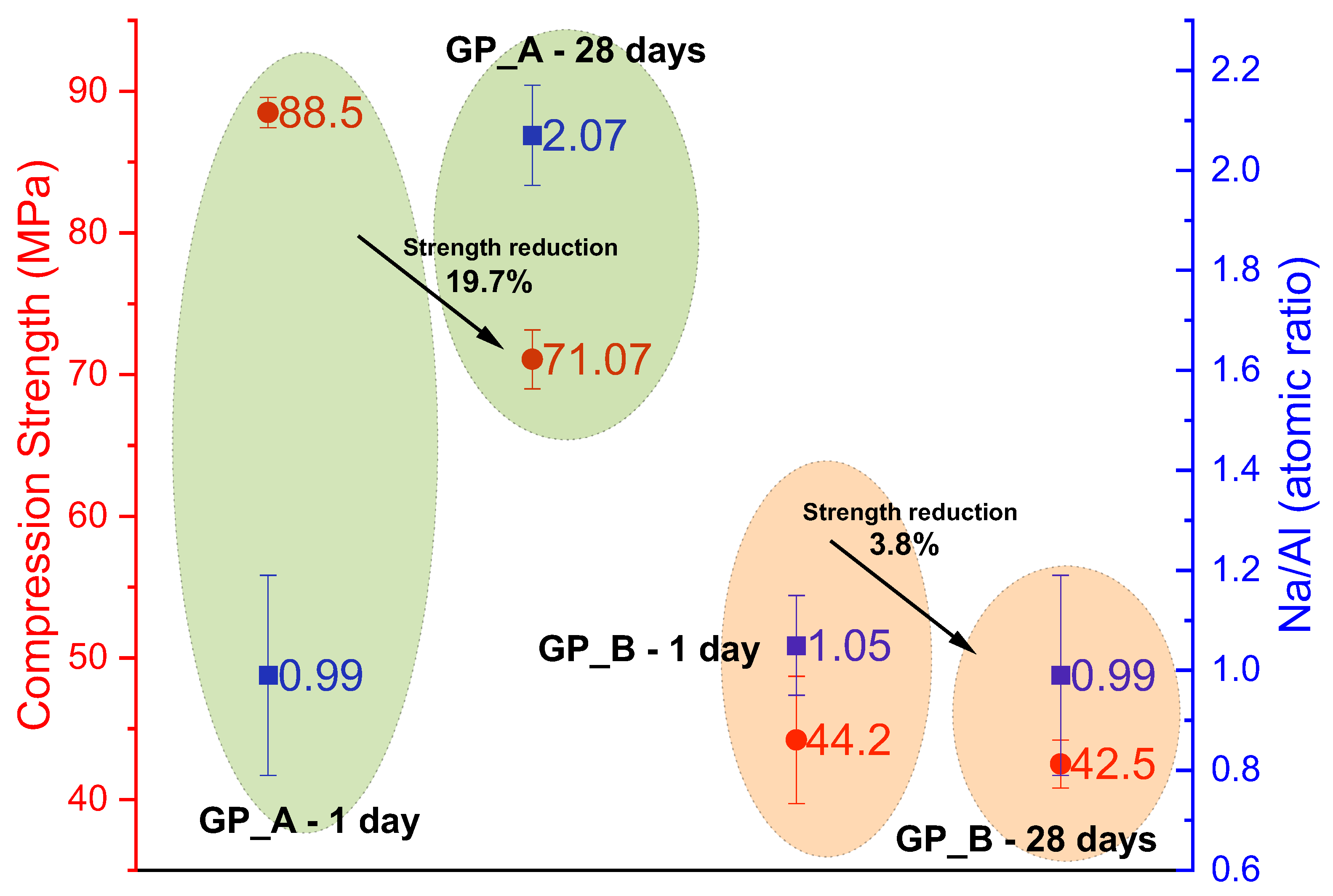

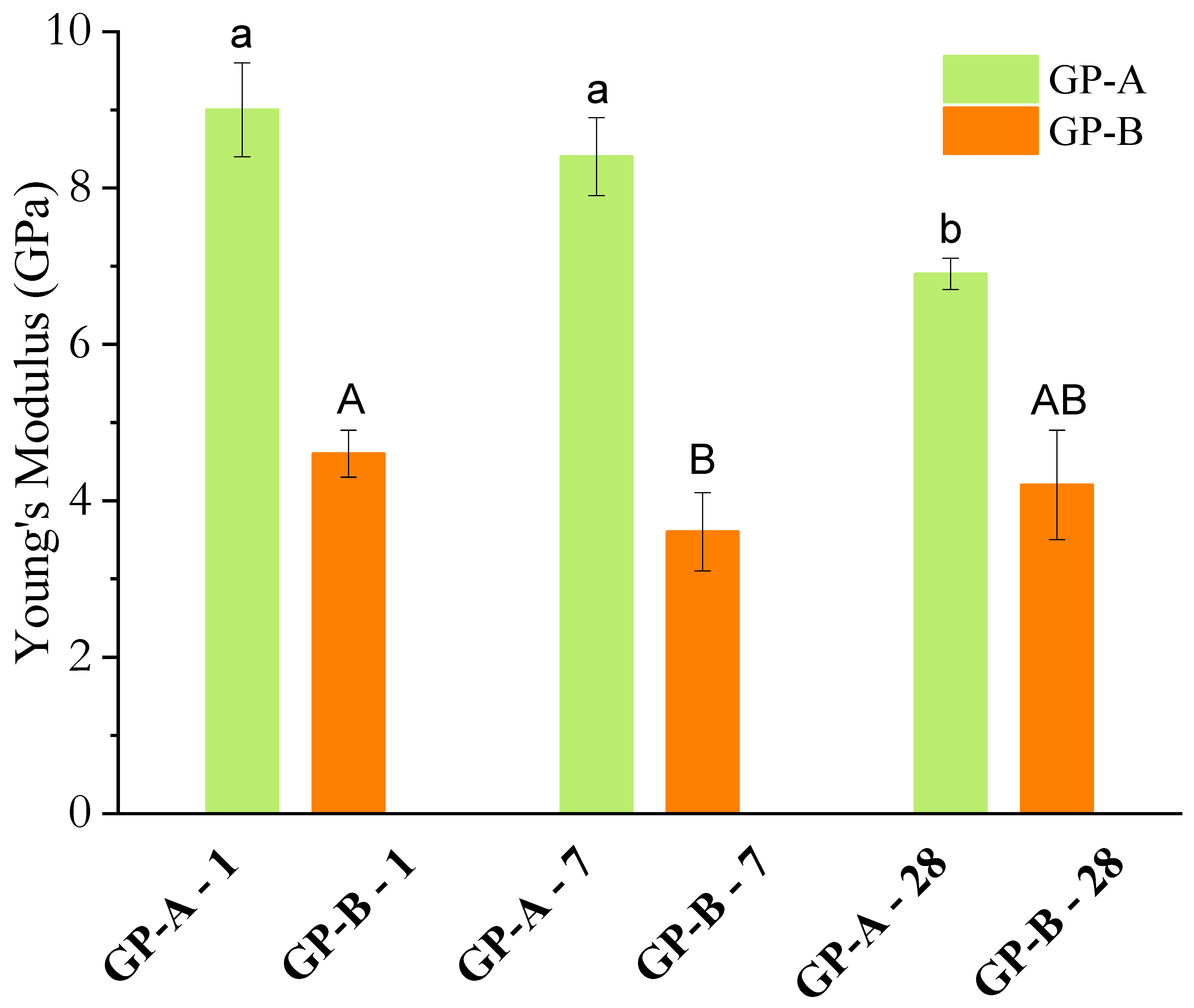

3.2.4. Compressive Strength and Young’s Modulus

| System/Material | Binder/Activator | Curing Regime | fc, 1 d (MPa) | fc, 7 d (MPa) | fc, 28 d (MPa) | Notes/Benchmark Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study—GP-A (FA-A) | FA (Type F)/16 M NaOH | 90 °C/24 h + RT | 88.5 | 82.3 | 71.1 | Very high early strength; 19% drop to 28 d due to excess alkali. |

| This study—GP-B (FA-B) | FA (Type F)/16 M NaOH | 90 °C/24 h + RT | 44.2 | 32.5 | 42.5 | Lower early strength; stable with only 3.8% drop to 28 d. |

| OPC mortar (CEM I 42.5N) * | Portland cement | RT, water cure | ~10 | ~35 | ≥42.5 | Strength class threshold (EN 197-1). |

| OPC mortar (CEM I 52.5N) * | Portland cement | RT, water cure | ~20 | ~45 | ≥52.5 | Higher class threshold (EN 197-1). |

| FA-based AAM (literature range) ** | FA/NaOH or Na2SiO3–NaOH | Ambient/mild heat | ~20 | ~40 | ~60 | Typical values reported: 40–90 MPa (28 d). |

| Slag-based AAM (literature range) ** | GGBFS/NaOH or Na2SiO3 | Ambient | ~40 | ~70 | ~90 | Fast strength gain; often 60–120 MPa (28 d). |

| High-performance concrete (HPC) | OPC + admixtures | Optimized curing | ~30 | ~60 | ~100 | Reference for structural applications ≥ 80–100 MPa (28 d). |

- Disruption of the aluminosilicate network through charge imbalance, reducing crosslink density;

- Promotion of microcracking due to carbonation of excess Na+, with associated volumetric changes;

- Leaching of soluble alkali phases, which can create micro voids and further weaken the matrix.

4. Conclusions

- Early-age strength: FA-A-based matrices achieved compressive strength of 88.5 MPa after 1 day, approximately 100% higher than FA-B (44.2 MPa). This behavior is linked to the higher SiO2/Al2O3 ratio (3.52) and the amorphous halo observed between 10–35° (2θ) in the XRD pattern, indicating greater availability of reactive aluminosilicates;

- Elastic modulus correlation: The higher compressive strength of FA-A was consistent with a higher elastic modulus (9.0 GPa vs. 4.6 GPa for FA-B), confirming the formation of a denser and stiffer matrix;

- Strength evolution: Over 28 days, FA-A exhibited a 19% reduction in compressive strength, associated with an increase in the Na/Al ratio (0.99 to 2.07) and the formation of Na2CO3 detected by FTIR. FA-B showed only a 3.8% decrease, maintaining a stable Na/Al ratio (~1.0) and thus better long-term stability;

- Microstructural differences: SEM analyses revealed that FA-A matrices were more homogeneous, with fewer unreacted particles and higher N–A–S–H gel formation, whereas FA-B retained partially unreacted spheres even after 28 days of curing;

- Physical properties: FA-B matrices exhibited lower water absorption (up to 52% lower after 7 days) and slightly higher density (1.8 g·cm−3) compared to FA-A, suggesting improved long-term densification;

- Chemical analysis: EDS results indicated that FA-A mainly formed poly(sialate-siloxy) networks, while FA-B presented a combination of poly(sialate-siloxy) and poly(sialate-disiloxy), influencing gel connectivity and durability.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azevedo, A.G.S.; Strecker, K. Kaolin, Fly-Ash and Ceramic Waste Based Alkali-Activated Materials Production by the “One-Part” Method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjewar, B.A.; Chippagiri, R.; Dakwale, V.A.; Ralegaonkar, R.V. Application of Alkali-Activated Sustainable Materials: A Step Towards Net Zero Binder. Energies 2023, 16, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qader, D.N.; Jamil, A.S.; Bahrami, A.; Ali, M.; Arunachalam, K.P. A Systematic Review of Metakaolin-Based Alkali-Activated and Geopolymer Concrete: A Step Toward Green Concrete. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2025, 64, 20240076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Azevedo, A.G.; Strecker, K. Brazilian Fly Ash Based Inorganic Polymers Production Using Different Alkali Activator Solutions. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 9012–9018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J.; Comrie, D. Long Term Durability of Hazardous Toxic and Nuclear Waste Disposals. Proc. Geopolymer 1988, 1, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Provis, J.L.; Bernal, S.A. Geopolymers and Related Alkali-Activated Materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2014, 44, 299–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yu, H.; Gong, W.; Liu, T.; Wang, N.; Tan, Y.; Wu, C. Effects of Low- and High-Calcium Fly Ash on the Water Resistance of Magnesium Oxysulfate Cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 230, 116951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jia, Z.; Qi, X.; Wang, W.; Guo, S. Alkali-Activated Materials Without Commercial Activators: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 3780–3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutsos, M.; Boyle, A.P.; Vinai, R.; Hadjierakleous, A.; Barnett, S.J. Factors Influencing the Compressive Strength of Fly Ash Based Geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 110, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Part, W.K.; Ramli, M.; Cheah, C.B. An Overview on the Influence of Various Factors on the Properties of Geopolymer Concrete Derived from Industrial By-Products. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 77, 370–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Palomo, Á. Composition and Microstructure of Alkali Activated Fly Ash Binder: Effect of the Activator. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; El-Korchi, T.; Zhang, G.; Liang, J.; Tao, M. Synthesis Factors Affecting Mechanical Properties, Microstructure, and Chemical Composition of Red Mud-Fly Ash Based Geopolymers. Fuel 2014, 134, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andini, S.; Cioffi, R.; Colangelo, F.; Grieco, T.; Montagnaro, F.; Santoro, L. Coal Fly Ash as Raw Material for the Manufacture of Geopolymer-Based Products. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, G. The Strength and Microstructure of Two Geopolymers Derived from Metakaolin and Red Mud-Fly Ash Admixture: A Comparative Study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 30, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahromy, S.S.; Azam, M.; Huber, F.; Jordan, C.; Wesenauer, F.; Huber, C.; Naghdi, S.; Schwendtner, K.; Neuwirth, E.; Laminger, T.; et al. Comparing Fly Ash Samples from Different Types of Incinerators for Their Potential as Storage Materials for Thermochemical Energy and CO2. Materials 2019, 12, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horan, C.; Genedy, M.; Juenger, M.; van Oort, E. Fly Ash-Based Geopolymers as Lower Carbon Footprint Alternatives to Portland Cement for Well Cementing Applications. Energies 2022, 15, 8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamsashree; Pandit, P.; Prashanth, S.; Katpady, D.N. Durability of Alkali-Activated Fly Ash-Slag Concrete- State of Art. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraco, M.N.S.; Simão, L.; Acordi, J.; Olivo, E.F.; Zaccaron, A.; Montedo, O.R.K.; Ribeiro, M.J.; Bergmann, C.P.; Raupp-Pereira, F. An Overview of the Coal Circularity in Brazil: A New Sustainable Approach Based on Sampling Method, Characterization, and Waste Valorization. Resour. Policy 2025, 102, 105496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.G.S.; Strecker, K.; Barros, L.A.; Tonholo, L.F.; Lombardi, C.T. Effect of Curing Temperature, Activator Solution Composition and Particle Size in Brazilian Fly-Ash Based Geopolymer Production. Mater. Res. 2019, 22, e20180842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO EN, 10545-3EN; Ceramic Tiles—Part 3: Determination of Water Absorption, Apparent Porosity, Apparent Relative Density and Bulk Density. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- ABNT NBR—5739; Concreto—Ensaio de Compressão de Corpos-de-Prova Cilíndricos. Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2007.

- Görhan, G.; Kürklü, G. The Influence of the NaOH Solution on the Properties of the Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Mortar Cured at Different Temperatures. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 58, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618-15; Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Somna, K.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Kajitvichyanukul, P.; Chindaprasirt, P. NaOH-Activated Ground Fly Ash Geopolymer Cured at Ambient Temperature. Fuel 2011, 90, 2118–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; Palomo, A.; van Deventer, J.S. Geopolymer Technology: The Current State of the Art. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 42, 2917–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalchuk, G.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Palomo, A. Alkali-Activated Fly Ash: Effect of Thermal Curing Conditions on Mechanical and Microstructural Development—Part II. Fuel 2007, 86, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, A.; Grutzeck, M.W.; Blanco, M.T. Alkali-Activated Fly Ashes: A Cement for the Future. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Palomo, A. Mid-Infrared Spectroscopic Studies of Alkali-Activated Fly Ash Structure. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 86, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temuujin, J.; Minjigmaa, A.; Davaabal, B.; Bayarzul, U.; Ankhtuya, A.; Jadambaa, T.; MacKenzie, K.J.D. Utilization of Radioactive High-Calcium Mongolian Flyash for the Preparation of Alkali-Activated Geopolymers for Safe Use as Construction Materials. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 16475–16483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozgawa, W.; Deja, J. Spectroscopic Studies of Alkaline Activated Slag Geopolymers. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 924, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.F.A.; Chen, B.; Oderji, S.Y.; Haque, M.A.; Ahmad, M.R. Improvement of Early Strength of Fly Ash-Slag Based One-Part Alkali Activated Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 246, 118533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 197-1; Cement—Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Azevedo, A.D.S.; Strecker, K.; Lombardi, C.T. Produção de Geopolímeros à Base de Metacaulim e Cerâmica Vermelha. Cerâmica 2018, 64, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemougna, P.N.; MacKenzie, K.J.D.; Jameson, G.N.L.; Rahier, H.; Chinje Melo, U.F. The Role of Iron in the Formation of Inorganic Polymers (Geopolymers) from Volcanic Ash: A 57Fe Mössbauer Spectroscopy Study. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 5280–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peys, A.; White, C.E.; Rahier, H.; Blanpain, B.; Pontikes, Y. Alkali-Activation of CaO-FeOX-SiO2 Slag: Formation Mechanism from in-Situ X-Ray Total Scattering. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 122, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.; Gluth, G.J.G.; Peys, A.; Onisei, S.; Banerjee, D.; Pontikes, Y. The Fate of Iron During the Alkali-Activation of Synthetic (CaO-)FeOX-SiO2 Slags: An Fe K-Edge XANES Study. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 101, 2107–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. Alkali-Activated Materials: State-of-Art Report; Springer: Melbourne, Australia, 2014; ISBN 9789400776715. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Palomo, A.; Criado, M. Microstructure Development of Alkali-Activated Fly Ash Cement: A Descriptive Model. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | D10 | D50 | D90 | Specific Mass (g/cm3) | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (µm) | (µm) | (µm) | |||

| FA-A | 4.81 | 19.70 | 75.44 | 2.38 | 1.3 |

| FA-B | 4.97 | 30.82 | 112.87 | 2.21 | 0.9 |

| Sample | SiO2 (wt.%) | Al2O3 (wt.%) | Fe2O3 (wt.%) | CaO (wt.%) | Other Oxides * (wt.%) | SiO2/Al2O3 ** | LOI *** (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA-A | 61.025 | 29.406 | 6.155 | 0.65 | 2.764 | 3.52 | 1.87 |

| FA-B | 61.546 | 31.234 | 3.884 | 0.98 | 2.356 | 3.34 | 2.23 |

| Element | [at. %] | |

|---|---|---|

| FA-A | Si | 72.09 |

| Al | 25.50 | |

| Fe | 2.41 | |

| FA-B | Si | 66.56 |

| Al | 29.62 | |

| Fe | 3.82 |

| Sample | Water Absorption (%) | Apparent Porosity (%) | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP-A-1 | 13.2 ± 0.5 a | 21.1 ± 0.9 a | 1.6 ± 0.1 a |

| GP-A-7 | 13.5 ± 0.5 a | 20.7 ± 0.7 a | 1.6 ± 0.1 a |

| GP-A-28 | 12.4 ± 0.1 b | 20.0 ± 0.2 a | 1.6 ± 0.2 a |

| GP-B-1 | 12.3 ± 0.4 A | 20.6± 0.5 A | 1.7± 0.1 A |

| GP-B-7 | 6.4 ± 0.5 C | 19.2 ± 0.5 B | 1.8 ± 0.1 A |

| GP-B-28 | 9.7 ± 0.3 B | 20.2 ± 1.5 AB | 1.7 ± 0.2 A |

| Sample— Curing Time (Days) | Element | [at. %] | Si/Al (Atomic Ratio) | Na/Al (Atomic Ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP-A–1 | Si | 49.77 ± 0.1 | 2.02 ± 0.2 | 0.99 ± 0.2 |

| Al | 24.61 ± 0.2 | |||

| Na | 24.30 ± 0.2 | |||

| Fe | 1.32 ± 0.4 | |||

| GP-A–28 | Si | 38.97 ± 0.2 | 2.01 ± 0.2 | 2.07 ± 0.1 |

| Al | 19.37 ± 0.4 | |||

| Na | 40.24 ± 0.5 | |||

| Fe | 1.43 ± 0.4 | |||

| GP-B–1 | Si | 52.76 ± 0.1 | 2.47 ± 0.1 | 1.05 ± 0.1 |

| Al | 21.39 ± 0.5 | |||

| Na | 22.42 ± 0.2 | |||

| Fe | 3.43 ± 0.1 | |||

| GP-B–28 | Si | 55.57 ± 0.1 | 2.62 ± 0.2 | 0.99 ± 0.2 |

| Al | 21.18 ± 0.1 | |||

| Na | 21.17 ± 0.5 | |||

| Fe | 2.08 ± 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azevedo, A.G.S. Assessment of Brazilian Type F Fly Ash: Influence of Chemical Composition and Particle Size on Alkali-Activated Materials Properties. Powders 2026, 5, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/powders5010002

Azevedo AGS. Assessment of Brazilian Type F Fly Ash: Influence of Chemical Composition and Particle Size on Alkali-Activated Materials Properties. Powders. 2026; 5(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/powders5010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzevedo, Adriano G. S. 2026. "Assessment of Brazilian Type F Fly Ash: Influence of Chemical Composition and Particle Size on Alkali-Activated Materials Properties" Powders 5, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/powders5010002

APA StyleAzevedo, A. G. S. (2026). Assessment of Brazilian Type F Fly Ash: Influence of Chemical Composition and Particle Size on Alkali-Activated Materials Properties. Powders, 5(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/powders5010002