Practice What You Teach: Preschool Educators’ Dietary Behaviors and BMI †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

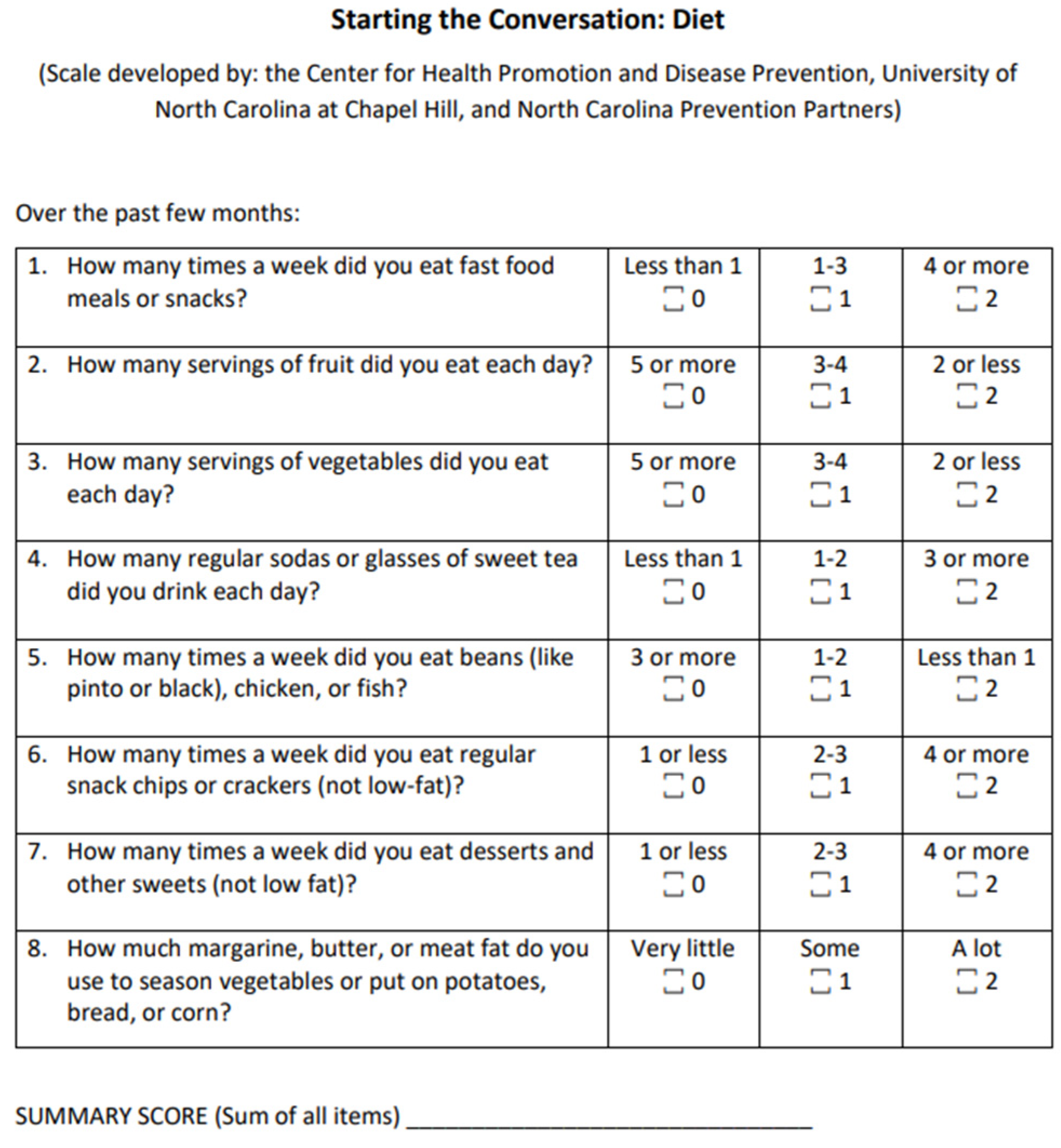

2.2. Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control |

| HHS | Health and Human Services |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| CACFP | Child and Adult Care Feeding Program |

| I-POP | Impact of a Preschool Obesity Prevention |

| SSB | Sugar Sweetened Beverages |

| STC | Starting the Conversation |

| NCI | National Cancer Institute |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood Obesity Facts. 17 May 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood-obesity-facts/childhood-obesity-facts.html (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Chen, C.Y.; Kao, C.C.; Hsu, H.Y.; Wang, R.H.; Hsu, S.H. The efficacy of a family-based intervention program on childhood obesity: A quasi-experimental design. Bio Res. Nurs. 2015, 17, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, E.S.; Clifford, L.M.; Stark, L.J. Obesity in preschoolers: Behavioral correlates and directions for treatment. Obesity 2012, 20, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messiah, S.E.; Vidot, D.C.; Gurnurkar, S.; Alhezayen, R.; Natale, R.A.; Arheart, K.L. Obesity is significantly associated with cardiovascular disease risk factors in 2- to 9-year-olds. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2014, 16, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Grieken, A.; Renders, C.M.; Wijtzes, A.I.; Hirasing, R.A.; Raat, H. Overweight, obesity, and underweight is associated with adverse psychosocial and physical health outcomes among 7-year-old children: The “Be Active, Eat Right” Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.S.; Mulder, C.; Twisk, J.W.R.; van Mechelen, W.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: A systematic review of literature. Obes. Rev. 2012, 9, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, M.; Clifford, S.; Patton, G.; Waters, E.; Williams, J.; Canterford, L.; Carlin, J.B. Morbidity patterns among the underweight, overweight and obese between 2 and 18 years: Population-based cross-sectional analyses. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Education Sciences; National Center for Education Statistics. Fast Facts: Preprimary Education Enrollment. 2025. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=516 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Head Start Program Performance Standards. December 2016. Available online: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/hspps-final.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Gubbels, J.S.; Gerards, S.M.P.L.; Kremers, S.P.J. Use of food practices by childcare staff and the association with dietary intake of children at childcare. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2161–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.; Blanger, M.; Donovan, D.; Vatanparast, H.; Muhajarine, N.; Engler-Stringer, R.; Leis, A.; Humbert, M.L.; Carrier, N. Association between childcare educators’ practices and preschoolers’ physical activity and dietary intake: A cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/policy/45-cfr-chap-xiii (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Ling, J. Behavioral and psychosocial characteristics among Head Start childcare providers. J. Sch. Nurs. 2017, 34, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolden, C.; Huye, H.; Paprzycki, P. Practice what you teach: Implications for teachers modeling healthy eating behaviors. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, A23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huye, H.F.; Connell, C.L.; Dufrene, B.A.; Mohn, R.S.; Caroline, N.; Tannehill, J.; Sutton, V. Development of the Impact of a Preschool Obesity Prevention (I-POP) intervention enhanced with positive behavioral supports for Mississippi Head Start centers. J. Nutr. Educ. 2020, 52, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, A.E.; Strycker, L.A.; Toobert, D.J.; Ammerman, A.S.; Glasgow, R.E. Starting the conversation performance of a brief dietary assessment and intervention tool for health professionals. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.K.; Chang, V.W. Weight status and restaurant availability: A multilevel analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.V.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Nettleton, J.A.; Jacobs, D.R.; Franco, M. Fast-food consumption, diet quality, and neighborhood exposure to fast food. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 170, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczek-Rubińska, A.; Bajerska, J. The consumption of energy dense snacks and some contextual factors of snacking may contribute to higher energy intake and body weight in adults. Nutr. Res. 2021, 96, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garza, K.B.; Ding, M.; Owensby, J.K.; Zizza, C.A. Impulsivity and Fast-Food Consumption: A Cross-Sectional Study among Working Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, V.S.; Pan, A.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelli, M.N.; Schoeller, D.A. Traditional self-reported dietary instruments are prone to inaccuracies and new approaches are needed. Front. Nutr. 2021, 3, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, M.K.; Nigg, C.R.; Fialkowski, M.K.; Braun, K.L.; Li, F.; Novotny, R. Influence of teachers’ personal health behaviors on operationalizing obesity prevention policy in Head Start preschools: A project of the Children’s Healthy Living Program (CHL). J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandia, G.; Vaughn, A.E.; Bateman, L.A.; Ward, D.S.; Linnan, L.A. Development of a workplace intervention for child care staff: Caring and Reaching for Health’s (CARE) Healthy Lifestyles Intervention. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubani Husseini, M.; Zwas, D.R.; Donchin, M. Teacher training and engagement in health promotion mediates health behavior outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Teachers | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 64 | 98.5 |

| Male | 1 | 1.5 |

| Staff Status | ||

| Teacher | 29 | 44.6 |

| Teacher Assistant | 24 | 36.9 |

| Missing | 12 | 18.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Black or African American | 61 | 93.8 |

| White | 2 | 3.1 |

| Other | 2 | 3 |

| Language other than English at home | ||

| No | 64 | 98.5 |

| Yes | 1 | 1.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 18 | 27.7 |

| Now married | 32 | 49.2 |

| Separated or divorced | 11 | 17 |

| Widowed | 3 | 4.6 |

| Missing | 1 | 1 |

| Education completed | ||

| Some College | 6 | 9.2 |

| College Degree | 46 | 70.8 |

| Some Graduate | 3 | 4.6 |

| Graduate Degree | 10 | 15.4 |

| Income | ||

| <$5000 | 3 | 4.6 |

| $5000–$9999 | 5 | 7.7 |

| $10,000–$14,999 | 13 | 20 |

| $15,000–$19,999 | 12 | 18.5 |

| $20,000–$24,999 | 7 | 10.8 |

| $25,000–$29,999 | 1 | 2.3 |

| >$30,000 | 9 | 13.8 |

| Not disclosed | 7 | 10 |

| Missing | 8 | 12.3 |

| Measure | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| - | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.22 | −0.13 | 0.37 ** | 0.31 * | 0.21 | 0.27 * |

| 0.13 | - | 0.40 ** | −0.05 | −0.18 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| 0.18 | 0.40 ** | - | −0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.11 |

| 0.22 | −0.05 | 0.09 | - | 0.02 | 0.48 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.24 |

| −0.13 | −0.18 | 0.10 | 0.02 | - | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.18 |

| 0.37 ** | −0.00 | 0.08 | 0.48 ** | −0.02 | - | 0.44 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.33 ** |

| 0.31 * | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.38 ** | 0.02 | 0.44 ** | - | 0.33 ** | 0.22 |

| 0.21 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.33 ** | 0.07 | 0.29 * | 0.33 * | - | −0.09 |

| 0.27 * | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.33 ** | 0.22 | −0.09 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Landry, A.S.; Bolden, C.F.; Babin, M.; Huye, H. Practice What You Teach: Preschool Educators’ Dietary Behaviors and BMI. Dietetics 2026, 5, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics5010002

Landry AS, Bolden CF, Babin M, Huye H. Practice What You Teach: Preschool Educators’ Dietary Behaviors and BMI. Dietetics. 2026; 5(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics5010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleLandry, Alicia S., Candace F. Bolden, Mercedes Babin, and Holly Huye. 2026. "Practice What You Teach: Preschool Educators’ Dietary Behaviors and BMI" Dietetics 5, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics5010002

APA StyleLandry, A. S., Bolden, C. F., Babin, M., & Huye, H. (2026). Practice What You Teach: Preschool Educators’ Dietary Behaviors and BMI. Dietetics, 5(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics5010002