Study of Influencing Factors in Consumer Attitude, Consumption, and Purchasing Frequency in the Market of Flour and Bakery Products in Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

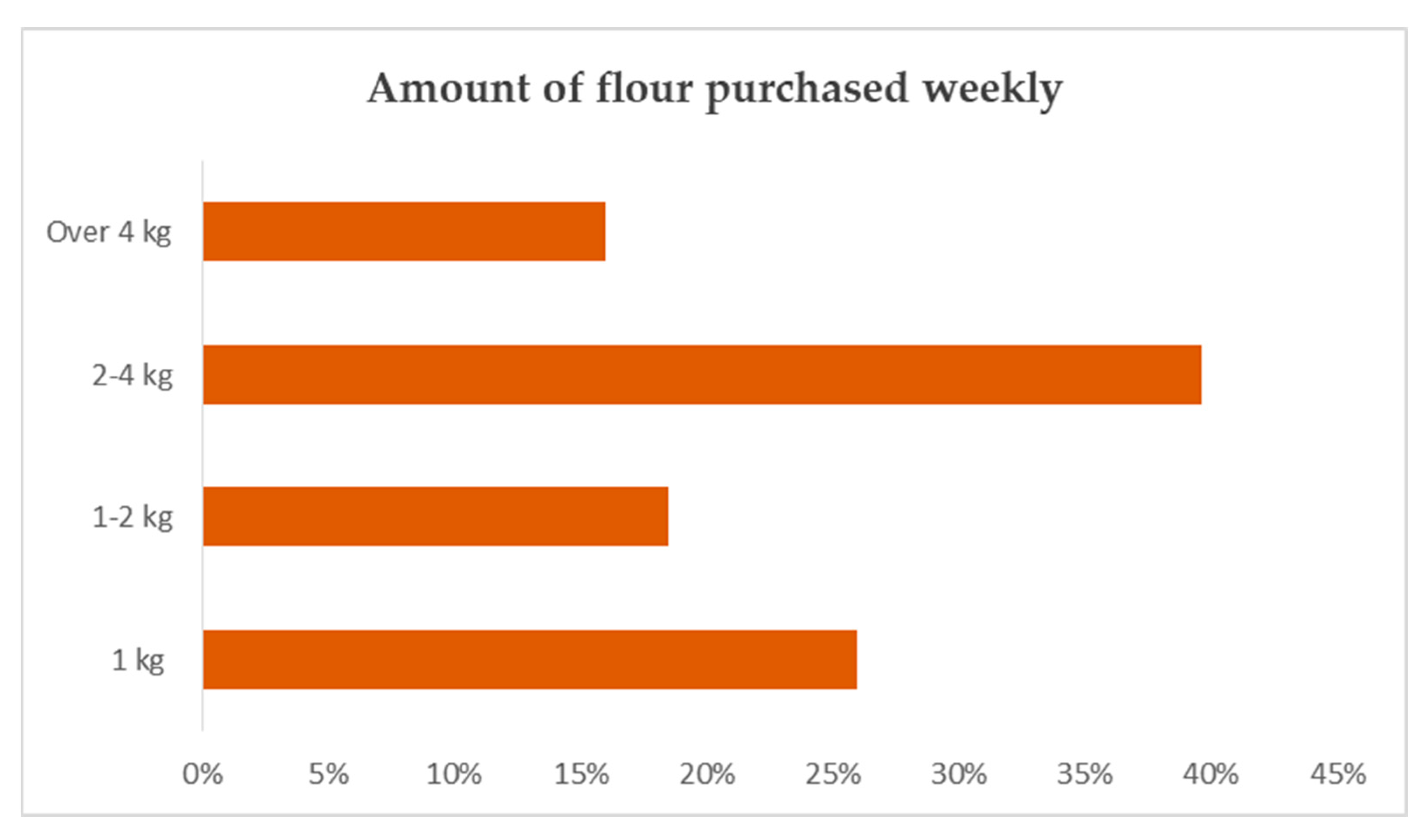

3.2. Participants’ Data on Flour Purchase

3.3. Participants’ Data on Preferences and Attitudes Towards Bakery Products’, Purchase Frequencies, and Consumption

3.4. Participants’ Attitude Towards Innovative Functional Food Products

3.5. Results of the First Hypothesis (H1)

3.5.1. How Demographic Characteristics Influenced the Use of Flour Purchased by Consumers

3.5.2. How Demographic Characteristics Affected the Type of Flour Consumers Buy

3.5.3. How Demographic Characteristics Affected Consumers’ Purchase Factor of Flour

3.5.4. How Demographic Characteristics Affect the Weekly Amount of Flour Consumers Buy

3.6. Results of the Second Hypothesis (H2)

3.6.1. How Demographic Characteristics Affect the Frequency of Bakery Consumption

3.6.2. How Demographic Characteristics Influence the Type of Bakery Usually Consumed

3.6.3. How Demographic Characteristics Affect Bakery Products Purchase Frequency

3.6.4. How Demographic Characteristics Influence Consumers’ Opinion on Whether Bakery Products Have Nutritional Value

3.6.5. How Demographic Characteristics Influence Consumers’ Opinions on Whether Bakery Products Are Good for Our Health

3.6.6. How Demographic Characteristics Influence Consumers’ Opinions on Bakery Products

3.7. Results of the Third Hypothesis (H3)

3.7.1. How Demographic Characteristics Influence Consumers’ Opinion of Whether They Always Want to Try New Innovative Food Products

3.7.2. How Demographic Characteristics Influence Consumer Trust in Innovative Food Products

3.7.3. How Demographic Characteristics Affect Consumers’ Knowledge of the Existence of Bakery Products from Alternative Flours

3.7.4. How Demographic Characteristics Influence Consumers’ Opinion on Whether They Would Try Bakery Products Made from Flours Alternatives to Wheat

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kubicová, Ľ.; Predanocyová, K. Situation in the Market of Bakery Products. In International Scientific Days 2018; Wolters Kluwer ČR: Prahgue, Czech, 2018; pp. 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Bread & Cereal Products-Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/bread-cereal-products/worldwide?srsltid=AfmBOoqm27bOYfZPD_0OMxFAnSsOd7bFRQp5nr5NXkexYnlVBeMFZKAf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Yefimenko, A.G.; Mitskevich, B. Economic assessment and forecast of the efficiency of food production. In Proceedings of the Strategic Priorities for the Development of the Economy and Its Information Support: Materials of the International Scientific Conference of Young Scientists and University Teachers, Kuban State Agricultural University, Krasnodar, Russia, 10 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Diplock, A.T.; Aggett, P.; Ashwell, M.; Bornet, F.R.J.; Fern, E.B.; Roberfroid, M.B. Scientific Concepts of Functional Foods in Europe Consensus Document. Br. J. Nutr. 1999, 81, S1–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, establishing the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food saf. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2002, 1–24.

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 9–25.

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of 16 December 2008 on food additives. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2008, 16–33.

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union Regulation (EC) No 915/2023 of the European Parliament and of the Council of of 25 April 2023 Establishing Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Food. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, 1–125.

- Mickiewicz, B.; Britchenko, I. Main trends and development forecast of bread and bakery products market. VUZF Rev. 2022, 7, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, A.; Laganà, V.R.; Di Gregorio, D. Habits, Health and Environment in the Purchase of Bakery Products: Consumption Preferences and Sustainable Inclinations before and during COVID-19. Foods 2023, 12, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Castro, I.; Vicente, A.; Bourbon, A.I.; Cerqueira, M.Â. Functional Bakery Products: An Overview and Future Perspectives. In Bakery Products Science and Technology, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 9781119967, pp. 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziki, D.; Różyło, R.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Świeca, M. Current trends in the enhancement of antioxidant activity of wheat bread by the addition of plant materials rich in phenolic compounds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 40, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, M.; Varshney, A.; Rai, M.; Chikara, A.; Pohty, A.L.; Joshi, A.; Binjola, A.; Singh, C.P.; Rawat, K.; Rather, M.A.; et al. A comprehensive review on nutraceutical potential of underutilized cereals and cereal-based products. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 12, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, Z.E.; Pinho, O.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O. Food industry by-products used as functional ingredients of bakery products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ktenioudaki, A.; Gallagher, E. Recent advances in the development of high-fibre baked products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 28, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, N.; Indrani, D. Functional Ingredients of Wheat-Based Bakery, Traditional, Pasta, and Other Food Products. Food Rev. Int. 2015, 31, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Bansal, S.; Mangal, M.; Dixit, A.K.; Gupta, R.K.; Mangal, A.K. Utilization of food processing by-products as dietary, functional, and novel fiber: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1647–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivam, A.S.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Quek, S.Y.; Perera, C.O. Properties of bread dough with added fiber polysaccharides and phenolic antioxidants: A review. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, R163–R174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitelut, A.; Popa, E.; Popescu, P.; Popa, M. Trends of innovation in bread and bakery production. In Trends in Wheat and Bread Making; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Semenova, E.; Semenov, A. Impact of Bakery Innovation on Business Resilience Growth. In Baking Business Sustainability Through Life Cycle Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 241–259. [Google Scholar]

- Vergari, F.; Tibuzzi, A.; Basile, G. An overview of the functional food market: From marketing issues and commercial players to future demand from life in space. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 698, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riso, P.; Soldati, L. Food ingredients and supplements: Is this the future? J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.T.; Lu, P.; Parrella, J.A.; Leggette, H.R. Investigating the Effect of Consumers’ Knowledge on Their Acceptance of Functional Foods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menrad, K. Market and marketing of functional food in Europe. J. Food Eng. 2003, 56, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Consumer acceptance of novel food technologies. Nat. food 2020, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Parmenter, K.; Waller, J. Nutrition knowledge and food intake. Appetite 2000, 34, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topolska, K.; Florkiewicz, A.; Filipiak-Florkiewicz, A. Functional Food-Consumer Motivations and Expectations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Vecchio, R. Functional foods development in the European market: A consumer perspective. J. Funct. Foods 2011, 3, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; West, G.E.; Wang, C. Consumer attitudes and acceptance of CLA-enriched dairy products. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 54, 663–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urala, N.; Lähteenmäki, L. Attitudes behind consumers’ willingness to use functional foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Westgren, R.E.; Cheney, M.M. Hierarchy of nutritional knowledge that relates to the consumption of a functional food. Nutrition 2005, 21, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brecic, R.; Gorton, M.; Barjolle, D. Understanding variations in the consumption of functional foods-evidence from Croatia. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Consumer acceptance of functional foods: Socio-demographic, cognitive and attitudinal determinants. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Mahmud, M.M.C.; Abdi, G.; Wanich, U.; Farooqi, M.Q.U.; Settapramote, N.; Khan, S.; Wani, S.A. New alternatives from sustainable sources to wheat in bakery foods: Science, technology, and challenges. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jian, C. Sustainable plant-based ingredients as wheat flour substitutes in bread making. Npj Sci. Food 2022, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Anjali; Rajput, R. Nutritional Enhancement of Baked Goods Using Alternative Flours: A Review. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2025, 17, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziharalambous, D.; Kaloteraki, C.; Potsaki, P.; Papagianni, O.; Giannoutsos, K.; Koukoumaki, D.I.; Sarris, D.; Gkatzionis, K.; Koutelidakis, A.E. Study of the Total Phenolic Content, Total Antioxidant Activity and In Vitro Digestibility of Novel Wheat Crackers Enriched with Cereal, Legume and Agricultural By-Product Flours. Oxygen 2023, 3, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, P.M.; Loredana, U.E.; Carmen, M.A.; Elena, P.E.; Alexandra, J. Chapter 15-Consumer Preferences and Expectations; Galanakis CMBT-T in W and BM, Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 431–458. [Google Scholar]

- Linnemann, A.R.; Meerdink, G.; Meulenberg, M.T.G.; Jongen, W.M.F. Consumer-oriented technology development. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1998, 9, 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Sparke, K.; Menrad, K. The Influence of Eating Habits on Preferences Towards Innovative Food Products. In Global Issues in Food Science and Technology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgopolova, I.; Teuber, R.; Bruschi, V. Consumers’ perceptions of functional foods: Trust and food-neophobia in a cross-cultural context. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, S.; Tsalis, G.; Lähteenmäki, L. How attitude towards food fortification can lead to purchase intention. Appetite 2019, 133, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ares, G.; Gámbaro, A. Influence of gender, age and motives underlying food choice on perceived healthiness and willingness to try functional foods. Appetite 2007, 49, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Raats, M.; Lähteenmäki, L. Methods Investigating Food-Related Behaviour; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Fantechi, T.; Contini, C.; Casini, L.; Lähteenmäki, L. Dietary dilemmas: Navigating trade-offs in food choice for sustainability, health, naturalness, and price. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 129, 105497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, V.; Zhou, Y. Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test: Overview; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McKight, P.; Najab, J. Kruskal-Wallis Test; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.L. The chi-square test of independence. Biochem. Medica 2013, 23, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, J. Spearman Rank Correlation. In Encycl Biostat; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, S. Whole Grains and their Bioactives: Composition and Health; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanillas, B. Gluten-related disorders: Celiac disease, wheat allergy, and nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2606–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Moreno, N.; Esparza, I.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C. Antioxidant Properties of Bioactive Compounds in Fruit and Vegetable Waste. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Géci, A.; Nagyová, L.; Rybanská, J. Impact of sensory marketing on consumer´s buying behaviour. Potravinarstvo 2017, 11, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicová, Ľ.; Predanocyová, K.; Kádeková, Z.; Košičiarová, I. Slovak Consumers´ Perception of Bakery Products and Their Offer in Retails. Potravin. Slovak J. Food Sci. 2020, 14, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soóki, M.; Májek, M.; Poláková, Z. Analyzing consumer behavior in bakery product markets: A journey through correspondence analysis and regression modeling. In Proceedings of the 17th International Scientific Conference, České Budějovice, Czech Republic, 2–3 November 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroustallaki, E. Market Research and Customer Preference Analysis: The Case of Consumer Flour. Master’s Thesis, Technical University of Crete, Kounoupidiana, Greece, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sedliaková, I.; Nagyova, L.; Holiencinova, M. Behavioural Studies of External Attributes of Bread and Pastry in Slovak Republic. Polityki Eur. Finans. Mark. 2014, 12, 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Golian, J.; Nagyová, L.; Andocsová, A.; Zajác, P.; Palkovič, J. Food safety from consumer perspective: Health safety. Potravin. Slovak J. Food Sci. 2018, 12, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, I.; Hiamey, S.E.; Afenyo, E.A. Students’ food safety concerns and choice of eating place in Ghana. Food Control 2014, 43, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šedík, P.; Zaguła, G.; Ivanišová, E.; Knazovicka, V.; Horska, E.; Kacaniova, M. Nutrition marketing of honey: Chemical, microbiological, antioxidant and antimicrobial profile. Potravinarstvo 2018, 12, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nagyová, L.; Andocsová, A.; Géci, A.; Zajác, P.; Palkovič, J.; Košičiarová, I.; Golian, J. Consumers´ awareness of food safety. Potravinarstvo 2019, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engindeniz, S.; Bolatova, Z. A Study on Consumption of Composite Flour and Bread in Global Perspective A study on consumption of composite flour and bread in global perspective. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 1962–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz-Żukowska, R.; Moskwa, J.; Gromkowska-Kępka, K.; Laskowska, E.; Laskowska, J.; Tomczuk, J.; Borawska, M.H. alin. Bakery products as a source of total dietary fiber in young adults. Rocz. Państwowego Zakładu Hig. 2016, 67, 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiou, A. Research on Consumer Preferences in Breakfast Cereal. Master’s Thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rezai, G.; Teng, P.K.; Mohamed, Z.; Shamsudin, M.N. Functional Food Knowledge and Perceptions among Young Consumers in Malaysia. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 2012, 6, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Herath, D.; Cranfield, J.; Henson, S. Who consumes functional foods and nutraceuticals in Canada? Results of cluster analysis of the 2006 survey of Canadians’ Demand for Food Products Supporting Health and Wellness. Appetite 2008, 51, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Stampfli, N.; Kastenholz, H. Consumers’ willingness to buy functional foods. The influence of carrier, benefit and trust. Appetite 2008, 51, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakiroǧlu, F.P.; Uçar, A. Consumer attitudes towards purchasing functional products. Prog. Nutr. 2018, 20, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, D.; Veneziani, M.; Sckokai, P.; Castellari, E. Consumer Willingness to Pay for Catechin-enriched Yogurt: Evidence from a Stated Choice Experiment. Agribusiness 2015, 31, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekoglu, F.B.; Ergen, A.; Inci, B. The Impact of Attitude, Consumer Innovativeness and Interpersonal Influence on Functional Food Consumption. Int. Bus. Res. 2016, 9, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, M.P.; Kalschne, D.L.; Benassi, M.D.T. Consumer’s attitude regarding soluble coffee enriched with antioxidants. Beverages 2018, 4, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakály, Z.; Kovács, S.; Pető, K.; Huszka, P.; Kiss, M. A modified model of the willingness to pay for functional foods. Appetite 2019, 138, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Scholderer, J.; Lähteenmäki, L. Consumer appeal of nutrition and health claims in three existing product concepts. Appetite 2009, 52, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wu, L. Food safety and consumer willingness to pay for certified traceable food in China. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1368–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, Ž.; Filipović, J.; Mugovsa, B. Consumer acceptance of Functional foods in Montenegro. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2014, 9, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Büyükkaragöz, A.; Bas, M.; Sağlam, D.; Cengiz, Ş.E. Consumers’ awareness, acceptance and attitudes towards functional foods in Turkey. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urala, N.; Lähteenmäki, L. Consumers’ changing attitudes towards functional foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, N.M.; Poryzees, G.H. Foods that help prevent disease: Consumer attitudes and public policy implications. Br. Food J. 1998, 100, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niva, M. “All foods affect health”: Understandings of functional foods and healthy eating among health-oriented Finns. Appetite 2007, 48, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urala, N.; Lähteenmäki, L. Hedonic ratings and perceived healthiness in experimental functional food choices. Appetite 2006, 47, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttolainen, M.; Luoto, R.; Uutela, A. Characteristics of users and nonusers of plant stanol ester margarine in Finland: An approach to study functional foods. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2001, 101, 1365–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Categories | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 44% |

| Female | 56% | |

| Age | 18–30 years | 15.2% |

| 30–45 years | 37.1% | |

| 45–65 years | 33.6% | |

| over 65 years | 14.1% | |

| Education level | Primary school | 3.3% |

| High school | 46.6% | |

| Institute of vocational training | 8.1% | |

| University | 28.2% | |

| Post-graduate studies/PhD | 6.9% | |

| Profession | Students | 9.2% |

| Private employees | 20.2% | |

| Civil servants | 10.3% | |

| Freelancers | 17.8% | |

| Farmers/artisans | 10% | |

| Police/military officers | 7.5% | |

| Household activities | 7.7% | |

| Pensioners | 15.2% | |

| Other | 1.1% | |

| Unemployed | 0.9% | |

| Income | EUR 450–1000 | 29.6% |

| EUR 1000–1500 | 44.1% | |

| EUR 1500–2000 | 17.7% | |

| Over EUR 2000 | 8.6% | |

| Marital status | Single | 24.1% |

| Married | 57.9% | |

| Divorced | 11.3% | |

| Widowed | 6.7% | |

| Number of adult members | 1 | 9.7% |

| 2 | 26.4% | |

| 3 | 20.3% | |

| 4 | 34.4% | |

| 5 | 9.1% | |

| Number of minor members | 0 | 50.9% |

| 1 | 21.9% | |

| 2 | 23% | |

| 3 | 4.2% | |

| Place of residence | Village | 20.5% |

| Small provincial town | 8.1% | |

| Provincial city | 48.5% | |

| Prefecture capital | 22.8% |

| Categories | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Do you consume bakery products? | Yes | 98.4% |

| No | 1.6% | |

| How often do you consume bakery products? | Every day | 47.6% |

| Every 3–5 days | 30.5% | |

| Once a week | 18.3% | |

| Rarely | 2.7% | |

| Once a month | 0.9% | |

| What type of bakery products do you usually consume? | Bread | 25.7% |

| Biscuits/Cookies | 23.9% | |

| Puff pastry | 20.8% | |

| Crackers | 14.2% | |

| Breadsticks | 10.8% | |

| Cakes | 4.5% | |

| How often do you purchase bakery products? | Every day | 37.6% |

| Every 2 weeks | 32.9% | |

| Once a week | 24.4% | |

| Rarely | 2.5% | |

| Once every 2 weeks | 1.4% | |

| Bakery products have nutritional value. | Strongly agree | 6.3% |

| Agree | 49.3% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 26.3% | |

| Disagree | 16.6% | |

| Strongly disagree | 1.6% | |

| Bakery products are good for our health. | Strongly agree | 3.1% |

| Agree | 44.4% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 31% | |

| Disagree | 19.4% | |

| Strongly disagree | 2% | |

| Which of the following statements matches your opinion on bakery products? | They represent an easy breakfast choice. They are fatty. | 46.6% 26.9% |

| They are not a healthy breakfast choice. | 10.3% | |

| I do not have an opinion. | 8.3% |

| Categories | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| I always want to try new and innovative food products. | Strongly agree | 15.2% |

| Agree | 67.1% | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 11.1% | |

| Disagree | 5.5% | |

| Strongly disagree | 1.1% | |

| Degree of trust towards innovative functional food products. | 1 | 0.8% |

| 2 | 2.8% | |

| 3 | 5.3% | |

| 4 | 12.1% | |

| 5 | 15.5% | |

| 6 | 49.8% | |

| 7 | 13.8% | |

| Do you know the existence of flours alternative to wheat? | Yes | 76.4% |

| No | 25.4% | |

| Would you try bakery products based on flours alternative to wheat? | Definitely yes | 69.5% |

| Probably yes | 18.6% | |

| Maybe yes maybe no | 6.9% | |

| Probably no | 4.7% | |

| What type of alternative flour would you choose for incorporation in bakery products? | Barley flour enriched with fiber (e.g., β-glucan) | 48% |

| Olive seed flour | 16.9% | |

| Chickpea flour | 15.2% | |

| Grape seed flour | 12.1% | |

| Lupine flour | 7.8% |

| Demographic Characteristics | Pearson Correlation Coefficient | |

|---|---|---|

| Intended use of flour | Gender | rs = 0.128 (p = 0.001) |

| Level of education | rs = 0.167 (p = 0.000) | |

| Age | rs = − 0.157 (p = 0.000) | |

| Type of flour usually purchased | Age | rs = 0.193 (p = 0.000) |

| Income | rs = 0.127 (p = 0.001) | |

| Level of education | rs = −0.132 (p = 0.001) | |

| Place of residence | rs = −0.132 (p = 0.001) | |

| Marital status | rs = 0.200 (p = 0.000) | |

| Most important factor in flour purchase | Marital status | rs = −0.173 (p = 0.000) |

| Place of residence | rs = −0.175 (p = 0.000) | |

| Amount of flour purchased/week | Age | rs = 0.270 (p = 0.000) |

| Level of education | rs = −0.373 (p = 0.000) | |

| Profession | rs = −0.116 (p = 0.000) | |

| Marital status | rs = −0.265 (p = 0.000) | |

| Place of residence | rs = 0.155 (p = 0.000) |

| Demographic Characteristics | Pearson Correlation Coefficient | |

|---|---|---|

| How often do you consume bakery products? | Gender | rs = −0.268 (p = 0.000) |

| Income | rs = 0.134 (p = 0.001) | |

| What type of bakery products do you usually consume? | Gender | rs = −0.132 (p = 0.001) |

| Income | rs = −0.154 (p = 0.000) | |

| Level of education | rs = 0.130 (p = 0.001) | |

| Age | rs = −0.236 (p = 0.000) | |

| Profession | rs = −0.133 (p = 0.001) | |

| Marital status | rs = −0.238 (p = 0.000) | |

| How often do you purchase bakery products? | Gender | rs = −0.354 (p = 0.000) |

| Level of education | rs = −0.103 (p = 0.009) | |

| Income | rs = 0.199 (p = 0.000) | |

| Number of minors in household | rs = 0.342 (p = 0.000) | |

| Number of adults in household | rs = 0.243 (p = 0.000) | |

| Bakery products are good for our health. | Place of residence | rs = 0.128 (p = 0.001) |

| Demographic Characteristics | Pearson Correlation Coefficient | |

|---|---|---|

| I always want to try new and innovative food products. | Age | rs = 0.098 (p = 0.013) |

| Income | rs = 0.116 (p = 0.003) | |

| Marital status | rs = 0.102 (p = 0.010) | |

| Place of residence | rs = 0.252 (p = 0.000) | |

| Number of minors in household | rs = 0.094 (p = 0.018) | |

| Number of adults in household | rs = 0.234 (p = 0.000) | |

| Degree of trust towards innovative functional food products. | Gender | rs = −0.134 (p = 0.000) |

| Age | rs = 0.123 (p = 0.002) | |

| Income | rs = 0.228 (p = 0.000) | |

| Marital status | rs = 0.131 (p = 0.001) | |

| Place of residence | rs = 0.319 (p = 0.000) | |

| Number of minors in household | rs = 0.146 (p = 0.000) | |

| Number of adults in household | rs = 0.369 (p = 0.000) | |

| Are you familiar with the existence of bakery products from alternative flours? | Gender | rs = −0.165 (p = 0.000) |

| Age | rs = 0.177 (p = 0.000) | |

| Level of education | rs = −0.204 (p = 0.000) | |

| Marital status | rs = −0.106 (p = 0.008) | |

| Number of adults in household | rs = 0.100 (p = 0.012) | |

| Would you try bakery products made from flours alternatives to wheat? | Income | rs = 0.211 (p = 0.000) |

| Level of education | rs = −0.086 (p = 0.029) | |

| Place of residence | rs = 0.185 (p = 0.000) | |

| Number of minors in household | rs = 0.121 (p = 0.002) | |

| Number of adults in household | rs = 0.417 (p = 0.000) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatziharalambous, D.; Koutelidakis, A.E. Study of Influencing Factors in Consumer Attitude, Consumption, and Purchasing Frequency in the Market of Flour and Bakery Products in Greece. Dietetics 2025, 4, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4040048

Chatziharalambous D, Koutelidakis AE. Study of Influencing Factors in Consumer Attitude, Consumption, and Purchasing Frequency in the Market of Flour and Bakery Products in Greece. Dietetics. 2025; 4(4):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4040048

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatziharalambous, Despina, and Antonios E. Koutelidakis. 2025. "Study of Influencing Factors in Consumer Attitude, Consumption, and Purchasing Frequency in the Market of Flour and Bakery Products in Greece" Dietetics 4, no. 4: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4040048

APA StyleChatziharalambous, D., & Koutelidakis, A. E. (2025). Study of Influencing Factors in Consumer Attitude, Consumption, and Purchasing Frequency in the Market of Flour and Bakery Products in Greece. Dietetics, 4(4), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics4040048