Content, Quality and Accuracy of Online Nutrition Resources for the Prevention and Treatment of Dementia: A Review of Online Content

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.4.1. Characterisation of Web Page Content

2.4.2. Quality of Web Page Content

2.4.3. Accuracy of Nutrition-Related Web Page Content

3. Results

3.1. Webpage Topics

3.2. Quality of Webpage Content

3.3. Accuracy of Nutrition-Related Webpage Content

3.3.1. Webpage Information Accuracy by Guideline

3.3.2. Webpage Information Accuracy by Website Type

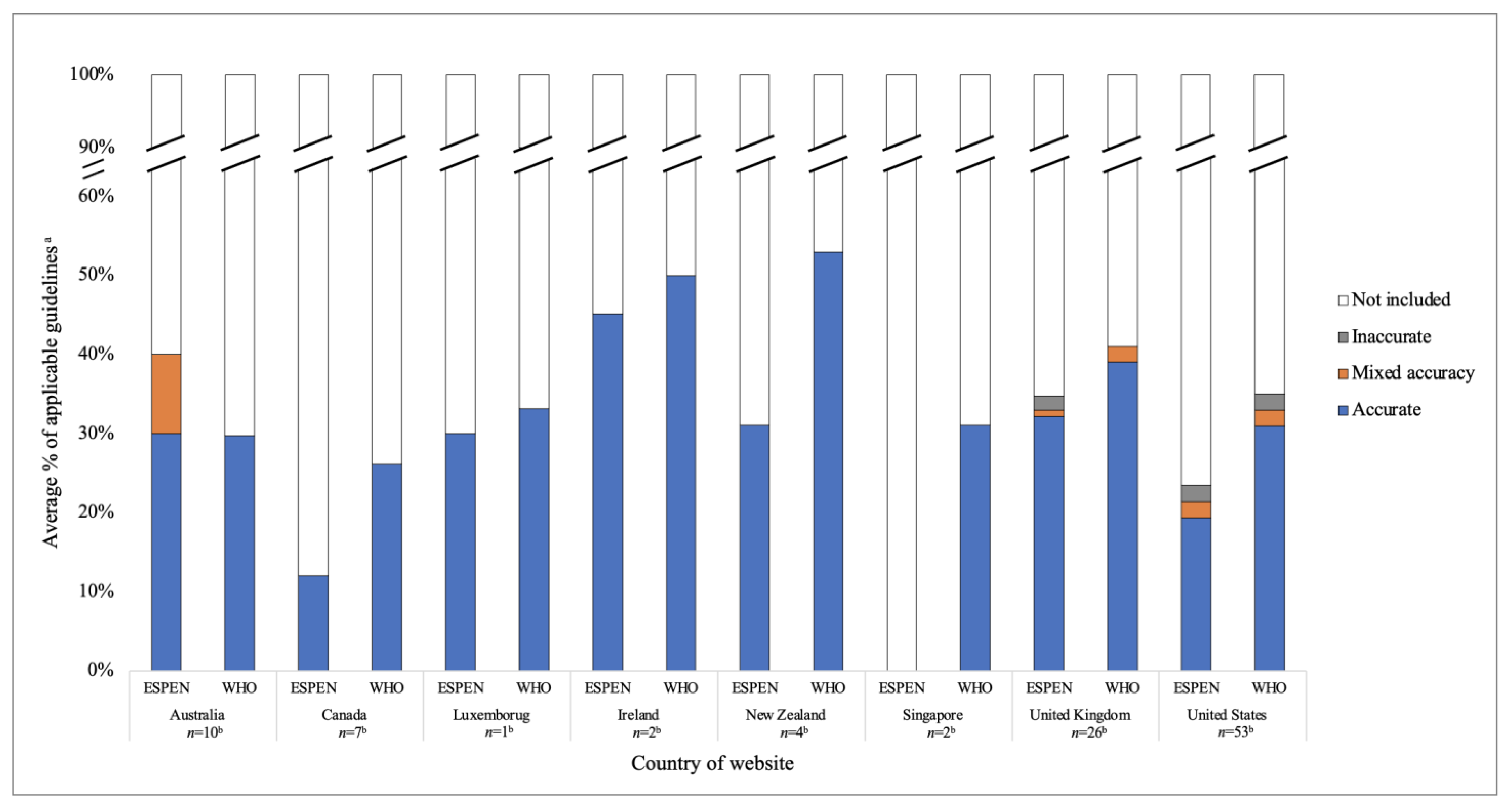

3.3.3. Webpage Information Accuracy by Website Country of Origin

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Study Implications and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020, 16, 391–460. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: WHO Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Farrow, M.; O’Conner, E. Targeting Brain, Body and Heart for Cognitive Health and Dementia; Alzheimer’s Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deckers, K.; van Boxtel, M.P.J.; Schiepers, O.J.G.; de Vugt, M.; Muñoz Sánchez, J.L.; Anstey, K.J.; Brayne, C.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Engedal, K.; Kivipelto, M.; et al. Target risk factors for dementia prevention: A systematic review and Delphi consensus study on the evidence from observational studies. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, A.; Sugimoto, T.; Kitamori, K.; Saji, N.; Niida, S.; Toba, K.; Sakurai, T. Malnutrition is Associated with Behavioral and Psychiatric Symptoms of Dementia in Older Women with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Early-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kai, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Amano, K.; Tanaka, H.; Fukuhara, R.; Ikeda, M. Relationship between Eating Disturbance and Dementia Severity in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, I.; Clerici, F.; Rossi, A.; Cucumo, V.; Ghiretti, R.; Maggiore, L.; Pomati, S.; Galimberti, D.; Scarpini, E.; Mariani, C.; et al. Weight Loss Predicts Progression of Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.; Behrens, S.; Schwartz, S.; Wengreen, H.; Corcoran, C.D.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Tschanz, J.T. Nutritional Status is Associated with Faster Cognitive Decline and Worse Functional Impairment in the Progression of Dementia: The Cache County Dementia Progression Study1. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 52, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payette, H.; Coulombe, C.; Boutier, V.; Gray-Donald, K. Nutrition risk factors for institutionalization in a free-living functionally dependent elderly population. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2000, 53, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faxén-Irving, G.; Basun, H.; Cederholm, T. Nutritional and cognitive relationships and long-term mortality in patients with various dementia disorders. Age Ageing 2005, 34, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Cain, R.; Meyer, C. How People with Dementia and their Carers Adapt their Homes. A Qualitative Study. Dementia 2019, 18, 1199–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Cain, R.; Meyer, C. Seeking relational information sources in the digital age: A study into information source preferences amongst family and friends of those with dementia. Dementia 2020, 19, 766–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soong, A.; Au, S.T.; Kyaw, B.M.; Theng, Y.L.; Tudor Car, L. Information needs and information seeking behaviour of people with dementia and their non-professional caregivers: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruffydd, E.; Randle, J. Alzheimer’s disease and the psychosocial burden for caregivers. Community Pract. J. Community Pract. Health Visit. Assoc. 2006, 79, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless, M.; Augoustinos, M.; LeCouteur, A. “Your Brain Matters”: Issues of Risk and Responsibility in Online Dementia Prevention Information. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xie, B. Quality of health information for consumers on the web: A systematic review of indicators, criteria, tools, and evaluation results. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 66, 2071–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.A.; Nikzad-Terhune, K.A.; Gaugler, J.E. A Systematic Evaluation of Online Resources for Dementia Caregivers. J. Consum. Health Internet 2009, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, W.A.; Prorok, J.C.; Seitz, D.P. Content and quality of information provided on Canadian dementia websites. Can. Geriatr. J. CGJ 2013, 16, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, J.M.; Feng, T.L. Health Advice in a Digital World: Quality and Content of Online Information about the Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 55, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkert, D.; Chourdakis, M.; Faxen-Irving, G.; Frühwald, T.; Landi, F.; Suominen, M.H.; Vandewoude, M.; Wirth, R.; Schneider, S.M. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementia. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 1052–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). JBI Man. Evid. Synth. 2020. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- StatCounter. Search Engine Market Share Worldwide. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share#monthly-202106-202106-bar (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Southern Adventist University. Google & Google Scholar: Boolean Operators. Available online: https://southern.libguides.com/google/boolean (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Google. Trends Help. Available online: https://support.google.com/trends/answer/4355212 (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern, M. Over 25% of People Click the First Google Search Result. Available online: https://www.searchenginejournal.com/google-first-page-clicks/374516/#close (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Storr, T.; Maher, J.; Swanepoel, E. Online nutrition information for pregnant women: A content analysis: Online nutrition information for pregnant women. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, e12315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EBizMBA. Top 15 Best Health Websites | October 2021. Available online: http://www.ebizmba.com/articles/health-websites (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Rasool, T.; Warraich, N.F. Does Quality matter: A systematic review of information quality of E-Government websites. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Galway, Ireland, 4–6 April 2018; pp. 433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Ogle, G.; Bowling, K. Unique Peaks: The Definition, Role and Contribution of Peak Organizations in the South Australian Health and Community Services Sector; South Australian Council of Social Service: Unley, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health. 8.1 Peak Bodies. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/cardio-pubs-review~cardio-pubs-review-08-currentprograms~cardio-pubs-review-08-currentprograms-1-pb (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Keller, H.H.; Smith, D.; Kasdorf, C.; Dupuis, S.; Schindel Martin, L.; Edward, G.; Cook, C.; Genoe, R. Nutrition education needs and resources for dementia care in the community. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2008, 23, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charnock, D.; Shepperd, S.; Needham, G.; Gann, R. DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 1999, 53, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerminara, C.; Santarone, M.E.; Casarelli, L.; Curatolo, P.; El Malhany, N. Use of the DISCERN tool for evaluating web searches in childhood epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014, 41, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.; Raeside, R.; Singleton, A.; Redfern, J.; Partridge, S.R. Limited Engaging and Interactive Online Health Information for Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Australian Websites. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Usman, M.; Muhammad, F.; Rehman, S.U.; Khan, I.; Idrees, M.; Irfan, M.; Glowacz, A. Evaluation of Quality and Readability of Online Health Information on High Blood Pressure Using DISCERN and Flesch-Kincaid Tools. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Tangney, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Sacks, F.M.; Barnes, L.L.; Bennett, D.A.; Aggarwal, N.T. MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimers Dement. 2015, 11, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Tangney, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Sacks, F.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Aggarwal, N.T. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015, 11, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerhoi, M.G.; Rollefstad, S.; Olsen, S.U.; Semb, A.G. The effect of brief versus individually tailored dietary advice on change in diet, lipids and blood pressure in patients with inflammatory joint disease. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 62, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, R.; Yachi, Y.; Yoshizawa, S.; Horikawa, C.; Heianza, Y.; Sugawara, A.; Sone, Y.; Kondo, K.; Shimano, H.; Saito, K.; et al. Quality and accuracy of Internet information concerning a healthy diet. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 64, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkouskou, K.; Markaki, A.; Vasilaki, M.; Roidis, A.; Vlastos, I. Quality of nutritional information on the Internet in health and disease. Hippokratia 2011, 15, 304–307. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, A.J.; George, J.; Woodward, M.C.; Ames, D.; Brodaty, H.; Elliott, R.A. Dietary supplement use in older people attending memory clinics in Australia. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2016, 21, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scullard, P.; Peacock, C.; Davies, P. Googling children’s health: Reliability of medical advice on the internet. Arch. Dis. Child. 2010, 95, 580–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victoria State Government Finding Reliable Health Information. Available online: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/servicesandsupport/finding-reliable-health-information#rpl-skip-link (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Palmour, N.; Vanderbyl, B.L.; Zimmerman, E.; Gauthier, S.; Racine, E. Alzheimer’s Disease Dietary Supplements in Websites. HEC forum. 2013, 25, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahche, J.J.; Bailey, R.L.; Potischman, N.; Dwyer, J.T. Dietary Supplement Use Was Very High among Older Adults in the United States in 2011–2014. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1968–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangvik, R.J.; Bruvik, F.K.; Drageset, J.; Kyte, K.; Hunskar, I. Effects of oral nutrition supplements in persons with dementia: A systematic review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease: 2018 Update; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Lea, W. Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020; Department of Health: London, UK, 2015.

- Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council. National Framework for Action on Dementia 2015-2019; Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2015.

- Teper, M.H.; Godard-Sebillotte, C.; Vedel, I. Achieving the Goals of Dementia Plans: A Review of Evidence-Informed Implementation Strategies. Healthc. Policy 2019, 14, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, J.C.; Fowler, K.C.; De Guzman, M.F.P. In support of a national dementia plan: A follow-up study for dementia incidence and risk profiling in Filipino homes. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ddumba, I. Implementation of Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia (GAPD) in Sub-Saharan Africa: Comprehensive reviews. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020, 16, e043363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. A Dementia Strategy for Canada: Together We Aspire; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, ON, USA, 2019.

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchens, B.; Harle, C.A.; Li, S. Quality of health-related online search results. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 57, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostry, A.; Young, M.L.; Hughes, M. The quality of nutritional information available on popular websites: A content analysis. Health Educ. Res. 2007, 23, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaValley, S.A.; Kiviniemi, M.T.; Gage-Bouchard, E.A. Where people look for online health information. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2017, 34, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia: Assessment, Management and Support for People Living with Dementia and Their Carers NICE Guideline NG97; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alzhimer’s Disease International publication team. From Plan to Impact: Progress towards Targets of the Global Action Plan on Dementia; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alzhimer’s Disease International. From Plan to Impact IV: Progress towards Targets of the WHO Global Action Plan on Dementia; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, S.J.; Wolf, M.S.; Brach, C. Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): A new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 96, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira do Prado, L.; Carpentier, C.; Preau, M.; Schott, A.-M.; Dima, A.L. Behavior Change Content, Understandability, and Actionability of Chronic Condition Self-Management Apps Available in France: Systematic Search and Evaluation. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e13494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Webpage Characteristics | Webpage DISCERN Score a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Web Pages, n (%) | Mean b | SD | |

| Website type | Government c | 13 (12.4) | 52.2 | 6.8 |

| Organisation d | 65 (61.9) | 50.0 | 7.9 | |

| Commercial e | 27 (25.7) | 50.3 | 7.5 | |

| Webpage context | Prevention | 52 (49.5) | 47.5 | 7.2 |

| Treatment | 42 (40.0) | 53.1 | 6.7 | |

| Both | 11 (10.5) | 53.5 | 8.4 | |

| Website country of origin | Australia | 10 (9.5) | 53.9 | 7.3 |

| Canada | 7 (6.7) | 48.6 | 7.7 | |

| Luxembourg | 1 (1.0) | 53.0 | - | |

| Ireland | 2 (1.9) | 65.0 | 5.7 | |

| New Zealand | 4 (3.8) | 48.5 | 5.4 | |

| Singapore | 2 (1.9) | 42.5 | 7.8 | |

| United Kingdom | 26 (24.8) | 51.5 | 7.4 | |

| United States | 53 (50.5) | 49.2 | 7.4 | |

| Nutrition Related Topics | Webpages, n (%) a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| General information | Background information |

| 11 (10.5) |

| 45 (42.9) | ||

| 40 (38.1) | ||

| 67 (63.8) | ||

| Help and support |

| 59 (56.2) | |

| 39 (37.1) | ||

| Prevention and/or treatment information | Diet |

| 81 (77.1) |

| 53 (50.5) | ||

| 8 (7.6) | ||

| 70 (66.7) | ||

| 37 (35.2) | ||

| 12 (11.4) | ||

| 28 (26.7) | ||

| 30 (28.6) | ||

| Nutrition-specific strategies |

| 18 (17.1) | |

| 34 (32.4) | ||

| 18 (17.1) | ||

| 35 (33.3) | ||

| 9 (8.6) | ||

| Category | ESPEN Guideline a | Total Applicable b, n (%) | Total Included c, n (%) | Accurate d, n (%) | Mixed Accuracy d, n (%) | Inaccurate d, n (%) | Not Included e, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening and assessment | 1. Malnutrition screening | 37 (35.2) | 5 (13.5) | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (30.5) |

| 2. Monitoring and documentation of body weight | 37 (35.2) | 8 (21.6) | 8 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (27.6) | |

| Strategies to support oral nutrition | 3. Mealtime environmental factors | 42 (40.0) | 30 (71.4) | 30 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (11.4) |

| 4. Nutrition for individual needs and preferences | 42 (40.0) | 36 (85.7) | 36 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (5.7) | |

| 5. Adequate food intake and support | 42 (40.0) | 37 (88.1) | 37 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (4.8) | |

| 6. Appetite stimulants | 41 (39.0) | 3 (7.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 38 (36.2) | |

| 7. Educating caregivers | 43 (41.0) | 39 (90.7) | 39 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.8) | |

| 8. Causes of malnutrition | 44 (41.0) | 32 (74.4) | 32 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (10.5) | |

| 9. Dietary restrictions | 44 (41.9) | 15 (34.1) | 14 (93.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (17.6) | |

| Oral supplementation -nutrient supplementation | 10a. Omega-3-fatty acid | 34 (32.4) | 28 (82.4) | 22 (78.6) | 3 (10.7) | 3 (10.7) | 6 (5.7) |

| 10b. Vitamin B1 | 97 (92.4) | 19 (19.6) | 17 (89.5) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.3) | 78 (74.3) | |

| 10c. Vitamin B6, vitamin B12 and/or folic acid | 97 (93.3) | 24 (24.7) | 19 (79.2) | 3 (12.5) | 2 (8.3) | 73 (69.5) | |

| 10d. Vitamin E | 98 (93.3) | 26 (26.5) | 20 (76.9) | 4 (15.4) | 2 (7.7) | 72 (68.6) | |

| 10e. Selenium | 97 (92.4) | 15 (15.5) | 13 (86.7) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | 82 (78.1) | |

| 10f. Copper | 97 (92.4) | 15 (15.5) | 14 (93.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 82 (78.1) | |

| 10g. Vitamin D | 96 (91.4) | 22 (22.9) | 17 (77.3) | 2 (9.1) | 3 (13.6) | 74 (70.5) | |

| Oral supplementation -oral nutritional supplements | 11. ONS to improve nutritional status | 58 (55.2) | 9 (15.5) | 9 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 49 (46.7) |

| 12. ONS to correct/prevent further cognitive impairment | 86 (81.9) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 84 (80.0) | |

| 13. Special medical foods | 86 (81.9) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 84 (80.0) | |

| 14. Other nutritional products | 95 (90.5) | 12 (12.6) | 7 (58.3) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 83 (79.0) | |

| Artificial nutrition and hydration | 15. Patient prognosis and preferences | 7 (6.7) | 6 (85.7) | 6 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1) |

| 16. Tube feeding for mild/moderate dementia | 6 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (5.7) | |

| 17. Tube feeding in severe dementia | 7 (6.7) | 6 (85.7) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1) | |

| 18. Parenteral nutrition | 7 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (6.7) | |

| 19. Parenteral fluids | 7 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (6.7) | |

| 20. Artificial nutrition in terminal phase | 7 (6.7) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (4.8) |

| Category | WHO Guideline a | Total Applicable b, n (%) | Total Included c, n (%) | Accurate d, n (%) | Mixed Accuracy d, n (%) | Inaccurate d, n (%) | Not Included e, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrition intervention | 1a. Mediterranean-like diet | 94 (89.5) | 51 (54.3) | 48 (94.1) | 3 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 43 (41.0) |

| 1b. Healthy and balanced diet | 95(90.5) | 70 (73.7) | 67 (95.7) | 3 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (23.8) | |

| 1c. Vitamins B and E, PUFA and multi-complex supplementation | 91 (86.7) | 32 (35.2) | 25 (78.1) | 4 (12.5) | 3 (9.4) | 59 (56.2) | |

| Interventions for alcohol use disorder | 2. Reduce/cease harmful drinking | 63 (60.0) | 21 (33.3) | 21 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 42 (40) |

| Weight management | 3. Interventions for mid-life overweight and/or obesity | 62 (59.0) | 9 (14.5) | 9 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 53 (50.5) |

| Management of hypertension | 4. Management of hypertension | 62 (59.0) | 15 (24.2) | 15 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 47 (44.8) |

| Management of diabetes mellitus | 5. Management of diabetes | 62 (59.0) | 8 (12.9) | 8 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 54 (51.4) |

| Management of dyslipidaemia | 6. Management of dyslipidaemia | 62 (59.0) | 8 (12.9) | 8 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 54 (51.4) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Nguyen, J.; O’Leary, F. Content, Quality and Accuracy of Online Nutrition Resources for the Prevention and Treatment of Dementia: A Review of Online Content. Dietetics 2022, 1, 148-163. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics1030015

Lee J, Nguyen J, O’Leary F. Content, Quality and Accuracy of Online Nutrition Resources for the Prevention and Treatment of Dementia: A Review of Online Content. Dietetics. 2022; 1(3):148-163. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics1030015

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Justine, Julie Nguyen, and Fiona O’Leary. 2022. "Content, Quality and Accuracy of Online Nutrition Resources for the Prevention and Treatment of Dementia: A Review of Online Content" Dietetics 1, no. 3: 148-163. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics1030015

APA StyleLee, J., Nguyen, J., & O’Leary, F. (2022). Content, Quality and Accuracy of Online Nutrition Resources for the Prevention and Treatment of Dementia: A Review of Online Content. Dietetics, 1(3), 148-163. https://doi.org/10.3390/dietetics1030015