1. Introduction

Tropical trees that combine cultural value, ecological services, and economic potential play an increasingly important role in the sustainability of rural landscapes. Among these,

Inga edulis Mart. (Fabaceae) is one of the most emblematic species of the Amazon Basin [

1]. Commonly known as “guaba” or “ice-cream bean,” it is valued for its edible pods, which contain a sweet, cotton-textured pulp. It is also valued for its fast growth and nitrogen-fixing ability that enhance soil fertility, and for providing shade for crops such as coffee and cacao [

2]. Because of its versatility and resilience,

I. edulis has become a keystone component of agroforestry systems across tropical America, where it supports both livelihoods and ecosystem functioning [

3].

In recent years, the species has gained attention as a model for understanding incipient domestication processes in tropical trees, where human selection for desirable traits such as pod size or fruit sweetness can rapidly shape population structure [

4]. For example, a study on

I. edulis from the Peruvian Amazon [

5] demonstrated that cultivated populations display significantly longer pods but reduced allelic richness compared to their wild counterparts, indicating an early stage of domestication and a potential loss of genetic diversity. These findings highlight the importance of evaluating how different cultivation practices influence both productivity and genetic resources across the species’ range, although studies from other regions are basically absent. In southern Ecuador, two main cultivation contexts predominate: agroforestry systems, in which

I. edulis is deliberately planted to provide shade in coffee and cacao plantations, and home gardens, which are frequently composed of pre-existing trees retained during land clearing or occasionally supplemented by planting. In home gardens, these trees are typically managed for household use, with fruit production serving mainly subsistence purposes.

Understanding how cultivation contexts influence I. edulis diversity is crucial for integrating productivity, cultural practices, and in situ conservation. Assessing variation in fruit traits and genetic diversity across management systems can help identify trade-offs between yield and genetic heterogeneity, providing insights for the sustainable use of this Amazonian fruit tree. Accordingly, this study aimed to (1) quantify differences in pod size between I. edulis trees grown in agroforestry and home-garden systems in southern Ecuador, (2) assess genetic diversity patterns using microsatellite markers, and (3) discuss the implications of these patterns for conservation and sustainable management of I. edulis in traditional landscapes.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Morphological Measurements

Fieldwork was conducted in southern Ecuador, sampling adult I. edulis individuals across two contrasting cultivation contexts: agroforestry plantations and traditional home gardens. A total of 62 trees were sampled, comprising 32 individuals from agroforestry systems and 30 individuals from home gardens.

In home gardens, I. edulis typically occurs as one or two trees per garden, which limits within-site replication. Therefore, our sampling in this context prioritized the number of independent home gardens rather than the number of trees per site. In contrast, agroforestry plantations commonly contain multiple I. edulis individuals, allowing a greater number of trees to be sampled per plantation while maintaining spatial independence across farms. This sampling strategy was designed to maximize biological replication at the level of individual trees while accurately reflecting the socio-ecological structure of each management system. However, this structure may result in differences in relatedness or seed provenance among sampled individuals, particularly in agroforestry plantations.

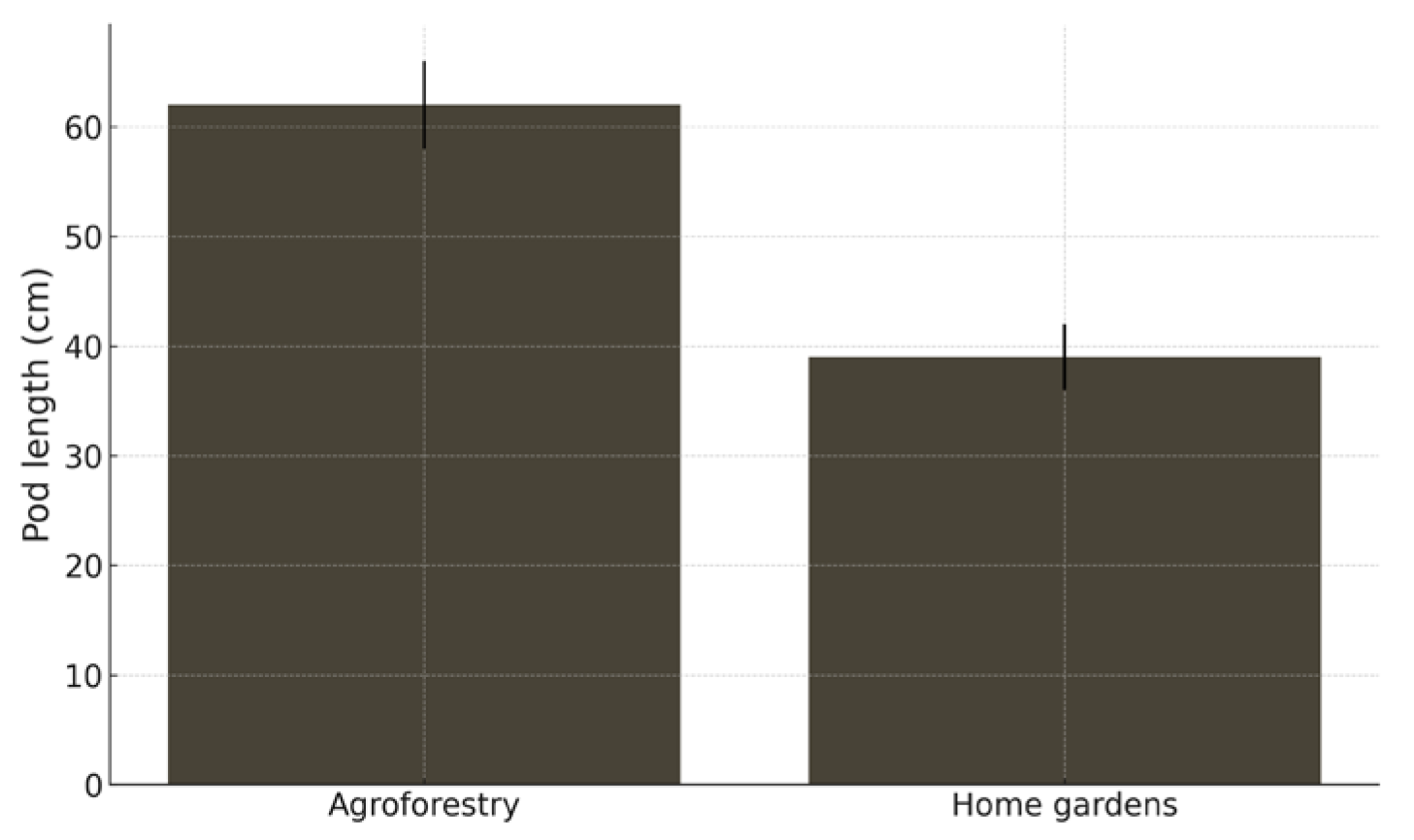

For each tree, ten mature pods were collected and measured for pod length (cm) using a digital caliper, resulting in a total of 620 fruits. Pod length was measured along the longitudinal axis from the point of peduncle attachment (pod base) to the distal apex. To avoid pseudoreplication, pod measurements were averaged per individual tree, and individual trees were used as the unit of replication in subsequent analyses. Differences in mean pod length between cultivation systems were tested using a two-sample t-test, with cultivation system as the grouping factor. Given the exploratory nature of the study, analyses were conducted at the tree level to provide a first-order comparison between management systems rather than to partition variance across hierarchical levels.

2.2. DNA Extraction and Genotyping

Leaf samples from the above adult trees were collected in each population, brought to the laboratory, and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. Total genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Plant Minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stored at −80 °C. To genotype all samples, we used four microsatellite (SSR) loci previously developed for

Inga edulis species [

4] plus one locus (

Pel5) that was previously developed for

Pithecellobium elegans by [

6] and was successfully transferred to

I. edulis (

Table 1). Thus, these primers were selected because they have been previously validated in

Inga species and because of their high polymorphism. This allows direct comparison with previous studies. SSR amplifications were performed in 15 μL reactions containing 1.25 U MyTaq DNA polymerase and 1× MyTaq Reaction Buffer (Meridian Bioscience, London, UK), 0.4 μM Primer F-FAM and R, and 100 ng of genomic DNA carried and amplified as described in [

4]. PCR products were genotyped on an Applied Biosystems 3130XL Genetic Analyzer using 2 μL of amplified DNA, 12 μL of Hi-Di formamide, and 0.4 μL of GeneScan-600 (LIZ) size standard (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Genotyping of microsatellite fragments was conducted on an AB 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies Inc., New York, NY, USA). Allele sizes were determined using GeneMarker 3.1. (Softgenetics, State College, PA, USA).

2.3. Genetic Diversity Analysis

For each population, the mean number of alleles per locus (A), effective number of alleles (Ne), observed (Ho) and expected heterozygosity (He), and fixation index (FIS) were calculated using GenAlEx v6.51 [

7]. Differences in diversity indices between cultivation systems were tested using permutation procedures (10,000 iterations).

4. Discussion

This exploratory study identified patterns consistent with a potential trade-off between productivity-oriented management and levels of genetic diversity in

Inga edulis. Trees in agroforestry systems were associated with larger pods on average, while exhibiting lower overall genetic variability compared with home gardens. Similar associations have been reported for tropical perennial species under early stages of domestication, where recurrent selection for desirable phenotypes may contribute to increased genetic homogeneity within managed populations [

4,

5,

8]. In such contexts, selective propagation of a limited number of preferred individuals, together with seed exchange occurring within relatively restricted farmer networks, likely constrains the influx of new alleles [

9].

Rather than comparing wild and cultivated populations, this study focused on differences within human-managed landscapes, where management intensity varies but gene flow remains active. This approach allowed us to explore how cultivation context may be associated with phenotypic and genetic patterns during early stages of domestication. In this light, our findings complement and extend those reported by [

5], who documented reduced allelic richness in cultivated

I. edulis trees relative to wild populations, alongside selection for longer pods in the Peruvian Amazon. Importantly, our results show that genetic differentiation can also emerge within cultivated systems themselves. Agroforestry plantations in southern Ecuador showed patterns of phenotypic enlargement and reduced genetic diversity similar to those reported for cultivated stands in Peru [

5], despite the absence of direct wild references in our dataset. Such comparisons should be interpreted cautiously, as differences in the regional context or the sampling design preclude direct equivalence. Although our markers are highly polymorphic and have been previously validated for

I. edulis and related taxa [

4,

5], their reduced coverage limits the robustness of estimates of genetic diversity and fixation indices and increases sensitivity to locus-specific effects. As such, the patterns reported here should be interpreted as indicative first-order contrasts between management systems rather than definitive evidence of genetic erosion or domestication trajectories.

Nevertheless, our data suggests that home gardens may function as microcosms of diversity that help mitigate genetic erosion in I. edulis. In southern Ecuador, farmers frequently plant seeds obtained from neighboring communities, local markets, or nearby semi-wild trees, promoting ongoing gene flow across the landscape. Although both cultivation systems exhibited positive fixation indices, the lower FIS values observed in home gardens suggest weaker heterozygote deficits, likely reflecting higher connectivity and less structured seed sourcing rather than strong inbreeding. The positive FIS values in both systems may also partly reflect Wahlund effects arising from the pooling of individuals originating from multiple seed sources or subpopulations, while the contribution of null alleles cannot be entirely ruled out given the limited number of loci used. However, in agroforestry plantations, where multiple trees were sampled within farms, shared seed sources or localized planting practices may increase relatedness among individuals, potentially contributing to the observed patterns of genetic diversity and fixation indices.

Beyond genetic patterns, the phenotypic differences observed among I. edulis populations also point to substantial plasticity. Larger pods in agroforestry systems likely result from a combination of potential genetic selection and favorable growing conditions, such as enhanced soil fertility, greater light availability, and targeted pruning that channels resources towards reproductive structures. Because this study is based on observational field data, these effects cannot be fully disentangled in the absence of common-garden experiments or other forms of experimental control. Moreover, pod size alone represents an incomplete proxy for fitness. While larger fruits may increase market value and enhance seed dispersal, they can also entail higher energetic costs or trade-offs with other traits, including seed viability or germination performance.

In sum, this study highlights the potential value of viewing agroforestry systems and home gardens as complementary rather than competing components of tropical agricultural landscapes. Although based on a regional and exploratory dataset, the patterns observed may be informative for other tropical tree species, where productivity-oriented management coexists with ongoing gene flow and informal seed exchange [

9,

10]. Participatory initiatives such as community seed banks, farmer-led selection programs, and nurseries incorporating diverse local genotypes could further strengthen this role. Future research should also expand sampling to wild and semi-wild populations, incorporate higher-resolution genomic tools to detect selection signatures, and assess how landscape connectivity and cultural practices jointly shape the genetic structure of

I. edulis across the Andes–Amazon gradient.