Heat Stress in Chillies: Integrating Physiological Responses and Heterosis Breeding Approaches for Enhanced Resilience †

Abstract

1. Introduction

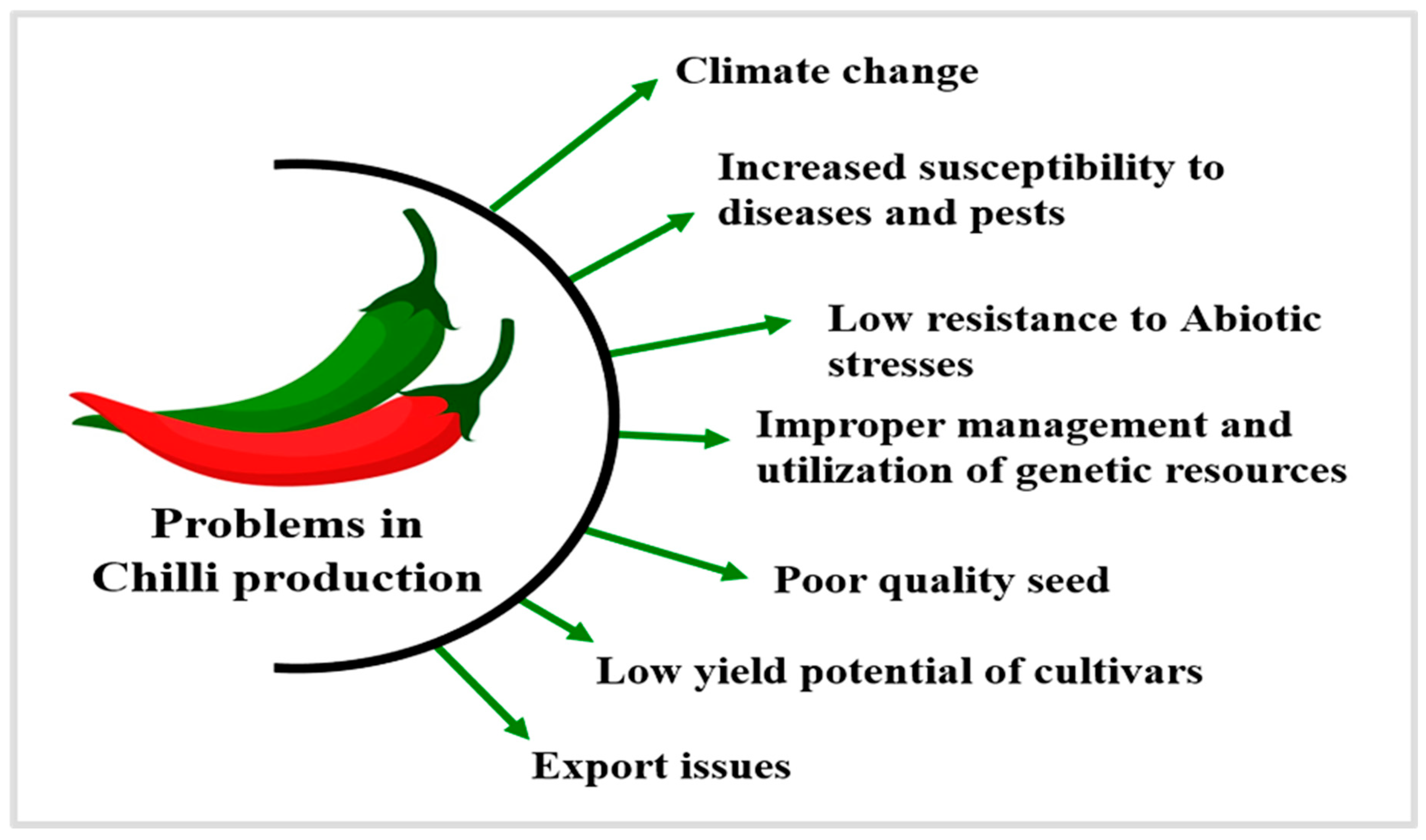

2. Major Problems in Chilli Production

3. Heat Stress in Chilli Pepper

4. Reproductive Response of Chilli to Heat Stress

5. Vegetative Response of Chilli to Heat Stress

6. Biochemical Response of Chilli to Heat Stress

7. Mechanism of Heat Stress Tolerance in Chillies

8. Strategies to Improve Heat Stress Tolerance in Chillies

9. Breeding in Chilli Pepper

10. Objectives and Techniques of Breeding in Chilli

11. Heterosis Breeding and Its Application

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of National Food Security and Research (MNFSR). Fruits, Vegetables, and Condiments Statistics of Pakistan 2022–23. Available online: https://mnfsr.gov.pk/PublicationDetail/ZDFlMzNiZDUtMDMzNC00N2RhLWI5YjUtNGMwMzM3NTEyYWZi (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Reddy, M.; Kumar, R.; Ponnam, N.; Prasad, I.; Barik, S.P.; Pydi, R.; Pasupula, K. Chili: Breeding and genomics. Veg. Sci. 2023, 1, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, T.S.; Srivastava, A.; Tomar, B.S.; Khar, A.; Yadav, H.; Jain, P.K.; Mangal, M. Insights from morpho-physio-biochemical and molecular traits of hot pepper genotypes contrasting for heat-tolerance. Indian J. Hortic. 2024, 81, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A.; Singh, K.; Khar, A.; Parihar, B.R.; Tomar, B.S.; Mangal, M. Morphological, biochemical, and molecular insights on responses to heat stress in chilli. Indian J. Hortic. 2022, 79, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deva, C.R.; Urban, M.O.; Challinor, A.J.; Falloon, P.; Svitákova, L. Enhanced leaf cooling is a pathway to heat tolerance in common bean. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.G.; Rafii, M.Y.; Ismail, M.R.; Malek, M.A.; Abdul Latif, M. Heritability and genetic advance among chili pepper genotypes for heat tolerance and morphophysiological characteristics. Sci. World J. 2014, 1, 308042. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, S.C.; Chakraborty, S.; Dreccer, M.F.; Howden, S.M. Plant adaptation to climate change—Opportunities and priorities in breeding. Crop Pasture Sci. 2012, 63, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Cheema, D.S.; Dhaliwal, M.S.; Garg, N. Heterosis and combining ability for earliness, plant growth, yield and fruit attributes in hot pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) involving genetic and cytoplasmic-genetic male sterile lines. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 168, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfaraz, M.; Veersain, M.; Yadav, S.; Srivastav, P. Seed production of chilli (Capsicum frutescens). In Organic Horticulture; Bright Sky Publications: Delhi, India, 2022; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Soyam, S.R.; Apturkar, A.M. A review: Breeding in chilli. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2020, 9, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, Y.R.; Umalkar, G.V. Productive mutations induced in Capsicum annuum by physical and chemical mutagens. IV Int. Symp. Seed Res. Hortic. 1988, 253, 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Selvakumar, R.; Manjunathagowda, D.C.; Singh, P.K. Capsicum: Breeding Prospects and Perspectives for Higher Productivity. In Capsicum—Current Trends and Perspectives; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arimboor, R.; Natarajan, R.B.; Menon, K.R.; Chandrasekhar, L.P.; Moorkoth, V. Red pepper (Capsicum annuum) carotenoids as a source of natural food colors: Analysis and stability—A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 52, 1258–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, K.L.; Hastorf, C.A.; Bonavia, D.; Dillehay, T.D. Documenting cultural selection pressure changes on chile pepper (Capsicum baccatum L.) seed size through time in Coastal Peru. Econ. Bot. 2014, 68, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naves, E.R.; Scossa, F.; Araújo, W.L.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Fernie, A.R.; Zsögön, A. Heterosis for capsaicinoid accumulation in chili pepper hybrids is dependent on the parent-of-origin effect. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppuluri, L.S.; Krishna, M.S.R. Screening of chilli genotypes for drought tolerance. In New Horizons in Biotechnology; Springer Science+Business Media: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Nsabiyera, V.; Ochwo-Ssemakula, M.; Sseruwagi, P.; Ojiewo, C.O.; Gibson, P. Combining ability for field resistance to disease, fruit yield and yield factors among hot pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes in Uganda. Int. J. Plant Breed. 2013, 7, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, F.D.A.D.; Duarte, S.N.; Medeiros, J.F.D.; Aroucha, E.M.M.; Dias, N.D.S. Quality in the pepper under different fertigation managements and levels of nitrogen and potassium. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2015, 46, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhi, K.; Khader, K.A. Gene effects of fruit yield and leaf curl virus resistance in interspecific crosses of chilli (Capsicum annuum L. and C. frutescens L.). J. Trop. Agric. 2011, 49, 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, O.P.; Dhaliwal, M.S.; Jindal, S.K. Heterosis breeding in chilli pepper by using cytoplasmic male sterile lines for high-yield production with special reference to seed and bioactive compound content under temperature stress regimes. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 262, 109036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, E.M.; Hayes, H.K. Heterozygosis in evolution of life and in plant breeding. Mol. Genet. Genom. 1914, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, R.B. Studies in Indian chillies. The inheritance of some characters in Capsicum annuum (L.). Indian J. Agric. Sci. 1933, 3, 219–300. [Google Scholar]

- Awachar, A.V.; Pandey, M.K. Review on heterosis and combining ability of chilli. Int. J. All Res. Educ. Sci. Methods 2021, 9, 1018–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, A.; Kumar, R.; Solankey, S.S. Estimation of heterosis for yield and quality components in chilli (Capsicum annuum L.). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 12, 6605–6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Jindal, S.K.; Dhaliwal, M.S.; Meena, O.P. Improving fruit traits in chilli pepper through heterosis breeding. J. Breed. Genet. 2017, 49, 26–43. [Google Scholar]

| Crop | Breeding Method | Traits Improved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chilli | Hybridisation of cytoplasmic male sterile lines with potential hybrids | Yield, number of seeds, capsaicin content, quality traits, and bioactive compounds. | [20] |

| Hybridisation of chilli lines with selected testers | Oleoresin content, capsaicin content | [24] | |

| Inter- and intra-specific hybrids developed from the diallel crossing of species of Capsicum, C. chinense, and C. annuum | Capsaicinoid content | [15] | |

| Hybridisation of the genetic male sterile and the cytoplasmic male sterile lines | Total yield, early yield, plant height, fruit length, and a greater fruit number per plant. | [8] | |

| Half-diallel crossing of parental lines | Pericarp thickness, days to 50% flowering, length and width of fruit, seed number per fruit, plant height, total yield, early fruit yield, and weight of 100 seeds. | [25] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hawraa, I.; Khan, M.A.; Akram, M.T.; Rana, R.M.; Tipu, F.A.; Ali, I.; Nawaz, H.; Khan, M.H. Heat Stress in Chillies: Integrating Physiological Responses and Heterosis Breeding Approaches for Enhanced Resilience. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2025, 51, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2025051012

Hawraa I, Khan MA, Akram MT, Rana RM, Tipu FA, Ali I, Nawaz H, Khan MH. Heat Stress in Chillies: Integrating Physiological Responses and Heterosis Breeding Approaches for Enhanced Resilience. Biology and Life Sciences Forum. 2025; 51(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2025051012

Chicago/Turabian StyleHawraa, Inaba, Muhammad Azam Khan, Muhammad Tahir Akram, Rashid Mehmood Rana, Feroz Ahmed Tipu, Israr Ali, Hina Nawaz, and Muhammad Hashir Khan. 2025. "Heat Stress in Chillies: Integrating Physiological Responses and Heterosis Breeding Approaches for Enhanced Resilience" Biology and Life Sciences Forum 51, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2025051012

APA StyleHawraa, I., Khan, M. A., Akram, M. T., Rana, R. M., Tipu, F. A., Ali, I., Nawaz, H., & Khan, M. H. (2025). Heat Stress in Chillies: Integrating Physiological Responses and Heterosis Breeding Approaches for Enhanced Resilience. Biology and Life Sciences Forum, 51(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/blsf2025051012