Reorientation of Methods Applied to Plant Protection as an Effect of Climate Change †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Analysis of Development Areas in Romania

- Protection of plants or plant products against any harmful organism or prevention of these organisms;

- Exercising an action on the vital processes of plants, other than a nutritional action;

- Ensuring the preservation of vegetable products, insofar as these substances or products are not subject to other legal regulations on preservatives;

- Destruction of plant parts, stopping or preventing unwanted plant growth.

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. The Farm to Fork Strategy. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/system/files/2020-05/f2f_action-plan_2020_strategy-info_en.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Communication from the Commission to The European Parliament, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of The Regions. COM/2020/381 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0381 (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Eurostat. Sales of Pesticides by Type of Pesticide. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/product?code=tai02 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Commission Regulation (EC) No. 889/2008 of 5 September 2008 Laying Down Detailed Rules for the Implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No. 834/2007 on Organic Production and Labelling of Organic Products with Regard to Organic Production, Labelling and Control. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 250, 1–84. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/889/oj (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Directive 2009/128/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Establishing a Framework for Community Action to Achieve the Sustainable Use of Pesticides (Text with EEA Relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, 309, 71–86. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/128/oj (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Council Regulation (EC) No. 1234/2007 of 22 October 2007 Establishing a Common Organisation of Agricultural Markets and on Specific Provisions for Certain Agricultural Products. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eur/2007/1234/contents (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market and Repealing Council Directives 79/117/EEC and 91/414/EEC. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, 309, 1–50. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/1107/oj (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Directive 98/8/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 February 1998 Concerning the Placing of Biocidal Products on the Market. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1998, 123, 1–63. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/1998/8/oj (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- In the Action Plan of the Strategy, the Commission Proposed a Revision of the Pesticides Statistics Regulation to Overcome Data Gaps and Reinforce Evidence-Based Policy Making. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Agri-environmental_indicator_-_consumption_of_pesticides (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- European Commission. Legal provisions of COM(2017)587—Member State National Action Plans and on Progress in the Implementation of Directive 2009/128/EC on the Sustainable Use of Pesticides. COM(2017)587. 10 October 2017. Available online: https://www.eumonitor.eu/9353000/1/j4nvhdfcs8bljza_j9vvik7m1c3gyxp/vkicge6lwnwz (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Popescu, L.; Safta, A.S. The Causal Relationship of Agricultural Standards, Climate Change and Greenhouse Gas Recovery. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2021, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, H.L.; Scheelbeek, P.F.; Chalabi, Z.; Green, R.; Smith, R.D.; Haines, A.; Dangour, A.D. Effects of environmental change on agriculture, nutrition and health: A framework with a focus on fruits and vegetables. Wellcome Open Res. 2017, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Second Pillar of the CAP: Rural Development Policy, Brussels. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/110/second-pillar-of-the-cap-rural (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Andrei, J.V.; Dusmanescu, D.; Mieila, M. The influences of the cultural models on agricultural production structures in Romania and some EU-28 countries—A perspective. Econ. Agric. 2015, 62, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Regulation (EC) No. 1185/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2009 Concerning Statistics on Pesticides (Text with EEA Relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, 324, 1–22. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/1185/oj (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- European Commission, Brussels; Directorate General Communication, Media Monitoring & Eurobarometer (COMM.A.3). Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/web/who-is-who/organization/-/organization/COMMU/COM_CRF_231900 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

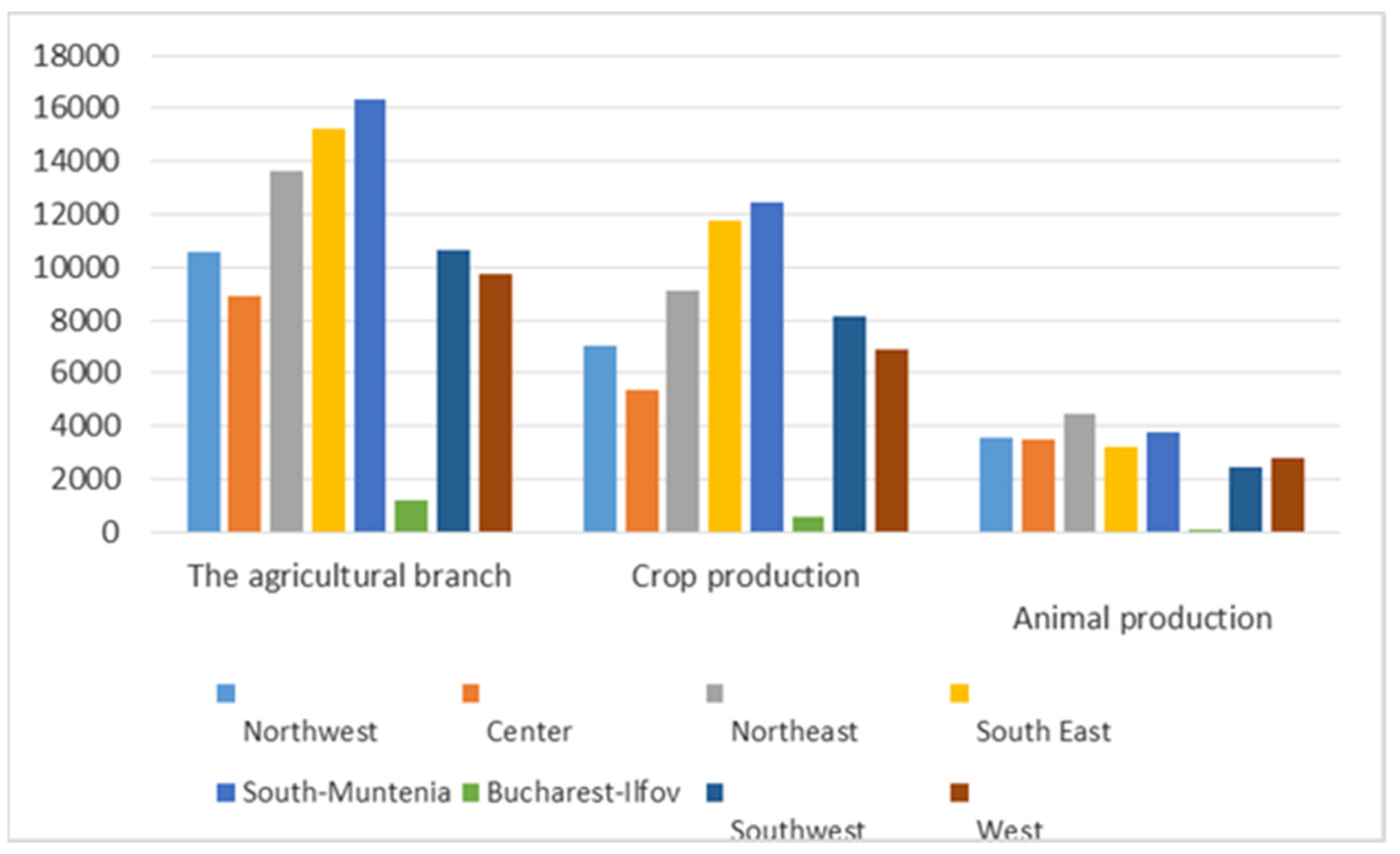

| Item | Northwest | Center | Northeast | South East | South-Muntenia | Bucharest-Ilfov | Southwest | West |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The agricultural branch | 10,561 | 8930 | 13,652 | 15,256 | 16,336 | 1196 | 10,656 | 9762 |

| Crop production | 7015 | 5348 | 9092 | 11,724 | 12,428 | 606 | 8141 | 6862 |

| Animal production | 3523 | 3509 | 4475 | 3239 | 3775 | 110 | 2453 | 2819 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popescu, L.; Safta, A.S. Reorientation of Methods Applied to Plant Protection as an Effect of Climate Change. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2021, 4, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECPS2020-08650

Popescu L, Safta AS. Reorientation of Methods Applied to Plant Protection as an Effect of Climate Change. Biology and Life Sciences Forum. 2021; 4(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECPS2020-08650

Chicago/Turabian StylePopescu, Lavinia, and Adela Sorinela Safta. 2021. "Reorientation of Methods Applied to Plant Protection as an Effect of Climate Change" Biology and Life Sciences Forum 4, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECPS2020-08650

APA StylePopescu, L., & Safta, A. S. (2021). Reorientation of Methods Applied to Plant Protection as an Effect of Climate Change. Biology and Life Sciences Forum, 4(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECPS2020-08650