1. Introduction

The dromedary, without which the great nomadic civilizations could never have existed, occupies a predominant place in the economic and social life of the Saharan communities, which lived in harmony with their environment, yet were characterized by extremely vigorous living conditions. The caravan ensured the transport of goods as well as that of intrepid travelers and pilgrims, hoping to find in the “oasis islands” something to quench their thirst, eat their fill, and recover their strength [

1]. This livestock breeding, long considered a survival of a bygone era, is of definite ecological, economic, social, and cultural interest.

What significance should be attributed to camel breeding in Algeria in the third millennium? Because of its qualities as an ambulatory walker, its legendary sobriety, and its habit of making do with the poor fodder of the desert, the dromedary is the emblematic animal par excellence because of its robustness, productivity, and diligence, it demonstrates all the qualities of a multi-purpose animal. The threshold of the 2000s constitutes a new boom for this animal marked by a new fate of the adopted systems approaching more urban areas via new marketing channels [

2].

It is through this dimension that the present synthesis highlights the scope of camel breeding in the Northern Sahara. The diversity of its populations, the increase in its numbers, and the camel vocations are combined with new systems and give rise to the emergence of camel sectors of commerce. Faced with climate change and food security challenges, Algeria should count on this species as an important part of its national economy.

2. Materials and Methods

The method adopted highlights the camel system approach used in the Algerian Northern Sahara represented by regions of El-Oued, Ouargla, and Ghardaïa. Field surveys involving various stakeholders (camel drivers, producers, traders, and consumers) have made it possible to identify the trajectories and typology of livestock farming systems, their vocations, and the related sectors.

The objective of this study is to situate camel breeding practices.

3. Results and Discussion

Data mining and field investigations have enabled us to establish the following:

3.1. Size of Camels

Over a century, there was a sharp decline in population numbers, dropping from 260,000 heads in 1890 to 113,900 in 1988, while the decade that followed was marked by a jagged trajectory, reaching 154,310 heads in 1998 [

3]. What can we learn from these fluctuations? The lack of interest in this species despite the boom in Saharan regions, but modernism deemed antinomic to dromedary [

4].

At the dawn of the new millennium, a new impetus was given to camel breeding, with the number of camels increasing from 220,000 in 1999 to 435,214 in 2020 [

3]. What can be deduced from this significant increase in the number of camels? The spatiotemporal anchoring of camel herds in and around urban centers as a result of the sedentarization of communities, the birth premium initiated through the National Fund for Agricultural Regulation and Development in 2000, and the increased demand for camel milk seem to be the main causes of the renewed interest in camel farming.

3.2. Specialized Breeding Systems

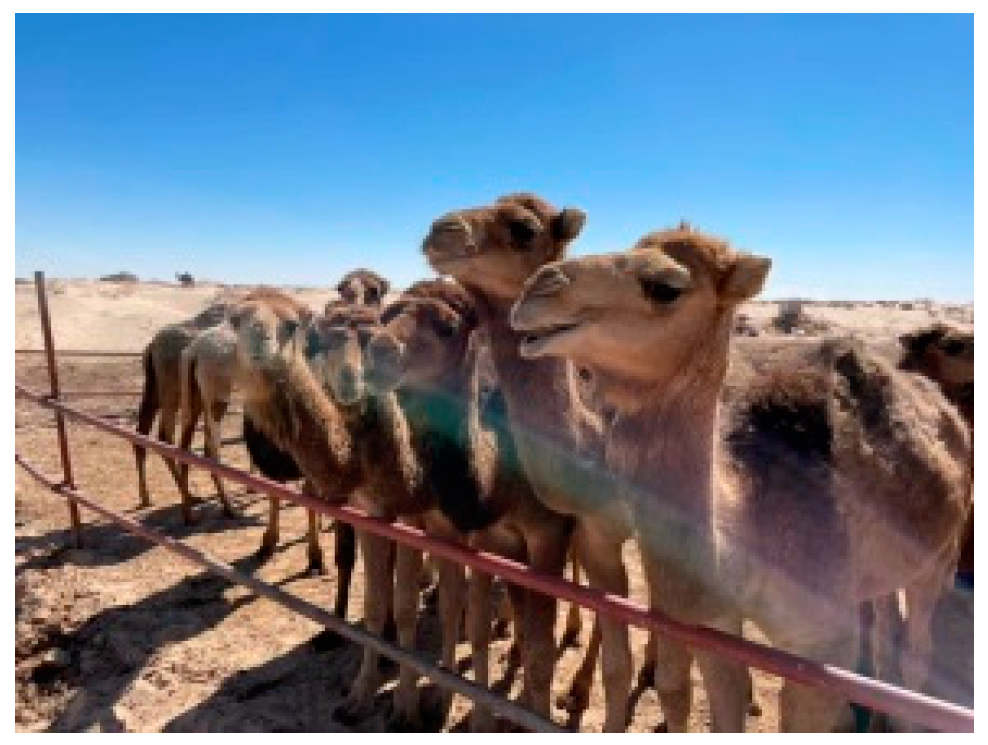

At present, in the Northern Sahara, where camel breeding is proving to be a booming business, reveals that livestock farms depend on a feeding system through which camel breeders adopt three distinct modes: grass-fed (

Figure 1), stall-fed (

Figure 2), or mixed. Each of the systems responds to specific functions, the analysis of which gave rise to four types of livestock farming according to their purpose: (i) dairy type, (ii) meat type, (iii) poly vocational type, and (iv) meharis for socio-cultural and sporting purposes.

3.3. Multi-Purpose Camel

It is through the great string of its products and services that new prospects for the camel sector are opening up. A range of functions could not exist without the presence of this animal, which, thanks to its polyfunctionality, renders enormous services to camel drivers whose lives are intimately linked to the animal [

5]. Consequently, an arrangement of camel breeding to better increase its production can be considered in the immediate future [

6].

3.4. Camel Industry

Many products and by-products made from this animal can foster a real natural industry. Between meat and milk, camel hair is highly sought after for a range of textile products with strong cultural identities. Further, camel skin is also destined to develop a small industry [

7]. Finally, the dung, characterized by a low nitrogen composition but rich in indigestible fibers, is suitable for processing into paper pulp [

8].

3.5. Lucrative Uses

Useful for many functions, the camel is now part of the daily life of Saharan societies thanks to its sporting performances as a racing animal (Méhari), cultural, as a chessboard of festive circumstances (contests and games) and tourist, as a walking tool (

Figure 3).

4. Conclusions

If sedentarization had made it possible to judiciously combine agricultural production and camel breeding by making the most of scarce resources (cultivable space and water points), then this association would be the culmination of a long process that has contributed to the intensification of its components. Validly, camel breeding systems are undergoing profound changes, moving from the grass system (divagation) to mixed systems (transhumant) to industrial forms (intensive), whose cameline sectors are beginning to organize themselves via promoting products with high economic value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.; methodology, A.S., A.A., S.B. and Z.B.; software, A.S., A.A., S.B. and Z.B.; validation, A.S., A.A., S.B. and Z.B.; formal analysis, A.S., A.A., S.B., and Z.B.; investigation, A.A., S.B. and Z.B.; data curation, A.S., A.A., S.B. and Z.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The works consulted are detailed in the bibliography.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Marouf, N. Lecture de l’espace Oasien; FeniXX réédition numérique (Sindbad): Paris, France, 1980; p. 281. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Faye, B.; Senoussi, H.; Jaouad, M. Le dromadaire et l’oasis: Du caravansérail à l’élevage périurbain. Cah. Agric. 2017, 26, 14001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Data. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/fr/#data/QL (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Faye, B.; Bengoumi, M.; Barkat, A. Le développement des systèmes camelins laitiers péri-urbains en Afrique. In Proceedings of the Atelier International sur le lait de Chamelle en Afrique, Niamey, Niger, 5–8 November 2003; FAO-CIRAD KARKARA: Rome, Italy, 2004; pp. 115–125. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- Adamou, A. Note sur la polyfonctionnalité de l’élevage camelin. J. Algér. Rég. Arid. 2009, 8, 108–122. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Saadoud, M.; Nefnouf, F.; Hafaoui, F.Z. La viande cameline dans deux régions du Sud Algérien. Viandes et Produits Carnés 2019. Available online: https://www.viandesetproduitscarnes.fr/index.php/fr/1020-la-viande-cameline-dans-deux-regions-du-sudalgerien (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Senoussi, A. Camel breeding in Algeria: Myth or reality? In Proceedings of the 19èmes Rencontres Autour des Recherches sur les Ruminants, Paris, France, 5–6 December 2012; I.N.R.A.: Paris, France, 2012; p. 308. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- Senoussi, A. Le Camelin; Facteur de la Biodiversité et à Usages Multiples. In Proceedings of the Actes Séminaire International sur la Biodiversité Faunistique en Zones Arides et Semi Arides, Ouargla, Algérie, 20–22 October 2009; Université Kasdi Merbah: Ouargla, Algérie, 2009; pp. 265–273. (In French). [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).