Abstract

The following research was conducted in the Carlos Botelho State Park, São Paulo State, Brazil, to examine the overnight sites of the southern muriqui (Brachyteles arachnoides), an endemic primate of the Atlantic Forest. A multiple factor statistical analysis was carried out to determine the selection of the sleeping areas. Findings indicate that the southern muriqui selects its sleeping sites based on comfort and hygiene factors, favoring body thermoregulation, deterring predators and parasites, and staying near food sources. Brachyteles arachnoides is critically endangered, therefore this work aims to contribute to the ethological and social reconstruction of the southern muriqui, approaching the understanding of its behavior patterns and its possible implications in human species evolution. It also intends to consolidate an understanding from another non-human being to generate a comprehensive view of the ecosystem across human generations that promote biodiversity conservation, based on a harmonious existence among the human primate and the non-human animal.

1. Introduction

Brachyteles arachnoides (southern muriqui) plays a vital role in the Carlos Botelho State Park, such as the dispersing of seeds and the maintenance of structure and regeneration of large parts of the Atlantic Forests [1]. Therefore, the continuous deterioration of their habitat indisputably affects their sleeping sites, which not only serve to recover in a physiological way, as observed in different primates, but could also provide spaces for social relationships that take place during the night [2]. The study and identification of these places is relevant to understand the ethology of primates, to protect this species, as well as to generate educational programs, improve the conservation of the southern muriqui’s developmental spaces and promote sustainable development in the area.

Given that the southern muriqui inhabits an important area of conservation and contributes to the preservation of the Atlantic Forest, this paper seeks to investigate why they seek out specific places as sleeping sites, the factors that affect such selection and to comprehend the evolutionary implications of said options on the lineage of primates. Likewise, it is fundamental to comprehend how said selection could affect social aspects of deprivation of liberty, improving their quality of life.

It should be noted that the present study focuses on the search of utilizing new concepts to understand the otherness in a different manner outside of our own prepositions. The so-called “ontological turn” in anthropology has come to cement the idea that the difference between human and non-human beings is not the soul, but rather the body, hence the shape of bodies would be more than mere physical composition.

Indeed, the body is a conjunction of biological instruments that permits a species to occupy a determined habitat and develop a mode of existence that allows it to better identify itself [3,4,5,6]. These different corporeal definitions bring with them a diversity of perceptions and points of view, as shown by Viveiros de Castro [4] in stating that, if animals perceive humans as predators, it is because their point of view depends on their bodies, which distinguish themselves from our bodies based on the intrinsic dispositions that characterize them.

One way to access this is through the observation techniques of social sciences, such as ethnography and ethology, due to its ability to study and elucidate what is questioned in primatology. That is, to disclose a new other, one that is not only generated purely by its peers, but also, in its relation to human primates, creates a new otherness, a non-human other [7].

2. Materials

2.1. Individuals and Place of Study

The park’s study zone is divided in two: HQ 1 and HQ 2. HQ 1 was used for the development of this paper. The area is the work site for the “Pro-Muriqui Association”, founded in the year 2000 [1], a hunting-free zone.

The space accounts for a group of approximately 50 southern muriquis (Brachyteles arachnoides), which are divided in groups of fission–fusion. Therefore, smaller cliques are generally observed. These primates are habituated to being observed because they have been monitored since the year 1986 [8].

2.2. Selection of Sites

The study was carried out between the months of September and October 2018. The first month consisted of observation through pedestrian walking trails and non-established paths for 12 h daily (6:00 to 18:00), following the trajectories of the southern muriqui with the aid of a local guide from the Pro-Muriqui Association.

During this stage of the investigation, sleeping sites were identified considering the observations made by the officials at the Pro-Muriqui Association for approximately 20 years. Throughout the rounds of the park, the locations and geographical coordinates of a reference tree were registered for each of the 10 most frequented sleeping sites.

During the second month of work, the data collection was deepened pertaining to different ecological variables of interest for the study. These correspond to the presence/absence of lianas within the sleeping sites, presence/absence of slopes, cardinal orientation of the sleeping sites, species of trees present on the site, physiological characteristics of the trees utilized (height of the first branch, maximum height of the tree, leafiness of the crown, height of the branch chosen to spend the night).

3. Data Collection

3.1. Sleeping Sites

The dimensions used to delimit the sleeping sites were established in relation to the largest area used to spend the night, which consists of dimensions approximately 100 × 100 m. In each site, the sleeping trees have a distance of 50 m from each other. Geographical barriers were considered for inter-site differentiation. The geographical coordinates of the grid were taken through a GPS Garmin GpsMap 64 sx, to then proceed to the physical description of the site, considering the geographical orientation of the slope (if one is found there) with a compass.

3.2. Variables of the Sleeping Trees

A GPS Garmin GpsMap 64 sx was utilized to mark the coordinates of each sleeping tree within the sites. The common and scientific name of each tree was recorded to observe any preference for a specific species in contrast to the environmental offering of species present on the site.

Finally, the following variables of each sleeping tree per site were registered, following the parameters utilized by Liu and Zhao [9]:

- Height of the tree: A Nikon Laser Forestry Pro altimeter was used to measure the height from floor to crown.

- Height of the first branch: The height of the first branch was measured using a Nikon Laser Forestry Pro altimeter.

- Density of crown: 1: very leafy; 2: can be seen through them; 3: very few leaves.

- The location of the branch chosen by the muriquis was measured in relation to the crown: Close to the crown (≤3 m), middle of the crown (>3 m and <6 m), and far from the crown (≥6 m).

3.3. Presence of Predators

The presence of escape routes and proximity between trees was observed. The presence of marks left by possible predators was also taken into account, such as jaguars (Panthera onca, Puma concolor) and birds of prey (Spizaetus tyrannus), inside the Carlos Botelho State Park [10].

3.4. Climatic Conditions

The daily temperature was recorded in Celsius with a thermometer located in the forest. Likewise, the levels of precipitation were registered with the use of a pluviometer as well as the period of use of the site (dry days–rainy days).

3.5. Proximity to Food

To this end, 20 trees within each quadrant that were taken advantage of by the southern muriqui after their feedings were sought. Later, each tree species was identified using routed ribbons placed by the workers of the Pro-Muriqui Association as basis of a large trajectory of observation and previous knowledge of each species.

In a first instance of analysis, frequency tables were created to organize, summarize and distribute the data by frequency, in addition to obtaining the variables of mode and mean.

In the case of the variables of precipitation (P) and temperature (T°) of the sites that make up the samples, a variance analysis or ANOVA analysis was made.

4. Results

A topographical height range in which the sleeping sites were located was established, one that fluctuates between 721,707 m.s.n.m. and 743,79 m.s.n.m. Meanwhile, the presence of slopes is notable within all sites, with a preference for those oriented towards the southeast and, in addition, the proximity of the study sites to rivers is relevant at 90% of the studied sites. On the other hand, it is noted that out of all 10 sites, only one has lianas.

In 70% of the sites, there is less than ten meters between trees, and the remaining 30% of trees have close connections to each other through the proximity of their branches. It is also worth noting the presence of ferns at ground level in 8 out of 10 sites.

As far as the utilization of the site’s sleeping trees, there is an observable fluctuation between one and six trees per site, with an average frequency of two trees per sleeping site.

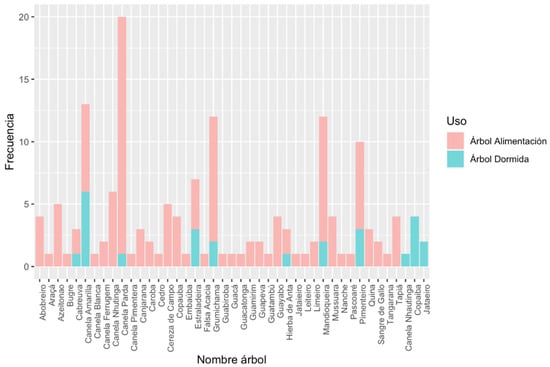

4.1. Tree Species

A total of 226 trees within the 10 observed sites were registered, which correspond to trees meant for sleeping and for feeding. Of these, only 40 species were recognized along with their genus. Likewise, the diversity of trees used for sleeping is less than the ones used for feeding. The most frequently used species for sleeping was the yellow cinnamon (Ocotea catharinensis Mez), while brown cinnamon (Ocotea spixiana (Nees) Mez) was the species most used for feeding.

4.2. Sleeping Tree Variables

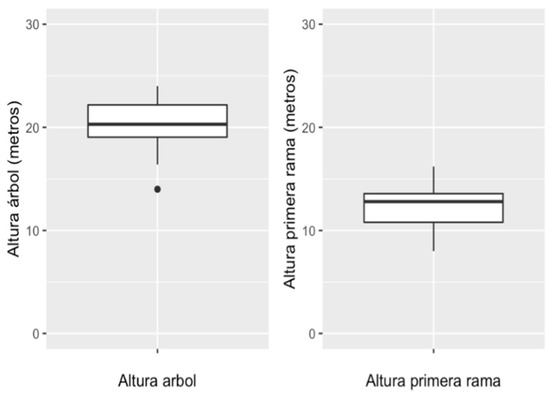

Regarding the measurements registered on the height of sleeping trees (n = 26), we can observe that the height of trees used by the muriquis varies between 19.05 and 22.18 m. The measurements registered on the height of the first branch of the trees used for sleep have a median of 12.34 m, with a standard deviation of 2.05 m. A preference on the height of the first branch is noted to be between 10.80 and 13.57 m.

An observable preference on the part of the muriquis is for crowns that are mildly dense, in other words, that are see-through, corresponding to 61.5% of selected trees (Table 1). Plus, a 38.5% registry of trees with low density crowns.

Table 1.

Density of the sleeping tree’s crowns.

Regarding the location of the sleeping branch, we can observe that of the 26 trees registered, the total of the observed individuals presents a selection preference for a location of the sleeping branch less than 3 m from the treetop (height maximum) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Location of sleeping branch in sleeping trees.

4.3. Climatic Conditions

Regarding the variables of temperature and rainfall, an ANOVA test was carried out to identify if whether climatic factors have an impact on the selection of sleeping sites. For rainfall, a p value of 0.322 was observed and for temperature a p value of 0.138, indicating that there are no significant differences between the sites due to climate factors. These values would indicate a low or no significance in the selection of sleeping sites.

5. Discussion

5.1. Choice of Sleeping Places Based on Comfort and Hygiene

The advantages presented around the adaptive processes indicate that Brachyteles arachnoides selects its sleeping sites mainly based on comfort and hygiene. This focuses on the factors that generate the well-being and physiological satisfaction of the individual, in this case the B. arachnoides [2]. This selection would be made based on the choice of specific trees (Figure 1) located in a topography represented by slopes of evergreen forest with a preference of cardinal southeast orientation, with nearby trees for food and various plant strata both for displacement and for spending the night.

Figure 1.

Frequencies of feeding and sleeping trees.

This selection shows us that the southern muriqui follows certain “patterns” that would imply the delivery of adaptive advantages, contributing to the opening of social development, the displacement of primates and increasing ecological efficiency in the face of available resources [2,11]. However, not all the factors are direct players in the selection of the sleeping site, since the temperature is not important for the selection in these primates, probably due to small variability of temperature and annual rainfall of the Atlantic Forest [12].

5.2. Social Aspects of Choosing Sleeping Places

Within the life histories of these primates, the repetition of these selection patterns leads to the generation of attachment to the physical spaces where they develop [13]. This can not only be seen in territorial defense behaviors, or in compliance with the hypothesis of comfort, understanding that there is a necessary calm to be able to live, but it can also be observed in the modification of these spaces, such as the dispersal of primates in the trees to generate beds with greater comfort.

Along with the concept of territory, it is also possible to visualize a configuration on a smaller scale that remains constant in the selection of sleeping and foraging spaces of the southern muriquis. This is made up of the selected characteristics of each site (see Table 1 and Table 2, Figure 1 and Figure 2), in which the animals find rest and safety in the community, so it will be named with the concept of “home”. This physical space called home highlights the ability of primates to socialize, since it provides well-being in the face of environmental pressures and responds to a certain collective memory in the selection and recurrent use of spaces both to spend the night and to partake in their daily activities [14,15].

Figure 2.

Height of sleeping trees and height of first branch of sleeping tree.

This allows us to reflect on the way in which the muriqui creates its own identity in the logic of inclusion/exclusion of the other to generate community ties that will last over time. This exercise of creating otherness highlights how the concept of identity group or home is indivisible to the concept of territory, since both are jointly constructed in logics of inclusion, exclusion, and memory to allow the harmonious development of the muriqui groups along the Atlantic Forest [16].

The concepts presented above become extremely relevant in the current context, where the capitalist depredation of the environment has generated the irreparable destruction of a large part of the ecological niches used by neotropical primates [17]. One way to reduce the negative effects of animal captivity is by rescuing the ethological needs of wildlife that contribute to long-term well-being.

However, this is interrupted by the hierarchical opposition between human and non-human animals [18,19], making the latter’s own perspectives and interactions invisible, such as specific cultural and social qualities of each species, as well as the potentiality of agency and change on the material reality they inhabit.

These biases are observed, specifically, in spaces of animal captivity in which, when entering or being born in these spaces, the primate is limited to understanding what is presented by humans as a social and territorial space suitable for other species [19]. The main problem of the above is the eradication of the evolutionary memory present in each species, causing a conditioning that limits the optimal development of the life of the individuals and future generations present in these contexts.

6. Conclusions

We can establish that there is a preference for sites that present similar characteristics, which correspond to the height of the first branch, height of the tree, density of the treetops, presence of river, distance between trees and tree species.

- Regarding the tree species that appeared in the sleeping sites, it was possible to identify a diversity of 43 species, which were used both for spending the night and for their food.

- The trees used for sleeping presented a standard height of 20 m, the height of the first branch of the tree presented an average of 12.34 m. In turn, the selected trees mostly had a top in which you could see through it. As for the “sleeping bed”, it was presented with a height of no less than 3 m from the top of the tree.

- The sleeping sites were located at heights between 700 and 800 m above sea level. Most of them were ferns on the ground and constantly moving water courses. All the sites were located on slopes and had the immediate presence of feeding trees. Of the total of the sites, three were reused for a maximum of two days and no presence of other primates were observed within the same sleeping site.

Among the reflections that derive from this work, it is important to highlight that this knowledge from the behavioral ecology of Brachyteles arachnoides leads us to generate a comprehensive notion about its life model. At the same time, it allows data to be delivered to achieve a comprehensive conservation of the biotic and abiotic components that are part of the sleeping sites selected by the southern muriqui within the Atlantic Forest. Understanding that the ecosystem is highly fragmented and threatened due to the presence of agriculture and logging, among other factors, which makes the evolutionary development and conservation of individuals immensely difficult.

A contribution to remedy this problem can be made from the academic field, since it is through research that we can increase the knowledge that we have of what is foreign to us, allowing us to expand horizons towards the creation of new urban realities free from a capitalist and extractivist perspective. This perspective, which we once lacked, allowed relationships between organisms to form a harmonious space where both realities converge for a horizontal coexistence.

That is why it is essential to capture this understanding from a non-human other in the educational field, to generate a comprehensive vision of the ecosystem across human generations that promote the conservation of biodiversity and a harmonious existence with the world around them.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The realization of this study was thanks to the willingness of the Muriqui Association to receive me in its research center. I am very grateful to Miriam Perez De los Rios, René Bobe, Mauricio Talebi, and Catalina Garnham Brunel for their research recommendations, and Gabriel Castro Hebel, Vicente Vásquez Canales and Louise Regina Aguiar for your help with my English.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyzes, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Talebi, M.; Soares, P. Conservation research on the southern muriqui (Brachyteles arachnoides) in São Paulo State, Brasil. Neotrop. Primates 2005, 13, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R. Ethology and ecology of sleep in monkeys and apes. Adv. Study Behav. 1984, 14, 165–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, E.V. Perspectivismo y Multinaturalismo en la América Indígena. In Racionalidad y Discurso Mítico, 1st ed.; De Olivos, M., Ed.; Imprenta Nacional de Colombia; Centro Editorial Universidad del Rosario: Bogotá, Colombia, 2003; pp. 191–224. [Google Scholar]

- de Castro, E.V. Introducción al perspectivismo amerindio. In La Mirada del Jaguar, 1st ed.; Tennina, L., Bracony, A., Sburlatti, S., Eds.; Tinta Limón Ediciones: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2013; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on livelihood, Dwelling and Skill, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Group; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 1–480. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, P. Más Allá de Naturaleza y Cultura, 1st ed.; Pons, H., Ed.; Amorrortu: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012; pp. 1–619. [Google Scholar]

- Rapchan, E.S.; Neves, W.A. Primatologia, culturas não humanas e novas alteridades. Sci. Studia 2014, 12, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M. Estimativa Populacional de Muriquis-do-sul (Brachyteles arachnoides, PRIMATES, É. Geoffroy 1806) e Avaliacão da caca no Parque Estadual Carlos Botelho, Continuum Ecológico de Paranapiacaba, São Paulo. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.H.; Zhao, Q.K. Sleeping sites of Rhinopithecus bieti at Mt. Fuhe, Yunnan. Primates 2004, 45, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, P.; De Carvalho, O.; Strier, K. Population variation in patch and party size in muriquis (Brachyteles arachnoides). Int. J. Primatol. 1998, 19, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosheleff, V.P.; Anderson, C.N. Temperature’s influence on the activity budget, terrestriality, and sun exposure of chimpanzees in the Budongo Forest, Uganda. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2009, 139, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morellato, L.P.C.; Haddad, C.F. Introduction: The Brazilian Atlantic Forest 1. Biotropica 2000, 32, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinbergen, N. The functions of territory. Bird Study 1957, 4, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, M. Escolha de árvore e sítio de dormir e sua influencia na rota diária de um grupo de Cebus nigritus, no Parque Estadual Carlos Botelho, SP. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sarges, K.L. Cognição Espacial de muriquis-do-norte (Brachyteles hypoxanthus—Primates, Atelidae). Masters Thesis, Universidad Federal Do Espírito Santo, Espírito Santo, Brasil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa, G. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 1st ed.; Capitán Swing: Andalucía, España, 1987; pp. 1–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, G.; Ortega-Baes, P. La Sexta Extinción: La Pérdida de Especies y Poblaciones en el Neotrópico. Conservación Biológica: Perspectivas de Latinoamérica, 1st ed.; Simonetti, J.Y., Dirzo, R., Eds.; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 2011; pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D.; Ishikawa, N.; Gilbert, S.F.; Olwig, K.; Tsing, A.L.; Bubandt, N. Anthropologists are talking–about the Anthropocene. Ethnos 2016, 81, 535–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañalich, J.P. Animalidad y subjetividad. Los animales (no humanos) como sujetos-de-derecho. Rev. Derecho (Valdivia) 2018, 31, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).