HIV Prevention Practices Among South African University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

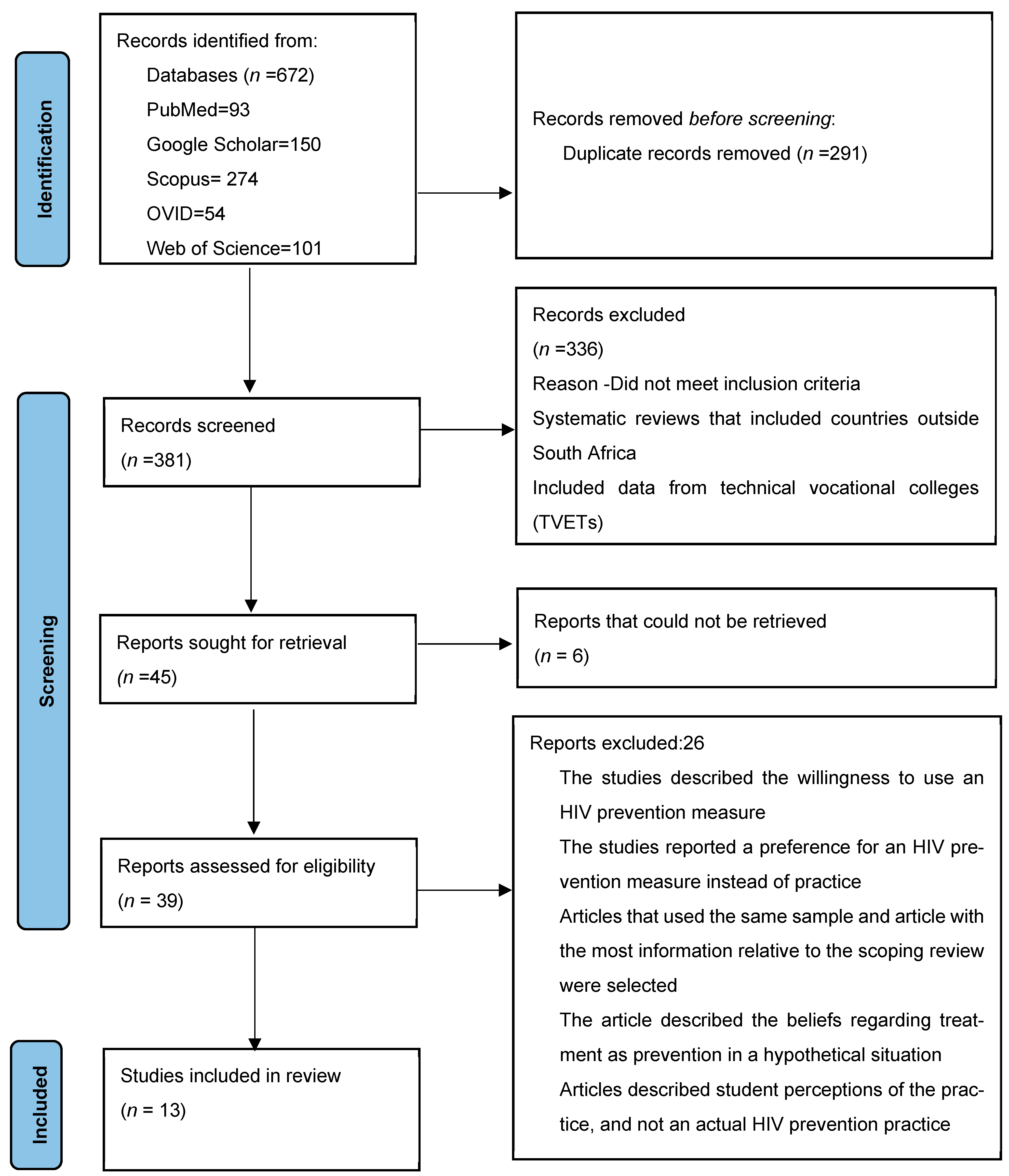

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Assessment of Risk of Bias

2.2. Consultation

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Results from the Risk of Bias Assessment

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies Included

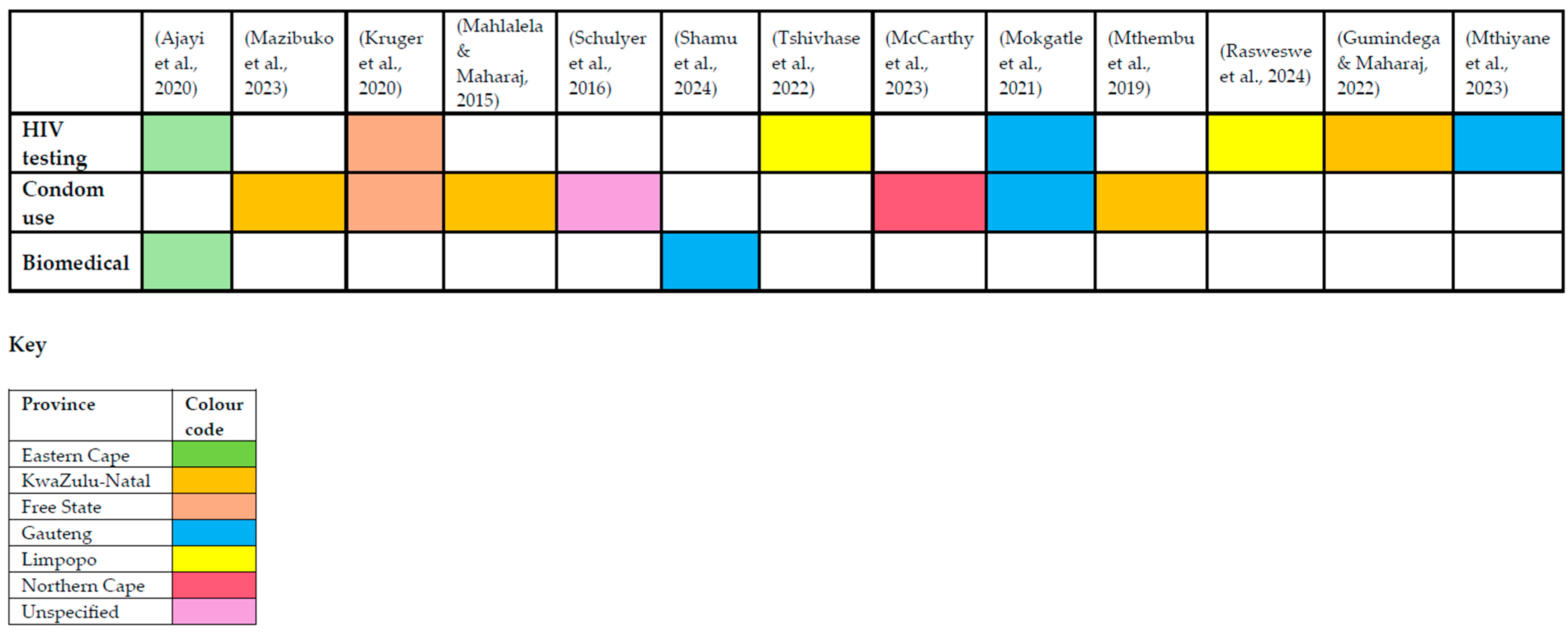

3.3. What Are the HIV Prevention Measures Used by University Students in South Africa?

3.4. HIV Testing

3.5. Male and Female Condom Use

3.6. Biomedical HIV Prevention Measures (PEP and PrEP)

3.7. Findings from the Consultation

Sample Demographic Characteristics

3.8. Emerging Themes from the Consultation: HIV Prevention Practices

3.9. Theme 1: Regular HIV Testing, Which Includes HIV Self-Testing

“I’ve been tested about two to three times this year”(P2, 20-year-old female, nursing student)

“Yes, I get tested, but I don’t know how often I don’t count, but I do get tested”(P3, 19-year-old female, natural sciences student)

“I have been tested [for HIV] once”(P6, 22-year-old, male nursing student)

“I’ve been tested twice since I started university… It’s the stigma that makes me scared of testing because other students are going to talk about it…. I fear being seen by others and judged for getting tested… They should give us more places where we can test privately”(P1, 22-year-old, female, social sciences student)

“I get tested once a year; …the university should make HIV self-testing kits available”(P14, 22-year-old, male, education student)

3.10. Theme 2: Condom Use for HIV Prevention

“I feel comfortable about using condoms because they prevent pregnancy, and they prevent other diseases such as STIs”(P4, 22-year-old, female, social sciences student)

“I always use a condom…I have always stood my ground and insisted on using protection.”(P14, 22-year-old male, education student)

“I use condoms and sometimes I consider abstaining if I don’t feel safe, … However, sometimes you feel you can trust your partner, or you can be too shy to insist on using protection”(P1, 22-year-old, female, social sciences student)

“Yes, I use condoms, but there are situations in which I may not prevent HIV. Because if I know the health status of that partner, that can be possible, that I won’t use a condom, because we trust each other and know each other’s health status [results from HIV test]”(P9, 22-year-old, male, nursing student)

“Yeah, there are situations where HIV prevention methods, like condoms, may not be used… it depends on… but I cannot guarantee maybe out of 100 I would give 50% if you know that you have one partner, you will not use them.”(P6, 22-year-old, male nursing student)

“Yes, I stay safe by using condoms, regular testing, and being in a monogamous relationship”(P14, 22-year-old male, education student)

3.11. Theme 3: Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Used with Other HIV Prevention Measures

“Yes, I have been tested about four times this year, and I have also used PrEP.”(P7, 19-year-old, male, nursing student)

Participant P13 also noted how they protected themselves from HIV using a combination of HIV testing, PrEP, and condom use.

“Using condoms, taking PrEP, and getting regularly tested”.(P13, 20-year-old, female, natural sciences student)

“I also use prevention tools like PrEP and self-test kits ought to be more affordable and available”(P15, 22-year-old, female, social work student)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Significance and Implications

5.2. Strengths and Limitations

5.3. Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| PrEP | Pre-exposure Prophylaxis |

| PEP | Post-Exposure Prophylaxis |

| U=U | Undetectable=Untransmissible |

| VMMC | Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision |

| MSM | Men who have Sex with Men |

| PLWH | People living with HIV |

| UNAIDS | Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

| DREAMS | Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-Free, Mentored, and Safe women |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| PCC | Population Concept Context |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| STI | Sexually Transmitted Infections |

References

- Adeagbo, O. A., Seeley, J., Gumede, D., Xulu, S., Dlamini, N., Luthuli, M., Dreyer, J., Herbst, C., Cowan, F., Chimbindi, N., Hatzold, K., Okesola, N., Johnson, C., Harling, G., Subedar, H., Sherr, L., McGrath, N., Corbett, L., & Shahmanesh, M. (2022). Process evaluation of peer-to-peer delivery of HIV self-testing and sexual health information to support HIV prevention among youth in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Qualitative analysis. BMJ Open, 12(2), e048780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, A. I., Ismail, K. O., & Akpan, W. (2019). Factors associated with consistent condom use: A cross-sectional survey of two Nigerian universities. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajayi, A. I., Yusuf, M. S., Mudefi, E., Adeniyi, O. V., Rala, N., & Goon, D. T. (2020). Low awareness and use of post-exposure prophylaxis among adolescents and young adults in South Africa: Implications for the prevention of new HIV infections. African Journal of AIDS Research, 19(3), 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amevor, E., & Tarkang, E. (2022). Determinants of female condom use among female tertiary students in the Hohoe municipality of Ghana using the health belief model. African Health Sciences, 22(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckham, S. W., Crossnohere, N. L., Gross, M., & Bridges, J. F. P. (2020). Eliciting preferences for HIV prevention technologies: A systematic review. The Patient, 14(2), 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotherton, M. (2025). The cautionary tale of USAID cuts: Resources for HIV treatment and prevention programmes. South African Journal of Bioethics and Law, 18(1), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, V., & Skinner, C. (2008). The health belief model. In K. Glanz, B. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behaviour and health education: Theory research and practice (4th ed., pp. 45–68). Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2014). Thematic analysis. In Encyclopedia of critical psychology (pp. 1947–1952). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2023a). CASP-qualitative studies. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2023b). CASP-cross-sectional studies. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Govender, R. D., Hashim, M. J., Khan, M. A., Mustafa, H., & Khan, G. (2021). Global epidemiology of HIV/AIDS: A resurgence in North America and Europe. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 11(3), 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumindega, G. C., & Maharaj, P. (2022). Challenges with couples HIV counselling and testing among black MSM students: Perspectives of university students in Durban, South Africa. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 19(1), 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higher Health. (2024). Higher health—Improving wellbeing inspiring success. Higher Health. Available online: https://higherhealth.ac.za/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Izudi, J., Okello, G., Semakula, D., & Bajunirwe, F. (2022). Low condom use at the last sexual intercourse among university students in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 17(8), e0272692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L. F., Meyer-Rath, G., Dorrington, R. E., Puren, A., Seathlodi, T., Zuma, K., & Feizzadeh, A. (2022). The effect of HIV programs in South Africa on national HIV incidence trends, 2000–2019. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 90(2), 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. (2021). Global AIDS strategy 2021–2026 end inequalities end AIDS. UNAIDS. [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. (2025, April 22). Impact of US funding cuts on HIV programmes in South Africa. UNAIDS. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2025/april/20250422_southafrica (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Joshi, K., Lessler, J., Olawore, O., Loevinsohn, G., Bushey, S., Tobian, A. A. R., & Grabowski, M. K. (2021). Declining HIV incidence in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis of empiric data. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 24(10), e25818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, R., Alradie-Mohamed, A., Ferdous, N., Vinnakota, D., Arafat, S. M. Y., & Mahmud, I. (2022). Exploring women’s decision-making power and HIV/AIDS prevention practices in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 16626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinheksel, A. J., Rockich-Winston, N., Tawfik, H., & Wyatt, T. R. (2020). Demystifying content analysis. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(1), 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohnert, D. (2025). AID in retreat: The impact of US and European AID cuts on Sub-Saharan Africa. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, W., Lebesa, N., Lephalo, K., Mahlangu, D., Mkhosana, M., Molise, M., Segopa, P., & Joubert, G. (2020). HIV-prevention measures on a university campus in South Africa–perceptions, practices and needs of undergraduate medical students. African Journal of AIDS Research, 19(2), 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y., Wen, Z., Shi, M., Zou, H., & Sun, C. (2025). Biomedical interventions for HIV prevention and control: Beyond vaccination. Viruses, 17(6), 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlalela, N. B., & Maharaj, P. (2015). Factors facilitating and inhibiting the use of female condoms among female university students in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 20(5), 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, S. M., Feitosa, V. R., & Magalhaes, T. M. (2023). Vista do scoping protocol review: PRISMA-ScR guide refinement. The Revista de Enfermagem da UFPI, 12(1), e3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazibuko, N. E., Saruchera, M., & Okonji, E. F. (2023). A qualitative exploration of factors influencing non-use of sexual reproductive health services among university students in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, D., Felix, R. T., & Crowley, T. (2023). Personal factors influencing female students’ condom use at a higher education institution. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine, 16(1), a4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMann, N., & Trout, K. E. (2021). Assessing the knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding sexually transmitted infections among college students in a rural Midwest setting. Journal of Community Health, 46(1), 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlangeni, N., Adetokunboh, O., Lembani, M., Malotle, M., Ngah, V., & Nyasulu, P. S. (2023). Provision of HIV prevention and care services to farmworkers in sub-Saharan African countries. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 28(9), 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokgatle, M. M., Madiba, S., & Cele, L. (2021). A comparative analysis of risky sexual behaviors, self-reported sexually transmitted infections, knowledge of symptoms and partner notification practices among male and female university students in Pretoria, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthembu, Z., Maharaj, P., & Rademeyer, S. (2019). “I am aware of the risks, I am not changing my behaviour”: Risky sexual behaviour of university students in a high-HIV context. African Journal of AIDS Research, 18(3), 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthiyane, H. R., Makatini, Z., Tsukulu, R., Jeena, R., Mutloane, M., Giddings, D., Mahlangu, S., Likotsi, P., Majavie, L., Druker, T., & Treurnicht, F. (2023). HIV self-testing: A cross-sectional survey conducted among students at a tertiary institution in Johannesburg, South Africa in 2020. Journal of Public Health in Africa, 14(5), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukora-Mutseyekwa, F., Mundagowa, P. T., Kangwende, R. A., Murapa, T., Tirivavi, M., Mukuwapasi, W., Tozivepi, S. N., Uzande, C., Mutibura, Q., Chadambuka, E. M., & Machinga, M. (2022). Implementation of a campus-based and peer-delivered HIV self-testing intervention to improve the uptake of HIV testing services among university students in Zimbabwe: The SAYS initiative. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murwira, T. S., Khoza, L. B., Mabunda, J. T., Maputle, S. M., Mpeta, M., & Nunu, W. N. (2021). Knowledge of Students regarding HIV/AIDS at a Rural University in South Africa. The Open AIDS Journal, 15(1), 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musakwa, N. O., Bor, J., Nattey, C., Lönnermark, E., Nyasulu, P., Long, L., & Evans, D. (2021). Perceived barriers to the uptake of health services among first-year university students in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS ONE, 16(1), e0245427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwanri, L., Wamai, R., Teffo, M. E., & Mokgatle, M. M. (2023). Assessing condom use and views on HIV counselling and testing among TVET college students in Limpopo Province, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeagu, E. I., Obeagu, G. U., Ede, M. O., Odo, E. O., & Buhari, H. A. (2023). Translation of HIV/AIDS knowledge into behavior change among secondary school adolescents in Uganda A review. Medicine, 102(49), E36599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odii, I. O., Byun, J. Y., Vance, D. E., Chipalo, E., & Lambert, C. C. (2024). Knowledge, attitudes, and utilization of HIV PrEP among black college students in the United States: A systematic review. Texila International Journal of Public Health, 12(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, G., Adebisi, Y. A., Olarewaju, O. A., Agboola, P., Ilesanmi, E. A., Micheal, A. I., Ahmadi, A., & III, D. E. L.-P. (2021). Understanding female condom use, acceptance, accessibility, awareness and knowledge among female public health students in a Nigerian university: A cross-sectional study. Razi International Medical Journal, 1(2), 1–8. Available online: https://rimj.org/pubs/index.php/journal/article/view/16 (accessed on 25 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Ansah, F. E., Addae, A. A., Amoah, C., Raman, A. A., Adjei, V. D., & Ohenewa, E. (2023). Knowledge and sexual behaviors: A path towards HIV/AIDS prevention among university students. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 27(9), 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasweswe, M. M., Bopape, M. A., & Ntho, T. A. (2024). HIV voluntary counselling and testing utilisation among school of healthcare sciences undergraduate students at the university of Limpopo. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(2), 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautenbach, S. P., Whittles, L. K., Meyer-Rath, G., Jamieson, L., Chidarikire, T., Johnson, L. F., & Imai-Eaton, J. W. (2024). Future HIV epidemic trajectories in South Africa and projected long-term consequences of reductions in general population HIV testing: A mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Public Health, 9(4), e218–e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risher, K. A., Cori, A., Reniers, G., Marston, M., Calvert, C., Crampin, A., Dadirai, T., Dube, A., Gregson, S., Herbst, K., Lutalo, T., Moorhouse, L., Mtenga, B., Nabukalu, D., Newton, R., Price, A. J., Tlhajoane, M., Todd, J., Tomlin, K., … Eaton, J. W. (2021). Age patterns of HIV incidence in eastern and southern Africa: A modelling analysis of observational population-based cohort studies. The Lancet HIV, 8(7), e429–e439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M. J. d. O., Ferreira, E. M. S., & Ferreira, M. C. (2024). Predictors of condom use among college students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(4), 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuyler, A. C., Masvawure, T. B., Smit, J. A., Beksinska, M., Mabude, Z., Ngoloyi, C., & Mantell, J. E. (2016). Building young women’s knowledge and skills in female condom use: Lessons learned from a South African intervention. Health Education Research, 31(2), 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamu, P., Mullick, S., & Christofides, N. J. (2024). Perceptions of the attributes of new long-acting HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis formulations compared with a daily, oral dose among South African young women: A qualitative study. AIDS Care—Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 36(12), 1815–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitindi, G. W., Millanzi, W. C., & Herman, P. Z. (2023). Perceived motivators, knowledge, attitude, self-reported and intentional practice of female condom use among female students in higher training institutions in Dodoma, Tanzania. Contraception and Reproductive Medicine, 8(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simbayi, L., & Zungu, N. (2017). The fifth South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey, 2017 (SABSSM V). Human Sciences Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Tshivhase, S. E., Makuya, T., & Takalani, F. J. (2022). Understanding reasons for low HIV testing services uptake among tertiary students in university in South Africa. HIV & AIDS Review. International Journal of HIV-Related Problems, 21(1), 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandormael, A., Akullian, A., Siedner, M., de Oliveira, T., Bärnighausen, T., & Tanser, F. (2019). Declines in HIV incidence among men and women in a South African population-based cohort. Nature Communications, 10(1), 5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter Sisulu University. (2025). WSU overview. Walter Sisulu University. Available online: https://www.wsu.ac.za/index.php/en/home/discovery-wsu/overview (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2024). Consolidated guidelines on differentiated HIV testing services. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240096394 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2025). Global HIV programme—HIV data and statistics. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/hiv/strategic-information/hiv-data-and-statistics (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- World Medical Association. (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R., Liu, C., Tan, S., Li, J., Simoni, J. M., Turner, D. A., Nelson, L. R. E., Vermund, S. H., Wang, N., & Qian, H. Z. (2021). Factors associated with past HIV testing among men who have sex with men attending university in China: A cross-sectional study. Sexual Health, 18(1), 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuma, K., Simbayi, L., Zungu, N., Moyo, S., Marinda, E., Jooste, S., North, A., Nadol, P., Aynalem, G., Igumbor, E., Dietrich, C., Sigida, S., Chibi, B., Makola, L., Kondlo, L., Porter, S., & Ramlagan, S. (2022). The HIV Epidemic in South Africa: Key findings from 2017 national population-based survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 8125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Year) | Province of Origin | Study Design | Objective | Sample Size | Study Outcomes | HIV Prevention Measures Practised |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ajayi et al., 2020) | Eastern Cape | Descriptive cross-sectional study | To describe levels of PEP awareness and its use among university students. | 772 | There was low PEP awareness among university students. | PEP use HIV testing |

| (Kruger et al., 2020) | Free State | Descriptive cross-sectional study | To assess the practices, perceptions, and needs of undergraduate medical students for HIV-prevention measures. | 470 | 14.2% of students had used an HIV prevention measure | HIV testing Male and female condom use |

| (Mahlalela & Maharaj, 2015) | KwaZulu-Nata | Qualitative study | To describe barriers and facilitators to female condom use among university students | 15 | Facilitators of condom use included dual protection, greater autonomy to initiate safe sex | Female condom use |

| (Mthiyane et al., 2023) | Gauteng | Cross-sectional study | To assess knowledge, attitudes, and practices on HIV self-testing among students at a university | 227 | HIV self-testing among university students is low, with 15% self-testing | HIV self-testing |

| (Schuyler et al., 2016) | Not specified | Qualitative study | To explore whether training on partner negotiation and female condom use affected female condom use among female university students | 39 | Women applied the information learnt to negotiate female condom use. Insertion of the female condom became easier with practice | Use of female condoms |

| (Mazibuko et al., 2023) | KwaZulu-Natal | Qualitative study | To explore factors influencing non-use of sexual and reproductive health services at Mangosuthu University of Technology | 20 | Themes identified include perceived quality of condom use, risky sexual behaviours, drug and alcohol use, and perceived health education received. | Condom use |

| (McCarthy et al., 2023) | Northern Cape | Descriptive cross-sectional study | To assess personal factors that influence condom use among students at a higher education institution in South Africa | 385 | 64.9% of students used condoms. | Condom use |

| (Mokgatle et al., 2021) | Gauteng | Descriptive cross-sectional study | To assess the self-reported partner notification practices, STIs, intentions to notify, and notification preferences among university students | 918 | The odds of delivering an STI notification slip to a former sexual partner were not statistically significant. | HIV testing Female condom use |

| (Mthembu et al., 2019) | KwaZulu-Natal | Qualitative study | To explore risky sexual behaviours among university students | 20 | Students use condoms for HIV prevention, however there is inconsistent use. Most students do not use condoms during first sexual encounter due to lack of preparedness | Condom use |

| (Rasweswe et al., 2024) | Limpopo | Descriptive cross-sectional study | To describe HIV voluntary counselling and testing utilisation among university students | 324 | 65.8% of students used voluntary counselling and testing services | HIV testing |

| (Shamu et al., 2024) | Gauteng | Qualitative study | To explore young women’s preference and willingness to use PrEP | 22 | Students least preferred using the Dapivirine vaginal ring, and some had used oral PrEP; however, discontinued due to busy schedules. | Use of PrEP |

| (Gumindega & Maharaj, 2022) | KwaZulu-Natal | Qualitative study | To explore factors that inhibit couples’ HIV testing and counselling among MSM at a university | 15 | Barriers to HIV testing were homophobia at testing centres, trust assumptions of sexual partners and participants used alternative means such as HIV self-testing | HIV testing |

| (Tshivhase et al., 2022) | Limpopo | Descriptive Cross-sectional study | To determine factors contributing to low HIV testing service uptake among university students | 306 | 44% of students used HIV testing services. Barriers to HIV testing were fear of a positive result, negative attitudes towards health workers, and HIV related stigma | HIV testing |

| Participant | Age | Gender | Field of Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 22 | Female | Social Science |

| P2 | 20 | Female | Nursing |

| P3 | 19 | Female | Natural Science |

| P4 | 22 | Female | Social Science |

| P5 | 19 | Male | Education |

| P6 | 22 | Male | Nursing |

| P7 | 19 | Male | Nursing |

| P8 | 20 | Male | Orthotics and Prosthetics |

| P9 | 22 | Male | Nursing |

| P10 | 21 | Male | Internal Auditing |

| P11 | 19 | Female | Social sciences |

| P12 | 22 | Female | Natural Science |

| P13 | 20 | Female | Natural Science |

| P14 | 19 | Male | Education |

| P15 | 22 | Female | Social Work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mhlanga, N.L.; Mqushwane, A.; Ncinitwa, A.B. HIV Prevention Practices Among South African University Students. Youth 2025, 5, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040123

Mhlanga NL, Mqushwane A, Ncinitwa AB. HIV Prevention Practices Among South African University Students. Youth. 2025; 5(4):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040123

Chicago/Turabian StyleMhlanga, Nongiwe Linette, Abenathi Mqushwane, and Akhona Balindile Ncinitwa. 2025. "HIV Prevention Practices Among South African University Students" Youth 5, no. 4: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040123

APA StyleMhlanga, N. L., Mqushwane, A., & Ncinitwa, A. B. (2025). HIV Prevention Practices Among South African University Students. Youth, 5(4), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040123