Social Media in Physical Activity Interventions Targeting Obesity Among Young Adults: Trends, Challenges, and Lessons from Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Conceptual Background

3.1. Social Media in Health Promotion

3.2. Social Media and Behavior Change Theories

3.2.1. Social Cognitive Theory

3.2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior

3.2.3. Behavior Change Techniques

3.2.4. Capability, Opportunity, Motivation Behavior

3.3. Social Media and Intersectionality

4. Social Media-Driven PA Interventions

Engagement Strategies to Enhance PA Targeting Obesity

5. Social Media, PA, and Obesity Outcomes in Young Adults

5.1. Behavioral Influences

5.2. Physiological Influences

5.3. Motivational Influences

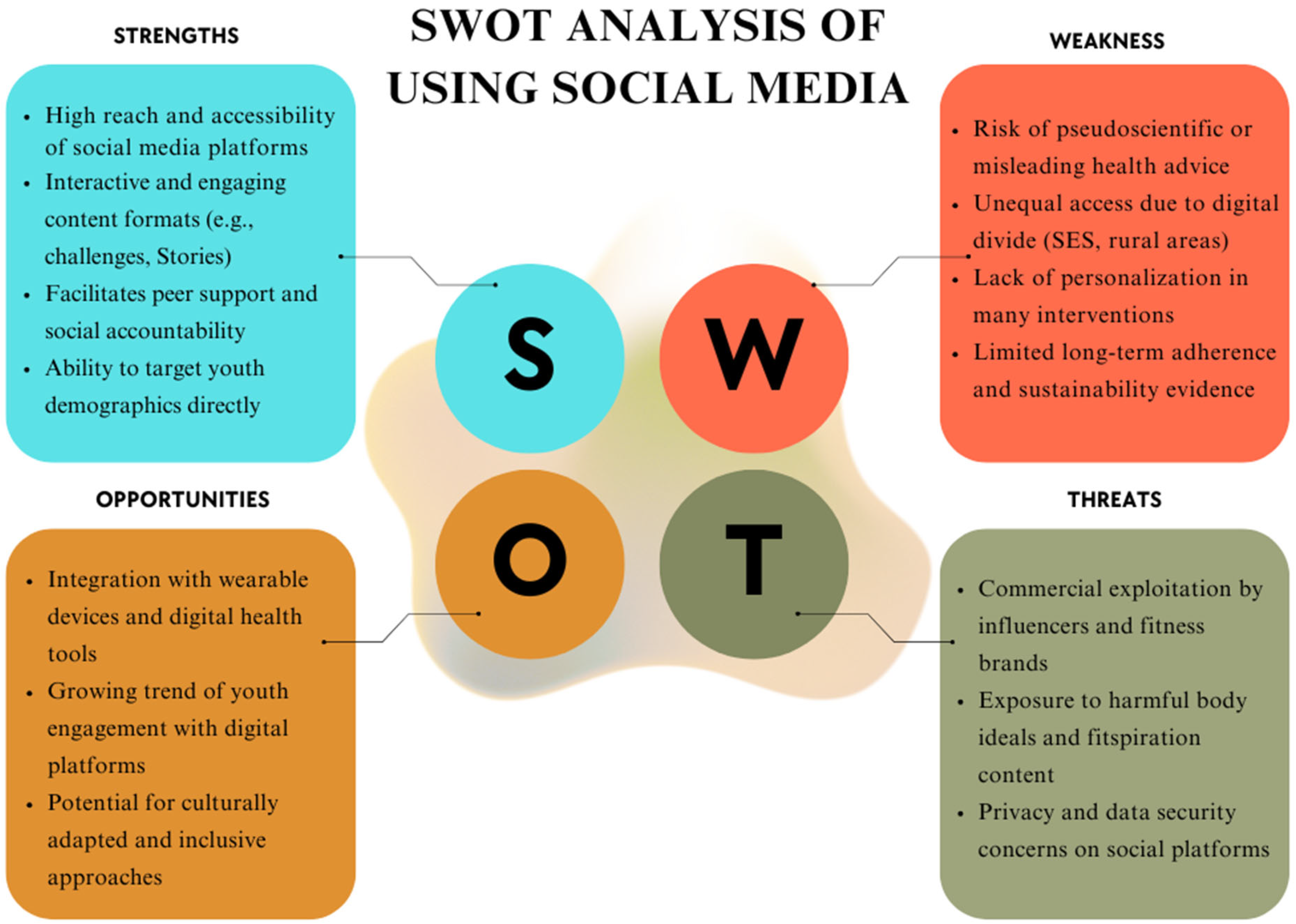

6. Challenges and Barriers

6.1. Ethical and Privacy Concerns

6.2. Digital Divide and Accessibility

6.3. Quality Control and Misinformation

7. Future Directions

7.1. Integration with Wearables & AI-Driven Multi-Platform Strategies

7.2. Co-Design with Young Adults & Personalized Adaptive Messaging

7.3. Policy Frameworks & Digital Health Standards

7.4. Recommendations for Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Physical Activity |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| USA | United States |

| USD | United States dollar |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| DBCIs | Digital behavior change interventions |

| SCT | Social Cognitive Theory |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| BCTs | Behavior Change Techniques |

| COM-B | Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behavior |

| SES | Socioeconomic Status |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats |

| JITAIs | Just-In-Time Adaptive Interventions |

| RCT | Randomized Control Trial |

References

- Abdoli, M., Scotto Rosato, M., Desousa, A., & Cotrufo, P. (2024). Cultural differences in body image: A systematic review. Social Sciences, 13, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. K., & Mohammed, R. A. (2025). Obesity: Prevalence, causes, consequences, management, preventive strategies and future research directions. Metabolism Open, 27, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mhanna, S. B., Batrakoulis, A., Wan Ghazali, W. S., Mohamed, M., Aldayel, A., Alhussain, M. H., Afolabi, H. A., Wada, Y., Gülü, M., Elkholi, S., Abubakar, B. D., & Rojas-Valverde, D. (2024). Effects of combined aerobic and resistance training on glycemic control, blood pressure, inflammation, cardiorespiratory fitness and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes and overweight/obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ, 12, e17525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althoff, T., Ivanovic, B., Delp, S., King, A., & Leskovec, J. (2024). Countrywide natural experiment reveals impact of built environment on physical activity. arXiv, arXiv:2406.04557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, A., & Tuffley, D. (2014). The gender digital divide in developing countries. Future Internet, 6(4), 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschwanden, R., & Messner, C. (2024). How influencers motivate inactive adolescents to be more physically active: A mixed methods study. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1429850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, L. M., Morgan, P. J., Hutchesson, M. J., Rollo, M. E., & Collins, C. E. (2017). Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the “HEYMAN” healthy lifestyle program for young men: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Nutrition Journal, 16(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C., Goldbeck-Wood, S., & Mertens, S. (2019). SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1998). Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology & Health, 13(4), 623–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalha, A. P. D. B., Marcal, I. R., Main, E., & Ghisi, G. L. d. M. (2025). Barriers to physical activity in women from ethnic minority groups: A systematic review. BMC Women’s Health, 25(1), 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickwood, K.-J., Watson, G., O’Brien, J., & Williams, A. D. (2019). Consumer-based wearable activity trackers increase physical activity participation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 7(4), e11819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. E. B., Richardson, K., Halil-Pizzirani, B., Atkins, L., Yücel, M., & Segrave, R. A. (2024). Key influences on university students’ physical activity: A systematic review using the Theoretical Domains Framework and the COM-B model of human behaviour. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Robles, C., Viciana, J., Guijarro-Romero, S., & Mayorga-Vega, D. (2022). Effects of consumer-wearable activity tracker-based programs on objectively measured daily physical activity and sedentary behavior among school-aged children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine Open, 8(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, D. N., Tate, D. F., Ries, A. V., Brown, J. D., DeVellis, R. F., & Ammerman, A. S. (2012). A social media-based physical activity intervention: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(5), 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cawley, J., Biener, A., Meyerhoefer, C., Ding, Y., Zvenyach, T., Smolarz, B. G., & Ramasamy, A. (2021). Direct medical costs of obesity in the United States and the most populous states. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 27(3), 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, V., & Allman-Farinelli, M. (2022). Young Australian adults prefer video posts for dissemination of nutritional information over the social media platform Instagram: A pilot cross-sectional survey. Nutrients, 14(20), 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, R. G., Prichard, I., Gosse, G., Stankevicius, A., & Maher, C. (2023). Hashtag fitspiration: Credibility screening and content analysis of Instagram fitness accounts. BMC Public Health, 23, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R. G., Ryan, J. C., Edney, S. M., & Maher, C. A. (2020). Can Instagram be used to deliver an evidence-based exercise program for young women? A process evaluation. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgostar, P., Qin, Q., Cui, S., Ashcraft, L. E., & Yousefi-Nooraie, R. (2025). Using social media to disseminate behavior change interventions: Scoping review of systematic reviews. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 27, e57370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Direito, A., Carraça, E., Rawstorn, J., Whittaker, R., & Maddison, R. (2017). mHealth technologies to influence physical activity and sedentary behaviors: Behavior change techniques, systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd-Reynolds, C., Griffin, N., Kyle, P., Scott, S., Fairbrother, H., Holding, E., Crowder, M., Woodrow, N., & Summerbell, C. (2024). Young people’s experiences of physical activity insecurity: A qualitative study highlighting intersectional disadvantage in the UK. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, T., & Li, Y. (2022). Effects of social networks in promoting young adults’ physical activity among different sociodemographic groups. Behavioral Sciences, 12(9), 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, A., Boroumandzad, N., Sherman, A. L., Christie, G., Riadi, I., & Moreno, S. (2025). Examining challenges to co-design digital health interventions with end users: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 27, e50178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durau, J., Diehl, S., & Terlutter, R. (2022). Motivate me to exercise with you: The effects of social media fitness influencers on users’ intentions to engage in physical activity and the role of user gender. Digital Health, 8, 20552076221102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E. A., Lumsden, J., Rivas, C., Steed, L., Edwards, L. A., Thiyagarajan, A., Sohanpal, R., Caton, H., Griffiths, C. J., Munafò, M. R., Taylor, S., & Walton, R. T. (2016). Gamification for health promotion: Systematic review of behaviour change techniques in smartphone apps. BMJ Open, 6(10), e012447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaheebocus, S. M. R. A., Weal, M., Morrison, L., & Yardley, L. (2018). Peer-based social media features in behavior change interventions: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(2), e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y., Ma, Y., Mo, D., Zhang, S., Xiang, M., & Zhang, Z. (2019). Methodology of an exercise intervention program using social incentives and gamification for obese children. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing, 24, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, G. T., & Mangan, R. M. (2025). Impact of social media influencers on amplifying positive public health messages. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 27, e73062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstang, K. R., Jackman, P. C., Healy, L. C., Cooper, S. B., & Magistro, D. (2024). What effect do goal setting interventions have on physical activity and psychological outcomes in insufficiently active adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 21(6), 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godino, J. G., Merchant, G., Norman, G. J., Donohue, M. C., Marshall, S. J., Fowler, J. H., Calfas, K. J., Huang, J. S., Rock, C. L., Griswold, W. G., Gupta, A., Raab, F., Fogg, B. J., Robinson, T. N., & Patrick, K. (2016). Using social and mobile tools for weight loss in overweight and obese young adults (Project SMART): A 2 year, parallel-group, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 4(9), 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Serrano, M. H., Alonso-Dos-Santos, M., Crespo-Hervás, J., & Calabuig, F. (2024). Information management in social media to promote engagement and physical activity behavior. International Journal of Information Management, 78, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, V. A., Wood, G., Skinner, B., & Thompson, J. L. (2021). The effect of social media interventions on physical activity and dietary behaviours in young people and adults: A systematic review. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18(1), 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankivsky, O., & Christoffersen, A. (2008). Intersectionality and the determinants of health: A Canadian perspective. Critical Public Health, 18(3), 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeman, W., Houghton, J., Lane, K., Jones, A., & Naughton, F. (2019). A systematic review of just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) to promote physical activity. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 16(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L. M., Blay-Tofey, M., Haeffner, C. E., Raymond, C. N., Tandilashvili, E., Terry, N., Kiderman, M., Metcalf, O., Brotman, M. A., & Lopez-Guzman, S. (2025). Just-In-Time adaptive interventions to promote behavioral health: Protocol for a systematic review. JMIR Research Protocols, 14, e58917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoebeke, R. (2008). Low-income women’s perceived barriers to physical activity: Focus group results. Applied Nursing Research: ANR, 21(2), 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchesson, M. J., Callister, R., Morgan, P. J., Pranata, I., Clarke, E. D., Skinner, G., Ashton, L. M., Whatnall, M. C., Jones, M., Oldmeadow, C., & Collins, C. E. (2018). A targeted and tailored eHealth weight loss program for young women: The be positive be eHealth randomized controlled trial. Healthcare, 6(2), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchesson, M. J., Rollo, M. E., Krukowski, R., Ells, L., Harvey, J., Morgan, P. J., Callister, R., Plotnikoff, R., & Collins, C. E. (2015). eHealth interventions for the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 16(5), 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydari, M. Z., Adjerid, I., & Striegel, A. D. (2023). Health wearables, gamification, and healthful activity. Management Science, 69(7), 3920–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakicic, J. M., Rogers, R. J., Davis, K. K., & Collins, K. A. (2018). Role of physical activity and exercise in treating patients with overweight and obesity. Clinical Chemistry, 64(1), 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerónimo, F., & Carraça, E. V. (2022). Effects of fitspiration content on body image: A systematic review. Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 27(8), 3017–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanchan, S., & Gaidhane, A. (2023). Social media role and its impact on public health: A narrative review. Cureus, 15(1), e33737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kbaier, D., Kane, A., McJury, M., & Kenny, I. (2024). Prevalence of health misinformation on social media—Challenges and mitigation before, during, and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic: Scoping literature review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 26, e38786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilfoy, A., Hsu, T.-C. C., Stockton-Powdrell, C., Whelan, P., Chu, C. H., & Jibb, L. (2024). An umbrella review on how digital health intervention co-design is conducted and described. NPJ Digital Medicine, 7(1), 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Youm, H., Kim, S., Choi, H., Kim, D., Shin, S., & Chung, J. (2024). Exploring the influence of YouTube on digital health literacy and health exercise intentions: The role of parasocial relationships. Behavioral Sciences, 14(4), 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvari, M., Karipidou, M., Tsiampalis, T., Mamalaki, E., Poulimeneas, D., Bathrellou, E., Panagiotakos, D., & Yannakoulia, M. (2022). Digital health interventions for weight management in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(2), e30675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M. W., & McClure, S. M. (2004). The role of culture in health communication. Annual Review of Public Health, 25, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzman, G. W., Day, S. C., Small, D. S., Lynch, M., Zhu, J., Wang, W., Rareshide, C. A. L., & Patel, M. S. (2018). Social incentives and gamification to promote weight loss: The LOSE IT randomized, controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(10), 1669–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, L., Quiroz, J. C., Tong, H. L., Arevalo Bazalar, M., & Coiera, E. (2020). A mobile social networking app for weight management and physical activity promotion: Results from an experimental mixed methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(12), e19991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P. W. C., Wang, J. J., Ransdell, L. L., & Shi, L. (2022). The effectiveness of Facebook as a social network intervention to increase physical activity in Chinese young adults. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 912327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, H. A., McVay, M. A., Pearl, R. L., Fisher, C. L., & Jake-Schoffman, D. E. (2025). The impact of fitness influencers on physical activity outcomes: A scoping review. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-A., & Park, J.-H. (2025). Systematic review and meta analysis of standalone digital behavior change interventions on physical activity. NPJ Digital Medicine, 8(1), 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, B. A., Williams, D. M., Frayeh, A., & Marcus, B. H. (2016). Self-efficacy versus perceived enjoyment as predictors of physical activity behaviour. Psychology & Health, 31(4), 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Z. H., & Danayan, S. (2021). The protocol and feasibility results of a preliminary Instagram-based physical activity promotion study. Technologies, 9(4), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M., Pan, Y., Zhong, T., Zeng, Y., & Cheng, A. S. K. (2021). Effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise on metabolic syndrome parameters and cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine, 22(4), 1523–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H., Jung, E., Jodoin, K., Du, X., Airton, L., & Lee, E.-Y. (2021). Operationalization of intersectionality in physical activity and sport research: A systematic scoping review. SSM Population Health, 14, 100808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H., Chen, H., Liu, Q., Xu, J., & Li, S. (2024). A meta-analysis of the relationship between social support and physical activity in adolescents: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1305425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Zhang, Z., Wang, B., Meng, T., Li, C., & Zhang, X. (2024). Global health impacts of high BMI: A 30-year analysis of trends and disparities across regions and demographics. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 217, 111883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., & Willoughby, J. F. (2018). Do fitness apps need text reminders? An experiment testing goal-setting text message reminders to promote self-monitoring. Journal of Health Communication, 23(4), 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Y. L., Yaw, Q. P., & Lau, Y. (2023). Social media-based interventions for adults with obesity and overweight: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. International Journal of Obesity, 47(7), 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looyestyn, J., Kernot, J., Boshoff, K., & Maher, C. (2018). A web-based, social networking beginners’ running intervention for adults aged 18 to 50 years delivered via a Facebook group: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(2), e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano-Chacon, B., Suarez-Lledo, V., & Alvarez-Galvez, J. (2021). Use and effectiveness of social-media-delivered weight loss interventions among teenagers and young adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, C. A., Ferguson, M., Vandelanotte, C., Plotnikoff, R., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Thomas, S., Nelson-Field, K., & Olds, T. (2015). A web-based, social networking physical activity intervention for insufficiently active adults delivered via Facebook app: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(7), e174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, C. A., Lewis, L. K., Ferrar, K., Marshall, S., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., & Vandelanotte, C. (2014). Are health behavior change interventions that use online social networks effective? A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(2), e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, J., Partridge, S. R., Kemper, J. A., Braakhuis, A., & Roy, R. (2023). Co-design of digital health interventions with young people: A scoping review. Digital Health, 9, 20552076231219116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamede, A., Erdem, Ö., Noordzij, G., Merkelbach, I., Kocken, P., & Denktaş, S. (2022). Exploring the intersectionality of family SES and gender with psychosocial, behavioural and environmental correlates of physical activity in Dutch adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vizcaíno, V., Fernández-Rodríguez, R., Reina-Gutiérrez, S., Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, E., Garrido-Miguel, M., Núñez de Arenas-Arroyo, S., & Torres-Costoso, A. (2024). Physical activity is associated with lower mortality in adults with obesity: A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCashin, D., & Murphy, C. M. (2023). Using TikTok for public and youth mental health—A systematic review and content analysis. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28(1), 279–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, J., Dobson, R., Whittaker, R., & Paton, C. (2022). Mobile health (mHealth) in low- and middle-income countries. Annual Review of Public Health, 43, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, D. J., Helgeson, M. A., Liu, W., & Gao, Z. (2022). Effects of a remote, YouTube-delivered exercise intervention on young adults’ physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 11(2), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., Eccles, M. P., Cane, J., & Wood, C. E. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, M. A., Goniu, N., Moreno, P. S., & Diekema, D. (2013). Ethics of social media research: Common concerns and practical considerations. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16(9), 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motevalli, M. (2025). Comparative analysis of systematic, scoping, umbrella, and narrative reviews in clinical research: Critical considerations and future directions. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 99, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, M. A., Hayes, S., Bennett, G. G., Ives, A. K., & Foster, G. D. (2013). Using Facebook and text messaging to deliver a weight loss program to college students. Obesity, 21(1), 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, M. A., Whiteley, J. A., Mavredes, M., Tjaden, A. H., Simmens, S., Hayman, L. L., Faro, J., Winston, G., Malin, S., & DiPietro, L. (2021). Effect of tailoring on weight loss among young adults receiving digital interventions: An 18 month randomized controlled trial. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11(4), 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, K., Teah, G., Cooke, R., Li, X., Brown, K., Salisbury-Finch, B., Kwah, K., Bartle, N., Curtis, K., Fulton, E., Parsons, J., Dusseldorp, E., & Williams, S. L. (2021). Do automated digital health behaviour change interventions have a positive effect on self-efficacy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 15(1), 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M., Dai, X., Cogen, R. M., Abdelmasseh, M., Abdollahi, A., Abdullahi, A., Aboagye, R. G., Abukhadijah, H. J., Adeyeoluwa, T. E., Afolabi, A. A., Ahmad, D., Ahmad, N., Ahmed, A., Ahmed, S. A., Akkaif, M. A., Akrami, A. E., Al Hasan, S. M., Al Ta, O., Alahdab, F., … Gakidou, E. (2024). National-level and state-level prevalence of overweight and obesity among children, adolescents, and adults in the USA, 1990–2021, and forecasts up to 2050. Lancet, 404(10469), 2278–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, S. K., Kavanagh, M. E., Ramboanga, K., Ayoub-Charette, S., Modol, S., Dias, G. M., Kendall, C. W. C., Sievenpiper, J. L., & Chiavaroli, L. (2024). Effect of digital health applications with or without gamification on physical activity and cardiometabolic risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. EClinicalMedicine, 76, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, C. D., & Skinner, H. A. (2006). eHealth literacy: Essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 8(2), e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, S., Khoong, E. C., Lyles, C. R., & Karliner, L. (2020). Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Catalyst Non-Issue Content, 1(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhn, W. N., Wick, M. R., Brown, M. P., Green, T. J., & Harriger, J. A. (2025). Understanding fitness trends in the virtual age: A content analysis of TikTok workout videos. Health Communication, 40(8), 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, N., Jerin, S. I., & Mu, D. (2023). Using TikTok to educate, influence, or inspire? A content analysis of health-related EduTok videos. Journal of Health Communication, 28(8), 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagoto, S., Schneider, K., Jojic, M., DeBiasse, M., & Mann, D. (2013). Evidence-based strategies in weight-loss mobile apps. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(5), 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M. S., Small, D. S., Harrison, J. D., Fortunato, M. P., Oon, A. L., Rareshide, C. A. L., Reh, G., Szwartz, G., Guszcza, J., Steier, D., Kalra, P., & Hilbert, V. (2019). Effectiveness of behaviorally designed gamification interventions with social incentives for increasing physical activity among overweight and obese adults across the United States: The STEP UP randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 179(12), 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, N., Braithwaite, R. E., Biddle, S. J. H., van Sluijs, E. M. F., & Atkin, A. J. (2014). Associations between sedentary behaviour and physical activity in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 15(8), 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picazo-Sánchez, L., Domínguez-Martín, R., & García-Marín, D. (2022). Health promotion on Instagram: Descriptive-correlational study and predictive factors of influencers’ content. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 15817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryde, S., & Prichard, I. (2022). TikTok on the clock but the #fitspo don’t stop: The impact of TikTok fitspiration videos on women’s body image concerns. Body Image, 43, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, M., Allen, H., Huang, S., Vazquez, M., Warner, E., & Thompson, D. (2024). Mediterranean diet information on TikTok and implications for digital health promotion research: Social media content analysis. JMIR Formative Research, 8, e51094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rote, A. E., Klos, L. A., Brondino, M. J., Harley, A. E., & Swartz, A. M. (2015). The efficacy of a walking intervention using social media to increase physical activity: A randomized trial. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 12(Suppl. S1), S18–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S. A., & Masters, R. M. (2021). Disparities in health care and the digital divide. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(9), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattora, E. A., Ganeles, B. C., Pierce, M. E., & Wong, R. (2024). Research on health topics communicated through TikTok: A systematic review of the literature. Journalism and Media, 5(3), 1395–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawesi, S., Rashrash, M., Phalakornkule, K., Carpenter, J. S., & Jones, J. F. (2016). The impact of information technology on patient engagement and health behavior change: A systematic review of the literature. JMIR Medical Informatics, 4(1), e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, A. T., Rajkumar, E., Tejaswini, P., Lakshmi, R., & Romate, J. (2021). Applying social cognitive theory to predict physical activity and dietary behavior among patients with type-2 diabetes. Health Psychology Research, 9(1), 24510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiler, J., Libby, T. E., Jackson, E., Lingappa, J. R., & Evans, W. D. (2022). Social media-based interventions for health behavior change in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(4), e31889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabu, S. A., Saka, M. H., Al-Banna, D. A., Zaki, S. M., Ahmed, H. M., & Shabila, N. P. (2023). A cross-sectional study on the perceived barriers to physical exercise among women in Iraqi Kurdistan Region. BMC Women’s Health, 23(1), 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shameli, A., Althoff, T., Saberi, A., & Leskovec, J. (2017, April 3–7). How gamification affects physical activity: Large-scale analysis of walking challenges in a mobile application [Conference session]. International World-Wide Web Conference (pp. 455–463), Perth, Australia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyab, W., Halcomb, E., Rolls, K., & Ferguson, C. (2023). The Impact of social media interventions on weight reduction and physical activity improvement among healthy adults: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e38429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, E. A., Mendonça, C. R., Delpino, F. M., Elias Souza, G. V., Pereira de Souza Rosa, L., de Oliveira, C., & Noll, M. (2022). Sedentary behavior, physical inactivity, abdominal obesity and obesity in adults and older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, 50, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeon, R., Dewidar, O., Trawin, J., Duench, S., Manson, H., Pardo Pardo, J., Petkovic, J., Hatcher Roberts, J., Tugwell, P., Yoganathan, M., Presseau, J., & Welch, V. (2020). Behavior Change techniques included in reports of social media interventions for promoting health behaviors in adults: Content analysis within a systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e16002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K., & Perez, C. (2021). You follow fitness influencers on YouTube. But do you actually exercise? How parasocial relationships, and watching fitness influencers, relate to intentions to exercise. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Lledo, V., & Alvarez-Galvez, J. (2021). Prevalence of health misinformation on social media: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(1), e17187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X., Teljeur, I., Li, Z., & Bosch, J. A. (2024, July 8–10). Can a funny chatbot make a difference? Infusing humor into conversational agent for behavioral intervention [Conference session]. ACM Conference on Conversational User Interfaces, Luxembourg. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvia Chou, W.-Y., Gaysynsky, A., & Cappella, J. N. (2020). Where we go from here: Health misinformation on social media. American Journal of Public Health, 110(Suppl. S3), S273–S275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielen, S. C., Reusch, J. E. B., & Regensteiner, J. G. (2023). A narrative review of exercise participation among adults with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes: Barriers and solutions. Frontiers in Clinical Diabetes and Healthcare, 4, 1218692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D., Cantu, D., Ramirez, B., Cullen, K. W., Baranowski, T., Mendoza, J., Anderson, B., Jago, R., Rodgers, W., & Liu, Y. (2016). Texting to increase adolescent physical activity: Feasibility assessment. American Journal of Health Behavior, 40(4), 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M., & Zaccardo, M. (2018). “Strong is the new skinny”: A content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(8), 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricás-Vidal, H. J., Vidal-Peracho, M. C., Lucha-López, M. O., Hidalgo-García, C., Monti-Ballano, S., Márquez-Gonzalvo, S., & Tricás-Moreno, J. M. (2022). Impact of fitness influencers on the level of physical activity performed by Instagram users in the United States of America: Analytical cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, C. G., Tate, D. F., Mayer, D. K., Allicock, M., & Cai, J. (2013). A randomized trial of a Facebook-based physical activity intervention for young adult cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: Research and Practice, 7(3), 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woudenberg, T. J., Bevelander, K. E., Burk, W. J., Smit, C. R., Buijs, L., & Buijzen, M. (2018). A randomized controlled trial testing a social network intervention to promote physical activity among adolescents. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Cheng, R., Xie, L., & Hu, F. (2023). Comparative efficacy of exercise training modes on systemic metabolic health in adults with overweight and obesity: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14, 1294362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., McKee, M., Torbica, A., & Stuckler, D. (2019). Systematic literature review on the spread of health-related misinformation on social media. Social Science & Medicine, 240, 112552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westbury, S., Oyebode, O., van Rens, T., & Barber, T. M. (2023). Obesity stigma: Causes, consequences, and potential solutions. Current Obesity Reports, 12(1), 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G., Hamm, M. P., Shulhan, J., Vandermeer, B., & Hartling, L. (2014). Social media interventions for diet and exercise behaviours: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open, 4(2), e003926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M. L., Burnap, P., & Sloan, L. (2017). Crime sensing with big data: The affordances and limitations of using open-source communications to estimate crime patterns. The British Journal of Criminology, 57(2), 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, T. J., Pang, B., & Rundle-Thiele, S. (2021). Capability, opportunity, and motivation: An across contexts empirical examination of the COM-B model. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., Li, G., Du, L., Chen, S., Zhang, X., & He, Q. (2023). The effectiveness of wearable activity trackers for increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary time in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Digital Health, 9, 205520762311767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X., Huang, D., & Li, G. (2025). The impact of fitness social media use on exercise behavior: The chained mediating role of intrinsic motivation and exercise intention. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1635912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, G., Fortuna, K. L., Lansford, J. E., & Rudolph, K. D. (2025). The effects of digital peer support interventions on physical and mental health: A review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 34, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, Y. Y., Makmor-Bakry, M., & Chong, W. W. (2024). Elements Influencing user engagement in social media posts on lifestyle risk factors: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 26, e59742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Brackbill, D., Yang, S., & Centola, D. (2015). Efficacy and causal mechanism of an online social media intervention to increase physical activity: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine Reports, 2, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M. (2010). “But the data is already public”: On the ethics of research in Facebook. Ethics and Information Technology, 12(4), 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theory | Core Components | Applications in Social Media | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) | Observational learning, self-efficacy, outcome expectations | Users observe influencers/peers modeling healthy behaviors on platforms like Instagram or TikTok; increases confidence and motivation to engage in physical activity. | (Bandura, 1998) (Bandura, 2001) (Durau et al., 2022) |

| Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) | Attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control | Peer challenges and supportive comments improve subjective norms and perceived control; intentions are strengthened. | (Ajzen, 1991) (Xiao et al., 2025) |

| Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs) | Goal setting, self-monitoring, feedback on performance | Apps and social media platforms integrate BCTs (e.g., fitness tracking, reminders, likes) to maintain engagement and behavior. | (Goodyear et al., 2021) (Direito et al., 2017) (Michie et al., 2013) (Sebastian et al., 2021) |

| COM-B | Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behavior | Social media enhances capability (tutorials), opportunity (communities), and motivation (gamification, social support). | (Michie et al., 2011) (Brown et al., 2024) (Willmott et al., 2021) |

| Platform | Core Functionalities | Approach Used in Interventions | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual storytelling, identity presentation | Fitness challenges, transformation posts, motivational imagery, peer-led stories | (Curtis et al., 2020) (Z. H. Lewis & Danayan, 2021) (Tricás-Vidal et al., 2022) (Picazo-Sánchez et al., 2022) | |

| YouTube | Long-form videos, tutorials, parasocial engagement | Vlogs, structured home workouts, influencer-led programs | (Kim et al., 2024) (Sokolova & Perez, 2021) (McDonough et al., 2022) |

| TikTok | Short-form, trend-driven videos | Fitspiration, dance/exercise trends, motivational framing | (Nuhn et al., 2025) (Pryde & Prichard, 2022) (McCashin & Murphy, 2023) |

| Group-based features, peer interaction, long-form content | Private fitness groups, goal tracking, messaging threads | (Lau et al., 2022) (Looyestyn et al., 2018) (Valle et al., 2013) (Maher et al., 2015) |

| Study | Country | Population | Platform | Intervention | Measures | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ashton et al., 2017) | Australia | n = 50; young men aged 18–25 y | 3-month program: eHealth (website, wearable, Facebook group) along with face-to-face sessions, and home-based exercise | Steps/day, diet quality, MVPA, anthropometrics, cholesterol | Improvements in MVPA; reduction in weight, BMI, fat, waistline, cholesterol; no steps/day change | |

| (Cavallo et al., 2012) | USA | n = 134; university students | Website + Facebook group | 12-week program using fitness education, self-monitoring, peer support vs. web-only | Social support for PA, self-reported PA | Increased social support in intervention group; PA improvement |

| (Curtis et al., 2020) | Australia | n = 16; 100% females; mean age = 23 y | 12-week quasi-experimental program; daily running and weight exercise, and video demonstrations | self-reported PA, cardiorespiratory fitness | slight fitness improvement | |

| (Godino et al., 2016) | USA | n = 404; overweight young adults; mean age = 22.7 y | Facebook, apps, SMS, email, website | 2-year adaptive theory-based weight-loss program with multi-channel delivery & coach support | Weight at 6, 12, 18, 24 months | Weight improvements at 6 and 12 months; no sig differences at 18 or 24 months |

| (Hutchesson et al., 2018) | Australia | n = 57; young women; age = 18–35 y | Facebook, website, app, email, SMS | 6-month tailored e-health program with self-monitoring & lifestyle guidance via multi-channels | Weight, body fat, diet | Reduction in body; no sig weight loss vs. control |

| (McDonough et al., 2022) | USA | n = 64; 75% females; mean age = 22.8 y | YouTube | 12-week RCT including remote aerobic and strength training program based on self-determination theory with instructional videos | MVPA, strength frequency, intrinsic motivation, perceived PA barriers | Improvements in MVPA and strength frequency |

| (Napolitano et al., 2013) | USA | n = 52; college students; 86% females; mean age = 20.5 y | 8-week weight loss program, with or without additional text messaging and personalized feedback | Weight change | Weight reduction in Facebook + peer support group | |

| (Napolitano et al., 2021) | USA | n = 459; overweight young adults; mean age = 23.3 y | Facebook, SMS | 18-month digital weight-loss program: tailored vs. generic vs. control | Weight at 6, 12, 18 months | Short-term weight loss at 6 m in highly engaged tailored group, but not sustained |

| (Patel et al., 2019) | USA | n = 602; overweight young adults | Mobile app with social features | 12-week gamified PA program with team challenges & rewards | Self-reported PA, weight | Improvements in PA; significant weight reduction vs. control |

| (Rote et al., 2015) | USA | n = 63; female students; mean age = 18.1 y | 8-week walking + peer support program vs. self-monitoring only | Steps/day | Step counts improvements in Facebook group compared to control |

| Challenge | Summary | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical & privacy concerns | Insufficient transparency in data sharing, unclear in-formed consent, continuous monitoring, and spread of pseudoscientific advice threaten user privacy and data security. | (M. L. Williams et al., 2017) (Moreno et al., 2013) (Zimmer, 2010) (Y. Wang et al., 2019) (Sylvia Chou et al., 2020) |

| Digital divide & accessibility | Economic, geographic, gender, language, and cultural disparities limit access to social media interventions and reduce digital health literacy. | (Saeed & Masters, 2021) (McCool et al., 2022) (Antonio & Tuffley, 2014) (Nouri et al., 2020) |

| Quality control & misinformation | Lack of quality control leads to widespread misinformation, promotion of unrealistic body ideals, and heterogeneous intervention outcomes, especially harming low health literacy users. | (Suarez-Lledo & Alvarez-Galvez, 2021) (Curtis et al., 2023) (Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2018) (Pryde & Prichard, 2022) (Raber et al., 2024) (Kbaier et al., 2024) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hematabadi, A.; Rashidlamir, A.; Radfar, B.; Shourabi, P.; Hajimousaei, S.; Schauer, M.; Motevalli, M. Social Media in Physical Activity Interventions Targeting Obesity Among Young Adults: Trends, Challenges, and Lessons from Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook. Youth 2025, 5, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040111

Hematabadi A, Rashidlamir A, Radfar B, Shourabi P, Hajimousaei S, Schauer M, Motevalli M. Social Media in Physical Activity Interventions Targeting Obesity Among Young Adults: Trends, Challenges, and Lessons from Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook. Youth. 2025; 5(4):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040111

Chicago/Turabian StyleHematabadi, Ahmad, Amir Rashidlamir, Bahareh Radfar, Pouria Shourabi, Soheil Hajimousaei, Markus Schauer, and Mohamad Motevalli. 2025. "Social Media in Physical Activity Interventions Targeting Obesity Among Young Adults: Trends, Challenges, and Lessons from Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook" Youth 5, no. 4: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040111

APA StyleHematabadi, A., Rashidlamir, A., Radfar, B., Shourabi, P., Hajimousaei, S., Schauer, M., & Motevalli, M. (2025). Social Media in Physical Activity Interventions Targeting Obesity Among Young Adults: Trends, Challenges, and Lessons from Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook. Youth, 5(4), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5040111