The Pitfalls and Promises of Sports Participation and Prescription Drug Misuse Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrumentation

2.1.1. Independent Variables

2.1.2. Dependent Variable

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

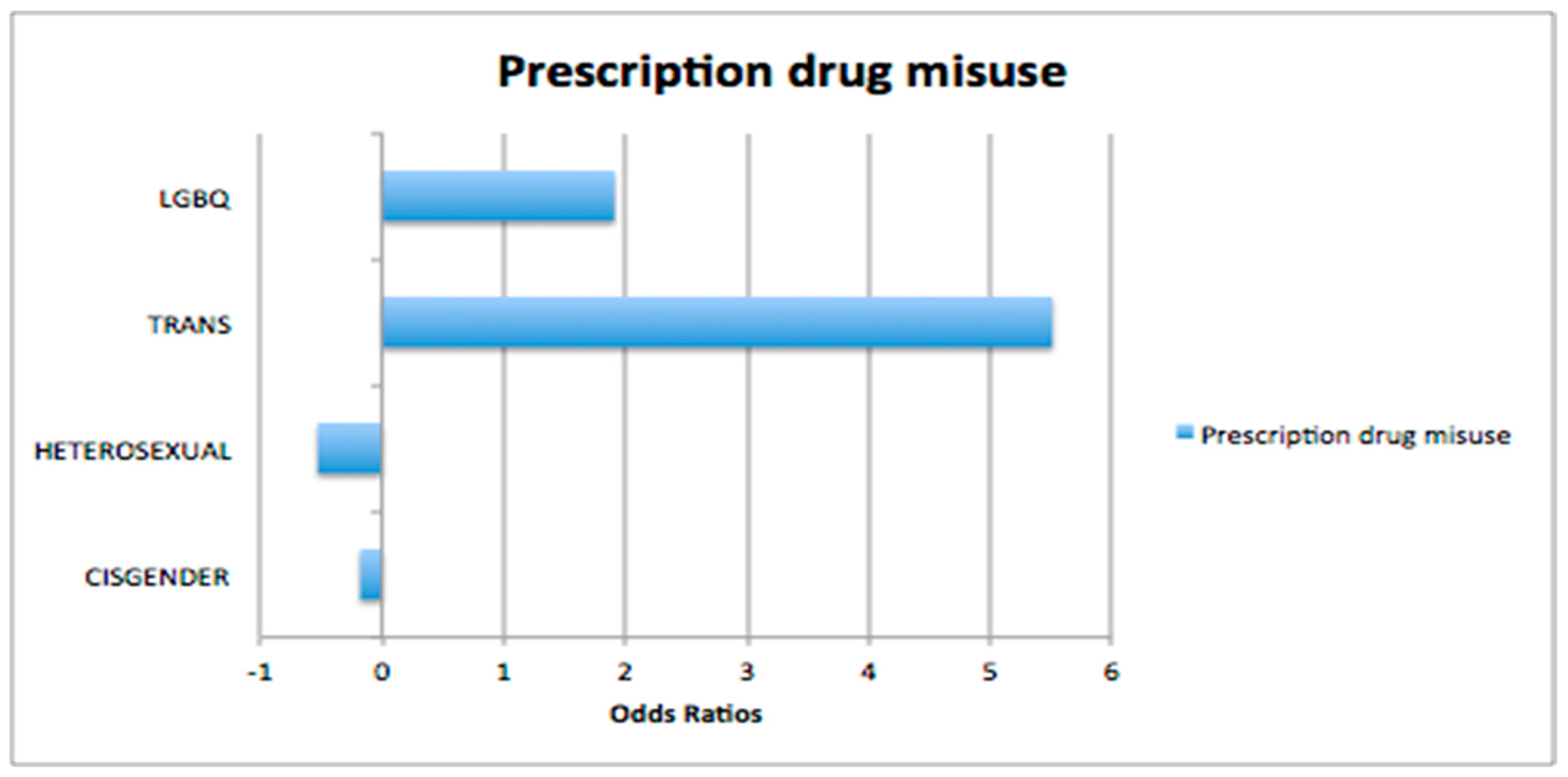

3.2. Identity

3.3. Sports Team Participation

3.3.1. Sexual Orientation and Sports Team Participation

3.3.2. Gender Identity and Sports Team Participation

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Research

4.2. Implications for School Health Policy, Practice, and Equity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control |

| YRBS | Youth Risk Behavior Survey |

| 1 | Explanation of terminology choice—authors use a variety of terms when conducting research on or with youth who are not heterosexual and/or cisgender. Some use acronyms, while others use the phrase “sexual and/or gender minority youth.” |

References

- Anderson, E., Alder, J., Turner, G., Batten, J., & Hardwicke, J. (2025). The experiences of transgender student-athletes. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspen Institute. (n.d.). Children’s bill of rights in sports. Available online: https://projectplay.org/childrens-rights-and-sports (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C. M., & Kosciw, J. G. (2022). Engaged or excluded: LGBTQ youth’s participation in school sports and their relationship to psychological well-being. Psychology in the Schools, 59(1), 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, J. (2011). Youth sports: What counts as “positive development?”. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 35(3), 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, T. H., Ross-Reed, D. E., FitzGerald, C. A., Overton, K., Landrau-Cribbs, E., & Schiff, M. (2023). Effects of school policies and programs on violence among all high school students and sexual and gender minority students. Journal of School Health, 93(8), 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J. K., Fish, J. N., Perez-Brumer, A., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Russell, S. T. (2017). Transgender youth substance use disparities: Results from a population-based sample. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(6), 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChants, J. P., Green, A. E., Price, M. N., & Davis, C. K. (2024). “I get treated poorly in regular school—Why add to it?”: Transgender girls’ experiences choosing to play or not play sports. Transgender Health, 9(1), 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, B. E. (2014). High school sports participation and substance use: Differences by sport, race, and gender. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 23(3), 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, E., Jeanes, R., Faulkner, N., & O’Brien, K. S. (2021). The relationship between ‘coming out’ as lesbian, gay, or bisexual and experiences of homophobic behaviour in youth team sports. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 18(3), 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pedro, K. T., & Gorse, M. M. (2023). Substance use among transgender youth: Associations with school-based victimization and school protective factors. Journal of LGBT Youth, 20(2), 390–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, K., Thiel, A., Zipfel, S., Mayer, J., & Litaker, D. G. (2012). How healthy is the behavior of young athletes? A systematic literature review and meta-analyses. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 11(2), 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, M. S. (2014). Association between physical activity and substance use behaviors among high school students participating in the 2009 youth risk behavior survey. Psychological Reports, 114(3), 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitle, D., Turner, R. J., & Eitle, T. M. (2003). The deterrence hypothesis reexamined: Sports participation and substance use among young adults. Journal of Drug Issues, 33(1), 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, K. M. L., Kovacek, K., Abramovich, A., & Dermody, S. S. (2023). Substance use prevalence, patterns, and correlates in transgender and gender diverse youth: A scoping review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 250, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GLSEN, ASCA, ACSSW & SSWAA. (2019). Supporting safe and healthy schools for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer students: A national survey of school counselors, social workers, and psychologists. Available online: https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/Supporting_Safe_and_Healthy_Schools_%20Mental_Health_Professionals_2019.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Goldbach, J. T., Tanner-Smith, E. E., Bagwell, M., & Dunlap, S. (2014). Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prevention Science, 15(3), 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, S. B., Griffith, C., Hayes, C. R., & Murtagh, E. F. (2019). LGBTQ+ and ally youths’ school athletics perspectives: A mixed-method analysis. Journal of LGBT Youth, 16(4), 403–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, B. T. (2023). Highlighting trans joy: A call to practitioners, researchers, and educators. Health Promotion Practice, 24(4), 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, L. (2020). Are sexual minorities more at risk? Bullying victimization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(21–22), 4960–4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaja, S. M., Gower, A. L., Parchem, B., Adler, S. J., Mcguire, J. K., Rider, G. N., & Eisenberg, M. E. (2025). Sports team participation, bias-based bullying, and mental health among transgender and gender diverse adolescents. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, J. D., Jackman, K. B., Wolff, M., Veldhuis, C. B., & Hughes, T. L. (2018). Risk and protective factors for substance use among sexual and gender minority youth: A scoping review. Current Addiction Report, 5(2), 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulick, A., Wernick, L. J., Espinoza, M. A. V., Newman, T. J., & Dessel, A. B. (2019). Three strikes and you’re out: Culture, facilities, and participation among LGBTQ youth in sports. Sport, Education and Society, 24(9), 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M., Bobko, S., Faulkner, G., Donnelly, P., & Cairney, J. (2014). Sport participation and alcohol and illicit drug use in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Addictive Behaviors, 39(3), 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereish, E. H. (2019). Substance use and misuse among sexual and gender minority youth. Current Opinion in Psychology, 30, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychology Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, R., Matthews, D. D., DeChants, J. P., Hobaica, S., Clark, C. M., Taylor, A. B., & Muñoz, G. (2024). 2024 U.S. national survey on the mental health of LGBTQ+ young people. The Trevor Project. Available online: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2024 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- National Association of School Psychologist. (2014). Safe schools for transgender and gender diverse students. Available online: https://www.nasponline.org/assets/Documents/Research%20and%20Policy/Position%20Statements/Transgender_PositionStatement.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Neary, A., & McBride, R. S. (2024). Beyond inclusion: Trans and gender diverse young people’s experiences of PE and school sport. Sport, Education and Society, 29(5), 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, M., & Mattheus, D. (2022). Addressing health disparities in LGBTQ youth through professional development of middle school staff. Journal of School Health, 92, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B. A., & Schmitz, R. M. (2021). Beyond resilience: Resistance in the lives of LGBTQ youth. Sociology Compass, 15(12), e12947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S. T. (2005). Beyond risk: Resilience in the lives of sexual minority youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education, 2(3), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstone, P. H., Bercov, M., Suen, V. Y. M., Allen, A., Cribben, I., Goodrick, J., Henry, S., Pryce, C., Langstraat, P., Rittenbach, K., Chakraborty, S., Engles, R. C., & McCabe, C. (2017). Long-term results from the Empowering a Multimodal Pathway Toward Healthy Youth Program, a multimodal school-based approach, show marked reductions in suicidality, depression, and anxiety in 6227 students in grades 6–12 (aged 11–18). Frontiers Psychiatry, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. A., & Dickey, L. M. (2017). Affirmative counseling and psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming clients. In K. A. DeBord, A. R. Fischer, K. J. Bieschke, & R. M. Perez (Eds.), Handbook of sexual orientation and gender diversity in counseling and psychotherapy (pp. 157–182). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, W. (2025, February 11). Judge orders restoration of federal health websites. NPR. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/shots-health-news/2025/02/11/nx-s1-5293387/judge-orders-cdc-fda-hhs-websites-restored (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Swadener, E. B. (1990). Children and families “at risk”: Etiology, critique, and alternative paradigms. The Journal of Educational Foundations, 4(4), 17. [Google Scholar]

- The Trevor Project. (2020). LGBTQ youth sports participation: June 2020. Available online: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/June-2020-Brief-LGBTQ-Youth-Sports-Participation-Research-Brief.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- The Trevor Project. (2021). LGBTQ youth sports participation: September 2021. Available online: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/LGBTQ-Youth-and-Sports_-September-Research-Brief-2.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Underwood, J. M., Brener, N., Thornton, J., Harris, W. A., Bryan, L. N., Shanklin, S. L., Deputy, N., Roberts, A. M., Queen, B., Chyen, D., Whittle, L., Lim, C., Yamakawa, Y., Leon-Nguyen, M., Kilmer, G., Smith-Grant, J., Demissie, Z., Jones, S. E., Clayton, H., & Dittus, P. (2020). Overview and methods for the youth risk behavior surveillance system—United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz, P., Boyd, C., & McCabe, S. E. (2013). Playing through pain: Sports participation and nonmedical use of opioid medications among adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), e28–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz, P., Epstein-Ngo, Q. M., Meier, E., Ross-Durow, P. L., McCabe, S. E., & Boyd, C. J. (2014). Painfully obvious: A longitudinal examination of medical use and misuse of opioid medication among adolescent sports participants. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(3), 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz, P., Schulenberg, J., Patrick, M., Kloska, D., McCabe, S. E., & Zarrett, N. (2017). Competitive sports participation in high school and subsequent substance use in young adulthood: Assessing differences based on level of contact. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(2), 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz, P., Schulenberg, J. E., Zdroik, J., Werner, K. S., & McCabe, S. E. (2022). The initiation and developmental course of prescription drug misuse among high school athletes during the transition through young adulthood. American Journal of Epidemiology, 191(11), 1886–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, R. V., Kuhns, L. M., Phillips, G., Wang, X., Wolf, S. F., Garofalo, R., Reisner, S., & Beach, L. B. (2023). Physical inactivity and the role of bullying among gender minority youth participating in the 2017 and 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of Adolescent Health, 72(2), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R. J., Fish, J. N., Denary, W., Caba, A., Cunningham, C., & Easton, L. (2021). LGBTQ state policies: A lever for reducing SGM youth substance use and bullying. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. R., McKenna, J. L., Artessa, L., & Moore, L. B. M. (2023). Team effort: A call for mental health clinicians to support sports access for transgender and gender diverse youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 62(8), 837–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. C., Burns, K. E., Battista, K., De Groh, M., Jiang, Y., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2020). High school sport participation and substance use: A cross-sectional analysis of students from the COMPASS study. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 12, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Range | Frequency | μ | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Sports Team Participation | 0–1 | 2694 | 44.5% | 0.497 |

| LGBQ | 0–1 | 1119 | 18.5% | 0.388 |

| Trans | 0–1 | 87 | 1.4% | 0.119 |

| LGBQ*Sports Team Participation | 0–1 | 383 | 6.3% | 0.245 |

| Trans*Sports Team Participation | 0–1 | 43 | 0.7% | 0.084 |

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Prescription Drug Misuse | 0–1 | 863 | 14% | 0.350 |

| Controls | ||||

| Sex (female) | 0–1 | 3296 | 54.5% | 0.498 |

| Am Ind/Alas Native/Haw other PI | 0–1 | 66 | 1.1% | 0.104 |

| Asian | 0–1 | 152 | 2.5% | 0.157 |

| Black or African American | 0–1 | 1196 | 19.8% | 0.398 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0–1 | 2540 | 42% | 0.493 |

| Multiple races (non-Hispanic) | 0–1 | 268 | 4.4% | 0.205 |

| White | 0–1 | 1828 | 30.2% | 0.459 |

| (LGBQ Students) | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

| β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | |

| Sports team participation | -- | -- | -- | 0.259 | 1.296 *** | 0.075 | -- | -- | -- | 0.192 | 1.211 * | 0.087 |

| LGBQ*Sports | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.457 | 1.579 ** | 0.148 | 0.265 | 1.303 | 0.172 |

| LGBQ | 0.644 | 1.905 *** | 0.086 | 0.673 | 1.960 *** | 0.086 | 0.474 | 1.607 *** | 0.104 | 0.563 | 1.757 *** | 0.113 |

| Sex (female) | 0.267 | 1.306 *** | 0.077 | 0.286 | 1.332 *** | 0.077 | 0.265 | 1.304 *** | 0.077 | 0.28 | 1.324 *** | 0.078 |

| Am Ind/Alas Native/Haw other PI | −0.183 | 0.833 | 0.386 | −0.194 | 0.823 | 0.386 | −0.197 | 0.821 | 0.386 | −0.20 | 0.819 | 0.386 |

| Asian | 0.216 | 1.241 | 0.231 | 0.267 | 1.306 | 0.231 | 0.21 | 1.234 | 0.231 | 0.25 | 1.284 | 0.232 |

| Black or African American | 0.147 | 1.158 | 0.106 | 0.144 | 1.155 | 0.106 | 0.121 | 1.129 | 0.106 | 0.13 | 0.221 | 0.106 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.018 | 1.018 | 0.089 | 0.032 | 1.033 | 0.090 | 0.009 | 1.009 | 0.089 | 0.023 | 0.796 | 0.090 |

| Multiple races (non-Hispanic) | −0.116 | 0.89 | 0.195 | −0.119 | 0.542 | 0.195 | −0.127 | 0.881 | 0.195 | −0.125 | 0.523 | 0.195 |

| Chi-square | 80.13 | 89.495 | 94.328 | |||||||||

| Log Likelihood | 4871.192 | 4861.826 | 4856.994 | |||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.024 | 0.026 | 0.028 | |||||||||

| Constant | −2.124 | 0.120 *** | 0.083 | −2.267 | 0.104 *** | 0.094 | −2.113 | 0.121 *** | 0.083 | −2.223 | 0.108 *** | 0.098 |

| (Heterosexual Students) | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |||||||||

| β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | |

| Sports team participation | -- | -- | -- | 0.259 | 1.296 *** | 0.075 | -- | -- | -- | 0.456 | 1.578 ** | 0.148 |

| Heterosexual*Sports | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.192 | 1.212 * | 0.087 | -0.265 | 0.767 | 0.172 |

| Heterosexual | −0.644 | 0.525 *** | 0.086 | −0.673 | 0.510 *** | 0.086 | −0.734 | 0.480 *** | 0.095 | −0.563 | 0.569 *** | 0.113 |

| Sex (female) | 0.267 | 1.306 *** | 0.077 | 0.286 | 1.332 *** | 0.077 | 0.282 | 1.326 *** | 0.078 | 0.28 | 1.324 *** | 0.078 |

| Am Ind/Alas Native/Haw other PI | −0.183 | 0.833 | 0.386 | −0.194 | 0.823 | 0.386 | −0.186 | 0.830 | 0.386 | −0.2 | 0.819 | 0.386 |

| Asian | 0.216 | 1.241 | 0.231 | 0.267 | 1.306 | 0.231 | 0.256 | 1.292 | 0.231 | 0.25 | 1.284 | 0.232 |

| Black or African American | 0.147 | 1.158 | 0.106 | 0.144 | 1.155 | 0.106 | 0.155 | 1.168 | 0.106 | 0.13 | 1.139 | 0.106 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.018 | 1.018 | 0.089 | 0.032 | 1.033 | 0.09 | 0.032 | 1.033 | 0.09 | 0.023 | 1.023 | 0.09 |

| Multiple races (non-Hispanic) | −0.116 | 0.89 | 0.195 | −0.119 | 0.542 | 0.195 | −0.114 | 0.893 | 0.195 | −0.125 | 0.883 | 0.195 |

| Chi-square | 80.13 | 91.976 | 84.997 | 94.328 | ||||||||

| Log Likelihood | 4871.192 | 4859.346 | 4866.324 | 4856.994 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.024 | 0.027 | 0.025 | 0.028 | ||||||||

| Constant | −1.48 | 0.228 *** | 0.109 | −1.595 | 0.203 *** | 0.115 | −1.5 | 0.223 *** | 0.110 | −1.659 | 0.190 *** | 0.124 |

| (Transgender Students) | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | |||||||||

| β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | |

| Sports team participation | -- | -- | -- | 0.204 | 1.227 ** | 0.075 | -- | -- | -- | 0.195 | 1.216 * | 0.076 |

| Trans*Sports | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.508 | 1.662 | 0.438 | 0.315 | 1.370 | 0.445 |

| Trans | 1.707 | 5.514 *** | 0.221 | 1.701 | 5.481 *** | 0.221 | 1.458 | 4.298 *** | 0.310 | 1.546 | 4.695 *** | 0.313 |

| Sex (female) | 0.368 | 1.445 *** | 0.076 | 0.388 | 1.474 *** | 0.076 | 0.37 | 1.448 *** | 0.076 | 0.388 | 1.475 *** | 0.077 |

| Am Ind/Alas Native/Haw other PI | −0.174 | 0.841 | 0.387 | −0.184 | 0.832 | 0.388 | −0.193 | 0.824 | 0.389 | −0.196 | 0.822 | 0.390 |

| Asian | 0.161 | 1.174 | 0.233 | 0.203 | 1.225 | 0.233 | 0.156 | 1.169 | 0.233 | 0.198 | 1.219 | 0.234 |

| Black or African American | 0.144 | 1.155 | 0.106 | 0.145 | 1.156 | 0.106 | 0.14 | 1.151 | 0.106 | 0.143 | 1.153 | 0.106 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.037 | 1.037 | 0.089 | 0.051 | 1.052 | 0.090 | 0.035 | 1.036 | 0.089 | 0.049 | 1.05 | 0.090 |

| Multiple races (non-Hispanic) | −0.104 | 0.901 | 0.196 | −0.103 | 0.902 | 0.196 | −0.1 | 0.905 | 0.195 | −0.100 | 0.904 | 0.196 |

| Chi-square | 79.191 | 86.606 | 80.544 | 87.109 | ||||||||

| Log Likelihood | 4872.13 | 4864.716 | 4870.777 | 4864.75 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.023 | 0.025 | 0.024 | 0.026 | ||||||||

| Constant | −2.084 | 0.124 *** | 0.083 | −2.196 | 0.111 *** | 0.093 | −2.084 | 0.124 *** | 0.083 | −2.191 | 0.112 *** | 0.093 |

| (Cisgender Students) | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | Prescription Misuse | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 13 | Model 14 | Model 15 | Model 16 | |||||||||

| β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | β | EXP(B) | SE | |

| Sports team participation | -- | -- | -- | 0.204 | 1.227 ** | 0.075 | -- | -- | -- | 0.510 | 1.666 | 0.439 |

| Cis*Sports | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.195 | 1.215 ** | 0.076 | −0.315 | 0.73 | 0.445 |

| Cisgender | −1.707 | 0.181 *** | 0.221 | −1.701 | 0.182 *** | 0.221 | −1.797 | 0.166 *** | 0.224 | −1.546 | 0.213 *** | 0.313 |

| Sex (female) | 0.368 | 1.445 *** | 0.076 | 0.388 | 1.474 *** | 0.076 | 0.386 | 1.471 *** | 0.076 | 0.388 | 1.475 *** | 0.077 |

| Am Ind/Alas Native/Haw other PI | −0.174 | 0.841 | 0.387 | −0.184 | 0.832 | 0.388 | −0.176 | 0.838 | 0.387 | −0.196 | 0.822 | 0.39 |

| Asian | 0.161 | 1.174 | 0.233 | 0.203 | 1.225 | 0.233 | 0.203 | 1.225 | 0.233 | 0.198 | 1.219 | 0.243 |

| Black or African American | 0.144 | 1.155 | 0.106 | 0.145 | 1.156 | 0.106 | 0.146 | 1.158 | 0.106 | 0.143 | 1.153 | 0.106 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.037 | 1.037 | 0.089 | 0.051 | 1.052 | 0.09 | 0.051 | 1.052 | 0.09 | 0.049 | 1.05 | 0.09 |

| Multiple races (non-Hispanic) | −0.104 | 0.901 | 0.196 | −0.495 | 0.902 | 0.196 | −0.105 | 0.901 | 0.196 | −0.100 | 0.904 | 0.196 |

| Chi-square | 4872.13 | 86.606 | 85.746 | 87.109 | ||||||||

| Log Likelihood | 0.023 | 4864.716 | 4865.576 | 4864.213 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.023 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.026 | ||||||||

| Constant | −0.376 | 0.686 | 0.228 | −0.495 | 0.610 * | 0.233 | −0.394 | 0.674 | 0.229 | −0.645 | 0.525 * | 0.316 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Semprevivo, L.K.; Lopez, V.; Adelman, M.; Lasser, J. The Pitfalls and Promises of Sports Participation and Prescription Drug Misuse Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. Youth 2025, 5, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030077

Semprevivo LK, Lopez V, Adelman M, Lasser J. The Pitfalls and Promises of Sports Participation and Prescription Drug Misuse Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. Youth. 2025; 5(3):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030077

Chicago/Turabian StyleSemprevivo, Lindsay Kahle, Vera Lopez, Madelaine Adelman, and Jon Lasser. 2025. "The Pitfalls and Promises of Sports Participation and Prescription Drug Misuse Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth" Youth 5, no. 3: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030077

APA StyleSemprevivo, L. K., Lopez, V., Adelman, M., & Lasser, J. (2025). The Pitfalls and Promises of Sports Participation and Prescription Drug Misuse Among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. Youth, 5(3), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5030077