Abstract

The global youth mental health crisis is increasingly intertwined with climate change, as young people experience heightened climate anxiety and ecological grief. This study examines the relationship between nature connectedness, climate worry, coping strategies, and mental health outcomes among Canadian university students. Drawing on Pihkala’s process model of eco-anxiety, we propose the Developing Ecological Consciousness Model, a three-act framework that traces young people’s journey from climate awareness to meaningful engagement. Using path analysis on two independent samples (N = 1825), we found that nature connectedness predicts increased climate worry, which in turn correlates with higher levels of depression and anxiety. However, meaning-focused coping emerged as a protective factor, mitigating these negative mental health impacts. Problem-focused coping alone was insufficient, highlighting the need for balanced strategies. The study underscores the dual role of nature connectedness—both as a source of climate distress and a foundation for resilience. These findings highlight the need for interventions that foster ecological consciousness while addressing the emotional toll of climate change, offering insights for policymakers, educators, and mental health practitioners working with youth in a warming world.

1. Introduction

The global crisis of youth mental health has garnered increasing attention in recent years, with numerous studies highlighting the rising prevalence of mental health disorders among young people (McGorry et al., 2024; Benton et al., 2021; Racine et al., 2021). This crisis is exacerbated by various socio-environmental conditions, among which climate change stands out as a significant risk factor. Climate change not only poses direct physical threats but also contributes to psychological stressors that can enhance vulnerabilities among youth. In Canada, the impacts of climate change on mental health are particularly pronounced due to the country’s diverse and rapidly changing environment (Hayes et al., 2019).

Climate anxiety, climate worry, and eco-anxiety have emerged in recent years as new emotional responses that people can experience in relation to climate change (Clayton et al., 2017; Cosh et al., 2024; Betrò, 2024). Climate anxiety is distinct from other forms of general mental health issues due to its existential nature. Unlike generalized anxiety disorders, climate anxiety is rooted in the awareness of long-term environmental changes and the perceived lack of control over these changes (Clayton et al., 2017). This form of anxiety can lead to a range of emotional responses, including feelings of helplessness, grief, and guilt, which are not commonly associated with other types of anxiety (Pihkala, 2020; Smith, 2018).

Given the recent emergence of this mental health phenomenon, scholars are still striving to fully understand the complex interplay of risks and protective factors that influence a young person’s capacity to cope with climate anxiety. For example, studies have examined the sources of climate change information and their influence on people’s perceptions of the issue (Loureiro & Alló, 2020; Cody et al., 2015; Olausson, 2011; O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, 2009; O’Neill et al., 2013), the relationship between climate anxiety and well-being (Hogg et al., 2021; Wullenkord et al., 2021; Clayton & Karazsia, 2020; Helm et al., 2018), the association between climate anxiety and pro-environmental behaviour (Bradley et al., 2020; Ojala, 2012a, 2012b; Hoggett & Randall, 2018), and the relationship between nature connectedness and pro-environmental behaviour (Davis et al., 2009; Mayer & Frantz, 2004; Nisbet et al., 2009; Tam, 2013; Zelenski et al., 2015). Furthermore, factors such as nature connectedness, social support, and community resilience are believed to attenuate the adverse mental health impacts of climate change (Harper et al., 2023).

While research in this field is rapidly growing, a notable gap still exists in the understanding of the process young people undergo when faced with climate change, from the period of their lives when they become aware of this global crisis to when they learn to live with it. Furthermore, in the emerging field of climate emotions, researchers have yet to theoretically address the complex interplay that exists between connection to nature and mental health, especially for individuals who deeply care about the environment. This article aims to address this gap by examining how nature connectedness and mental health are associated with one another among young people who worry about climate change. To achieve our goal, we start from Pihkala’s (2022) process model of eco-anxiety and ecological grief, which provides a framework to guide the current study. Then, we add new dimensions where the model offers opportunities for expansion. Finally, we test the revised framework on two independent samples of Canadian university students and, informed by the results, we conclude by proposing our evidence-informed developmental framework outlaying how young people go from becoming aware about climate change to learning to live with it. We call this developmental framework Developing Ecological Consciousness Model.

In what follows, we start by positioning climate change as a global crisis that has profound implications for young people, posing a threat to their present and future mental health and well-being (Young People and Climate Change; Climate Worry, Eco-Anxiety, and Mental Health). Then, we highlight young people’s capacity to cope with climate change, which requires a combination of strategies, including nature connectedness, emotional awareness, and community cohesion (Coping with Climate Worry). In the following section, we unpack Pihkala’s (2022) process model of eco-anxiety and ecological grief and justify the need for expansion and empirical testing of this model (Beyond a process model of eco-anxiety). Next, we describe the methods (Methods) and results (Results) of our study, followed by outlining the key features of our evidence-informed developmental framework (Developing Ecological Consciousness Model). We end the paper addressing limitations and sharing concluding remarks.

1.1. Young People and Climate Change

The impending threat of climate change is becoming increasingly urgent as it significantly impacts people’s psychological well-being (Doherty & Clayton, 2011; Swim et al., 2011). The United Nations (UN, 2018) defines climate change as the prolonged changes in weather patterns and temperatures globally, primarily attributed to human activities such as the burning of fossil fuels and emissions of greenhouse gases. The physical and mental health outcomes of both short-term and long-term environmental changes are concerning, including increased anxiety and mood disorders, acute stress reactions, post-traumatic stress disorders, elevated violence and conflicts, higher rates of drug and alcohol abuse, and intense emotional responses such as despair, fear, helplessness, and suicidal ideation (Berry, 2009; Berry et al., 2010; Coyle & Van Susteren, 2012; Doherty & Clayton, 2011; Fritze et al., 2008; Page & Howard, 2010; Stanke et al., 2012; Swim et al., 2011).

Climate change poses a severe threat to the younger generation. The youth of today grow up with feelings of uncertainty and unprecedented fear regarding their future (Clayton et al., 2017; Watts et al., 2019; UN, 2018). The 2019 Lancet Health and Climate Change report showcases several physical health risks affecting youth if the climate problem is not addressed promptly. However, even though this demographic group will make decisions in the future and be left to deal with the effects of the changing environment, research often ignores the influence of climate change on their mental health (Fritze et al., 2008; Clayton & Manning, 2018; Ojala, 2012a, 2012b; Ojala & Bengtsson, 2019).

Few review studies emphasize that young people are more likely to be disproportionately affected by the mental health impacts of climate change to adults (Charlson et al., 2021; Clemens et al., 2020). Recent evidence highlights that a significant proportion of young people in different parts of the world are experiencing high levels of anxiety and fear about the planet’s future (Léger-Goodes et al., 2022; Hickman et al., 2021). For example, an extensive study by Hickman et al. (2021) surveyed youth from 10 nations and found that 60% of young people report worry, sadness, fear, and anxiety due to climate change.

Moreover, a particularly alarming finding was that 75% of respondents feel that the future is frightening, highlighting the profound impact climate change can have on young people’s mental health and well-being. Similarly, other studies discovered that 89% of Australian youth and 74% of British youth worry about the effects of climate change (Chiw & Shen Ling, 2019; UNICEF United Kingdom (UK), 2013). According to surveys in the United States, 70% of the respondents reported that they are “somewhat” or “extremely” worried about global warming (Leiserowitz et al., 2021), and 82% of young people in the United States also report feelings of fear, sadness, and anger regarding climate change (Strife, 2012).

This phenomenon is also observed in Canada where over 70% of Canadian youth reported feeling worried and frustrated (Galway & Beery, 2022), and a range of emotions, including fear (66%), sadness (65%), anxiety (63%), helplessness (58%), and powerlessness (56%) about climate change (Galway & Field, 2023). Similarly, Maggi et al. (2023) found that a sample of Canadian university students frequently experienced overwhelming emotions when thinking about climate change, such as sadness (77%), fear (77%), anxiety (73%), helplessness (79%), guilt (73%), shame (69%), and anger (67%). Furthermore, 80% of these young people expressed being very or somewhat concerned about climate change and about 81% reported feeling worried about the detrimental impacts of climate change on nature and future generations.

The studies presented so far demonstrate the reactions of youth across the globe toward climate change. Their emotional responses and the potential threat they pose to their mental health underscore the urgency of addressing this issue and emphasize the pressing need for immediate measures to reduce carbon emissions, restore ecosystemic balance, and mitigate the impacts of climate change on people and the more-than-human world. Meanwhile, scholars can continue to contribute to just and equitable climate solutions by building a theory and data-driven knowledge base about young people’s efforts to stay engaged with the climate crisis while taking care of themselves.

1.2. Climate Worry, Eco-Anxiety, and Mental Health

Over the years, scholars have engaged in ongoing discussions about the emergent phenomenon of “eco-anxiety” which is characterized as a complex emotional state that grows as people’s understanding about climate change increases, and the anticipation of future climate events and concerns about their impacts are contemplated (Fritze et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2023; Ágoston et al., 2022; Clayton, 2020).

Worry and anxiety are among the most common psychological responses to potential future climate-related events (Charlson et al., 2021, 2022). As defined by Stewart (2021), climate change worry refers to troubling concerns about climate change that may lead to the experience of negative thoughts and feelings surrounding the issue. This worry is an expected and understandable response, which can also motivate individuals to act on climate-related issues (Verplanken & Roy, 2013; Verplanken et al., 2020; Berry & Peel, 2015; Pihkala, 2022).

According to Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002), pro-environmental behaviours are conscious actions one performs to minimize the negative impact of their behaviour on the environment, and Pihkala (2022) proposes that there is a need to comprehend how these emotions work together to initiate pro-environmental behaviour and climate action. A notable distinction to consider is between practical anxiety and general trait anxiety. Kurth and Pihkala (2022) explain that eco-anxiety can manifest as “practical anxiety,” which alerts us to the uncertainty of our situation and prompts information-gathering behaviours to resolve the issue. Similarly, several scholars have found that climate worry can also take the form of practical anxiety, motivating people to take action (Curll et al., 2022; Stewart et al., 2023; Kurth & Pihkala, 2022).

Despite eco-anxiety being an emerging concept, studies have shown that it is not strongly correlated with general trait anxiety. For example, Hogg et al.’s (2021) empirical investigation with undergraduate students highlighted that eco-anxiety is a unique construct, distinct from general anxiety. Additionally, a study conducted in the UK found no relationship between climate change worry and pathological worry (Verplanken & Roy, 2013). Similarly, Australian researchers found weak associations between climate emotions and low well-being, with insignificant correlations with general anxiety and depression (Helm et al., 2018). Klöckner et al. (2009) also found no association between worry, anxiety, and guilt about climate change and well-being in their sample of young people. These findings suggest that while climate worry and eco-anxiety can serve as practical motivators for action, they remain distinct from general anxiety and other emotional responses.

However, as this field of research is relatively new, there are some conflicting findings regarding the distinction between eco-anxiety and clinically significant mental health issues. Given the intricate nature of climate change, eco-anxiety does have the potential to manifest in maladaptive and immobilizing forms (Kurth & Pihkala, 2022; Clayton, 2020; Mosquera & Jylhä, 2022). For instance, in the United States, researchers have identified significant correlations between generalized depression and anxiety, climate anxiety (Clayton & Karazsia, 2020), and eco-stress (Helm et al., 2018; Budziszewska & Kałwak, 2022). Also, studies in the UK (Whitmarsh et al., 2022) and Germany (Wullenkord et al., 2021) reported similar results. Notably, younger adults report higher scores than older adults when asked about the degree to which climate anxiety impacts their ability to carry out their day-to-day tasks (Clayton & Karazsia, 2020). For example, a study on Swedish youth revealed a significant negative relationship between climate worry and well-being (Ojala, 2005) and Clayton (2020) highlighted that children are more vulnerable to climate change’s mental health effects as they respond more to extreme weather events.

These associations might be influenced by the scales used to assess pathological aspects of these emotions. For example, the Climate Change Anxiety Scale developed by Clayton and Karazsia (2020) measures the extent to which climate anxiety negatively affects daily functioning and mental health. Overall, the literature suggests that if these emotions become too intense and difficult to handle, they may reach clinically significant levels (Burke et al., 2018; Clayton & Karazsia, 2020; Ogunbode et al., 2021). Some studies have demonstrated that difficult-to-manage climate change anxiety can adversely affect well-being and diminish the quality of life (Stanley et al., 2021; Salas Reyes et al., 2021). That said, several studies reveal that only a small portion of people experience clinical levels of eco-anxiety (Berry & Peel, 2015; Clayton & Karazsia, 2020; Ogunbode et al., 2021; Wullenkord et al., 2021) which are associated with impaired cognitive abilities and reduced capacity for carrying out day-to-day tasks.

Kurth and Pihkala (2022) argue that our understanding of eco-anxiety, its significance, and its impact on mental well-being can become distorted when we excessively focus on the rare, pathological manifestations of this emotion. The clinical forms of eco-anxiety observed in a small number of individuals may not accurately represent the typical emotional experiences of young people in the general population (Lawton, 2019; Kurth & Pihkala, 2022). When recognizing that worry and anxiety are natural responses to perceived threats, it becomes crucial to understand how young people can maintain a long-term engagement with climate change without encountering significant mental health challenges.

1.3. Coping with Climate Worry and Other Climate Emotions

Young people may employ various coping styles to navigate the psychological stress and anxiety that arises due to climate change. According to Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) stress and coping theory, coping refers to behavioural actions people undergo when confronted with different psychological stress and threats, and climate change represents one such challenge. In this section we review four approaches of relevance to coping with climate change: nature connectedness, problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping, and meaning focused coping.

1.3.1. Nature Connectedness

In the context of the climate crisis, a meaningful connection with the natural world is crucial. To effectively contribute to preserving the biosphere and restoring planetary health, young people require opportunities to meaningfully engage with nature. As said by Attenborough (2015), “If children grow up not knowing about nature and appreciating it, they will not understand it, and if they don’t understand it, they won’t protect it, and if they don’t protect it, who will?”

Nature connectedness—the subjective sense of being emotionally, cognitively, and spiritually bonded with the natural world—is not a universal experience, but is instead shaped by complex developmental, cultural, and environmental factors (Lumber et al., 2017). For some individuals, early life experiences in nature, supportive caregivers who model environmental concern, and cultural practices that honour ecological relationships play foundational roles in fostering a strong connection to nature (Chawla & Gould, 2020; Tam, 2013). Access to safe and biodiverse outdoor environments also significantly increases the likelihood of developing nature connectedness (Richardson et al., 2020). Conversely, urbanization, socio-economic barriers, and cultural disconnection from land—particularly in settler colonial contexts—may limit opportunities to form such bonds. These differences in lived experience and ecological exposure help explain why some individuals cultivate deep ecological consciousness while others remain detached.

Of the many challenges posed by climate change, its impact on the natural world is of great concern for younger generations, especially among those who feel close to nature. Climate change amplifies worries about the future of the planet and the more-than-human world. Recent studies have demonstrated that people with a stronger connection to nature are more likely to worry about the effects of climate change (Curll et al., 2022; Thomson & Roach, 2023) and that nature connectedness may be associated with poor mental health outcomes in the context of the climate crisis (Dean & Green, 2018; Curll et al., 2022; Thomson & Roach, 2023). For example, Curll et al. (2022) found that after a season of forest fires, people who had a stronger connection to nature reported higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. Similarly, Dean and Green (2018) found that people with a stronger connection to nature were more likely to experience psychological distress after a major flood. Curll et al. (2022) also found similar findings but only for individuals who worried about climate change in the first place.

The relationship between climate worry, nature connectedness and mental health, however, is complex. It is important to recognize that nature connectedness can also serve as an effective coping mechanism for existential worry, such as climate worry, enabling young people to preserve their connection to the natural world while, at the same time, acting as a motivator to take proactive steps in addressing the climate crisis.

Overall, nature connectedness seems to play a pivotal role as a precursor for climate worry, which serves as a crucial catalyst to motivate young people towards action (Curll et al., 2022; Thomson & Roach, 2023). In fact, empirical studies have consistently found nature connectedness and relatedness to be significant predictors of pro-environmental behaviour (Davis et al., 2009; Mayer & Frantz, 2004; Nisbet et al., 2009; Tam, 2013; Zelenski et al., 2015). The literature shows that young people with a strong connection to nature have greater environmental knowledge, a greater willingness to conserve nature (Otto & Pensini, 2017), and report more pro-environmental behaviours (Hughes et al., 2018), which is consistent with studies on adult populations.

In a meta-analysis that included grey literature and null studies to eliminate publication bias, the authors reported a significant and positive estimated mean correlation of r = 0.37 (Mackay & Schmidtt, 2019). In line with the current population of interest, the estimated mean correlation between nature connection and pro-environmental behaviour in university samples is r = 0.41. In experimental studies, the estimated mean effect size across studies was significant and positive (d = 0.21) (Mackay & Schmidtt, 2019). After finding strong correlational evidence, Davis et al. (2009) conducted an experimental study in which they primed undergraduate students to feel either high or low commitment to the environment. Participants were randomly assigned to complete a writing task designed to activate either feelings of connection and dependence on nature (e.g., describing how the natural environment benefits them), or feelings of disconnection and independence from nature (e.g., listing daily actions believed to have no environmental impact). This priming was presented as part of an unrelated study to reduce bias. Results showed that participants in the high-commitment condition reported significantly greater pro-environmental intentions and behaviours than those in the low-commitment condition, supporting a causal link between nature connectedness and climate action.

From these studies, it can be argued that connecting with nature serves a dual purpose in the context of climate change: it not only prompts young people to worry about the effects of climate change, but it also motivates them to take action to mitigate its impact on the planet.

1.3.2. Problem Focused Coping

In this type of coping style, the main goal is to face the problem head-on and look for ways to eliminate the cause of the stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Arguably, this is perhaps the most common approach among young people who are concerned about climate change, and it translates into all sorts of actions, from individual pro-environmental behaviours to different levels of engagement with activism. For example, scholars have found that participating in pro-environmental behaviour can be a coping strategy for eco-anxiety (Bradley et al., 2020). Taking action, and often urgent action, is one of the most common suggestions for coping with eco-anxiety. For example, in an interview for The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, 2019), Greta Thunberg states, “Act. Do something. Because that is the best medicine against sadness and depression.” Following that interview, many environmental bloggers and journalists wrote to their readers about the power of activism in coping with climate despair (for example, see Marris, 2020; Yoder, 2021).

However, problem-focused coping in the context of climate change could act as a double-edged sword, because this approach positively influences mental well-being when applied toward the solution of micro-level problems (Clarke, 2006; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), but it fails to do so for a polycrisis like climate change (Hallis & Slone, 1999; Heyman et al., 2010). Furthermore, engaging in pro-environmental behaviour may offer temporary relief from eco-anxiety and ecological grief (Bradley et al., 2020); however, scholars emphasize the need for emotional hardiness alongside action to prevent burnout (Davenport, 2017; Pihkala, 2020). For example, Ojala (2012a, 2012b) revealed that the more the young people relied on problem-focused coping strategies to deal with climate change, the more likely they were to experience challenging emotions, such as anxiety. Clayton (2020) also highlights that problem-focused coping might be ineffective in dealing with climate change due to its vastness. Therefore, prolonged use of this strategy can lead to more significant distress. Lastly, engaging in problem-focused coping can evoke greater worry about climate change and amplify symptoms of anxiety and depression among young people, as they have less control over their actions concerning climate change (Ojala, 2012a).

1.3.3. Emotion-Focused Coping

In contrast to problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping strategies aim to alleviate the emotions associated with the stressor through methods like avoidance and distancing (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Research consistently demonstrates that while these strategies may temporarily reduce emotional distress, they can have negative consequences for overall well-being in the long term (Frydenberg, 2008). For example, Ojala (2012b) found that some participants in her studies reported minimizing the importance of climate change and perceiving the media’s portrayal of this phenomenon as an exaggeration of the threat. Participants also occasionally displayed psychological distancing from the problem as another way to cope with climate change. For instance, participants reported actively avoiding information related to the climate crisis, such as refraining from watching the news and other forms of media. Ojala (2012a) highlighted that the more de-emphasizing young people used to cope with climate change, the less likely they were to feel depressed or anxious. However, young people who solely use emotion-focused strategies also report being less engaged with climate action. This is expected, because while emotion-focused coping may relieve anxious feelings, it does so by temporarily ‘putting aside’ the source of the problem instead of addressing it and actively contributing to its resolution.

1.3.4. Meaning-Focused Coping

An approach that encompasses elements of both problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping, along with strategies that emphasize the importance of finding meaning and purpose amidst this significant challenge, is meaning-focused coping (Folkman, 2008). Research has shown that meaning-focused coping is an appropriate strategy when the stressor cannot be easily removed or solved, but it still demands our involvement (Folkman, 2008; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000), which is the case for climate change.

In the face of this global crisis, young people confront existential questions surrounding meaninglessness, responsibility, guilt, and death anxiety (Budziszewska & Jonsson, 2021; Passmore et al., 2022; Pienaar, 2011; Pihkala, 2018). As strong eco-anxiety often evokes feelings of meaninglessness (Macy & Johnstone, 2012; Jamail, 2020), fostering a sense of purpose in the world becomes crucial. Ultimately, this coping style involves strategies that aim to foster a sense of meaning and resilience in the face of climate change. Meaning-focused coping strategies involve cultivating uplifting emotions amidst experiences of complex and challenging emotions like eco-anxiety and ecological guilt, adopting alternative perspectives that emphasize one’s capacity to address environmental issues, practicing mindfulness and connecting with nature, and engaging with spiritual practices.

Young people who use meaning-focused coping strategies demonstrate the capacity to cultivate positive emotions (i.e., hope, optimism, and motivation) even when they are experiencing eco-anxiety and ecological grief (Ojala, 2012b). According to Fredrickson (2001), individuals should attempt to cultivate positive emotions to achieve long-term well-being. Her broaden-and-build theory states that positive emotions have the ability to broaden peoples’ thought-action processes and build the endurance of personal resources (Fredrickson, 1998). Furthermore, positive emotions can protect against the adverse mental health effects of eco-anxiety and ecological grief (Hicks & Holden, 2007; Ojala, 2005).

Likewise, Ojala (2012a) found that young people who use meaning-focused strategies to cope with climate change had more positive emotions and fewer feelings of anxiety. Like Ojala (2012a), Clayton (2020) also highlights that when children engage in meaning-focused coping strategies to cope with climate change, they tend to experience fewer challenging emotions, including anxiety. In line with these scholars, Ágoston et al. (2022) also found that using meaning-focused strategies to cope with eco-anxiety is more adaptive than using problem-focused strategies.

In conclusion, the coping strategies discussed in this section provide valuable insights into managing climate worry and eco-anxiety. The existing research on coping with climate change has predominantly focused on examining the effectiveness of specific coping styles in isolation, leading to a fragmented understanding of their relationship with pro-environmental behaviours and mental health. This segregation of coping strategies, such as problem-focused, emotion-focused, and meaning-focused, limits our comprehensive understanding of their combined effects in addressing the complex challenges posed by climate change.

To address this issue, Pihkala (2022) introduced a theoretical framework for coping with climate change. This framework, which this study is guided by, is presented next.

1.4. A Process Model of Eco-Anxiety

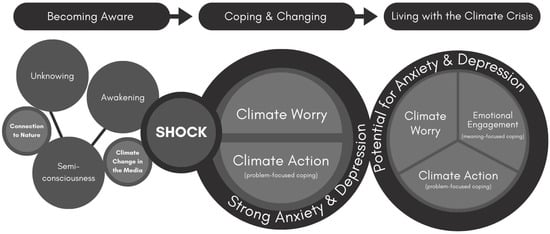

Pihkala’s (2022) model of eco-anxiety and ecological grief envisions three moments that characterize how young people process the emotional impacts of climate change.

At the beginning, the early phase of the model includes the period of “Unknowing” which is conceptualized by the author as relatively short, particularly in today’s digital age, where technology and media play a prominent role in the lives of young people. In fact, research indicates that the influence of scientific information on public opinion regarding climate change has little effect compared to the impact of media sources (Brulle et al., 2012; Chapman et al., 2017), and while television remains the most commonly used source for information across all age groups, young people tend to rely more on social media and blogs to learn about climate change (Andi, 2021; Parry et al., 2022). Notably, individuals between the ages of 18 and 24 are three times more likely to seek climate change news from celebrities and social media influencers compared to older adults (Andi, 2021). To illustrate this, one high school student aptly articulates, “I feel like social media is the best way to spread information about this topic [climate change] to our generation, I can’t think of anyone who watches the news like our parents” (Prothero, 2023).

The widespread accessibility of climate change content through digital platforms highlights the influential power of media portrayals in shaping attitudes and perceptions towards the climate crisis (Maran & Begotti, 2021; Olausson, 2011; Parry et al., 2022). For example, in Olausson’s (2011) study, when asked to associate climate change with a specific image, many participants immediately thought of polar bears, a symbolic representation widely popularized by media outlets for several decades.

Climate change, as well as seeing the effects of climate change unfold through the media, may threaten a young person’s connection to nature and as discussed earlier, their mental health (Dean & Green, 2018; Curll et al., 2022; Thomson & Roach, 2023). In other words, the combination of witnessing climate change unfolds through the media for people who have a strong connection to nature potentially accelerates the progression to “Semiconsciousness” and “Awakening”, the two subsequent periods that characterize Pihkala’s model early phase.

Following the Awakening, which for some can be a shocking and traumatic experience, some individuals may choose to distance themselves from the issue while others may swiftly transition into engaging with climate action, propelled by the desire to resolve the climate crisis and eliminate the cause of their discomfort. For example, recent studies have demonstrated that people with a stronger connection to nature are more likely to worry about the effects of climate change, and in turn, are more willing to act on the problem (Curll et al., 2022; Thomson & Roach, 2023). However, as pointed out earlier, research has also found associations between nature connectedness and poor mental health outcomes in several climate change studies (Dean & Green, 2018; Curll et al., 2022; Thomson & Roach, 2023). When young people find themselves in this scenario, they are entering the “Coping and Changing” phase of Pihkala’s model. The combination of a strong connection to nature, existential worries and anxieties about the climate crisis, and the perceived difficulties in coping with these emotional challenges may result in strong anxiety and depression (Pihkala, 2022), impeding young people’s ability to progress toward the final phase of “Living with the Ecological Crisis”, which they enter only once they have overcome their difficulties.

Pihkala’s (2022) model provides valuable theoretical insights about the overall process that young people may experience from becoming aware of climate change to learning to live with this polycrisis. At the same time, this framework offers opportunities for expansion. For example, in the initial phase, “Unknowing” and “Semiconsciousness” are recognized as pivotal moments where eco-anxiety often emerges and intensifies. However, little is provided in terms of the mechanisms and processes that underline the progression of climate worry and eco-anxiety during these key early stages. This limitation is then carried throughout the rest of the model where the processes described lack integration with relevant developmental theories. However, to better understand how these processes unfold in the context of the development of the young person is key for advancing knowledge in this field and to build robust theory-driven models.

Therefore, our study aims at extending Pihkala’s (2022) model by adding a key dimension which is currently missing, nature connectedness. Furthermore, we aim at empirically testing the model on two independent samples of Canadian university students to determine the role that nature connectedness plays in the process model of eco-anxiety and ecological grief. Ultimately this study will help fill a gap in current knowledge by revealing how nature connectedness and mental health are associated with one another among young people who worry about climate change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Positionality Statement

McKenna Corvello: I am a white, cisgender woman and settler living on the traditional territories of Indigenous peoples in Canada. As a developmental scientist and youth mental health advocate, I bring a lens shaped by both academic training and frontline experience with young people navigating intersecting systemic challenges. My work is informed by a commitment to climate and social justice, and a belief in the importance of meaning, purpose, and emotional engagement in the lives of youth. I recognize the privileges I hold and continually reflect on how they shape my research perspective, particularly when working alongside equity-seeking communities. I am guided by an ecological and relational worldview that centres youth voices, honours lived experience and embraces complexity in understanding climate change and mental health.

Cerine Benomar: I am a cisgender, first-generation immigrant woman whose multicultural upbringing has shaped a diverse and inclusive perspective in my work as an analytical contributor to this project. I recognize that data reflects complex human experiences, and I am committed to integrating demographic awareness and diverse viewpoints into my approach.

Stefania Maggi: As a white, cisgender Italian immigrant with both privilege and lived experience of an invisible disability, I navigate intersecting positions of advantage and marginalization that shape my research lens. Grounded in critical realism (ontology) and contextualism (epistemology), I recognize structural forces while valuing situated knowledge and lived experience. My interdisciplinary background in developmental sciences, population health, participatory action research, and children’s rights advocacy informs my commitment to equity-driven, co-created scholarship. I leverage my privileges to challenge systemic inequities while centering youth voices, critically reflecting on how my identity influences interpretation and power dynamics in research.

2.2. Procedure and Participant Characteristics

Participants in this study consists of students enrolled in first- and second-year psychology courses at a Canadian university. Students were recruited in two waves through SONA, a recruitment platform, and were then redirected to complete the survey online on Qualtrics. Participants were recruited during the fall semester of 2021 (Wave One) and the fall semester of 2022 and winter semester of 2023 (Wave Two). The initial sample for Wave One included 992 participants and the initial sample for Wave Two included 1139 participants. In Wave One, after excluding those who did not complete the survey (n = 73) and those with missing and ‘other’ gender responses (n = 22), a sample of 897 was retained. In Wave Two, after excluding those who did not complete the survey (n = 110) and those with missing and ‘other’ gender responses (n = 40), a sample of 989 was retained. Cases with high leverage values and those outside +/−2 standard deviations away from the mean were removed, leaving a final sample of 871 participants in Wave One, and 954 participants in Wave Two for the main analysis. For both waves, mean age of participants was 19 (Wave One: M = 19.67, SD = 3.08; Wave Two: M = 19.38, SD = 2.92). The gender distribution was similar across waves: in Wave One, 72.6% identified as female and 25.0% as male; in Wave Two, 70.9% identified as female and 29.1% as male (for a full sample description on the Wave One cohort see Maggi et al., 2023). Ethics approval was obtained from the University Research Ethics Board (Clearance #116016, #117839, #118758).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Mental Health Outcomes

Two constructs were used to measure mental health outcomes: generalized depression and generalized anxiety (see Appendix E and Appendix F). Generalized Depression includes 12 depressive symptoms from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977; Poulin et al., 2005). Symptoms included “I had crying spells” or “My sleep was restless” which were rated on a four-point scale: 0 = “Rarely or none of the time—less than 1 day” to 3 = “Most or all of the time—5 to 7 days”. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency in Wave One (a = 0.84) and Wave Two (a = 0.81).

Generalized Anxiety was measured using six items from the Generalized Anxiety Disorder subscale from the Ontario Child Health Study Emotional Behavioural Scale (OCHS-EBS; Duncan et al., 2019). Sample prompts include “I am too fearful or anxious” and “I worry about doing better at things” that were evaluated on a three-point scale: 0 = “Never or not true” to 2 = “Often or very true”. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (a = 0.86) in Wave One and (a = 0.85) in Wave Two.

2.3.2. Connectedness to Nature Scale

Nature connectedness was assessed using 14 items from the Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) (Mayer & Frantz, 2004; see Appendix B). Items include “I often feel a sense of oneness with the natural world around me” and “I often feel a kinship with animals and plants” that were evaluated on a three-point scale in wave one: 1 = “Disagree” to 3 = “Agree” and on a five-point scale in wave two: 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”. Three items “When I think of my place on Earth, I consider myself to be a top member of a hierarchy that exists in nature”, “My personal welfare is independent of the welfare of the natural world”, and “I often feel disconnected from nature” were excluded to enhance the reliability of the scale (Navarro et al., 2017). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (a = 0.90) in Wave One and (a = 0.91) in Wave Two. The CNS was developed to capture the emotional and experiential dimensions of individuals’ relationships with the natural world (Mayer & Frantz, 2004). It is widely used in environmental psychology and has demonstrated good reliability and predictive validity across populations (Tam, 2013). The scale is grounded in the theoretical assumption that connectedness is not simply about time spent in nature, but about a sense of oneness, empathy, and care for non-human life. We adapted the original 14-item CNS, excluding three items that have previously shown lower reliability in university-aged populations (Navarro et al., 2017), and tailored response formats to align with the overall structure of our longitudinal study. Our version retained strong internal consistency, and items such as “I often feel a kinship with animals and plants” align closely with the affective and identity-based dimensions central to our theoretical model of ecological consciousness.

2.3.3. Climate Change Worry Scale

The climate change worry scale (Ojala, 2012a; see Appendix C) consists of five items that aim to assess the degree of worry due to negative consequences caused by climate change. Sample items include “I worry that I myself will be negatively affected by climate change” and “I am concerned that people living in poor countries will be negatively affected by climate change” that were evaluated on a three-point Likert scale in Wave 1: 1 = “Disagree” to 3 = “Agree” and on a five-point Likert scale in Wave 2: 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (a = 0.85) in Wave One and (a = 0.92) in Wave Two.

2.3.4. Coping with Climate Change Scale

The coping scale (Ojala, 2012a; see Appendix D) aimed to assess the degree of how youth cope with climate change through three strategies: problem-focused coping, meaning-focused coping, and emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused coping consists of three items “I think about what I myself can do to improve climate issues”, meaning-focused coping consists of six items “I have faith in people involved in environmental organizations”, emotion-focused coping consists of six items “I cannot be bothered to worry about the climate issue”. Two subscales from the coping scale were used: problem-focused coping and meaning-focused coping. One item “I have trust in politicians to solve the climate change problem” from the meaning-focused coping subscale was excluded due to low item-total correlation. Items were evaluated on a three-point Likert scale in Wave 1: 1 = “Disagree” to 3 = “Agree” and on a five-point Likert scale in Wave 2: 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”. The problem-focused coping subscale demonstrated good internal consistency (a = 0.80) in Wave One and (a = 0.85) in Wave Two. The meaning-focused coping subscale demonstrated good internal consistency (a = 0.73) in Wave One and (a = 0.76) in Wave Two.

This study included only the problem-focused and meaning-focused coping subscales, excluding emotion-focused coping. This decision reflects prior research showing that emotion-focused coping strategies—such as avoidance, denial, or distancing—may reduce distress in the short term but often hinder sustained engagement with climate change (Ojala, 2012a, 2012b). Since our primary aim was to explore coping strategies that support both psychological well-being and ongoing climate action, emotion-focused coping was considered less aligned with these goals. In contrast, problem-focused (action-oriented) and meaning-focused (purpose-driven) approaches are more likely to foster resilience while encouraging constructive responses to climate change. Limiting our focus to these two coping strategies helps ensure the model emphasizes adaptive, engagement-promoting forms of coping that are most relevant to young people navigating climate distress.

2.3.5. Knowledge About Climate Change

The following prompt was presented, “What sources do you rely on for information about climate change (please choose the three that you rely on the most)” to measure the primary mediums through which participants acquire knowledge about climate change (see Appendix A).

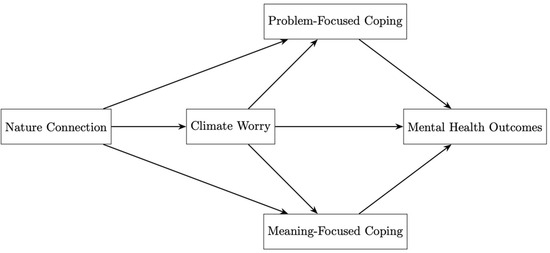

2.4. Analytic Strategy

All statistical analyses in this study were conducted in R (Version 4.3.3; R Core Team, 2024). First, frequency analyses on both waves were used to determine whether young people primarily obtain information about climate change through the media. Next, given the exploratory nature of this study and the novelty of Pihkala’s (2022) model, no specific directional hypotheses were formulated a priori. Instead, path analyses were performed to illuminate the different ways in which nature connectedness, climate worry, and coping strategies affect mental health using the sem () function in the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012). Using Pihkala’s (2022) model as a guiding framework, theoretical and statistical representations of the proposed model for the present study are depicted below (Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively). Gender was included as an additional exogenous variable to control for its effects, and the residual variances were allowed to correlate between problem-focused coping and meaning-focused coping. To ensure the robustness and generalizability of the model, the results from Wave One were subjected to replication using survey data from Wave Two. Acceptable model fit was evaluated as comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) > 0.90, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.08 (Kline, 2005).

Figure 1.

A theoretical representation of the proposed expanded process model tested in the present study.

Figure 2.

Statistical representation of expanded process model tested in present study.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives

Table 1 displays the frequency of participants who selected their top sources for obtaining information on climate change. We expected that, in accordance with the literature, most young people across the two waves of data collection would primarily rely on social media for information on climate change. This expectation was confirmed: social media emerged as the top information source at each data collection point. The frequency of participants selecting social media was about 10% higher compared to the second most selected sources—documentaries and podcasts, blogs, and news from environmental organizations—in both waves.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for both waves on the information sources variable.

Table 2 displays the descriptive and correlational analysis for all measures used in the analysis.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix and descriptive statistics for main variables at Wave One and Wave Two.

3.2. Path Analysis

Table 3 displays standardized regression coefficients from the path analysis examining the effects of nature connection, climate worry, problem-focused coping, and meaning-focused coping with generalized anxiety and generalized depression as outcome variables using samples from Wave One and Wave Two.

Table 3.

Path analysis results at wave one and wave two.

Nature connection exhibited a significant and positive relationship with climate worry (Wave One: B = 0.13, p < 0.001; Wave Two: B = 0.23, p < 0.001), indicating that young people who were more connected to nature were more likely to experience heightened worry about climate change. Nature connection also positively influenced the use of both problem-focused coping (Wave One: B = 0.12, p < 0.001; Wave Two: B = 0.10, p < 0.001) and meaning-focused coping (Wave One: B = 0.10, p < 0.001; Wave Two: B = 0.09, p < 0.001) strategies. This suggests that young people with a strong connection to nature were more likely to engage in both problem-focused and meaning-focused strategies when coping with climate change. Climate worry was also a significant predictor for adopting coping strategies. Young people who experienced greater worry about climate change were more likely to engage in problem-focused coping (Wave One: B = 0.21, p < 0.001; Wave Two: B = 0.13, p < 0.001) and meaning-focused coping (Wave One: B = 0.23, p < 0.001; Wave Two: B = 0.11, p < 0.001) strategies.

Climate worry had a positive and significant effect on generalized depression (Wave One: B = 0.25, p = 0.03; Wave Two: B = 0.19, p < 0.001), indicating that young people who were worried about climate change were more likely to experience higher levels of generalized depression. Meaning-focused coping had a negative and significant effect on generalized depression (Wave One: B = −0.70, p < 0.001; Wave Two: B = −0.23, p < 0.001), indicating that those who experienced meaning-focused coping strategies were less likely to feel depressed.

Climate worry had a positive and significant effect on generalized anxiety (Wave One: B = 0.22, p < 0.001; Wave Two: B = 0.12, p < 0.001), indicating that young people who were worried about climate change were more likely to experience higher levels of generalized anxiety. Meaning-focused coping had a negative and significant effect on generalized anxiety in Wave One (Wave One: B = −0.14, p < 0.01), indicating that those who experienced meaning-focused coping strategies were less likely to feel anxious.

The standardized indirect effects revealed that the effects of nature connection on generalized anxiety and generalized depression were significantly mediated by climate worry. The effects of nature connection on generalized anxiety and depression were also significantly mediated by both climate worry and meaning-focused coping in Wave One. The effect of nature connection on both coping strategies was also significantly mediated by climate worry.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Developing Ecological Consciousness Model

This study aimed to empirically examine Pihkala’s (2022) process model, with the important addition of nature connectedness, to more accurately represent the journey that young people who worry about climate change undergo during the climate crisis. We also examined the role that different types of sources of climate change information played in the early phase of Pihkala’s (2022) process model. In what follows, we introduce the Developing Ecological Consciousness Model and discuss how it departs from Pihkala’s process model. This model is based on the results of the present study, but it also incorporates empirical evidence from the broader published literature that supports its tenets. Through this discussion, we aim to spark meaningful debate and foster scholarly dialogue on this important and emerging field of research, rather than advancing a fixed or definitive perspective.

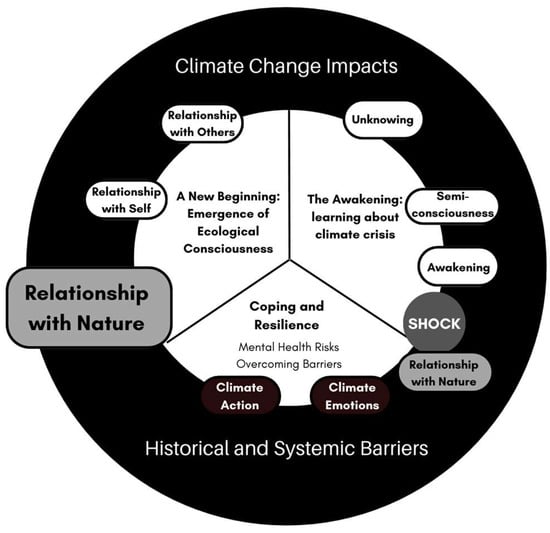

The Developing Ecological Consciousness Model (Figure 3) is organized around a three-act structure inspired by the hero’s journey metaphor (Campbell, 2014).

Figure 3.

Developing Ecological Consciousness Model.

This choice will invite valid critiques. For example, the hero’s journey archetype represents an anthropocentric view of the world that has been acknowledged as one of the primary causes of the environmental crisis (Tokay, 2023); the use of “hero” in its singular form can risk overemphasizing individual responsibility, potentially obscuring the collective and relational nature of climate action; originally rooted in Western, male-centric narratives (Hambly, 2021), the hero’s journey metaphor may not resonate across all cultural frameworks or lived experiences, especially those where humans are seen as inseparable from ecological networks. These critiques are important, and we do not intend to suggest that climate transformation rests on individual shoulders, nor that there is a singular, universal path to ecological awakening, or that a hierarchical life system exists with human beings at the top.

Rather, we choose to adopt the hero’s journey metaphor because it offers a relatable and compelling narrative arc that can help illustrate how young people move from initial unawareness of the climate crisis, through emotional upheaval and self-reflection, to the emergence of a more grounded and active ecological consciousness. Importantly, recent research supports the psychological value of framing personal experiences through this lens. Rogers et al. (2023) found that when people perceive their lives as reflecting the structure of a hero’s journey—defined by elements such as challenge, transformation, and legacy—they report a stronger sense of meaning in life and greater psychological resilience. This effect persisted across diverse samples and was shown to be causally influenced by a “restorying” intervention that helped individuals reframe their life narratives in alignment with this archetype.

Furthermore, in our model, the “hero” is not a lone saviour, but a symbol of both inner growth and collective transformation. As Gandhi observed, “A true hero is not defined by their strength, but by their ability to inspire and lead others.” We view heroism as accessible and relational—embodied by anyone who chooses to feel, grow, and act in response to climate-related challenges.

Therefore, we adopt the hero’s journey metaphor to the extent that it offers a relatable and familiar structure for describing a complex process of growth and development. We do not, however, support the anthropocentric and individualistic views that this metaphor represents in its original form.

With that in mind, our model unfolds over three acts: Act One: The Awakening—learning about climate change; Act 2: Facing the Dragons—coping and overcoming barriers; and Act Three: A New Beginning—The Emergence of Ecological Consciousness. The model’s three-act structure mirrors the emotional, cognitive, and social shifts necessary for sustained engagement. Crucially, it underscores that climate change engagement is not a linear or solitary journey, but one shaped by community, culture, and collective meaning-making.

By reframing the “hero” as a metaphor for motivated, emotionally engaged contributors to climate resilience, we aim to inspire young people—and those who support them—to see themselves not as saviours, but as participants in a broader movement rooted in empathy, transformation, and shared responsibility.

4.1.1. Act One: The Awakening—Learning About Climate Change

Personal stories of ‘awakening’ abound in the climate change academic and advocacy spaces. These are the stories colleagues share among themselves of when they first ‘woke up’ to the reality of climate change and how such realization changed the course of their careers. For younger generations who were born when climate change was already acknowledged and its impacts felt worldwide, learning about this phenomenon through a singular event may be a less common experience.

Act One highlights multiple pathways through which young people can become aware of the ecological crisis, understanding that these pathways may very well overlap with one another. To contextualize Act One, it is also important to remember that our model is designed to specifically address the transformational journeys that young people who care about the planet undergo as they navigate the climate crisis, and that a fundamental prerequisite for young people to care about the planet is a connection to nature. This is why we placed nature connectedness at the very beginning of the model.

To keep with the hero’s journey’s metaphor, Act One begins when young people are living their familiar lives, characterized, among other things, by a deep connection with nature. Somewhere in their life story, they learn that the natural world they love so much is threatened by climate change, and this causes them to worry and being concerned about the future. How they learn about climate change and what they do to cope with the realization that the world, as they know it, is about to change, will determine what will come next in their journey.

One significant avenue for becoming aware of climate change is education, where young people learn about the impacts of this global phenomenon on ecosystems, people, and places. Climate change education not only increases awareness and knowledge of climate change but also elicits a wide range of emotional responses, some of which might be positive, while many more will be challenging (Grund & Brock, 2019; Keller et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2022). At the same time, in today’s digital age, media is a powerful tool for raising awareness about climate change. However, unlike education which should provide a balanced perspective on this issue, the media often emphasizes the adverse impacts of climate change and environmental degradation instead of the actions individuals and communities can do to counteract these effects (Schäfer & Schlichting, 2014; O’Neill et al., 2013; Hart & Feldman, 2014). This one-sided focus on impacts devoid of solution-oriented messaging has been shown to exacerbate feelings of anxiety in young people (Maran & Begotti, 2021; Marlon et al., 2019; Brulle et al., 2012), as the overwhelming nature of the crisis is highlighted without presenting actionable solutions.

In our study, we showed that young people rely heavily on the media for climate change information. Given that social media is relatively new, and today’s youth are among the first generations to use these platforms, it is unsurprising that they are becoming aware of climate change more swiftly than previous generations. Furthermore, the rise of popular video-based social media platforms, such as TikTok, may further accelerate this awareness.

Since its launch in 2016 and its surge in popularity in 2020, TikTok has allowed young people to witness firsthand video evidence of climate change impacts. Unlike other social media sites such as Instagram and Facebook, TikTok does not impose news-sharing restrictions, enabling young users to access content from around the world without limitations to their local news. For instance, during Hurricane Helene, a significant tropical cyclone that affected the southeastern United States in late September 2024, TikTok was flooded with real-time videos from those affected by the storm. While the storm was still ongoing, the hashtag #HurricaneHelene accumulated over 100,000 videos. Given TikTok’s status as one of the most widely used platforms among young people and its vast reach and content diversity, it is reasonable to conclude that such platforms contribute significantly to a more rapid awareness of the climate change threat among today’s youth compared to previous generations.

In the end, to keep the already complex pathway model manageable, we did not enter social media exposure in our main analysis, but we encourage researchers to further investigate media portrayal of climate change as a precursor to climate worry and eco-anxiety, given its potential importance.

Another way in which young people today may learn about climate change is by directly experiencing a climate-related event. Such firsthand experiences not only can lead to heightened awareness but can also be emotionally challenging. Furthermore, experiencing an extreme weather event could even potentially lead to post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and fear about future climate impacts (Berry et al., 2010; Cunsolo & Ellis, 2018; Ogunbode et al., 2021).

Additionally, theoretically, our model also recognizes the possibility that non-climate related events in a person’s life, the broader socio-political context, as well as developmental and relational dimensions, can significantly influence a young person’s awareness and emotional responses to climate change. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a young person might prioritize concerns about the global health crisis over climate change; in a country where conflict is present young people may be preoccupied with thoughts and concerns not non-related to climate change; and a young person may filter knowledge and information about climate change based on their personal and socio-cultural identities, evolving capacities, goals and aspirations.

We do recognize that complex contextual factors associated with The Awakening are largely unexplored and not accounting for them is a significant limitation of our study and the broader field of research. In fact, there is tremendous potential for critical and interdisciplinary approaches to expand our understanding of what happens at the very beginning of the journey, not only inside of the person, from a purely psychological perspective, but in the cultural, socio-political and relational theatres in which such experiences unfold. Similarly, very little is known about when the ‘awakening’ happens developmentally, because currently we have limited insights into how climate change fits in the broader ecology of a young person’s life. We believe there is an opportunity for researchers in this field to expand our research horizons by moving beyond viewing young people outside of their developmental journeys, not seeing them as relational beings, or entities detached from the cultural and socio-political contexts in which they are evolving.

4.1.2. Act Two: Facing the Dragons—Overcoming Barriers

Alerted to the dangers of climate change and motivated by their worry about the future, young people are pushed out of the Awakening state, and into a period characterized by complex emotions. This transitional phase is filled with challenges and barriers that young people must overcome to preserve their mental health and to enable their passage into the final phase of the journey, the emergence of ecological consciousness.

We call this transition ‘Facing the Dragons’, in part to keep with the metaphor of the hero’s journey (facing one’s fear and ‘slaying the dragons’ is a necessary step towards transformation and, eventually, success), but more importantly as a reference to Gifford’s Dragons of Inaction (Gifford, 2011). Like us, he resorted to a metaphor to categorize a wide range of psychological barriers individuals face that impede them from engaging with climate action. And while many of the barriers he unpacks are individual (e.g., biases and ‘errors’ we make due to the ancient nature of our brain), others are social in nature (e.g., social norms) and grounded in cultural identities and worldviews (e.g., beliefs and attitudes). In other words, the barriers young people will face in making sense of and coping with climate change are made of a complex entangling of psychological, contextual, systemic, and relational factors. This paints a rather complicated picture for scholars to understand.

At the theoretical level, we recognize that it is not possible to look at young people’s mental health responses to climate change outside of the broader socio-political, cultural, and developmental contexts in which they live. On a practical level, however, it is extremely challenging to conduct research that accurately accounts for all these influences at once. Therefore, researchers must choose what to exclude from their studies, and this inevitably leads to partial insights into this complex phenomenon.

Our study is no exception. We chose to focus on psychological dimensions at the expense of broader contextual factors, because we wanted to examine the combined effect of different types of coping styles on the mental health of young people who worry about climate change. Thus, we were able to show that to maintain good mental health, young people must strive to balance climate action with a sense of meaning and purpose, something a strong nature connection can provide, and that climate action alone puts their mental health at risk.

But let us revisit the findings that brought us to this conclusion. Earlier we showed that a strong connection with the natural world is a significant contributor to climate worry. At the same time, deepening a connection with the natural world may also motivate young people to become involved with climate solutions, because they want to protect something they love and see being threatened. This is important to remember in the context of Act Two, which centres around young people’s capacity for coping and overcoming barriers to action.

Our study suggests that for a young person to be able to cope with the emotions and stressors associated with their climate worry, they must go back to the root of that worry and cultivate constructive hope, a hope that acknowledges challenges while focusing on meaningful action to address them (Ojala, 2017). In other words, nature connection is both the ignition of worry and the source of meaning and purpose that sustains a young person’s motivation to keep doing their part.

While our model positions nature connectedness as a starting point for climate awareness and worry, it is important to consider whether a certain “depth” of connection is necessary to inspire meaning-focused coping strategies. Although the literature has not definitively established a specific threshold, emerging evidence suggests that deeper, more affective forms of nature connection—those involving awe, empathy, and identity-level bonds—are more likely to be associated with intrinsic motivation and meaning-making (Zylstra et al., 2014; Tam, 2013). In this view, superficial exposure to nature may not be sufficient to sustain the emotional resilience needed for constructive coping. Rather, it may be the quality and emotional richness of nature connectedness that underpins a young person’s capacity to derive meaning and take purposeful action amidst ecological distress.

To substantiate this perspective, we showed how different coping styles are associated with different mental health outcomes. Furthermore, our results showed that, consistent with what Pihkala (2022) also had envisioned in his model, young people who succeed in diversifying their coping strategies are more likely to reach the final stage, Act Three: Emergence of Ecological Consciousness.

But let us take a closer look at what characterizes the transitional phase of Act Two. In Act One, we showed that people who feel more connected to nature are more likely to worry about the future because of climate change and because of this worry, they may also experience greater depression and anxiety than their counterparts. The onset of mental health challenges marks their transition into Act Two, a stage characterized by active efforts to regulate intense emotional responses through strategies that foster emotional awareness, self-validation, and constructive engagement (Börner, 2023; Verlie, 2021). However, some may swiftly move to action attempting to ease their anxieties, while others may dwell in their state of inaction, not knowing what to do.

How they respond to their emotional discomfort at this point in their journey is determined by a complex interplay of personal (psychological, developmental), socio-cultural, systemic, and contextual factors. Act Two is characterized by multiple barriers working simultaneously to impede a young person’s ability to navigate these difficult times and focuses on the role that climate emotions, climate action, and nature connectedness play in this complex picture. While we acknowledge that not accounting for broader and contextual factors may potentially lead to oversimplified conceptualizations, it is nonetheless a valid endeavour to attempt to better understand how engaging with these key dimensions can lessen or enhance young people’s risk to encounter mental health struggles (Hogg et al., 2021; Ojala et al., 2021; Bouman et al., 2020; Cunsolo & Ellis, 2018).

It is important to point out that feeling worried about climate change and experiencing complex emotional states is a proportional response to the magnitude of the threat posed by climate change. However, there are two perspectives about this very point: one that stresses the normative nature of climate worry and anxiety; the other that wants to frame these in terms of psychopathology.

For example, revisiting the term “eco-anxiety”, which has emerged in climate psychology discourse as a catch-all for the psychological symptoms associated with the climate crisis, we are of the school of thought that does not consider eco-anxiety as a psychiatric condition. This is because severe mental distress or clinical symptoms of eco-anxiety are rarely observed in young people (Berry & Peel, 2015; Clayton & Karazsia, 2020; Ogunbode et al., 2021; Wullenkord et al., 2021). Instead, labelling young people’s well-founded concerns about climate change as “eco-anxiety” risks pathologizing a natural and appropriate response to a significant stressor.

This is akin to how we wouldn’t consider anxiety about an upcoming job interview as a mental health issue because we tend to view such anxiety as a valid emotional response to a challenging situation. The problem arises, not from the anxiety itself, but from the lack of effective coping strategies to manage it. If a person does not know how to address the anticipatory emotions elicited by the prospect of a job interview, their mental health may be negatively impacted. However, these impacts are due to inadequate coping strategies, not the anxiety itself, as this anxiety is generally expected given the circumstances.

Viewing young people’s climate-related experiences and emotions solely through the lens of psychopathology oversimplifies the issue. It frames the problem as being internal to the young person rather than acknowledging the external realities of the climate crisis. Therefore, creating scales to measure the dysfunctional aspects of eco-anxiety, such as the Climate Anxiety Scale (Clayton & Karazsia, 2020), without also accounting for contextual factors not only may be of limited value, but it could also be misleading.

But dealing with anxiety associated with typical life circumstances is not the same as having to cope with the prospect of an existential threat. For example, in the case of a job interview, an effective way to alleviate this type of anxiety is through problem-focused coping, such as preparing by practicing with a friend. In fact, for micro-level problems like this, problem-focused coping has been positively related to well-being (Clarke, 2006; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) as it helps remove the stressor from one’s environment. However, climate change is a polycrisis, not a micro-level problem, and so removing the cause of climate change is not possible for any given person alone. Research has suggested that youth who primarily use problem-focused strategies to cope with climate change tend to experience greater anxiety (see Ojala, 2012a, 2012b). Therefore, to alleviate climate related anxieties, young people must draw from their inner resources and rely on external support systems to properly navigate this potentially harmful emotional state. Furthermore, without proper emotional and meaningful engagement, constant action-oriented strategies can become distressing and overwhelming. Instead, meaning-focused coping emerged in our study as the crucial factor in protecting mental health for young people who feel deeply connected to nature and are worried about climate change. In fact, we found that a strong connection to nature and heightened climate worry are associated with improved mental health among those participants who report using meaning-focused strategies: as a young person’s connection to nature deepens, their worries about climate change also intensify. Initially, this heightened worry may lead to increased feelings of anxiety and depression; however, it also encourages engagement in meaning-focused coping strategies. These strategies, in turn, can reduce the likelihood of experiencing the mental health struggles associated with climate worry.

In other words, by finding meaning in their actions and understanding their role in addressing the climate crisis, young people can sustain their commitment to climate change while maintaining their mental health. It is at this point that they are ready to enter Act Three where they experience the emergence of a new consciousness which will guide them through the ups and downs of the climate crisis, deepening their relationship with the self, other and the natural world.

4.1.3. Act Three: A New Beginning—The Emergence of Ecological Consciousness

Like other studies, ours shows that climate worry can serve as a powerful motivator for action and it can be a constructive response to climate change (Bouman et al., 2020; Kurth & Pihkala, 2022; Verplanken et al., 2020). This is unsurprising, given that, viewed from an evolutionary perspective, anxiety is known to have played a crucial role in our survival by alerting us to threats and prompting action. This inherent ability to experience anxiety is what drives us to address significant issues, including climate change. Without being worried or anxious about climate change, we might lack the motivation necessary to engage with and tackle this pressing problem.

In Act Three, young people engage with behaviours that are driven by meaning and purpose, rather than being reactive and fuelled by urgency. Their actions are more thoughtful and coherent with their own identities. They are not just individual actions, but they are also part of collective efforts. These meaningful, collective climate actions then have a protective effect on young people’s mental health because they reinforce their personal commitment and contribute more broadly to the fulfilment of their social and developmental needs. Young people who enter Act Three have successfully overcome their personal barriers to engagement with climate action; they have grown into individuals who have clarity about their purpose and possess strong inner qualities; they feel interconnected with the world around them; they have established meaningful relationships with like-minded individuals; and feel that they belong to something bigger than themselves. Finally, they are committed to saving the natural world from destruction and dedicate time and attention to their relationship with nature. Through the profound transformation that young people undergo as they inch closer to Act Three, which is conceptualized as a new beginning rather than the end of the journey, they have also changed the way they perceive the world. Now, they understand that seeing human beings at the top of the hierarchy is problematic. They are beginning to internalize the idea of interconnectedness of all things. In other words, they have moved past anthropocentrism and have acquired a new ecological consciousness.

This new ecological consciousness, which embodies cognitive, ethical, emotional, and spiritual shifts, is rooted in reverence, kinship, and sacredness of nature. It deepens when drawing on Indigenous and eco-spiritual worldviews (Ives et al., 2018); while mindfulness practices can also provide a bridge between secular and spiritual practices, fostering non-dualistic awareness of human-nature interdependence (Wamsler & Brink, 2018). Finally, this new ecological consciousness centres on ecocentrism which aligns with spiritual-ecological principles of intrinsic value and cosmic interconnectedness (Kortenkamp & Moore, 2001). This new ecological consciousness, therefore, will become a driver for young people’s commitment to be part of climate solutions which, now they understand, not only requires policy and behavioural change, but also a transformative reimagining of humanity’s place within the web of life.

Equipped with their new ecological consciousness, young people are now ready to contribute to the climate crisis, meaningfully and sustainably. The question that remains, however, is whether the adults they will encounter will be ready to work with these eco-conscious generations and how systemic barriers will be eliminated to allow them to meaningfully participate in climate solutions and actualize their full potential.

In conclusion, the Developing Ecological Consciousness Model is proposed as a framework to conceptualize the multifaceted process young people undergo as they learn to live in a world transformed by climate change. From Act One, when they become aware of climate change; to Act Two, when they struggle as they find their way; and finally Act Three, where they emerge transformed, this model provides a comprehensive view of the emotional, behavioural, and spiritual journey young people who worry about climate change will likely undertake.

While limited in its integration of contextual and systemic factors that also play a critical role in this journey, we offer valuable evidence-informed insights into how young people navigate their responses to climate change. In the following section, we will further discuss the limitations of our work and explore areas for future research.

4.2. Limitations of the Current Study

Understanding the limitations of our study allows readers to draw their own conclusions about and interpretations of our findings. Here, we list the limitations we think are most relevant, hoping to inspire researchers to expand our work and continue building solid empirical and theoretical foundations in this emerging field of research.

First, the participants in both samples were first and second-year undergraduate students at one Canadian university, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to young people from other Canadian and global contexts. Future research on climate worry and coping should include diverse samples from other regions of Canada, such as Northern Indigenous communities, where youth are particularly exposed to climate impacts and more vulnerable to eco-anxiety (Cunsolo et al., 2020; Galway & Beery, 2022). Additionally, studies should use samples from countries at higher risk of experiencing the direct impacts of climate change and an increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. This approach is essential because individuals in these regions are more likely to face climate-related challenges directly, which can profoundly affect their emotional responses and coping strategies, offering insights that go beyond those from indirect experiences.