Abstract

High-quality health education in schools plays a critical role in the formation of young people by developing the attitudes, beliefs, and skills needed to adopt and maintain healthy behaviours throughout their lives. Curriculum reform processes ensure that health education is adequately preparing adolescents for the world today and in the future. However, there is little consideration given to the teachers implementing these curriculum reforms, and their ability to integrate changes as they shape their learning and teaching. In this paper, we discuss the worldviews and beliefs of the teachers delivering health education in Western Australia. We present findings from a doctoral grounded theory study within secondary schools to explain the process teachers use as they approach curriculum, particularly after a reform. We investigate how teachers struggle to decide how to present themselves and the new curriculum content in class. Our findings evidence that teachers have determined gender and sexuality content to be controversial, uncomfortable, difficult to teach but also a favourite to teach. Teachers have expressed uncertainty as to what to say in class and have called for further guidance to teach these important life lessons. Curriculums need to constantly change to keep pace with a changing world, so how do we do this in a way that supports teachers and ultimately produces the best education for young people?

1. Introduction

For decades, children and adolescents in Western Australia have engaged in health education classes. The content of these classes evolves with curriculum reforms, as has occurred in Western Australia over the past 40 years. Health education is widely recognised for addressing current health issues and equipping students to live healthy lives. In Western Australia, health education is taught as one stream of the Health and Physical Education Learning Area and mostly taught by Health and Physical Education teachers. This paper examines the experiences of teachers working with young Western Australians to implement the latest health education curriculum, the Western Australian adaptation of the Australian Curriculum: Health and Physical Education (AC: HPE). This curriculum was developed by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) in 2016 and resulted in the School Curriculum and Standards Authority (SCSA) in Western Australia (WA) then reforming the WA curriculum.

Curriculum reform is seen as a necessary step to help schools adapt to our rapidly evolving world (Giannikas, 2022). Although changing the curriculum is intended to drive school-level improvements, this is not always straightforward. Such reforms often involve introducing new content that teachers must interpret and understand. Between 2015 and 2017, a new Australian Curriculum syllabus for Health and Physical Education was developed, with additional reforms taking place from 2021 to 2022. During the period from 2017 to 2022, Western Australian teachers were tasked with interpreting, understanding, and implementing this updated curriculum content.

For teachers, implementing a curriculum is an ongoing process and its importance is self-evident in how teachers’ decisions can directly and drastically impact student outcomes. A key student outcome from well-delivered comprehensive sexuality education is the positive health and wellbeing impacts supporting young people to flourish as they understand, experience, and express their own unique sexuality. Effective health education curriculum implementation can have a lasting impact on the rest of a student’s life (World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2012).

Although curriculum implementation may seem like a straightforward process to simply follow the prescribed curriculum, it actually involves teachers interpreting new curriculum ideas and instructions, while taking into consideration their own beliefs, attitudes, and values, together with those of their school, students, and parents. They must then develop teaching and learning programs that are both suitable and contextually relevant.

Reform practices such as adopting new terminology, and new or revised content, will likely necessitate re-interpretation and implementation. During this process, there is interaction between the curriculum and a teacher’s personal beliefs and their broader worldviews, thus revealing the hidden curriculum (Shelley & McCuaig, 2018). In this way, the distinction between the formal written curriculum and the realities of what occurs in schools and classrooms is revealed.

Following a curriculum reform, teachers are asked to approach the new or revised curriculum documents (Luttenberg et al., 2013) and attempt to make sense of them. They consider how to accommodate the new ideas within their own perspective. This sense-making of curriculum has been described by Lambert (2018, p. 7) as, “an activity influenced internally by personal and professional values, experiences and motivations”. A teacher in this study described it as, “it’s just a matter of applying what you know into an educational context”.

When interpreting the curriculum document, teachers make decisions about whether to adopt or adapt the curriculum (Ross, 2017). Adaptation may involve contextualising the curriculum, interpreting it in a certain way or omitting certain elements.

Teachers often find difficulty in separating parts of themselves from their teaching (Glanzer & Talbert, 2005) with many teachers desiring to align course content with their beliefs and broader worldview. In Western Australia, especially in government schools, many teachers believe that they should present a neutral stance and refrain from sharing their personal views in class (Lyle, 2013). In contrast to this purported neutrality is authenticity in the classroom, which allows educators to express their true selves and encourages students to do the same (Cohen, 2018).

Teaching health education can be difficult, challenging, and occasionally stressful for teachers (Cliff et al., 2009; Collier & Dowson, 2008; Gibson, 2009; McCuaig & Hay, 2013), particularly during periods of curriculum reform (Lambert, 2018; Matthews, 2014; Zimmerman, 2006). Mayo (2022) describe issues surrounding sexuality and gender identity as difficult and complex. Due to this difficulty, many teachers have reported a need for support and guidance especially when teaching sexuality and gender topics, as they perceived them to be sensitive or controversial.

Donnelly and Wiltshire (2014, p. 204), in their review of the reformed Australian Curriculum, stated that “the most controversial area by far is sexuality education”. This view was supported by Van Wichelen et al. (2023) who also reported on the controversial nature of sexuality and gender education. They reported that teaching sexuality was “a very challenging area for teachers, with many teachers having little or no undergraduate training in sexuality and being unsure of pedagogical approaches” (Van Wichelen et al., 2023, p. 589). According to Donnelly and Wiltshire’s research, the issue is not simply the case that teachers choose their teaching methods; rather, they struggle deciding which methods to choose and find this process highly challenging. The reformed Australian Curriculum provides little guidance for teachers as to how to go about teaching this new content and no elaborations as to the meaning of the new terminology (Gerber & Lindner, 2022).

Adding to the difficulty of teaching health education are any changes to the ideology behind the new methods of teaching. Macdonald, the lead writer of the AC: HPE (Macdonald, 2014, p. 245), announced that the new direction of the AC: HPE would serve to refresh teaching practices by helping teachers adopt a “critical public health orientation”. While the Australian Curriculum still included biophysical and behavioural knowledge, as was the primary focus in previous curricula in the health education field in Australia (Macdonald, 2014), it now valued sociocultural knowledge and introduced a strengths-based, critical health literacy and critical inquiry approach.

This reform introduced new content to the Australian Health Education curriculum such as gender and sexuality content. This new content in conjunction with the reformed ideology of a sociocultural pedagogies was novel to Western Australian teachers.

Previous curricula in WA did not include constructed sociocultural knowledge nor a critical inquiry approach. Historically, teaching methods in Australian health education had favoured other philosophies such as risk-based teaching (including ‘scare tactics’), harm minimisation and a focus on knowledge and understanding, mainly for teacher-led didactic lessons (Barwood et al., 2016; Lambert, 2018; McCuaig & Hay, 2013). Lambert (2018) suggested that the new AC: HPE is conceptually challenging, making teachers apprehensive.

In addition to adjusting to curriculum reform, health education teachers are now expected to develop the moral character of their students, as schools increasingly focus on moral education. As Glanzer and Ream (2008, p. 4) aptly describe teachers “seek to educate students about the good, form their love for the good, and encourage them to do the good”—presumably by offering cognitive knowledge and guiding students to envision a particular vision of the good life (Glanzer & Ream, 2008; Sire, 2015).

The Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (often referred to as the Melbourne Declaration) set the direction for Australian schooling for ten years in Australia, beginning in 2008 (Barr et al., 2008). Reform to the Western Australian and Australian Curriculums were, in part, a response to this Melbourne Declaration. It stated that the vision of ‘the good life’ is described as students’ sense of optimism about the future and the development of personal values and respect for others (Barr et al., 2008). It seems there are three versions of ‘the good life’, those being the teachers’ vision of ‘the good life’; the curriculum’s vision (underpinned by the Melbourne Declaration); and the school’s vision. A central theme explored in the study was how a teacher guided students toward morally acceptable and healthy behaviour, especially in challenging areas such as sexuality and gender education.

These ‘visions’ are underpinned by a person’s beliefs and practices, reflecting their worldview (Tsybulsky & Levin, 2019). Since people are often not fully aware of all aspects of their worldview, it can be a challenging concept to analyse (Rousseau & Billingham, 2018). Therefore, exploring and discussing beliefs and behaviours was a crucial aspect of this study.

Although one role of the health teacher is to help students explore their ‘attitudes and values’ (SCSA, 2016), Lynch (2014) noted that this task can be stressful for teachers. Hill (2005) also reported it was difficult for teachers to help students explore their attitudes and values without revealing their own personal belief systems and their worldview.

Shelley and McCuaig (2018, p. 4), prominent researchers dedicated to improving young people’s health through quality school-based education, reported that “pervasive health messages bombard all members of society”. It follows that because health teachers are a part of society, they do not escape this influence. Moreover, Shelley and McCuaig (2018, p. 4) reported that, “most people have a perspective on what health means and what should be done about it, with a greater potential for personal attitudes, values and beliefs to intersect with curriculum enactment”. Given that a teacher’s personal view on health can shape what is taught and how their beliefs influence curriculum delivery, it is crucial to understand teachers’ beliefs and how these fit within their broader worldviews.

This paper will address the complexities and difficulties of teaching health education; discuss the existence of sensitive and controversial issues in health curricula; and then explore the personal perspective of teachers and the ensuing interaction with teaching practices. The link between teachers’ personal perspectives and the decisions they make when choosing teaching methods, content, and deciding how to communicate controversial issues in their classes will be explored as these constructs ultimately have an impact on the learning experience of students in health education classrooms.

The aim of this study was to explore the broader personal beliefs of the teachers delivering the PSCH as part of the HPE Learning Area in Western Australia, based on the premise that their beliefs have an impact on the way the course is delivered. The research question was ‘What are secondary school health teachers’ perceptions and experiences of mandated curriculum reform, with particular reference to the personal, social and community health strand of the Western Australian health and physical education curriculum?’ This study examined the stance of teachers regarding neutrality and authenticity as they taught health education that includes controversial and sensitive topics such as contraception (Barbagallo & Boon, 2012; Eisenberg et al., 2013; Fincham, 2007), homosexuality (Barbagallo & Boon, 2012; Fincham, 2007; Smith et al., 2011), and relationships education (Fincham, 2007).

2. Materials and Methods

This current research aimed to develop an understanding of the impact of teachers’ personal beliefs and worldview on the delivery of health education curriculum, including their pedagogical choices, and provide a detailed description of the experiences of teachers as they deliver sensitive content and teach a challenging curriculum. It involved a three-phase qualitative methodology, drawing from a constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz, 2015) in order to induct a theory from the data, collected from a series semi-structured interviews that took place between May and November 2020.

Research participants were sought using a criterion sampling technique (Moser & Korstjens, 2018), in which the predefined criteria were: subjects are currently being employed as a teacher in a secondary school in Western Australia and currently delivering the PSCH to students in years 7–10 (or any subset of that group). Participants were drawn from each of the three education providers in Western Australia: State Government (777 schools), Catholic Education (159 schools) and the Independent schools sector (132 schools). Arising from these criteria is the expectation that the subjects were engaged in implementing the new Personal, Social and Community Health (PSCH) curriculum, including needing to interpret the new curriculum as text and apply this meaning to their teaching practices.

An email invitation was sent once to known teacher email groups (with subscribers ranging from 500 to 2400 members) and was also advertised in a range of teacher interaction sites. Respondents to the advertised study were screened via phone call or email to determine that they met the criteria of currently teaching PSCH in a Western Australian secondary school. Two respondents were excluded due to not currently teaching PSCH in a secondary school. Each participant’s informed consent was then obtained prior to interviews commencing, and participant data were subsequently anonymised to avoid identification.

A total of 23 teachers took part in the study; however, exigencies occurred as the research unfolded, resulting in not all participants being able to continue throughout the whole study. In phase 1, the 23 participants were drawn from a wide variety of schools, Western Australian regions, socioeconomic status groups and sectors, comprising 9 male teachers and 14 female teachers, 22 of whom identified as heterosexual people and 1 who identified as homosexual; of the 23, 22 were HPE-trained teachers and 1 teacher was a non-HPE teacher who had been allocated a health education class that year. In phase 2, the total was reduced to 22 participants because 1 participant gave birth to her baby at the beginning of the phase 2 interview process. The participant number reduced to 19 in phase 3 due to 1 participant becoming ill and 2 participants failing to respond to invitations to participate in the phase 3 interviews.

Participation was voluntary, and teachers were asked initially to participate in an information screening process, followed by completing a consent form. The predefined criteria that participants were screened for included: subjects currently being employed as a teacher in a secondary school in Western Australia and currently delivering the PSCH to students in years 7–10 (or any subset of that group).

According to Charmaz (2012), interviews allow for participants to define what they mean and explain their point of view, and as such she recommended the use of multiple sequential interviews in grounded theory studies as they allow the researcher to revisit discussions and check the interpretations about ‘what is happening’. The data collection itself consisted of three semi-structured interviews that lasted between 26 and 87 min.

Coding the data involved initial open coding, followed by continual comparative analysis, memo writing, focused coding, and visual representations. This analysis has been used to form categories and, ultimately, theory development.

Prior to starting this research, ethical approval was secured from the Higher Education Ethics Committee of Alphacrucis University College, the university of which the researcher was enrolled in the Doctoral program.

3. Results

This section will report on a selection of key findings of this study, specifically regarding the teaching of gender and sexuality. These results are drawn from the interview transcripts of 23 Western Australian teachers. Please refer to the Supplementary Material for the full participant list detailing age group, role and school type. Results below have been categorised into two key groupings: (1) Relationships and Sexual Education and (2) Health Education Teaching Perspectives.

3.1. Relationships and Sexual Education

Teachers considered relationships and sexuality education as being of utmost importance, dedicating considerable effort into ensuring that students learnt the concepts of safe, respectful relationships. When discussing their approach to teaching relationships and sexuality content they mentioned: pornography, consent, abusive relationships, sexually transmitted infections, screening, contraception, use of alcohol and other drugs and the impact on relationships, decision-making, beliefs and values, abstinence, communication skills, online relationships, love, abortion, and rights and responsibilities.

However, due to the often confronting or controversial nature of the sexuality content, some teachers described it as extremely difficult to teach. This was seen in comments such as, “I find it incredibly uncomfortable”, and “I just completed a unit on sexual relationships, but I mean, I’m awkward at the worst of times”.

The list of controversial topics generated from the phase 1 interview responses mainly consisted of topics from the relationships and sexuality focus area, including sexuality, gender, diversity, homosexuality, sexual health, abortion, and sexual identity. In phase 2 interviews, teachers were asked to describe a lesson they had recently taught on a controversial or difficult topic, with 18 of the 22 participants selecting a lesson from the relationships and sexuality focus area. These 18 lessons included lessons on sexual identity, pornography and sexting, sexual assault and consent, contraception, respectful relationships, gender, homophobia, sexual risk taking, pornography, consent and abuse of rights, power and control, homosexuality, sexual health, gender and identity diversity, responsibilities in relationships (including consent), syphilis, and contraception versus abstinence. These topics had all been taught within a few weeks leading up to the phase 2 interview.

Interestingly, the word ‘abstinence’ is not actually mentioned in the WA health education curriculum; however, it was mentioned by nearly all the teachers in the study who said something very similar to this teacher:

My mention of abstinence is that it is a form of contraception and that it’s the only one that’s 100%, you know, safe and 100% proven that nothing, you know, you’re not going to get an STI or pregnant or anything if you’re not having sex.

Health teachers were mindful of the public discourses surrounding controversial issues in their curriculum. The teachers in this study were particularly concerned about the spread of misinformation and as health teachers they recognised the need to “put it [health matters] in a way that students can understand”, as one respondent noted, while correcting misconceptions, and empowering students to decide for themselves what is true or right.

Health teachers are seemingly cautious about contributing to misconceptions and misinformation already existing in the public domain. They choose their language carefully, so as not to offend, and to ensure the message is clear and easily understood. One teacher illustrated this concern when discussing sensitive topics: “They’re exhausting those lessons, because you’re thinking all the time, and making sure that what you say is going to be, there’s no other interpretation to what you say that could lead a kid down the wrong path”. While it is accepted by health teachers that they need to address misconceptions and manage perceptions in their own contexts, they may not always be fully aware of current public discourse. Many teachers feel unprepared to empower students and address the controversial issues, for example, “You kind of second guess yourself, because I feel like Australian culture, I don’t really know what’s appropriate and what’s not because we always go under the banner of we don’t know whether it’s being offensive or not”. This uncertainty could stem from the evolving nature of Australian attitudes on issues like transgender and LGBTQI topics, or from teachers’ limited engagement with and awareness of current public discussions and how perceptions are formed.

Teachers in this study were asked to identify content from the WA health education curriculum that they found difficult, uncomfortable, controversial or their favourite to teach. This questioning opened up the discussion and allowed insight into the personal views of the teachers regarding the curriculum, helping the researcher to notice the interrelationship between the teachers’ worldviews, personal beliefs and curriculum delivery.

Teachers identified many topics as their favourite to teach including sexual education; for example, “I like teaching puberty and I like teaching sexual health because it makes them so ahh [laughs], and I like teaching like nutrition and all of that kind of stuff as well”.

Teachers also referred to some sexual health content as uncomfortable to teach such as, “Give it sex ed, give it talking about gender identity. Same sex relationships, whatever it be, I’ve always felt uncomfortable, so I avoided it”.

Teachers pointed out how interconnected these topics all were for example, “When you’re talking about, you know, developing your sexual identity and going through puberty, and then it all starts the big gender conversation, and it gets pretty controversial and hard to answer sometimes”.

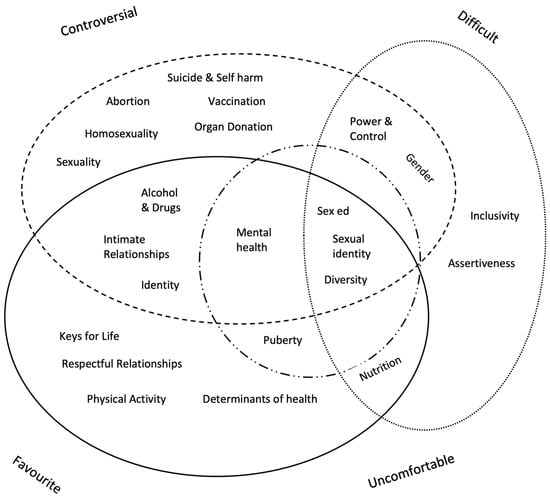

The grounded theory approach emphasises focused coding (Charmaz, 2014) to build on initial coding and to begin to transform basic data into more abstract concepts, thereby allowing theory to emerge. Focused coding in this study organised the data in such a manner that allowed for the emerging of categories. This categorisation of health education topics was graphically displayed in a Venn diagram (see Figure 1) to reveal overlap between the categories and to allow interactions to emerge.

Figure 1.

Topics categorised according to favourite, uncomfortable, difficult, and controversial (Lockhart, 2022).

Grounded theorists hold that creating visual representations of the emerging theories is an intrinsic and essential step in theory building (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The use of diagrams during data analysis, as used in this study, helped in showing detailed or causal explanations.

Of note are the three topics in the centre of the Venn diagram; they are all from the relationships and sexuality focus area, that being Sex Ed, Sexual identity, and Diversity. These topics are considered uncomfortable, difficult, and controversial but also a favourite to teach. Gender is considered controversial and difficult but was not categorised as uncomfortable or a favourite to teach. Interestingly, this research highlights that content that is viewed as difficult, uncomfortable or controversial is not always avoided or taught poorly; it is often a favourite topic to teach and teachers enjoy the discussions and learning that happens in these classrooms.

The way that the relationships and sexuality content in the WA health education curriculum was written caused frustration for 13 of the 23 teachers in this study because they believed content covering safe sex practices had been reduced in this new curriculum or omitted altogether. This omission by ACARA in the Australian Curriculum had a flow-on effect into the WA health education curriculum and it was suggested by some participants that this omission was possibly to provide space for the addition of gender diversity and sexual diversity type content.

Teachers referred to the health curriculum as “wishy washy”, increasing the difficulty to correctly interpret and deliver the content. Additionally, students themselves posed questions or took the discussion in certain directions, which could then be difficult for teachers to navigate, such as this teacher’s experience:

Yeah, so sometimes I get, some curveball questions, in regard to same-sex marriage in, you know, ‘Are we born gay?’ and, you know, abortion and I do get these types of questions and, and that’s where I need to tread really carefully.

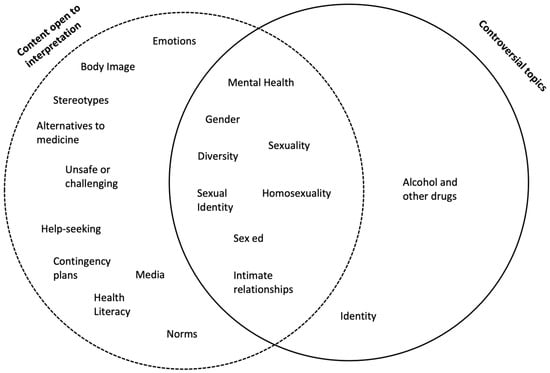

Using the constant comparison technique, data were analysed both within and across categories. It was found that content deemed open to interpretation was most likely to be understood differently by various teachers. Additionally, because controversial topics inherently provoke public disagreement, they are often interpreted in diverse ways depending on individuals’ worldviews, leading people to favour one perspective over another. These comparison data were presented in a Venn diagram (Figure 2), depicting commonality between content believed to be open to interpretation and topics considered controversial.

Figure 2.

Comparison of controversial topics and curriculum content that is open for interpretation (Lockhart, 2022).

All the topics identified as controversial by teachers in this study, except alcohol and other drugs and identity, were also categorised as open for interpretation. The teachers’ worldview and personal beliefs are most likely to come into play when interpreting the curriculum content, and in particular, with regard to controversial topics.

The topics that were considered both controversial and open for interpretation were intimate relationships, sex ed, homosexuality, sexual identity, gender, diversity, sexuality, and mental health. This list includes sex ed, sexual identity, and diversity, the three topics identified by teachers as uncomfortable, difficult, controversial but also a favourite to teach. So, these topics are difficult, controversial and also highly open for interpretation, making teaching them particularly hard.

Teachers in this study expressed uncertainty about what to say in class regarding this content. For example, one stated, “I don’t want to interpret it wrong, and then the consequences of not recognising emotions of others, like if I was a new teacher having to write a program for this, that’s when I might be like, unsure”.

Teachers reported that it was a struggle to teach sexuality and the concern for students who decided they were non-binary. Teachers expressed nervousness about parent or community backlash derived from teaching about gender or transgender issues because these issues can have lifelong consequences for young people and they were concerned about the students’ mental health. One teacher stated:

You’ve got to be very, very careful because, you know, you don’t want to, I mean, you don’t want to do anything that’s going to damage the mental health for a start. But also, it’s a very unpopular opinion to say ‘Well, could you not just live as another, as the other gender or the gender you’re choosing to identify as, and then have permanent surgical procedures, like later when you, you know, when all the hormones have calmed down?’ That’s probably, yeah, at this point in time, that’s probably the most controversial thing that’s going on.

Some teachers believed transgender students may change their mind when they got older, and this had not been considered in current thinking about sexual identity. Another teacher said:

Non-binary yeah, and they’ve all decided they’re something. And um, I just, I just wonder how much of this is trending and that when they get older, do they um change their mind because a lot of them haven’t told their parents and it’s, um, yeah, I really struggled with that because it wasn’t around when I was a kid. I wonder how much of that has something to do with social media and yeah, a lack of resilience or the need for something that makes them stand out.

Teachers were mindful of the expectations from the school regarding gender diversity, where they needed to ensure that the feelings of transgender students were taken into consideration while maintaining confidentiality and the privacy of those students. A teacher spoke of how difficult this is:

I’ve got a couple of kids at school, who were going through the Gender Diversity Centre. So, you know, trying to teach, teach that and be and be cognisant of how they’re feeling and how you address them and all of that sort of stuff in class when a lot of their classmates don’t know what’s going on in their world is really quite, really difficult.

3.2. Health Education Teaching Perspectives

During discussions of teachers’ beliefs, six (6) of the twenty-three (23) teachers in the phase 1 interviews spoke about how they formed their beliefs, with five (5) of them citing life experiences as the main source of belief formation. As one stated, “I’ve developed my own perspective on this world, and it’s been generated, I guess, through life experiences”. In phase 2, teachers were asked more specifically how they formed their personal beliefs about the topics they teach, and formation sources such as life experience, research and reading, professional learning, and university study were most commonly suggested.

Five (5) teachers spoke of their beliefs and knowledge having “always been there”, of being “pre-disposed” to certain viewpoints and having an “interest” in being healthy from a young age. Their passion for healthy living began “before uni” and was closely related to their “values”.

Of the twenty-three (23) teachers interviewed in phase 1, thirteen (13) expressed a belief that decisions about what is right or wrong should be based on the healthy choice. A teacher put it like this, “So I feel that like, getting the kids thinking about their values, attitudes and then apply it. So, how’s this going to push on for the rest of your life? Is that the healthy thing? Can we change it?” It was reiterated by several teachers in this study that the healthy choice is the right choice such as, “Educate them on those things and how to stay healthy, stay safe, as much as anything”.

They emphasised that the healthy choice was central to the teaching of health education by saying:

When I go into the classroom, I’m, like, we’re learning about sexual health now in year 9 and I just think, like, I really want these girls because it’s a girls class to make, like, the best decisions they can for themselves and just like, um, yeah, make healthy decisions. So yeah, I guess with everything, I am, I’m trying to emphasise, like, what’s good decision making.

Regardless of the topic being taught, fifteen (15) of the twenty-two (22) teachers interviewed in phase 2 expressed the belief that they needed to teach students to be healthy or safe. This was seen in quotes such as, “Someone’s gotta tell the kids like, they need to know that, they need to know how to be safe”, “We are equipping the kids to make healthy decisions for the rest of their life” and:

It always has to come back to the point of why I teach this topic, which is you need to be able to stay safe and know how to avoid something, if it’s going to be unsafe for you, or the people around you.

The notion of what healthy and safe means for students was believed to be a personal decision, with five teachers indicating an acknowledgement of respect for diversity. Teachers were asked specifically in phase 3 what was meant by the terms ‘healthy’ and ‘safe’, in response to memos generated in phase 2 of the study. Ten (10) of the nineteen (19) teachers in this phase of the study referred to a holistic view of health and the dimensions of health when defining the term ‘healthy’. The dimensions of health include mental, physical, social, emotional, and spiritual health (Hjelm, 2010) and this was seen in in a teacher’s statement, “I would say that it’s about making choices that are good for your mind, body and spirit, and understanding why you’re making those choices”.

4. Discussion

While the curriculum is often considered neutral and is expected to be delivered uniformly, the grounded research being presented in this paper found that teachers differ greatly in their practices and interpretations. Teachers’ individual perspectives shape how they approach curriculum, often leaving teachers feeling unsure as to how to best prepare students for their everyday adult life. Rather than criticising this taken-for-granted view of curriculum, perhaps curriculum writers and educational leaders ought to address the diverse perspectives of educators, and the wider society, regarding controversial topics found in the health curriculum. Embracing authenticity and relevance in classroom interactions could help reimagine how students are best prepared for the modern world.

This embracing of authenticity was promoted by Rhodes (2019), an educational leader and researcher from the USA, who recommended teachers need to share their stories because they “have powerful, positive stories of determination and perseverance, stories that reflect who they are as people and as learners” (p. 2).

We are living in extraordinary times, raising questions about the education system’s ability to not only adapt and remain flexible but also to address the fundamental ontological issue of whether our education curriculum remains fit for its intended purpose. The Melbourne Declaration Goal 2 (Barr et al., 2008) positions students to become ‘active and informed citizens’ and, in reality, as evidenced here, teachers are feeling ill-equipped to prepare students for the development of healthy gender and sexual identities. Some researchers have attributed the lack of resources for health education teaching in Australia as a potential reason for teachers feeling ill-equipped, such as that of Waller et al. (2017) and Collier-Harris and Goldman (2017).

Three limitations were identified in this study: (i) The level of generalisability when discovering the emergent theory is considered limited given that the theory is grounded within a specific situational context, (ii) Bias could have been introduced given the interpretative nature of the methodology and the researcher’s close proximity to the data, and (iii) The empirical data were limited to only one region within Australia, that being Western Australia.

The personal beliefs, worldviews and perspectives of the health teachers have an impact on how they approach and interpret curriculums, especially when approaching content open for interpretation, controversial topics and content that is difficult and uncomfortable to teach.

Participants in this study regarded diversity and sexuality content to be highly controversial, open for interpretation, and challenging. They also noted that prevailing beliefs about this content are continuously evolving, which requires teachers to invest considerable thought and reflection in developing their teaching approach. This notion of content evolving was also found in New Zealand in a study by Fitzpatrick et al. (2022) who reported that gender and sexuality norms are shifting and now more diverse than ever. This places increased onus on the health teacher to constantly upskill and remain abreast of changing societal views in order to be prepared for class.

Some teachers experienced increased pressure during the interpretation phase, feeling that the curriculum appeared “wishy-washy”. Conversely, others embraced the challenge as an opportunity to personalise their teaching. This comes with a warning though that freedom brings with it a level of tension for the health teacher who, at times, would prefer clear directions as to what to teach. Teachers recalled the need to go back and revisit the curriculum text to ensure the teaching program aligned with the original text. A clearer curriculum text could likely minimise the need for such back-and-forth between interpretation and implementation.

Teachers experienced the most difficulty with sexuality, gender, and relationships content as they attempted to understand the role of the health teacher. They grappled with their role in shaping students’ moral character and navigating the concept of neutrality in schools. The teachers in this study believed their work had significantly changed due to the recent curriculum reform and they expressed a need for increased assistance, guidance, and support. The introduction of new content into the health curriculum left many teachers feeling overwhelmed and confused, with most regarding the task of re-interpretation to be of utmost importance.

In addition to the teachers feeling unsure as to what to say, in particular, with regard to gender and sexuality, they generally felt unsupported and were conscious of the extremely low value that was being placed on health education by parents and school leaders. This finding is supported by Lodge et al. (2022), who reported that, in Ireland, teachers often undertake sexuality teaching with little or no specialist professional development and a lack of sufficient direction from the state (or national) curriculum bodies.

Several implications arose from this study that may be useful for the improvement of the practice of curriculum reform and the teaching of health education. Health teachers need to explore their worldview to better articulate their personal perspectives. Interpretation guides should be developed for teachers and curriculum leaders to use when approaching the curriculum. Such guides should be context-specific to guide practitioners through the process of curriculum interpretation and help them determine their health education teaching perspectives. School leaders, particularly in faith-based schools, need to provide clarity for teachers as to how the PSCH content aligns with the school position or ethos. It is suggested that further research is undertaken to explore the self-awareness of teachers, their worldview, personal perspectives, teaching perspectives and intentions for action.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/youth5010004/s1.

Author Contributions

Writing, E.L.; Supervision, J.B.-B.; Supervision, P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted with ethics approval from the Higher Education Ethics Panel at the Alphacrucis University College, March 2020, the approval code is EC00466.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barbagallo, M., & Boon, H. (2012). Young people’s perceptions of sexuality and relationships education in Queensland schools. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 22(1), 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, A., Gillard, J., Firth, V., Scrymour, M., Welford, R., Lomax-Smith, J., Bartlett, D., Pike, B., & Constable, E. (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young australians deputy prime minister and minister for education, minister for employment and workplace relations, minister for social inclusion (Australian government) the Hon. Verity Firth MP The Hon. March. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED534449.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Barwood, D. M., Cunningham, C., & Penney, D. (2016). What we know, what we do and what we could do: Creating an understanding of the delivery of health education in lower secondary government schools in Western Australia. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41(11), 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory. A practical guide through qualitative analysis (M. Bloor, B. Czarniawska, N. Denzin, B. Glassner, A. Murcott, & J. Potter, Eds.). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2012). Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft (pp. 347–366). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2015). Teaching Theory Construction with Initial Grounded Theory Tools: A Reflection on Lessons and Learning. Qualitative Health Research, 25(12), 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliff, K. P., Wright, J., & Clarke, D. (2009). What does a socio-cultural perspective mean in Health and Physical Education? In Health and Physical Education: Issues for curriculum in Australia and New Zealand (pp. 165–179). Oxford University Press Australia and New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, C. Z. (2018). Applying dialogic pedagogy: A case study of discussion-based teaching. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, J., & Dowson, M. (2008). Beyond Transmissional Pedagogies in Christian Education: One School’s Recasting of Values Education. Journal of Research on Christian Education, 17(2), 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier-Harris, C. A., & Goldman, J. D. G. (2017). Is puberty education evident in Australia’s first national curriculum? Sex Education, 17(1), 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, K., & Wiltshire, K. (2014). Review of the Australian curriculum: Final report. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/australian-curriculum/resources/review-australian-curriculum-final-report-2014 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Eisenberg, M. E., Madsen, N., Oliphant, J. A., & Sieving, R. E. (2013). Barriers to Providing the Sexuality Education That Teachers Believe Students Need. Journal of School Health, 83(5), 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fincham, D. (2007). Citizenship and Personal, Social and Health Education in Catholic Secondary Schools: Stakeholders’ Views. Pastoral Care in Education: An International Journal for Pastoral Care & Personal-Social Education, 25(2), 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K., McGlashan, H., Tirumalai, V., Fenaughty, J., & Veukiso-Ulugia, A. (2022). Relationships and sexuality education: Key research informing New Zealand curriculum policy. Health Education Journal, 81(2), 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P., & Lindner, P. (2022). Educating Children about Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Australia Post-Marriage Equality. Human Rights Education Review, 5(2), 4–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannikas, C. (2022). Developing students’ digital literacy skills. Available online: https://www.structural-learning.com/post/developing-students-digital-literacy (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Gibson, S. E. (2009). Creating controversy: Sex education and the Christian right in South Australia. Available online: https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/60564/8/02whole.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Glanzer, P. L., & Ream, T. C. (2008). Educating Different Types of Citizens: Identity, Tradition, and Moral Education. Journal of College and Character, 9(4), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanzer, P. L., & Talbert, T. (2005). The impact and implications of faith or worldview in the classroom. Journal of Research in Character Education, 3(1), 25. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (1st ed., Vol. 6). Rutgers. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, B. (2005). A Talking Point at Last: Values Education in Schools. Journal of Christian Education, 48(3), 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelm, J. R. (2010). The dimensions of health: Conceptual models. p. 98. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Dimensions_of_Health.html?id=K9f2q7IeKu0C (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Lambert, K. (2018). Practitioner initial thoughts on the role of the five propositions in the new Australian Curriculum Health and Physical Education. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 9(2), 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, E. (2022). The interrelationship between a teacher’s worldview, personal beliefs, and the delivery of the Personal, Social and Community Health Strand of the Western Australian Health and Physical Education Curriculum, within secondary schools [Doctoral Dissertation, Alphacrucis University College]. Alphacrucis University College Research Repository. Available online: https://ac.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/61ALC_INST/1cv3ojh/alma991001209248006816 (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Lodge, A., Duffy, M., & Feeney, M. (2022). ‘I think it depends on who you have, I was lucky I had a teacher who felt comfortable telling all this stuff’. Teacher comfortability: Key to high-quality sexuality education? Irish Educational Studies, 43(2), 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttenberg, J., van Veen, K., & Imants, J. (2013). Looking for cohesion: The role of search for meaning in the interaction between teacher and reform. Research Papers in Education, 28(3), 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyle, J. (2013). The reality of reform: Teachers reflecting on curriculum reform in Western Australia. Available online: http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/698 (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Lynch, T. (2014, December 18–20). On the front foot: An Australian Health and Physical Education (HPE) perspective [Conference session]. 56th International Council Health, Physical Education, Recreation, Sport and Dance (ICHPER-SD) Anniversary World Congress & Exposition, Manama, Bahrain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D. (2014). Sacred ties and fresh eyes: Voicing critical public health perspectives in curriculum-making. Critical Public Health, 24(2), 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, C. (2014). Critical pedagogy in health education. Health Education Journal, 73(5), 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, C. (2022). LGBTQ youth and education: Policies and practices. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCuaig, L., & Hay, P. J. (2013). Towards an understanding of fidelity within the context of school-based health education. Critical Public Health, 24, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R. J. (2019). Personal Story Sharing as an Engagement Strategy to Promote Student Learning. Penn GSE Perspectives on Urban Education, 16(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, E. (2017). An investigation of teachers’ curriculum interpretation and implementation in a Queensland school [Doctoral Dissertation, Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology]. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D., & Billingham, J. (2018). A Systematic Framework for Exploring Worldviews and Its Generalization as a Multi-Purpose Inquiry Framework. Systems, 6(3), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCSA (School Curriculum and Standards Authority). (2016). Health and physical education. Available online: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/teaching/curriculum-browser/health-and-physical-education (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Shelley, K., & McCuaig, L. (2018). Close encounters with critical pedagogy in socio-critically informed health education teacher education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sire, J. W. (2015). Naming the elephant: Worldview as a concept (2nd ed.). Intervarsity Press USA. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A., Schlichthorst, M., Mitchell, A., Walsh, J., Lyons, A., Blackman, P., & Pitts, M. (2011). Sexuality education in australian secondary schools—Results of the 1st national survey of australian secondary teachers of sexuality education 2010 sexuality education in australian secondary schools (Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society Ed.). La Trobe University. Available online: https://www.latrobe.edu.au/arcshs (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tsybulsky, D., & Levin, I. (2019). Science teachers’ worldviews in the age of the digital revolution: Structural and content analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wichelen, T., Verhoeven, E., & Hau, P. (2023). The Genderbread Person: Mapping the social media debate about inclusive sexuality education. Sex Education, 24(5), 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, G., Finch, T., Giles, E. L., & Newbury-Birch, D. (2017). Exploring the factors affecting the implementation of tobacco and substance use interventions within a secondary school setting: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 12(1), 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. (2012). Health education: Theoretical concepts, effective strategies and core competencies: A foundation document to guide capacity development of health educators/World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, J. (2006). Why Some Teachers Resist Change and What Principals Can Do About It. NASSP Bulletin, 90(3), 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).