Digital Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Scaling and Effectiveness of Technology-Enabled Interventions: What technology-enabled adolescent SRH behavior change interventions have been scaled in LMICs, and what evidence exists regarding their effectiveness?

- Adolescents’ Preferences for Digital Program Delivery: What does the literature reveal about adolescents’ preferences and engagement with digital SRH programs?

- Investment and Development of Digital SRH Interventions: What insights can be gained regarding the level and types of investments organizations make to develop and deliver digital adolescent SRH behavior change interventions?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

- Types of Evaluations: We included studies featuring process evaluations, quasi-experimental and experimental evaluations, as well as cost or cost-effectiveness evaluations.

- Case Studies: Case studies were included if they provided substantial qualitative or quantitative information to answer the research questions.

- Literature Types: Both peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed literature, such as reports and briefs, were considered.

- Study Designs: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies were included to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

- Publication Date: Only studies published from 2010 to 2023 were included to reflect the most recent developments in technology and SRH.

- Geographic Scope: The focus was on interventions conducted in LMICs as classified by the World Bank (World Bank Open Data, n.d.).

- Participant Age Range: Studies involving participants aged 10–24 years were included to cover the adolescent and young adult population.

- Intervention Type: We included technology-enabled interventions utilizing cell phones, computers, and tablets but excluded those relying on mass media communications such as radio or television.

- Language: Only English-language papers were included to maintain consistency in data interpretation.

- Exclusions: Protocol papers (those outlining research plans without results), dissertations, and theses were excluded.

2.2. Search Keywords and Databases

- Age Range Keywords: Adolescent, Youth, Teen, Young Adult.

- Topic Keywords: Sexual and Reproductive Health, Family Planning, Contraception, Sexually Transmitted Disease, STD, SRH, HIV, AIDS, Health Education, Health Information, Female Genital Mutilation, FGM, Female Circumcision.

- Location Keywords: Developing Country, Global South, Third World, Less Developed Country, Low Income Country, Middle Income Country, Brazil, Guinea, India, Africa, Latin America, South America, Central America, Pakistan, Southeast Asia, China.

- Technology Keywords: Technology, Cell Phone, Cellular, Tablet, Computer, Online, mHealth.

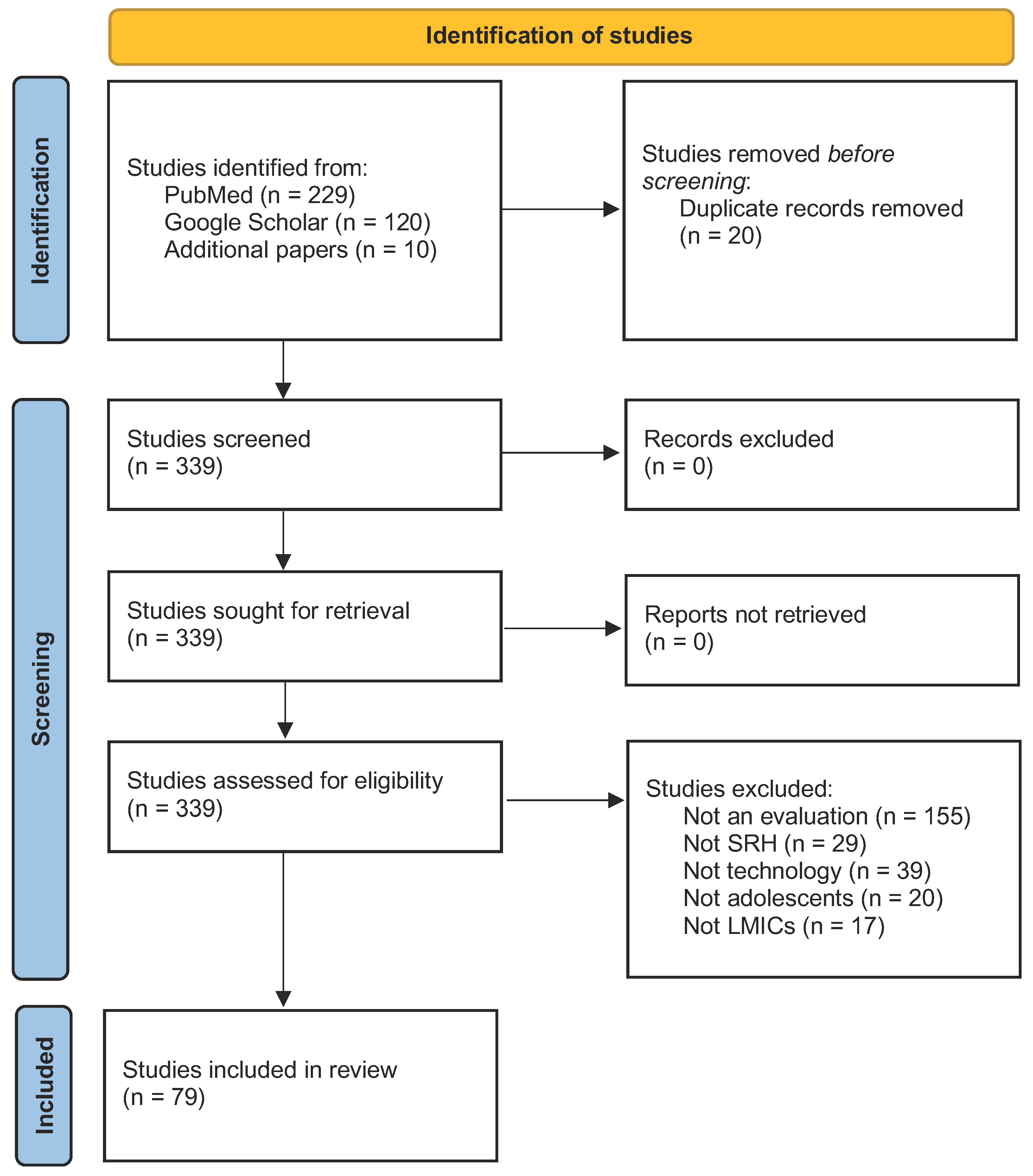

2.3. Study Selection and Screening Process

- Title and Abstract Screening: Titles and abstracts were reviewed for relevance based on the inclusion criteria. Studies that did not meet the criteria were excluded.

- Full-Text Review: Full texts of the remaining papers were thoroughly reviewed to confirm eligibility. Studies that failed to meet the inclusion criteria upon full-text review were excluded.

- Data Extraction: Relevant data were systematically extracted from the included studies, focusing on study design, intervention details, outcomes, and key findings.

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Types of Studies Analyzed

3.2. Types of Interventions Analyzed

3.3. Effectiveness (Research Question One)

3.4. Adolescent Preferences (Research Question Two)

3.5. Types of Investments (Research Question Three)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, R. M., Riess, H., Massey, P. M., Gipson, J. D., Prelip, M. L., Dieng, T., & Glik, D. C. (2017). Understanding where and why Senegalese adolescents and young adults access health information: A mixed methods study examining contextual and personal influences on health information seeking. Journal of Communication in Healthcare, 10(2), 116–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahonkhai, A. A., Pierce, L. J., Mbugua, S., Wasula, B., Owino, S., Nmoh, A., Idigbe, I., Ezechi, O., Amaral, S., David, A., Okonkwo, P., Dowshen, N., & Were, M. C. (2021). PEERNaija: A gamified mHealth behavioral intervention to improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment among adolescents and young adults in Nigeria. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 3, 656507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ames, H. M., Glenton, C., Lewin, S., Tamrat, T., Akama, E., & Leon, N. (2019). Clients’ perceptions and experiences of targeted digital communication accessible via mobile devices for reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10, CD013447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atujuna, M., Simpson, N., Ngobeni, M., Monese, T., Giovenco, D., Pike, C., Figerova, Z., Visser, M., Biriotti, M., Kydd, A., & Bekker, L.-G. (2021). Khuluma: Using participatory, peer-led and digital methods to deliver psychosocial support to young people living with HIV in South Africa. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 3, 687677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, T., Ronen, K., Copley, C., Guthrie, B., & Grant, E. (2020). Internet protocol messaging for global health: The IP4GH case study series. Gates Open Res, 4(54), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergam, S., Sibaya, T., Ndlela, N., Kuzwayo, M., Fomo, M., Goldstein, M. H., Marconi, V. C., Haberer, J. E., Archary, M., & Zanoni, B. C. (2022). “I am not shy anymore”: A qualitative study of the role of an interactive mHealth intervention on sexual health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of South African adolescents with perinatal HIV. Reproductive Health, 19, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahme, R., Mamulwar, M., Rahane, G., Jadhav, S., Panchal, N., Yadav, R., & Gangakhedkar, R. (2020). A qualitative exploration to understand the sexual behavior and needs of young adults: A study among college students of Pune, India. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 87(4), 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, C., Chhoun, P., Tuot, S., Fehrenbacher, A. E., Moran, A., Swendeman, D., & Yi, S. (2022). A mobile intervention to link young female entertainment workers in Cambodia to health and gender-based violence services: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(1), e27696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, S., Nabembezi, D., Birungi, R., Kiwanuka, J., & Ybarra, M. (2010). Cyber-Senga: Ugandan youth preferences for content in an internet-delivered comprehensive sexuality education programme. East African Journal of Public Health, 7(1), 58–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chukwu, E., Gilroy, S., Addaquay, K., Jones, N. N., Karimu, V. G., Garg, L., & Dickson, K. E. (2021). Formative study of mobile phone use for family planning among young people in Sierra Leone: Global systematic survey. JMIR Formative Research, 5(11), e23874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, R., Woods, N. F., Unger, J. A., Kinuthia, J., Matemo, D., Farid, S., Begnel, E. R., Kohler, P., & Drake, A. L. (2019). Acceptability, feasibility and utility of a Mobile health family planning decision aid for postpartum women in Kenya. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakwa, D., Mudzengerere, F. H., Mpofu, M., Tachiwenyika, E., Mudokwani, F., Ncube, B., Pfupajena, M., Nyagura, T., Ncube, G., & Tafuma, T. A. (2021). Use of mHealth solutions for improving access to adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health services in resource-limited settings: Lessons from Zimbabwe. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 3, 656351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endehabtu, B., Weldeab, A., Were, M., Lester, R., Worku, A., & Tilahun, B. (2018). Mobile phone access and willingness among mothers to receive a text-based mHealth intervention to improve prenatal care in northwest Ethiopia: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 1(2), e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatori, D., Argeu, A., Brentani, H., Chiesa, A., Fracolli, L., Matijasevich, A., Miguel, E. C., & Polanczyk, G. (2020). Maternal parenting electronic diary in the context of a home visit intervention for adolescent mothers in an urban deprived area of São Paulo, Brazil: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(7), e13686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feroz, A. S., Ali, N. A., Khoja, A., Asad, A., & Saleem, S. (2021). Using mobile phones to improve young people sexual and reproductive health in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review to identify barriers, facilitators, and range of mHealth solutions. Reproductive Health, 18(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gichangi, P., Gonsalves, L., Mwaisaka, J., Thiongo, M., Habib, N., Waithaka, M., Tamrat, T., Agwanda, A., Sidha, H., Temmerman, M., & Say, L. (2022). Busting contraception myths and misconceptions among youth in Kwale County, Kenya: Results of a digital health randomised control trial. BMJ Open, 12(1), e047426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glik, D., Massey, P., Gipson, J., Dieng, T., Rideau, A., & Prelip, M. (2016). Health-related media use among youth audiences in Senegal. Health Promotion International, 31(1), 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M., Archary, M., Adong, J., Haberer, J. E., Kuhns, L. M., Kurth, A., Ronen, K., Lightfoot, M., Inwani, I., John-Stewart, G., Garofalo, R., & Zanoni, B. C. (2023). Systematic review of mhealth interventions for adolescent and young adult hiv prevention and the adolescent hiv continuum of care in low to middle income countries. AIDS and Behavior, 27, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsalves, L., Njeri, W. W., Schroeder, M., Mwaisaka, J., & Gichangi, P. (2019). Research and implementation lessons learned from a youth-targeted digital health randomized controlled trial (the ARMADILLO study). JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7(8), e13005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenleaf, A. R., Ahmed, S., Moreau, C., Guiella, G., & Choi, Y. (2019). Cell phone ownership and modern contraceptive use in Burkina Faso: Implications for research and interventions using mobile technology. Contraception, 99(3), 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffee, K., Martin, R., Chory, A., & Vreeman, R. (2022). A systematic review of digital interventions to improve ART adherence among youth living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Research and Treatment, 2022, 9886306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacking, D., Mgengwana-Mbakaza, Z., Cassidy, T., Runeyi, P., Duran, L. T., Mathys, R. H., & Boulle, A. (2019). Peer mentorship via mobile phones for newly diagnosed HIV-positive youths in clinic care in Khayelitsha, South Africa: Mixed methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(12), e14012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henwood, R., Patten, G., Barnett, W., Hwang, B., Metcalf, C., Hacking, D., & Wilkinson, L. (2016). Acceptability and use of a virtual support group for HIV-positive youth in Khayelitsha, Cape Town using the MXit social networking platform. AIDS Care, 28(7), 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Torres, J. L., Benavides-Torres, R. A., Moreno-Monsiváis, M. G., Rodríguez-Vázquez, N., Martínez-Cervantes, R., & Cárdenas-Cortés, A. M. (2022). Use of smartphones to increase safe sexual behavior in youths at risk for HIV. International Journal of Psychological Research, 15(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J., McGinn, J., Cairns, J., Free, C., & Smith, C. (2020). A mobile phone-based support intervention to increase use of postabortion family planning in Cambodia: Cost-effectiveness evaluation. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(2), e16276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z., Fu, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, H., Guo, F., Hee, J., & Tang, K. (2023). Effects of sexuality education on sexual knowledge, sexual attitudes, and sexual behaviors of youths in China: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescent Health, 72(4), 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-Y., Kumar, M., Cheng, S., Urcuyo, A. E., & Macharia, P. (2022). Applying technology to promote sexual and reproductive health and prevent gender based violence for adolescents in low and middle-income countries: Digital health strategies synthesis from an umbrella review. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibegbulam, I. J., Akpom, C. C., Enem, F. N., & Onyam, D. I. (2018). Use of the Internet as a source for reproductive health information seeking among adolescent girls in secondary schools in Enugu, Nigeria. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 35(4), 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ippoliti, N. B., & L’Engle, K. (2017). Meet us on the phone: Mobile phone programs for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in low-to-middle income countries. Reproductive Health, 14(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, O., Wambua, S., Mwaisaka, J., Bossier, T., Thiongo, M., Michielsen, K., & Gichangi, P. (2019). Evaluation of the ELIMIKA pilot project: Improving ART adherence among HIV positive youth using an eHealth intervention in Mombasa, Kenya. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 23(1), 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamison, J., Karlan, D. S., & Raffler, P. (2013). Mixed method evaluation of a passive mHealth sexual information testing service in Uganda. Center discussion papers. (Article 150383). Economic Growth Center, Yale University. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org//p/ags/yaleeg/150383.html (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Karusala, N., Seeh, D. O., Mugo, C., Guthrie, B., Moreno, M. A., John-Stewart, G., Inwani, I., Anderson, R., & Ronen, K. (2021, May 8–13). “That courage to encourage”: Participation and aspirations in chat-based peer support for youth living with HIV. 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–17), Yokohama, Japan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharono, B., Kaggiah, A., Mugo, C., Seeh, D., Guthrie, B. L., Moreno, M., John-Stewart, G., Inwani, I., & Ronen, K. (2022). Mobile technology access and use among youth in Nairobi, Kenya: Implications for mobile health intervention design. mHealth, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laidlaw, R., Dixon, D., Morse, T., Beattie, T. K., Kumwenda, S., & Mpemberera, G. (2017). Using participatory methods to design an mHealth intervention for a low income country, a case study in Chikwawa, Malawi. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 17(1), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. H., Nurmatov, U. B., Nwaru, B. I., Mukherjee, M., Grant, L., & Pagliari, C. (2016). Effectiveness of mHealth interventions for maternal, newborn and child health in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Global Health, 6(1), 010401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Engle, K., Plourde, K. F., & Zan, T. (2017). Evidence-based adaptation and scale-up of a mobile phone health information service. mHealth, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- L’Engle, K. L., Mangone, E. R., Parcesepe, A. M., Agarwal, S., & Ippoliti, N. B. (2016). Mobile phone interventions for adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 138(3), e20160884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C., Ramirez, D. C., Valenzuela, J. I., Arguello, A., Saenz, J. P., Trujillo, S., Correal, D. E., Fajardo, R., & Dominguez, C. (2014). Sexual and reproductive health for young adults in Colombia: Teleconsultation using mobile devices. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 2(3), e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCarthy, S., Wagner, Z., Mendoza-Graf, A., Gutierrez, C. I., Samba, C., Birungi, J., Okoboi, S., & Linnemayr, S. (2020). A randomized controlled trial study of the acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary impact of SITA (SMS as an Incentive To Adhere): A mobile technology-based intervention informed by behavioral economics to improve ART adherence among youth in Uganda. BMC Infectious Diseases, 20, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macharia, P., Pérez-Navarro, A., Inwani, I., Nduati, R., & Carrion, C. (2021). An exploratory study of current sources of adolescent sexual and reproductive health information in Kenya and their limitations: Are mobile phone technologies the answer? International Journal of Sexual Health, 33(3), 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangone, E. R., Lebrun, V., & Muessig, K. E. (2016). Mobile phone apps for the prevention of unintended pregnancy: A systematic review and content analysis. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(1), e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathenjwa, T., Nkosi, B., Kim, H.-Y., Bain, L. E., Tanser, F., & Wassenaar, D. (2023). Ethical considerations in using a smartphone-based GPS app to understand linkages between mobility patterns and health outcomes: The example of HIV risk among mobile youth in rural South Africa. Developing World Bioethics, 23(4), 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, O. L., Aliaga, C., Torrico Palacios, M. E., López Gallardo, J., Huaynoca, S., Leurent, B., Edwards, P., Palmer, M., Ahamed, I., & Free, C. (2020). An intervention delivered by mobile phone instant messaging to increase acceptability and use of effective contraception among young women in Bolivia: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e14073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meherali, S., Rehmani, M., Ali, S., & Lassi, Z. S. (2021). Interventions and strategies to improve sexual and reproductive health outcomes among adolescents living in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adolescents, 1(3), 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaisaka, J., Gonsalves, L., Thiongo, M., Waithaka, M., Sidha, H., Alfred, O., Mukiira, C., & Gichangi, P. (2021). Young people’s experiences using an on-demand mobile health sexual and reproductive health text message intervention in Kenya: Qualitative study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(1), e19109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalwanga, R., Nuwamanya, E., Nuwasiima, A., Babigumira, J. U., Asiimwe, F. T., & Babigumira, J. B. (2021). Utilization of a mobile phone application to increase access to sexual and reproductive health information, goods, and services among university students in Uganda. Reproductive Health, 18(1), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigenda, G., Torres, M., Jáuregui, A., Silverman-Retana, J. O., Casas, A., & Servan-Mori, E. (2016). Health information technologies for sexual and reproductive health: Mapping the evidence in Latin America and the Caribbean. Journal of Public Health Policy, 37(Suppl. S2), 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuwamanya, E., Nalwanga, R., Nuwasiima, A., Babigumira, J. U., Asiimwe, F. T., Babigumira, J. B., & Ngambouk, V. P. (2020). Effectiveness of a mobile phone application to increase access to sexual and reproductive health information, goods, and services among university students in Uganda: A randomized controlled trial. Contraception and Reproductive Medicine, 5(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, B. M., Smith, L., Orton, B., Hayter, M., Kaseje, M., Wafula, C. O., Ocholla, P., Onukwugha, F., & Kaseje, D. C. O. (2022). Perspectives of adolescents, parents, service providers, and teachers on mobile phone use for sexual reproductive health education. Social Sciences, 11(5), 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M. J., Henschke, N., Villanueva, G., Maayan, N., Bergman, H., Glenton, C., Lewin, S., Fønhus, M. S., Tamrat, T., Mehl, G. L., & Free, C. (2020). Targeted client communication via mobile devices for improving sexual and reproductive health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8, CD013680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, C., Kleeb, M., Mbelwa, A., & Ahorlu, C. (2014). The use of social media among adolescents in Dar es Salaam and Mtwara, Tanzania. Reproductive Health Matters, 22(43), 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela, A., Stevenson, J., Hinton, R., Emler, M., Tsoli, S., & Snilstveit, B. (2017). Social, behavioural and community engagement interventions for reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health: An evidence gap map (2017th ed.). International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, P. R., van Teijlingen, E. R., Silwal, R. C., & Dhital, R. (2022). Role of social media for sexual communication and sexual behaviors: A focus group study among young people in Nepal. Journal of Health Promotion, 10(1), 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C., Sutherland, M. A., & Palacios, I. (2019). Exploring the use of technology for sexual health risk-reduction among ecuadorean adolescents. Annals of Global Health, 85(1), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, P. (2014). m4RH impact evaluation design considerations. Available online: https://lib.digitalsquare.io/server/api/core/bitstreams/6e1721b8-ae56-492f-8079-30271cfd4f96/content (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Rodrigues, R., Bogg, L., Shet, A., Kumar, D. S., & De Costa, A. (2014). Mobile phones to support adherence to antiretroviral therapy: What would it cost the Indian National AIDS Control Programme? Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(1), 19036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokicki, S., Cohen, J., Salomon, J. A., & Fink, G. (2017). Impact of a text-messaging program on adolescent reproductive health: A cluster–randomized trial in Ghana. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabben, G., Mudhune, V., Ondeng’e, K., Odero, I., Ndivo, R., Akelo, V., & Winskell, K. (2019). A smartphone game to prevent HIV among young Africans (Tumaini): Assessing intervention and study acceptability among adolescents and their parents in a randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7(5), e13049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexual & Reproductive Health. (n.d.). United Nations Population Fund. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sexual-reproductive-health (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Sharma, A., Mwamba, C., Ng’andu, M., Kamanga, V., Mendamenda, M. Z., Azgad, Y., Jabbie, Z., Chipungu, J., & Pry, J. M. (2022). Pilot implementation of a user-driven, web-based application designed to improve sexual health knowledge and communication among young Zambians: Mixed methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(7), e37600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C., Ngo, T. D., Gold, J., Edwards, P., Vannak, U., Sokhey, L., Machiyama, K., Slaymaker, E., Warnock, R., McCarthy, O., & Free, C. (2015). Effect of a mobile phone-based intervention on post-abortion contraception: A randomized controlled trial in Cambodia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 93(12), 842–850A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somefun, O. D., Casale, M., Haupt Ronnie, G., Desmond, C., Cluver, L., & Sherr, L. (2021). Decade of research into the acceptability of interventions aimed at improving adolescent and youth health and social outcomes in Africa: A systematic review and evidence map. BMJ Open, 11(12), e055160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S., Mercer, M. A., Hofstee, M., Stover, B., Vasconcelos, P., & Meyanathan, S. (2019). Connecting mothers to care: Effectiveness and scale-up of an mHealth program in Timor-Leste. Journal of Global Health, 9(2), 020428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J. A., Ronen, K., Perrier, T., DeRenzi, B., Slyker, J., Drake, A. L., Mogaka, D., Kinuthia, J., & John-Stewart, G. (2018). Short message service communication improves exclusive breastfeeding and early postpartum contraception in a low- to middle-income country setting: A randomised trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 125(12), 1620–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahdat, H. L., L’Engle, K. L., Plourde, K. F., Magaria, L., & Olawo, A. (2013). There are some questions you may not ask in a clinic: Providing contraception information to young people in Kenya using SMS. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 123(Suppl. S1), e2–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, W. D. F., Fischer, A., Lalla-Edward, S. T., Coleman, J., Lau Chan, V., Shubber, Z., Phatsoane, M., Gorgens, M., Stewart-Isherwood, L., Carmona, S., & Fraser-Hurt, N. (2019). Improving linkage to and retention in care in newly diagnosed HIV-positive patients using smartphones in South Africa: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7(4), e12652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, L., Ahmed, T., Scott, N., Akter, S., Standing, H., & Rasheed, S. (2018). ‘We have the internet in our hands’: Bangladeshi college students’ use of ICTs for health information. Globalization and Health, 14(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldman, L., & Stevens, M. (2015, February 1). Sexual and reproductive health rights and information and communications technologies: A policy review and case study from South Africa. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Sexual-and-Reproductive-Health-Rights-and-and-A-and-Waldman-Stevens/67998cae7aa03ccee8f62272e3e78fc689395bde (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Wang, H., Gupta, S., Singhal, A., Muttreja, P., Singh, S., Sharma, P., & Piterova, A. (2022). An artificial intelligence chatbot for young people’s sexual and reproductive health in India (SnehAI): Instrumental case study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(1), e29969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winskell, K., Sabben, G., Akelo, V., Ondeng’e, K., Obong’o, C., Stephenson, R., Warhol, D., & Mudhune, V. (2018). A smartphone game-based intervention (Tumaini) to prevent HIV among young africans: Pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 6(8), e10482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winskell, K., Sabben, G., Ondeng’e, K., Odero, I., Akelo, V., & Mudhune, V. (2019). A smartphone game to prevent HIV among young Kenyans: Household dynamics of gameplay in a feasibility study. Health Education Journal, 78(5), 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank Open Data. (n.d.). World Bank Group. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Ybarra, M. L., Agaba, E., Chen, E., & Nyemara, N. (2020). Iterative development of In This toGether, the first mHealth HIV prevention program for older adolescents in Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 24(8), 2355–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M. L., Biringi, R., Prescott, T., & Bull, S. S. (2012). Usability and navigability of an HIV/AIDS internet intervention for adolescents in a resource-limited setting. Computers, Informatics, Nursing: CIN, 30(11), 587–595; quiz 596–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, M. L., Bull, S. S., Prescott, T. L., Korchmaros, J. D., Bangsberg, D. R., & Kiwanuka, J. P. (2013). Adolescent abstinence and unprotected sex in CyberSenga, an Internet-based HIV prevention program: Randomized clinical trial of efficacy. PLoS ONE, 8(8), e70083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ybarra, M. L., Mwaba, K., Prescott, T. L., Roman, N. V., Rooi, B., & Bull, S. (2014). Opportunities for technology-based HIV prevention programming among high school students in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care, 26(12), 1562–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Impact | Finding | Citations | Number of Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Outcomes | |||

| Knowledge of SRH | Significantly improved | See: (Feroz et al., 2021; Hernández-Torres et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2023; Nuwamanya et al., 2020; Palmer et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2022) | 6 |

| Knowledge of SRH | Mixed: 2 of 17 HIV knowledge items improved | See: (Ivanova et al., 2019) | 13 |

| Knowledge of SRH | No significant change | See: (Jamison et al., 2013; Winskell et al., 2019) | 2 |

| Access to contraceptive information | Significantly improved | See: (Feroz et al., 2021) | 1 |

| Knowledge of contraception | Significantly improved | See: (Riley, 2014) | 1 |

| Knowledge of contraception | No significant change | See: (Gichangi et al., 2022) | 1 |

| Health Behaviors | |||

| Risky sexual behavior | Significantly reduced | See: (Hernández-Torres et al., 2022) | 1 |

| Risky sexual behavior | No significant change | See: (Hu et al., 2023; Jamison et al., 2013; Lopez et al., 2014) | 3 |

| Condom use | Significantly increased | See: (Nuwamanya et al., 2020) | 1 |

| Condom use | No significant change | See: (Brody et al., 2022; Ybarra et al., 2013) | 2 |

| Contraceptive use | Significantly increased | See: (Nuwamanya et al., 2020; Palmer et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2015; Unger et al., 2018) | 4 |

| Contraceptive use | No significant change | See: (Riley, 2014) | 1 |

| Health Services | |||

| Completed referral to sexual or reproductive health or HIV appointment | Significantly increased | See: (Dhakwa et al., 2021) | 1 |

| HIV testing | Significantly increased | See: (Nuwamanya et al., 2020) | 1 |

| HIV testing | No significant change | See: (Brody et al., 2022) | 1 |

| Adherence to HIV treatment | Significantly increased | See: (Hacking et al., 2019) | 1 |

| Adherence to HIV treatment | Mixed: significantly increased 2 of 6 studied reviewed; others found no significant increase | See: (Griffee et al., 2022) | 1 |

| Adherence to HIV treatment | No significant change | See: (Goldstein et al., 2023; Ivanova et al., 2019; MacCarthy et al., 2020) | 3 |

| Facility births | Significantly increased | See: (Thompson et al., 2019) | 1 |

| Health Outcomes | |||

| HIV viral load suppression | No significant increase | See: (Hacking et al., 2019; Venter et al., 2019) | 2 |

| Pregnancy rates | No significant change | See: (Meherali et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2015) | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dowling, R.; Howell, E.M.; Dasco, M.A.; Schwartzman, J. Digital Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Youth 2025, 5, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010015

Dowling R, Howell EM, Dasco MA, Schwartzman J. Digital Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Youth. 2025; 5(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleDowling, Russell, Embry M. Howell, Mark Anthony Dasco, and Jason Schwartzman. 2025. "Digital Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review" Youth 5, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010015

APA StyleDowling, R., Howell, E. M., Dasco, M. A., & Schwartzman, J. (2025). Digital Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Youth, 5(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010015