Harm Reduction as a Complex Adaptive System: Results from a Qualitative Structural Analysis of Services Accessed by Young Heroin Users in Mauritius

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Humanism: Care is provided without moral judgement, recognising that context influences choices.

- Pragmatism: Focus on reducing immediate risks.

- Individualism: Acknowledgment that individuals have unique needs and strengths.

- Autonomy: The right to make informed choices, even if they go against expert recommendations.

- Incrementalism: Any positive change is considered an improvement over the current situation.

- Accountability without Termination: Individuals have the right to make their own choices without losing access to services based on those decisions.

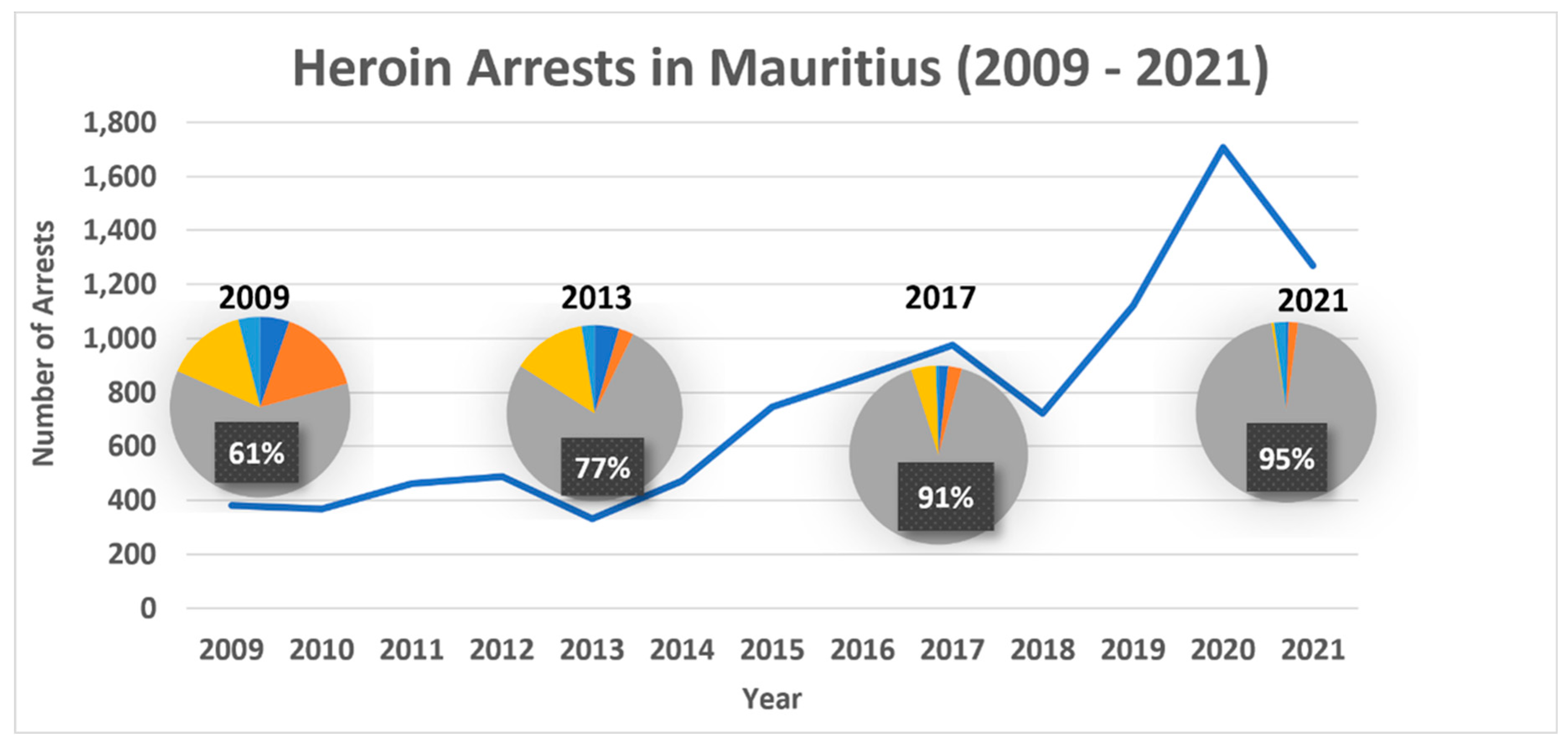

1.1. Injecting Drug Use and Infectious Diseases in Mauritius

1.2. Harm Reduction and Young People in Mauritius

1.3. The Evolving Harm Reduction Environment

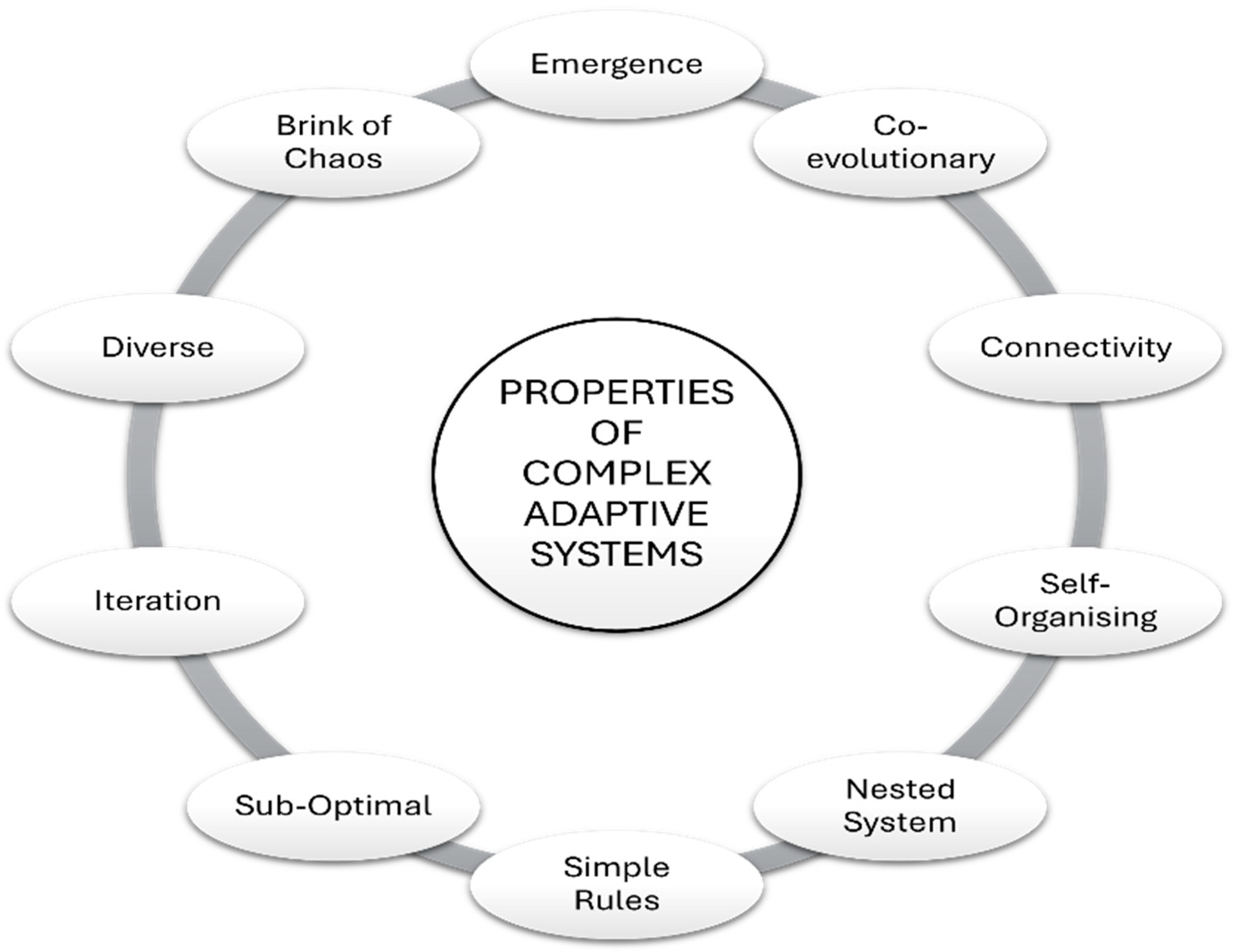

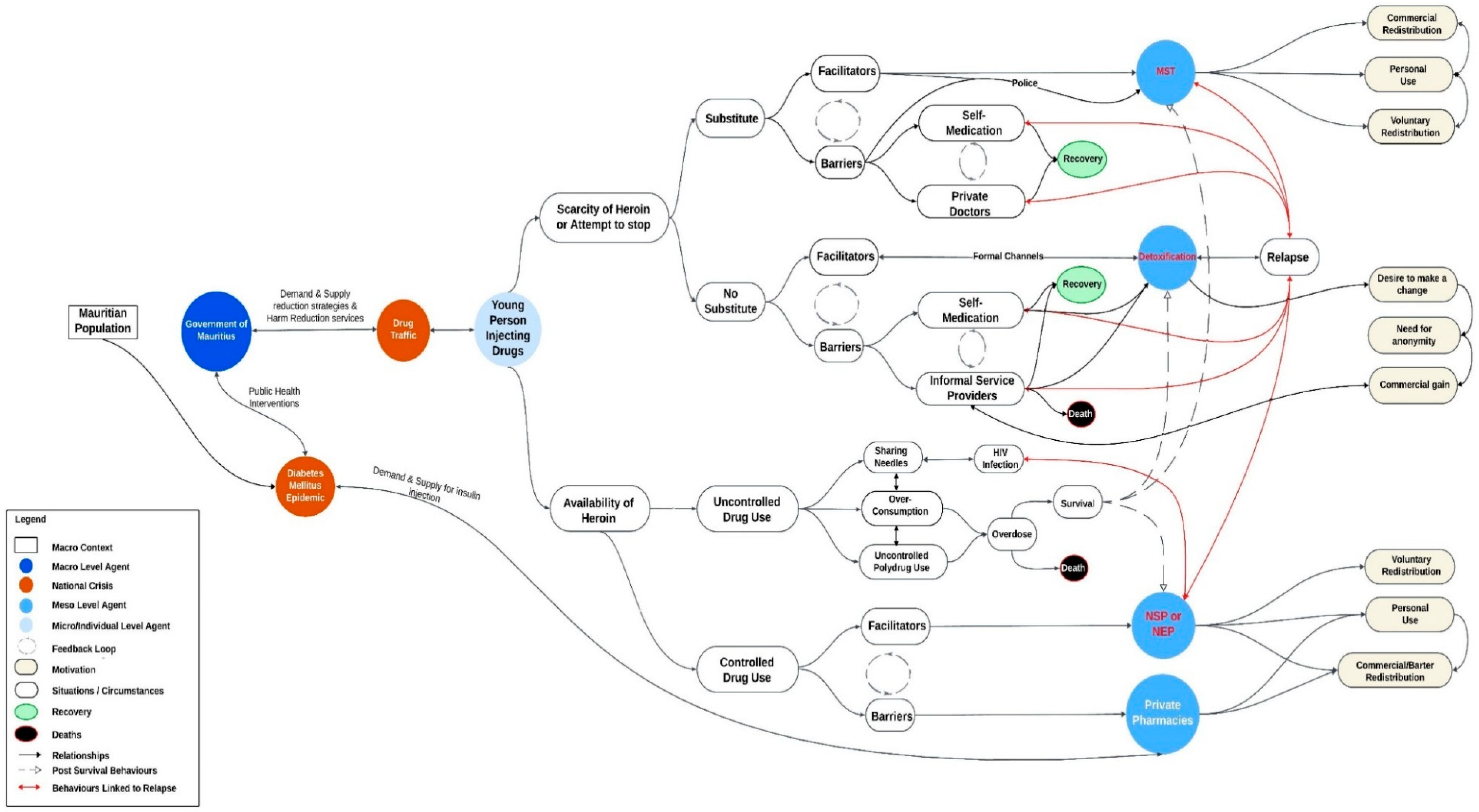

1.4. Mauritian Harm Reduction as a Complex Adaptive System

1.5. Aims and Objectives

- To understand the perceived facilitators and barriers to accessing HR services;

- To map the underlying dynamics within and between different HR services;

- To assess how to increase the effectiveness of HR services for young people.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analysis

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Access to Needles and Syringes

3.1.1. Facilitators for Accessing Needles and Syringes

3.1.2. Barriers to Needles and Syringes

3.1.3. Redistribution of Needles and Syringes

“The ones used for insulin. With the yellow cap… it has two yellow caps”F-P1

“Because if you don’t have a prescription, you’re buying it on the black market. Whereas when you have a prescription, they think you’re really ill. And that you need insulin.”M-P1

3.2. Access to Methadone Substitution Therapy

3.2.1. Facilitators for Methadone Substitution Therapy

“Whereas if you’re on methadone, you’re active, you can do whatever you want, you don’t need to use drugs”PL-P3

3.2.2. Barriers to MST

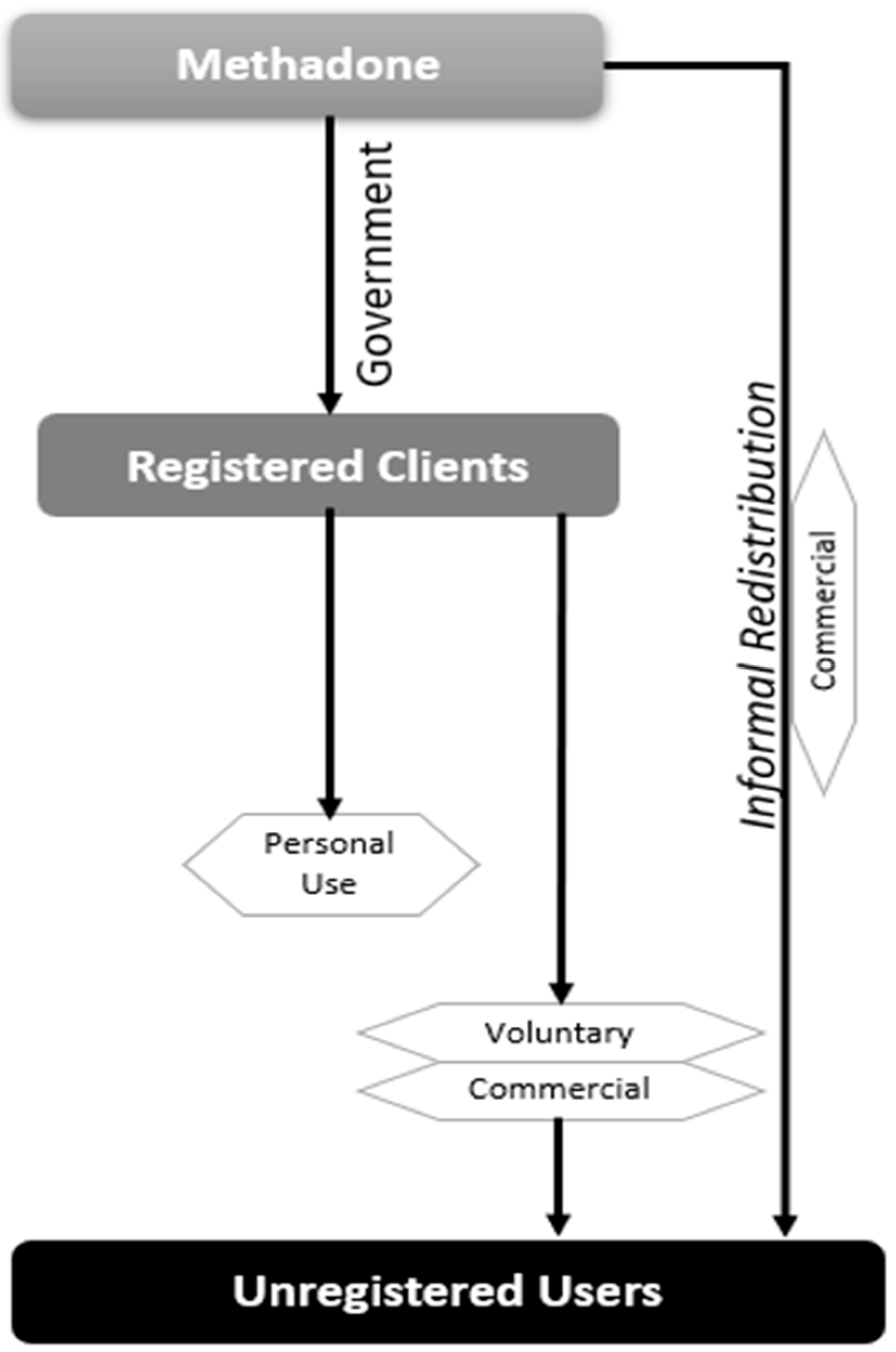

3.2.3. Redistribution of MST

3.3. Access to Detoxification and Rehabilitation

3.3.1. Facilitators for Detoxification and Rehabilitation

“No, something that I can take while I keep living a normal life, where I can work and do stuff.”BV-P2

3.3.2. Barriers to Detoxification and Rehabilitation Programmes

3.3.3. Informal Access to Detoxification and Rehabilitation

4. Discussion

4.1. Facilitators and Barriers to Accessing HR Services

4.2. Dynamics Within and Between Different HR Services

Complex Adaptive System Dynamics in Mauritian HR: Implications

4.3. Ways to Increase the Effectiveness of HR Services for Young People

4.4. Limitations and Reflections

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Informal HR Service Providers: Two Case Studies

Appendix A.1. Individual Case Study 1: Hit Doctor (HD) as Informal Service Provider

“I’ll tell you what’s wrong with it: So I went to jail for a month because I couldn’t pay a fine. So once I was there, there was no Subutex. And I was sick for a month. While with brown, if you don’t get it for three or four days, you’ll get sick, sure, but then you recover.”

“This is not something I’m proud of but I have to keep on using because otherwise I will be sick. That’s why I try to help the youth because even though I want to stop, I can’t. So I tell them, don’t do it. And then when I see them do things they’re not supposed to, like keeping used syringes, I tell them. Because I also used to do that and I know it’s wrong. That’s why when the people from CUT give out syringes, I take extra ones to give it to them later because they’re often not here when the distribution is happening. They are at work.”

Appendix A.2. Individual Case Study 2: Volunteer as Informal Service Provider

“hey, that’s too many and he asked whether I was dealing in them and I said no, no, no, no. I told him that my cousins use, that I have two (family members) who use and that I have friends who use and that I go and give them the clean syringes.”

“Yeah. The police… the police would wait for them and stop them, open the packaging of the syringe because like I told them, there’s no police case for having a new syringe. And they say that they open the packaging. So, they say they’d rather keep using their old syringe, that’s why they don’t want to exchange them for new ones.”

“And because I come to the centre, I have access to magazines and that’s how I learnt about the diseases… there are many diseases that can be caught. Through a syringe that… that you’ve used over and over again, the needle gets infected… but they won’t come and get new ones because of that”

“I think it is because… (unclear) people who talk. And they can’t talk to their friends because they’ll laugh at him. So, they keep it to themselves and they become depressed. Or if he’s done something bad in his life and has regrets. And this will always remain something that bothers him. Because when he’s not under the influence and he goes to sleep, this bothers him.”

“Energy drinks as well. Because… once a friend told me he had gone to a private doctor and the doctor gave him… valium as well as a pill for the aches and pains in the bones. But the doctor prescribed mostly oral vials (Force G). And then he gave him…calcium.”

“They’ve already convinced themselves that they have the disease. So they’ll continue to take drugs, they’ll tell you they don’t want to change, they don’t want children because they don’t want a child who’s infected. So they’d rather keep on using. But it’s not a given that they’re infected because they haven’t been tested. You understand?”

“They’re either greedy, they just want more, you understand? They know of the risk of an overdose. If… they know there’s a risk they could overdose. But they still do it.”

“I think especially those youngsters, they’re still teenagers, they don’t have… they don’t think. So you need people who have already been there, who know what this is about, to go and talk to them. To be able to make them listen, get tested and whatnot. It needs to be through people who have been there.”

Appendix B

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Illustrative Quote | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to HR | Perceived facilitators for accessing Needles and Syringes | Endorsement by peers | “Friends spoke to me and told me there was nothing wrong in going there and that nothing would happen” | BV-P4 |

| Non- judgmental interactions | “The people there, they’re nice. They don’t look down at you like you’re a drug addict, they don’t want to talk to you.” | F-P1 | ||

| Credibility of outreach staff | “Because they know, you see. They know how things work, we don’t have to pretend with them. They won’t ask obvious questions, because they know… they know what we’re doing. We just chat, how are you, good, yeah.” | F-P2 | ||

| Ease to register and free service | “Well, on the second day, I didn’t have any money and when I went, they registered me and gave me a card.” | BC-P1 |

Appendix C

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Illustrative Quote | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to HR | Perceived barriers to access Needles and Syringes | Timing and Geographic Coverage | “If I’m not home and the caravan comes, I’ll miss it.” | BV-P4 |

| Quality of Injecting Equipment | “Sometimes they give us tiny needles that can break in the veins. It’s happened to me before; I needed to open it up with a blade.” | BC-P1 | ||

| Arrests by Police | “If I go to the caravan to take some syringes and I take them home. What if as I’m taking the old ones back, the police arrest me? That’s a problem as they could charge me.” | F-P1 |

Appendix D

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Illustrative Quote | Participant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal HR Network Dynamics | Redistribution of Needles and Syringes | Commercial Motivation | “It’s more… they get their syringes… maybe a couple… the beneficiaries, they’ll take their share…. I know one beneficiary who would take his share and then sell it. He’s also a user but he will sell his syringes to people who ask him to.” | B-SP3 |

| Barter (semi- commercial motivation) | “No, I don’t ask for money. But they do give me something, a cigarette or something. Because you see, I also have the cravings and they give me some stuff.” | BDT-SP1 | ||

| Voluntary/ Altruistic motivation | “When we drove past … no some are registered, some aren’t. But I give them, when I have, I give them. Because I have never used somebody’s syringe. Nor… people… have I borrowed their syringes” | F-P2 |

Appendix E

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Illustrative Quote | Participant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to HR | Perceived facilitators for MST | Reducing withdrawal pains | “It stops the cravings. You don’t get sick. Because if you don’t take drugs, you get withdrawal symptoms. You’re on tenterhooks, you feel weak. You can’t do anything. Whereas if you’re on methadone, you’re active, you can do whatever you want, you don’t need to use drugs” | BM-P2 |

| Becoming less reliant on others | “They make me beg. The whole day I beg, send messages, mum, I’m dying, mum, come quick, bring the money, I can’t bear it and she keeps saying I’m coming, I’m coming. This is also what made me want to do my best to get out of this shit as soon as possible.” | PL-P1 | ||

| Desire to stop drug use completely | “No, I don’t want to take the methadone for the rest of my life. I will take it … the doctor will ask me whether I want to take the methadone for six months or for the rest of my life. I will take it for six months” | PL-P3 |

Appendix F

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Illustrative Quote | Participant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers to HR | Perceived barriers to MST | Side-effects | “It rots your teeth, it rots your bones. I have a friend who’s on methadone, her teeth are all rotten” | BM-P2 |

| Efficacy in treating addiction | “If I go on methadone, I will have to stay on methadone… there are also cravings that come with methadone. I’d rather stop on my own and not have any cravings for anything” | EC-P1 | ||

| Stigma & impact on family | “Yes, but like I told you, I don’t want people to know that I…” | BM-P3 |

Appendix G

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Illustrative Quote | Participant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal HR Networks Dynamics | Redistribution of methadone | Personal use | “And I have a friend who was on methadone but who needed money to buy drugs. So, I asked that person sometimes to sell it to me and when I take the methadone, I feel ok. And I don’t need to go and find money for the other thing.” | BdT-P2 |

| Insurance/ Commercial | “It means that the methadone is a barrier: the day you don’t want to take methadone and you want to use, you sell the methadone and you use the money to buy drugs.” | PL-P1 | ||

| Voluntary | “And instead of giving them drugs, I go and find something that will bring them some relief. To prevent them from getting sick. Then they ask me to get them a dose of methadone. I go get a dose” | PL-P2 |

Appendix H

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Illustrative Quote | Participant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to HR | Perceived facilitators for Detoxification and Rehabilitation | The desire to make a significant change | “I became a dad… I had a little boy and then I wanted to stop for myself. Because you know, this life is worse than a dog’s life. Nothing… and if I can’t look at myself in the mirror, what would my boy…” | CM-P1 |

| Encouragement from peers and Professionals | “A friend took me. He told me let’s go check it out” | BV-P5 | ||

| Tried and tested approach | “I don’t know, a friend went and he told me about it, told me the treatment was good there. They give you like this tablet called zamadol, you just dilute it in water and then I think he drinks it or takes it by the spoon, I don’t know. He told me I would be able to take it and I’d be able to sleep” | BV-P3 |

Appendix I

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Illustrative Quote | Participant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers to HR | Perceived barriers to Detoxification and Rehabilitation | Will power | “They’re saying I need to find the will to go and check into a centre (detox) but I say I don’t want to go to the centre. And not everybody has that willpower. I can say yes I’ll do it but it’s following it up with the act that matters and I don’t have the willpower.” | BDT-P2 |

| Fear of HIV infection | “Yeah. Had I had it, I would have wasted my life with drugs. I wouldn’t have told my family I had it. I wouldn’t have worried them.” | PL-P3 | ||

| Stigma and isolation | “They were criticizing me in a way I couldn’t open myself up to them because the way they were talking, a dog was better than a drug addict. That’s the way they saw things.” | M-P1 | ||

| Effectiveness of treatment and fear of failure | “No, I have been on a treatment where they reduce the dosage too quickly, at once – the first week, they prescribe a strong dosage and the second week, they just reduce it. And I was doing hard work every day, I was painting the whole day and it was tiring. And even though I took the pills, they had no effect on me.” | PL-P2 |

Appendix J

| Major Theme | Analytical Theme | Code | Illustrative Quote | Participant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal HR Networks Dynamics | Informal detoxification | Commercial | “There are…doctors who give you medication that can help with the cravings, the problems you get when you don’t use.” | F-P1 |

| Self-medication/ Self-reliance | “I was taking those oral phials as well as calcium. Vitamins as well” | GP-SP1 |

References

- Aronowitz, S., Behrends, C., Lowenstein, M., Schackman, B., & Weiner, J. (2022). Lowering the barriers to medication treatment for people with opioid use disorder: Evidence for a low-threshold approach. Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics. Available online: https://cherishresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Penn-LDI.CHERISH-Issue-Brief.January-2022.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Beletsky, L., Baker, P., Arredondo, J., Emuka, A., Goodman-Meza, D., Medina-Mora, M. E., Werb, D., Davidson, P., Amon, J. J., Strathdee, S., & Magis-Rodriguez, C. (2018). The global health and equity imperative for safe consumption facilities. The Lancet, 392(10147), 553–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissière, M. (2022). Methadone: Un traffic qui gagne du terrain. l’Express.mu. Available online: https://lexpress.mu/s/article/415014/methadone-un-trafic-qui-gagne-terrain (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Burman, C. J., & Aphane, A. A. (2016). Complex adaptive HIV/AIDS risk reduction: Plausible implications from findings in Limpopo Province, South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 106(6), 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, E. M., Jia, H., Shankar, A., Hanson, D., Luo, W., Masciotra, S., Owen, S. M., Oster, A. M., Galang, R. R., Spiller, M. W., & Blosser, S. J. (2017). Detailed transmission network analysis of a large opiate-driven outbreak of HIV infection in the United States. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 216(9), 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, K. S. (2005). Grounded theory methodology—Strauss’ version vs Glaserian version. Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14(1), 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collectif Urgence Toxida. (2010). Briefing to the committee on economic, social and cultural rights on the consolidated second-fourth reports of mauritius on the implementation of the international covenant on economic, social and cultural rights drug use, HIV/AIDS, and Harm reduction: Articles 2, 12 and 15.1.b submitted jointly by collectif urgence toxida and the international harm reduction association 1 March 2010. Available online: https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cescr/docs/ngos/IHRA_CUT_Mauritius44.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Collectif Urgence Toxida. (2023). Harm reduction information note-Mauritius. Available online: https://hri.global/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Mauritius-harm-reduction-note-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Collectif Urgence Toxida. (2024). Conference report: Support. Don’t punish 2024. Available online: https://idpc.net/news/2024/10/mauritius-support-don-t-punish-conference-report-2024 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Colledge-Frisby, S., Ottaviano, S., Webb, P., Grebely, J., Wheeler, A., Cunningham, E. B., Hajarizadeh, B., Leung, J., Peacock, A., Vickerman, P., Farrell, M., Dore, G. J., Hickman, M., & Degenhardt, L. (2024). Global coverage of interventions to prevent and manage drug-related harms among people who inject drugs: A systematic review. The Lancet Global Health, 11(5), e673–e683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H. L. (2015). War on Drugs Policing and Police Brutality. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(8–9), 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Defimedia.info. (2021). Réhabilitation: Une aile pour accros aux drogues synthétiques à l’hôpital Brown Séquard. Available online: https://defimedia.info/rehabilitation-une-aile-pour-accros-aux-drogues-synthetiques-lhopital-brown-sequard (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Defimedia.info. (2024). Programme de méthadone à partir de 15 ans: Entre trois et cinq adolescents font une demande chaque année. Available online: https://defimedia.info/programme-de-methadone-partir-de-15-ans-entre-trois-et-cinq-adolescents-font-une-demande-chaque-annee (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Defisante.mu. (2024). L’hôpital psychiatrique brown sequard: L’Orchidée drug treatment and rehabilitation centre dédié aux femmes. Available online: https://defisante.defimedia.info/actu-sante/lhopital-psychiatrique-brown-sequard-lorchidee-drug-treatment-and-rehabilitation-centre-dedie-aux-femmes/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Degenhardt, L., Peacock, A., Colledge, S., Leung, J., Grebely, J., Vickerman, P., Stone, J., Cunningham, E. B., Trickey, A., Dumchev, K., & Lynskey, M. (2017). Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: A multistage systematic review. The Lancet Global Health, 5(12), e1192–e1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D., Stöckl, T., Tin To, W., Langguth, B., & Vanneste, S. (2017). Non-invasive transcranial magnetic and electrical stimulation: Working mechanisms. In J. R. Evans, & R. P. Turner (Eds.), Rhythmic stimulation procedures in neuromodulation (pp. 193–223). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ExchangeRates.org.uk. (2017–2018). Historical currency calculator-United States dollar 2017–2018 to Mauritian Rupee 2017–2018. Available online: https://www.exchangerates.org.uk/historical-currency-converter.html (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Farber, D. (Ed.). (2022). The war on drugs: A history. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, R., & Klein, W. M. (2015). Risk perceptions and health behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A., & Krug, A. (2013). Excluding Youth? A global review of harm reduction services for young people. Available online: https://www.hri.global/files/2012/09/04/Chapter_3.2_youngpeople_.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Gilead. (2024). Gilead helps to put African nation on path to eliminate Hepatitis C. Available online: https://stories.gilead.com/articles/gilead-helps-put-african-nation-on-path-to-eliminate-hepatitis-c (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Mauritius. (2001). The dangerous drugs act 2000. Available online: https://health.govmu.org/health/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/DANGEROUS-DRUGS-ACT-2000-1.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Government of Mauritius. (2007). Revised laws of Mauritius: HIV and AIDS act, act 31 of 2006—3rd August 2007. Available online: https://health.govmu.org/health/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/HIV-AND-AIDS-ACT-2006-1-1.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Government of Mauritius. (2018). Commission of inquiry on drug trafficking report. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39269164/Commission_of_Enquiry_on_Drug_Trafficking_Report (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Government of Mauritius. (2022). The dangerous drugs (amendment) bill (no. XV of 2022) explanatory memorandum. Available online: https://mauritiusassembly.govmu.org/Documents/Bills/intro/2022/bill1522.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Government of Mauritius. (2023a). The HIV and AIDS (amendment) act 2023. Legal supplement of the government gazette of Mauritius, no.25 of 29 March 2023. Available online: https://health.govmu.org/health/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/The-HIV-And-AIDS-Amendment-Act-2023.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Government of Mauritius. (2023b). Drug user administrative panel. [Unpublished].

- Gray, R. M., Green, R., Bryant, J., Rance, J., & MacLean, S. (2017). How ‘Vulnerable’ young people describe their interactions with police: Building positive pathways to drug diversion and treatment in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia. Police Practice and Research, 20(1), 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, A., Selfridge, M., Watson, T. M., Macdonald, S., & Pauly, B. (2022). Young people who use drugs views toward the power and authority of police officers. Contemporary Drug Problems, 49(2), 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harm Reduction International. (2013). Injecting drug use among under-18s a snapshot of available data. Available online: https://www.hri.global/files/2014/08/06/injecting_among_under_18s_snapshot_WEB.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Harm Reduction International. (2024a). The global state of harm reduction 2024. Available online: https://hri.global/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/HRI-GSHR-24_full-document_1411.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Harm Reduction International. (2024b). A world of harm how U.S. taxpayers fund the global war on drugs over evidence-based health responses. Available online: https://hri.global/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/A-World-of-Harm-Report-FINAL-11_25.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Hawk, M., Coulter, R. W. S., Egan, J. E., Fisk, S., Reuel Friedman, M., Tula, M., & Kinsky, S. (2017). Harm reduction principles for healthcare settings. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(1), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Herz, A., Peters, L., & Truschkat, I. (2015). How to do qualitative structural analysis? The qualitative interpretation of network maps and narrative interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(1), 9. Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs150190 (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Hines, L., & Trickey, A. (2020). Global data on young people who inject drugs suggests harm reduction approaches should be scaled up. Bristol Policy Briefing 85: June 2020. Available online: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/policybristol/briefings-and-reports-pdfs/2020-briefings-and-reports-pdfs/PolicyBriefing%2085%20HinesTrickeyGlobalDataInjectingDrugUse.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Hood, J. E., Banta-Green, C. J., Duchin, J. S., Breuner, J., Dell, W., Finegood, B., Glick, S. N., Hamblin, M., Holcomb, S., Mosse, D., Oliphant-Wells, T., & Shim, M.-H. M. (2020). Engaging an unstably housed population with low-barrier buprenorphine treatment at a syringe services program: Lessons learned from Seattle, Washington. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 41(3), 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press (US). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. (2023). Country factsheets Mauritius 2023 HIV and AIDS estimates: Adults and children living with HIV. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/mauritius (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. (2024). 2024 global AIDS report—The urgency of now: AIDS at a crossroads. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2024/global-aids-update-2024 (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Kiekens, A., Dierckx de Casterlé, B. D., Pellizzer, G., Mosha, I. H., Mosha, F., de Wit, T. F. R., Sangeda, R. Z., Surian, A., Vandaele, N., Vranken, L., Killewo, J., Jordan, M., & Vandamme, A.-M. (2021). Exploring the mechanisms behind HIV drug resistance in sub-Saharan Africa: Conceptual mapping of a complex adaptive system based on multi-disciplinary expert insights. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiekens, A., Mosha, I. H., Zlatić, L., Bwire, G. M., Mangara, A., Dierckx de Casterlé, B., Decouttere, C., Vandaele, N., Sangeda, R. Z., Swalehe, O., Cottone, P., Surian, A., Killewo, J., & Vandamme, A.-M. (2022). Factors associated with HIV drug resistance in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Analysis of a complex adaptive system. Pathogens, 10(12), 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiekens, A., & Vandamme, M. (2022). Qualitative systems mapping for complex public health problems: A practical guide. PLoS ONE, 17(2), e0264463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. W., Pulkki-Brannstrom, A. M., & Skordis-Worrall, J. (2014). Comparing the cost-effectiveness of harm reduction strategies: A case study of the Ukraine. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, A., & Pollard, R. (2013). IDPC/Youth RISE case study series: The impacts of drug policy on young people: Mauritius. Available online: https://idpc.net/publications/2014/04/idpc-youth-rise-case-study-series-the-impacts-of-drug-policy-on-young-people-mauritius (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Krug, A., Hildebrand, M., & Sun, N. (2015). “We don’t need services. We have no problems”: Exploring the experiences of young people who inject drugs in accessing harm reduction services. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18(2)(Suppl. S1), 19442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laurent, T. (2024). Toxicomanie: Nouveau protocole pour l’utilisation de la méthadone. Defimedia.info. Available online: https://defimedia.info/toxicomanie-nouveau-protocole-pour-lutilisation-de-la-methadone (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Le Mauricien. (2020). Développement Rassemblement Information et Prevention (DRIP): Renforcer les chances des enfants pour un avenir durable. Available online: https://www.lemauricien.com/actualites/societe/developpement-rassemblement-information-et-prevention-drip-renforcer-les-chances-des-enfants-pour-un-avenir-durable/389035/ (accessed on 23 August 2024).

- Leslie, E. M., Cherney, A., Smirnov, A., Kemp, R., & Najman, J. M. (2018). Experiences of police contact among young adult recreational drug users: A qualitative study. International Journal of Drug Policy, 56, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, D. T., Howard, L. C., Krueger, E. A., Fleischer, N. L., Hughes-Halbert, C., & Leventhal, A. M. (2022). Change in distress about police brutality and substance use among young people, 2017–2020. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 237, 109530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Merkinaite, S., Grund, J. P., & Frimpong, A. (2010). Young people and drugs: Next generation of harm reduction. International Journal of Drug Policy, 21(2), 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health & Wellness. (2020a). People who inject drugs integrated biological and behavioural survey 2020. Available online: https://health.govmu.org/Documents/Legislations/Documents/PWID_FINAL_REPORT%20%281%29.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Ministry of Health & Wellness. (2020b). Statistics on HIV/AIDS (as at end of December 2020). Available online: https://health.govmu.org/health/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/HIV-2020.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Ministry of Health & Wellness. (2021). Mauritius non-communicable diseases survey 2021. Available online: https://files.aho.afro.who.int/afahobckpcontainer/production/files/Mauritius-Non-Communicable-Diseases-Survey-2021.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Ministry of Health & Wellness. (2023a). Republic of Mauritius national HIV action plan 2023–2027. Available online: https://health.govmu.org/health/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/NAP-Final-2023-2027.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Ministry of Health & Wellness. (2023b). Protocoles de prise en charge de l’usage de drogues à Maurice. Unpublished.

- Ministry of Health & Wellness. (2024a). Statistics on HIV/AIDS (as at end of June 2023). Available online: https://health.govmu.org/health/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/HIV-Report-as-at-June-2023.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Ministry of Health & Wellness. (2024b). HIV/AIDS and harm reduction unit. Available online: https://health.govmu.org/health/?page_id=5495 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Moorthi, G. (2014). Models, experts, and mutants: Exploring the relationships between peer educators and injecting drug user clients in Delhi’s harm reduction programs. Qualitative Social Work, 13(1), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassau, T., Kolla, G., Mason, K., Hopkins, S., Tookey, P., McLean, E., Werb, D., & Scheim, A. (2022). Service utilization patterns and characteristics among clients of integrated supervised consumption sites in Toronto, Canada. Harm Reduction Journal, 19(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Agency for the Treatment & Rehabilitation of Substance Abusers. (2010). Patterns & trends of alcohol and other drug use series. Vol. 6. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20220708062314/http://natresa.govmu.org/English/Documents/NATRESA_Year_2010_PTAODU_FINAL_REPORT.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- National Drug Secretariat, Prime Minister’s Office. (2020). National drug observatory of the republic of Mauritius 2020. Available online: https://mroiti.govmu.org/Communique/NDO%20Report%202020%20-%20Final.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- National Drug Secretariat, Prime Minister’s Office. (2022). National drug observatory of the republic of Mauritius 2022. Available online: https://mroiti.govmu.org/Communique/National%20Drug%20Observatory%20Report%202022.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Nuggehalli Srinivas, N. (2015). Capacity building and performance in local health systems—A realist evaluation of a local health system strengthening intervention in Tumukur, India [Doctoral thesis, Université Catholique de Louvain]. Available online: https://dial.uclouvain.be/pr/boreal/object/boreal:159372 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Owoeye, O., Daniels, C., Rostom, G., & Alando, C. (2023). Mauritius HIV response transition plan. [Unpublished].

- Prevention Information et Lutte Contre le Sida. (2017). The people living with HIV stigma index. Available online: http://web.archive.org/web/20200901012935/http://pils.mu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/STIGMA_F.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Prime Minister’s Office. (2019). National drug control master plan (2019–2023). Available online: https://mroiti.govmu.org/Communique/National%20Drug%20Control%20Master%20Plan.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Prime Minister’s Office. (2022). Consultant Moreea discusses progress of Hepatitis C treatment with Prime Minister. Available online: https://govmu.org/EN/newsgov/SitePages/Consultant-Moreea-discusses-progress-of-Hepatitis-C-treatment-with-Prime-Minister.aspx?_gl=1*wyc495*_ga*NDE5MzcwODc2LjE3MzgxMzM4MzE.*_ga_JFCCER4YDE*MTczODEzMzgzMS4xLjEuMTczODEzNTk0My42MC4wLjA (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Puzhko, S., Eisenberg, M. J., Filion, K. B., Windle, S. B., Hébert-Losier, A., Gore, G., Paraskevopoulos, E., Martel, M. O., & Kudrina, I. (2022). Effectiveness of interventions for prevention of common infections among opioid users: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 749033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pype, P., Mertens, F., Helewaut, F., & Krystallidou, D. (2018). Healthcare teams as complex adaptive systems: Understanding team behaviour through team members’ perception of interpersonal interaction. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsewak, S., Putteeraj, M., & Somanah, J. (2020). Exploring substance use disorders and relapse in Mauritian male addicts. Heliyon, 6(8), e04731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, E. A., Kaduri, P., Masao, F., Mbwambo, J. K., & McCurdy, S. A. (2016). Harm reduction as a complex adaptive system: A dynamic framework for analyzing Tanzanian policies concerning heroin use. International Journal of Drug Policy, 30, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnapalan, S., & Lang, D. (2020). Health care organizations as complex adaptive systems. Health Care Management, 39(1), 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rêgo, X., Oliveira, M. J., Lameira, C., & Cruz, O. S. (2021). 20 years of Portuguese drug policy: Developments, challenges, and the quest for human rights. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satinsky, E. N., Kleinman, M. B., Tralka, H. M., Jack, H. E., Myers, B., & Magidson, J. F. (2021). Peer-delivered services for substance use in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. International Journal of Drug Policy, 95, 103252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, A., Sibeko, G., Shelly, S., Rossouw, T., Zishiri, V., & Venter, W. (2020). Southern African HIV clinicians society guidelines for harm reduction. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine, 21(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Mauritius. (2021). Economic and social indicators: Crime, justice and security statistics. Available online: https://statsmauritius.govmu.org/Pages/Statistics/By_Subject/CJS/SB_CJS.aspx (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Statistics Mauritius. (2022). Crime, justice and security statistics 2020–2022. Available online: https://statsmauritius.govmu.org/Pages/Statistics/By_Subject/CJS/SB_CJS.aspx (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- St Cyr, J.-M. (2024). Rajeunissement de la toxicomanie—La méthadone à 15 ans: Une solution controversée. Defimedia.info. Available online: https://defimedia.info/rajeunissement-de-la-toxicomanie-la-methadone-15-ans-une-solution-controversee (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Stengel, C. M., Mane, F., Guise, A., Pouye, M., Sigrist, M., & Rhodes, T. (2018). “They accept me, because I was one of them”: Formative qualitative research supporting the feasibility of peer-led outreach for people who use drugs in Dakar, Senegal. Harm Reduction Journal, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockings, E., Hall, W. D., Lynskey, M., Morley, K. I., Reavley, N., Strang, J., Patton, G., & Degenhardt, L. (2016). Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3), 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowe, M. J., Feher, O., Vas, B., Kayastha, S., & Greer, A. (2022). The challenges, opportunities, and strategies of engaging young people who use drugs in harm reduction: Insights from young people with lived and living experience. Harm Reduction Journal, 19, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2023). Advisory: Low barrier models of care for substance use disorders. Available online: https://library.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/advisory-low-barrier-models-of-care-pep23-02-00-005.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- The Global Commission on Drug Policy. (2011). War on drugs. Available online: https://www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/reports/the-war-on-drugs (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- The Health Foundation. (2010). Evidence scan: Complex adaptive systems. Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/complex-adaptive-systems (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Thomas, F. (2022). Enquête exclusive: Ramener de la méthadone chez soi: Non autorisé mais possible. Defimedia.info. Available online: https://defimedia.info/enquete-exclusive-ramener-de-la-methadone-chez-soi-non-autorise-mais-possible (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Thomas, F. (2023a). Méthadone à Maurice: Entre traitement et trafic. Defimedia.info. Available online: https://defimedia.info/methadone-maurice-entre-traitement-et-trafic (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Thomas, F. (2023b). Traitement des usagers de drogues: Tout savoir sur le drug users administrative panel. Defimedia.info. Available online: https://defimedia.info/traitement-des-usagers-de-drogue-tout-savoir-sur-le-drug-users-administrative-panel (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Thomas, F. (2024). Centres de désintoxication clandestins entre séquestration et passage à tabac. Defimedia.info. Available online: https://defimedia.info/centres-de-desintoxication-clandestins-entre-sequestration-et-passage-tabac (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Thornberg, R., & Charmaz, K. (2014). Grounded theory and theoretical coding. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 153–169). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (2019). Committee on economic, social and cultural rights on economic, social and cultural rights concluding observations on the fifth periodic report of Mauritius. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3864986?v=pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2016). A practical guide for civil society HIV service providers among people who use drugs: Improving cooperation and interaction with law enforcement officials. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/hiv-aids/2016/Practical_Guide_for_Civil_Society_HIV_Service_Providers.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2017). World drug report 2017. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2017/index.html (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2023). Regional estimates of people who inject drugs, living with HIV, HCV and HBV 2022. Available online: https://dataunodc.un.org/dp-drug-use-characteristics-regional (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2024). World drug report 2024 key findings and conclusions. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2023.html (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- White, G., Luczak, S. E., Mundia, B., & Goorah, S. (2020). Exploring the perceived risks and benefits of heroin use among young people (18–24 years) in Mauritius: Economic insights from an exploratory qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Global survey 2022: Prevalence of HCV in the general population. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/hepatitis---prevalence-of-chronic-hepatitis-among-the-general-population (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Yoon, G. H., Levengood, T. W., Davoust, M. J., Ogden, S. N., Kral, A. H., Cahill, S. R., & Bazzi, A. R. (2022). Implementation and sustainability of safe consumption sites: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Harm Reduction Journal, 19, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Young Heroin Users (18–24 Years) | Service Providers (Including Informal Providers) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number per group | 22 | 5 |

| Characteristics | ||

| Currently using heroin (inject/smoke) | 19 | 1 |

| Enrolled on methadone but injected in the past 2 months | 1 | |

| On codeine phosphate but injected occasionally | 1 | |

| Were drug-free at the time of the interview | 1 (injected in the past 4 months) | 2 |

| Combined heroin with other substances | 7 | 2 |

| Were HIV-positive (disclosed during the interview) | 2 | 1 |

| Were HepC-positive | Undisclosed | Undisclosed |

| Type of Service User | Combinations |

|---|---|

| Single Service Users |

|

| Dual Service Users |

|

| Triple Service Users |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

White, G.; Luczak, S.E.; Nöstlinger, C. Harm Reduction as a Complex Adaptive System: Results from a Qualitative Structural Analysis of Services Accessed by Young Heroin Users in Mauritius. Youth 2025, 5, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010010

White G, Luczak SE, Nöstlinger C. Harm Reduction as a Complex Adaptive System: Results from a Qualitative Structural Analysis of Services Accessed by Young Heroin Users in Mauritius. Youth. 2025; 5(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhite, Gareth, Susan E. Luczak, and Christiana Nöstlinger. 2025. "Harm Reduction as a Complex Adaptive System: Results from a Qualitative Structural Analysis of Services Accessed by Young Heroin Users in Mauritius" Youth 5, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010010

APA StyleWhite, G., Luczak, S. E., & Nöstlinger, C. (2025). Harm Reduction as a Complex Adaptive System: Results from a Qualitative Structural Analysis of Services Accessed by Young Heroin Users in Mauritius. Youth, 5(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/youth5010010